Abstract

We investigated the antimicrobial susceptibility of 50 environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139 collected in surface waters in Haiti in July 2012, during an active cholera outbreak. A panel of 16 antibiotics was tested on the isolates using the disk diffusion method and PCR detection of seven resistance-associated genes (strA/B, sul1/2, ermA/B, and mefA). All isolates were susceptible to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefotaxime, imipenem, ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, amikacin, and gentamicin. Nearly a quarter (22.0%) of the isolates were susceptible to all 16 antimicrobials tested and only 8.0% of the isolates (n = 4) were multidrug-resistant. The highest proportions of resistant isolates were observed for sulfonamide (70.0%), amoxicillin (12.0%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (10.0%). One strain was resistant to erythromycin and one to doxycycline, two antibiotics used to treat cholera in Haiti. Among the 50 isolates, 78% possessed at least two resistance-associated genes, and the genes sul1, ermA, and strB were detected in all four multidrug-resistant isolates. Our results clearly indicate that the autochthonous population of V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 found in surface waters in Haiti shows antimicrobial patterns different from that of the outbreak strain. The presence in the Haitian aquatic environment of V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 with reduced susceptibility or resistance to antibiotics used in human medicine may constitute a mild public health threat.

Keywords: Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139, antimicrobial resistance, Haiti, aquatic environment, cholera

Introduction

Reports on clinical strains of Vibrio cholerae O1 resistant to commonly used antibiotics are on the rise (Garg et al., 2000, 2001; Ghosh and Ramamurthy, 2011; Harris et al., 2012). Antibiotic resistance is a global health concern because resulting infections can be more difficult to treat. The increase in resistance to antimicrobial drugs can result either from the accumulation of genetic mutations, following exposure of the circulating bacteria to antibiotics during the medical treatment of epidemics, or from the acquisition of resistance genes, through the mobilization and exchange of a variety of genetic elements. In the case of V. cholerae, self-transmissible mobile genetic elements may harbor an SXT constin (a large conjugative element), which may confer resistance to sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, chloramphenicol, and streptomycin (Hochhut et al., 2001).

Surprisingly, data on the susceptibility of environmental isolates of V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 are still scarce (Kumar et al., 2009; Bier et al., 2015; Bhuyan et al., 2016). However, knowledge on the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in these serogroups is of global health interest for two reasons.

First, contrary to O1/O139, non-O1/non-O139 serogroups are detected worldwide in all types of waters: freshwater, estuarine, saline water, and wastewater. Aquatic environments may provide an ideal setting for the acquisition and dissemination of antibiotic resistance: (i) they are frequently affected by anthropogenic activities (Marti et al., 2014); (ii) they contain autochthonous bacterial flora that may harbor resistance-associated genes; (iii) they bring bacteria from different origins (human, livestock, etc.) into contact with each other; (iv) they can contain antimicrobials or biocides which may select for resistant bacteria. Wastewater constitutes a hot spot for the emergence of antimicrobial resistance (Rizzo et al., 2013), particularly for V. cholerae, which has a dual life cycle (intestinal and aquatic); (Schoolnik and Yildiz, 2000). Therefore, due to its specific genetic abilities, and its ecological characteristics, V. cholerae may be an important vehicle of transmission of resistance genes in all aquatic environments either within bacterial species or between bacterial genera. In countries with endemic cholera, these autochthonous aquatic serogroups of V. cholerae can also co-infect cholera cases, providing an opportunity for the exchange of antimicrobial resistance genes with clinical strains of serogroup O1 in the human intestinal lumen. Furthermore, the intestinal epidemic clones circulating in the environment can theoretically exchange resistance genes with the autochthonous populations of V. cholerae.

Second, some clones of V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 from aquatic environments may be opportunist pathogens, which can cause gastro-intestinal or extra-intestinal infections (bacteremia, septicemic, otitis, etc.) (Lukinmaa et al., 2006; Deshayes et al., 2015). Throughout the world, the number of cases of V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 infections are rising (Baker-Austin et al., 2013); moreover, reports of very severe infections are becoming more frequent, with even one death recently reported in Austria (Hirk et al., 2016). In Haiti, V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 has been shown to be a local intestinal infectious pathogen. Very early in the on-going Haitian cholera outbreak (November 2010), a microbiological investigation of 81 clinical cases of acute diarrhea with varying severity from 18 towns showed that V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 was isolated from 28% of the stool specimens, either alone (n = 17) or in co-culture with toxigenic V. cholerae O1 (n = 5). The latter cases were confirmed cholera cases, as were 39 other cases with the presence of toxigenic V. cholerae O1 alone (Hasan et al., 2012). However two years later (from April 2012 to March 2013), systematic testing of profuse watery diarrhea cases was carried out in four hospitals that had cholera treatment facilities. Among the 1616 specimens of stools tested in culture, 60% were positive for toxigenic V. cholerae O1, one gave a non-toxigenic isolate of V. cholerae O1, but none were positive for V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 (Steenland et al., 2013). Other studies on stools collected from patients during the Haiti outbreak found only serogroup O1 isolates (Talkington et al., 2011; Katz et al., 2013). These results are not contradictory: non-O1/non-O139 serogroups can cause a diarrheal disease that is generally less severe than cholera and do not particularly have epidemic potential (Menon et al., 2009). Nevertheless, the pathogenic clones of V. cholerae, whether they are agents of cholera or of milder infections, can circulate via aquatic environments and some authors even speculate that toxigenic clones of V. cholerae are autochthonous to estuaries and rivers systems worldwide as are other clones (Colwell, 1996).

We therefore investigated the antimicrobial susceptibility of 50 environmental isolates of non-toxigenic V. cholerae collected in various surface waters in Haiti in July 2012, during the active cholera epidemic (Baron et al., 2013). The aim of this study was to document, in this context, the susceptibility of strains belonging to non-O1/non-O139 serogroups to 16 antibiotics used and compare it to those of the Haitian epidemic strain.

Materials and methods

Collection of strains

In a previous study, water samples, including wastewater, were collected from 35 stations described in Baron et al. (2013). V. cholerae was detected by culturing samples on TCBS (thiosulfate citrate bile sucrose) agar (Difco, BD Biosciences, Le pont de Claix, France) after enrichment in peptone alkaline saline water (41°C ± 1 for 16–24 h; Muic, 1990). Presumptive identification of V. cholerae was given to all sucrose-fermenting isolates that were able to grow on nutrient agar without added NaCl, and that tested positive for oxidase (Baron et al., 2007). Presumptive V. cholerae were isolated from 27 of the 35 stations sampled, but isolates from six stations could not be regrown (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of the 50 isolates of confirmed V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 and characteristics of the 27 stations (see Baron et al., 2013 for correspondence).

| Sampling stations | Water characteristics | Number of isolates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department | Town | Location | IDa | Salinity (%0)b | Fecal contamination: | ||

| E. coli /100 mL | Groupd | ||||||

| West (Metropolitan area) | Port-au-Prince | Martissant (street wastewater) | 2 | NDc | ND | HFC | 2 |

| West (Metropolitan area) | Carrefour | Mariani (wastewater in the river) | 32 | 0.21 | 106,000 | HFC | NGe |

| West (Metropolitan area) | Carrefour | Mariani (river shore) | 33 | 0.20 | 35,000 | HFC | 2 |

| West (Metropolitan area) | Carrefour | Mariani (river shore) | 34 | 0.21 | 46,000 | HFC | 3 |

| West (Metropolitan area) | Carrefour | Mariani (macrophyte lagoon) | 35 | 25.02 | 12,400 | HFC | NG |

| West (Metropolitan area) | Carrefour | Mariani (macrophyte lagoon) | 36 | 10.72 | 50,000 | HFC | NG |

| Artibonite | Gonaives | Small canal of wastewater | 19 | 2.09 | 91,000 | HFC | 4 |

| Artibonite | Gonaives | Large canal of wastewater | 24 | 1.40 | 36,000 | HFC | 3 |

| West | Thomazeau | Trou Caïman Lake | 3 | 1.27 | ND | LFC | 3 |

| West | Thomazeau | Etang Saumâtre Lake (shore) | 4 | 4.90 | ND | LFC | 3 |

| West | Thomazeau | Etang Saumâtre Lake (far from the shore) | 5 | 5.62 | ND | LFC | 2 |

| Artibonite | Saint Marc | Etang Bois-Neuf | 18 | 12.41 | 2000 | LFC | 5 |

| Artibonite | Saint Marc | Pont-Sondé (Artibonite River) | 6 | 0.14 | 4800 | LFC | 4 |

| Artibonite | Grande Saline | Main canal 1 | 17 | 0.15 | 2800 | LFC | 2 |

| Artibonite | Grande Saline | Main canal 2 | 16 | 0.15 | 3600 | LFC | 2 |

| Artibonite | Grande Saline | Drouin—main canal 3 (point-of-use) | 7 | 0.15 | 2100 | LFC | 2 |

| Artibonite | Grande Saline | Artibonite River estuary 1 | 9 | 0.14 | 2100 | LFC | 1 |

| Artibonite | Grande Saline | Artibonite River estuary 2 | 10 | 0.15 | 3100 | LFC | 1 |

| Artibonite | Grande Saline | Basin 1 | 14 | 0.75 | 1000 | LFC | 1 |

| Artibonite | Grande Saline | Basin 2 | 15 | 0.27 | < 100 | LFC | 4 |

| Artibonite | L'Estère | L'Estère (river) | 25 | 0.15 | 300 | LFC | 1 |

| Artibonite | L'Estère | L'Estère (small canal) | 26 | 0.15 | 400 | LFC | 1 |

| Artibonite | L'Estère | L'Estère (large canal) | 27 | 0.14 | 300 | LFC | 1 |

| Artibonite | L'Estère | L'Estère (roadside) | 28 | 0.37 | 4700 | LFC | NG |

| Artibonite | Desdunes | Route de Desdunes (small canal) | 29 | 0.26 | 200 | LFC | NG |

| Artibonite | Desdunes | Route de Desdunes (large canal) | 30 | 0.52 | 300 | LFC | 3 |

| Artibonite | Desdunes | Route de Desdunes (rice field) | 31 | 0.30 | < 100 | LFC | NG |

ID, identification number of the station;

salinity: fresh water < 0.5%¸; brackish water 0.5–16%¸;

ND, no data;

HFC, high fecal contamination: E. coli >104 CFU/100 mL; LFC, low fecal contamination: E. coli ≤ 104 CFU/100 mL;

NG, isolate from the National Health of Public Health in Haiti did not grow in the ANSES laboratory.

Fecal contamination (FC) was determined using Petrifilm™ Select Escherichia coli (Département Microbiologie Laboratoires 3M Santé, Cergy, France). Based on the FC level (Table 1), the 21 sampled stations were divided into two groups. The high FC (HFC) group for which the density of E. coli was at least 104 CFU/100 mL included five stations that were all wastewaters. The low FC (LFC) group, for which the E. coli density level was < 104 CFU/100 mL, included Trou Caïman Lake (Station 3) and Etang Saumâtre Lake (Stations 4 and 5; Table 1). Conductivity was assessed at the laboratory with a field conductometer (Hanna HI-99301, Grosseron, Nantes, France).

Confirmation and characterization of V. cholerae

Agglutination using a polyclonal antibody specific to the O1 surface antigen (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) was performed on presumptive V. cholerae isolates at the Haiti National Public Health Laboratory. A saline solution was used as a control to identify self-agglutinating isolates. One isolate per enrichment and per station was conserved and sent to the ANSES-Laboratory of Ploufragan-Plouzané for further analysis. The identification of presumptive V. cholerae was confirmed by PCR (Nandi et al., 2000). The genes coding for the O1 and O139 surface antigens (rfb) were assessed with PCR using O1- and O139-specific primers (Hoshino et al., 1998; Table 2). The cholera toxin gene ctxA was screened using PCR (Hoshino et al., 1998; Nandi et al., 2000).

Table 2.

List of primers used in this study.

| Targeted gene | Primer name | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | T°Ca | Amplicon size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ermA | ermA1 | TAACATCAGTACGGATATTG | 54 | 139 | Di Cesare et al., 2013 |

| ermA2 | AGTCTACACTTGGCTTAGG | ||||

| ermB | ermB1 | CCGAACACTAGGGTTGCTC | 54 | 200 | Di Cesare et al., 2013 |

| ermB2 | ATCTGGAACATCTGTGGTATG | ||||

| mef | mef1 | AGTATCATTAATCACTAGTGC | 54 | 348 | Di Cesare et al., 2013 |

| mef2 | TTCTTCTGGTACTAAAAGTGG | ||||

| sul1 | Sul1-1 | CGCACCGGAAACATCGCTGCAC | 65 | 162 | Pei et al., 2006 |

| Sul1-2 | TGAAGTTCCGCCGCAAGGCTCG | ||||

| sul2 | Sul2-1 | TCCGGTGGAGGCCGGTATCTGG | 57.5 | 190 | Pei et al., 2006 |

| Sul2-2 | CGGGAATGCCATCTGCCTTGAG | ||||

| O139 rfb | O139-1 | AGCCTCTTTATTACGGGTGG | 55 | 449 | Hoshino et al., 1998 |

| O139-2 | GTCAAACCCGATCGTAAAGG | ||||

| O1 rfb | O1-1 | GTTTCACTGAACAGATGGG | 55 | 192 | Hoshino et al., 1998 |

| O1-2 | GGTCATCTGTAAGTACAAC | ||||

| ctxA | ctx Ats | CTCAGACGGGATTTGTTAGGCACG | 64 | 301 | Nandi et al., 2000 |

| ctx A | TCTATCTCTGTAGCCCCTATTACG | ||||

| ompW | ompW ts | CACCAAGAAGGTGACTTTATTGTG | 64 | 588 | Nandi et al., 2000 |

| ompW ta | GAACTTATAACCACCCGCG | ||||

| strA | strA-F | GAGAGCGTGACCGCCTCATT | 57 | 862 | Popowska et al., 2012 |

| strA-R | TCTGCTTCATCTGGCGCTGC | ||||

| strB | strB-F | GCTCGGTCGTGAGAACAATC | 54 | 859 | Popowska et al., 2012 |

| strB-R | AGAATGCGTCCGCCATCTGT |

Annealing temperature.

Antibiotic resistance profiles

The susceptibility of V. cholerae isolates was tested using the disk diffusion method according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (CLSI, 2010a) for the 16 following antimicrobial agents: ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefotaxime, imipenem, chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, amikacin, gentamicin, streptomycin, tetracycline, doxycycline, sulfonamide, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and erythromycin (Table 3). E. coli ATCC 25922 served as a positive control. The CLSI interpretative criteria for disk diffusion susceptibility testing of Vibrio spp. (CLSI, 2010a) were used when available. For nalidixic acid, norfloxacin, amikacin, and streptomycin, the interpretative criteria for Enterobacteriaceae were used (CLSI, 2016; Table 3). No criteria were available for erythromycin or doxycycline; therefore, the distribution of the inhibition diameters was recorded and interpretation was based on obtained distribution plots. The separation between wild-type (microorganisms without acquired resistance mechanisms) and non-wild-type populations (microorganisms with acquired resistance mechanisms) was determined by visual inspection of the diameter distribution (Hombach et al., 2014). Wild-type populations were considered as susceptible populations and non-wild-type as resistant populations. The few intermediate results were categorized as resistant for this study.

Table 3.

Interpretative criteria used to determine antimicrobial susceptibility with the disk diffusion test in Vibrio cholerae isolates.

| Antimicrobial class | Antimicrobial agent | Abbreviation | Disk content (μg) | Zone diameter interpretative criteria (mm) | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | |||||

| ß-lactams | Ampicillin | AM | 10 | ≥17 | 14–16 | ≤ 13 | CLSI, 2010a |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | AMC | 20/10 | ≥18 | 14–17 | ≤ 13 | CLSI, 2010a | |

| Cefotaxime | CTX | 30 | ≥26 | 23–25 | ≤ 22 | CLSI, 2010a | |

| Imipenem | IPM | 10 | ≥23 | 20–22 | ≤ 19 | CLSI, 2010a | |

| Phenicols | Chloramphenicol | C | 30 | ≥18 | 13–17 | ≤ 12 | CLSI, 2010a |

| Aminoglycosides | Amikacin | AMK | 30 | ≥17 | 15–16 | ≤ 14 | CLSI, 2010a |

| Gentamicin | GEN | 10 | ≥15 | 13–14 | ≤ 12 | CLSI, 2010a | |

| Streptomycin | STR | 10 | ≥17 | 13–16 | ≤ 12 | CLSI, 2016 | |

| Quinolones | Ciprofloxacin | CIP | 5 | ≥21 | 16–20 | ≤ 15 | CLSI, 2010a |

| Nalidixic acid | NA | 30 | ≥19 | 14–18 | ≤ 13 | CLSI, 2016 | |

| Norfloxacin | NOR | 10 | ≥17 | 13–16 | ≤ 12 | CLSI, 2016 | |

| Folate pathway inhibitors | Sulfonamide | SSS | 300 | ≥17 | 13–16 | ≤ 12 | CLSI, 2010a |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | SXT | 1.25/23.75 | ≥16 | 11–15 | ≤ 10 | CLSI, 2010a | |

| Tetracyclines | Tetracycline | TET | 30 | ≥15 | 12–14 | ≤ 11 | CLSI, 2010a |

| Doxycycline | DO | 30 | – | – | – | ||

| Macrolides | Erythromycin | ERY | 15 | ≥17 | 13–16 | ≤ 12 | CLSI, 2016 |

Interpretative criteria specific for Vibrio spp., including V. cholerae described in CLSI document M45 3rd edition (CLSI, 2010a) are adapted from those for Enterobacteriaceae M100 25S (CLSI, 2010b). For streptomycin, norfloxacin and nalidixic acid breakpoints described for Enterobacteriaceae in M100 26S (CLSI, 2016) were used. No breakpoints were available for doxycycline or for erythromycin.

Genes associated with resistance to streptomycin (strA and strB) and to sulfonamide (sul1 and sul2)-which may be associated with the presence of V. cholerae SXT-as well as genes associated with erythromycin resistance (ermA, ermB, and mefA)-an antimicrobial agent used in Haiti for cholera treatment-were detected using PCR (Pei et al., 2006; Popowska et al., 2012; Di Cesare et al., 2013). Class 1, 2, and 3 integrons were screened using PCR (Barraud et al., 2010). All primer pairs, target genes, corresponding annealing temperatures, and amplicon sizes are listed in Table 2.

Results

Collection of isolates

The collection was composed of 50 isolates of V. cholerae from 21 stations (Table 1): 36 (72.0%) were isolated from the 16 LFC stations and 14 from the 5 HFC stations (for description of stations see Baron et al., 2013). None of the 50 V. cholerae isolates belonged to O1 or O139 serogroups nor produced the cholera toxin (i.e., the ctxA gene was not detected).

Antibiotic resistance phenotypes

All tested isolates were susceptible to seven antibiotics of the tested panel: amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefotaxime, imipenem, ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, amikacin, and gentamicin. Eleven isolates (22.0%) were susceptible to all 16 tested antibiotics (three isolates out of 14 from the HFC group and eight out of 36 from the LFC group). The highest proportions of resistant isolates were observed for sulfonamide (70.0%), ampicillin (12.0%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (10.0%; Table 4).

Table 4.

Phenotypic and genotypic profiles of susceptibility in the 50 strains of V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139.

| Phenotypic antimicrobial suceptibilityc | Molecular determinantsd | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Station | Groupa | Resistance profile | SSS | STR | Eb | DOb | TET | AM | NA | SXT | C | sul1 | sul2 | strA | strB | ermA | ermB | mefA | Integron |

| VCH3 | 2 | HFC | C−SXT−AM−TET−SSS−STR−E | R | R | 7* | 24 | R | R | S | R | R | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| VCH126 | 19 | HFC | C−SXT−TET−SSS−STR−DO | R | R | 22 | 15* | R | S | S | R | R | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| VCH85 | 25 | LFC | C−SXT−SSS−STR | R | R | 18 | 25 | S | S | S | R | R | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| VCH55 | 17 | LFC | AM−SSS−STR | R | R | 21 | 29 | S | R | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| VCH23 | 6 | LFC | AM−SSS | R | S | 22 | 29 | S | R | S | S | S | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| VCH28 | 7 | LFC | AM−SSS | R | S | 16 | 27 | S | R | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH59 | 18 | LFC | AN−SSS | R | S | 22 | 31 | S | S | R | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH12 | 3 | LFC | SSS−STR | R | R | 18 | 27 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH113 | 33 | HFC | SXT−SSS | R | S | 18 | 27 | S | S | S | R | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH13 | 5 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 18 | 29 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| VCH66 | 18 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 21 | 26 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH72 | 19 | HFC | SSS | R | S | 20 | 27 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| VCH4 | 4 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 20 | 27 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH31 | 9 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 19 | 28 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH107 | 30 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 18 | 27 | S | S | S | S | S | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| VCH5 | 4 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 17 | 29 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| VCH30 | 7 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 23 | 28 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| VCH41 | 15 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 21 | 28 | S | S | S | S | S | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH45 | 15 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 18 | 29 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH52 | 16 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 21 | 31 | S | S | S | S | S | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH57 | 17 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 22 | 28 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| VCH65 | 18 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 21 | 28 | S | S | S | S | S | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH76 | 24 | HFC | SSS | R | S | 20 | 29 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH79 | 24 | HFC | SSS | R | S | 20 | 29 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH81 | 24 | HFC | SSS | R | S | 23 | 29 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH90 | 27 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 17 | 29 | S | S | S | S | S | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − |

| VCH104 | 30 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 21 | 29 | S | S | S | S | S | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| VCH2 | 2 | HFC | SSS | R | S | 18 | 28 | S | S | S | S | S | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| VCH9 | 3 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 22 | 29 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH102 | 30 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 19 | 32 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH112 | 33 | HFC | SSS | R | S | 21 | 29 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH48 | 15 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 23 | 30 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH50 | 16 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 22 | 31 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH117 | 34 | HFC | SSS | R | S | 21 | 30 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH146 | 4 | LFC | SSS | R | S | 23 | 30 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH17 | 5 | LFC | AM | S | S | 24 | 30 | S | R | S | S | S | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| VCH26 | 6 | LFC | AM | S | S | 21 | 31 | S | R | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH69 | 19 | HFC | AN | S | S | 22 | 29 | S | S | R | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH61 | 18 | LFC | SXT | S | S | 23 | 26 | S | S | S | R | S | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH22 | 6 | LFC | S | S | S | 20 | 32 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| VCH7 | 3 | LFC | S | S | S | 20 | 30 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH34−1 | 10 | LFC | S | S | S | 19 | 32 | S | S | S | S | S | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| VCH40 | 14 | LFC | S | S | S | 19 | 30 | S | S | S | S | S | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH44 | 15 | LFC | S | S | S | 20 | 30 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH116 | 34 | HFC | S | S | S | 20 | 30 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH62 | 18 | LFC | S | S | S | 22 | 32 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH70 | 19 | HFC | S | S | S | 21 | 34 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH89 | 26 | LFC | S | S | S | 14 | 30 | S | S | S | S | S | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| VCH131 | 34 | HFC | S | S | S | 21 | 32 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| VCH20 | 6 | LFC | S | S | S | 17 | 31 | S | S | S | S | S | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

SSS, sulfonamide; STR, streptomycin; E, erythromycin; DO, doxycycline; TET, tetracycline; AM, ampicillin; NA, nalidixic acid; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and C, chloramphenicol; R, resistant; S, susceptible; all intermediate results were considered as resistant.

Based on the fecal contamination level, the 21 sampled sites were divided into two groups. High fecal contamination (HFC) with E. coli >104 CFU/100 mL; low fecal contamination (LFC) with E. coli ≤ 104 CFU/100 mL.

For doxycycline and erythromycin, as no interpretative criteria was available, the diameter of inhibition is given.* indicates that the isolate was resistant to this antimicrobial agent.

All the isolates were susceptible to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, amikacin, gentamicin, cefotaxime, ciprofloxacin, imipenem and norfloxacin, and were not included in this table.

+, gene/integron was detected by PCR; -, gene/integron was not detected by PCR.

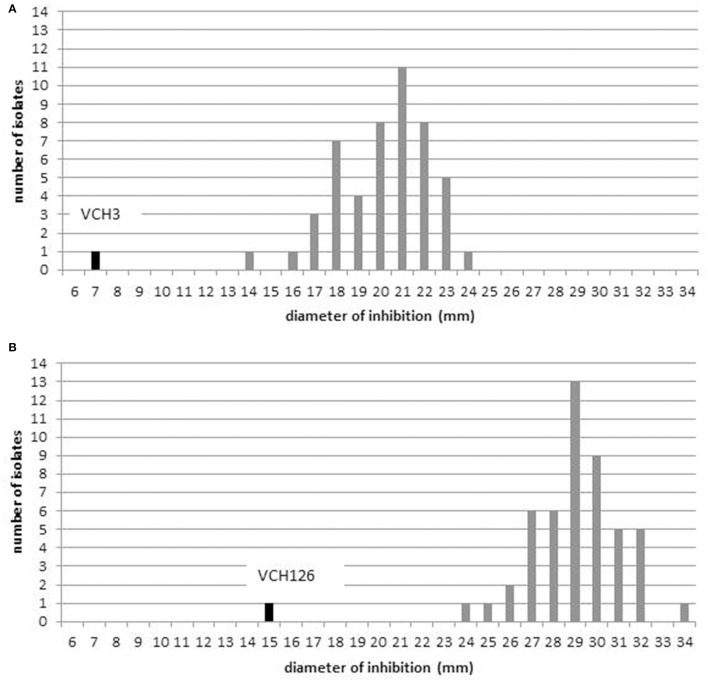

One isolate, VCH126 from HFC station 19, showed a smaller inhibition zone (15 mm) for doxycycline than the 49 other isolates (Figure 1B) and was resistant to tetracycline. Given that the results from the tetracycline disk are typically used to predict susceptibility to doxycycline (Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 1999), we concluded that VCH126 was resistant to doxycycline. VCH3, isolated from LFC station 2, showed an inhibition zone of 7 mm for erythromycin (Figure 1A); this isolate was declared resistant to erythromycin.

Figure 1.

Distribution of diffusion zone diameters: (A) erythromycin (15 μg); (B) doxycycline (30 μg).

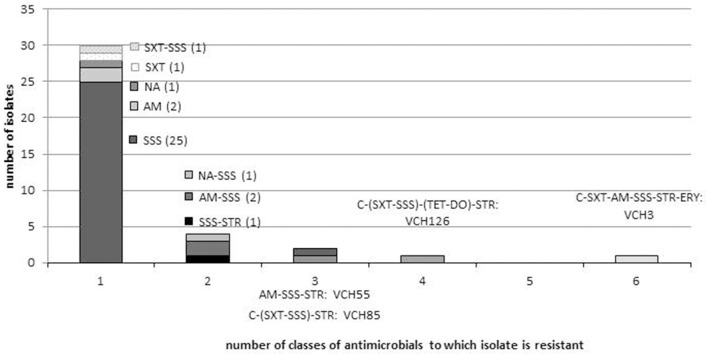

Among the 39 isolates that were resistant to at least one antibiotic, 12 different profiles were observed. The dominant profile was resistance to sulfonamide only (n = 26/39; 66.7%), and the 11 other profiles were represented by only one or two isolates (Figure 2). Antimicrobial resistance was not significantly different between LFC and HFC stations (Fisher exact test; p = 0.91).

Figure 2.

Distribution of resistance profiles in V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 isolates. The number of isolates for each resistance profile is indicated in brackets, and isolate identity is indicated only for the four multidrug-resistant strains. AM, Ampicillin; C, chloramphenicol; NA, nalidixic acid; STR, streptomycin; TET, tetracycline; DO, doxycycline; SSS, sulfonamide; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; ERY, erythromycin. SXT and SSS belong to the class of folate inhibitor pathway and DO and TET to the tetracycline class.

Multidrug resistant isolates are defined as isolates which are resistant to at least three different antimicrobial classes (Magiorakos et al., 2012). Four isolates (10.5%), VCH3, VCH126, VCH85, and VCH55, were multidrug-resistant (Table 4). They displayed four different profiles (Figure 2). The four isolates were all resistant to streptomycin and sulfonamide, but none were resistant to nalidixic acid. Two isolates (VCH3 and VCH126), from stations 2 and 19, were resistant respectively to six and four classes of antimicrobials. They were both resistant to the antimicrobials belonging to the classes of folate pathway inhibitors (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, sulfonamide), phenicols, tetracycline, and aminoglycosides. These phenotypic resistances may be conferred by genes that are frequently associated with the presence of an SXT element. Nevertheless, the class 1 integron integrase gene was detected in one isolate (VCH3) only. VCH3 was also resistant to erythromycin and ampicillin, but susceptible to doxycycline. VCH126 was also resistant to doxycycline.

Antibiotic resistance genotypes

Seven resistance-associated genes were screened on the 50 isolates, regardless of the resistance profile. We chose to screen for resistance associated with streptomycin (strA/B) and sulfonamide (sul1/2), because these genes can be present in the SXT constin, and with erythromycin (ermA/B, mefA) which is used in Haiti for cholera treatment.

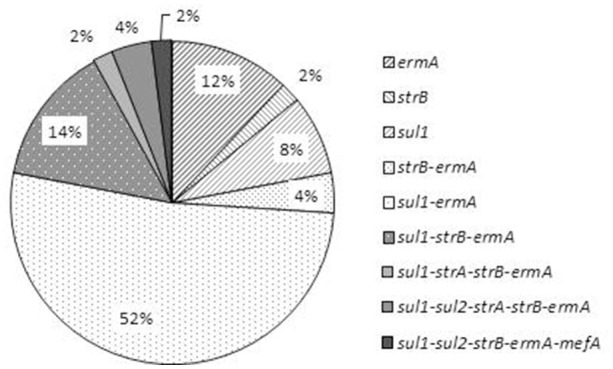

Among the 50 isolates, 78% possessed at least two resistance-associated genes (Figure 3). The genes sul1, ermA, and strB were detected in the four multidrug-resistant isolates. Three of these isolates harbored five resistance-associated genes and one harbored four genes (Figure 3). The sul1 gene was detected in 41 (82%) isolates. The sul2 gene was detected only in three isolates (6.0%) and always in association with sul1; these isolates were resistant to sulfonamide. The strA gene was detected only in three isolates (6.0%) and always in association with strB; these three isolates were resistant to streptomycin. In contrast, the two other isolates that were resistant to streptomycin did not harbor either strA or strB. StrB gene was detected in 11 other isolates that were susceptible to streptomycin. ErmA gene was detected in 90.0% of the isolates, while only one strain (VCH3) was resistant to erythromycin; this strain harbored only ermA. Mef A was detected in only one strain (VCH90) which also carried the ermA gene, but was susceptible to erythromycin (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Distribution of the profiles of resistance-associated genes in the 50 V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 isolates.

Discussion

Only few studies have investigated the presence of resistance-associated genes in V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 strains in association with phenotypic susceptibility (Raissy et al., 2012; Bier et al., 2015; Bhuyan et al., 2016). One study was carried out on 184 V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 strains of clinical and environmental origin (water and fish), and showed that 11 were resistant to ampicillin, but all were sensitive to the other beta-lactam antibiotics tested, with the exception of four strains resistant to carbapenems (Bier et al., 2015). However, no beta-lactamase-coding genes were found. The other study screened for three resistance-associated genes (ermB, strA, and sul2) on three strains of V. cholerae isolated from seafood in Iran. Only the strA gene was detected in one isolate which was resistant to streptomycin, amikacin, and gentamicin (Raissy et al., 2012).

In this study, we detected strA in three isolates which were resistant to streptomycin but susceptible to the other aminoglycosides tested. The ermA gene was not detected, but the ermB gene was detected in 90% of V. cholerae isolates, although only one isolate showed a resistance phenotype. This gene, which codes for the methylation of the target, is frequently detected in Staphylococcus spp. On the contrary, one strain possessed both the ermA gene and the mefA gene, which codes for an efflux pump, another mechanism of resistance. Nonetheless, this isolate presented a susceptible phenotype (zone of inhibition = 17 mm).

Our study indicates that the PCR and susceptibility testing approaches are complementary, because they show the presence of genes associated with resistance in susceptible strains and also their absence in resistant strains. This indicates that the link between genes and phenotypes is probably complex. Interestingly, the multidrug-resistant isolates were those that harbored the highest number of resistance-associated genes. Even if a larger panel of associated resistance genes could be investigated, it would not be exhaustive.

Screening for resistance genes is just a first step: it provides information on the reservoir of resistance genes in the autochthonous aquatic V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 population in our collection of isolates. The next step requires the localization of these genes (chromosome, plasmid, ICE) to estimate their potential for dissemination more precisely. Some of these resistance-associated genes are associated with mobile genetic elements. The sul1/2 genes have been detected in class 1 integrons or/and in plasmids in V. cholerae O1 (Dalsgaard et al., 2001; Iwanaga et al., 2004; Ceccarelli et al., 2006) and in non-O1/non-O139 serogroups (Dalsgaard et al., 2000). The strA/B genes are associated with the class 1 integron as well as the SXT element (Hochhut et al., 2001; Iwanaga et al., 2004) in V. cholerae O1. In this study, a class 1 integron was detected in only one strain (VCH3), which showed the expected multidrug resistance (chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ampicillin, tetracycline, and sulfonamide) that can be harbored by the SXT/R391 integrative and conjugative element (ICE). In Haiti, Ceccarelli et al. (2013) described the presence of two types of SXT/R391 ICEs displaying different genetic organizations, one in O1 serogroup strains (ICEVchHai1) and another (ICEVchHai2) in some clinical isolates of non-O1/non-O139 serogroups (Ceccarelli et al., 2013). ICEVchHai2 lacks the antibiotic resistance cluster typically inserted in variable region 3. It remains to be seen whether VCH3 harbors an ICE and, if so, which genetic organization it possesses.

Considering the Haitian situation, we compared the susceptibility profiles of the non-O1/non-O139 isolates with those of V. cholerae O1 of either clinical or environmental origin, which have been published since the beginning of the cholera outbreak in October 2010 (Sjölund-Karlsson et al., 2011; Talkington et al., 2011; Alam et al., 2014, 2015; Folster et al., 2014). Our results clearly indicate that the non-O1/non-O139 V. cholerae isolated from surface waters showed phenotypical antimicrobial patterns different from those of the epidemic strain.

Two collections of toxigenic V. cholerae O1 strains have been tested for antimicrobial susceptibility: 122 laboratory-confirmed V. cholerae O1 clinical isolates, recovered by the National Public Health Laboratory in Haiti from October 2010 to January 2011 (Sjölund-Karlsson et al., 2011) and 17 toxigenic V. cholerae O1 isolates collected from surface waters in the West Department from April 2013 to March 2014 (Alam et al., 2015). These V. cholerae O1 strains, regardless of their origin (clinical or environmental) all displayed the same multidrug resistance profile: resistance to streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and nalidixic acid. The 50 V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 strains collected in our study displayed 12 different profiles of resistance but only 8.0% of them were multidrug resistant. Two multidrug-resistant strains isolated from wastewater were resistant to four and six families of antibiotics. None of the four multidrug-resistant non-O1/non-O139 isolates studied displayed the phenotypical profile of the O1 serogroup. In the Alam et al. (2015) study, all 17 isolates of V. cholerae O1 from aquatic environments were susceptible to doxycycline, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and ampicillin. In contrast, among the non-O1/non-O139 isolates in this study, some were resistant to doxycycline (1 strain), tetracycline (2 strains), chloramphenicol (3 strains), and ampicillin (6 strains), and one was resistant to erythromycin.

In another collection of 1029 V. cholerae O1 strains collected from 18 towns in Haiti from April 2012 to March 2013, the 115 V. cholerae tested by CDC Atlanta (Steenland et al., 2013) showed 100% susceptibility to ampicillin and to tetracycline, whereas a fraction of our V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 were resistant to ampicillin and tetracycline (respectively 12.0 and 4.0%).

These differences of susceptibility profile between the strains of V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 studied and the profile of O1 epidemic strains of Haiti could be partly linked to a difference in the history of exposure to antibiotics. Given that V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 serogroups isolates studied were collected in aquatic environment, we could rise the hypothesis that they have not experienced the same selection pressure as the toxigenic V. cholerae. Therefore, because doxycycline, tetracycline, and erythromycin are currently used in the treatment of diarrheal diseases in Haiti, the resistance acquired here by aquatic V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 to these antibiotics may be due to selection pressure on local enteropathogenic bacteria. Accordingly, among the four multidrug-resistant isolates of V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 detected in this study, the two strains harboring resistance to the most antibiotics (four and six different classes of antibiotics, respectively, for VCH126 and VCH3) came from raw wastewater (VCH 126 in Gonaives and VCH3 in Martissant) and these two strains were resistant to two of the three antibiotics used locally: VCH126 was resistant to tetracycline and to doxycycline and VCH3 was resistant to erythromycin and tetracycline but not to doxycycline.

In a previous study, Katz et al. discovered that the epidemic clone is poorly transformable by horizontal gene transfer, and they found no evidence that environmental strains have played any role in its evolution (Katz et al., 2013). This could explain that the susceptibility profile of the epidemic strain has not changed since the beginning of the outbreak, except the single observation of the variant 2012EL-2176 isolated from a clinical case in 2012. That single variant showed the typical resistance phenotype of the outbreak strain, but additional resistance to ampicillin had been acquired and the minimum inhibitory concentration of tetracycline had become intermediate (Folster et al., 2014). Resistance to ampicillin and tetracycline were both found in our non-O1/non-O139 isolates.

Nevertheless, to have information about the possibility of genetic exchanges between non-O1/non-O139 V. cholerae isolates and the O1 epidemic clone, deeper genetic investigations are necessary for example by whole genome sequencing, determination of the MLST profile or comparison of mutations on targeted genes (ctxB, QRDR, etc.).

The prevalence of antibiotic resistance in non-O1/non-O139 V. cholerae in an endemic zone of cholera has also been studied in Sanitpur, Assam, North East India (Bhuyan et al., 2016). A collection of 107 strains of V. cholerae (among which a single strain of O1 Ogawa) was isolated from 38 water samples (river Brahmapoutra and its tributaries, canal, tea garden) before the rainy season and during monsoon (flooding) in 2012 and 2014. Antibiotic susceptibility was tested by the same disk diffusion method, allowing comparisons with our results. The dominant resistance to sulfonamide in Haïti (70%) was consistent with the dominant resistance to sulfamethoxazole (around 60%). Resistance to two antibiotics was much more frequent in Assam than in Haïti: streptomycin (respectively around 50 vs. 10%), and nalidixic acid (around 50 vs. 4%). Resistance to three antibiotics was slightly more frequent in Assam than in Haïti: Ampicillin (around 35 vs. 12%), Erythromycin (around 15 vs. 2%), and tetracycline (around 10 vs. 4%). Two antibiotics gave opposite results: resistance to chloramphenicol was present in Haiti (6%) and absent in Assam; on the contrary, resistance to ciprofloxacin was present in Assam (5%) and absent in Haïti. These differences may be linked to sampling fluctuations but could also be linked to different choices in the two countries for diarrheal diseases and severe cholera treatment.

Thus, in cholera endemic context, the presence of V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 with reduced susceptibility or resistance to antibiotics used for human medicine in the aquatic environment may constitute a mild public health threat. Although the risk of therapeutic failure for infections by a few multidrug-resistant strains seems limited (and the incidence of such infections is still unknown in Haiti), the screening for non-O1/non-O139 serogroups should be included in surveillance programs on diarrhea outbreaks. Moreover, the hypothesis that the aquatic population of V. cholerae may constitute a reservoir of resistance genes, supplied by genetic exchanges in situ with enteric bacteria such as E. coli, which do not survive in aquatic environments, still needs to be investigated.

Conclusion

In the context of a cholera outbreak in Haiti, non-O1/non-O139 V. cholerae in surface waters showed antimicrobial patterns different from the epidemic strain: there were few multidrug-resistant strains and a high diversity of resistance profiles, including resistance to doxycycline, tetracycline and erythromycin. In contrast, according to the literature, all the clinical and environmental isolates of toxigenic serogroup O1 in Haiti were susceptible to these three antibiotics or had reduced susceptibility (tetracycline) and all presented the same specific multidrug-resistance profile.

However, the presence of acquired resistance to antibiotics among the autochthonous V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 in the aquatic environment can be construed as the result of a local selection pressure on enteric bacteria in Haiti, where the use of antibiotics is not strictly regulated.

Further research is required to address this public health issue. The ability of the autochthonous aquatic population of V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 to acquire and transfer resistance genes, especially in wastewaters, needs to be investigated. In addition, the contribution of the non-O1/non-O139 serogroups to co-infections of cholera cases, or to diarrhea cases in Haiti, should be documented as part of national surveillance programs of gastro-intestinal infections.

Author contributions

SB, contributed to the design of the work, performed the field study, contributed the acquisition, the analysis and the interpretation of the data, participated to the assays, and wrote the paper. JL, contributed to the design of the work, performed the field study and the interpretation of the data, participated to the assays, and wrote the paper. EL, contributed the acquisition, the analysis and the interpretation of the data for the work, participated to the assays, and revised the paper. RP, contributed to the design of the work, revising the work and final approval of the version to be published. SR, contributed to the design of the work, revising the work and final approval of the version to be published. EJ, contributed to the analysis and the interpretation of the data, and revised the paper. IK, contributed to the analysis and the interpretation of the data, and revised the paper. JB contributed to the acquisition of the data and revised the manuscript.

Funding

The field study was funded by a grant from the French Embassy in Haiti supporting trans-national cooperation between the French Agency for Food Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety (ANSES) and the National Laboratory of Public Health in Haiti.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nahomie Vaillant, Michelle Kati, Papaloute Vedalie, and especially Emmanuel Rossignol for their technical assistance (National Public Health Laboratory in Haiti). Olivier Barraud (UMR Inserm 1092, Limoges University, CHU of Limoges) provided the control strains and advice on integron PCR. Marie-Laure Quilici provided the field technique for safe transport of strains of V. cholerae recommended by Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

References

- Alam M. T., Weppelmann T. A., Longini I., De Rochars V. M., Morris J. G., Jr., Ali A. (2015). Increased isolation frequency of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1 from environmental monitoring sites in Haiti. PLoS ONE 10:e0124098. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam M. T., Weppelmann T. A., Weber C. D., Johnson J. A., Rashid M. H., Birch C. S., et al. (2014). Monitoring water sources for environmental reservoirs of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1, Haiti. Emerging Infect. Dis. 20, 356–363. 10.3201/eid2003.131293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Austin C., Trinanes J. A., Taylor N. G. H., Hartnell R., Siitonen A., Martinez-Urtaza J. (2013). Emerging Vibrio risk at high latitudes in response to ocean warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 73–77. 10.1038/nclimate1628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron S., Chevalier S., Lesne J. (2007). Vibrio cholerae in the environment: a simple method for reliable identification of the species. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 25, 312–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron S., Lesne J., Moore S., Rossignol E., Rebaudet S., Gazin P., et al. (2013). No evidence of significant levels of toxigenic V. cholerae O1 in the haitian aquatic environment during the 2012 rainy season. PLoS Curr. 5:ecurrents.outbreaks.7735b392bdcb749baf5812d2096d331e. 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.7735b392bdcb749baf5812d2096d331e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraud O., Baclet M. C., Denis F., Ploy M. C. (2010). Quantitative multiplex real-time PCR for detecting class 1, 2 and 3 integrons. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65, 1642–1645. 10.1093/jac/dkq167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuyan S. K., Vairale M. G., Arya N., Yadav P., Veer V., Singh L., et al. (2016). Molecular epidemiology of Vibrio cholerae associated with flood in Brahamputra River valley, Assam, India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 40, 352–356. 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bier N., Schwartz K., Guerra B., Strauch E. (2015). Survey on antimicrobial resistance patterns in Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139 in Germany reveals carbapenemase-producing Vibrio cholerae in coastal waters. Front. Microbiol. 6:1179. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli D., Salvia A. M., Sami J., Cappuccinelli P., Colombo M. M. (2006). New cluster of plasmid-located class 1 integrons in Vibrio cholerae O1 and a dfrA15 cassette-containing integron in Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated in Angola. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 2493–2499. 10.1128/AAC.01310-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli D., Spagnoletti M., Hasan N. A., Lansing S., Huq A., Colwell R. R. (2013). A new integrative conjugative element detected in haitian isolates of Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139. Res. Microbiol. 164, 891–893. 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention (1999). Laboratory Methods for the Diagnosis of Epidemic Dysentery and Cholera. Atlanta: CDC. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2010a). Methods for Antimicrobial Dilution and Disk Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria; Approved Guideline, 3rd Edn. Austin, TX. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2010b). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Suceptibility Testing, 25th Edn. CLSI supplement M100S. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2016). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Suceptibility Testing, 26th Edn. CLSI supplement M100S. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell R. R. (1996). Global climate and infectious disease: the cholera paradigm. Science 274, 2025–2031. 10.1126/science.274.5295.2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard A., Forslund A., Sandvang D., Arntzen L., Keddy K. (2001). Vibrio cholerae O1 outbreak isolates in Mozambique and South Africa in 1998 are multiple-drug resistant, contain the SXT element and the aadA2 gene located on class 1 integrons. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48, 827–838. 10.1093/jac/48.6.827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard A., Forslund A., Serichantalergs O., Sandvang D. (2000). Distribution and content of class 1 integrons in different Vibrio cholerae O-serotype strains isolated in Thailand. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 1315–1321. 10.1128/AAC.44.5.1315-1321.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshayes S., Daurel C., Cattoir V., Parienti J. J., Quilici M. L., de La Blanchardiére A. (2015). Non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia: case report and literature review. Springerplus 4, 575. 10.1186/s40064-015-1346-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cesare A., Luna G. M., Vignaroli C., Pasquaroli S., Tota S., Paroncini P., et al. (2013). Aquaculture can promote the presence and spread of antibiotic-resistant enterococci in marine sediments. PLoS ONE 8:e62838. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folster J. P., Katz L., McCullough A., Parsons M. B., Knipe K., Sammons S. A., et al. (2014). Multidrug-resistant incA/C plasmid in Vibrio cholerae from Haiti. Emerging Infect. Dis. 20, 1951–1953. 10.3201/eid2011.140889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg P., Chakraborty S., Basu I., Datta S., Rajendran K., Bhattacharya T., et al. (2000). Expanding multiple antibiotic resistance among clinical strains of Vibrio cholerae isolated from 1992-7 in Calcutta, India. Epidemiol. Infect. 124, 393–399. 10.1017/S0950268899003957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg P., Sinha S., Chakraborty R., Bhattacharya S. K., Nair G. B., Ramamurthy T. (2001). Emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant strains of Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor among hospitalized patients with cholera in Calcutta, India. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 1605–1606. 10.1128/AAC.45.5.1605-1606.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A., Ramamurthy T. (2011). Antimicrobials and cholera: are we stranded? Indian J. Med. Res. 133, 225–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. B., LaRocque R. C., Qadri F., Ryan E. T., Calderwood S. B. (2012). Cholera. Lancet 379, 2466–2476. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60436-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan N. A., Choi S. Y., Eppinger M., Clark P. W., Chen A., Alam M., et al. (2012). Genomic diversity of 2010 Haitian cholera outbreak strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E2010–E2017. 10.1073/pnas.1207359109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirk S., Huhulescu S., Allerberger F., Lepuschitz S., Rehak S., Weil S., et al. (2016). Necrotizing fasciitis due to Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139 after exposure to Austrian bathing sites. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 128, 141–145. 10.1007/s00508-015-0944-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochhut B., Lotfi Y., Mazel D., Faruque S. M., Woodgate R., Waldor M. K. (2001). Molecular analysis of antibiotic resistance gene clusters in Vibrio cholerae O139 and O1 SXT constins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 2991–3000. 10.1128/AAC.45.11.2991-3000.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hombach M., Courvalin P., Böttger E. C. (2014). Validation of antibiotic susceptibility testing guidelines in a routine clinical microbiology laboratory exemplifies general key challenges in setting clinical breakpoints. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 3921–3926. 10.1128/AAC.02489-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino K., Yamasaki S., Mukhopadhyay A. K., Chakraborty S., Basu A., Bhattacharya S. K., et al. (1998). Development and evaluation of a multiplex PCR assay for rapid detection of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 20, 201–207. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanaga M., Toma C., Miyazato T., Insisiengmay S., Nakasone N., Ehara M. (2004). Antibiotic resistance conferred by a class I integron and SXT constin in Vibrio cholerae O1 strains isolated in laos. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 2364–2369. 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2364-2369.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L. S., Petkau A., Beaulaurier J., Tyler S., Antonova E. S., Turnsek M. A., et al. (2013). Evolutionary dynamics of Vibrio cholerae O1 following a single-source introduction to Haiti. mBio 4:e00398–13. 10.1128/mBio.00398-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P. A., Patterson J., Karpagam P. (2009). Multiple antibiotic resistance profiles of Vibrio cholerae non-O1 and non-O139. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 62, 230–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukinmaa S., Mattila K., Lehtinen V., Hakkinen M., Koskela M., Siitonen A. (2006). Territorial waters of the Baltic Sea as a source of infections caused by Vibrio cholerae non-O1, non-O139: report of 3 hospitalized cases. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 54, 1–6. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos A. P., Srinivasan A., Carey R. B., Carmeli Y., Falagas M. E., Giske C. G., et al. (2012). Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 268–281. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti E., Variatza E., Balcazar J. L. (2014). The role of aquatic ecosystems as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance. Trends Microbiol. 22, 36–41. 10.1016/j.tim.2013.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon M. P., Mintz E. D., Tauxe R. V. (2009). Cholera, in Bacterial Infections of Humans: Epidemiology and Control, eds Brachman S. P., Abrutyn E. (Boston, MA: Springer; ), 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Muic V. (1990). Rapid quantitative test for Vibrio cholerae in sewage water based on prolongated incubation at an elevated temperature. Period. Biol. 92, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Nandi B., Nandy R. K., Mukhopadhyay S., Nair G. B., Shimada T., Ghose A. C. (2000). Rapid method for species-specific identification of Vibrio cholerae using primers targeted to the gene of outer membrane protein OmpW. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38, 4145–4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei R., Kim S. C., Carlson K. H., Pruden A. (2006). Effect of River Landscape on the sediment concentrations of antibiotics and corresponding antibiotic resistance genes (ARG). Water Res. 40, 2427–2435. 10.1016/j.watres.2006.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popowska M., Rzeczycka M., Miernik A., Krawczyk-Balska A., Walsh F., Duffy B. (2012). Influence of soil use on prevalence of tetracycline, streptomycin, and erythromycin resistance and associated resistance genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 1434–1443. 10.1128/AAC.05766-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raissy M., Moumeni M., Ansari M., Rahimi E. (2012). Antibiotic resistance pattern of some Vibrio strains isolated from seafood. Iran. J. Fish. Sci. 11, 618–620. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo L., Manaia C., Merlin C., Schwartz T., Dagot C., Ploy M. C., et al. (2013). Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes spread into the environment: a review. Sci. Tot. Environ. 447, 345–360. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoolnik G. K., Yildiz F. H. (2000). The complete genome sequence of Vibrio cholerae: a tale of two chromosomes and of two lifestyles. Genome Biol. 1, reviews1016.1–reviews1016.3. 10.1186/gb-2000-1-3-reviews1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjölund-Karlsson M., Reimer A., Folster J. P., Walker M., Dahourou G. A., Batra D. G., et al. (2011). Drug-resistance mechanisms in Vibrio Cholerae O1outbreak strain, Haiti, 2010. Emerging Infect. Dis. 17, 2151–2154. 10.3201/eid1711.110720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland M. W., Joseph G. A., Lucien M. A. B., Freeman N., Hast M., Nygren B. L., et al. (2013). Laboratory-confirmed cholera and rotavirus among patients with acute diarrhea in four hospitals in Haiti, 2012-2013. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hygiene 89, 641–646. 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talkington D., Bopp C., Tarr C., Parsons M. B., Dahourou G., Freeman M., et al. (2011). Characterization of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae from Haiti, 2010–2011. Emerging Infect. Dis. 17, 2122–2129. 10.3201/eid1711.110805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]