Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study is to elicit the amount of safety margin necessary around the ameloblastic lesion in view of preventing further recurrence.

Materials and Methods:

The study consisted of 25 cases of mandibular ameloblastoma. Diagnosis was based on clinical and radiological analysis and confirmed by histopathological report. An incisional biopsy was done preoperatively to confirm the diagnosis. Segmental resection was planned for all the cases. After the resection, postoperative panoramic radiograph of the specimen was taken followed by histopathological examination of its margin to detect tumor cell infiltration.

Results and Conclusion:

In all our cases, the ameloblastoma was infiltrating in nature. A follow-up period of 10 years showed neither recurrence nor implant failure. In our study, we conclude our safe margin for infiltrating variant of ameloblastoma based on histopathological report of the resected specimen.

KEY WORDS: Ameloblastoma, mandible, multicystic, resection, unicystic

Ameloblastoma is a benign epithelial odontogenic tumor that often shows aggressive growth and high recurrence rate following conservative surgical treatment.[1] It is the most controversial tumor of the jaws because a greater diversity of opinion has existed concerning the clinical behavior, treatment, and malignant potential of this tumor than perhaps any other neoplasms found elsewhere in the body. The tumor has been aptly described by Robinson as a tumor that is usually “unicentric, nonfunctional, intermittent in growth, anatomically benign, and clinically persistent.”[2] The growth characteristics of the tumor were classified into two major types: Expansive and invasive. The expansive type was defined as a tumor clearly demarcated from the surrounding fibrous connective tissues, with epithelium being flat or toothed shape. The invasive type was defined as one in which the epithelial islets of the tumor were infiltrated into the surrounding tissue in a cord-like, sporadic, or diffuse pattern, which plays an important role in the rate of recurrence following conservative surgical treatment. Ameloblastoma accounts for approximately 10% of all odontogenic tumors and 1% of the cysts of the jaws.[3] Several treatment modalities have been tried by various authors which include:[4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]

Curettage

Enucleation

Chemical cauterization

Electro cauterization

En bloc excision

Radical resection

Radiotherapy/chemotherapy.

Secondary surgeries to eradicate recurrent tumors tend to be challenging and reconstruction is difficult because of the altered anatomy of the surgical site and tumor infiltration into the adjacent vital structures.[16] Hence, it becomes mandatory to take all the precautions during primary surgery to avoid recurrence by establishing a safe margin around the lesion. A suitable method of assessing this is through examining the periphery of the resected ameloblastoma specimens microscopically.

Materials and Methods

The reference literatures were retrieved from PubMed and ScienceDirect database. The search words used were ameloblastoma, recurrence rate of ameloblastoma, unicystic, multicystic, treatment modalities, and ameloblastoma of mandible. Further articles were retrieved using cross references in these literatures. About 25 cases (12 females and 13 males) with ameloblastoma involving the mandible reported were evaluated for safe margin. The ages of the patients range from 17 years to 58 years with an average of 37.5 years. Male to female ratio is approximately 1:1. Routine blood investigations were taken. All the patients were clinically examined. Panoramic radiograph was taken. Twenty-three of our patients showed multilocular radiolucent pattern and the other two patients had unilocular radiolucent pattern. An incisional biopsy was performed. On histopathological examination, biopsy specimen showed 12 cases as follicular ameloblastoma, 7 cases as plexiform ameloblastoma, 4 cases as acanthomatous ameloblastoma, and 2 cases as unicystic ameloblastoma. Radiographically, a safe margin of 1.5 cm was marked from the radiographic border of the lesion. Under general anesthesia, segmental resection of the mandible with a surgical clearance of 1.5 cm as planned with the preoperative panoramic radiograph was made. Patients were kept under antibiotic cover for 1 week, fed by Ryles tube for 10 days to avoid contamination. They were discharged after 10 days. After the resection, postoperative specimen margin was cut vertically into 2 pieces as 0.75 cm of equal thickness by a fret saw to detect tumor cell infiltration [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Postoperative resected specimen

Figure 2.

Postoperative resected specimen radiograph

Results

From our study of resection and safe margin, we find that the multicystic variant of ameloblastoma is much more aggressive when compared with unicystic variant. In our case, the unicystic variant showed an infiltration rate up to 0.2 cm [Figure 3]. The acanthomatous ameloblastoma showed 0.5 cm infiltration [Figure 4] and follicular [Figure 5] and plexiform variants showed 0.75 cm infiltration from the radiological margin [Figure 6]. A regular monthly follow-up was made for a minimum period of 6 months to a maximum of 12 months followed by review of every 6 months for a period of 10 years. None of them showed clinical or radiological evidence of recurrence, but there is a possibility for the tumor cells to be present even beyond the radiological extent, especially for about 1 cm. Hence, a clearance of 1.5 cm on either side of the lesion during resection is thought to be advisable.

Figure 3.

Postoperative histopathological analysis showed unicystic variant with infiltration up to 0.2 cm

Figure 4.

Postoperative histopathological analysis showed acanthomatous variant with infiltration up to 0.5 cm

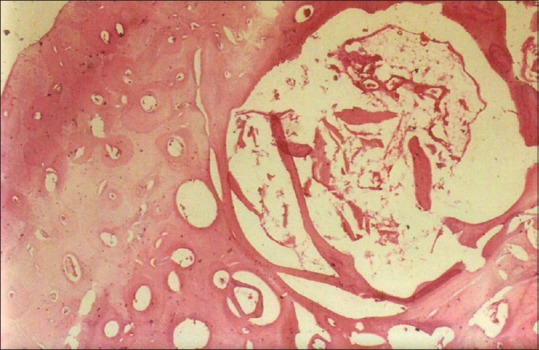

Figure 5.

Postoperative histopathological analysis showed follicular variant with infiltration up to 0.75 cm

Figure 6.

Postoperative histopathological analysis showed plexiform variant with infiltration up to 0.75 cm

Discussion

Ever since the term “Adamantinoma” was coined by Mallassez in 1885, controversy has prevailed as to the most versatile form of treatment to prevent recurrence of the lesion. The origin of ameloblastoma is still controversial, but recently, the dental lamina has been accepted more than the enamel organ, epithelial rests, basal cells of the surface epithelium or epithelium of the odontogenic cysts as stated by Williams in 1993.[17] Until the study by Eversole et al., in 1984, ameloblastomas were classified according to the histological findings into follicular, plexiform, acanthomatous, granular cell, basal cell, squamous metaplastic, and other rare types.[18] In recent years, the literature has divided clinical ameloblastoma into unicystic, multicystic or solid, peripheral, and malignant subtypes.[1] Robinson on reviewing 293 cases reported an incidence of 83.7% in the mandible and 16.3% in the maxilla.[19,20] In addition, Kameyama et al. in 1987 reported that there was a striking predilection for mandible with a mandible: Maxilla ratio of 23:1 in their clinico-pathological analysis containing 72 cases.[21] Riechart et al. in 1995 noted that mandible was affected over five times as frequently as the maxilla.[22] Sehdev et al. in 1974 analyzed 72 patients with ameloblastoma of mandible and they concluded that the conservative approach (curettage) led to 90% recurrence of mandibular ameloblastoma. Shatkin in 1965 and Sehdev in 1974 reported twenty cases of ameloblastoma and observed that 86% of the mandibular lesions recurred after curettage compared to a 14% recurrence rate after en bloc resection.[15,23] Müller and Slootweg in 1985 found a 52% rate of recurrence in patients with primary ameloblastoma treated conservatively and a 25% rate of recurrence in patients with primary tumors treated by the radical approach.[24] Curi et al., 1997, in their study showed that the management of ameloblastoma with liquid nitrogen spray cryosurgery decreases the local recurrence rate.[25] Bradley reported several complications after cryosurgery therapy such as infection, sequestration, and pathologic fracture can appear because of a failure of adequate soft tissue cover.[4] In 1984, Atkinson et al. reported the use of mega voltage radiation for ten patients with recurrent ameloblastoma. Five of the six patients with mandibular tumor had a reduction in tumor size only.[1] There is a danger of postradiation sarcoma as reported by Becker and Pertl in 1967 and of osteoradionecrosis.[26] Small and Waldron in 1955 suggested that cauterization of the cavity after curettage is potentially more effective than curettage alone.[27] Muller and Slootweg (1985) and Curi in 1997 defined radical treatment as a procedure in which the intention was to remove the ameloblastoma with a margin of normal bone and any treatment that differed from this was defined as conservative.[24,25]

Although few authors suggest enucleation and curettage in Type I and Type II unicystic variants of ameloblastoma; in contrast, tumor cell invasion into the adjacent bone cannot be ruled out if there is a proliferation of ameloblastic cells lining the cystic lumen into the periphery of the connective tissue wall or if the island of ameloblastic cells were seen in the wall. The resected specimens of our cases consisted 1.5 cm of radiologically normal-appearing bone on either side of the lesion. The so-called normal bone part of the specimen which is 1.5 cm in thickness is divided into two halves measuring 0.75 cm each. Same division is done on the other side of the specimen also. The 0.75 cm slice of bone that was at the farthest part of the lesion revealed no invasion by the tumor tissue. Whereas the ten patients of follicular and plexiform variants show infiltration of 0.75 cm bone contained in the ameloblastoma cells. Hence, it is considered that 1 cm of clearance may not be adequate. In view of the recurrence-free concept of ameloblastoma resections, at least 1.5 cm of surgical clearance is essential.

Conclusion

From our study, we conclude that resection is the choice of treatment for infiltrating type of ameloblastoma. A preoperative biopsy is mandatory to find out the type of ameloblastoma. Based on the histological type of ameloblastoma, we suggest that radical resection with a safe margin of 1.5 cm followed by the reconstruction of the defect gives a good functional and esthetic outcome.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Atkinson CH, Harwood AR, Cummings BJ. Ameloblastoma of the jaw.A reappraisal of the role of megavoltage irradiation. Cancer. 1984;53:869–73. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840215)53:4<869::aid-cncr2820530409>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackermann GL, Altini M, Shear M. The unicystic ameloblastoma: A clinicopathological study of 57 cases. J Oral Pathol. 1988;17:541–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1988.tb01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aisenberg MS. Histopathology of ameloblastomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1953;6:1111–28. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(53)90223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley PF. Modern trends in cryosurgery of bone in the maxillo-facial region. Int J Oral Surg. 1978;7:405–15. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(78)80116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner DG. Peripheral ameloblastoma: A study of 21 cases, including 5 reported as basal cell carcinoma of the gingiva. Cancer. 1977;39:1625–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197704)39:4<1625::aid-cncr2820390437>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emmings FG, Gage AA, Koepf SW. Combined curettage and cryotherapy for recurrent ameloblastoma of the mandible: Report of case. J Oral Surg. 1971;29:41–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher AD, Williams DF, Bradley PF. The effect of cryosurgery on the strength of bone. Br J Oral Surg. 1978;15:215–22. doi: 10.1016/0007-117x(78)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furuki Y, Fujita M, Mitsugi M, Tanimoto K, Yoshiga K, Wada T. A radiographic study of recurrent unicystic ameloblastoma following marsupialization.Report of three cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1997;26:214–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller H, Slootweg PJ. The ameloblastoma, the controversial approach to therapy. J Maxillofac Surg. 1985;13:79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(85)80021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macintosh RB. Aggressive surgical management of ameloblastoma. Clin Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;3:73. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyamoto CT, Brady LW, Markoe A, Salinger D. Ameloblastoma of the jaw.Treatment with radiation therapy and a case report. Am J Clin Oncol. 1991;14:225–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura N, Higuchi Y, Tashiro H, Ohishi M. Marsupialization of cystic ameloblastoma: A clinical and histopathologic study of the growth characteristics before and after marsupialization. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:748–54. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olaitan AA, Arole G, Adekeye EO. Recurrent ameloblastoma of the jaws. A follow-up study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;27:456–60. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(98)80037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sachs SA. Surgical excision with peripheral ostectomy a definitive, yet conservative, approach to the surgical management of ameloblastoma. Oral maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1991;3:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shatkin S, Hoffmeister FS. Ameloblastoma: A rational approach to therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:421–35. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(65)90231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Axhausen H, Sonessan G, Leder G. Ameloblastoma originating from odontogenic cysts. J Oral Pathol Med. 1991;20:318. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1991.tb00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams TP. Management of ameloblastoma: A changing perspective. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:1064–70. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80440-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eversole LR, Leider AS, Hansen LS. Ameloblastomas with pronounced desmoplasia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42:735–40. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(84)90423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson L, Martinez MG. Unicystic ameloblastoma: A prognostically distinct entity. Cancer. 1977;40:2278–85. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197711)40:5<2278::aid-cncr2820400539>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson HB. Ameloblastoma: A survey of three hundred and seventy nine cases from the literature. Arch Pathol. 1937;23:831–43. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kameyama Y, Takehana S, Mizohata M, Nonobe K, Hara M, Kawai T, et al. A clinicopathological study of ameloblastomas. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;16:706–12. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(87)80057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP, Sonner S. Ameloblastoma: Biological profile of 3677 cases. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1995;31B:86–99. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(94)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sehdev MK, Huvos AG, Strong EW, Gerold FP, Willis GW. Proceedings: Ameloblastoma of maxilla and mandible. Cancer. 1974;33:324–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197402)33:2<324::aid-cncr2820330205>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Müller H, Slootweg PJ. The growth characteristics of multilocular ameloblastomas. A histological investigation with some inferences with regard to operative procedures. J Maxillofac Surg. 1985;13:224–30. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(85)80052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curi MM, Dib LL, Pinto DS. Management of solid ameloblastoma of the jaws with liquid nitrogen spray cryosurgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:339–44. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker R, Pertl A. On the therapy of ameloblastoma. Dtsch Zahn Mund Kieferheilkd Zentralbl Gesamte. 1967;49:423–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Small IA, Waldron CA. Ameloblastomas of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1955;8:281–97. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(55)90350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]