Abstract

Introduction

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) poses a serious financial challenge to health systems and patients. The current treatment for patients with MDR-TB takes up to 24 months to complete. Evidence for a shorter regimen which differs from the standard WHO recommended MDR-TB regimen and typically lasts between 9 and 12 months has been reported from Bangladesh. This evaluation aims to assess the economic impact of a shortened regimen on patients and health systems. This evaluation is innovative as it combines patient and health system costs, as well as operational modelling in assessing the impact.

Methods and analysis

An economic evaluation nested in a clinical trial with 2 arms will be performed at 4 facilities. The primary outcome measure is incremental cost to the health system of the study regimen compared with the control regimen. Secondary outcome measures are mean incremental costs incurred by patients by treatment outcome; patient costs by category (direct medical costs, transport, food and accommodation costs, and cost of guardians/accompanying persons and lost time); health systems cost by category and drugs; and costs related to serious adverse events.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been evaluated and approved by the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease; South African Medical Research Ethics Committee; Wits Health Consortium Protocol Review Committee; University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee; University of Kwazulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee; St Peter TB Specialized Hospital Ethical Review Committee; AHRI-ALERT Ethical Review Committee, and all participants will provide written informed consent. The results of the economic evaluation will be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN78372190.

Keywords: Health systems cost, Patient costs, out-of -pocket payments, economic impact of MDR-TB

Strengths and limitations of this study.

STREAM enrols multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients (an understudied but highly burdened population) into trial treatment regimens and economic evaluation will determine health system costs, out-of-pocket payments and financial coping mechanisms in this population.

Health system and patient costs will be collected and analysed for budget impact and economic burden, respectively.

Collecting data from participants across countries and at multiple time points has inherent challenges, including loss to follow-up and participant heterogeneity.

Background

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is a form of tuberculosis resistant to isoniazid (INH) and rifampicin, two of the most important first-line TB drugs.1 2 The WHO estimates that, globally in 2012, over 450 000 people developed MDR-TB, and 170 000 people died of MDR-TB.1–3 In contrast to drug-susceptible TB, which is treatable in 6 months, patients with MDR-TB are treated for a minimum of 20 months. The costs of treating MDR-TB are much greater than treating drug-susceptible TB, from a health systems and patient perspective.4 For instance, health systems cost per patient for MDR-TB treatment in Estonia, Peru, the Philippines and Tomsk was US$10 880, US$2423, US$3613 and US$14 657, respectively.5 Similarly, in South Africa, the average health systems cost of inpatient treatment for MDR-TB exceeded US$17 000, nearly 40 times the average cost of treating drug-susceptible TB.6

From a patient perspective, a recent systematic review on the financial burden for tuberculosis patient in low-income and middle-income countries has shown that the total cost for patients with MDR-TB is considerably higher than drug-susceptible TB.7 For instance, the total costs as percentage of reported individual income for patients with MDR-TB and patients with drug-susceptible TB in Ecuador and Cambodia were 223% ($14 388) vs 31% ($2008) and 76% (2953) vs 24% ($923), respectively.7

An observational research study from Bangladesh by Van Deun et al8 concluded that shorter standardised treatment regimens lasting up to 12 months are as effective in treating MDR-TB as the current 22-month regimen. Similarly, treatment standardisation has also been advocated as a feasible and potentially effective approach for MDR-TB,9 10 but this has not been evaluated in a clinical trial with a nested economic analysis. While shortening treatment regimens might be expected to reduce costs, this is far from certain. Analysis of patient costs during drug-sensitive tuberculosis treatment in Bangladesh and Tanzania11 suggests that these costs are not incurred steadily over the course of treatment, but occur disproportionately during the intensive phase, implying that cost savings from the shortened regimen may be limited. There is also the potential for increased adverse events in the shortened regimen, which have cost implications. Even if shortened regimens are cost saving overall, detailed information on the nature and timing of costs to patients and health systems is required to inform the planning and delivery of TB services and social protection programmes.

This study therefore aims to assess the economic impact on patients and health systems of the shortened standardised regimen as proposed in the Bangladesh study (study regimen) compared to the locally used WHO-approved MDR-TB (control regimen). The results of this evaluation will provide granular information on the types of costs associated with MDR-TB treatment from a patient and health system perspective, and how adopting shortened regimens will affect the amount and timing of these costs. It will identify the major drivers of these costs and thereby provide a starting point for work to reduce these costs, where possible, without compromising safety or effectiveness. The evaluation will therefore assist decisions about the planning and uptake of shortened MDR-TB treatment regimens in different settings. To achieve this, the economic evaluation will establish the cost associated with the study and control regimens,8 including costs related to serious adverse events (SAE). A societal perspective will be taken, so that health systems and patient costs are included.12 A full description of the main trial and its com-ponents is described in the main trial protocol.13 In this paper, our focus is on the costing methodology of the economic evaluation.

Objectives

The main objective of the economic evaluation is to document how a shortened MDR-TB treatment regimen compared to the control regimen will affect the amount, nature and timing of costs incurred by patients and by the health system with the aim of informing programme management and the design of interventions for patient financial protection.8

The specific objectives of the health economic component in the trial are therefore: (Gospodarevskaya E. The evaluation of a standardised treatment regimen of anti-tuberculosis drugs for patients with MDR-TB (STREAM). Health Economics Guide, 2012,Unpublished guide):

To assess the costs incurred by patients enrolled in the study regimen when compared to the control regimen.

To assess the costs incurred by the health system for the study regimen when compared to the control.

To describe the types of costs incurred by patients and health systems in the management of MDR-TB.

To identify the main drivers of costs in the management of MDR-TB.

Methods and design

Study design

An economic evaluation comparing two arms: study regimen and control or locally used WHO-approved MDR-TB regimen. The study regimen is a modified version of the 9-month regimen based on the one described by Van Deun et al8 and consists of ethambutol, pyrazinamide, moxifloxacin and clofazimine given for 9 months (40 weeks), supplemented by kanamycin, prothionamide and INH in the first 4 months (16 weeks). The only change from the Bangladesh study regimen described by Van Deun et al8 is the substitution of gatifloxacin with moxifloxacin. Patients will be randomised to either the study regimen or control regimen. A detailed description of the study design is available in the main trial protocol.13

Settings

The STREAM trial is taking place in four countries (Ethiopia, Mongolia, South Africa and Vietnam); however, due to research clearance challenges, the economic evaluation will be conducted in two countries (Ethiopia and South Africa). In Ethiopia, the study will be conducted at two major referral health facilities in Addis Ababa. In South Africa, the study will be conducted in two different locations, Johannesburg and Pietermaritzburg, and one healthcare facility in each location. The selection of facilities in each country is based on their experience in treating patients with MDR-TB and support from the Tuberculosis Control Programme at national or regional level and suitable treatment site staff and facilities.

Sampling

The sample size for the overall study is 400 calculated on the basis of expected difference in proportion of favourable clinical outcomes between the control regimen and study regimen with 95% CIs.13 Since the level of patient costs and the expected change as a result of the study regimen is unknown, it is not possible to make an accurate assessment of required sample size for the patient costing survey. A target of 100 patients per country has been selected based on a study by Management Science for Health14 which found this to give a reasonable spread of costs in similar studies in Ethiopia. In addition, a recent study investigating patients' costs during TB treatment in Bangladesh and Tanzania used a sample of about 100 patients per country.11 It is recognised that in countries with lower recruitment rates, this may represent 100% of the study population; in these cases, it is accepted that some patients may choose not to participate in the costing study and that fewer cases, and hence greater uncertainty in the estimates, may be found. Despite this, an economic evaluation can still provide valuable information about costs and benefits of the study regimens.15 However, to ensure full participation, the trial will employ all necessary measures aimed at reducing or avoiding drop-out due to patient costs. These measures will include providing financial support to cater for food, accommodation and transport in both arms of the study.

Intervention design

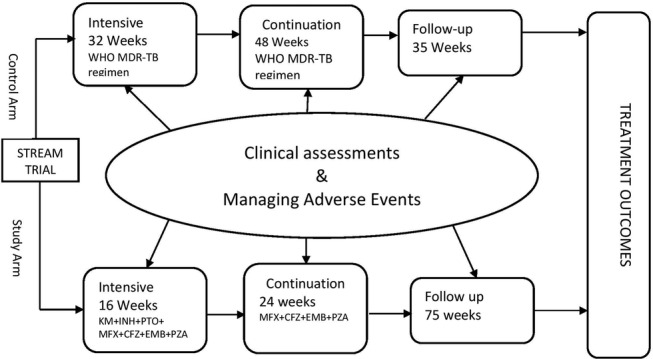

Patients randomised to the control arm will receive usual clinical care based on the application of the ‘WHO guidelines for management of MDR-TB’.16 Patients allocated to the study regimen will be treated at facilities that will have staff trained on the shorter standardised treatment regimen of MDR-TB. To ensure comparability of the two arms in terms of comorbidities, we will use EQ5D-5L to capture health status information. Figure 1 illustrates the pathways followed by patients in arms and summaries of activities at various stages of the treatment process.

Figure 1.

Intervention design, patient pathway and key processes.

Outcome measures

The main health economics-related outcomes will be:14

Mean incremental costs incurred by patients.

Incremental cost to the health system of the study regimen compared with the control regimen (savings will be recorded as negative incremental costs).

Additional health economics outcomes will be:

Mean costs incurred by patients analysed by treatment outcome.

Patient costs by category (direct medical costs, transport, food and accommodation costs, and cost of guardians/accompanying persons and lost time).

Health systems cost by category (training, monitoring, service delivery and drugs).

Costs related to SAE.

Participants

The participants of this study will be patients with MDR-TB and caregivers. Interviewers will explain to all participants that involvement in the study is voluntary and they have the right to withdraw at any point in time and to ask any questions. Information about the study will be translated to Amharic, Zulu and other local languages, and read to all participants and provided in hard copy. In both countries, consent for the health economics component is covered in the main study's consent form (ie, a separate consent form is not used). However, we will obtain consent from health workers to be interviewed (and recorded) and timed.

Costing

Costs will be collected from health system and patient perspectives, and will consider the healthcare resource requirements and patient expenses associated with each treatment arm. Specifically, we will collect data in two resource use areas: (1) healthcare services costs, which include the use of all hospital facilities over the course of the trial, including drugs, medical supplies and laboratory; and (2) patient out-of-pocket expenses, which include the individual's own time (lost time) in the treatment process and associated travel expenses. Health systems costs will include costs incurred at facilities, by each study arm. Patient costs that will be estimated are those incurred in seeking services for MDR-TB healthcare. The trial is expected to report its main outcomes in 2017, so all costs will be inflated to 2017 values using the relevant consumer price indices from the International Monetary Fund, and converted from local currency units to international dollars using purchasing power parity exchange rates.

Instruments and measurement of health system and patient costs

Patient costs

Information on patients' demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, household assets and MDR-TB-related costs will be collected by administering an adaptation of a validated questionnaire recommended by the Stop TB partnership.17 18 Patient costs will include out-of-pocket healthcare costs (eg, charges for diagnostic tests, administration fees, expenses associated with hospitalisation); cost of travel to health facility incurred by patients and their guardians; and other related treatment costs (eg, nutrition supplements). To obtain estimates of productivity lost by patients and their caregivers who gave up paid employment, information on their pre-MDR-TB earnings will be collected. Patients will also be asked about coping costs—money they borrowed or received from selling assets to cover the cost of treatment.

Data to estimate patient costs will be collected in two stages. First, through a baseline questionnaire at enrolment to either arm, capturing demographic details such as asset ownership. Second, patient follow-up costs questionnaire every 3 months after enrolment. The questionnaire will include questions on patient and household costs such as fees paid to the health system, drugs and laboratory test costs, transport, food, accommodation costs incurred as a result of the treatment process as well as costs incurred as a result of managing adverse events and time lost from economic activities due to illness or care-seeking. Various measures and sources of patient costs are discussed and summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Description of key categories of patient costs and sources

| Main variable | Description | Information source |

|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment patient socioeconomic status | Education, employment, income, asset ownership and socioeconomic indicators | Baseline questionnaire capturing socioeconomic status of patient before starting treatment |

| Direct and indirect costs | Follow-up checks and tests, hospitalisation, relocation, dietary supplements and treatment of adverse events (including ancillary medicines) | Follow-up questionnaire capturing

|

| Coping | Sources of funding for patient costs, borrowing, sales of assets, leasing of assets | Baseline and follow-up questionnaires capturing coping strategies during diagnosis and treatment periods |

Non-medical direct costs will include home help received as a result of morbidity related to MDR-TB, patient and caregivers time directly related to the intervention (time spent getting to the facility, waiting room and intervention). The patients will be asked to quantify how much work was actually performed during regular hours and quality of this work compared to now.

Health system costs

Information on health systems costs will be collected from various sources. Specifically, we will collect data on resources and costs related to personnel, clinical practice, laboratory tests, drugs and medical supplies. Primary data on these variables will be collected and estimated using information from budget and financial records maintained by health facilities in the study sites and their related health system structures (eg, Ministry of health suboffices or district hospitals). Data on the usage of STREAM trial health services, the associated consumption of drugs and medical supplies and time allocated to STREAM trial care by staff in the study sites will be collected from individual patient records and pharmacy logs and in time allocation interviews with the study site healthcare providers and stored in an electronic database in the context of South Africa, while in Ethiopia, it is captured directly within an Excel spreadsheet developed for the economic evaluation. Unit costs for healthcare resources will be derived from local and national sources and performed in line with best practices.19–23

Various measures of health system cost are discussed and summarised in table 2. Medical direct costs include those attributable to healthcare visits for the treatment of MDR-TB: the cost of training provided to healthcare providers; visits to primary healthcare facilities, to specialists and to rehabilitation services; number of essential tests; cost of medicines and disposable supplies as well as hospitalisation for acute episodes of SAE.

Table 2.

Description of key categories of health systems costs and sources

| Type of cost | Description | Information source |

|---|---|---|

| Labour | Disaggregated into cadre and type at proportion of time spent Staff overheads |

MOH district health office, implementing partners records and staff interviews |

| Transport (Ethiopia only) | Vehicles Fuel Maintenance |

MOH district health office, implementing partners records and staff interviews |

| Capital costs | Equipment Building Computers |

MOH district health office, implementing partners records and staff interviews |

| Supplies | Drugs Personal protective equipment Other supplies |

MOH district health office, implementing partners records and staff interviews |

| Diagnostics | Laboratory tests X-rays ECGs |

Diagnostic firms, MOH offices, implementing partners records and staff interviews |

MOH, Ministry of Health.

Primary data on health system and patient costs will be collected from from South Africa and Ethiopia. For incremental cost analysis purposes, resource use in the control arm will be estimated based on cost of standard care, using information from budget and financial records maintained by the local hospital and their related Ministry of Health (MOH) structures. An ingredients approach will be taken, where the value of inputs is based on quantities and unit prices (the ingredients). Only incremental costs associated with the study regimen will be included.

Staff costs will be obtained through an analysis of health worker time involved in prescribing, monitoring and supervising the study and control regimens at each site. This will be obtained through interviews with health workers involved at different stages in the treatment pathway, including those performing diagnostic and other tests during treatment and during the follow-up period. The cost of this time will be based on salaries and benefits of different health workers involved. Data will be obtained from the MOH based on grade of staff rather than named individuals.

The costs of drugs, laboratory reagents, monitoring stationery, equipment and other consumables will be collected from study, health facility or Ministry of Health (MOH) records, according to the procurement source. Where possible actual costs will be used; these will be adjusted for standard or market rates where study-related discounts or additional costs have been incurred. The costs of all diagnostic and follow-up tests will be collected during the study. Equipment will be depreciated over the expected life of the item. For example, 3 years for computing equipment and 5 years for diagnostic equipment. In all cases, a literature search will inform the most common choices for selected depreciation rates.12 Costs that are incurred over >1 year will be discounted at the rate of 3% per annum.12 19–23

Only costs associated with implementation will be included; any costs that are clearly necessary only for study purposes (such as nurse time allocated to administration of cost questionnaires) and not for routine practice will be excluded from the analysis. The effect of including costs that were incurred for research trial monitoring (such as intensive Holter ECG monitoring), but may or may not be necessary for implementation will be assessed through sensitivity analyses. Costs will be analysed into one-time costs required for establishing the study regimen and recurrent costs for sustaining the study regimen. Data will be collected from at least two study sites in each country (unless only one site is used). Where possible, these will have different characteristics (eg, secondary/tertiary facility; urban/rural).

Considering that medicines used in clinical trials and practice may often have SAE which could lead to considerable economic and clinical costs, the study will also collect costs related to SAE. Costs for SAE will be estimated using case reference forms, case notes and receipts from diagnostic suppliers and hospital records.

Data analysis

Costs will be analysed using excel and an operational model. The evaluation will include using patient pathway models to understand the impacts on costs and delays of any lack of adherence to stated diagnostic and treatment policy. This approach will provide additional information to inform the development of policies, guidelines and the cost-effectiveness analysis. The model will combine information derived from the documented patient pathways, clinical data and cost information. This operational model will be built using discrete event simulation following the approach previously used in Tanzania to assist policy decisions on TB diagnostics.24

Uncertainty in the estimated costs due to uncertainty to cost input parameter values will be evaluated by employing probabilistic sensitivity analysis using the lower and upper bound of CIs. Specifically, sensitivity analyses will be undertaken on the basis of price and activity fluctuations, informed by time required to complete various activities in the patient pathways using the operation model. Given the problem of using a controlled trial to estimate real-world costs (the trial almost inevitably invests more in adherence to regimen, eg, than will be performed in practice), sensitivity analysis will be crucial as this has implications for treatment outcomes and costs.

Patient costs will be analysed in total and by subcategory of cost (eg, medical expenses, transport) for patients on each study regimen. Given that patient treatment costs are typically positively skewed (not normally distributed), the distribution of patient costs will be assessed in each country. If the costs are not normally distributed, log transformations will first be performed to see whether this creates a normal distribution, and if not, non-parametric tests will form the basis for the analysis. While every effort will be made to ensure complete data collection, missing data due to loss to follow-up, unwillingness to provide economic data or inaccurate/incomplete completion of forms are always a possibility. The nature and pattern of any such ‘missingness' will be carefully considered—including in particular whether data can be treated as ‘missing at random’. If it is seen as appropriate, values for missing items will be imputed using multiple imputation routines commonly available in standard software packages.

Further analyses will disaggregate cost by socioeconomic status and by gender of patient. Costs will be compared with the income level of the patients for each level of socioeconomic status. Depending on availability, information on socioeconomic indicators will be obtained from either local household budget survey data or Lifestyle Monitoring Survey Data.12 19–23

Discussion

This study seeks to address an important problem related to MDR-TB which is more costly to treat compared to drug-susceptible TB with financial implication on the health system and patients. There is a need for improvement in the diagnosis, treatment and management of MDR-TB. This study will provide evidence on the resources and costs related to treatment and management of patients with MDR-TB using the short regimen when compared to the WHO MDR-TB treatment regimen and assist in policy development.

Ethical approval

The trial has received ethical approval from the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (approval number 07/11) and from the ethics committees of each of the participating sites, namely: South African Medical Research Ethics Committee (approval number EC011-8/2011), Wits Health Consortium Protocol Review Committee (approval number 110602), University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol 130978), University of Kwazulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC REF BFC076B/11), St Peter TB Specialized Hospital Ethical Review Committee; Addis Ababa and AHRI-ALERT Ethical Review Committee, Addis Ababa (approval number PO 23/11).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Elena Gospodarevskaya for her involvement in the early stages of the design of the study and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union North America) for providing funding and technical support.

Footnotes

Contributors: SBS and EG outlined the original design of this economic study. EG drafted the protocol and contributed to the design of the study. JM and IL contributed to the design of the study and the drafting of the protocol. MG, DE and SR contributed to the drafting of the protocol. SBS acted as study guarantor and contributed to the further elaboration of the study design and the drafting of the protocol.

Funding: The primary funder of the trial is the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Cooperative Agreement GHN-A-00-08-00004-00. Additional funding was provided by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council (MRC) and the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement.

Disclaimer: This document has been produced thanks to a grant from USAID. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and under no circumstance be regarded as reflecting the position of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union North America) nor those of its Donors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Aikins AG, Unwin N, Agyemang C et al. Tackling Africa's chronic disease burden: from the local to the global. Global Health 2010;6:5 10.1186/1744-8603-6-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global alliance against chronic respiratory disease (GARD), General assembly meeting report Geneva: WHO, 2013. http://www.who.int/gard/publications/GARDGMreport2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global tuberculosis report 2015 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (accessed 22 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kankeu HT, Saksana P, Xu K et al. The financial burden from non-communicable disease in low-and middle-income countries: a literature review. Health Res Policy Syst 2013;11:31 http://www.health-policy-systems.com/content/11/1/31 10.1186/1478-4505-11-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzpatrick C, Floyd K. A systematic review of the cost and cost effectiveness of treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Pharmacoeconomics 2012;30:63–80. 10.2165/11595340-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnippel K, Rosen S, Shearer K et al. Costs of inpatient treatment for multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2013;18:109–16. 10.1111/tmi.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanimura T, Jaramillo E, Weil D et al. Financial burden for tuberculosis patients in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Eur Respir J 2014;43:1763–75. 10.1183/09031936.00193413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Deun A, Maug AKJ, Salim MAH et al. Short, highly effective and inexpensive standardized treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:684–92. 10.1164/rccm.201001-0077OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanciole AE, Ortegón M, Chisholm D et al. Cost effectiveness of strategies to combat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma in sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia: mathematical modelling study. BMJ 2012;344:e608 10.1136/bmj.e608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van den Boom M, Seita A, Ottmani S et al. Finding the way through the respiratory symptoms jungle: PAL can help. Eur Respir J 2010;36:979–82. 10.1183/09031936.00116810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gospodarevskaya E, Tulloch O, Bunga C et al. Patient costs during tuberculosis treatment in Bangladesh and Tanzania: the potential of shorter regimens. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014;18:810–17. 10.5588/ijtld.13.0391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drummond M, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publication, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunn AJ, Rusen ID, Van Deun A et al. Evaluation of a standardized treatment regimen of anti-tuberculosis drugs for patients with Multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (STREAM): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:353 10.1186/1745-6215-15-353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins D, Beyene D, Tedla Y et al. Costs faced by multi-drug resistant tuberculosis patients during diagnosis and treatment Report from a pilot study in Ethiopia. TB CARE I—Management Sciences for Health, 2013. http://www.msh.org/sites/msh.org/files/costs_faced_by_mdr_tb_patients_-_ethiopia.pdf (accessed 25 Jun 2015).

- 15.Knox S. Sample calculation in economic evaluation, Cancer Research Economics Support Team (CREST), 2012. http://www.crest.uts.edu.au/pdfs/Factsheet-Sample_Size_in_EE-FINAL.pdf

- 16.WHO. Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis, 2011. who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44597/1/9789241501583_eng.pdf

- 17.Kemp JR, Mann G, Simwaka BN et al. Can Malawi's poor afford free tuberculosis services? Patient and household costs associated with a tuberculosis diagnosis in Lilongwe. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:580–5. 10.2471/BLT.06.033167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Tuberculosis Coalition for Technical Assistance, KNCV Tuberculosis Foundation, WHO, Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association, USAID. The tool to estimate patients’ costs. Washington: (DC: ): TBCTA, 2008. http://www.stoptb.org/ Wg/dots_expansion/tbandpoverty/assets/documents/Tool to estimate Patients’ Costs.pdf (accessed 13 Mar 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Tsuchiya A et al. Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drummond M, McGuire A. Economic evaluation in health care, merging theory and practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnard SS et al. Economic evaluations in clinical trials. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publication, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker DG, Aedo C, Albala C et al. Methods for economic evaluation of factorial-design cluster randomised controlled trial of a nutrition supplement and an exercise programme among healthy older people living in Santiago, Chile: the CENEX study. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:85 10.1186/1472-6963-9-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeFevre AE, Shillcutt SD, Waters HR et al. Economic evaluation of neonatal care packages in a cluster-randomised controlled trial in Sylhet, Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:736–45. 10.2471/BLT.12.117127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langley I, Lin H, Egwaga S et al. Assessment of the patient, health system, and population effects of Xpert MTB/RIF and alternative diagnostics for tuberculosis in Tanzania: an integrated modelling approach. Lancet Global Health 2014;2:e581–91. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70291-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]