Abstract

Aim:

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the short-term clinical and microbiological effect of chlorhexidine varnish when used as an adjuvant to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

A split-mouth design was conducted in 11 patients suffering from chronic periodontitis. The control site underwent scaling and root planing, and the experimental site was additionally treated with chlorhexidine varnish application. Clinical parameters, namely, gingival index (GI), plaque index (PI), bleeding on probing (BoP), probing pocket depth (PPD), and clinical attachment level were recorded at baseline, 1 month, and 3 months postoperatively. Furthermore, microbial examination of the plaque samples was done at baseline, 1 month, and 3 months.

Results:

Both treatment strategies showed significant improvement in GI, PI, BoP, PPD, and clinical attachment level, at both follow-up visits by comparison with baseline levels. At study termination, chlorhexidine varnish implemented treatment strategy resulted in additional improvement in the clinical parameters, and more reduction in the total anaerobic count at 1 month and 3 months.

Conclusions:

These findings suggest that a chlorhexidine varnish implemented treatment strategy along with scaling and root planing may improve the clinical outcome for the treatment of chronic periodontitis in comparison to scaling and root planing alone.

KEY WORDS: Chlorhexidine, chronic periodontitis, varnish

Periodontitis is considered to be a multifactorial disease,[1] where the destruction of the periodontium is a result of interactions between a complex subgingival microbial population and specific host defense mechanism.

Conventional treatment of periodontal disease includes mechanical debridement of the tooth surface to disrupt the microflora and provide a clean and biologically compatible root surface. However, mechanical debridement has limited efficiency in deep pockets and in furcation areas. Limited access causes incomplete debridement. Therefore, treatment strategies using antimicrobials in conjugation with mechanical debridement have been evolved.[2,3,4]

Systemic antibiotics have been proved to be effective as an adjuvant to mechanical debridement, but their use should be limited because of the possibility of development of drug resistance. Therefore, treatment strategies using locally delivered antimicrobials in conjunction with scaling and root planing have evolved.[5]

Chlorhexidine digluconate is the most effective and safest antiplaque agent that has been developed to date. Chlorhexidine is still considered as the gold standard in chemically controlling plaque accumulation.

The vehicles most often used to administer chlorhexidine are mouthrinses, aerosols, gels, and varnishes. The varnishes have been developed over the past decade. Varnishes are the most popular of the sustained release delivery systems applied to the teeth. They are most effective for professional application of chlorhexidine, as they are easy to apply, and they stay in place for a longer time.[6]

The present study aims at investigating the short-term clinical effect of chlorhexidine varnish when used as an adjuvant to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods

Eleven patients of both sexes aged between 35 and 60 years and diagnosed as chronic periodontitis were selected for the study.

Patients chosen for the study had pocket depth >5 mm that bled on probing, in each of the quadrants selected for the study.

A split-mouth study design was used so that each patient acted as their own control. One quadrant on each side was randomized to the two treatment arms.

Control site: Scaling and root planing alone

Experimental site: Scaling and root planning and chlorhexidine varnish application.

Patient selection criteria

Inclusion criteria

Patients had at least twenty teeth, with a minimum of four multirooted teeth and four teeth per quadrant

All patients suffered from chronic periodontitis

15% of the pockets were >5 mm that bled upon probing

Radiographic evidence of bone loss was also present.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who have taken antibiotics within 4 months before or during the trial and patients using antiseptics during the trial

Patients suffering from systemic diseases and/or taking medications likely to induce gingival hypertrophy

Patients wearing removable dentures and undergoing orthodontic treatment

Teeth neighboring recent extraction sockets

Teeth showing endodontic–periodontic lesions.

Experimental design

All the patients received standard periodontal therapy, meaning scaling and root planing using an ultrasonic scaler and standard periodontal curettes. Oral hygiene instructions were given; this includes manual brushing and interdental plaque control using interdental cleaning aids. Oral hygiene was reviewed and if necessary was reinstructed at the second treatment session at 1 month.

In the test site, all pockets irrespective of their initial probing pocket depth (PPD) were additionally treated with chlorhexidine varnish application immediately after mechanical debridement. The varnish was applied with a blunt needle inserted subgingivally and placed in contact with the bottom of the pocket. The varnish was slowly released while the needle was gently moved in a coronal direction. The pockets were deliberately overfilled. The excess varnish was gently removed 15 min following its application using a standard periodontal curette. Each tooth on the test site was subjected to chlorhexidine varnish, application which was repeated on the 4th and the 7th day.

Examination criteria

The following periodontal parameters were recorded in a sequential order at baseline, 1 month, and 3 months after therapy.

Clinical parameters

Gingival index (GI)

The plaque index (PI) Quigley and Hein PI

Bleeding on probing (BoP)

PPD.

Microbial parameters

Anaerobic culturing: Total colony forming units (CFUs).

Microbial sampling and anaerobic culturing

Microbial sampling was done at baseline, 1 month, and 3 months. Anaerobic culturing was done for enumerating the total CFUs.

Supragingival plaque was removed and the tooth carefully dried. A sterile periodontal curette was then inserted into the base to the pocket, in the site with the deepest pocket, and subgingival plaque was removed and transferred to a vial containing 1 ml of transport medium (thioglycolate). The same was repeated on the other side also.

A sample from each site was placed on plates containing enriched trypticase soya agar. These plates were kept in an anaerobic jar (McIntosh Field's anaerobic jar) and incubated at 37°C for 7–10 days. Gas pack system was used to produce anaerobic condition inside the jar. Following 7–10 days of incubation, the total number of CFUs was counted.

The data obtained were subjected to statistical analysis and plotted in the form of tables and bar diagrams.

Statistical analysis

The difference between the preoperative and follow-up measurements of GI, PI, bleeding index, PPD, and clinical attachment level and total CFUs of each patient were computed.

The mean difference between the sites was tested for significance by paired t-test. The mean difference between the sites was tested for significance by independent sample t-test.

Results

The results of this study showed that there was more reduction of GI, PI, BoP, PPD, and total CFUs in the experimental site, compared to control site, at both 1st month and 3rd month.

Chlorhexidine varnish, when used along with scaling and root planing, caused more reduction in GI, PI, BoP, PPD, and total CFUs when compared to scaling and root planing alone.

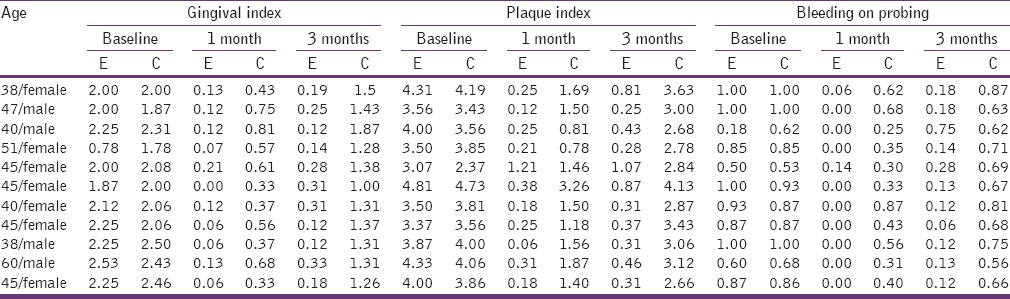

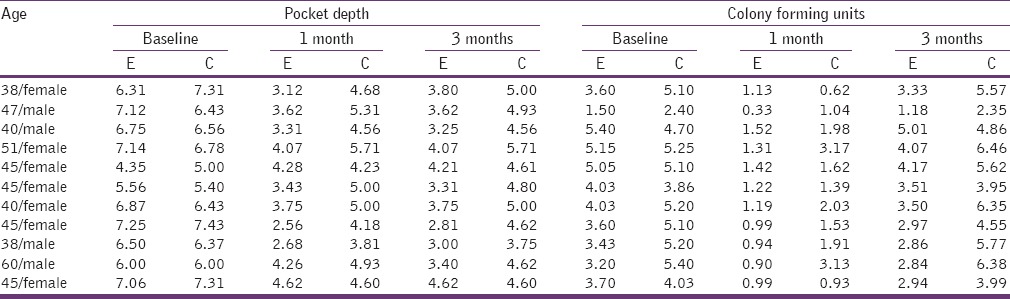

The above results are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Master chart showing gingival index, plaque index, and bleeding on probing

Table 2.

Master chart showing pocket depth and colony forming units

Discussion

The periodontal pocket provides a natural reservoir bathed by gingival crevicular fluid which is easily accessible for application of local antiseptics. The gingival crevicular fluid provides a leaching medium for the release of a drug from the solid dosage form and for its distribution throughout the pocket, making the periodontal pocket, a natural site for treatment with local delivery of chlorhexidine.

Therefore, local administration of antimicrobials subgingivally can be a useful adjuvant to scaling and root planing. Varnishes are the most popular of the sustained release delivery systems applied to the teeth. They are most effective for professional application of chlorhexidine, as they are easy to apply, and they stay in place for a longer time. Balanyk et al.[7] recorded a rapid release of chlorhexidine from thin films of benzoin during the first 24 h, followed by a 10-fold slower, almost linear, release over the next 11–13 days. Calculations revealed that 1.2 mg of chlorhexidine was released during the initial burst. At day 14, the chlorhexidine release ceased and only 3 mg of the total of 10 mg of chlorhexidine had been released. The daily chlorhexidine concentration in the buffer remained above 10 µg/ml, well above the minimal bactericidal concentration (Barry and Sabath 1974).[8]

In the present study, a varnish containing 1% chlorhexidine and 1% thymol, with ethanol and polyvinyl butyral (Cervitec®) was used because of the following reasons put forth by Huizinga and Hennessey et al. It's recommended treatment regimen is 1–3 applications within 10–14 days. Huizinga et al. (1990)[9] tested Cervitec and estimated that only about 20% of the chlorhexidine and thymol was released over a 3-month period. However, a concentration of about 50 µg/ml was maintained constantly, which was higher than the minimal inhibitory concentration of chlorhexidine, i.e., 0.19–2 µg/ml (Hennessey 1973).[10] The authors formulated the following hypothesis for the slow release of the antimicrobial agent.

The first consists of release of chlorhexidine and thymol from the varnish into saliva. Both molecules interact with salivary proteins and salivary bacteria, thus participating directly or indirectly in the reduction of the amount of plaque, and plaque activity as put forth by Schaeken et al., 1989[11] and Petersson et al., 1991.[12]

In a second way, the agents interact with and adhere to the pellicle proteins or other constituents, establishing a reservoir from which chlorhexidine can be slowly released over time.

A diffusion-controlled penetration of chlorhexidine (and thymol) into tooth substances (dentin and cementum) finally represents the third route.[13]

Ardens and Ruben (1993)[14] showed that after a single 24 h varnish treatment of dentin samples, a release rate of 1 µg/cm2 dentin/day was found for a period of up to 6 months.

Yet an intensive application mode seems mandatory to achieve a long-term beneficial effect on gingival health. Indeed, the effects on gingival parameters have not been very convincing following a single varnish administration or even multiple applications within a short time span (Weiger et al.,1994[15], Oggard et al. 1997).[16] It has been reported that repeated application and a longer retention time are required for varnishes with low chlorhexidine concentrations such as Cervitec and Chlorzoin.

Twetman and Petersson (1997)[17] reported that combined treatment with chlorhexidine-thymol and fluoride varnish resulted in a longer effect on interdental plaque samples than a chlorhexidine-thymol varnish alone.

In the present study, there was a significant reduction in the PI, GI, and BoP in the experimental sites, when compared to the control sites. Furthermore, there was an additional reduction in pocket depth and gain in attachment level, in the experimental sites when compared to the control sites.

Few studies have been conducted with the aim of evaluating the effects of chlorhexidine varnish, on clinical parameters such as PI, GI, and BoP.

Shapira et al.[18] studied the effect of applying a chlorhexidine varnish, to a group of mentally retarded patients. The results showed a significant drop in the PI at 4 and 8 weeks in the group treated with chlorhexidine, suggesting similar results to the present study.

Similarly, studies by Valente et al.[19] and Bretz et al.[20] showed a reduction in GI, which was also in accordance with the present study.

Frentzen et al.[21] observed a reduction in the plaque and bleeding index after applying a high-concentration chlorhexidine varnish in a group of young adults. In addition to clinical evaluation, they also conducted microbial evaluation, which showed a reduction in PI and bleeding index, also reduction in Streptococcus colonies. This result was also similar to the results of the present study.

Various studies were conducted to assess the effect of chlorhexidine varnish when used as adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. Dudic et al.[22] conducted a clinical and microbiological evaluation and found only improvement in PI when using the varnish. Weiger et al. (1994).[15] did not detect any significant difference between PI scores recorded at 3 days and 12 weeks after a single 1 h varnish application and no varnish application. Oggard et al. (1997).[16] found a short-term effect on the visual PI scores and the gingival bleeding index scores immediately after varnish treatment. However, over 24 weeks period, no difference could be established. Lack of a long-term antibacterial effect may be explained by the short exposure time and the single application procedure. If the varnish was left in place for as long as it can adhere, the effect might be different.

A series of Studies were conducted by Cosyn et al.[23] to assess the effect of chlorhexidine varnish employed as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in patients with chronic periodontitis. They observed reductions in the treated pockets, obtaining the best results in the pockets that were initially the deepest. There was also improvement in all the clinical parameters such as GI, PI, BoP, PPD, and clinical attachment level. These results were similar to the results obtained in our study.

The present study was conducted to evaluate the clinical and microbiological effects of using Cervitec® as a vehicle for intrapocket delivery of chlorhexidine, in the treatment of chronic periodontitis.

Chlorhexidine varnish has been shown to inhibit the growth of more than 99% of bacterial species isolated from subgingival plaque. In vitro studies by Petersson et al. (1992)[24] designated putative periodontopathogens as being the most sensitive bacteria to chlorhexidine-thymol varnish. Petersson et al. tested the effect of the Cervitec varnish on pure cultures of a series of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as well as yeast. Their results demonstrated Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans as most sensitive and Streptococcus sanguis and Candida albicans as least sensitive. Therefore, chlorhexidine varnish may be promising for the prevention of periodontal disease or as an adjunct to periodontal therapy.

Furthermore, Cosyn and Sabzebar[5] studied the microbiological effect of subgingival application of chlorhexidine following scaling and root planing and found a significant reduction in the levels of Treponema denticola and Tannerella forsythia. In the present study, we evaluated the reduction in total CFUs and found that there was reduced anaerobic count in the test site for up to 3 months. In the present study, also there was a reduction in total CFUs in the experimental site for up to 3 months.

It has not yet been evaluated up to what period of time the varnish is retained to the tooth surface and how this contact time is influenced by brushing technique, interdental cleaning devices, diet, etc., In addition, interference with chemical substances, such as toothpaste components, may not be neglected.

The application of chlorhexidine varnishes seems to have beneficial effects in patients with chronic gingivitis, improving their plaque accumulation and bleeding levels and reducing their GI. It is possible to maintain this beneficial effect for prolonged periods of time although this requires re-application of the varnish. In addition, subgingival application of chlorhexidine varnishes following scaling and root planing gives greater reductions in pocket depth than those obtained solely by mechanical treatment of the pockets.

Conclusion

This study showed that chlorhexidine varnish can be used as an adjuvant to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis.

However, further studies need to be conducted to assess these effects over a long-term, to establish the number of applications and the interval between them that offer the best results over time.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Page RC, Kornman KS. The pathogenesis of human periodontitis: An introduction. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:9–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrera D, Sanz M, Jepsen S, Needleman I, Roldán S. A systematic review on the effect of systemic antimicrobials as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(Suppl 3):136–59. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.29.s3.8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbet EF, Davies WI. The role of supragingival plaque in the control of progressive periodontal disease.A review. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:307–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oosterwaal PJ, Mikx FH, van ’t Hof MA, Renggli HH. Comparison of the antimicrobial effect of the application of chlorhexidine gel, amine fluoride gel and stannous fluoride gel in debrided periodontal pockets. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:245–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosyn J, Wyn I, De Rouck T, Moradi Sabzevar M. A chlorhexidine varnish implemented treatment strategy for chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:750–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinberg D, Rozen R, Klausner EA, Zachs B, Friedman M. Formulation, development and characterization of sustained release varnishes containing amine and stannous fluorides. Caries Res. 2002;36:411–6. doi: 10.1159/000066539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balanky TE, Sandham HJ, Chan D. Dental Varnish for slow intra-oral release of antimicrobial agents. Journal of Dental Research. 1983;62:672. abstract no. 205. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barry AL, Sabath LD. Special tests: Bacterial activity and activity of antimicrobics in combination. In: Lenette EH, Spaulding EH, Truant JP, editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1974. pp. 431–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huizinga ED, Ruben JL, Arends J. Chlorhexidine and thymol release form a varnish system. Journal de Biologie Buccale. 1991;19:343–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennessey TD. Some antibacterial properties of chlorhexidine. Journal of periodontal Research. 1973;(Suppl12):61–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1973.tb02166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaeken MJM, Van der Hoeven JS, Hendriks JCM. Effects of varnish containing chlorhexidine on the human dental plaque flora. Journal of Dental Research. 1989;68:1786–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680121301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersson LG, Maki Y, Twetman S, Edwardsson S. Mutans streptococci in saliva and Interdental spaces after topical applications of an antibacterial varnish in schoolchildren. Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 1991;6:284–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1991.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthijs S, Adriaens PA. Chlorhexidine varnishes: A review. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:1–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arends J, Ruben JL. Chlorhexidine CHX release by dentine after varnish treatment (abstract 88) Caries Research. 1993;27:231–2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wieger R, Friedrich C, Netuschil L, Schlagenhauf U. Effect of chlorhexidine-containing varnish (Cervitec®) on microbial vitality and accumulation of supragingival dental plaque in humans. Caries Res. 1994;28:267–71. doi: 10.1159/000261984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogaard B, Larsson E, Glans R, Henriksson T, Birkhed D. Antimicrobial effect of a chlorhexidine-thymol varnish (Cervitec®) in orthodontic patients.A prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Orofac Orthop. 1997;58:206–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02679961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Twetmans S, Petersson LG. Efficacy of a Chlorhexidine and Chlorhexidine – Fluoride varnish Mixture to decreased Interdental levels of Mutans Streptococcus. Caries Research. 1997;31(5):361–5. doi: 10.1159/000262419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shapira J, Sgan-Cohen HD, Stabholz A, Sela MN, Schurr D, Goultschin J. Clinical and microbiological effects of chlorhexidine and arginine sustained-release varnishes in the mentally retarded. Spec Care Dentist. 1994;14:158–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1994.tb01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valente MI, Seabra G, Chiesa C, Almeida R, Djahjah C, Fonseca C, et al. Effects of a chlorhexidine varnish on the gingival status of adolescents. J Can Dent Assoc. 1996;62:46–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bretz WA, Valente MI, Djahjah C, do Valle EV, Weyant RJ, Nör JE. Chlorhexidine varnishes prevent gingivitis in adolescents. ASDC J Dent Child. 2000;67:399–402, 374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frentzen M, Ploenes K, Braun A. Clinical and Microbiological effects of local Chlorhexidine applications. International dental journal. 2002;5:325–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dudic VB, Lang NP, Mombelli A. Microbiological and clinical effects of an antiseptic dental varnish after mechanical periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:341–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cosyn J, Wyn I, De Rouck T, Collys K, Bottenberg P, Matthijs S, et al. Short-term anti-plaque effect of two chlorhexidine varnishes. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:899–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersson LG, Edwardsson S, Arends J. Antimicrobial effect of a dental varnish, in vitro. Swedish Dental Journal. 1992;16:183–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]