Abstract

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are a pressing public health issue due to limited therapeutic options to treat such infections. CREs have been predominantly isolated from humans and environmental samples and they are rarely reported among companion animals. In this study we report on the isolation and plasmid characterization of carbapenemase (IMP-4) producing Salmonella enterica Typhimurium from a companion animal. Carbapenemase-producing S. enterica Typhimurium carrying blaIMP-4 was identified from a systemically unwell (index) cat and three additional cats at an animal shelter. All isolates were identical and belonged to ST19. Genome sequencing revealed the acquisition of a multidrug-resistant IncHI2 plasmid (pIMP4-SEM1) that encoded resistance to nine antimicrobial classes including carbapenems and carried the blaIMP-4-qacG-aacA4-catB3 cassette array. The plasmid also encoded resistance to arsenic (MIC-150 mM). Comparative analysis revealed that the plasmid pIMP4-SEM1 showed greatest similarity to two blaIMP-8 carrying IncHI2 plasmids from Enterobacter spp. isolated from humans in China. This is the first report of CRE carrying a blaIMP-4 gene causing a clinical infection in a companion animal, with presumed nosocomial spread. This study illustrates the broader community risk entailed in escalating CRE transmission within a zoonotic species such as Salmonella, and in a cycle that encompasses humans, animals and the environment.

Clinical infections attributed to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are a pressing public health issue due to limited therapeutic options. In recent years, studies have reported the emergence and global dissemination of CRE and their public health impact1,2. The major globally disseminated carbapenemases include KPC, NDM-1, OXA, IMP and VIM1,2,3. Thus far, CRE have been predominantly isolated from humans and environmental samples1,2,3,4,5. Recent studies have highlighted the global emergence of CREs in both livestock6,7 and companion animals8,9,10. In particular, recent studies demonstrating the isolation of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli (NDM-1 and OXA-48) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (OXA-48) from clinical infections in dogs8,9 and have raised concerns about the veterinary use of carbapenems11.

In Australia, IMP-4 is the most common carbapenemase detected in Gram-negative bacteria. Thus far in Australia, IMP-4 producing Gram-negative bacteria have been reported predominantly in hospital settings, from both clinical and environmental sources5,12,13,14,15,16,17. The blaIMP-4 gene is considered endemic to Australia and is often carried in a blaIMP-4-qacG-aacA4-catB3 cassette array13,14,15,16,17. This blaIMP-4 cassette array is generally found on IncA/C or IncL/M plasmids in New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria13,14, and IncHI2 or IncL/M plasmids in Queensland16,17.

A recent study has identified blaIMP-4 in a range of bacterial species, primarily E. coli, from a single, large, off-shore seagull colony in NSW, Australia18. This study also identified the blaIMP-4-qacG-aacA4-catB3 cassette array among these isolates, where it was associated with IncHI2, IncA/C, IncL/M or IncI1 replicons. Although numerous serotypes of Salmonella enterica were detected in this seagull group, none carried blaIMP-4. Thus far, there has been no prior report of CREs in either livestock or companion animals in Australia.

In this study we report the first isolation of carbapenemase (IMP-4) producing S. enterica from a systemically unwell cat and three additional cats in the same facility. We have also performed for the first time a complete characterization of an IncHI2 plasmid that carries a blaIMP-4-qacG-aacA4-catB3 cassette array and evaluated the heavy metal resistance associated with this plasmid.

Results

Bacterial isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Faecal culturing for Salmonella from the index cat resulted in a heavy, pure growth of S. enterica serotype Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) on XLD agar. The isolate (SA-2) was resistant to a range of antimicrobials including ampicillin, clavulanic-acid potentiated amoxicillin, clavulanic-acid potentiated ticarcillin, cefazolin, cefoxitin, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, meropenem, trimethoprim and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and tested positive for the blaIMP-4 gene. The isolate demonstrated intermediate resistance to tazocin (64 mg/L) and tobramycin (8 mg/L) and was susceptible to ciprofloxacin (S; 1 mg/L), norfloxacin (S; 2 mg/L), cefepime (S; 2 mg/L), amikacin (S; <2 mg/L) and nitrofurantoin (S; 32 mg/L). Of the eight cats tested subsequent to the index case, S. Typhimurium was isolated from an additional three cats.

All the isolates (SA-3, 5, 8) had identical resistance profiles to the S. Typhimurium isolated from the index cat (SA-2) and were positive for the blaIMP-4 gene. Of these three cats: one had contact with the index case, but remained asymptomatic, another was a kitten that was positive for Salmonella spp. before the index case developed diarrhoea. It was located in the same room, but in a separate cage to the index case and had no direct contact. The third case was a young cat which developed diarrhoea, but had no contact with the index case and was not kept in the same room. Following euthanasia of the index case, infection control practices at the cat shelter were reviewed with suggestions to reduce potential cross-transmission. Follow-up monitoring demonstrated absence of Salmonella carriage in all animals tested.

Phylogenetic Analysis

All the isolates (SA-2, 3, 5, 8) belonged to Salmonella enterica sequence type 19 (ST19). The phylogenetic analysis of the core genome revealed that the S. Typhimurium isolates identified in this study were closely related to internationally reported S. Typhimurium ST19 isolates and the S. Typhimurium ST19 reference strain (ATCC 14028s) isolated from poultry in the US. Whole genome sequence data revealed that all four isolates belong to sequence type 19 (ST19). At the pan genome level, the four S. Typhimurium isolates from this study and the reference ST19 S. Typhimurium (ATCC 14028s) strain shared 4879 common genes. The SNP analysis using 4879 common genes demonstrated that all the isolates were identical with the exception of SA-5 which had 2 additional SNPs. All the isolates had 17 SNP differences compared to the reference strain with the exception of SA-5 (19 SNPs).

Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

Whole genome sequence data revealed the presence of the following antimicrobial resistance genes in the S. Typhimurium isolates: β-lactams (blaTEM-1B, blaOXA-1), metallo-β-lactams (blaIMP-4), aminoglycosides (aac(6′)Ib-cr, aacA4, strB, strA, aac(3)-IId), fluoroquinolones (aac(6′)Ib-cr, qnrB2), macrolides [mph(A)], trimethoprim (dfrA19), sulphonamides (sul1), chloramphenicol (catA2, catB3) and tetracycline (tetD).

Plasmid Characterization

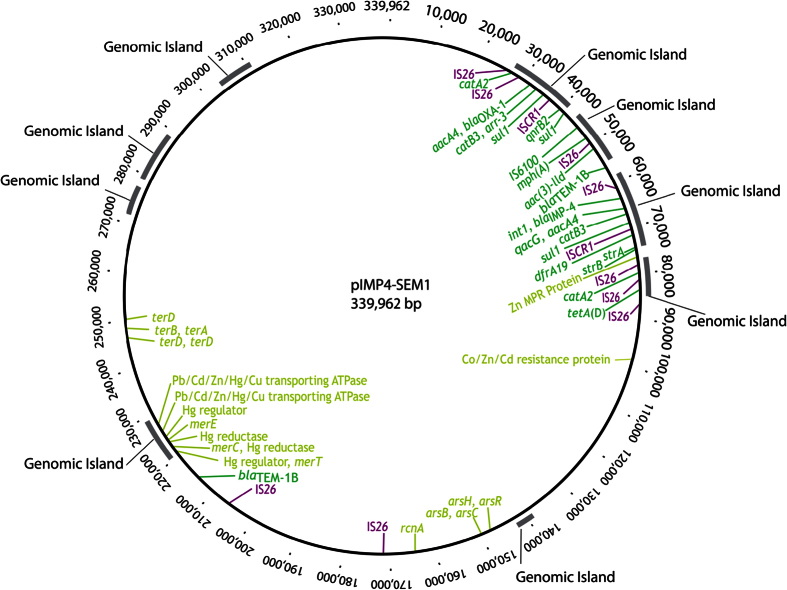

PacBio sequencing revealed two plasmids; the first a common virulence-associated plasmid, and the second a resistance-associated plasmid. The resistance plasmid (pIMP4-SEM1; GenBank accession number KX810825) was an IncHI2 plasmid (339 kb) that carried all of the antimicrobial resistance genes identified from whole genome sequence analysis (Fig. 1). Conjugation experiments revealed that the carbapenemase-encoding encoding IncHI2 plasmid was easily transferred to E. coli J53 with an efficiency of 1.36 × 10−2 on MacConkey agar supplemented with ampicillin.

Figure 1. Genomic map of pIMP4-SEM1 carried by carbapenemase-producing Salmonella enterica Typhimurium.

Significant antimicrobial and heavy-metal resistance associated genes are indicated in green and yellow colours, respectively. Predicted genomic islands are indicated in grey, and insertion sequence positions are indicated in purple.

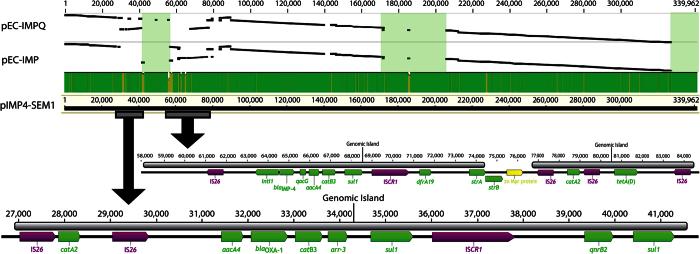

The resistance plasmid carried a blaIMP-4-qacG-aacA4-catB3 cassette array and an aacA4-blaOXA-1-catB3-arr3 cassette array (Figs 1 and 2). In addition to this, the resistance plasmid (pIMP4-SEM1) also contained a number of other antimicrobial resistance genes. Figure 1 shows the arrangement of antimicrobial resistance genes, transposons (IS26), integrons (int1) and insertion sequence common region (ISCR1) among the multidrug resistance region harboured in the cassette arrays on the pIMP4-SEM1 plasmid.

Figure 2. Arrangement of multidrug-resistant regions on pIMP4-SEM1 and genome comparison to pEC-IMP and pEC-IMPQ.

Dotplots indicate the percentage identity between pEC-IMPQ and pIMP4-SEM1 and pEC-IMP and pIMP4-SEM1, with increasing plot angles demonstrating homology on the same strand and decreasing plot angles demonstrating homology on opposite strands. Regions showing significant gaps between pEC-IMPQ/pEC-IMP and pIMP4-SEM1 and are indicated by light green boxes. Regions of pIMP4-SEM1 containing the blaIMP-4-qacG-aacA4-catB3 cassette array and the aacA4- blaOXA-1-catB3-arr3 cassette array are shown as grey rectangles in the respective positions on the linear genome, with expanded views below.

The resistance plasmid was most similar to the IncHI2 plasmids from Enterobacter spp. from China, pEC-IMP and pEC-IMPQ (GenBank accession numbers EU855787 and EU855788 respectively) that harboured blaIMP-8. Blastn analysis of pIMP4-SEM1 against both plasmids revealed a query coverage of 85% and an identity of 99%19. Most of the antimicrobial resistance genes were conserved between the three plasmids (Fig. 2). Analysis of the main regions of difference, spanning positions 40,000 to 56,000 of the pIMP4-SEM1 plasmid, revealed a small number of antibiotic resistance genes of low public health significance were present in pIMP4-SEM1 including mph(A), aac(3)-lld and blaTEM-1B, but not in pEC-IMP or pEC-IMPQ. The second region, spanning positions 172,000 to 205,000, did not reveal any genes associated with antimicrobial resistance or gene transfer. Both pIMP4-SEM1 and pEC-IMP/pEC-IMPQ plasmids were notable for the presence of a wide range of heavy metal resistance-associated genes. These include genes associated with resistance to arsenic, copper, cobalt, zinc, cadmium, lead and mercury. The majority of these genes were harboured in positions 149,372–166,783 and 221,513–250,546 (Figs 1 and 2). The most significant heavy metal resistance operon was an arsenic resistance operon containing the genes arsB, arsC arsH and arsR. All heavy metal resistance-associated genes were identified in all three plasmids.

The virulence plasmid (pSTV-MU1) (GenBank accession number KX777254) was 93,807 bp in size and carried multiple Salmonella virulence factor genes including the Salmonella plasmid virulence (spv) locus (spvABCDR) and the plasmid encoded fimbriae (pef ) locus (pefABCDI), along with an extensive array of IncF-associated genes. There were no antimicrobial resistance or heavy metal resistance-associated genes present on this plasmid. This plasmid showed 99% identity with query coverages ranging from 97–100% to 26 Salmonella virulence plasmids deposited in GenBank.

Heavy Metal Susceptibility

Heavy metal susceptibility to arsenic, copper, cobalt and zinc was performed to evaluate phenotypic resistance to heavy metals (Table 1). All S. Typhimurium isolates and the two transconjugants of E. coli J53AzR (SA77, 78) that carried the resistance plasmid were non-susceptible to arsenic with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 150 mM. By comparison, the control strains E. coli ATCC 25922 and J53AzR were susceptible to arsenic at 3.5 mM and 15 mM, respectively. All the tested isolates were susceptible to cobalt, zinc and copper (Table 1).

Table 1. Heavy metal susceptibility of Salmonella enterica Typhimurium isolates from cats and the two transconjugants of E. coli J53AzR that carried the resistance plasmid.

| Isolate ID | MIC (mM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium arsenate | Copper sulphate | Cobalt chloride | Zinc sulphate | |

| SA2 | 150 | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| SA3 | 150 | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| SA5 | 150 | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| SA8 | 150 | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| SA77* | 150 | 3 | 6 | 1.5 |

| SA78* | 150 | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| E. coli J53AzR | 15 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| ATCC 25922 | 3.5 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

*Transconjugants of E. coli J53AzR that carried the resistance plasmid.

Discussion

In this study we report the first case of clinical infection and carriage of CREs in Australian companion animals and the first detection of blaIMP-4 positive Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium from Australia. This study also reports on the genomic characteristics of an IncHI2 plasmid from Australia that carries the blaIMP-4-qacG-aacA4-catB3 cassette array, with demonstrated co-carriage of heavy metal resistance (arsenic).

This is the first report of carbapenem resistance and, more importantly, the presence of a transmissible carbapenemase gene (blaIMP-4) in a zoonotic species such as S. Typhimurium. To date, Australian S. enterica strains from livestock remain susceptible to a majority of antimicrobial classes20,21,22 and there have been no reports of CRE among companion animals or livestock in Australia23,24. However, studies have reported blaIMP-4 positive CRE among humans, seagulls and in hospital environments, with the predominant bacteria identified as E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., and some environmental bacterial genera5,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Detection of this extensively drug-resistant S. Typhimurium isolate among cats is a significant finding from both an animal health and public health perspective due to the potential for the transfer of these bacteria to other animals and to humans. The acquisition of carbapenem resistance in S. enterica is unlikely due to selection pressure from carbapenem use in companion animals since there was no history of such use in the shelter and carbapenems are very rarely used to treat companion animals in Australia11. However, co-selection of carbapenem resistance by the use of registered veterinary drug classes (e.g. β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, tetracylines) may play a role in the acquisition of HI2 like plasmids that carry a wide spectrum of genes encoding resistance to carbapenems and other antimicrobials, including those registered for veterinary use in Australia. With the advent of molecular diagnostics in veterinary pathology, microbiologic diagnoses for enteric infections are increasingly made using PCR based detection methods alone. Without bacterial culture and susceptibility testing of isolates, there is potential for loss of valuable information on emerging critical antimicrobial-resistant pathogens in animals.

Genomic characterization revealed the acquisition of a highly transferable IncHI2 resistance plasmid by a non-host specific, relatively common ST19 clone of S. Typhimurium. Acquisition of this plasmid conferred resistance to nine classes of antimicrobials including the critically important classes such as carbapenems (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the isolate demonstrated reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, possibly mediated by two plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes (qnrB2 and aac(6)-Ib-cr), conferring reduced susceptibility to some members of this class and greater propensity to develop mutations in the QRDRs of target chromosomal genes under fluoroquinolone selection pressure.

Recent studies have demonstrated that a highly transferable conjugative IncHI2 plasmid encoding blaIMP-4 were responsible for increased reports of CRE in Queensland, Australia16,17. However, limited information is available on the genomic characteristics of IncH12 plasmids that carry blaIMP-4. The comparative genomic characterisation undertaken in this study revealed that the S. Typhimurium IncHI2 plasmid was closely related to IncHI2 plasmids that carry blaIMP-8 identified from clinical Enterobacter spp. isolates in China. Although there are some deletions in the IncHI2 plasmids from China, the significant majority of the antimicrobial resistance and heavy metal resistance-associated genes identified, including the blaIMP-4-qacG-aacA4-catB3 cassette array, are conserved between the three plasmids analysed from Australia (this study) and China (Fig. 2). Similarly, a recent report demonstrated that blaIMP-4 encoding IncL/M plasmids from Australia shared similar features to several IncL/M plasmids from both Poland and China14. While the origin L/M and HI2 plasmids that carry a large spectrum of antimicrobial resistance genes including carbapenem resistance is unclear, the close similarity in genetic content of this plasmid may indicate inter-continental distribution and spread of this critical antimicrobial drug resistance encoding plasmid.

A recent study of CREs isolated from seagulls in NSW Australia has also confirmed the carriage of both L/M and HI2 plasmids containing the blaIMP-4 cassette array18. This raises the question as to whether these plasmids are circulating within the environment in the absence of any antimicrobial selection pressure. One alternative hypothesis, evidenced by the large number of heavy metal resistance-associated genes identified on the IncHI2 backbone, is that exposure of bacteria to heavy metals in the environment may lead to co-selection of plasmids carrying both heavy metal and antimicrobial resistance genes. Although a large number of heavy metal resistance-associated genes were identified on the resistance plasmid (pIMP4-SEM1, Fig. 1), only the arsenic resistance phenotype was observed by MIC testing. This is an interesting finding and demonstrates that the presence of heavy-metal resistance-associated genes alone on a plasmid may not be sufficient for tolerance but may require other genes or host co-factors. The high arsenic MIC (150 mM) identified among the S. Typhimurium isolates and transconjugates does, however, demonstrate co-evolution and co-selection of resistance to both critically important antimicrobials and heavy metals. Further studies are required to examine this phenomenon among CRE in a One Health context.

This study illustrates the broader community risk entailed in escalating CRE transmission within a zoonotic species such as Salmonella. The findings raise potential concerns for transmission of blaIMP-4-positive Salmonella spp. to humans and the transfer of IncHI2 resistance plasmids to other pathogenic bacterial species such as extra-intestinal pathogenic E. coli that share similar ecological niches between humans, companion animals and the environment. There is increasing detection of CRE in Australian hospitals due to carriage of plasmid-encoded blaIMP-45,12. Therefore, it is important to identify the full extent of spread of these plasmids in the environment and to evaluate the potential impact of CRE carriage within companion animals and other animal species including wildlife.

Although, there was initial nosocomial spread between several animals, infection control practices contained the spread of the resistant S. Typhimurium within the cat facility. An infectious disease physician (EC) and a veterinary specialist (RM) visited the cattery to critique and modify infection control practices. This One Health approach was successful in controlling the local transmission and spread of potentially zoonotic CRE. The carriage of the qacG gene on the IncHI2 plasmid that encodes resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds often used as disinfectants may have infection control implications in veterinary and human clinical settings.

In conclusion, this study for the first time reports on clinical disease due to a blaIMP-4 positive S. enterica in an Australian companion animal and presumed nosocomial spread to other cats in the cat shelter. This study also reveals the full genomic characteristics of a highly transferable IncHI2 plasmid that encodes resistance to carbapenems, range of other classes of antimicrobials and arsenic resistance. Further environmental studies are continuing to examine levels of endemicity of transferable carbapenem resistance in Salmonella spp. and other Enterobacteriaceae.

Methods

Initial Detection and Screening

Following treatment of an upper respiratory tract infection with doxycycline, a three-year-old castrated male domestic shorthair cat in a cat shelter developed severe haemorrhagic diarrhoea accompanied by malaise and reduced appetite. On admission to a veterinary hospital, a faecal specimen was positive for Salmonella spp. by PCR. A rectal swab was therefore sent to the Department of Microbiology Concord Hospital for culture and susceptibility testing. Over the next 48 hours the cat deteriorated rapidly with persistent haemorrhagic diarrhoea and fever, resulting in dehydration and hypovolaemia. A decision was made to euthanase the animal. Rectal swabs were collected from eight cats housed within the same facility, including a cat that had developed mild diarrhoea two weeks after the index case. These cats had been housed in the isolation ward of the shelter when the index cat was symptomatic. Subsequently, rectal swabs were collected from a further nine cats to exclude ongoing Salmonella transmission. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. As samples were for diagnostic purposes, Murdoch University Animal Ethics Committee has issued an Animal Ethics not Required Letter (Protocol number: 270) as per Australian National Health and Medical Research, Animal Research Ethics code.

Salmonella isolation and characterization

Isolation was performed on XLD media (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and typical Salmonella colonies identified by MALDI-TOF (Bruker), VITEK® 2 (bioMérieux) biochemical identification and latex agglutination (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The phenotypic antimicrobial resistance profiling was performed on VITEK® 2 (bioMérieux). Once carbapenem resistance was identified a CarbaNP Test was performed (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by blaIMP gene PCR testing25. The blaIMP-4 characterization was performed using the following in-house PCR-Primers Imp4-F 5′-CACTTGGTTTGTGGAACGTG-3′ Imp4-R 5′-CAATAGTTAACCCCGCCAAA-3′ with a melt peak at 79 to 80.5 °C. Isolates resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobials were classified as multidrug-resistant.

Conjugation experiments

Transferability of the resistance plasmid was performed by bacterial conjugation using E. coli J53AzR, as previously reported26. The selection of the transconjugants were made on MacConkey’s agar containing sodium azide (100 mg/L) and ampicillin (150 mg/L) or gentamicin (10 mg/L) or imipenem (0.2 mg/L).

Whole genome sequencing

Whole genome sequencing was performed on all four S. enterica isolates (SA-2, 3, 5, 8) using Illumina MiSeq Chemistry. Samples underwent library preparation using Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and sequencing was performed on a MiSeq V3 2 × 300 flowcell. Raw sequence reads were assembled de novo using CLC Genomics Workbench v8.5.1. The Nullabor pipeline v1.01 was used to assemble the four Illumina sequenced strains. The reference genome of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028s (accession number CP001363) was used as a reference strain for core genome SNP analysis27.

The index case isolate (SA-2) was also subject to PacBio Sequencing. The sequence data was assembled de novo using PacBio software and the Quiver programme, and annotation was performed using RAST28, with annotation editing performed using Geneious v8.1.2. Pairwise alignment of plasmids was performed using LASTZ29.

Screening for antimicrobial resistance genes, MLST and plasmid replicon type was performed using the tools available from Centre for Genomic Epidemiology (http://www.genomicepidemiology.org/). Genomic islands were predicted using IslandViewer 330.

Screening for heavy metal resistance

Sodium arsenate, copper sulphate, zinc sulphate and cobalt chloride were used to determine the heavy metal susceptibility of S. enterica isolates (SA-2, 3, 5, 8), E. coli J53AzR and two transconjugants of E. coli J53AzR (SA77,78) that carried the resistance plasmid. The metal susceptibility was performed as per Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute Guidelines for performing MIC testing of antimicrobials using Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or agar31. Testing was performed in triplicate in both agar dilution and micro-broth dilution. For agar dilution, metals were suspended in varying concentration in LB agar and 10 μL of 5 × 105 CFU/mL of each strain was spotted in triplicate on the plates, followed by incubated for 22 hours at 37 °C. For micro-broth dilution, metals were diluted at varying concentration in LB broth and 10 μL of 5 × 105 CFU/mL added to each well and incubated for 22 hours at 37 °C. E. coli ATCC 25922 and J53AzR were used as controls.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Abraham, S. et al. Isolation and plasmid characterization of carbapenemase (IMP-4) producing Salmonella enterica Typhimurium from cats. Sci. Rep. 6, 35527; doi: 10.1038/srep35527 (2016).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Glen Carter, Ms. Sarah Baines, Prof. Benjamin Howden from the Doherty Applied Microbial Genomics, The Doherty Institute for Infection & Immunity, University of Melbourne for their assistance in performing PacBio sequencing. We thank Dr. Chris McDevitt for the critical review of the manuscript. We also thank Mr. Terence Lee for technical assistance. This work was supported by Australian Research Council Linkage Grant with Zoetis and Luoda Pharma as the industry partners [grant no. LP130100736] and a small research grant of School of Veterinary and Life Sciences, Murdoch University [grant no. 1152]. RM is supported by the Valentine Charlton Bequest.

Footnotes

SA and DJT have received research grants and contracts from Zoetis, Novartis and Neoculi. All other authors have none to declare.

Author Contributions T.G., D.J.T., R.M. and S.A. conceived the idea and over all supervision of the project; D.H., G.M., E.Y.L.C., J.M. and T.G. collected samples (including repeated sampling) and performed initial phenotypic and genotypic characterisation of Salmonella from index and in-contact cats; E.Y.L.C., R.M. and D.H. advised on infection control and implementation; S.A., D.J.T. and M.O. conceived experimental design after isolation; S.A., M.O. and S.P. performed genome sequencing and analysed genomic data; S.S. and R.J.A. designed and performed trans-conjugation and heavy metal resistance screening. All authors contributed to writing and revising the manuscript.

References

- Kumarasamy K. K. et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis 10, 597–602 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N., Limbago B. M., Patel J. B. & Kallen A. J. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Epidemiology and prevention. Clin Infect Dis 53, 60–67 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann P., Naas T. & Poirel L. Global spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis 17, 1791–1798 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodford N., Wareham D. W., Guerra B. & Teale C. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and non-Enterobacteriaceae from animals and the environment: an emerging public health risk of our own making? J Antimicrob Chemother 69, 287–291 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung G. H., Gray T. J., Cheong E. Y., Haertsch P. & Gottlieb T. Persistence of related blaIMP-4 metallo-β-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae from clinical and environmental specimens within a burns unit in Australia - a six-year retrospective study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2, 1–8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.-J. et al. Complete sequence of the blaNDM-1-carrying plasmid pNDM-AB from Acinetobacter baumannii of food animal origin. J Antimicrob Chemother 68, 1681–1682 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Identification of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase 1 in Acinetobacter lwoffii of food animal origin. PLoS One 7, e37152 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolle I. et al. Emergence of OXA-48 carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in dogs. J Antimicrob Chemother 68, 2802–2808 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen B. W., Nayak R. & Boothe D. M. Emergence of New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase (NDM-1) encoding gene in clinical Escherichia coli isolates recovered from companion animals in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57, 2902–2903 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedel J. et al. Multiresistant extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae from humans, companion animals and horses in central Hesse, Germany. BMC Microbiol 14, 1–13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham S., Wong H. S., Turnidge J., Johnson J. R. & Trott D. J. Carbapenemase-producing bacteria in companion animals: a public health concern on the horizon. J Antimicrob Chemother 69, 1155–1157 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg A. Y., Franklin C., Bell J. M. & Spelman D. W. Dissemination of the metallo-β-lactamase gene blaIMP-4 among Gram-negative pathogens in a clinical setting in Australia. Clin Infect Dis 41, 1549–1556 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espedido B. A., Partridge S. R. & Iredell J. R. blaIMP-4 in different genetic contexts in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from Australia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52, 2984–2987 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge S. R., Ginn A. N., Paulsen I. T. & Iredell J. R. pEl1573 Carrying blaIMP-4, from Sydney, Australia, is closely related to other IncL/M plasmids. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56, 6029–6032 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidjabat H. E., Heney C., George N. M., Nimmo G. R. & Paterson D. L. Interspecies transfer of blaIMP-4 in a patient with prolonged colonization by IMP-4-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol 52, 3816–3818 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidjabat H. E. et al. Dominance of IMP-4-producing Enterobacter cloacae among carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Australia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59, 4059–4066 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidjabat H. E., Robson J. & Paterson D. L. Draft genome sequences of two IMP-4-producing Escherichia coli sequence type 131 isolates in Australia. Genome Announc 3, e00983–00915 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolejska M. et al. High prevalence of Salmonella and IMP-4-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the silver gull on Five Islands, Australia. J Antimicrob Chemother 71, 63–70 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-T. et al. Mobilization of qnrB2 and ISCR1 in plasmids. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53, 1235–1237 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham S. et al. Salmonella enterica isolated from infections in Australian livestock remain susceptible to critical antimicrobials. Int J Antimicrob Agents 43, 126–130 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande V., Gole V., McWhorter A. R., Abraham S. & Chousalkar K. K. Antimicrobial resistance of non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates from egg layer flocks and egg shells. Int J Food Microbiol 16, 23–26 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow R. et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella and Escherichia coli from Australian cattle populations at slaughter. J Food Protection 78, 912–920 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham S. et al. Phylogenetic and molecular insights into the evolution of multidrug-resistant porcine enterotoxigenic E. coli in Australia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 44, 105–111 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham S. et al. First detection of extended-spectrum cephalosporin- and fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli in Australian food-producing animals. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 3, 273–277 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes R. E. et al. Rapid Detection and identification of metallo-β-lactamase-encoding genes by multiplex real-time PCR assay and melt curve analysis. J Clin Microbiol 45, 544–547 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby G. A. & Han P. Detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol 34, 908–911 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvik T., Smillie C., Groisman E. A. & Ochman H. Short-Term signatures of evolutionary change in the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium 14028 genome. J Bacteriol 192, 560–567 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz R. K. et al. The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology. BMC Genomics 9, 75–75 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. S. Improved pairwise alignment of genomic DNA. Ph.D. Thesis, The Pennsylvania State University (2007).

- Dhillon B. K. et al. IslandViewer 3: more flexible, interactive genomic island discovery, visualization and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 43, W104–W108 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated From Animals; Approved Standard—Fourth Edition. VET01-A4. Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2013.