Abstract

Purpose: Research linking family rejection and health outcomes in sexual minority people is mostly limited to North America. We assessed the associations between negative treatment by family members and depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, suicidality, and tobacco/alcohol use in sexual minority women (SMW) in Viet Nam.

Methods: Data were from an anonymous internet survey (n = 1936). Latent class analysis characterized patterns of negative treatment by family members experienced by respondents. Latent class with distal outcome modeling was used to regress depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, suicidality, and tobacco/alcohol use on family treatment class, controlling for predictors of family treatment and for two other types of sexual prejudice.

Results: Five latent family treatment classes were extracted, including four negative classes representing varying patterns of negative family treatment. Overall, more than one negative class predicted lower life satisfaction, more depressive symptoms, and higher odds of attempted suicide (relative to the non-negative class), supporting the minority stress hypothesis that negative family treatment is predictive of poorer outcomes. Only the most negative class had elevated alcohol use. The association between family treatment and smoking status was not statistically significant. The most negative class, unexpectedly, did not have the highest odds of having attempted suicide, raising a question about survivor bias.

Conclusion: This population requires public health attention, with emphasis placed on interventions targeting the family to promote acceptance and to prevent negative treatment, and interventions supporting those SMW who encounter the worst types of negative family treatment.

Keywords: : family rejection, latent class model, mental health, sexual minority women (SMW), substance use, suicidality

Introduction

Research on sexual minority mental health has been primarily conducted in North America and Europe, with ample evidence of a higher risk of depression, anxiety, suicidality, and substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) populations compared with heterosexuals (see meta-analyses1–3). In Asia, similar research has been limited to relatively resource-rich countries/areas (Taiwan, Thailand, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Japan), with several studies documenting higher depression, substance use, and suicidality, and lower quality of life in lesbian women and gay men.4–8 In Viet Nam, a relatively resource-poor Asian country, to the best of our knowledge, sexual minority health research has been limited to the study of HIV risk in men who have sex with men. Based on recent evidence of prevalent family disapproval and negative treatment of Vietnamese sexual minority women (SMW),9,10 this study assesses negative family treatment as a risk factor for poor health and well-being in this population.

The study draws from the minority stress model,1,11 which identifies stressors related to sexual minority status on a distal-to-proximal continuum—from the experience of enacted sexual stigma (or “prejudice events”1,11), to the expectation of such events, to the internalization of sexual stigma, and to the concealment of one's sexual minority status—and proposes that such stressors place sexual minority people at higher risk of poor health. This study addresses the distal among these stressors, and it focuses on the family environment. Acts of prejudice by family members that an SMW experiences—such as her parents and siblings pressuring her to leave her girlfriend and meet male suitors, or her mother threatening suicide if she will not stop seeing women9—are likely to affect her mental health negatively. A number of studies have linked the experience of family rejection of LGB identity in adolescence to depressive,12,13 anxiety,12 or a broad range of mental health symptoms14; to suicidal ideation12,13 and attempts13,15; to cigarette, alcohol, marijuana,16 or illegal substance use13,17; and to substance/alcohol-related social or legal problems.13 In addition, parent discouragement of gender atypical behavior in LGB adolescents has been linked to poorer mental health18 and to suicide attempts.19 These studies include several samples of youth (aged up to 21),14–19 a sample of young adults (aged 21–25),13 and one adult sample with a wide age range (18–75).12 We are not aware of any research that examined the association between family rejection in adulthood and health. All of the studies cited earlier dealt with LGB in the United States; two also included Canadians14,15 and New Zealanders.15

Negative family treatment of Vietnamese SMW

In Vietnamese culture, which is influenced by Confucian values of hierarchy and patriarchy, heterosexual marriage and reproduction is considered a social rule and a filial duty.20 Vietnamese women are strongly expected to “get a husband” and have children, usually at a relatively young age. Same-sex relationships defy this social script, and are thus difficult for families to accept in their children, including adolescent and adult children. A qualitative study with SMW in Ha Noi from 2009 highlighted significant challenges in SMW's relationships with their parents.9 Most respondents reported concealing their same-sex relationships from their families to protect themselves from rejection and to protect their families from pain and suffering. When parents found out, most disapproved, because they: perceived homosexuality as abnormal or sick; feared negative judgment by the extended family or community; grieved the loss of expected future grandchildren; and worried about their daughter's life and future. In a sample of Vietnamese SMW and transmen (n = 2664), more than two thirds reported having experienced family disapproval of their relationships with women and/or family pressure to have a boyfriend, to get married, or to be more feminine.10 Nearly one fourth reported having experienced one or more oppressive family actions, such as family members locking them up or asking a doctor for treatment to stop their attraction to women. A latent class analysis (LCA) of such data suggested highly distinct subgroups, ranging from very little to exceptionally high levels of such negative family treatment.10

Using a subset of these data including SMW only, the present study related a latent categorical variable representing heterogeneity in family treatment experience to health and well-being. We hypothesized that SMW with worse family treatment experience on average had higher depressive symptoms and lower life satisfaction, and were more likely to smoke, to drink heavily, and to have attempted suicide. In addition to assessing these associations, the study was intended to help identify which subgroups of SMW (characterized by family treatment experience) are most in need of interventions to protect their health and well-being.

Methods

Data source

Data were from a 2012 anonymous internet-based survey. Participants were recruited through advertisements on Vietnamese SMW websites, and they were screened using three statements: “You are over 18 years old,” “You are a woman,” and “You have loved another woman (/other women)”—the Vietnamese word yêu (love) implies either having had romantic/sexual feelings for or having been in a relationship with someone. Participants were provided with informed consent material (covering the study's topics and participants’ rights) and indicated consent on the survey webpage before answering the questionnaire. The survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and has been described elsewhere.10 The current analyses used data from survey respondents who lived in Viet Nam who answered a set of questions about negative family treatment, but they were restricted to SMW who identified as lesbian or bisexual, or who reported being unsure about their sexual identity (n = 1936). Survey respondents who identified as heterosexual women (56), who reported “other” sexual identity (24), who identified as transmen (574), or whose gender identity was not reported (29)i were excluded.

Measures

The survey included a section with an umbrella question, “Have your parents or other people in your extended family ever given you the following types of treatment—because they knew or suspected that you loved a woman, or because they thought you were not very ‘feminine’?” The 19 yes/no items under this question (derived from prior qualitative research with Vietnamese SMW9) included three about general disapproval and pressure to change and 16 representing a variety of aggressive family behaviors (see item wording in Fig. 1). These items were summarized in a latent categorical variable representing subtypes of negative family treatment experience (see Analyses section), which served as the independent variable of interest. Either a latent continuous or categorical variable would be appropriate for evaluating the association between family treatment and the dependent variables, whereas a latent categorical variable is useful for identifying subgroups of SMW that may be more in need of intervention.

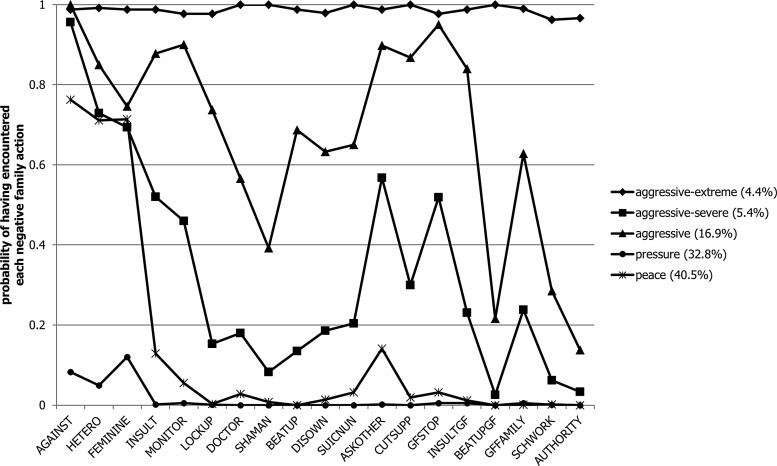

FIG. 1.

Five latent classes* of negative family treatment (class prevalence) with class-specific probabilities of having encountered each negative family action** (n = 1936).

*Bayesian information criterion, consistent Akaike's information criterion, Bayes factor, and approximate correct model probability all favor the five-class solution over other solutions with one to eight classes. Results of likelihood ratio tests vary: The Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test suggests four classes, but the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test does not suggest a specific solution. Overall, the five-class solution has the most support. This solution also has very good class separation, with entropy = 0.87 and correct classification probabilities ranging from 0.86 to 0.99. See Masyn25 for a detailed explanation of class enumeration using these statistics.

- AGAINST: Oppose respondent (R) loving women.

- HETERO: Pressure R to have boyfriend or get married.

- FEMININE: Pressure R to be more feminine.

- INSULT: Insult R.

- MONITOR: Monitor R's activities and time (to keep her from seeing her female partner).

- LOCKUP: Lock R up or take/send R somewhere else (to prevent her from seeing her female partner).

- DOCTOR: Ask a hospital/doctor/healer to “treat” R to stop her loving women.

- SHAMAN: Ask a shaman to help R to stop loving women (or to get married).

- BEATUP: Beat R up.

- DISOWN: Disown R or throw her out of the house.

- SUICNUN: Threaten to commit suicide or to join a monastery (if R would not change) or actually attempt suicide or join a monastery.

- ASKOTHER: Ask others to persuade R to change.

- CUTSUPP: Reduce or stop providing support to R (including financial support, support for education, etc.).

- GFSTOP: Ask R's female partner to stop the relationship.

- INSULTGF: Insult R's female partner.

- BEATUPGF: Beat up R's female partner.

- GFFAMILY: Tell R's female partner's family.

- SCHWORK: Inform R's or her female partner's school or workplace of their relationship.

- AUTHORITY: Ask local authorities or police to intervene in R's relationship with her female partner.

Five dependent variables were examined. Depressive symptoms were measured using an adapted Vietnamese version21 of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)22 with a 0-to-27 range (Cronbach's alpha = 0.85 in this sample). Life satisfaction was measured using an adapted Vietnamese version23 of the Personal Wellbeing Index for adults (PWI-A),24 capturing satisfaction with standards of living, health, achievements in life, personal relationships, love life, safety, work or school, community integration, and future prospects, with a 0-to-100 range (Cronbach's alpha = 0.87). Lifetime suicide attempt history was an ordinal variable (having had zero, one, or more than one suicide attempts). Current smoking (vs. not currently smoking, regardless of whether the respondent had ever smoked in the past) and heavy drinking (having consumed four or more alcoholic drinks on at least 1 day in the past 30 days) were binary variables.

Analyses controlled for variables that had been found to be associated with negative family treatment, including age, sexual identity (ascertained through a survey item phrased “You consider yourself” followed by the sexual identities as response options), religion, self-rated family economic status, urban residence, and geographical region,10 as well as residence with family. In addition, we controlled for two types of sexual prejudice: (1) discrimination ever experienced outside the family (a count of up to nine items, derived from data from the prior qualitative study, representing lifetime experience of discrimination at school, discrimination at work or when applying for work, and discrimination with regard to housing and discrimination in social interactions) and (2) whether the respondent had ever lost a close friendship, in both cases “because people knew or thought you loved women, or thought you were not very ‘feminine.’”

Analyses

First, to characterize family treatment, LCA was conducted on the negative family behavior items. The purpose was to identify latent subgroups (classes) of SMW with similar patterns of family treatment experience. More precisely, LCA assumes that there are a certain number of classes, and that respondents in the same class share a set of probabilities of having experienced the family behaviors, but these sets of probabilities vary across the classes. The number of classes was determined based on comparing models with different numbers of classes that could be fit, considering (1) a range of fit statistics and likelihood ratio tests (which suggest how many classes should be extracted for a solution that explains the data), (2) the meaning of the classes (whether the extracted classes are interpretable), and to a lesser extent (3) the degree of class separation (higher class separation suggests the classes are more distinct). See Masyn25 for a detailed description of these methods. This initial part of the analysis was similar to the LCA in the previously published article10; the difference was that the previous article used a broader sample, which also included transmen and SMW who identified as heterosexual.

To model the outcomes variables, we used latent class with distal outcome (LCD) modeling with Vermunt's correction for class uncertainty.26–28 Specifically, based on the LCA, each individual's most likely class (modal class) was predicted, and average classification error probabilities (e.g., probability of being in class 2 given modal class 1) were estimated. The LCD model (the model predicting the outcome) then used modal class as the only indicator of the latent class variable and incorporated classification error probabilities into the likelihood function to be maximized. Linear models were fit for continuous outcomes. Logistic models were fit for binary outcomes. An ordered logistic model was fit for the ordinal suicide attempt outcome. The ordered logistic model makes the proportional odds assumption; in this case, the assumption was that the odds ratio (OR) of having ever, versus never, attempted suicide is equal to the OR of having made more-than-one versus zero-to-one suicide attempts. This assumption was deemed appropriate, because the ORs from separate analyses, treating having ever (vs. never) attempted suicide and having made more-than-one (vs. zero-to-one) suicide attempts as two binary outcomes, were very similar. The control variables were included in all LCD models. For depressive symptoms score, which is right skewed, confidence intervals (CI) were obtained via bootstrapping (with 500 bootstrap samples). Analyses were conducted using Mplus version 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA).29

Even though we conceptualized some variables as risk factors and others as outcomes, with cross-sectional data (which we comment on in the Discussion section), this modeling exercise only sheds light on associations, not on cause–effect relationships. Therefore, when presenting modeling results, we use association language (e.g., “X is associated with Y” or “X is predictive of Y”), not causal language (e.g., “X causes Y” or “the effect of X on Y”). For the sake of brevity, however, we use the term “outcomes” when referring to the dependent variables in a generic way.

The original sample consisted of 1981 SMW. Missing covariate data were limited. We used missing indicators on covariates with the most missingness, family economic status (missing 2.8%), and discrimination outside the home (2.1%); we excluded observations missing other covariates, leaving an analysis sample of 1936 (97.7%). Regarding outcome data, life satisfaction and depressive symptoms had minimal missing (0.5%, 0.4%). Smoking, heavy drinking, and lifetime suicide attempt history had data missing by design (about 18%, because these questions were not asked until day 4 after survey launch) and limited non-response (0.8%, 1.2%, and 3.6%). We used full-information maximum likelihood estimation, which provides unbiased estimates, assuming missing data on outcomes were missing at random.30

Results

In LCA, according to the fit statistics, the five-class solution best fits the data. The classes were well separated. Figure 1 presents, for each of the five classes, the probabilities of having experienced each of the 19 negative family behaviors. We named the classes as followsii: peace (i.e., having had relative peace, with almost no negative treatment); pressure (i.e., having experienced pressure to change, but almost no “aggressive” family behavior—see next); aggressive (i.e., having experienced pressure plus some aggressive family behaviors such as locking up, beating up, disowning, or insulting the female partner); aggressive–severe (i.e., having experienced many aggressive family behaviors); and aggressive–extreme (i.e., having encountered most of the 19 negative behaviors). These five classes, in the order listed earlier, were estimated to make up 40.5%, 32.8%, 16.9%, 5.4%, and 4.4% of the sample, respectively. When referring to the classes other than peace collectively, we use “negative classes” for short.

In this sample, average life satisfaction index was 59.1 out of 100 (standard deviation [SD] = 18.1); average depressive symptoms score was 9.12 out of 27 (SD = 6.20). Nearly 17% of the sample reported having attempted suicide, including 8% who had made more than one attempt. Seventeen percent and 30% reported smoking and heavy drinking, respectively. The sample was predominantly young (80% aged 18–25) and urban (three-fourths lived in major cities); and half identified as lesbian (see Table 1 for all variables used in LCD modeling). It should also be noted that the sample was relatively highly educated, with half (50.2%) having some college education, another 24.5% having some post-high-school education (similar to community college), another 9% having finished high school, and 14% having dropped out of high school.

Table 1.

| Exposure | Numberc | % |

|---|---|---|

| Latent family treatment class | ||

| Peace | 784 | 40.5 |

| Pressure | 635 | 32.8 |

| Aggressive | 327 | 16.9 |

| Aggressive-severe | 105 | 5.4 |

| Aggressive-extreme | 86 | 4.4 |

| Continuous outcomes | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction (PWI-A, range 0–100) | 59.1 | 18.1 |

| Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9, range 0–27) | 9.1 | 6.20 |

| Categorical outcomes | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Lifetime suicide attempts (n = 1526)d | ||

| None | 1270 | 83.2 |

| One | 133 | 8.7 |

| More than one | 123 | 8.1 |

| Current smoking (n = 1544)d | 268 | 17.4 |

| Heavy drinking past month (n = 1534)d | 484 | 30.0 |

| Categorical covariates | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Agee | ||

| 18–20 | 744 | 38.4 |

| 21–25 | 805 | 41.6 |

| 26 or older | 387 | 20.0 |

| Sexual identity | ||

| Lesbian | 1079 | 53.5 |

| Bisexual | 557 | 27.6 |

| Unsure | 300 | 14.9 |

| Affiliation with a religion | 952 | 49.2 |

| Family economic status | ||

| Rich | 70 | 3.7 |

| Comfortable living | 558 | 29.5 |

| Sufficient living | 1144 | 60.4 |

| Poor | 121 | 6.4 |

| Living with one's family | 1542 | 79.6 |

| Urban residence | 1481 | 76.5 |

| Geographical region | ||

| Red river delta | 298 | 15.4 |

| Northern mountains | 35 | 1.8 |

| Central region | 163 | 8.4 |

| South-east region | 1195 | 61.7 |

| Mekong delta | 245 | 12.7 |

| Lost a close friend due to prejudice | 252 | 13.0 |

| Continuous covariate | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Prejudice-based discrimination | 0.85 | 1.31 |

This sample was a sub-sample of the sample used in a previously published article,10 which combined SMW (including a broader range of sexual identities) and transmen.

The sum of each variable's categories may not add up to exactly the sample size, mostly due to missing data. For family treatment, the total is 1937 instead of 1936 due to rounding of the estimated (not observed) numbers of SMW in the classes.

The numbers of respondents in the family treatment classes are not observed, but estimated by the latent class analysis.

Sample sizes for suicidality and smoking/heavy drinking were smaller, because these questions were activated in the online survey 4 days after survey launch. Proportions were based on dividing by the number of participants with available data.

For variable age, the mean is 22.6 years, the range is from 18 to 52 years, and the SD is 4.53 years.

PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PWI-A, Personal Wellbeing Index for adults; SD, standard deviation; SMW, sexual minority women.

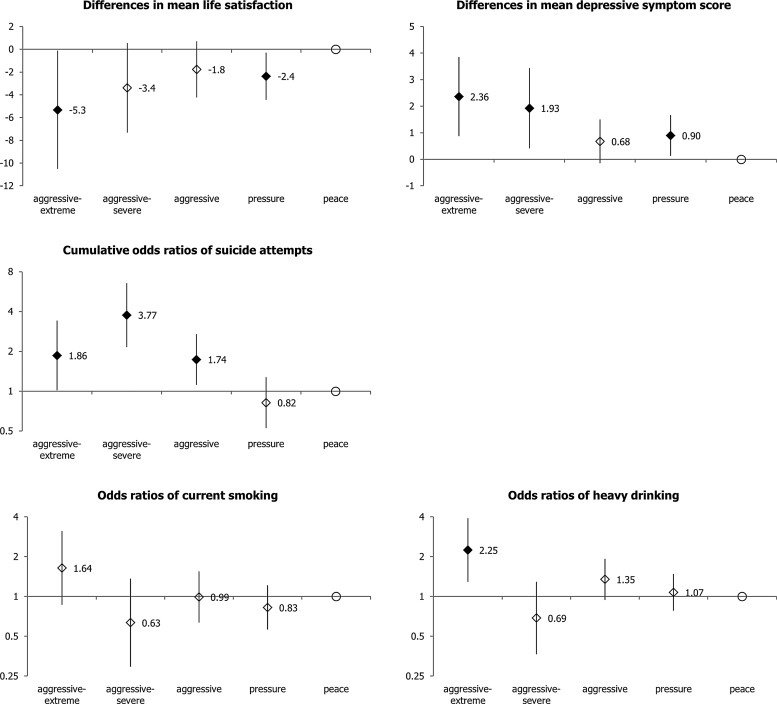

Table 2 presents full results from the LCD models. The adjusted associations of family treatment with the outcomes from these models are plotted in Figure 2. Next, we summarize findings in terms of mean differences (or coefficients) and ORs (or exponentiated coefficients) while comparing family treatment classes—all adjusted for other variables in the model.

Table 2.

Models Predicting Outcome Variables Using Family Treatment Class and Covariates

| Life satisfaction | Depressive symptoms | Lifetime suicide attempts | Current smoking | Heavy drinking past month | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a.coef. | 95% CI | a.coef. | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | |

| Family treatment | ||||||||||

| Peace | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Pressure | −2.4 | −4.4,−0.3 | 0.9 | 0.1,1.7 | 0.82 | 0.53,1.28 | 0.83 | 0.56,1.21 | 1.07 | 0.78,1.48 |

| Aggressive | −1.8 | −4.2,0.7 | 0.7 | −0.1,1.5 | 1.74 | 1.12,2.70 | 0.99 | 0.63,1.55 | 1.35 | 0.94,1.93 |

| Aggressive–severe | −3.4 | −7.3,0.6 | 1.9 | 0.4,3.4 | 3.77 | 2.16,6.57 | 0.63 | 0.29,1.36 | 0.69 | 0.37,1.29 |

| Aggressive–extreme | −5.3 | −10.5,−0.1 | 2.4 | 0.9,3.8 | 1.86 | 1.02,3.43 | 1.64 | 0.87,3.12 | 2.25 | 1.29,3.90 |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 26 or older | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| 18–20 | −2.6 | −4.7,−0.5 | 1.4 | 0.7,2.2 | 0.97 | 0.64,1.49 | 0.63 | 0.43,0.93 | 0.70 | 0.51,0.98 |

| 21–25 | −4.1 | −6.1,−2.0 | 1.6 | 0.9,2.3 | 1.46 | 0.98,2.19 | 1.00 | 0.70,1.42 | 0.94 | 0.69,1.29 |

| Sexual identity | ||||||||||

| Lesbian | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Bisexual | −1.2 | −3.0,0.5 | 0.9 | 0.3,1.5 | 0.67 | 0.48,0.93 | 0.68 | 0.49,0.93 | 1.14 | 0.88,1.48 |

| Unsure | −4.2 | −6.4,−2.0 | 0.8 | 0.1,1.6 | 0.83 | 0.56,1.23 | 0.37 | 0.23,0.59 | 1.04 | 0.75,1.43 |

| Religion | ||||||||||

| No religion | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Any religion | −0.1 | −1.7,1.4 | 0.1 | −0.4,0.6 | 1.21 | 0.91,1.62 | 1.29 | 0.96,1.72 | 1.59 | 1.25,2.01 |

| Family economic status | ||||||||||

| Rich | 7.6 | 3.0,12.1 | −0.3 | −2.2,1.5 | 2.11 | 1.14,3.89 | 1.60 | 0.82,3.15 | 1.20 | 0.66,2.19 |

| Comfortable living | 5.7 | 4.0,7.3 | −0.7 | −1.3,−0.1 | 0.75 | 0.53,1.05 | 0.97 | 0.71,1.33 | 1.01 | 0.78,1.31 |

| Sufficient living | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Poor | −17.6 | −14.0,−10.4 | 3.5 | 2.1,4.8 | 1.17 | 0.66,2.06 | 1.71 | 1.01,2.91 | 1.30 | 0.83,2.04 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||||||

| Not with family | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| With family | −2.1 | −4.0,−0.2 | 0.7 | −0.00,1.4 | 0.97 | 0.69,1.38 | 0.92 | 0.65,1.29 | 0.63 | 0.48,0.84 |

| Urban residence | ||||||||||

| Outside major cities | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| In major cities | 0.2 | −2.1,2.5 | 0.3 | −0.5,1.1 | 1.01 | 0.68,1.51 | 1.06 | 0.71,1.59 | 0.87 | 0.63,1.20 |

| Region | ||||||||||

| Red river delta | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Northern mountains | −4.2 | −9.7,1.3 | 1.0 | −0.9,2.9 | 1.52 | 0.48,4.84 | 0.52 | 0.14,1.97 | 2.87 | 1.16,7.13 |

| Central region | −4.4 | −8.1,−0.7 | 1.6 | 0.2,2.9 | 1.28 | 0.68,2.38 | 0.76 | 0.42,1.40 | 2.36 | 1.38,4.05 |

| South-east region | 0.5 | −1.7,2.6 | 0.5 | −0.3,1.3 | 0.74 | 0.49,1.12 | 0.70 | 0.47,1.02 | 1.64 | 1.13,2.37 |

| Mekong delta | −0.3 | −3.4,2.8 | 1.3 | 0.2,2.4 | 0.77 | 0.43,1.38 | 0.44 | 0.24,0.81 | 3.26 | 2.03,5.24 |

| Lost close friend | ||||||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | −2.8 | −5.2,−0.4 | 2.3 | 1.4,3.3 | 0.96 | 0.64,1.44 | 0.70 | 0.43,1.13 | 0.69 | 0.48,0.98 |

| Discrimination | ||||||||||

| per 1 unit | −1.4 | −2.1,−0.7 | 0.4 | 0.2,0.6 | 1.23 | 1.11,1.35 | 1.22 | 1.11,1.35 | 1.13 | 1.04,1.24 |

All regression coefficients and ORs are adjusted for other predictors (n = 1936). Effects in bold face are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

a.coef., adjusted coefficient; aOR, adjusted odds ratio, which is the adjusted coefficient exponentiated; CI, confidence interval.

FIG. 2.

Family treatment's associations with outcome variables: Adjusted differences in means and adjusted odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) comparing four negative family treatment classes with the peace class (n = 1936). Estimates in solid shapes are statistically significant (P value <0.05); those in hollow shapes are non-significant. All models adjusted for age, sexual identity, religion, family economic status, urban residence, geographical region, discrimination outside the home, and loss of a close friend due to sexual prejudice.

Relative to the peace class, the pressure and aggressive–extreme classes were statistically significantly associated with lower life satisfaction (mean difference point estimates = −2.4 and −5.3, respectively); and the pressure, aggressive–severe, and aggressive–extreme classes were statistically significantly associated with higher depressive symptoms (mean difference point estimates = 0.9, 1.9, and 2.4, respectively)—see CIs in Table 2. An unexpected finding is that respondents in the aggressive class did not fare worse than the pressure class.

Respondents in the aggressive, aggressive–severe, and aggressive–extreme classes had higher odds of suicide attempts than those in the peace class (ORs = 1.74, 3.77, and 1.86, respectively—see CIs in Table 2). These ORs are cumulative ORs, interpreted as both (1) ORs of having ever, versus never, attempted suicide and (2) ORs of having made more-than-one versus zero-to-one suicide attempts. Unexpectedly, the odds of suicide attempts was noticeably higher in the aggressive–severe class than in the aggressive–extreme class, although with the small sizes of these two classes this contrast was not statistically significant (P = 0.057).

The aggressive–extreme class was the only class with statistically significantly higher odds of heavy drinking (OR = 2.25) compared with the peace class. The same class had an OR (1.64) that was statistically non-significant (P = 0.13) but greater than 1 for smoking.

The models presented did not adjust for education due to concern that education might be a mediator, that is, negative family treatment could have resulted in the respondent achieving a lower education level, which could have negatively affected the outcomes. As education is often considered a confounder in health research, we conducted a sensitivity analysis adjusting for education; this did not change the significance or direction of the main study findings.

Discussion

In this study, regression results were consistent with the hypothesis that negative family treatment due to disapproval of same-sex sexuality is predictive of lower well-being and higher suicidality and alcohol use among Vietnamese SMW. Overall, worse outcomes were associated with more negative family treatment subtypes, with SMW who experienced the aggressive–extreme or aggressive–severe types being the worst off across the different outcomes, and those who experienced the aggressive type also having elevated odds of suicide attempts. This supports the relevance of the minority stress model in this Asian sexual minority population, and it adds to the international evidence base on the link between family rejection and poor health and well-being. These findings suggest that services that provide support either to Vietnamese families who are struggling with sexual minority issues or that directly support SMW who experience negative family treatment may help to offset some of the negative consequences identified earlier.

An unexpected finding was that respondents in the aggressive family treatment class did not fare worse than those in the pressure class with respect to current depressive symptoms and life satisfaction. This was surprising given that the aggressive class represented worse family treatment than the pressure class, and the odds of having attempted suicide for SMW in this class were also higher. Since for this population family non-acceptance on finding out about same-sex relationships was common,9 a potential explanation is differential expectation of future family behavior. Some SMW in the pressure class might have experienced few negative family behaviors, because their same-sex sexuality was not yet open knowledge in their families; as such, they might expect to encounter more negative family behavior when additional family members find out. SMW in the aggressive class may have experienced more negative family treatment, because their families were already more aware of their relationships, and, as such, some might not expect worse family treatment in the future. Expectation of rejection is another minority stress component,1 and one study has found that relative to the actual experience of negative social reactions to homosexuality, anticipation of such reactions was a stronger predictor of poorer psychological adjustment.31 Future research examining negative family treatment should incorporate both experience and expectation of negative treatment.

Another unexpected finding was that the second most negative family treatment class (aggressive–severe), and not the most negative class (aggressive–extreme), had the highest odds of suicide attempt. This raises the question of whether there was a healthy-participant bias,32 that is, there may be a more monotone relationship (i.e., more negative treatment is associated with consistently increasing suicide attempt odds) in the SMW population, but the SMW who participated in the survey might have been among the happier ones—more robust, more healthy, and/or less disadvantaged in matters other than family rejection—thus confounding the association between family treatment and the outcome. Since the variable being considered deals with suicide attempts, this raises a question about survivor bias32 in the literal sense (i.e., whether the suicide attempts of SMW with aggressive–extreme family treatment were more serious on average and thus more likely to be completed), as SMW who had already ended their lives had zero probability of participating in the survey. It is important to explore whether this pattern exists in other sexual minority samples, and whether survivor bias is an issue with the most disadvantaged segments of sexual minority populations.

Only the aggressive–extreme class, but not the other negative classes, had elevated odds of heavy drinking compared with the peace class. We can only speculate on why this is the case. Although there are factors that likely contribute to higher drinking among Vietnamese SMW (e.g., minority stress, heavy drinking as transgression of gender rules, and accepting social norms among SMW), there are also family and general society's disapproval of such behavior in women, which may prevent some SMW from heavy drinking. The effect of this disapproval, however, depends on how important these opinions are to the individual. One possibility is that the aggressive–extreme type of family treatment might cause substantial family alienation, leading the SMW to care less about how her family (or neighbors or family friends) judges her behavior—their judgment of her is poor regardless of her behavior. An alternative explanation is that a woman who drank heavily, especially if she was not discreet in doing so, was more likely to face the harshest family treatment, because the drinking behavior was a reminder to the family of her socially deviant status, and because it brought shame to the family when known to others.

Given similar social disapproval for female smoking (as for heavy drinking), it is interesting that we did not find a statistically significant association between family treatment class and smoking. It is noteworthy, however, that the (non-significant) OR for the aggressive–extreme class, again, was the highest. There are potentially two explanations for this, either the influence that family treatment of the aggressive–extreme type had on smoking was truly weaker than its influence on heavy drinking behavior, or we could not detect a significant effect due to lack of power; the lower prevalence of smoking (17.4%) compared with heavy drinking (30%) indicates differential power for these two outcomes.

Although outcome prevalence estimation is not a focus of this study, it is noteworthy that this sample of SMW had considerable health concerns. Seventeen percent were current smokers, a prevalence much higher than the 1.4% in general Vietnamese women, and equivalent to about one third of the 47.4% in general Vietnamese men.33 Suicide attempts were reported by about 17% of study respondents, much more common than in a national Vietnamese youth survey, where the average prevalence was 0.5% and the highest subgroup (urban men aged 18–21) prevalence was 6.4%.34

The study has several limitations. The sample was predominantly young, urban, and on average relatively highly educated, and by study design, all respondents used the internet. These findings are, thus, less generalizable to SMW who are older, live in small towns and rural areas, have little education, and do not use the internet. The cross-sectional nature of the data should also be noted. The predictor-outcome temporal order is not likely an issue for life satisfaction, depressive symptoms, smoking, and heavy drinking, since these outcome variables dealt with the present, whereas the predictor variable (family treatment) was about lifetime experience. The assumed temporal order for the suicide attempt variable could be violated, however, as a person may have attempted suicide before experiencing negative family treatment. Another limitation of the study is that it did not include a covariate representing the degree to which the respondent is open about, or conceals, her sexual minority status; this could be a confounder, because disclosure may increase exposure to negative family treatment and concealment may adversely affect one's health and well-being.

Conclusion

This study found evidence consistent with the minority stress hypothesis that negative family treatment is harmful to mental well-being and contributes to suicidality and alcohol use. It also identified subgroups bearing the greatest burden of the poor outcomes. This calls for special public health attention to this population, and effort to be made in intervening with families to increase tolerance and to prevent maltreatment by family members, as well as in providing support to sexual minority people in coping with family negativity. The study also showed how latent class methods are useful in studying the relationship between a range of negative family treatment experience and health and well-being.

Acknowledgments

Instrument development and data collection were funded by the Institute for Studies of Society, Economy and Environment (iSEE, from core funding) and the Department of Health, Behavior and Society, JHSPH (through doctoral research grants for T.Q.N.). T.Q.N.’s work was supported by the Sommer Scholars Program and the Drug Dependence Epidemiology Training Program (NIDA grant T-32DA007292, PI C. Debra M. Furr-Holden). The authors are grateful for the contribution of survey respondents, the collaboration by websites for Vietnamese SMW, effective implementation support by iSEE and the ICS Center, and helpful inputs from Lê Nguyễn Thu Thủy, Nguyễn Hải Y n, Lê Ki

n, Lê Ki u Châu Loan, Brian Weir, Anna Flynn, Nguyễn Phu'o'ng Qu

u Châu Loan, Brian Weir, Anna Flynn, Nguyễn Phu'o'ng Qu nh Trang, the two anonymous reviewers, and the Chief, Associate, and Managing Editors.

nh Trang, the two anonymous reviewers, and the Chief, Associate, and Managing Editors.

Disclaimer

Preliminary results of these analyses were presented to several Vietnamese groups/organizations and researchers working on LGBT and sexual health and rights at the Workshop on Sexual Discrimination and LGBT Mental Health on June 24, 2014 in Ha Noi, Viet Nam.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Survey respondents included transmen for two reasons: (1) in Viet Nam, transmen tend to mingle socially with SMW, offline and online, and one of the websites used stated explicitly that it served both SMW and transmen; and (2) the Vietnamese word “nũ” (woman) in the screening statement refers to a person being a woman, but it could also be interpreted to refer to the female biological sex. The survey questionnaire asked respondents about gender identity, with the option “I consider myself a man/transguy (even though I was born female),” identifying that a respondent was a transman and not an SMW.

These results are consistent with the prior analysis of the SMW and transmen combined sample, which extracted six classes, including five similar to these five classes plus an additional class that was more common among transmen.10

References

- 1.Meyer IH: Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, et al. : A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, et al. : Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. J Adolesc Health 2011;49:115–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuang M-F, Nojima K: Mental health and sexual orientation of female in Taiwan: Using internet as the research tool. Kyushu Univ Psychol Res 2003;4:295–305 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuang M-F, Nojima K: The mental health and sexual orientation of females: A comparative study of Japan and Taiwan. Kyushu Univ Psychol Res 2005;6:141–148 [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Griensven F, Kilmarx PH, Jeeyapant S, et al. : The prevalence of bisexual and homosexual orientation and related health risks among adolescents in northern Thailand. Arch Sex Behav 2004;33:137–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lam TH, Stewart SM, Leung GM, et al. : Depressive symptoms among Hong Kong adolescents: Relation to atypical sexual feelings and behaviors, gender dissatisfaction, pubertal timing, and family and peer relationships. Arch Sex Behav 2004;33:487–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hidaka Y, Operario D, Takenaka M, et al. : Attempted suicide and associated risk factors among youth in urban Japan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2008;43:752–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

9.Nguyen TQ, Nguyen NTT, Le TNT, Le BQ: S

ng trong một xã hội dị tính: Câu chuyện từ 40 người nữ yêu nữ: Quan hệ với cha mẹ [Living in a heterosexual society: Stories from 40 women who love women: Relationships with parents]. Ha Noi, Viet Nam: Institute for Studies of Society, Economy and Environment; 2010. Available at www.isee.org.vn/Content/Home/Library/lgbt/song-trong-mot-xa-hoi-di-tinh-cau-chuyen-tu-40-nguoi-nu-yeu-nu-quan-he-voi-cha-me.pdf Accessed September2, 2015

ng trong một xã hội dị tính: Câu chuyện từ 40 người nữ yêu nữ: Quan hệ với cha mẹ [Living in a heterosexual society: Stories from 40 women who love women: Relationships with parents]. Ha Noi, Viet Nam: Institute for Studies of Society, Economy and Environment; 2010. Available at www.isee.org.vn/Content/Home/Library/lgbt/song-trong-mot-xa-hoi-di-tinh-cau-chuyen-tu-40-nguoi-nu-yeu-nu-quan-he-voi-cha-me.pdf Accessed September2, 2015

- 10.Nguyen TQ, Bandeen-Roche K, Masyn KE, et al. : Negative family treatment of sexual minority women and transmen in Vietnam: Latent classes and their predictors. J GLBT Fam Stud 2015;11:205–228 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer IH: Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav 1995;36:38–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puckett JA, Woodward EN, Mereish EH, Pantalone DW: Parental rejection following sexual orientation disclosure: Impact on internalized homophobia, social support, and mental health. LGBT Health 2015;2:265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan C, Huebner DM, Diaz RM, Sanchez J: Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics 2009;123:346–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Augelli AR: Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2002;7:433–456 [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW: Suicidality patterns and sexual orientation-related factors among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2001;31:250–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J: Disclosure of sexual orientation and subsequent substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Critical role of disclosure reactions. Psychol Addict Behav 2009;23:175–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Padilla YC, Crisp C, Rew DL: Parental acceptance and illegal drug use among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: Results from a national survey. Soc Work 2010;55:265–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D'Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT: Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. J Interpers Violence 2006;21:1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Salter NP, et al. : Predicting the suicide attempts of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2005;35:646–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams L, Guest MP: Attitudes toward marriage among the urban middle-class in Vietnam, Thailand, and the Philippines. J Comp Fam Stud 2005;36:163–186 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen TQ, Bandeen-Roche K, Bass JK, et al. : A tool for sexual minority mental health research: The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a depressive symptom severity measure for sexual minority women in Viet Nam. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health 2016;20:173–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB: Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. JAMA 1999;282:1737–1744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen TQ: Negative Family Treatment's Effects on the Well-Being of Sexual Minority Women and Transmen in Viet Nam, and the Roles of Sexuality-Related Social Support and Social Connection. 2014. [Doctoral Dissertation], Johns Hopkins University; Available at https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/37830/NGUYEN-DISSERTATION-2014.pdf Accessed January26, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 24.The International Wellbeing Group: Personal Wellbeing Index–Adult (PWI-A) Manual 2006, 4th ed. Melbourne: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masyn KE: Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. In: The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods in Psychology. Edited by Little TD. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp 551–611 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vermunt JK: Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Polit Anal 2010;18:450–469 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakk Z, Tekle FB, Vermunt JK: Estimating the association between latent class membership and external variables using bias-adjusted three-step approaches. Sociol Methodol 2013;43:272–311 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asparouhov T, Muthén BO: Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: 3-step approaches using Mplus. Mplus Web Notes. 2013. Available at: www.statmodel.com/examples/webnotes/webnote15.pdf Accessed June18, 2015

- 29.Muthén LK, Muthén BO: Mplus User's Guide, 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Little TD, Jorgensen TD, Lang KM, Moore EW: On the joys of missing data. J Pediatr Psychol 2013;39:151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross MW: Actual and anticipated societal reaction to homosexuality and adjustment in two societies. J Sex Res 1985;21:40–55 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL: Modern Epidemiology, 3rd ed. Phildadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 33.GATS Viet Nam Working Group, Partner Contributors: Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Viet Nam 2010. Ha Noi, Viet Nam, 2010. Available at www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/en_tfi_gats_vietnam_report.pdf Accessed June28, 2015

- 34.Vuong DA, Van Ginneken E, Morris J, et al. : Mental health in Vietnam: Burden of disease and availability of services. Asian J Psychiatr 2011;4:65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]