Abstract

Purpose of the study

Glaucoma, a chronic non-communicable disease, and leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide is a public health problem in Nigeria, with a prevalence of 5.02% in people aged ≥40 years. The purpose of this nationwide survey was to assess Nigerian ophthalmologists’ practice patterns and their constraints in managing glaucoma.

Study design

Ophthalmologists were sent a semistructured questionnaire on how they manage glaucoma, their training in glaucoma care, where they practice, their access to equipment for diagnosis and treatment, whether they use protocols and the challenges they face in managing patients with glaucoma.

Results

153/250 ophthalmologists in 80 centres completed questionnaires. Although 79% felt their training was excellent or good, 46% needed more training in glaucoma diagnosis and surgery. All had ophthalmoscopes, 93% had access to applanation tonometers, 81% to visual field analysers and 29% to laser machines (in 19 centres). 3 ophthalmologists had only ophthalmoscopes and schiøtz tonometers. For 85%, a glaucomatous optic disc was the most important feature that would prompt glaucoma work-up. Only 56% routinely performed gonioscopy and 61% used slit-lamp stereoscopic biomicroscopy for disc assessment. Trabeculectomy (with/without antimetabolites) was the only glaucoma surgery performed with one mention of canaloplasty. Poor compliance with medical treatment (78%) and low acceptance of surgery (71%) were their greatest challenges.

Conclusions

This study indicates that a systems-oriented approach is required to enhance ophthalmologist's capability for glaucoma care. Strategies to improve glaucoma management include strengthening poorly equipped centres including provision of lasers and training, and improving patients’ awareness and education on glaucoma.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first of its kind, giving insight into available skills, distribution, productivity and training of ophthalmologists in glaucoma care in Nigeria.

Ophthalmologists from across the country and different healthcare sectors were represented.

It was difficult to obtain a comprehensive list of all practising ophthalmologists as some are qualified overseas and not all are registered with the Ophthalmological Society of Nigeria (OSN).

If non-responding ophthalmologists had less access to equipment for diagnosis and treatment, then the equipment available and surgical output may have been overestimated.

Another limitation is that the study relied on recall by the respondents.

Introduction

Glaucoma, a chronic non-communicable disease that leads to progressive damage to the optic disc with loss of visual field, is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide. Blindness from glaucoma is avoidable with early diagnosis and appropriate sustained life-long treatment. The number of people (aged 40–80 years) with glaucoma will increase to 111.8 million by 2040, disproportionately affecting people in Africa.1 The Nigeria National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey showed a high prevalence of glaucoma (5.02%, 95% CI 4.60% to 5.47%) among adults ≥40 years. One in 5 persons with glaucoma was blind and only 1 in 20 had been diagnosed with glaucoma prior to the survey, suggesting poor knowledge of glaucoma and poor access to services for glaucoma care.2

People still go blind from glaucoma in Africa as it is frequently undiagnosed, inadequately treated with poor compliance to treatment regimens;3 due to limited equipment and treatment options, the high cost of care and lack of awareness among patients.4–8 Up to 42% of patients with glaucoma attending hospitals in Nigeria are already blind at the time of diagnosis,9–15 and middle-income earners spend up to 50% of their monthly income on medical therapy for glaucoma which equates to total monthly income among low-income earners.16

In order to prevent blindness from glaucoma in Africa, recent advances in technology for diagnosing glaucoma need to be embraced, together with therapeutic options that are effective, affordable and acceptable, combined with ongoing monitoring which can decrease the risk of blindness.17

The term physician's practice pattern describes the pattern of practice by doctors to diagnose and formulate a plan of care, in this case by ophthalmologists for glaucoma, within their scope of professional practice.18 It is defined as patterns of practice related to diagnosis and treatment as especially influenced by the cost of the service requested and provided.19 Benchmarking practice patterns according to recommended guidelines has important implications for quality of care.

The UK's guidelines (the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NICE) recommend that glaucoma be diagnosed using applanation tonometry to measure intraocular pressure (IOP), measurement of central corneal thickness, assessment of anterior chamber angle, visual fields analysis and optic nerve head (ONH) assessment with dilation, using slit-lamp biomicroscopy with a condensing lens (Hruby lens or+60/78/90 dioptres).20 The NICE diagnostic protocol is similar to recommendations by the International Council of Ophthalmology (ICO)21 and the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO).22 ICO also recommends documentation of ONH morphology and retinal nerve fibre assessment with colour stereophotography or computer-based image analysis.

NICE recommend a prostaglandin analogue (PGA) or a β-blocker as first-line topical treatment. Surgery with antimetabolites is reserved for those at risk of vision loss despite medical treatment. However, in Africa, one-off procedures such as surgery or laser treatment are recommended due to low compliance with topical medication and the ongoing out-of-pocket expenditure this entails.9 16 The economic burden on the patient is influenced by the lifetime nature of the treatment as well as the cost of medications.

This study was undertaken to explore current practice patterns of glaucoma care by ophthalmologists in Nigeria and to identify what glaucoma treatments are available and how much they cost. The paper describes management of glaucoma only in patients who come to health facilities where there is an ophthalmologist. We discuss ophthalmologists' practice patterns using the systems thinking concept to try to understand how care provision can be influenced by linkages and interactions between the six components of the health system.23 The information obtained will be disseminated to ophthalmologists and also used for advocacy to hospital managers and policymakers. The systems thinking approach provides new opportunities to understand processes and enable shared development of interventions24 by these groups to improve services for glaucoma care.

Methods

Between September 2010 and July 2012, information sheets for consent to participate and semistructured questionnaires with a space for comments were delivered to ∼250 Nigerian ophthalmologists listed in the databases of the Ophthalmological Society of Nigeria (OSN) and the West African College of Surgeons (WACS). Distribution was to all ophthalmologists participating at the 2010 OSN conference and subsequently by email and phone interviews for initial non-responders and also those not attending the 2010 OSN conference. These avenues for data collection were used for convenient access to ophthalmologists. There were no financial incentives to participate, which was encouraged by reminder emails and telephone calls. Confidentiality and anonymity of responses were maintained.

Information was obtained regarding providers' patterns of care provision. Ophthalmologists were asked about their training/professional background, facility/hospital of practice, availability of functional equipment, and their protocol for glaucoma diagnosis and treatment. Data were collected at individual level as some ophthalmologists worked in more than one facility. They were asked what they considered to be optimum treatment under ideal circumstances, and how they managed their last 10 patients with glaucoma. They were asked to provide information on the number of glaucoma surgeries and cataract surgeries they perform in an average 3-month period, to estimate the ratio of glaucoma-to-cataract surgeries, and to recall surgical complications in relation to use of antimetabolites. Other questions covered systems-related issues such as the cost and availability of glaucoma medication and surgery in their facility, and challenges they faced in glaucoma management.

Descriptive analysis was undertaken using Stata V.14.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). The distribution of ophthalmologists by healthcare geopolitical zones and states was determined but the findings are reported nationally. Missing data were excluded.

Ethical approval was obtained from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria.

Results

A total of 153/250 ophthalmologists from 80 centres returned questionnaires (61% response rate). Out of these, 72 (47%) were completed by respondents at the 2010 OSN conference, while the rest were completed and returned by email or by phone.

Demographic details and training background of ophthalmologists

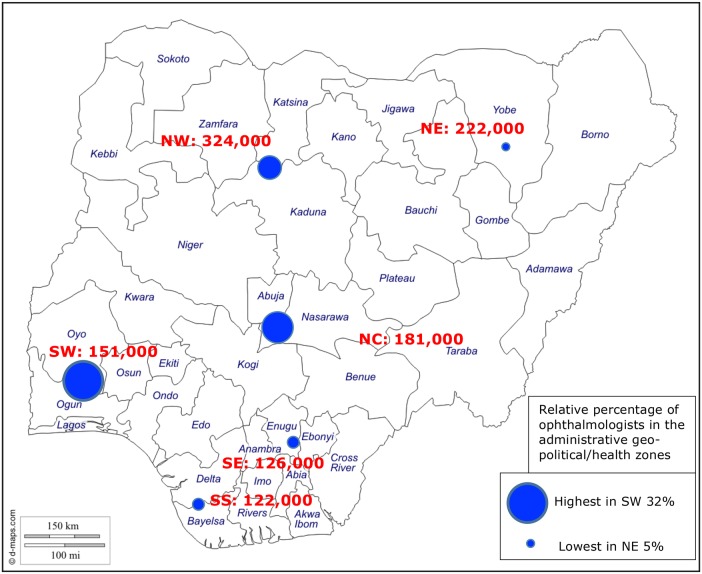

Respondents were aged 34–68 years (median 46 years), 43% were female and the highest number (48; 32%) practised in the south-west (SW) zone where Lagos is situated (figure 1). All ophthalmologists were based in cities, with 50% in Lagos, Abuja, Kaduna and Ibadan, which also have training institutions.

Figure 1.

Map of Nigeria showing the magnitude of blindness and distribution of responding ophthalmologists in the six geopolitical zones. NC, north-central; NE, north-east; NW, north-west; SE, south-east; SS, south-south; SW, south-west.

A high proportion (87%) of respondents had fellowship training in ophthalmology. The number of years since qualification was 1–38 years. Training in glaucoma management was reported as good (62%), fair (18%) and excellent (17%). Thirty-eight per cent had undergone subspecialty training, being higher among those who qualified more than 16 years ago. Ten (7%) had subspecialty training in glaucoma.

The majority of respondents (97%) engaged in continuous medical education (CME) with 87/118 (74%) and 116/138 (84%) attending three or more courses or conferences, respectively, in the previous 3 years. Other sources of CME were online educational resources and medical journals.

Ophthalmology practice

Ophthalmologists practised in government hospitals (63%), private practice (28%), non-governmental/mission hospitals (6%) and military hospitals (3%). About half (75/145; 52%) practised in teaching/tertiary institutions and 33/145 (23%) in state government hospitals. Half (75/150; 50%) said their hospitals ran subspecialty clinics, the most frequent being for glaucoma, paediatric ophthalmology, vitreoretina, oculoplastics, cornea and neuro-ophthalmology.

Most patients (95%) accessed services via walk-in clinics and from community-based outreach screening (73%). Most ophthalmologists (71%) reported that their hospital did not have a written protocol for glaucoma care.

Equipment

Equipment that was available/functional/used in glaucoma management is indicated in table 1. Three ophthalmologists had access to only ophthalmoscopes and schiøtz tonometers.

Table 1.

Equipment available and used for glaucoma diagnosis and care

| Equipment | Available n (%) | Used n (%) | Remarks per cent is of N=146 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ophthalmoscope | 152 (99) | 142 (93) | |

| Applanation tonometer | 142 (93) | 127 (83) | |

| Schiøtz tonometer | 107 (70) | 39 (25) | |

| Other tonometer | 76 (50) | 53 (35) | Non-contact air puff |

| Gonioscope | 130 (85) | 101 (66) | |

| Slit-lamp lens | 136 (89) | 113 (74) | |

| Binocular indirect ophthalmoscope | 133 (87) | 89 (58) | |

| Visual field analyser | 123 (80) | 104 (68) | |

| Fundus camera | 70 (46) | 50 (33) | |

| Ultrasound scan | 88 (58) | 58 (38) | |

| Optical coherence tomography | 41 (27) | 30 (20) | In 14 centres |

| Scanning laser ophthalmoscope | 5 (3) | 2 (1) | In 1 centre |

| Laser | 44 (29) | 23 (15) | In 19 centres |

| Pachymeter | 7 (5) | 4 (3) | 1 each in 7 centres |

| HRT II | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

HRT, Heidelberg retina tomography.

Service delivery of glaucoma care

Examination and diagnosis

Ophthalmologists saw 3–200 new patients with glaucoma over a 3-month period, with an average of 43 per doctor (SD 37). The most important clinical feature that would prompt a glaucoma work-up was suspicious ONH morphology (85% of respondents) and 7% indicated IOP.

When asked how they examined patients with glaucoma, 96% performed cup:disc ratio assessment, 94% measured IOP, 88% assessed visual fields and only 56% performed gonioscopy on all patients. Fewer than 20% routinely performed ONH imaging or assessed corneal thickness. For ONH assessment, most ophthalmologists used a direct ophthalmoscope, 61% used slit-lamp biomicroscopy, 14% used a fundus camera and 11% also used optical coherence tomography.

Glaucoma surgery

Among those providing data on their last 10 patients with glaucoma, 54% patients were offered glaucoma surgery, 35% accepted it and 28% actually underwent surgery (ie, approximately half of those offered surgery underwent the procedure). Of the 124 respondents providing data for an average 3-month period, 60 (48%) performed 5 or fewer glaucoma surgeries and 12 (10%) performed ≥15. There was a wide variation in the number of glaucoma surgeries compared with cataract operations. Overall, ∼1000 glaucoma surgeries were performed in 3 months compared with ∼6500 cataract operations, giving an average ratio of 1:6.5. However, 80% of ophthalmologists had a ratio of at least 1:10.

Trabeculectomy, with/without antimetabolites or releasable sutures, was the only surgery performed for glaucoma in the preceding 3 months, apart from one canaloplasty. Antimetabolites were used by 88% of surgeons. Only 44% of hospital pharmacies provided antimetabolites and some ophthalmologists obtained these agents privately albeit with difficulty.

The main complications following the last 10 trabeculectomies with antimetabolites were ocular hypotony, cystic blebs, thinned/leaking blebs and shallow anterior chambers. Only 24 (18%) reported that they had audited their last 10–50 glaucoma surgeries.

Regarding follow-up, 68% of respondents did not have a standard written follow-up plan: 70% would give an appointment and hope the patient attended; 20% sent reminders by text, phone or email to non-attenders, or home visits were made. First-degree relatives were requested to attend for glaucoma ‘all the time’ by 60% of respondents, and ‘sometimes’ by 34%.

Implications of health financing

Cost of glaucoma treatment

In total, 113/136 (83%) of respondents knew the cost of the medications available in their facility which ranged from 1000 to 50 000 Nigerian Naira (NGN) (approximately £4–£200) for 1 month's supply, depending on the type/brand). All pharmacological groups of antiglaucoma medication were available and 97% had both β-blockers and PGAs to prescribe. The cost of surgery ranged from NGN2000 to 190 000 (approximately £8–£760) which was sometimes provided free by non-governmental organisations.

Choice of treatment

Ophthalmologists were asked what treatment they would offer patients with glaucoma if all equipment and treatment options were available to them, and if cost was not a barrier. Over half (54%) chose surgery, mostly trabeculectomy with/without antimetabolites which inhibit scarring, while 41% preferred medical therapy with PGAs. Two doctors preferred laser treatment—trabeculoplasty and selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT). However, most ophthalmologists would modify their choice, or offer a combination of treatment based on risks and benefits, taking account of disease severity at diagnosis (84%), acceptability (75%), availability (54%) and cost (53%). Other considerations included age, access to care and follow-up, compliance to treatment, family history of glaucoma and coexisting conditions.

Challenges in glaucoma care

The challenges in glaucoma care cited by respondents can be categorised into provider-related, patient-related and health systems-related. Provider-related challenges included fear of surgical complications, their inability to offer a cure or improve patients' vision and the uncertainty of postoperative outcomes. Difficulties in postoperative care were also reported. Patient-related challenges included poor compliance with medical treatment, low acceptance of glaucoma surgery, poor awareness and understanding of glaucoma, poor access to care, late presentation, and poor compliance with follow-up. Health systems-related challenges included lack of equipment and medication, cost of treatment and a need for more training in early glaucoma diagnosis and in glaucoma surgery.

The ophthalmologists made other comments, highlighting their needs and challenges and how they are being addressed.

Provider-related:

Glaucoma is such a big burden and the challenges posed by its management are enormous in our setting. The uptake of surgery…is low but with the advent of SLT [laser treatment], a lot more are taking up SLT as adjunct in our centre and so far we are recording successes with regards to IOP control.

There is the need for refractive correction before and after surgical intervention.

Another important practice I observe is to request the presence of spouse/next-of-kin in the pre-op counselling sessions. I am never in a hurry to proceed to surgery.

Patient-related:

Most of our patients present very late and expect treatment.

(There are) issues of patients understanding of disease progression despite surgery.

We have a Glaucoma Patient Club/Association…

Health systems-related:

We need to look at acceptable ways for screening and case-finding in the communities rather than waiting for them to come with advanced, late stage disease.

Treatment options are limited: drugs—by cost and availability; laser and surgery—by availability and expertise.

Ophthalmologists highlighted their need for further training:

Major challenges are (few) opportunities for training and retraining in glaucoma management.

All practising ophthalmologists should be trained on how to manage glaucoma well.

Lack of equipment and maintenance were of concern:

We don't have an operating microscope for trabeculectomy and no perimeter to assess functional damage and progression.

Our major constraint is non-availability of both diagnostic and surgical equipment and instruments.

Essential equipment like field analyser & OCT require technical support that is not available in the country.

There is a need for an articulated national protocol for diagnosis and treatment of glaucoma.

Discussion

This study, which describes ophthalmologists' practice patterns in relation to glaucoma in Nigeria, is the first of its kind, giving insight into available skills, distribution, productivity and training of ophthalmologists in glaucoma care in Nigeria.

This paper focuses on the human resources for glaucoma care from the perspective of the ophthalmologist. Other allied eye health personnel and the team for glaucoma care were not addressed in this survey. In 2011, Nigeria had an estimated 3.2 ophthalmologists per million population which is just below the ophthalmologist-to-population ratio of 4 per million recommended by VISION2020, which will not be achieved by 2020 without additional intervention.25 However, the overall figure of 3.2 per million masks maldistribution of ophthalmologists within the country, as the north-east is less well served than the SW, and more needs to be done to encourage ophthalmologists to work in the north. The southern city of Lagos has a large number of ophthalmologists, but there is a shortage of allied eye health personnel who play an important role in glaucoma care.26

Training in leadership and management is essential as it would support glaucoma services at the hospital.27 Given the high prevalence of glaucoma blindness, there is a need for competency-based training for early detection, and surgical and laser treatment of glaucoma, so that all ophthalmologists in Nigeria can manage the condition at secondary and tertiary levels, which would enable glaucoma specialists to focus on more complex cases at the tertiary level. In Africa, there is increasing momentum to improve glaucoma care, encapsulated by the resolution of a meeting in Kampala, Uganda, in 2012.28 Nigeria now has a glaucoma society (Nigeria Glaucoma Society, NGS), and there are subspecialty training initiatives for glaucoma in the region, such as that in Ghana. Clinical fellowships are also offered by ICO and the Commonwealth Eye Health Consortium.

However, current training has not yet translated into written protocols, their use and challenges. The NGS needs to develop national glaucoma guidelines appropriate to the local context, which include minimal essential diagnostic examination procedures and recommendations on primary treatment.

In this study, training in ophthalmology was reported as excellent by 17% and good by 62%. However, it is noteworthy that there was no specific or detailed information on training. It may seem contradictory that there was request for more training in glaucoma care by some respondents. Young ophthalmologists need to be encouraged to develop competencies in glaucoma early in their careers, with self-audit being an integral component of the training. Prospective monitoring is also essential and can gauge surgical competencies and outcomes.

Ophthalmologists in our study reported high levels of CME. Free online access to journals, such as that provided by the WHO HINARI programme, ONE Network and African Journals Online (AJOL) platforms, is immensely useful as most training institutions or hospitals do not prioritise journal subscriptions.

In our study, service delivery in relation to the management of glaucoma fell short of NICE, ICO and AAO recommendations in several respects, in part due to lack of equipment but also because of late presentation, where visual field assessment is not possible, for example, and low adherence to medical and surgical treatment and follow-up. Similar challenges have been reported in Botswana.29

Advocacy will be required with the government to strengthen infrastructure and provide appropriate equipment (with maintenance) in all eye care centres across the country. In this study, ophthalmologists reported that laser was a more acceptable form of treatment than trabeculectomy, and equipment and skills in laser treatment need to be expanded.

Surgery was the treatment of choice in this study, but only about half of patients offered surgery underwent the procedure. Several authors have recommended surgery as first-line treatment for glaucoma in Africa, including in Port-Harcourt where all consecutive patients with glaucoma enrolled in a study were on medical therapy as all had refused surgery. Medical treatment was too expensive for many patients, leading to non-compliance and loss to follow-up.16 Research is needed on interventions which improve acceptance of surgery, and a randomised control trial of motivational interviewing adapted for glaucoma is currently being undertaken in Nigeria, in which patients are supported to overcome obstacles to accepting surgery or laser.30 Studies are also required on different forms of laser treatment in Africa. Micropulse diode laser trabeculoplasty has been used with adjunctive effect,31 and a prospective, observational study of trans-scleral cyclodiode laser photocoagulation as first-line or second-line treatment for patients with advanced glaucoma is ongoing, to assess the effectiveness of these modes of laser treatment which are acceptable and easier to deliver than trabeculoplasty (Abdull MM, personal communication 2015).

Medical therapy with PGAs was the second commonest treatment choice in our study, which were available but expensive. In a hospital study in Benin, there was no significant difference between cost of medication compared with surgical treatment over a 3-year period up to 2008,32 but this was before PGAs became widely available. Indeed, the clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of newer medications versus surgery with antimetabolites is not known.33 Another trial is taking place in Tanzania, in which SLT is being compared with timolol (Heiko P, personal communication 2015). Audit of outcomes of treatment in black ethnic groups will enable evidence-based choices to be made. Other factors which may improve compliance with medical therapy include policies on marketing, non-branding and cost, and inclusion of PGAs in health insurance schemes.

There was wide variation in the number of glaucoma surgeries reported. The highest number (150 in 3 months) were performed in a high-volume centre where most patients have advanced disease and compliance with medical therapy and follow-up is poor. In this centre, glaucoma surgery is offered to all patients at diagnosis, and performed almost immediately at a highly subsidised cost (respondent, personal communication 2015). The reduced cost seemed to be an important factor contributing to the high volume. Glaucoma surgery needs to be included in universal health coverage and health insurance schemes.

In our study, poor follow-up was a problem. Robust health information systems are important in patient flow and follow-up. Indeed, a hospital study in Benin showed that ≥70% of patients with glaucoma either failed to reattend after diagnosis, or within 9 months. Poor follow-up was associated with worse stage of glaucoma, poorer visual acuity and age.34 Follow-up may be improved by patient counselling and education, reminders by text, email, phone and community follow-up, and by improving the hospital visit experience for patients.

Patient-related factors contribute to the main challenges of glaucoma care. An important reason for late presentation by patients with glaucoma is lack of awareness about glaucoma.15 It would be useful to develop a health education pamphlet for the local context, suitable for all including those who are not literate.27 There is also a need to develop primary-level and community-based case-finding strategies to improve opportunities for early intervention.35

A strength of the study is that ophthalmologists from across the country and different healthcare sectors were represented. A limitation of this study was that it was difficult to obtain a comprehensive list of all practising ophthalmologists as some qualified overseas and not all are registered with the OSN. If non-responding ophthalmologists had less access to equipment for diagnosis and treatment, then the equipment available and surgical output may have been overestimated. Another limitation is that the study relied on recall. The eye care team was not addressed in this study.

Further areas of operational research would be the development and investigation of glaucoma care teams involving primary eye care workers for early case detection in the community and other allied eye health personnel for refraction and vision care, counselling, health education and follow-up of glaucoma suspects and patients with glaucoma. This study could also form the baseline to assess the impact on practice patterns following the introduction and dissemination of clinical guidelines.

Conclusion

This study indicates that a health systems-oriented approach is required to overcome the major obstacles to providing optimal glaucoma care. Strategies include leadership by the NGS to develop national guidelines and benchmark for service delivery of glaucoma care; infrastructural strengthening for diagnostic and therapeutic/surgical equipment with provision of lasers and training; and medicines. Strategies to improve glaucoma management also include development of healthcare financing strategies through universal health coverage and health insurance schemes; operational/implementation research to develop methods for early diagnosis and robust referral/feedback systems and patients' health information systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Martha Martin and Peter Martin for data entry. The findings were presented, in part as a paper, at the Ninth General Assembly of the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB), Hyderabad, India, September 2012.

Footnotes

Contributors: FK led the conception and design of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the manuscript and edited it with consideration from reviewers’ and co-authors’ comments. WN contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of data and revised the article for important intellectual content. CG supervised the conception and design of the study, interpreted the data and revised the article for important intellectual content.

Funding: The study was supported by the Fred Hollows Foundation (http://www.hollows.org.au/). Grant code ITCRVW04.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and National Health Research Ethics Committee of Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY et al. . Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2014;121:2081–90. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyari F, Entekume G, Rabiu M et al. . on behalf of the Nigeria National Blindness and Visual Impairment Study Group. A population-based survey for the prevalence and types of glaucoma in Nigeria. The Nigeria National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey. BMC Ophthalmol 2015;15:176 10.1186/s12886-015-0160-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Susanna R Jr, De Moraes CG, Cioffi GA et al. . Why do people (still) go blind from glaucoma? Transl Vis Sci Technol 2015;4:1–12. 10.1167/tvst.4.2.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egbert PR. Glaucoma in West Africa: a neglected problem. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:131–2. 10.1136/bjo.86.2.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omoti AE. A review of the choice of therapy in primary open angle glaucoma. Niger J Clin Pract 2005;8:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rotchford A. What is practical in glaucoma management? Eye 2005;19:1125–32. 10.1038/sj.eye.6701972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olatunji FO, Ibrahim UF, Muhammad N et al. . Challenges of glaucoma service delivery in Federal Medical Centre, Azare, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci 2008;37:355–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Standefer JE. Challenges in glaucoma management in developing countries: is Vision2020 ready for glaucoma? Niger J Ophthalmol 2009;18:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook C. Glaucoma in Africa: size of the problem and possible solutions. J Glaucoma 2009;18:124–8. 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318189158c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashaye AO. Clinical features of primary glaucoma in Ibadan. Niger J Ophthalmol 2003;11:70–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Omoti AE, Osahon AI, Waziri-Erameh MJ. Pattern of presentation of primary open-angle glaucoma in Benin City, Nigeria. Trop Doct 2006;36:97–100. 10.1258/004947506776593323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawan A. Pattern of presentation and outcome of surgical management of primary open angle glaucoma in Kano, Northern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med 2007;6:180–5. 10.4103/1596-3519.55700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olatunji FO, Ibrahim UF, Muhammad N et al. . The types and treatment of glaucoma among adults in North Eastern part of Nigeria. Tanzan Med J 2009;24:24–8. 10.4314/tmj.v24i1.46419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adekoya BJ, Shah SP, Onakoya AO et al. . Glaucoma in southwest Nigeria: clinical presentation, family history and perceptions. Int Ophthalmol 2014;34:1027–36. 10.1007/s10792-014-9903-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdull MM, Gilbert CC, Evans JR. Primary open angle glaucoma in northern Nigeria: stage at presentation and acceptance of treatment. BMC Ophthalmol 2015;15:111 10.1186/s12886-015-0097-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adio AO, Onua AA. Economic burden of glaucoma in Rivers State, Nigeria. Clin Ophthalmol 2012;6:2023–31. 10.2147/OPTH.S37145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malihi M, Moura Filho ER, Hodge DO et al. . Long-term trends in glaucoma-related blindness in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology 2014;121:134–41. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dictionary, Medical Dictionary for Health Professions and Nursing @ Farlex 2012. http://www.medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com (Last accessed 17 Jul 2016).

- 19.Reference.MD. Physician's practice patterns 2012. http://www.reference.md/files/D010/mD010818.html (Last accessed 19 Jul 2016).

- 20.Glaucoma. Commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Diagnosis and management of chronic open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Methods, evidence and guidance. April 2009. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG85 (accessed 11 Aug 2015).

- 21.International Council of Ophthalmology. ICO guidelines for glaucoma eye care. http://www.icoph.org/ICOGlaucomaGuidelines.pdf 2016. (Last accessed 9 Jun 2016).

- 22.American Academy of Ophthalmology. Primary open-angle glaucoma. Preferred practice pattern. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2016. http://www.aaojournal.org/article/S0161-6420(15)01276-2/pdf (Last accessed 9 June 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Savigny D, Adam TE. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening: an introduction. Alliance for Health policy and systems research, WHO, 2009:27–36. http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/9789241563895/en/ (Last accessed 17 Jul 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters DH. The application of systems thinking in health: why use systems thinking? Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:51 10.1186/1478-4505-12-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer JJ, Chinanayi F, Gilbert A et al. . Trends and implications for achieving VISION 2020 human resources for eye health targets in 16 countries of sub-Saharan Africa by the year 2020. Hum Resour Health 2014;12:45 10.1186/1478-4491-12-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adekoya BJ, Shah SP, Adepoju FG. Managing glaucoma in Lagos State, Nigeria—availability of Human resources and equipment. Niger Postgrad Med J 2013;20:111–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdull MM. Glaucoma care at ATBUTH eye clinic, Bauchi. Community Eye Health 2014;27:53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prevention of Blindness Union (PBU) in collaboration with International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB) Africa. Africa glaucoma control meeting. Kampala, Uganda: Kampala Resolution; 2012. http://www.pbunion.org/files/Full%20Workshop%20report%202%20Mayfinal2docx.pdf (Last accessed 13 Aug 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Razai MS, Jackson DJ, Falama R et al. . The capacity of eye care services for patients with glaucoma in Botswana. Ophthal Epidemiol 2015;22:403–8. 10.3109/09286586.2015.1010689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdull MM, Gilbert C, McCambridge J et al. . Adapted motivational interviewing to improve the uptake of treatment for glaucoma in Nigeria: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:149 10.1186/1745-6215-15-149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Babalola OE. Micropulse diode laser trabeculoplasty in Nigerian patients. Clin Ophthalmol 2015;9:1347–51. 10.2147/OPTH.S82678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Omoti AE, Edema OT, Akpe BA et al. . Cost analysis of medical versus surgical management of glaucoma in Nigeria. J Ophthal Vis Res 2010;5:232–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burr J, Azuara-Blanco A, Avenell A et al. . Medical versus surgical interventions for open angle glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(9):CD004399 10.1002/14651858.CD004399.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anonymous. Glaucoma care in a tertiary facility in Benin City, Nigeria; predictors of poor follow-up and barriers to compliance with treatment [electronic resource]. Uncorrected MSc Project Report LSHTM 2013–2014. 2014. https://intra.lshtm.ac.uk/library/MSc_CEH/2013-2014/107717.pdf. (accessed 5 Oct 2016).

- 35.Olawoye O, Fawole OI, Teng CC et al. . Evaluation of community eye outreach programs for early glaucoma detection in Nigeria. Clin Ophthalmol 2013;7:1753–9. 10.2147/OPTH.S46823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]