Abstract

Aim:

Curcumin has proven properties such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and it also accelerates wound healing. The purpose of this study was to investigate the level of superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme, in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF), and the impact of nonsurgical treatment on the antioxidant profile using 0.2% curcumin strip as local drug delivery.

Materials and Methods:

A total of twenty subjects of age 35–55 years and 15 subjects with chronic periodontitis, each with bilateral 5–6 mm probing pocket depth, were selected for this study. Healthy group consists of 5 sites in which no bleeding on probing, no pocket depth. Group I – It consists of 15 sites with chronic periodontitis, in which scaling and root planing (SRP) was done (control group). Group II – It consists of 15 sites, in which SRP followed by the placement of curcumin strip inside the pocket (SRP + curcumin strip) (test group). GCF collection was done preoperatively and postoperatively after 21 days. The SOD activity was assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results:

In this study, all the clinical parameters were significantly reduced in test and control sites. Further, SOD levels were significantly improved in test sites when compared with control sites.

Conclusion:

Thus, the present study concluded that curcumin strip can be effectively used as an adjunct to SRP in treatment of chronic periodontitis and serves as antioxidant in subgingival environment.

KEY WORDS: Curcumin, periodontitis, superoxide dismutase enzyme

Periodontal disease is a common, chronic inflammatory condition and has a multifactorial etiology, with primary etiological agents being pathogenic bacteria in the subgingival area. The standard periodontal therapy is with the objective of reducing the total bacterial load and changing the environmental conditions of the microbial niches. Although mechanical debridement (scaling and root planing [SRP]) reduces the level of subgingival bacteria, it does not eliminate all the pathogens which reside deep in connective tissue which destroys the bone.[1]

To overcome the limitations of this conventional treatment, chemical agents such as antibiotics and antiseptics have been used successfully to treat moderate to severe periodontal diseases.[2] For the shortcomings of systemic administration such as bacterial resistance and drug interactions, local delivery systems containing antibiotic or antiseptic agents were introduced.[3] Various locally delivered agents that are successfully used include tetracycline fibers,[4] 10% doxycycline,[5,6] 2% minocycline,[7] metronidazole,[8] and chlorhexidine gluconate,[9] but none is without side effects. Research is being conducted for the use of the natural products instead of chemical agents. Medicinal plants have been used as a traditional treatment agent for numerous human diseases since ages in many parts of the world. One such natural product which holds medicinal value is turmeric (Curcuma longa).[10]

Curcumin has proven properties such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, hepatoprotective, immunostimulant, antiseptic, antimutagenic, and it also accelerates wound healing.[11] Curcumin is the principal curcuminoid of the popular Indian spice turmeric, which is a member of the ginger family (Zingiberaceae). The other two curcuminoids are desmethoxycurcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin.[12] Reactive oxygen species (ROS) include oxygen-derived free radicals, such as superoxide (O2−), hydroxyl (OH), nitric oxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hypochlorous acid (HOCl). This oxidative stress phenomenon is believed in part to be responsible for the inflammatory conditions affecting the periodontium, manifesting as gingivitis and periodontitis.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the level of superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme, in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF), and the impact of nonsurgical treatment on the antioxidant profile using 0.2% curcumin strip as local drug delivery.

Materials and Methods

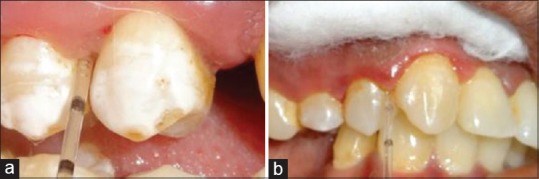

A randomized split mouth-controlled clinical study was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of curcumin strip in the treatment of chronic periodontitis compared to SRP alone. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Board. The study-related procedures were explained to the patients before they signed an informed consent form. A total of twenty subjects of age 35–55 years and 15 subjects with chronic periodontitis, each with bilateral 5–6 mm probing pocket depth (PPD), were recruited from the outpatient Department of Periodontics, J.K.K. Nattraja Dental College and Hospital, Komarapalayam, Tamil Nadu, India. Patients who received treatment with any form of antibiotics/anti-inflammatory drugs in the last 3 months, smokers, and with history of systemic diseases, pregnancy, lactation, and drug allergies were excluded from this study. A composition of 0.2% curcumin was loaded onto the guided tissue regeneration (GTR) membrane (Heali Guide – Advanced Biotechnology) and was used in strip form as shown in Figure 1. Preoperative probing depth was measured and gcf sample was collected preoperatively as shown in Figures 2 and 3 respectively.

Figure 1.

0.2% loaded curcumin strip

Figure 2.

Preoperative (probing pocket depth mm)

Figure 3.

Gingival crevicular fluid collection. (a) Control group, (b) Test group

Criteria for grouping

Healthy group: It consists of 5 sites in which no bleeding on probing, no pocket depth (Healthy group)

Group I: It consists of 15 sites, in which SRP was done (control group)

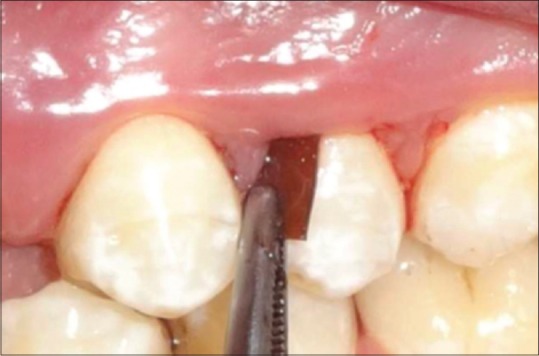

Group II: It consists of 15 sites, in which SRP was followed by the placement of curcumin strip inside the pocket (SRP + curcumin strip) (test group) as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Curcumin strip placement

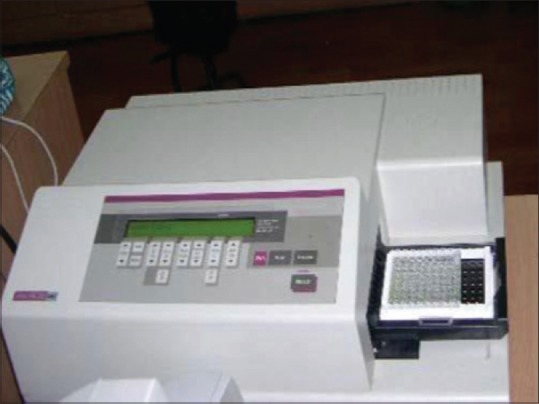

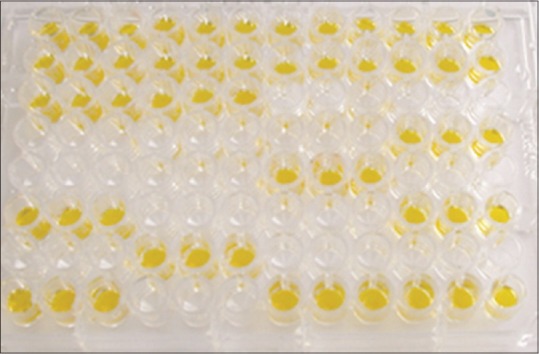

GCF collection was done using micropipettes preoperatively and postoperatively after 21 days as shown in Figure 3. Postoperative probing depth was measured as shown in Figure 5. The SOD activity was assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as shown in Figures 6 and 7. The clinical parameters such as plaque index (PI), gingival index (GI), and sulcus bleeding index (SBI) were assessed at baseline and on the 21st day.

Figure 5.

Postoperative (probing pocket depth mm)

Figure 6.

Laboratory analysis

Figure 7.

Results of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Results

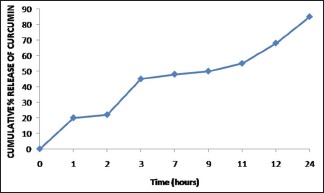

The results obtained were analyzed statistically, and comparisons were made within each group using paired and unpaired Student's t-test using (IBM Corp. Released 2010. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). A value of P < 0.05 was considered as the level of significance. The in vitro release of curcumin from the collagen membrane was over 24 h as shown in Graph 1.

Graph 1.

The in vitro release of curcumin from the collagen membrane over 24 h

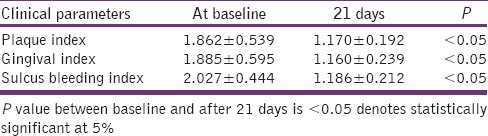

The PI, GI, and SBI scores at baseline was 1.862 ± 0.539, 1.885 ± 0.595, 2.027 ± 0.444, respectively, and after 21 days, PI, GI, and SBI scores were reduced to 1.170 ± 0.192, 1.160 ± 0.239, 1.186 ± 0.212, respectively, as shown in Table 1 and Graph 2. Comparison of the PI, GI, and SBI scores between baseline and after 21 days shows a statistically significant difference with a P < 0.05 in both test and control groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical parameters at baseline and after 21 days

Graph 2.

Comparison of mean changes in clinical parameters at baseline and on the 21st day

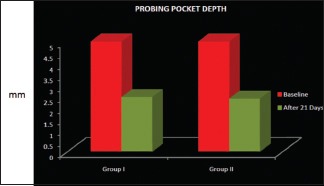

The PPD in Group I at baseline was 5.0 ± 0.0 mm, and the PPD after 21 days reduced to 2.467 ± 0.833 mm. The PPD in Group II at baseline was 5.0 ± 0.0 mm, and the PPD after 21 days reduced to 2.400 ± 0.828 mm. Comparison of the PPD in Groups I and II shows that statistically, there is no significant difference with a P > 0.05 as shown in Table 2 and Graph 3.

Table 2.

Comparison of probing pocket depth between Group I and Group II

Graph 3.

Intergroup comparison of mean changes of probing pocket depth in Groups I and II

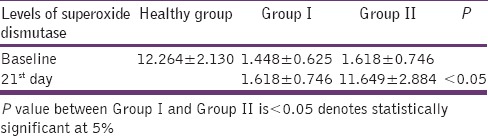

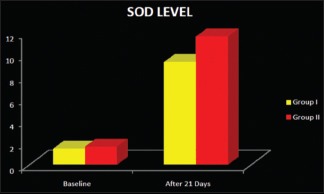

In the healthy group, the mean concentration of SOD levels was 12.264 ± 2.130. In the control group, at baseline, the SOD level was 1.448 ± 0.625 and 21 days after treatment SOD level improved to 9.366 ± 2.609. In the test group, the SOD level at baseline was 1.618 ± 0.746 and 21 days after treatment SOD level improved to 11.649 ± 2.884 as shown in Table 3 and Graph 4. Comparison of SOD levels postoperatively in both groups showed that there is a statistically significant difference with a P < 0.05.

Table 3.

Comparison of superoxide dismutase levels between groups

Graph 4.

Intergroup comparison of superoxide dismutase enzyme levels

Discussion

Periodontal disease is a multifactorial disease caused by microbial flora, which is present in the subgingival plaque. These bacterial species result in the production of various cytokines and also causes an increase in number and activity of polymorphonucleocytes (PMNs). PMNs produce ROS superoxide via the respiratory burst mechanism. ROS have deleterious effects on tissue cells when produced in excess.

Curcumin is a yellow pigment from C. longa and is a major component of turmeric.[13] The desirable preventive or putative therapeutic properties of curcumin have also been considered to be associated with its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and chemopreventive properties. The anti-inflammatory effect of curcumin is most likely mediated through its ability to inhibit cyclooxygenase-2, lipoxygenase, and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Curcumin may function indirectly as an antioxidant either by inhibiting the activity of inflammatory enzymes or by enhancing the synthesis of glutathione, an important intracellular antioxidant. Curcumin also acts as a free radical scavenger and antioxidant by inhibiting lipid peroxidation and oxidative DNA damage.[14] Currently, there is a growing interest in the linkage between antioxidants and periodontal disease. A significant antioxidant enzyme within mammalian tissues is SOD, which catalyzes the dismutation of O2− to H2O2 and O2.

Hence, curcumin possessing the antioxidant activity is used in this present study. Efficacy of 0.2% curcumin loaded onto the GTR membrane in strip form adjunct to SRP was evaluated in the present study. According to Franz diffusion method,[15] maximum release of drug from strip used in this study was within 24 h.

In our present study, the clinical parameters such as PI, GI, and SBI scores were reduced from baseline to 21st day in both test and the control groups. This is in accordance with the study conducted by Behal in 2001.[11] The mean PPD was significantly reduced on the 21st day compared to the baseline in both test and control groups. There is no significant difference between the control and test groups. The results were in accordance with the study conducted by Behal et al. in 2011,[11] who demonstrated PPD reduction following placement of 2% turmeric gel, when compared to SRP alone.

GCF samples were taken at baseline and after SRP (21st day). In the healthy group, SOD levels were 12.264 ± 2.130. In the control group, at baseline, SOD level was found to be 1.448 ± 0.625 and improved to 9.366 ± 2.609 on the 21st day following periodontal therapy, which shows statistically significant differences before and after treatment in accordance with Karim et al. 2012.[16] SOD level at baseline in the test group was 1.618 ± 0.746 and improved to 11.649 ± 2.884 on the 21st day following periodontal therapy. On comparison of SOD levels, Group II showed statistically significant difference comparing to Group I. The SOD levels seem to be nearing to the healthy group when curcumin strip was used as an adjunct to SRP.

Summary and Conclusion

From this study, all the clinical parameters were significantly reduced in test and control sites. Furthermore, SOD levels were significantly improved in test sites when compared with control sites. Thus, the present study concluded that curcumin strip can be effectively used as an adjunct to SRP in treatment of chronic periodontitis and serves as antioxidant in subgingival environment. Although the study has positive outcome for particular antioxidant, elaborate studies are needed to prove the efficacy of curcumin strip in other antioxidants and also with reference to areas such as proper concentration and release system.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cobb CM. Non-surgical pocket therapy: Mechanical. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:443–90. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodson JM. Antimicrobial strategies for treatment of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 1994;5:142–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenstein G, Polson A. The role of local drug delivery in the management of periodontal diseases: A comprehensive review. J Periodontol. 1998;69:507–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.5.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodson JM, Tanner A. Antibiotic resistance of the subgingival microbiota following local tetracycline therapy. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1992;7:113–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1992.tb00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larsen T. Occurrence of doxycycline resistant bacteria in the oral cavity after local administration of doxycycline in patients with periodontal disease. Scand J Infect Dis. 1991;23:89–95. doi: 10.3109/00365549109023379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Javali MA, Vandana KL. A comparative evaluation of atrigel delivery system (10% doxycycline hyclate) Atridox with scaling and root planing and combination therapy in treatment of periodontitis: A clinical study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:43–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.94603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steenberghe VD, Bercy P, Kohl J. Subgingival minocycline hydrochloride ointment in moderate to severe chronic adult periodontitis: A random, double blind, vehicle controlled, multicenter study. J Periodontol. 1993;64:637. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stelzel M, Florès-de-Jacoby L. Topical metronidazole application compared with subgingival scaling.A clinical and microbiological study on recall patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:24–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soskolne WA, Heasman PA, Stabholz A, Smart GJ, Palmer M, Flashner M, et al. Sustained local delivery of chlorhexidine in the treatment of periodontitis: A multi-center study. J Periodontol. 1997;68:32–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagpal M, Sood S. Role of curcumin in systemic and oral health: An overview. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2013;4:3–7. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.107253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behal R, Mali AM, Gilda SS, Paradkar AR. Evaluation of local drug-delivery system containing 2% whole turmeric gel used as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in chronic periodontitis: A clinical and microbiological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:35–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.82264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullaicharam AR, Maheswaran A. Pharmacological effects of curcumin. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis. 2012;2:92–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akram M, Uddin S, Ahmed A, Usmanghani K, Hannan A, Mohiuddin E, et al. Curcuma longa and curcumin: A review article. Rom J Biol Plant Biol. 2010;55:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gowri R, Narayanan N, Maheswaran A, Harshapriya G, Mathachan S. Curcumin – a salubrious asset to immune system. Int J Pharm Rev Res. 2014;4:75–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baert B, Boonen J, Burvenich C, Roche N, Stillaert F, Blondeel P, et al. A new discriminative criterion for the development of Franz diffusion tests for transdermal pharmaceuticals. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2010;13:218–30. doi: 10.18433/j3ws33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karim S, Pratibha PK, Kamath S, Bhat GS, Kamath U, Dutta B, et al. Superoxide dismutase enzyme and thiol antioxidants in gingival crevicular fluid and saliva. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2012;9:266–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]