Abstract

Introduction

Infants born extremely preterm (EP; <28 weeks' gestation) and/or with extremely low birth weight (ELBW; <1000 g birth weight) are at increased risk for adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. However, it is challenging to predict those EP/ELBW infants destined to have long-term neurodevelopmental impairments in order to target early intervention to those in most need. The General Movements Assessment (GMA) in early infancy has high predictive validity for neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants. However, access to a GMA may be limited by geographical constraints and a lack of GMA-trained health professionals. Baby Moves is a smartphone application (app) developed for caregivers to video and upload their infant's general movements to be scored remotely by a certified GMA assessor. The aim of this study is to determine the predictive ability of using the GMA via the Baby Moves app for neurodevelopmental impairment in infants born EP/ELBW.

Methods and analysis

This prospective cohort study will recruit infants born EP/ELBW across the state of Victoria, Australia in 2016 and 2017. A control group of normal birth weight (>2500 g birth weight), term-born (≥37 weeks' gestation) infants will also be recruited as a local reference group. Parents will video their infant's general movements at two time points between 3 and 4 months' corrected age using the Baby Moves app. Videos will be scored by certified GMA assessors and classified as normal or abnormal. Parental satisfaction using the Baby Moves app will be assessed via survey. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years' corrected age includes developmental delay according to the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development-III and cerebral palsy diagnosis.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by the Human Research and Ethics Committees at the Royal Children's Hospital, The Royal Women's Hospital, Monash Health and Mercy Health in Melbourne, Australia. Study findings will be disseminated via peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.

Keywords: extremely preterm, extremely low birth weight, General Movements Assessments, Cerebral Palsy, Smart Phone Application

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strengths of this study include the use of an app, called Baby Moves, to assist in early detection of cerebral palsy (CP) and other neurodevelopmental outcomes in a geographical cohort.

The Baby Moves app provides a format for accessing general movements (GMs), which is not limited by geographical distance or clinicians' skill levels at a local service, as users will be able to upload the infant's GMs directly to a trained assessor.

Diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental impairment, such as CP, is a complex process and while we expect that the app will facilitate identification of infants at high risk of CP and/or other neurodevelopmental impairments, it cannot be used alone as a diagnostic tool.

If the Baby Moves app is shown to be effective in early detection, future studies involving other developed countries along with developing countries will be needed.

Background

Infants born extremely preterm (EP, <28 weeks' gestation) and/or with extremely low birth weight (ELBW, <1000 g birth weight) are at high risk of neurodevelopmental impairment, such as cerebral palsy (CP).1 CP is one of the most common physical disabilities of childhood and while the causal pathways are multifactorial, the brain injury responsible for CP primarily arises during the prenatal/perinatal period (94.4% of cases).2 There is a disproportionate number of preterm children with CP compared with term-born children; for example, while children born preterm account for 8% of the Australian population, ∼40% of children with CP on the Australian CP register are born preterm, with the risk of CP for preterm infants greatest for those born EP.2 3 Furthermore, infants born EP/ELBW have increased risk of other neurodevelopmental impairments with recent research demonstrating that 47% had impairments across more than one developmental domain at school age and higher rates of motor impairment.4 5

There is a growing body of evidence that early intervention improves functional outcomes for infants with neurodevelopmental impairment and is economically cost-effective as it reduces the rate of later problems.6 7 Early detection of neurodevelopmental impairment is therefore crucial to ensuring timely referral to early intervention given that limited resources result in stringent eligibility criteria and long waiting lists for services.

However, it is challenging for clinicians to identify those infants who are at highest risk for neurodevelopmental impairment, and this can delay access to early intervention during a crucial period of brain plasticity and musculoskeletal development. Research in an Australian context has demonstrated that almost 50% of preterm children with moderate-to-severe disabilities were not receiving early intervention services at age 2 years with families with greater social disadvantage less likely to access services.8

Neurodevelopmental assessments that can identify those at highest risk for adverse neurodevelopment during early infancy are therefore vital for clinicians to target early intervention and counsel parents. Studies in very preterm infants (<32 weeks' gestation) have demonstrated that infants with neurodevelopmental impairment show signs of movement abnormalities as early as 1 month of age.9 Importantly, Prechtl's method of assessment of the quality of general movements, known as GMA, can accurately predict those children most at risk of neurodevelopmental impairment when used in the first few months of life.10 11 General movements (GMs) are defined as spontaneous movements involving the whole body with a changing sequence of arm, leg, neck and trunk movements varying in amplitude and speed.12 GMs are present in early fetal life up until about 20 weeks' post-term when they are superseded by the infant's goal-directed, voluntary movements.13 GMs have age-specific developmental characteristics: around term age (36–38 weeks' postmenstrual age), GMs are described as ‘writhing’ movements that are elliptical in form, and at 6–9 weeks' post-term GMs gradually change in character to continuous small movements with moderate speed and variable acceleration, called ‘fidgety’ GMs.13 The GMA involves observing these specific spontaneous movements, and assessment is based on a gestalt perception of the global quality of the infant's movement, without requiring any handling or direct interaction with the infant.13 Systematic reviews have consistently highlighted the predictive validity of the GMA for neurodevelopmental impairment, including CP and its clinical utility.11 14 A recent systematic review established that GMs were the best predictor of CP with summary estimates of sensitivity and specificity of 98% (95% CI 74% to 100%) and 91% (95% CI 83% to 93%), respectively, in comparison with cranial ultrasound which had sensitivity 74% (95% CI 63% to 83%) and specificity 92% (95% CI 81% to 96%), and with neurological examination which had sensitivity 88% (95% CI 55% to 97%) and specificity 87% (95% CI 57% to 97%), respectively.11

The highest predictive value for the GMA is at 3 months' post-term when fidgety GMs are typically at their most prominent.15 However, many EP/ELBW follow-up clinics do not offer GMA at this age due to the costs involved in delivering outpatient services, distance required for families to travel or lack of staff with the GMA certification required to score the assessment. Given that the GMs can be assessed from a short video, with no specific handling needed, it is possible to score the GMA off-site. Therefore, we have developed a smartphone application (app), called Baby Moves, so that parents can directly upload a video of their infant's GMs to be assessed by a clinician or researcher trained in the GMA. As such, the Baby Moves app provides access to a GMA for parents of high-risk infants without the need for attending an on-site appointment. Further, the results of the GMA can be communicated with the parents via their managing clinical team with no additional requirement to introduce the infant to another professional.

With advances in technology and mobile communications, smartphones are increasingly viewed as handheld computers rather than phones, due to their powerful on-board computing capability, capacious memories, large screens and open operating systems that encourage application development.16 The popularity of mobile technologies has led to high and increasing ownership of mobile technologies, which means apps can be made available to large numbers of people. There is increasing evidence that smartphone apps have the ability to transform healthcare, improving access to clinical diagnosis and interventions, especially in resource-poor settings.17 A recent systematic review of controlled trials of mobile technology interventions to improve healthcare delivery processes highlighted features that give mobile phones the advantage over other information and communication technologies, including portability, continuous uninterrupted data stream and the capability through sufficient computing power to support multimedia software applications, while significant economic benefits have also been reported where mobile communication is employed in the provision of remote healthcare advice and telemedicine.18 The review, which included 42 studies, concluded that there may be modest benefits in outcomes regarding correct clinical diagnosis and management delivered via app software. However, none of the studies were of high quality; no studies had a low risk of bias and there were none that reported objective clinical outcomes. Therefore, given the potential of smartphone apps to facilitate the early detection of neurodevelopmental impairments, such as CP in high-risk infants, a high-quality research trial is needed to determine whether an app, such as Baby Moves, using the GMA, is useful for the accurate early identification of infants at risk for CP and other neurodevelopmental impairments.

The Baby Moves app

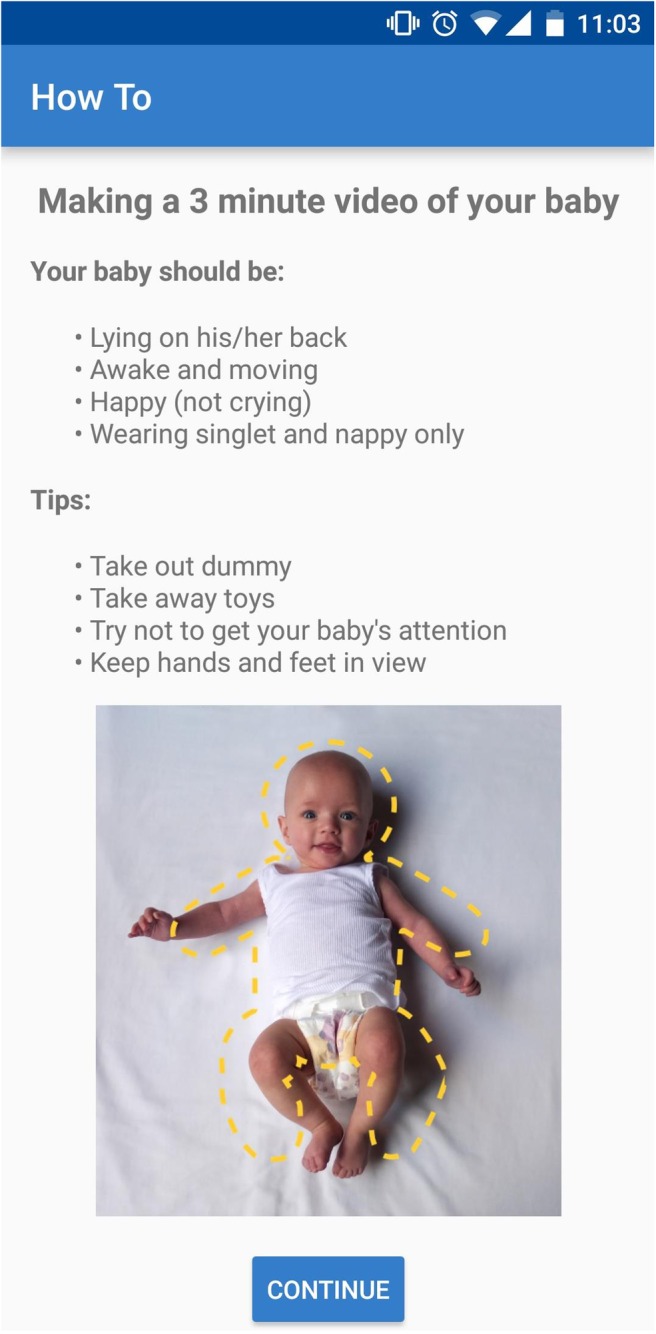

The Baby Moves app is designed for the caregiver (eg, parent) to record a video of their infant's GMs for remote assessment by a scorer trained in the GMA. Parents upload a video of their infant's GMs to a secure server to be assessed by a health professional with GMA certification. The app involves the caregiver entering a unique study number (de-identified) with their infant's date of birth and expected date of delivery. Based on the infant's date of birth, the app provides three automatic reminders at 12 and 14 weeks' corrected age, for parents to record their infant's GMs until these have been uploaded. GMs cannot be recorded outside of these time points to ensure that fidgety GMs are captured at specific ages (time point 1: 12+1 to 13+6 weeks and time point 2: 14+1 to 17+6 weeks). Prior to videoing their infant, the app provides brief instructions on obtaining usable GMs, and an overlay shape provides guidance to optimal positioning to ensure that the infant's entire body is included in the video (see figure 1). GMs are recorded for 3 min only, and parents have the option to either upload the video, or re-record if they are not satisfied with the quality of the initial attempt. Videos are then uploaded to a REDCap database at the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute for scoring. The app then lets the user know when the video has been uploaded successfully.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of information page for the Baby Moves Smartphone app.

Baby Moves has been developed for use on both iPhone (iOS 7.0/8.0/9.0) and Android operating systems (V.4.2–5.1). Key features of the Baby Moves app include notifications to caregivers about the timing of the assessment based on the infant's estimated date of delivery, prompts to instruct caregivers on the correct technique to acquire usable footage (eg, the infant needs to be supine with no stimulation) and specific functionality for multiple births given the high rates of multiple births in the preterm population.

Project overview

This prospective study will describe the neurodevelopmental outcome of infants born EP/ELBW at 2 years' corrected age in a population-based cohort. This study is being conducted by the Victorian Infant Collaborative Study (VICS) group, an initiative since the 1970s that has followed the development of infants born EP/ELBW throughout the state of Victoria, Australia.19 There have been five previous VICS cohorts (1979–1980, 1985–1987, 1991–1992, 1997 and 2005) with detailed perinatal, childhood and for some earlier cohorts, young adult health and neuropsychological assessments, which have allowed the impact of perinatal and neonatal care over time on developmental outcomes for those born EP/ELPBW to be evaluated. The predictive validity of the Baby Moves app, using the GMA, will be examined in EP/ELBW and term-born infants for predicting neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years.

Aims

The main aim of the study is to determine whether using the GMA via the Baby Moves smartphone app is able to identify EP/ELBW infants at high risk of neurodevelopmental impairment, including CP. It is hypothesised that assessing infants with the GMA via the Baby Moves app will have the same predictive value as traditional GMA. The systematic review of Bosanquet et al11 demonstrated that traditional GMA at the age of fidgety GMs have sensitivity and specificity in infants born preterm of 87–100% and 82–95% and 94.4% and 82.5% in the term infant for CP. Other systematic reviews have reported the predictive validity of fidgety GMs as ≥92% sensitivity and ≥82% specificity for neurodevelopmental outcome at 12 and 24 months15 and 42–99% sensitivity and 58–88% specificity for cognitive outcomes.20

A secondary aim of the study is to examine the functionality and utility of the app including parent satisfaction using the Baby Moves app to record their infant's GMs for remote GMA, and the percentage of GMs videos obtained that can be scored. It is hypothesised that the app will have excellent utility: parents of EP/ELBW infants will find the Baby Moves app easy to use and a straightforward way to obtain information about their infant's early neurodevelopment, and the videos uploaded to the server will be scorable.

Methods

Design

Prospective observational cohort study.

Study population

Infants from the Baby Moves study will be recruited as part of the Victorian Infant Collaborative Study (VICS) 2016–2017 cohort.

EP or ELBW infants

All live-born infants born EP (gestational age <28 weeks) and/or ELBW (birth weight <1000 g) in the state of Victoria, Australia during the 12 calendar months from 1 April 2016 to 31 March 2017. Gestational age will be determined using the best obstetric estimate if available, that is, fetal ultrasound conducted before 20 weeks. Cross-checking for verification of the number of live births will be carried out using multiple data sources (the four level-III neonatal intensive care units in Victoria, the Paediatric Infant Perinatal Emergency Retrieval service and the Victorian Perinatal Data Collection Unit).

Normal birth weight term-born infants

Normal birth weight (NBW) term-born controls will be randomly selected (birth weight ≥2500 g and gestation at birth ≥37 weeks) from maternity units affiliated with the level-III perinatal centres, matched with the EP/ELBW survivors according to expected date of birth, the mother's health insurance status (private or public, as a proxy for social class), the main language spoken in her country of birth (English or other) and the child's sex. Control children will be excluded if they receive resuscitation at birth, require admission to neonatal intensive care or if they are identified to have a condition that would affect later neurodevelopment, such as a chromosomal anomaly.

Exclusion criteria

Live births resulting from termination of pregnancy secondary to lethal abnormalities.

Recruitment

Eligible infants will be recruited from the neonatal units and the postnatal wards of the tertiary perinatal centres in Victoria, Australia. A research coordinator will approach parents of eligible infants prior to discharge home or transfer to a neonatal unit at a lower level hospital. The research coordinator will explain the study, including the time commitment, and provide written information about the study. If parent/s agree to be in the study, written consent will be obtained.

Perinatal data collection/baseline data collection

Following recruitment, research nurses will collect data from the medical records regarding maternal medical complications and treatment such as preeclampsia, antenatal corticosteroids and significant medical conditions (eg, diabetes mellitus and epilepsy). Data will also be collected regarding perinatal events that reflect complications during labour and delivery, (eg, antepartum haemorrhage) and neonatal medical complications including bronchopulmonary dysplasia, postnatal corticosteroid treatment, major brain injury, infection and neonatal surgery. Sociodemographic information about employment, family income and parent educational level will also be collected via interview and questionnaire (see online supplementary 1).

bmjopen-2016-013446supp1.pdf (64.8KB, pdf)

GM assessment using the Baby Moves app

When participants are recruited, the researcher will enter the infant's identification number and date of birth into the database so that uploaded videos are linked to a specific identification number within the REDCap database. Parents will then download the app, select and enter in their infant(s) identification number(s), date of birth and estimated date of delivery. GMs will be videoed by parents using the Baby Moves app at 12 and 14 weeks' CA. Two videos are being recorded to ensure that age-specific (fidgety) GMs can be observed according to the individual infant's development. All video data will be stored on secure servers at the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute.

Each video will be scored by two GMA certified assessors independent of each other and who are unaware of the participant's gestation at birth and neonatal history. GMs will be scored according to Prechtl's GMA and categorised as normal if fidgety GMs are intermittently or continuously present, absent if fidgety GMs are not observed or are sporadically present, or abnormal if fidgety GMs are exaggerated in speed and amplitude. If there is a disagreement between the two assessors, then a third experienced assessor and GMs trainer (AJS or CE) will make the final decision.

GMs will be considered scorable if the infant is positioned in supine, is in an active behavioural state, the infant's whole body can be viewed and the recording is of adequate quality. Criteria for scorable and unscorable GMs are outlined in table 1.

Table 1.

Scorable versus non-scorable general movements

| Scorable general movements | Non-scorable general movements |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parents will be contacted within 2 weeks of the second video being uploaded for feedback about their infant's GMs. If an infant has an abnormal GMA, it will be recommended that the infant has an objective, standardised neurological examination and motor assessment as an outpatient. Parents will also be asked to complete a brief online survey about their experience using the app. The survey will include questions about the usability of the app, whether there were any issues uploading the video to the database and parent perception of using the Baby Moves app for a remote GMA rather than a face-to-face visit to a health professional (see online supplement 2).

bmjopen-2016-013446supp2.pdf (66.2KB, pdf)

Neurodevelopmental assessment at 2 years' corrected age

At 2 years' CA, all families will be invited to return for a neurodevelopmental assessment for their child at the admitting tertiary hospital. If the child is unable to attend the hospital, a home visit will be offered. The assessment will be conducted by researchers who are unaware of the child's gestation at birth, perinatal course and previous GMA findings. A paediatrician will perform a standardised neurological evaluation to assess the quality of motor skills, coordination and gait. One of three experienced paediatricians (over 10 years’ experience) will classify the child as having CP based on the clinical examination including abnormal tone and motor function, along with a clinical interview with the parent and exclusion of other causes of motor dysfunction. For cases where CP has already been diagnosed by 24 months, as expected in the majority of extremely preterm children with CP,21 the paediatrician will confirm the diagnosis and its severity. CP will be described using standard criteria, including topography (unilateral vs bilateral), motor type (spastic vs non-spastic) and functional outcomes using the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS).22 Children will also be assessed for neurosensory impairment, including blindness and deafness, with a composite outcome defined as previously published.19 The medical assessment will also involve a review of the child's medical and developmental history, including illnesses (eg, respiratory, neurological, gastrointestinal), surgery, hospital admissions, medication and health services accessed.

Cognitive, language and motor development will be assessed using the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (Bayley-III).23 Cognitive scores and composite scores for the language and motor domains will be calculated. Developmental delay will be defined using scores from either the cognitive or language composite scores from the Bayley-III, with cut-offs compared relative to the mean and SD scores for the controls on the respective scores.19 Developmental delay will be defined as mild (−2 SD to <−1 SD), moderate (−3 SD to <−2 SD) or severe (<−3 SD). Children unable to complete psychological testing because of presumed severe developmental delay will be assigned a score of −4 SD.

A summary report of the 2-year developmental assessment will be sent to families. If there are any additional concerns identified during the assessment that families were previously unaware of, researchers will provide feedback to families and will refer the child to appropriate services, with parental consent.

A description of the neurodevelopmental assessments and the study schedule is summarised in tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Description and purpose of neurodevelopmental assessments

| Assessment | Purpose |

|---|---|

| General Movements Assessment (GMA)13 | Prechtl's assessment of General Movements assesses globally neurological development from birth to 4 months post-term age. It involves observation of specific spontaneous movements and is scored from a video recording. The GMA has excellent psychometric properties, including high predictive validity for neurodevelopmental outcome in preterm infants and excellent inter-rater reliability. |

| Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (Bayley-III)23 | The Bayley-III is a norm-referenced assessment of cognitive, language and motor development that can be used from 1 to 42 months of age. It has good psychometric qualities and has been extensively used in preterm follow-up studies with local norm reference information available. |

| Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS)22 | The GMFCS is a five-level classification system of gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy based on functional abilities, the need for assistive technology and quality of movement. |

Table 3.

Study schedule

| Data collected/ assessment | Corrected age at assessment |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12–14 weeks | 2 years | |

| Perinatal and maternal data | x | ||

| Sociodemographic data | x | ||

| GMA | x | ||

| Baby Moves questionnaire | x | ||

| Bayley-III | x | ||

| Medical assessment | x | ||

| GMFCS | x | ||

Bayley-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development 3rd Edition; GMA, General Movements Assessment; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System.

Data collection and analysis

Sample size

On the basis of data from the most recent Victorian perinatal registry (2010–2011), we anticipate that there will be ∼250 EP/ELBW survivors to 2 years of age in 2016. The equivalent numbers for earlier cohorts were 298 (149 per year) in 1991–1992, 200 in 1997 and 220 in 2005. An equal number of matched term born controls will be recruited over the same time period from 1 April 2016 to 31 March 2017.

Statistical analysis

Data will be analysed according to the aims of the study. The predictive validity of the GMA recorded using the Baby Moves app for CP (primary outcome) and delayed cognitive, language and motor domains will be examined using logistic regression with 95% CIs. All regression analyses will be fitted using generalised estimating equations with robust (sandwich) estimation of SEs to account for clustering due to multiple births. Further, sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values will be determined with 95% CIs. Infants who were not assessed via the Baby Moves app will not be included in this analysis.

To assess parent experience using the Baby Moves app, survey data will be analysed regarding how easy the app was to use, how useful reminders were, and any feedback on changes that are recommended to the app. Data will also be collected on the number of GMs obtained and the percentage of GMs that can be scored versus not scored according to the criteria in table 1. The number of families who do not have access to a smartphone and those who subsequently submit a video via USB or elect to have a face-to-face appointment will be noted. These families will not be required to complete the survey or be included in the analysis of scorable versus non-scorable GMA.

Ethics and dissemination

All study data will be stored in a secure manner. Paper files will be kept in locked filing cabinets and computer and video files will be stored on password-protected servers. Identifiable information (ie, contact and consent details) will be stored in locked filing cabinets separately from other information collected. Only the researchers associated with the study and ethics committees will have access to the data. Video recordings will be stored as digital files on password-protected servers with study identification numbers only.

The researchers will monitor the cohort for any infant deaths. The details of deceased infants will be removed from the database so that parents do not receive notifications from the Baby Moves app after their infant has passed away. If parents do not have smartphone access, they will be offered other options for GMA, including sending in a video of their infant using a prepaid envelope and USB provided by the researchers, or a face-to-face assessment at home or a hospital visit according to their preference. Infants identified with neurodevelopmental concerns at any time point during the study will be referred to appropriate intervention services with parental consent.

The results from the study will be submitted to peer-reviewed journals, as well as presented at national and international conferences. All results presented will be of group data only, and individual participants will not be identifiable. Parents of participants in the study will be provided with information about the study findings through regular newsletters that include summaries of any published findings.

Discussion

This protocol outlines a prospective cohort study that will examine whether a smartphone app, Baby Moves, used to record infant's GMs for remote GMA, is useful for the early identification of neurodevelopmental impairment in infants born EP/ELBW. GMA is the gold-standard neurodevelopmental assessment for predicting neurodevelopmental outcomes in high-risk infants, and the study will provide important information for clinicians and researchers about the value and practicality of using a smartphone app for GMA in infants born EP/ELBW.

The Baby Moves app provides a format for accessing a GMA that is not limited by geographical distance or clinicians' skill levels at a local service, as users will be able to upload the infant's GMs directly to a GMA trained assessor. Further, since infants can be assessed remotely, it is also likely to be highly cost-effective due to reducing the need to attend clinics on-site for a GMA. However, using the Baby Moves app will not replace infants' current routine medical and neurological follow-up; rather, it offers the ability for additional GMA for those infants who would not have otherwise had access. The Baby Moves app also provides support for the secure downloading of data to mitigate privacy concerns with transferring video data, and as such will be a useful tool for researchers and clinicians. Future development of the app could potentially involve a clinician version, to be used for infants attending follow-up clinics, using similar principles such as prompts for correct technique and secure downloading of data to a purpose built server.

Currently, the Baby Moves app allows parents/caregivers to record their infant's GMs at specific time points between 3 and 4 months of age, in order to capture fidgety GMs which have high predictive validity for neurodevelopmental outcome. Future development of the app is planned so that GMs can be recorded at other time points. Given the potential for the Baby Moves app to be used for remote assessment, future applications of Baby Moves may also include other developmental assessments that can be scored from a video recording by health professionals with expertise in infant development.

While this will be the first study to assess the use of an app to predict CP and other neurodevelopmental outcomes in a geographical cohort, there are limitations to the study. Diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental impairment, such as CP, is a complex process and while we expect that the app will facilitate identification of infants at high risk of CP and/or other neurodevelopmental impairments, it cannot be used alone as a diagnostic tool. Further, smartphone usage in Victoria, Australia may not reflect national and international smartphone usage, and future studies involving other developed countries along with developing countries will be needed.

Acknowledgments

The Baby Moves app was developed in collaboration with Sarva Thurai, Justin Berry and George Charalambous from Curve Tomorrow, a digital health technology company based at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Alicia Spittle at @aliciaspittle

Contributors: AJS, JLYC, JO and LWD were involved in the conception of the smartphone application. All authors were involved in the design of the study and contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Centre for Research Excellence in Newborn Medicine 1060733; Career Development Fellowship 110871 for AJS; Early Career Fellowship 1053787 for JLYC); the Cerebral Palsy Alliance Research Foundation (Project Grant), Murdoch Childrens Research Institute and the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Programme.

Competing interests: AJS and CE are members of the General Movements Trust, a not-for-profit organisation involved in the training of the General Movements Assessment.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Human Research and Ethics Committees at the Royal Children's Hospital, The Royal Women's Hospital, Monash Health and Mercy Health in Melbourne, Australia.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.McIntyre S, Morgan C, Walker K et al. . Cerebral palsy-Don't delay. Dev Disabil Res Rev 2011;17:114–29. 10.1002/ddrr.1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australia Cerebral Palsy Register. http://www.cpregister.com/pubs/pdf/ACPR-Report_Web_2013.pdf, 2013.

- 3.Himpens E, Van den Broeck C, Oostra A et al. . Prevalence, type, distribution, and severity of cerebral palsy in relation to gestational age: a meta-analytic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2008;50:334–40. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02047.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hutchinson EA, De Luca CR, Doyle LW et al. . School-age outcomes of extremely preterm or extremely low birth weight children. Pediatrics 2013;131:e1053–e61. 10.1542/peds.2012-2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spittle AJ, Orton J. Cerebral palsy and developmental coordination disorder in children born preterm. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2014;19:84–9. 10.1016/j.siny.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spittle A, Orton J, Anderson P et al. . Early developmental intervention programmes post-hospital discharge to prevent motor and cognitive impairments in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD005495 10.1002/14651858.CD005495.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heckman JJ. Invest in the very young. Chicago: Ounce of Prevention Fund & University of Chicago, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts G, Howard K, Spittle AJ et al. . Rates of early intervention services in very preterm children with developmental disabilities at age 2 years. J Paediatr Child Health 2008;44:276–80. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01251.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spittle AJ, Boyd RN, Inder TE et al. . Predicting motor development in very preterm infants at 12 months’ corrected age: the role of qualitative magnetic resonance imaging and general movements assessments. Pediatrics 2009;123:512–17. 10.1542/peds.2008-0590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spittle AJ, Spencer-Smith MM, Cheong JL et al. . General movements in very preterm children and neurodevelopment at 2 and 4 years. Pediatrics 2013;132:e452–8. 10.1542/peds.2013-0177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosanquet M, Copeland L, Ware R et al. . A systematic review of tests to predict cerebral palsy in young children. Dev Med Child Neurol 2013;55:418–26. 10.1111/dmcn.12140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Einspieler C, Prechtl HFR. Prechtl's assessment of general movements: a diagnostic tool for the functional assessment of the young nervous system. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 2005;11:61–7. 10.1002/mrdd.20051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Einspieler C, Prechtl HF, Bos AF et al. . Prechtl's method on the qualitative assessment of general movements in preterm, term and young infants. London: MacKeith Press, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spittle AJ, Doyle LW, Boyd RN. A systematic review of the clinimetric properties of neuromotor assessments for preterm infants during the first year of life. Dev Med Child Neurol 2008;50:254–66. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burger M, Louw QA. The predictive validity of general movements-a systematic review. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2009;13:408–20. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulos MN, Wheeler S, Tavares C et al. . How smartphones are changing the face of mobile and participatory healthcare: an overview, with example from eCAALYX. Biomed Eng Online 2011;10:24 10.1186/1475-925X-10-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan WA. Can the ubiquitous power of mobile phones be used to improve health outcomes in developing countries? Global Health 2006;2:9 10.1186/1744-8603-2-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Free C, Phillips G, Watson L et al. . The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001363 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doyle LW, Roberts G, Anderson PJ, Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group. Changing long-term outcomes for infants 500–999g birthweight in Victoria, 1979–2005. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2011;96:F443–47. 10.1136/adc.2010.200576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Einspieler C, Bos AF, Libertus ME et al. . The general movement assessment helps us to identify preterm infants at risk for cognitive dysfunction. Front Psychol 2016;7:406 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hubermann L, Boychuck Z, Shevell M et al. . Age at referral of children for initial diagnosis of cerebral palsy and rehabilitation: current practices. J Child Neurol 2016;31: 364–9. 10.1177/0883073815596610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S et al. . Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997;39: 214–23. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayley N. Bayley scales of infant and toddler development-Third edition. New York: Psychological Corporation, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013446supp1.pdf (64.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013446supp2.pdf (66.2KB, pdf)