Abstract

Background

Breastfeeding in the first hour after birth is important for the success of breastfeeding and in reducing neonatal mortality. Government policies are being developed in this direction, highlighting the accreditation of hospitals in the Baby-Friendly Hospital (BFH) initiative. The aim of this study was to analyze the association between delivery in a BFH (main exposure), compared to non BFH, and timely initiation of breastfeeding (outcome).

Methods

Data came from the “Birth in Brazil” survey, a nationwide hospital-based study of postpartum women and their newborns, coordinated by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation. A sample of 22,035 mothers/babies was analyzed through a hierarchical theoretical model on three levels, and all analyzes considered the complex sample design. Odds ratios were obtained by logistic regression, with a 99 % CI.

Results

Among all births, 40 % occurred in hospitals accredited or in accreditation process for the BFHI and 52 % of women underwent caesarean section. In the final model, at the distal level, mothers less than 35 years old, and those who lived in the North Region, had a higher chance of timely initiation of breastfeeding. At the intermediate level, prenatal care in the public sector and advice on breastfeeding during pregnancy were directly associated with the outcome. At the proximal level, being born in a Baby-Friendly Hospital and vaginal delivery increased the chance of timely initiation of breastfeeding, while prematurity and low birth weight reduced the chance of the outcome.

Conclusions

The chance of being breastfed in the first hour after birth in Baby-Friendly hospitals was twice as high as at non-accredited hospitals, which shows the importance of this initiative for timely initiation of breastfeeding.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0234-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Maternity Hospitals, Maternal-Child Health Services, Cross-Sectional Studies, Postpartum Period, Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

Resumo

Introdução

A amamentação na primeira hora de vida é importante para o sucesso do aleitamento materno e para a redução da mortalidade neonatal. Políticas governamentais vêm atuando neste sentido, destacando-se o credenciamento dos hospitais na Iniciativa Hospital Amigo da Criança (IHAC). O objetivo deste estudo é conhecer a associação entre o nascimento em Hospitais Amigos da Criança (HAC - exposição principal) e o início oportuno da amamentação (desfecho), comparado com maternidades não HAC.

Métodos

Os dados vem do inquérito “Nascer no Brasil”, uma amostra de base hospitalar e abrangência nacional, sob a coordenação da Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. Foram estudados uma amostra de 22.035 mães/bebês através de um modelo teórico hierarquizado em três níveis e todas as análises consideraram o desenho complexo da amostra. As razões de chance foram obtidas por regressão logística, com IC 99 %.

Resultados

Entre o total de nascimentos, 40 % ocorreram em hospitais credenciados ou em processo de credenciamento pela IHAC e 52 % das mulheres foram submetidas à cesariana. No modelo final, no nível distal, as mães com menos de 35 anos, e as que residiam na Região Norte, apresentaram uma chance maior de início oportuno da amamentação. No nível intermediário, a realização de pré-natal no setor público e a orientação sobre amamentação tiveram associação direta com o desfecho. No nível proximal, ter nascido em Hospital Amigo da Criança e via de parto normal aumentaram a chance do início oportuno da amamentação, enquanto ser bebê prematuro e apresentar baixo peso ao nascer reduziram a chance do desfecho.

Conclusões

A chance de uma criança ser amamentada na primeira hora de vida nos hospitais amigos da criança foi duas vezes maior do que nos hospitais não credenciados, o que mostra a importância dessa iniciativa para o início oportuno da amamentação.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0234-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Palavras-chave: Aleitamento materno, Maternidade, Serviços de saúde materno-infantil, Estudos seccionais, Período pós-parto, Iniciativa Hospital Amigo da Criança

Background

The World Health Organization recommends breastfeeding in the first hour after birth as part of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) strategy in order to reduce neonatal mortality [1, 2] and to improve breastfeeding duration [3, 4]. The contact with human milk produced in the first days of life (colostrum), promotes intestinal colonization with saprophytes [5] and enhances the newborn immune system by providing oligosaccharides, immunoglobulin-A and other immune compounds [6]. Brazilian’s Ministry of Health has adopted BFHI as part of its breastfeeding promotion, protection and support policy, having 335 hospitals accredited in this policy in 2010 (http://www.unicef.org/brazil/pt/br_listaIHAC2010.pdf).

Despite the importance of timely initiation of breastfeeding, several barriers to this practice have been identified [7, 8] including mother and hospital related barriers. Among them, caesarean section and hospital practices have major importance, since mothers have little or no power to decide if they are going to breastfeed or not their newborns [8].

Since the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative may play a key role in promoting timely initiation of breastfeeding, this study aimed to identify the association between delivery at a Baby-Friendly Hospital and breastfeeding at the first hour of life.

Methods

This was a hospital-based cross sectional study, with a complex sample to represent all births that occurred in hospitals with more than 500 deliveries/year in Brazil (which correspond to 78.6 % of all hospital births), with field work conducted from February 2011 to October 2012. This study, named “Birth in Brazil: national survey into labor and birth”, was coordinated by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation and the sample was based on the National Information System [9].

The sample design was selected in three stages: in the first stage, hospitals were stratified according to the five Brazilian Regions (North, Northeast, Southeast, Midwest and South), location (state capital and other cities), and type of hospital funding (public, mixed or private), with a total of 30 strata. In this stage 266 hospitals were selected with probability of selection proportional to the number of deliveries in each strata. In the second stage, the number of days needed to interview 90 puerperal women in each hospital was selected by inverse sampling method. In the third stage, the women eligible on each day of the fieldwork were selected. Sample losses due to refusal to participate or hospital discharge were replaced by selecting other puerperal women at the same hospital.

The inclusion criteria to the “Birth in Brazil” survey was: hospital live births with gestational age of more than 22 weeks recorded in the medical file or weight greater than 500 g. All miscarriages were excluded. The sample size was based on a caesarean delivery rate of 46.6 %, to detect differences of 14 % between hospitals, with an alpha of 5 % and power of 95 %, having a minimum of 341 puerperal mothers in each strata.

In total, interviews were conducted with 23,940 women, among 266 hospitals distributed in 191 municipalities, covering all the 27 Brazilian states. Trained field researchers interviewed mothers with an electronic questionnaire in the first 24 h post partum. The questions were related to individual and gestational characteristics, prenatal and delivery care, neonatal characteristics, and breastfeeding at birth. A different questionnaire was applied to the hospital manager. More details about the sample design and field work can be obtained [10].

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of ENSP/FIOCRUZ, under the report n°. 92/2010. Every care was taken towards ensuring privacy and confidentiality of the information. Before each interview was conducted, the interviewee’s consent was obtained, after reading the free and informed consent statement.

The present study investigated the factors associated with breastfeeding at first hour of life (outcome), also denominated ‘timely breastfeeding initiation’, which has been categorized in a dichotomous way (yes, no) based on questions regarding breastfeeding at delivery room and time to initiate breastfeeding. Based on potential conditions that may impede or obstruct breastfeeding at first hour, we have established the following exclusion criteria: mothers tested positive for HIV (according to medical records) and/or with near missing condition [11]; babies who died in the neonatal period; with APGAR < 7 at 5th minute of life; with birth weight <1500 g; and/or gestational age < 32 weeks. In addition, 924 (around 4 %) mothers did not know/answer the questions about breastfeeding initiation, resulting in a final sample of 22,035 mothers and their respective babies.

The exposure variable of being born in a Baby Friendly Initiative Hospital (divided in three categories: yes, in process, and no) was obtained from an interview with the hospital manager and attributed to each mother that had a delivery in that hospital.

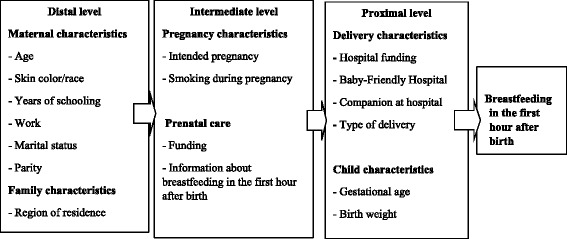

Based on a recent literature review [7] and in a conceptual framework [12], we arranged the confounding variables in a hierarchic model, in three distinct levels based on their proximity to the outcome: distal – mother and family socioeconomic characteristics; intermediate – pregnancy and prenatal characteristics; and proximal – related to delivery conditions and newborn characteristics (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Hierarchical theoretical model to analyze breastfeeding in the first hour after birth

It is important to state that in Brazil we classify race/ethnicity not based on ancestry taxonomy, but based on self-reported skin color/race, according to the official Brazilian Statistic Institute ‘Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística’ definitions, 2010.

All analysis has considered the complex sample design, having the mothers that breastfed their children on the first hour of life as reference, implying to interpret the results as the chance to breastfed in the first hour after birth. Initially we estimated the Chi-square test for each variable and the outcome and obtained the unadjusted Odds Ratio (OR) and the 99 % Confidence Interval (99 % CI). To avoid residual confounding, we selected all variables with p-value ≤ 0.20 to compose the modeling process.

In sequence, we estimated logistic regression models, with 99 % CI, following the hierarchic model (Fig. 1) in three steps: first, adjusting all the distal variables together and removing the ones without statistical significance; second, adjusting the intermediate variables along with the remaining distal variables and removing the intermediate ones that did not achieved p < 0.01; third, adjusting all the proximal variables with the remaining ones from the previous steps – only the variables with p-value <0.01 were retained.

Results

We found that among children born in hospitals with more than 500 deliveries/year in Brazil, 56 % were breastfed in the first hour after birth, when considering only mothers who were able to breastfeed and newborns with suckling conditions. In this study, around one mother in four did not finish the elementary schooling, more than half were primiparous, and almost all received prenatal care. When examining the delivery characteristics, 40 % had their babies in Baby- Friendly Hospitals or in accreditation process, 52 % were submitted to caesarean section delivery, and 8.7 % had premature babies with gestational week varying from 32 0/7 and 36 6/7 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of maternal, hospital and child characteristics, Brazil, 2011

| Variable/categories | Numbera | Percentb | 99 % CIb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | |||

| 12–19 years | 4170 | 18.8 | 17.7–20.1 |

| 20–34 years | 15454 | 70.9 | 69.7–72.1 |

| 35 years or more | 2232 | 10.2 | 9.4–11.1 |

| Missing | 5 | ||

| Skin color/Racec | |||

| White | 7486 | 34.3 | 31.9–36.9 |

| Black | 1835 | 8.4 | 7.3–9.7 |

| Brown | 12150 | 55.7 | 53.3–58.2 |

| Yellow | 233 | 1.1 | 0.8–1.5 |

| Indigenous | 91 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.7 |

| Missing | 4 | ||

| Maternal years of schoolingd | |||

| < = 7 | 5572 | 25.7 | 23.8–27.7 |

| 8 to 10 | 5566 | 25.7 | 24.4–27.0 |

| 11 to 14 | 88556 | 39.4 | 37.1–41.8 |

| 15 or more | 2001 | 9.2 | 7.8–10.9 |

| Missing | 103 | ||

| Maternal work | |||

| No | 12885 | 59.1 | 57.4–60.8 |

| Yes | 8913 | 40.9 | 39.2–42.6 |

| Missing | 1 | ||

| Marital status at delivery | |||

| Without companion/spouse | 3984 | 18.3 | 17.2–19.4 |

| With companion/spouse | 17808 | 81.7 | 80.6–82.8 |

| Missing | 6 | ||

| Parity | |||

| Primiparous | 11618 | 53.3 | 52.0–54.6 |

| Multiparous | 10180 | 46.7 | 45.4–48.0 |

| Missing | 1 | ||

| Brazilian region of residence | |||

| North | 2106 | 9.7 | 8.6–10.9 |

| Northeast | 6160 | 28.3 | 26.0–30.6 |

| Southeast | 9318 | 42.7 | 39.7–45.8 |

| South | 2775 | 12.7 | 11.5–14.0 |

| Middle West | 1440 | 6.6 | 5.5–7.9 |

| Missing | 0 | ||

| Intended pregnancy | |||

| Yes | 9619 | 44.4 | 43.0–45.8 |

| Did not intend to get pregnant now | 5619 | 25.9 | 24.7–27.2 |

| Not at all | 6420 | 29.6 | 28.2–31.1 |

| Missing | 140 | ||

| Funding of prenatal care | |||

| No prenatal care | 233 | 1.1 | 0,8–1.4 |

| Public | 15065 | 69.3 | 67.1–71.4 |

| Mixed | 825 | 3.8 | 3.3–4.4 |

| Private | 5626 | 25.9 | 24.0–27-9 |

| Missing | 49 | ||

| Information about breastfeeding at prenatal care | |||

| No prenatal care | 233 | 1.1 | 0.8–1.4 |

| Yes | 13848 | 35.0 | 33.1–36.9 |

| No | 7624 | 63.5 | 61.6–65.4 |

| Missing | 93 | ||

| Smoking during pregnancy | |||

| No | 19712 | 90.5 | 89.6–91.3 |

| Yes, part of pregnancy | 607 | 2.8 | 2.4–3.3 |

| Yes, whole pregnancy | 1467 | 6.7 | 6.1–7.4 |

| Missing | 13 | ||

| Hospital funding | |||

| Public | 17272 | 79.2 | 77.2–81.1 |

| Private | 4527 | 20.8 | 18.9–22.8 |

| Missing | 0 | ||

| Baby-Friendly Hospitale | |||

| Yes | 7159 | 32.8 | 25.7–40.9 |

| In process | 1571 | 7.2 | 3.7–13.5 |

| No | 13068 | 60.0 | 51.9–67.5 |

| Missing | 0 | ||

| Companion at hospital | |||

| None | 5201 | 23.9 | 20.0–28.2 |

| Part time companion | 12171 | 55.9 | 51.3–60.3 |

| Full time companion | 4418 | 20.3 | 16.5–24.6 |

| Missing | 8 | ||

| Type of delivery | |||

| Normal | 10249 | 47.0 | 44.0–50.0 |

| Forceps | 312 | 1.4 | 0.9–2.3 |

| Intrapartum caesarean | 1766 | 8.1 | 6.9–9.4 |

| Antepartum caesarean | 9472 | 43.5 | 40.9–46.1 |

| Missing | 0 | ||

| Gestational age | |||

| 32 0/7 to 36 6/7 weeks | 1905 | 8.7 | 7.7–10.0 |

| 37 0/7 or more | 19894 | 91.3 | 90.0–92.3 |

| Missing | 0 | ||

| Birth weight | |||

| 2500 g or more | 20181 | 93.4 | 92.5–94.2 |

| 1500–2499 g | 1422 | 6.6 | 5.8–7.5 |

| Missing | 195 | ||

aFinal valid sample of selected mother-child that answered the ‘Birth in Brazil’ questionnaire in 2011, unweighted cases

bFinal valid sample prevalence and 99 % Confidence Interval (99 % CI), considering the complex sample design

cSelf-reported skin color/race, according to Brazilian classification based on ‘Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística’definitions, 2010

dBased on ‘Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística’definitions, 2010

eBased on hospital manager information

In the bivariate analysis, we found an association (p < 0.20) between timely initiation of breastfeeding and the following distal variables: maternal age, skin color/race, maternal years of schooling, maternal work, marital status at delivery, parity, and Brazilian region of residence. Considering the intermediate variables, we found an association with prenatal care funding and information about breastfeeding at prenatal care. The proximal variables associated with the outcome were hospital funding, Baby-Friendly Hospital, type of delivery, gestational age and birth weight (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted factors associated with breastfeeding in the first hour after birth, according to mother, newborn and hospital characteristics, Brazil, 2011

| Variable/categories | Prevalencea | Prevalence 99 % CIa | Unadjusted ORb | Unadjusted OR 99 % CIb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | ||||

| 12–19 years | 62.5 | 58.2–66.6 | 2.01 | 1.60–2.52 |

| 20–34 years | 55.8 | 51.8–59.8 | 1.52 | 1.29–1.81 |

| 35 years or more | 45.3 | 40.1–50.7 | 1.00 | - |

| Skin color/racec | ||||

| White | 51.4 | 46.6–56.2 | 1.00 | - |

| Black | 59.4 | 53.6–64.9 | 1.38 | 1.07–1.79 |

| Brown | 58.1 | 54.0–62.1 | 1.31 | 1.11–1.55 |

| Yellow | 62.6 | 48.7–74.7 | 1.58 | 0.90–2.78 |

| Indigenous | 75.7 | 53.4–89.8 | 2.94 | 1.03–8.41 |

| Maternal years of schoolingd | ||||

| < = 7 | 62.8 | 58.7–66.7 | 2.72 | 2.08–3.55 |

| 8 to 10 | 61.4 | 57.1–65.7 | 2.57 | 1.96–3.36 |

| 11 to 14 | 52.2 | 47.6–56.9 | 1.76 | 1.41–2.19 |

| 15 or more | 38.3 | 32.6–44.3 | 1.00 | - |

| Maternal work | ||||

| No | 60.0 | 56.2–63.8 | 1.49 | 1.31–1.70 |

| Yes | 50.2 | 45.8–54.6 | 1.00 | - |

| Marital status at delivery | ||||

| Without companion/spouse | 59.0 | 54.3–63.4 | 1.16 | 1.02–1.31 |

| With companion/spouse | 55.4 | 51.5–59.1 | 1.00 | - |

| Parity | ||||

| Primiparous | 58.6 | 54.7–62.4 | 1.00 | - |

| Multiparous | 53.1 | 48.9–57.3 | 1.25 | 1.11–1.50 |

| Brazilian region of residence | ||||

| North | 71.0 | 65.3–76.1 | 2.30 | 1.56–3.39 |

| Northeast | 53.7 | 47.6–59.7 | 1.09 | 0.75–1.59 |

| Southeast | 51.5 | 44.4–58.6 | 1.00 | - |

| South | 61.1 | 50.7–70.6 | 1.48 | 0.89–2.47 |

| Middle West | 63.1 | 55.7–70.0 | 1.61 | 1.06–2.46 |

| Intended pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 54.0 | 49.9–58.1 | 1.00 | - |

| Did not intend to get pregnant now | 56.7 | 52.2–61.1 | 1.17 | 0.98–1.26 |

| Not at all | 58.6 | 54.2–62.7 | 1.20 | 1.04–1.40 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | ||||

| No | 55.6 | 51.8–59.3 | 1.00 | - |

| Yes, part of pregnancy | 57.3 | 49.0–65.3 | 1.07 | 0.81–1.43 |

| Yes, whole pregnancy | 61.0 | 54.7–66.9 | 1.25 | 1.01–1.55 |

| Funding of prenatal care | ||||

| No prenatal care | 52.8 | 40.2–65.0 | 1.71 | 0.98–2.99 |

| Public | 62.4 | 58.3–66.3 | 2.55 | 1.97–3.29 |

| Mixed | 52.7 | 45.3–60.0 | 1.71 | 1.23–2.38 |

| Private | 39.5 | 33.7–45.6 | 1.00 | - |

| Information about breastfeeding at prenatal care | ||||

| No prenatal care | 52.8 | 40.2–65.0 | 1.02 | 0.61–1.71- |

| Received | 58.2 | 54.5–61.8 | 1.28 | 1.11–1.48 |

| Did not receive | 52.2 | 47.2–57.0 | 1.00 | - |

| Hospital fundinge | ||||

| Public | 61.1 | 57.0–65.1 | 2.73 | 1.94–3.86 |

| Private | 36.5 | 29.4–44.3 | 1.00 | - |

| Baby-Friendly Hospitale | ||||

| Yes | 69.4 | 64.9–73.6 | 2.49 | 1.85–3.34 |

| In process | 63.9 | 51.0–75.1 | 1.94 | 1.11–3.41 |

| No | 47.7 | 42.5–53.0 | 1.00 | - |

| Companion at hospital | ||||

| None | 55.6 | 49.8–61.2 | 1.00 | - |

| Part time companion | 54.3 | 49.8–58.8 | 0.95 | 0.75–1.20 |

| Full time companion | 61.1 | 55.4–66.6 | 1.26 | 0.92–1.72 |

| Type of delivery | ||||

| Normal | 70.3 | 66.2–74.1 | 3.29 | 2.67–4.06 |

| Forceps | 60.3 | 47.9–71.5 | 2.11 | 1.27–3.51 |

| Intrapartum caesarean | 48.7 | 43.0–54.4 | 1.32 | 1.07–1.63 |

| Antepartum caesarean | 41.8 | 37.2–46.5 | 1.00 | - |

| Gestational age | ||||

| 32 0/7 to 36 6/7 weeks | 37.4 | 32.9–42.1 | 0.44 | 0.36–0.53 |

| 37 0/7 or more | 57.8 | 53.9–61.6 | 1.00 | - |

| Birth weight | ||||

| 1500–2499 g | 57.4 | 53.5–61.2 | 0.42 | 0.36–0.50 |

| 2500 g or more | 36.3 | 31.0–42.0 | 1.00 | - |

| Total | 56.0 | 52.2–59.7 | ||

aFinal valid sample prevalence and 99 % Confidence Interval (99 % CI), considering the complex sample design

bUnadjusted Odds Ratio (OR) and 99 % CI, considering the complex sample design

cSelf-reported skin color/race, according to Brazilian classification based on ‘Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística’definitions, 2010

dBased on ‘Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística’definitions, 2010

eBased on hospital manager information

In the final adjusted model, mothers with higher likelihood to breastfeed in the first hour after birth were less than 35 years old, residents at the North Region of Brazil (compared to the Southeast region), with prenatal care at the public sector, and who received information about breastfeeding at the first hour of life in this period. The mothers that gave birth at a Baby-Friendly Hospital and with vaginal delivery also had a higher odds to timely initiation of breastfeeding. Low birth weight and premature babies had lower odds of being breastfed in the first hour after birth (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with breastfeeding in the first hour after birth in the final adjusted model, Brazil, 2011

| Variable/categories | AORa | 99 % Confidence Intervala |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | ||

| 12–19 years | 1.33 | (1.02–1.74) |

| 20–34 years | 1.23 | (1.01–1.50) |

| 35 years or + | 1.00 | - |

| Brazilian region of residence | ||

| North | 1.81 | (1.19–2.76) |

| Northeast | 0.92 | (0.63–1.35) |

| Middle West | 1.43 | (0.83–2.46) |

| South | 1.37 | (0.81–2.32) |

| Southeast | 1.00 | - |

| Funding of prenatal care | ||

| No prenatal care | 0.96 | (0.20–4.74) |

| Public | 1.33 | (1.01–1.76) |

| Mixed | 1.35 | (0.92–1.99) |

| Private | 1.00 | - |

| Information about breastfeeding at prenatal care | ||

| No prenatal care | 1.03 | (0.30–3.56) |

| Yes | 1.38 | (1.17–1.63) |

| No | 1.00 | - |

| Baby-Friendly Hospitalb | ||

| Yes | 2.07 | (1.50–2.86) |

| In process | 1.44 | (0.71–2.93) |

| No | 1.00 | - |

| Type of delivery | ||

| Normal | 2.81 | (2.19–3.62) |

| Forceps | 2.11 | (1.30–3.44) |

| Intrapartum caesarean | 1.18 | (0.94–1.48) |

| Antepartum caesarean | 1.00 | - |

| Gestational age | ||

| 32 0/7 to 36 6/7 weeks | 0.47 | (0.38–0.59) |

| 37 0/7 or more | 1.00 | - |

| Birth weight | ||

| 1500–2499 g | 0.51 | (0.39–0.66) |

| 2500 g or more | 1.00 | - |

aAdjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) and 99 % CI, obtained from a logistic regression model and considering the complex sample design, adjusted for educational level and parity

bBased on hospital manager information

Discussion

More than half (56 %) of the babies born in Brazil in 2011–12, with conditions that allowed breastfeeding, were timely breastfed, which represents an improvement compared to the 43 % timely breastfed babies observed in the National Survey of Demography and Health conducted in 2006 (PNDS, 2006). However, the results obtained were below those found in a survey held in 2008 in the Brazilian capitals, where 67 % of the babies were breastfed in the first hour after birth [13]. This disparity may be due to methodological differences and to the sample strategy, as the 2008 survey was conducted only in capitals and with children under one year old, while the current “Birth in Brazil” survey had a broader sample and interviewed mothers in the first day after birth, decreasing the possibility of recall bias.

Several breastfeeding indicators have improved in Brazil since the National Breastfeeding Program was released by the Ministry of Health in 1981 [14]. However, only the indicator “breastfeeding in the first hour after birth” achieved the WHO status of “good” (between 50–89 % - MS, 2009). The WHO recommends putting the babies in skin-to-skin contact soon after delivery, giving mothers support to start breastfeeding within this sensitive period [15], since the newborn has the reflex to search by himself the mother’s areola [16].

Among all Brazilian deliveries, four in ten occurred in Baby-Friendly Hospitals (33 %) or in those in process to become BFH (7 %), which represents a great improvement compared to 2004, when only one in four deliveries occurred in BFH [17]. In Brazil, in 2011, the chance of being breastfed in the first hour after birth doubled if the child was born in a BFH.

A similar effect was observed in a maternity hospital in the accreditation process to become BFH in the South of Brazil [18], corroborating the importance of BFH accreditation to improve not only timely breastfeeding, but also exclusive breastfeeding duration among healthy newborns [19] and those that need intensive care treatment [20], as well as to reduce pacifier use [21].

Although WHO recommends a caesarean section delivery rate of 10 % [22], our study found a c-section rate of 52 %. These rates differed between BFH (40.6 %) and non BFH (58.9 %), which may be explained by an additional criteria established by the Brazilian Ministry of Health for certification as a Baby-Friendly Hospital (besides the UNICEF/WHO requirements of compliance with the 10 steps): the reduction of caesarean section rates [23]. In the “Birth in Brazil” study, children born by vaginal delivery had almost a three times chance of being breastfed in the first hour after birth than those born by c-section. This is consistent with the results of a study conducted in Rio de Janeiro, where c-section reduced by half the prevalence of breastfeeding in the first hour after birth [8], and with the findings of a systematic review: c-section is the most frequent factor negatively associated with timely breastfeeding [7], since post partum procedures and routines may delay the early contact between mother and baby.

Moreira et al. [24] reported a synergic effect of vaginal delivery and Baby-Friendly Hospitals, as both represent good hospital practices to the newborn. We assume that caesarean section should not represent a risk to timely breastfeeding if both newborns and mothers are in good condition if the surgery occurs after initiation of labor signs, which could indicate the newborn maturity to initiate breastfeeding. However, the caesarean rate in Brazil is significantly higher in the private sector, with approximately 80 % of caesarean sections carried out without the mother having gone into labor [25].

Both premature and low birth weight newborns had half the chance of being breastfed in the first hour after birth. This can be due to unnecessary routines and interventions (oxygen therapy, aspirating the superior airways, among others) that may unnecessarily separate mother and child in the delivery room [24]. Our study only included premature newborns with 32 0/7 to 36 6/7 gestational weeks, and low birth weight children between 1500 and 2499 g, conditions which, besides inspiring extra care, may not be a barrier to breastfeeding in the first hour after birth. It is important to improve both prematurity prevention and neonatal care to the most vulnerable children [26], since another study also showed prematurity as a risk factor to breastfeeding in the first hour after birth [27].

Mothers that received information about breastfeeding during prenatal care had higher chances to breastfed their babies in the first hour after birth, similar to the result of a study conducted in Bahia [27] (Vieira, 2010), showing the importance of prenatal care to breastfeeding initiation.

Considering distal factors, only mother’s age and region of residence were associated with the outcome. A study in the South of Brazil also found an association between mother’s age above 34 years and lower chances of breastfeeding in the first hour after birth [18]. This result could be due to a cohort effect, as older mothers were less exposed to the increasing practice of breastfeeding at birth in Brazil [28]. As to the region of residence, a national survey conducted in 2006 [28] and a study in the Brazilian capitals in 2008 [13] evidenced a higher prevalence of breastfeeding in the first hour in the North region of Brazil, what can be due to cultural factors, since most of the indigenous population are concentrated in this region.

Conclusions

The studied proximal factors were the most strongly associated with timely breastfeeding, bringing evidence about the importance of adopting Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative to improve perinatal practices and timely breastfeeding initiation. Special attention should be given to the negative association found between caesarean section delivery without clinical indication and breastfeeding in the first hour after birth, bringing more evidence to the ongoing government efforts to diminish this harmful practice in Brazil. Prematurity and low birth weight are factors difficult to be modified, but gains in prenatal care access and quality could contribute to a decline on their prevalence and to improve timely breastfeeding rates. We recommend the reinforcement of BFHI implementation, extending this initiative to the private sector. This measure could contribute not only to improve timely breastfeeding rates, but also reducing unnecessary caesarean section delivery.

Portuguese version

A Portuguese translation of this article is available as Additional file 1.

Peer review

The reviewer reports for this article are available as Additional file 2.

Acknowledgments

Declarations

This article has been published as part of Reproductive Health Volume 13 Supplement 3, 2016: Childbirth in Brazil. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-13-supplement-3. Publication of the supplement was funded by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation.

Authors’ contributions

MLC, CSB, MICO and MCL participated in the study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript, and are accountable for all the information provided. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Financial support

This research received financial support from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and from the National School of Public Health - FIOCRUZ, Brazil.

Abbreviations

- APGAR

Refers to some organic parameters considered in the first minutes of life: A - Activity; P - Pulse ; G - Grimace (reflex readiness); A - Appearance (skin color); R - Respiration

- BFH

Baby-Friendly Hospital

- BFHI

Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

- CI

Confidence interval

- ENSP

National School of Public Health

- FIOCRUZ

Oswaldo Cruz Foundation

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- OR

Odds ratio

- UNICEF

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund

- WHO

World Health Organization

Additional files

Portuguese version. (DOCX 82 kb)

Peer review. (DOCX 28 kb)

Contributor Information

Márcia Lazaro de Carvalho, Phone: +55 (21) 2598-2623, Email: marcialazaroc@gmail.com.

Maria Inês Couto de Oliveira, Phone: +55(21) 2629-9342, Email: marinesco@superig.com.br.

References

- 1.Edmond KM, Zandoh C, Quigley MA, Amenga-Etego S, Owusu-Agyei S, Kirkwood BR. Delayed breastfeeding initiation increases risk of neonatal mortality. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):e380–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boccolini CS, Carvalho ML, Oliveira MIC, Pérez-Escamilla R. Breastfeeding during the first hour of life and neonatal mortality. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2013;89(2):131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson GC, Moore E, Hepworth J, Bergman N. Early skin to skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Sist Rev. 2007;3:CD003519. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bystrova K, Ivanova V, Edhborg M, Matthiesen AS, Ranjsö-Arvidson AB, Mukhamedrakhimov R, et al. Early contact versus separation: effects on mother–infant interaction one year later. Birth. 2009;36(2):97–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albesharat R, Ehrmann MA, Korakli M, Yazaji S, Vogel RF. Phenotypic and genotypic analyses of lactic acid bacteria in local fermented food, breast milk and faeces of mothers and their babies. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2011;34:148–55. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballard O, Morrow AL. Human Milk Composition: Nutrients and Bioactive Factors. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(1):49–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esteves TMB, Daumas RP, Oliveira MIC, Andrade CAF, Leite IC. Factors associated to breastfeeding in the first hour after birth: systematic review. Rev Saude Publica [online] 2014;48(4):697–708. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2014048005278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boccolini CS, Carvalho ML, Oliveira MIC, Vasconcellos AGG. Factors associated with breastfeeding in the first hour after birth. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45(1):69–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Leal MC, Pereira APE, Domingues RMSM, Theme Filha MM, Dias MAB, Nakamura-Pereira M et al. Obstetric interventions during labor and childbirth in Brazilian low-risk women. Cad. Saude Publica. 2014; 30 suppl.1:S17-32 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Leal MC, Silva AAM, Dias MAB, Gama SGN, Rattner D, Moreira ME, et al. Birth in Brazil: national survey into labour and birth. Reprod Health. 2012;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dias MAB, Domingues RMSM, Schilithz AOC, Nakamura-Pereira M, Diniz CSG, Brum IR, et al. Incidence of maternal near miss in hospital childbirth and postpartum: data from the Birth in Brazil study. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30 Sup:S169–81. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00154213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC, Olinto MT. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(1):224–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministério da Saúde . II Pesquisa de Prevalência de Aleitamento Materno nas Capitais Brasileiras e Distrito Federal. Brasília: Editora do Ministério da Saúde; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rea MF. Reflexões sobre a amamentação no Brasil: de como passamos a 10 meses de duração. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19(Suppl 1):S37–45. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2003000700005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Baby-friendly hospital initiative: revised, updated and expanded for integrated care. Section 2. Strengthening and sustaining the baby-friendly hospital initiative: a course for decision-makers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed]

- 16.Righard L, Alade M. Effect of delivery room routines on success of first breast-feed. Lancet. 1990;336:1105–7. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araújo MF, Schmitz BA. Twelve years of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative in Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2007;2(2):91–9. doi: 10.1590/S1020-49892007000700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silveira RB, Albernaz E, Zuccheto LM. Factors associated with the initiation of breastfeeding in a city in the south of Brazil. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant. 2008;8(1):35–43. doi: 10.1590/S1519-38292008000100005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abrahams SW, Labbok MH. Exploring the impact of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative on trends in exclusive breastfeeding. Int Breastfeed J [online] 2009;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vannuchi MTO, Monteiro CA, Rea MF, Andrade SM, Matsuo T. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative and breastfeeding in a neonatal unit. Rev Saude Publica [online] 2004;38(3):422–8. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102004000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venancio SI, Saldiva SRDM, Escuder MML, Giugliani ERJ. The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative shows positive effects on breastfeeding indicators in Brazil. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:914–8. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye J, Betrán AP, Guerrero Vela M, Souza JP, Zhang J. Searching for the optimal rate of medically necessary caesarean delivery. Birth Berkeley Calif. 2014;41(3):237–44. doi: 10.1111/birt.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortiz PN, Rolim RB, Souza MFL, Soares PL, Vieira TO, Vieira GO, et al. Comparing breast feeding practices in baby friendly and non-accredited hospitals in Salvador, Bahia. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant. 2011;11(4):405–13. doi: 10.1590/S1519-38292011000400007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreira MEL, Gama SGN, Pereira APE, Silva AAM, Lansky S, Pinheiro RS, et al. Clinical practices in the hospital care of healthy newborn infant in Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30 Sup(30 Sup):S128–39. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00145213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domingues RMSM, Dias MABD, Nakamura-Pereira M, Alves JT, d’Orsi E, Pereira APE, et al. Process of decision-making regarding the mode of birth in Brazil: from the initial preference of women to the final mode of birth. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30 Sup:S101–16. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00105113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lansky S, Friche AAL, Silva AAM, Campos D, Bittencourt DAS, Carvalho ML, et al. Birth in Brazil survey: neonatal mortality, pregnancy and childbirth quality of care. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30 Sup:S192–207. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00133213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vieira TO, Vieira GO, Giugliani ERJ, Mendes CMC, Martins CC, Silva LR. Determinants of breastfeeding initiation within the first hour after birth in a Brazilian population: cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:760. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ministério da Saúde . Pesquisa Nacional de Demografia e Saúde da Criança e da Mulher. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2008. [Google Scholar]