Abstract

A previously healthy 66-year-old woman living in the Mid-Atlantic USA presented to the hospital with lethargy, ataxia and slurred speech. 2 weeks prior she had removed a tick from her right groin. She reported malaise, fevers, diarrhoea, cough and a rash. Physical examination revealed a maculopapular rash on her chest, and lung auscultation revealed bi-basilar rales. Laboratory tests were remarkable for hyponatraemia, leucopenia and thrombocytopenia. Chest X-ray demonstrated bilateral pleural effusions with pulmonary oedema. She was treated with ceftriaxone and azithromycin for possible community-acquired pneumonia but declining mental status necessitated intensive care unit transfer. Vancomycin and doxycycline were added. Her course was complicated by seizures requiring antiepileptic therapy. Peripheral blood smear demonstrated morulae in monocytes. Serum Ehrlichia chaffeensis DNA was positive confirming the diagnosis of human monocytic ehrlichiosis. She recovered without residual neurological deficits after 10 days of doxycycline therapy.

Background

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) is the most common life-threatening tick-borne illness in the USA.1 The overall fatality rate of HME has been reported to range from 3% to 5%.2 We report a case of a 66-year-old woman with HME who presented with severe neurological symptoms including tonic–clonic seizures as well as multiorgan failure. Remarkably the patient made a complete recovery after treatment with doxycycline.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old woman presented to the hospital with malaise, fevers and chills, diarrhoea, cough, and a rash.

The patient had been well until ∼5 days prior to her presentation when she was noted by her husband to have slurred speech, accompanied by gradually worsening fatigue and fevers. Additional symptoms included generalised joints pain, most pronounced in the elbow and knee joints as well as a faint rash along the eyelids, anterior neck, chest, abdomen and legs. She noted fevers up to 39.3°C (102.7°F) at home. She took multiple doses of naproxen and acetaminophen without any symptom relief.

Two days prior to admission she reported a constant, throbbing headache. She felt unsteady on her feet and started requiring assistance while walking. She also developed diarrhoea that was associated with mild abdominal pain, a decrease in appetite, as well as a mild cough with scant non-bloody sputum production. On the day of admission the rash over her eyelids and anterior neck had started to resolve while the rash on her chest remained noticeably erythematous. She experienced extreme fatigue and she subsequently presented to our institution.

In the emergency room, she reported of fevers and malaise, a constant, throbbing headache, watery diarrhoea up to five times daily and cough with increasing respiratory secretions. She denied nausea, vomiting, haematochezia, melena or dyspnoea. Her medical history was notable for mild osteoarthritis, depression with anxiety and osteoporosis. She had undergone an appendectomy and, due to a family history of ovarian cancer, a prophylactic oophorectomy several years prior to presentation. Her medications included escitalopram and ibandronate. She had no known drug allergies. She lived in a wooded community in a metropolitan area in the Mid-Atlantic USA and was working as a language professor at a local university. She had never used any recreational drugs.

One month before admission, she had travelled to Hawaii and stayed at a resort. She did not recall any unusual activity or exposures during that trip. Two weeks previously, she had removed a tick from her right groin; she had not noticed any redness or tenderness at that time.

On physical examination, the patient was ill appearing in moderate distress and appeared lethargic. Her vital signs included a temperature of 36.7°C (98.1°F) and a blood pressure of 103/67 mm Hg with a heart rate of 77 bpm. Her respiratory rate was 16 respirations/min and her oxygen saturation was 95% on room air. She was alert and oriented to self, time and place. She was able to flex her neck and did not have photophobia. Her speech was dysarthric with word-finding difficulties and occasional inappropriate responses to questions. On examination the patient had injected conjunctiva. She had a prominent V-shaped maculopapular rash on the anterior neck and chest in sun exposed areas. Cardiac examination was normal. Lung auscultation was remarkable for pronounced bi-basilar rales. Abdominal examination was benign. The remainder of the examination was normal.

Initial laboratory studies revealed hyponatraemia (sodium 127 µm/L), leucopenia (leucocyte count 2.5×103 cells/µL, 84% neutrophils, 10% lymphocytes), thrombocytopenia (platelet count 37×103 cells/µL) and elevated liver-associated enzymes (alkaline phosphatase 371 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 619 U/L, alanine transaminase 227 U/L). Prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times were prolonged at 16.1 and 124 s. Fibrinogen was low at 170 mg/dL and C reactive protein was elevated at 205 mg/L. Screening for antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and rheumatoid factor (RF) was negative.

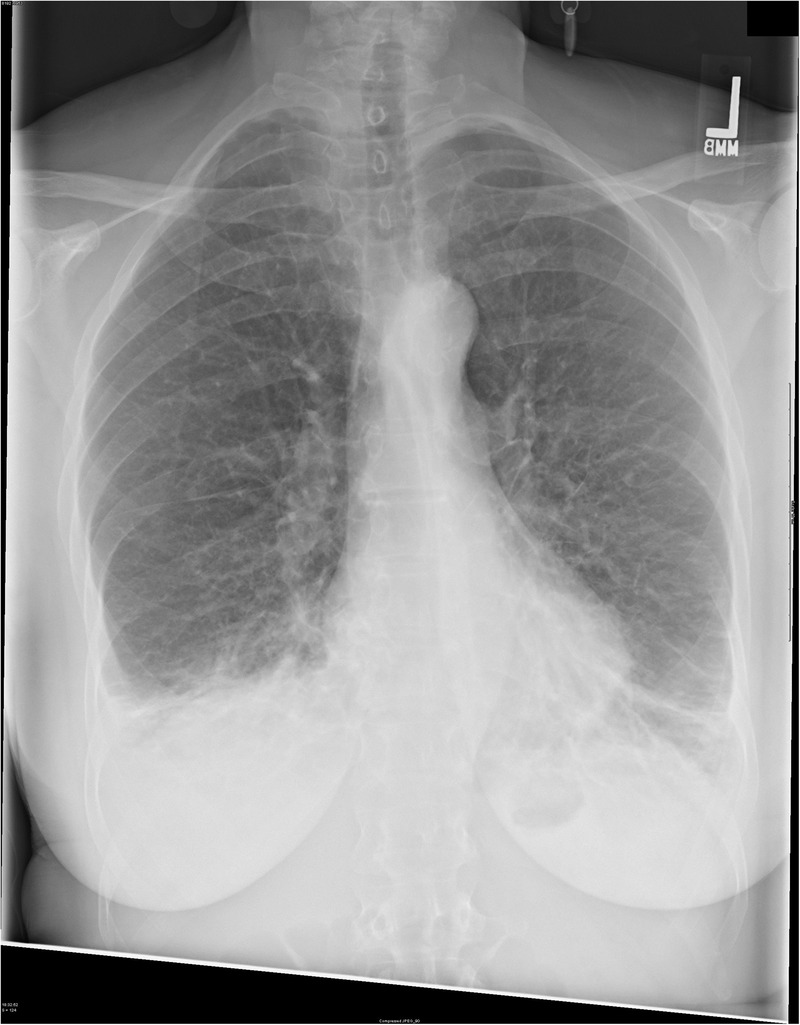

Chest X-ray showed mild pulmonary oedema and small bilateral pleural effusions (figure 1). Non-contrast CT scan of the head showed no acute abnormalities.

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph demonstrating mild interstitial oedema and bilateral pleural effusions.

The patient was empirically started on intravenous azithromycin 500 mg intravenously daily and ceftriaxone 1 g intravenously every 12 hours for presumed community-acquired pneumonia and was admitted to the medical ward. Approximately 12 hours after initial presentation, the patient developed worsening respiratory distress and marked confusion. She was transferred to the intensive care unit where vancomycin 500 mg intravenously every 6 hours was empirically added to her antibiotic regimen. Owing to deterioration in her mental status, the ceftriaxone dose was increased to 2 g intravenously every 12 hours. Azithromycin was discontinued.

Around 38 hours into her hospitalisation, she experienced generalised tonic–clonic seizures, which were treated with intravenous lorazepam and levetiracetam. Given her thrombocytopenia, a lumbar puncture (LP) was not performed. The patient was seen by the infectious diseases consult service who immediately recommended to start intravenous doxycycline 100 mg intravenously every 12 hours due to their concern for a tick-borne infection.

Investigations

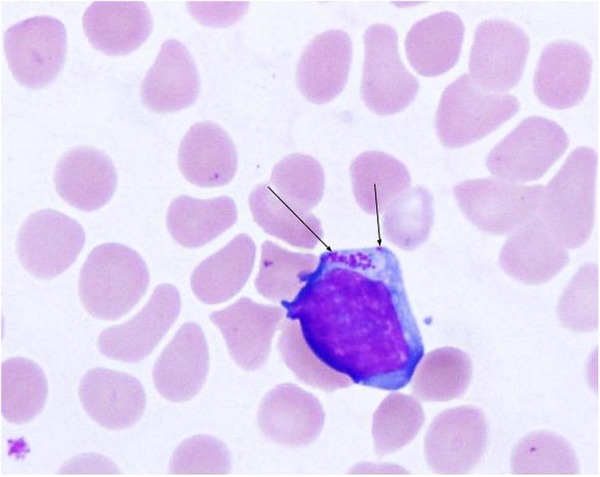

A Wright-Giemsa stain of the patient's peripheral blood smear demonstrated intramonocytic morulae (figure 2). Serum Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum PCR, Babesia PCR and Borrelia burgdorferi serologies were ordered.

Figure 2.

Wright-Giemsa peripheral smear demonstrates cytoplasmic Ehrlichia morulae in a monocyte (arrows).

Differential diagnosis

The patient's initial presentation was remarkable for fevers, mental status changes associated with seizures, leucopenia, elevation of liver-associated enzymes and marked thrombocytopenia. Despite broad-spectrum antibiotics she experienced progressive respiratory failure, deterioration of mental status with eventual development of seizures.

Abnormalities affecting multiple organ systems in a previously healthy individual strongly suggest a primarily systemic process such as a rheumatological, haematological or infectious disease. Somewhat less likely, a life-threatening process affecting a single organ system (eg, respiratory, neurological or gastrointestinal) with secondary systemic effects (eg, through sepsis, impairment of central nervous system (CNS) function or DIC) must be considered.

Rheumatological

Severe autoimmune conditions that can cause systemic illness with dominant CNS changes include neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NPSLE). Although the initial presentation of NPSLE occurs in women of reproductive age,3 12–18% of patients present after the age of 50.4 Overlap with other autoimmune conditions such as antisynthetase syndrome is not uncommon and would be consistent with findings of arthralgias and characteristic rashes the patient presented with. However, ANA were absent in this patient, as was RF. In the setting of negative ANA and RF, symptoms of fevers, rash, generalised joints pain with markedly elevated ferritin levels (>10 000 U/L) are consistent with adult-onset Still's disease. However, this diagnosis would fail to account for the presence of the remaining findings.

Haematological

Owing to the presence of profound coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia, a primary haematological process such as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) should be considered. However, only mildly decreased fibrinogen levels and the absence of schistocytes make TTP unlikely. Profound elevation of ferritin levels, hypofibrinogenaemia, pancytopenia, fevers is seen in primary or secondary histiocyte hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) although these findings can also be seen secondary to sepsis.

Neurological

Normal CT imaging of the head excluded structural causes of neurological impairment such as a brain abscess or mass. These causes would also fail to explain multiorgan failure.

Gastrointestinal

Given the markedly elevated liver enzymes, coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia, testing for causes of hepatitis was pursued. This demonstrated negative testing for viral hepatitis including hepatitis A/B/C and cytomegalovirus/Epstein-Barr virus. Serum levels for common hepatotoxins such as paracetamol were also undetectable.

Infectious

Cough, fever and sputum as well as presence of pleural effusions make an initial concern for community-acquired pneumonia understandable. However, her progressive decline despite broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy strongly argues against this diagnosis.

A febrile illness with a history of a recent tick bite in an endemic area raises a strong suspicion for tick-borne disease, such as ehrlichiosis, anaplasmosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), babesiosis or Lyme disease. A peripheral smear demonstrated morulae in monocytes suggestive of HME. E. chaffeensis was identified by PCR of the patient's blood, confirming the diagnosis of HME. The severity of her presentation raises concern for coinfection with diseases that share the Ixodes scapularis tick as a vector, such as Lyme disease or babesiosis, but testing for these pathogens was negative.

Treatment

The patient was treated for severe HME with neurological involvement with a 10-day course of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily given intravenously for the first 4 days until the patient was alert enough to tolerate taking this orally. All other antibiotics were stopped within 48 hours of the doxycycline having been started.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient made a full recovery without any residual neurological deficits and has resumed teaching as a University professor.

Discussion

As with many infectious diseases, HME has a broad spectrum of clinical presentations. The majority of patients present with a non-specific febrile illness following a tick bite. Most patients do not seek medical advice and recover without any specific antimicrobial therapy. Fatal HME that mimics toxic a shock-like syndrome has been reported to occur in about 2–5% of patients.1 2 Risk factors for developing severe disease include age above 50 years and the presence of immunosuppression,4–6 although immunosuppression was not found to be related to outcome in another study.5 Early therapy is a predictor of favourable outcome.6 The causative organisms for Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis and babesiosis can coexist in the same I. scapularis tick, with reported rates of coinfection in ticks ranging from 3% to 15% in Connecticut and Wisconsin7 to up to 28% in some regions of Europe.8 Since endemic areas for I. scapularis and Amblyomma americanum ticks overlap in the USA, testing for other tick-borne infections like RMSF is prudent.

Despite considerable efforts, no specific genotypic difference in Ehrlichia species has been identified in patients with mild and severe disease,9 10 suggesting that host factors rather than the organism itself determine severity of disease. The development of profound shock in patients with only limited numbers of visibly infected cells on peripheral smear has been suggested as evidence that immunological dysregulation by cytokines and other inflammatory mediators may be responsible.9 In a similar vein, HLH secondary to infection with Ehrlichia has been reported.10 Diagnostic criteria for HLH include fever, splenomegaly, hypofibrinogenaemia, as well as hyperferritinaemia, which were met in this patient. Other criteria, that is, low or absent natural killer cell activity, haemophagocytosis in BM, spleen or lymph nodes and low soluble CD25 levels were not tested in this patient. Although a diagnosis of HLH requires at least five criteria, and three tests were not pursued for practical reasons, it is possible that secondary HLH played a role in the severity of her presentation. Interestingly, the idea that the severity of HME is caused by secondary HLH has led some clinicians to use a combination of the interleukin-1 antagonist anakinra and high-dose corticosteroids as adjunct to doxycycline in select patients.11

Neurological findings have been reported in 22% of patients,12 most commonly in the form of photophobia, confusion, hallucinations, stupor, meningitis and coma.12 Seizures, as reported here, are an uncommon feature and occur in only 2.4% of patients.12 In a case series of 14 patients who presented with involvement of the CNS and underwent CT scan of the head, none of the patients had abnormal CT imaging.13 The role of LP remains unclear. In a study of 15 patients with neurological manifestations, cerebrospinal fluid studies showed abnormalities in about 50% of cases, most commonly lymphocytic pleocytosis and elevated protein levels.13 Morulae were only visualised in 1 of the 15 patients. Therefore, LP is not necessary for the diagnosis of severe HME if the presentation strongly suggests ehrlichiosis, particularly in cases with severe thrombocytopenia.

As demonstrated in this case, the non-specific nature of the presentation requires a high clinical index of suspicion for this diagnosis. Despite the availability of PCR and serological testing, treatment is commonly initiated empirically in the setting of a history of tick bite.1 Treatment of choice is doxycycline and, due to excellent oral absorption, oral and intravenous dosing is thought to be equivalent.14 Systematic pharmacokinetic studies have not been performed but reports suggest meningeal penetration of ∼20% which is not affected by the presence or absence of meningitis.15 16 Although rifampin and chloramphenicol have been used as alternative agents, the life-threatening disease should prompt the immediate administration of doxycycline in patients of all ages.17

Learning points.

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) is an infectious disease most commonly caused by the intracellular parasitic organism Ehrlichia chaffeensis.

Neurological manifestations occur in about 20% of cases of HME and include altered mental status, ataxia, severe headache, lethargy and can include seizures.

While imaging studies such as CT scan of head are not usually diagnostic, they play an important role in excluding other causes of severe neurological disease.

Severely ill patients of all ages should be administered doxycycline if tick-borne rickettsial disease is suspected.

With appropriate antibiotic treatment, even patients with severe neurological presentation of HME can be expected to make a full neurological recovery.

Footnotes

Contributors: CG wrote the article and performed the literature search. He is the guarantor. JD and CG had the idea to publish the case. JD identified the case, revised the draft and obtained photographs of the peripheral smear. MS suggested structure and emphasis of the article, provided multiple major revisions of the draft, and managed the case.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ismail N, Bloch KC, McBride JW. Human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis. Clin Lab Med 2010;30:261–92. 10.1016/j.cll.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dumler JS, Bakken JS. Ehrlichial diseases of humans: emerging tick-borne infections. Clin Infect Dis 1995;20:1102–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J et al. . Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. The European Working Party on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore) 1993;72:113–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rovenský J, Tuchynová A. Systemic lupus erythematosus in the elderly. Autoimmun Rev 2008;7:235–9. 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas LD, Hongo I, Bloch KC et al. . Human ehrlichiosis in transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2007;7:1641–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamburg BJ, Storch GA, Micek ST et al. . The importance of early treatment with doxycycline in human ehrlichiosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87:53–60. 10.1097/MD.0b013e318168da1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belongia EA. Epidemiology and impact of coinfections acquired from Ixodes ticks. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2002;2:265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swanson SJ, Neitzel D, Reed KD et al. . Coinfections acquired from Ixodes ticks. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19:708–27. 10.1128/CMR.00011-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ismail N, Walker DH, Ghose P et al. . Immune mediators of protective and pathogenic immune responses in patients with mild and fatal human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis. BMC Immunol 2012;13:26 10.1186/1471-2172-13-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns S, Saylors R, Mian A. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to Ehrlichia chaffeensis infection: a case report. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2010;32:e142–3. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181c80ab9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar N, Goyal J, Goel A et al. . Macrophage activation syndrome secondary to human monocytic ehrlichiosis. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 2014;30(Suppl 1):145–7. 10.1007/s12288-013-0299-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olano JP, Hogrefe W, Seaton B et al. . Clinical manifestations, epidemiology, and laboratory diagnosis of human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis in a commercial laboratory setting. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2003;10:891–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratnasamy N, Everett ED, Roland WE et al. . Central nervous system manifestations of human ehrlichiosis. Clin Infect Dis 1996;23:314–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi N, Miller DQ. Doxycycline revisited. Arch Intern Med 1997;157: 1421–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nau R, Sörgel F, Eiffert H. Penetration of drugs through the blood-cerebrospinal fluid/blood-brain barrier for treatment of central nervous system infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010;23:858–83. 10.1128/CMR.00007-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson M, Hammers S, Nilsson-Ehle I et al. . Concentrations of doxycycline and penicillin G in sera and cerebrospinal fluid of patients treated for neuroborreliosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1996;40:1104–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman AS, Bakken JS, Folk SM et al. . Diagnosis and management of tickborne rickettsial diseases: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrlichioses, and anaplasmosis—United States: a practical guide for physicians and other health-care and public health professionals. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55(RR-4):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]