Abstract

Purpose: There is evolving evidence that children and adolescents with gender dysphoria have higher-than-expected rates of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), yet clinical data on ASD among youth with gender dysphoria remain limited, particularly in North America. This report aims to fill this gap.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective review of patient chart data from 39 consecutive youth ages 8 to 20 years (mean age 15.8 years, natal male: n = 22, natal female: n = 17) presenting for evaluation at a multidisciplinary gender clinic in a large U.S. pediatric hospital from 2007 to 2011 to evaluate the prevalence of ASD in this patient population.

Results: Overall, 23.1% of patients (9/39) presenting with gender dysphoria had possible, likely, or very likely Asperger syndrome as measured by the Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale (ASDS).

Conclusion: These findings are consistent with growing evidence supporting increased prevalence of ASD in gender dysphoric children. To guide provision of optimal clinical care and therapeutic intervention, routine assessment of ASD is recommended in youth presenting for gender dysphoria.

Keywords: : Asperger syndrome, autism spectrum disorder, gender dysphoria, transgender, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth

Introduction

There is evolving evidence that children and adolescents with gender dysphoria have higher than expected rates of autism spectrum disorder (ASD).1–3 Gender dysphoria denotes a persistent incongruence between one's biologic sex and current gender identity causing clinically significant distress and impairment.4 The association of gender dysphoria with ASD, with cases often categorized as Asperger syndrome (AS), was initially reported in a series of case reports.5–7 The association was measured more formally in a Dutch study which reported a 7.8% prevalence of ASD in patients presenting for evaluation at a gender dysphoria clinic,8 a rate much higher than expected based on the prevalence of ASD in the general population. In addition, children with ASD seen at a large U.S. hospital-based neuropsychology clinic were 7.59 times more likely than non-referred children to have gender variance as measured by the parent-reported Child Behavior Checklist.9

However, clinical data on ASD among youth with gender dysphoria remain limited, particularly in North America where no published studies, to our knowledge, have formally evaluated the prevalence of children and adolescents with ASD presenting with gender dysphoria. The current study aimed to fill this gap by providing a descriptive analysis of ASD data from youth patients referred to a multidisciplinary gender clinic in a large U.S. pediatric hospital.

Methods

We reviewed clinical data from 39 consecutive patients ages 8 to 20 years (mean age 15.8 years, natal male: n = 22, natal female: n = 17) presenting for evaluation at a multidisciplinary gender clinic from 2007 to 2011 based in a large U.S. pediatric hospital. All study activities were approved by the Boston Children's Hospital Institutional Review Board, and patient data were protected by use of sound research methods and use of de-identified data.

As part of an initial evaluation, a single clinic psychologist performed a battery of psychological assessments, routinely administering the Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale (ASDS)10 in an attempt to identify children who may have co-occurring gender dysphoria and ASD. The ASDS was designed for use in children ages 5-to-18 years and was validated in a sample of 115 children with the diagnosis of AS.11 It is a parent-completed, pen-and-paper measure containing 50 statements that are rated as observed or not observed. The statements describe AS-typical behaviors within 5 subscales: language (9 items), social (13 items), maladaptive (11 items), cognitive (10 items), and sensorimotor (7 items). For example, an item within the social subscale, “Avoids or limits eye contact,” provides the parent with choices “Observed” or “Not observed.” The total number of observed items within the subscale yields the subscale's raw score with corresponding percentiles within each subscale. Adding together these subscale raw scores yields a total raw score that is converted into an Asperger Syndrome Quotient (ASQ). The ASQ translates to a “Probability of Asperger Syndrome.” Probabilities are expressed as “Very likely” (ASQ >110), “Likely” (ASQ 90–110), “Possibly” (ASQ 80–89), “Unlikely” (ASQ 70–79), and “Very unlikely” (ASQ ≤69).10 The ASDS was chosen as a clinical tool for our program because it could be administered and scored quickly, serving as a screening tool for ASD.

Data were extracted manually from individual patient charts by one member of the study team and entered into Excel. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, standard deviations) were conducted.

Results

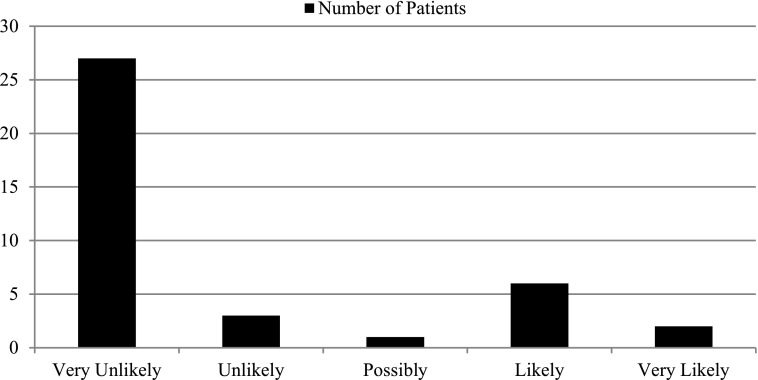

Overall, 9 of the 39 participants (23.1%) had an ASQ above 80, corresponding to a “Probability of Asperger Syndrome” of “Possibly” (n = 1), “Likely” (n = 6), or “Very likely” (n = 2) (Figure 1). Of these nine participants scoring highly on the ASDS, 5 were assigned a male sex at birth and 4 were assigned a female sex at birth. Average age at evaluation of the high ASQ group was 16.2 years (range 12.0–18.8). The prevalence of ASDS among natal males (22.7%, n = 5/22) and natal females (23.5%, n = 4/17) in our patient population was not significantly different (Fisher's exact test P = 0.95).

FIG. 1.

Probability of Asperger Syndrome as determined by the Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale.

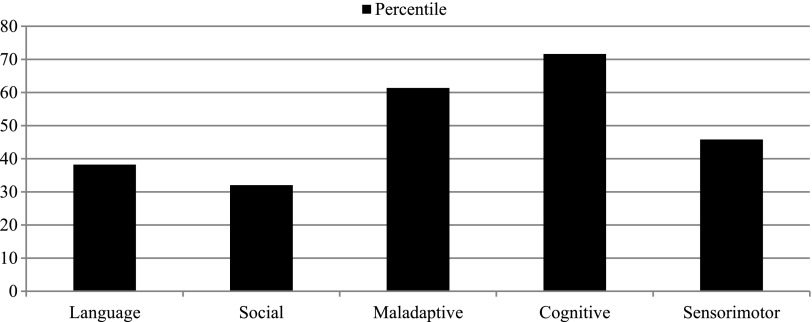

Prior to presenting to the gender clinic, one patient had a long-standing diagnosis of autism, one had a long-standing diagnosis of Asperger syndrome, and two had been recently given a diagnosis of Asperger syndrome by a referring psychologist. Subscale analysis of the 9 patients with high ASQ scores demonstrates highest scores in the cognitive subscale, followed by the maladaptive subscale (Figure 2). Review of documentation would suggest that the identified patients represent a range of autism severity with more representation in the high-functioning end of the clinical spectrum. None of the four patients already diagnosed with an ASD had been diagnosed with other mental health disorders. Of the five patients not previously diagnosed with an ASD, four had been diagnosed with other mental health disorders (Table 1). Comparison of rates of co-morbid mental health disorders between patients with high versus low ASQ scores was not performed; previous description of this clinic's patient population demonstrated a rate of significant psychiatric history at presentation at 44.3%.12

FIG. 2.

Mean Subscale Percentile* Scores of the 9 Patients with ASQ Scores >80. *Percentile refers to the percentile score described on the Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale scoring form.

Table 1.

Description of 9 Patients with ASQ >80

| Age (years) | Sex assigned at birth | ASQ | ASQ Interpretation^ | ASD Diagnosis | Other mental health diagnoses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17.8 | F | 116 | Very likely | Asperger syndrome* | — |

| 15.6 | M | 111 | Very likely | Asperger syndrome | — |

| 12.0 | M | 101 | Likely | Autism | — |

| 12.5 | M | 107 | Likely | — | Learning Disorder, ADHD, Bipolar Disorder |

| 14.8 | M | 103 | Likely | — | ADHD, Selective Mutism, PTSD |

| 18.1 | F | 97 | Likely | Asperger syndrome* | — |

| 18.8 | F | 97 | Likely | — | Anxiety Disorder |

| 18.7 | M | 92 | Likely | — | — |

| 17.1 | F | 82 | Possibly | — | Dysthymic Disorder, Social Phobia |

Diagnosed by referring psychologist during assessment for gender dysphoria.

Likelihood of diagnosis of Asperger syndrome based on ASQ.

ASQ, Asperger syndrome quotient; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

This is the first report of formal screening for ASD in patients presenting to a North American child and adolescent gender clinic. Our finding, that 23% of patients presenting with gender dysphoria had possible, likely, or very likely Asperger syndrome as measured by the ASDS, is consistent with growing evidence of increased prevalence of ASD in gender dysphoric children.1–3,8 This number is higher than the previously published co-occurrence rate of 7.8% in the Dutch pediatric gender clinic, however the numbers should not be compared directly since we used a screening tool while the Dutch group used a diagnostic test, the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders—10th Revision.8 It is interesting to note the near equal rate of positively screened males and females. This finding conflicts with the typical male prevalence of ASD.

The evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria is guided by professional guidelines or standards of care.13,14 These guidelines suggest evaluation by a mental health professional who not only explores the diagnosis of gender dysphoria, but who also assesses for co-occurring mental health conditions. Anxiety, depression, and suicidality are common in children and adolescents presenting to gender clinics.15,16 The psychological evaluation performed is not standardized, with different clinics performing diverse batteries of psychological testing.12,17,18 Our data support inclusion of ASD screening as part of any comprehensive gender assessment, especially as diagnosis of ASD has implications for management of gender dysphoria. For example, a patient with ASD and gender dysphoria may require specialized psychosocial interventions, focused on navigating unique social challenges encountered during hormonal and social transition from the natal sex to the affirmed gender. Youth have the right to appropriate assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of both ASD and gender dysphoria to ensure optimal clinical care.

A limitation of this study is that we report results of a screening test that is not validated as an ASD diagnostic tool in the absence of other confirmatory information. It is important to restate that the ASDS was not validated in a general population-based sample, but rather in a sample of 115 children with the diagnosis of AS. This limits our ability to know how closely we are measuring true ASD. For example, some items on the ASDS may be naturally observed in non-ASD gender dysphoric youth. Specifically, an item on the cognitive subscale “appears to be aware that he or she is different from others,” and an item on the maladaptive subscale “does not change behavior to match the environment,” might capture expected observations in a gender dysphoric child. Thus, scrupulous attention to symptomology during ASD diagnostic evaluation of gender non-conforming youth is essential to minimize any risk of misclassifying gender dysphoric youth with high functioning ASD due to symptom overlap (e.g., feeling different from peers, social isolation, etc.). Importantly, certain symptoms may be associated with both diagnoses, but stem from vastly different origins. Another consideration is the potential for presentation bias. First, children with ASD may be more likely to express their gender dysphoria than children without ASD. ASD may minimize awareness of social stigma, the same stigma that might cause non-ASD children to repress gender dysphoria. Second, children with co-occurring ASD and gender dysphoria may be more likely to be referred to a specialty center than other children with gender dysphoria, who may be managed locally. Therefore, our findings describe rates of positively screened ASD in children presenting for medical assessment and management of gender dysphoria to a specialty referral center, as opposed to the general co-occurrence of ASD and gender dysphoria. The true relationship of ASD and gender dysphoria requires a population-based study design. Finally, this is a retrospective chart review and results should be further examined using prospective research methods.

Conclusion

Our findings are consistent with growing evidence supporting increased prevalence of ASD in gender dysphoric children. Future research is needed to validate measures of ASD for use with a gender dysphoric patient population. In addition, longitudinal follow-up studies of co-occurring gender dysphoria and ASD will allow for better quantification of the problem and improved understanding of etiological factors. Differences in androgen exposures on the developing fetal brain have been suggested as a potential contributor in gender development19–22 as well as in the development of ASD.23,24 Genetic factors have also been implicated in both ASD25 and gender dysphoria.26 In addition, it has been proposed that the social rigidity typical of ASD contributes to inflexibility of gender and contributes to increased prevalence of ASD in gender dysphoric children.8 Gaining scientific and clinical insight into children and adolescents with co-occurring gender dysphoria and ASD could advance understanding of development of both gender and autism, as well as guide diagnostic practices, clinical care, and therapeutic intervention. To guide provision of optimal clinical care and therapeutic intervention, we recommend routine assessment of ASD in youth presenting for gender dysphoria.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Reisner's time was partially supported by NIMH R01MH094323. Dr. Shumer's time was partially supported by NICHD 1T32HD075727-01. There are no other contributors to acknowledge.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Lemaire M, Thomazeau B, Bonnet-Brilhault F: Gender identity disorder and autism spectrum disorder in a 23-year-old female. Arch Sex Behav 2014;43:395–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Schalkwyk GI, Klingensmith K, Volkmar FR: Gender identity and autism spectrum disorders. Yale J Biol Med 2015;88:81–83 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs LA, Rachlin K, Erickson-Schroth L, Janssen A: Gender dysphoria and co-occurring autism spectrum disorders: Review, case examples, and treatment considerations. LGBT Health 2014;1:277–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallucci G, Hackerman F, Schmidt CW, Jr: Gender identity disorder in an adult male with Asperger's syndrome. Sex Disabil 2005;23:35–40 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tateno M, Tateno Y, Saito T: Comorbid childhood gender identity disorder in a boy with Asperger syndrome. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2008;62:238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinow O: Paraphilia and transgenderism: A connection with asperger disorder? Sex Relation Ther 2009;24:143–151 [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Vries AL, Noens IL, Cohen-Kettenis PT, et al. : Autism spectrum disorders in gender dysphoric children and adolescents. J Autism Dev Disord 2010;40:930–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strang JF, Kenworthy L, Dominska A, et al. : Increased gender variance in autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Sex Behav 2014;43:1525–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myles BS, Bock S, Simpson R: Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell JM: Diagnostic assessment of Asperger's disorder: A review of five third-party rating scales. J Autism Dev Disord 2005;35:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spack NP, Edwards-Leeper L, Feldman HA, et al. : Children and adolescents with gender identity disorder referred to a pediatric medical center. Pediatrics 2012;129:418–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, et al. : Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:3132–3154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. : Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgenderism 2012;13:165–232 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards-Leeper L, Spack NP: Psychological evaluation and medical treatment of transgender youth in an interdisciplinary “Gender Management Service” (GeMS) in a major pediatric center. J Homosex 2012;59:321–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallien MS, Swaab H, Cohen-Kettenis PT: Psychiatric comorbidity among children with gender identity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:1307–1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zucker KJ, Wood H: Assessment of gender variance in children. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2011;20:665–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tishelman AC, Kaufman R, Edwards-Leeper L, et al. : Serving transgender youth: Challenges, dilemmas, and clinical examples. Prof Psychol Res Prac 2015;46:37–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berenbaum SA, Beltz AM: Sexual differentiation of human behavior: Effects of prenatal and pubertal organizational hormones. Front Neuroendocrinol 2011;32:183–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hines M: Prenatal endocrine influences on sexual orientation and on sexually differentiated childhood behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol 2011;32:170–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shumer DE, Spack NP: Current management of gender identity disorder in childhood and adolescence: Guidelines, barriers and areas of controversy. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2013;20:69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron-Cohen S, Lombardo MV, Auyeung B, et al. : Why are autism spectrum conditions more prevalent in males? PLoS Biol 2011;9:e1001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knickmeyer R, Baron-Cohen S, Fane B, et al. : Androgens and autistic traits: A study of individuals with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Horm Behav 2006;50:148–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voracek M: Fetal androgens and autism. Br J Psychiatry 2010;196:416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miles JH: Autism spectrum disorders–A genetics review. Genet Med 2011;13:278–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heylens G, De Cuypere G, Zucker KJ, et al. : Gender identity disorder in twins: A review of the case report literature. J Sex Med 2012;9:751–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]