Abstract

Objectives

To analyse the effect of women's characteristics on their willingness to join a blind or a non-blind subtrial or to be excluded by physicians.

Design

Primary prevention trial of postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT). A 2×2, randomised design with a non-blind HT arm or control arm and a blind HT arm or placebo arm.

Setting

3 clinical centres in Estonia.

Methods

Interest in joining the trial was asked in a questionnaire together with demographic and health status data. Interested and eligible women were invited to a health examination that also informed whether they belonged to a blind or to a non-blind subtrial; the arm was not revealed. Trial physicians made further exclusions when checking the women's eligibility. Thereafter, informed consent was asked as detailed in the flow chart. Comparisons were made between non-blind and blind subtrials. Analyses were carried out for each of the background variables.

Outcome measures

The proportion of willingness, eligibility and attendance.

Results

Women randomised to the non-blind subtrial were more willing to join (relative risk (RR) 1.17) and more likely to be found eligible by physicians (RR 1.10) than women in the blind subtrial, resulting in larger attendance (RR 1.29). Women with higher education were differentially more willing to join the non-blind trial (RR 1.29) than those with basic education (RR 1.08); the differential willingness of never-smokers (RR 1.20) was larger than that of current smokers (RR 1.07). The differential exclusion by physicians by education and smoking were small. Some subjective symptoms (eg, diarrhoea/constipation, stomach pain) had reverse differential effects on attendance in the non-blind subtrial in comparison to the blind subtrial. Menopausal symptoms did not affect the differential interest, eligibility or attendance.

Conclusions

Blinding in RCT reduces attendance, due to decisions of the women and the trial physicians. Differential attendance by blinding may affect the generalisability of the results from trials.

Trial registration number

Keywords: STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS, BLINDING, TRIALS, SELECTION BIAS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Two subtrials, blind and non-blind, which were run in parallel, were compared.

The effect of participants' characteristics on recruitment in blind versus non-blind trials has not been studied previously.

It is difficult to separate women's and physicians' decisions.

Only a limited number of characteristics were compared.

Introduction

The Estonian Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy (EPHT) Trial was a primary prevention trial of postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT) carried out in three clinical centres in Estonia from 1999 to 2014. The objective of the EPHT Trial was to assess the effect of HT on the use of health services and on the health of the women. To achieve the first objective, we designed randomisation without blinding, while blinding was an essential dimension in the design of the second objective. Therefore, randomisation was carried out in a 2×2 design, which enabled us to evaluate the effect of blinding itself. Women were randomised into blind and non-blind subtrials, which were disclosed before the ultimate confirmation of willingness and signing of the informed consent. At the final assessment of eligibility, the trial physicians also knew whether the woman belonged to the blind or non-blind subtrial.

Several authors have shown that inadequate allocation concealment or lack of blinding can result in biased estimates of intervention outcomes, especially in trials with subjective outcomes.1 2 Non-blind trials tend to exaggerate the effect size,3 4 but the degree of bias may vary.4 5 So far as we know, studies looking at whether participants in blind and non-blind trials differ by their background characteristics and how the different background characteristics affect recruitment into blind and non-blind trials have never been published before.

We have previously shown6 in a preventive postmenopausal HT trial that the final attendance was about 30% larger in the non-blind arm subtrial than in the blind subtrial. In a previous article,7 we found that both during the trial period and follow-up, more cases of coronary heart disease, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, bone fractures and total deaths were observed in the controls of the non-blind subtrial than in the blind subtrial placebo arm. Disease-specific differences in outcomes were not statistically significant, but taken together the consistency in the differences could not be accounted for by random variation.

In this paper, we compare the effects of background characteristics of women on the difference in willingness to make the recruitment visit and second on the exclusions made by the trial physician during the recruitment visit in the non-blind subtrial compared with the blind subtrial. Finally, the final effect of the same background characteristics when being recruited among all randomised women was compared between the non-blind and blind subtrial.

Methods

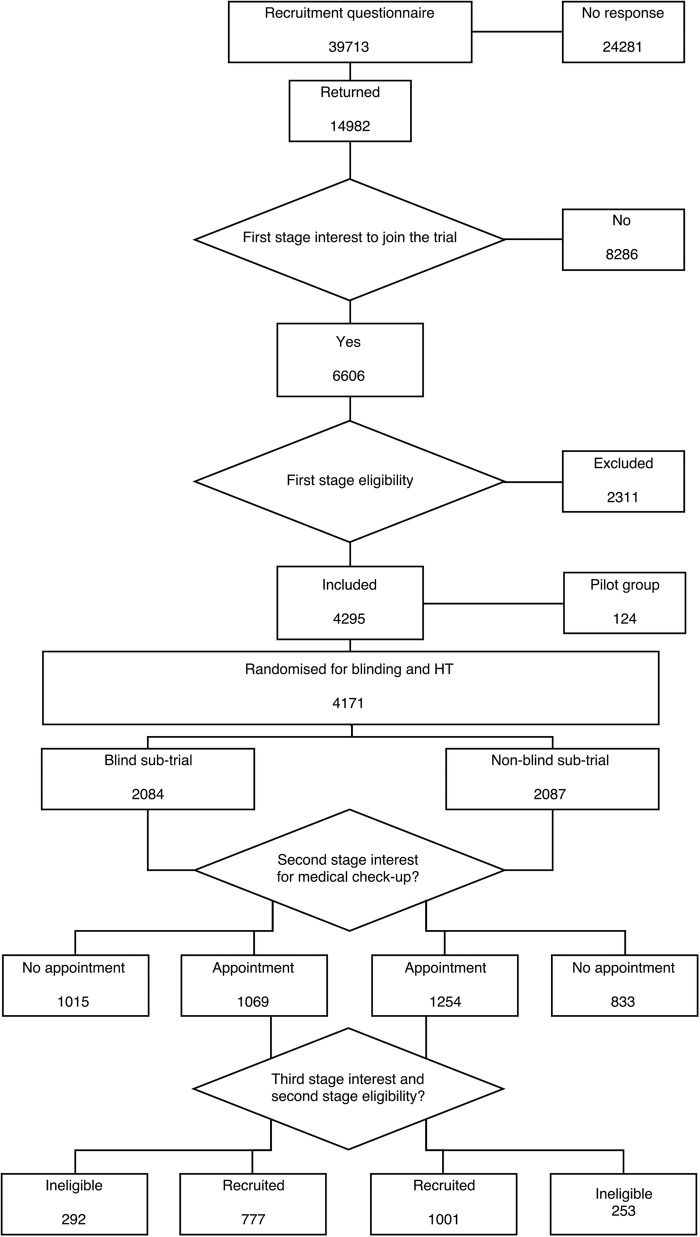

The data were obtained from the recruitment process in the EPHT Trial. This was a randomised trial on the effect of HT on health outcomes,8 use of health services9 and quality of life.10 Recruitment to the trial was conducted by means of a questionnaire sent to all 50–64 years old Estonian-speaking women in two areas, Tallinn and Tartu and their surrounding counties (n=39 713, figure 1) in 1999. Names and addresses were obtained from the population register. A detailed description of the recruitment process has been published elsewhere.11

Figure 1.

Flow chart on randomisation in the EPHT Trial. EPHT, Estonian Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy; HT, hormone therapy.

Attached to the recruitment questionnaire was a two-page leaflet explaining the need for the trial and describing the assumed or known beneficial and harmful effects of postmenopausal HT. The trial design was described in general terms, saying that those interested would be randomly allocated into three groups: HT, placebo and no treatment. The questionnaire asked about women's health, background characteristics and interest in joining the trial (Do you want to participate in a trial on postmenopausal therapy as described in the enclosed leaflet?). Those interested but found to be ineligible on the basis of the questionnaire data were sent a thank you letter stating the reasons for their ineligibility. Figure 1 shows that 14 982 women returned the recruitment questionnaire, and from those 6606 women showed first stage interest in joining the trial according to the returned recruitment questionnaire, with 4295 eligible according to the recruitment questionnaire (first stage eligibility). The randomised 124 pilot group women were not included in the present analysis due to their different background characteristics, leaving 4171 women in the present analyses.

The exclusion criteria in the recruitment questionnaire were as follows: last menstrual period <12 months ago, no valid health insurance, use of HT in past 6 months, myocardial infarction in past 6 months, hepatitis or functional liver disorder in past 3 months, cerebral infarction, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, endometriosis, porphyry ever, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer or meningioma ever and any other form of cancer in the past 5 years.

The interested and potentially eligible women (n=4171) were randomised into four arms (blind subtrial with options of blind HT or placebo and non-blind subtrial, with the options of open-label HT or no treatment arms) by clinic (three clinics). Randomisation was performed from 1999 to 2001 in seven batches, using a computer-based stratified block randomisation program (block size 16). The code of treatment was sealed in a fully opaque envelope.

Each of the 4171 women was sent a personal invitation letter, indicating whether they were in a blind or non-blind subtrial. It advised the woman to phone the study midwife at the clinic to make an appointment for a clinical examination by a trial physician. If the woman invited did not respond, a coordinating study physician invited her by telephone. Starting with the third recruitment batch, if the woman had not been reached by telephone, a reminder letter was sent asking her to make an appointment. Altogether 2323 of the 4171 women arrived for the health check-up (second stage interest in joining the trial). In total, 833 women in the non-blind subtrial and 1015 in the blind arm did not show up at the clinic (see figure 1).

The study physicians (eight altogether) were given detailed instructions on what to ask and measure, and what were the exclusion criteria (in addition to those listed above, untreated hypertension or hypertension resistant to drug therapy, irregular postmenopausal bleeding, abnormal PAP-screen result, menstrual bleeding within the past 12 months, desire for HT, or plans to move out of the area). Determining eligibility required two visits to the clinic, since some examination results were not ready at the first visit.

At the clinic the envelope containing the code for the treatment arm was opened after signing the informed consent form. The envelope contained a drug sheet for the midwife and a one-page leaflet to be given to the woman. This leaflet again explained the study design and the method of taking or not taking the drug, and described potential adverse effects and any symptoms that would necessitate contacting the study physician or an emergency clinic.

In the blind subtrial, women were told that they would remain blind with regard to the HT or placebo arms until the end of the trial. Women in the HT arm of the non-blind subtrial were told that they would be receiving HT. Women in the control arm were told that they would receive no treatment, but they were asked to fill in the annual questionnaires and pay a visit to the trial physician.

The ultimate willingness (third stage interest and second stage eligibility) was confirmed by written consent. The final numbers of women who consented were 494 in the non-blind HT arm, 507 in the non-blind control arm, 404 in the blind HT arm and 373 in the blind placebo arm. All trial participants signed the informed consent form. In the written consent form, all women accepted that they would be additionally followed through registries.

The outcome variables were the proportion of willingness, eligibility and attendance. Willingness was estimated as the proportion of women who paid the recruitment visit (n=2323) among all randomised women (4171; second stage interest). Eligibility was estimated as the proportion of women who ultimately joined the trial (n=1778) among all who paid the recruitment visit (n=2323; third stage interest and second stage eligibility). Attendance was estimated as the proportion of women who finally joined the trial (n=1778) among all randomised women (n=4171).

The analyses were stratified by each of the background variables. Information on different background factors was obtained from the recruitment questionnaires.

As a measure of the differential effect of the background characteristics, the corresponding relative probabilities (abbreviated RR for ‘relative risk’) of any of the outcome variables in the non-blind versus the blind subtrial in each stratum defined by the background characteristics were used. Thus, an RR>1 indicates that blinding makes the trial less ‘attractive’ to women with the characteristic in question. We use the terms relative probabilities, differential (relative) risk, differential outcome (willingness, eligibility, attendance) and differential effect interchangeably. Ninety-five per cent CIs for relative probabilities (RR) were calculated using the standard formula, based on asymptotic normality of logarithmic RR.12

Results

The woman's overall willingness was higher if the woman was in the non-blind subtrial (RR 1.17 non-blind vs blind). There were lesser exclusions in the non-blind arm, resulting in higher overall eligibility (RR 1.10, non-blind vs blind). Thus, the attendance was higher in the non-blind arm than in the blind arm (RR 1.29). All strata-specific outcomes regarding differential willingness, eligibility and attendance can be compared with these reference values (presented also in the tables as totals).

Women with higher education had a higher willingness to join the non-blind subtrial (RR 1.29) than those with secondary education (RR 1.13) or basic education (RR 1.08; table 1). Differential eligibility was quite similar in all educational groups. Therefore, the differential attendance was highest among women with higher education.

Table 1.

Relative probabilities (RR, non-blind vs blind subtrial) of the willingness by woman and of the eligibility by doctor and the ultimate attendance by the woman's socioeconomic status, EPHT Trial

| Socioeconomic status | Willingness (95% CI) | Eligibility (95% CI) | Attendance (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | |||

| Basic | 1.08 (0.91 to 1.27) | 1.14 (0.97 to 1.34) | 1.22 (0.97 to 1.54) |

| Secondary | 1.13 (1.05 to 1.22) | 1.09 (1.03 to 1.16) | 1.24 (1.13 to 1.36) |

| Higher | 1.29 (1.17 to 1.42) | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.18) | 1.42 (1.25 to 1.60) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 1.13 (0.90 to 1.42) | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.20) | 1.11 (0.82 to 1.50) |

| Married | 1.17 (1.10 to 1.26) | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.17) | 1.29 (1.18 to 1.42) |

| Divorced | 1.15 (1.01 to 1.32) | 1.15 (1.02 to 1.29) | 1.33 (1.12 to 1.58) |

| Widow | 1.18 (1.01 to 1.37) | 1.08 (0.96 to 1.22) | 1.27 (1.05 to 1.55) |

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 1.20 (1.13 to 1.28) | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.18) | 1.34 (1.23 to 1.46) |

| Former | 1.15 (0.92 to 1.24) | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.21) | 1.21 (0.95 to 1.39) |

| Current | 1.07 (1.00 to 1.32) | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.17) | 1.15 (1.02 to 1.45) |

| Total (reference value) | 1.17 (1.11 to 1.24) | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.15) | 1.29 (1.20 to 1.38) |

EPHT, Estonian Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy; RR, relative risk.

The selection was different by marital status: the variation in different risk was about 17% (RR from 0.98 to 1.15) in eligibility, whereas the variation in willingness was only 5% (RR from 1.13 to 1.18). The differential attendance according to marital status varied from 1.11 to 1.33. The differential attendance was low among single women and rather uniform in other marital groups.

Never-smokers had a higher differential willingness than current or former smokers (RR 1.20, 1.07, 1.15, respectively). The differential eligibility was also highest among non-smokers (RR 1.11, 1.05, 1.08). Therefore, the same trend remained in the ultimate attendance (RR 1.34, 1.15, 1.21, respectively).

The presence of respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms had a stronger effect on exclusion from the blind subtrial compared with the non-blind subtrial. Willingness was higher in the non-blind subtrial regardless of the presence of these symptoms, and the same applied to eligibility, for example, the differential eligibility when comparing the lack-of-breath symptom was 1.06 if the symptom was not reported and 1.22 if the woman had reported the symptom (table 2). The differential eligibility for women with and without stomach ache was 1.28 and 1.07, respectively, and for women with and without diarrhoea/constipation, it was 1.22 and 1.06, respectively.

Table 2.

Relative probabilities (RR, non-blinded vs blinded subtrial) of the willingness by woman and of the eligibility by doctor and the ultimate attendance by the woman's symptoms, EPHT Trial

| Symptom* | Willingness (95% CI) | Eligibility (95% CI) | Attendance (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of breath | |||

| No | 1.21 (1.13 to 1.31) | 1.06 (1.00 to 1.13) | 1.30 (1.17 to 1.42) |

| Yes | 1.11 (0.97 to 1.27) | 1.22 (1.08 to 1.38) | 1.36 (1.13 to 1.62) |

| Diarrhoea or constipation | |||

| No | 1.12 (1.04 to 1.21) | 1.06 (0.99 to 1.13) | 1.19 (1.07 to 1.32) |

| Yes | 1.32 (1.17 to 1.47) | 1.22 (1.07 to 1.21) | 1.55 (1.33 to 1.81) |

| Stomach pain | |||

| No | 1.17 (1.09 to 1.26) | 1.07 (1.00 to 1.14) | 1.25 (1.14 to 1.37) |

| Yes | 1.16 (0.99 to 1.37) | 1.28 (1.05 to 1.36) | 1.48 (1.17 to 1.88) |

| Swelling | |||

| No | 1.20 (1.12 to 1.30) | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.21) | 1.28 (1.17 to 1.42) |

| Yes | 1.04 (0.91 to 1.19) | 1.20 (1.05 to 1.36) | 1.24 (1.03 to 1.50) |

| Hot flushes | |||

| No | 1.17 (1.07 to 1.28) | 1.12 (1.03 to 1.21) | 1.31 (1.16 to 1.47) |

| Yes | 1.17 (81.08 to 1.27) | 1.06 (1.00 to 1.14) | 1.27 (1.12 to 1.38) |

| Sweating | |||

| No | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.28) | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.19) | 1.27 (1.13 to 1.44) |

| Yes | 1.18 (1.08 to 1.28) | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.17) | 1.29 (1.16 to 1.43) |

| Total (reference value) | 1.17 (1.11 to 1.24) | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.15) | 1.29 (1.20 to 1.38) |

*Those with the symptom unknown are excluded.

EPHT, Estonian Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy; RR, relative risk.

Hot flushes are one of the main reasons for menopausal HT. This symptom did not differentiate with regard to willingness (RR 1.17 in those with or without the symptom). In eligibility there was a small differential preference in favour of the non-blind subtrial in those without the symptom (RR 1.12 vs 1.06). The attendance rates for women with or without hot flushes did not differ much between the blind and non-blind subtrial (RR 1.31 and 1.27, respectively). Sweating, another typical menopausal symptom also showed no differences.

Discussion

In the EPHT Trial there was an increase in the ultimate attendance (29%) if the trial was not blind. Both the women (17%) and the physicians (10%) favoured the non-blind trial.6 In this paper we show that joining a blind or non-blind subtrial was affected by the woman's background factors, specifically related to the social position of the woman and to her symptoms. The differential willingness of the woman was more related to her socioeconomic characteristics, while the eligibility criteria by physicians was more related to the woman's symptoms, even if she was not falling in the exclusion criteria. The more skewed the distribution, the more selection was caused by these specific background characteristics. The main indications of HT, hot flushes and sweating, did not affect differentially either willingness or eligibility.

Earlier we have shown7 that the risks of coronary heart diseases, cerebrovascular events, bone fractures, total mortality and all events together were smaller in the blind placebo control group than in the non-blind control group. We hypothesised that this may have resulted from the selection bias caused by the different background characteristics of the women, the difference in seeking medical advice during the trial due to knowing whether they would receive treatment or not, or from the delay in diagnosis by physicians due to blinding. We have now analysed the differential effect of women's background characteristics on willingness, eligibility and attendance during the recruitment process. The EPHT Trial was conducted several years ago, but the analysis of the effect of blinding on trial attendance is not time critical.

The risk factor profile was recorded before the start of the intervention. Education and smoking are strongly related to the woman's socioeconomic position and to the risk of specific diseases and overall health. Current smokers with high risk preferred the non-blind arm, which is consistent with the low risk of diseases observed in the blind placebo controls.

The doctor should have applied the symptoms as exclusion criteria more persistently and more frequently in the blind than in the non-blind subtrial. This is consistent with the observed disease differences by arm, if the symptoms predicted the chronic diseases recorded in the EPHT Trial. However, this potential explanation was to some extent eliminated by the willingness of a woman to accept the blind subtrial less consistently if she had symptoms. The overall effect was not totally neutral after this interaction and the differences in diseases could possibly be accounted for by the symptoms and their effect on the woman's differential eligibility.

In summary, it is credible that the background characteristics of the women attending the EPHT Trial account for some of the lower risk of trial outcomes in placebo controls compared with non-blind controls. We have incorporated the CI in the tables. However, we hope that the statistical significance of the estimates of selection (RR) were not emphasised too much. This is because our objective is measured by variation in RR within a background variable. The magnitude of this variation is the point: no need to adjust if small; however, there is need to consider if it is large, independent of its significance.

We do not know whether the women asked for extraneous information to decide whether to join the trial or not. Anyhow, our design mimics the actual decision-making of a participant without the direct influence of the study investigators. We assume that the willingness mainly reflects the decision of the woman and indicates the preference for a non-blind trial. It is also possible that the study physician allowed the discussion with the participant and her preferences to affect the exclusion criteria. Thus, the ultimate decision was probably more or less a combined one by the woman and the doctor.

Participants in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been compared with the general population, and their lower risk profile has been noted.13 We have previously shown6 that blinding reduces the willingness of the participant and eligibility as defined by the trial in the randomised trial of EPHT. In this paper we have shown that the difference in attendance was differentially related to the participant's background characteristics, which were predictive as to the trial outcome. Therefore, blinding may have implications for the comparability and generalisability of RCTs.

Other aspects of blinding that may affect the trial results, for example, the effect of blinding on behaviour, deserves further research. As blinding may have a notable effect on trial outcomes, this effect should be taken into account for improving the PRECIS tool14 for designing pragmatic trials, as well as in the extension of the CONSORT statement for pragmatic trials.15

Footnotes

Contributors: MH and EH planned the trial; PV and S-LH conducted the data collection; PV drafted the paper. KF is responsible for the data analyses, while all authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Committees of Medical Ethics in Tallinn, Estonia and Tampere, Finland.

Data sharing statement: Study protocol available at ISRCTN registry: http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN35338757

References

- 1.Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL et al. . Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2008;336:601–5. 10.1136/bmj.39465.451748.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feys F, Bekkering GE, Singh K et al. . Do randomized clinical trials with inadequate blinding report enhanced placebo effects for intervention groups and nocebo effects for placebo groups? Syst Rev 2014;3:14 10.1186/2046-4053-3-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ et al. . Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273:408–12. 10.1001/jama.1995.03520290060030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hrobjartsson A, Emanuelsson F, Skou Thomsen AS et al. . Bias due to lack of patient blinding in clinical trials. A systematic review of trials randomizing patients to blind and non-blind sub-studies. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:1272–83. 10.1093/ije/dyu115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunz R, Vist G, Oxman AD. Randomisation to protect against selection bias in healthcare trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2):MR000012 10.1002/14651858.MR000012.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemminki E, Hovi SL, Veerus P et al. . Blinding decreased recruitment in a prevention trial of postmenopausal hormone therapy. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:1237–43. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veerus P, Fischer K, Hakama M et al. . EPHT Trial. Results from a blind and a non-blind randomised trial run in parallel: experience from the Estonian Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy (EPHT) Trial. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:44 10.1186/1471-2288-12-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veerus P, Hovi SL, Fischer K et al. . Results from the Estonian postmenopausal hormone therapy trial [ISRCTN35338757]. Maturitas 2006;55:162–73. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veerus P, Fischer K, Hovi SL et al. . Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases use of health services: experience from the Estonian Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy Trial [ISRCTN35338757]. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:62–71. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veerus P, Fischer K, Hovi SL et al. . Symptom reporting and quality of life in the Estonian Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy Trial. BMC Womens Health 2008;8:5 10.1186/1472-6874-8-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hovi SL. Preventive Trial on Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy in Estonia. https://tampub.uta.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/67592/951-44-6629-2.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 27 Nov 2015).

- 12.Jewell NP. Statistics for epidemiology. 1st ed London: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy-Martin T, Curtis S, Faries D et al. . A literature review on the representativeness of randomized controlled trial samples and implications for the external validity of trial results. Trials 2015;16:495 10.1186/s13063-015-1023-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F et al. . The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 2015;350:h2147 10.1136/bmj.h2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ et al. . for the CONSORT and Pragmatic Trials in Healthcare (Practihc) groups. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ 2008;337:a2390 10.1136/bmj.a2390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]