Abstract

Over the past few years a number of strategic initiatives to improve catheter management and reduce associated infections have been introduced. This paper details the introduction of a patient-held catheter passport and an improved documentation record using the PDSA (Plan, Do, Study, Act) cycle of change implementation in one large acute National Health Service (NHS) trust and local health economy (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2008)

Keywords: Infection prevention and control, healthcare-associated infections, urinary catheterisation, urinary tract infections

Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTI) account for almost one in five healthcare associated infections (HCAIs) (17.2%). More than 40% of those affected have had a urinary catheter fitted in the preceding seven days. Driving down urinary catheter use may therefore be key in reducing UTI (Health Protection Agency, 2011).

Currently, about a quarter of the nine million people treated in the NHS are catheterised at some time during their treatment (Nzarko, 2009). Evidence suggests that in many cases this is unnecessary and exposes patients to a significant risk of infection. On average a UTI acquired in hospital extends a patient’s stay by five to six days and costs the healthcare provider £1,327 to treat (Plowman et al, 1999; Foxley, 2011).

Infection rates increase for every extra day a urinary catheter remains in place. To reduce the number of catheter associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), practitioners should: avoid inserting catheters when it is unnecessary; use evidence-based practice for ongoing care; and promptly remove the catheter as soon as clinically indicated (Ward et al, 2010).

Implementation

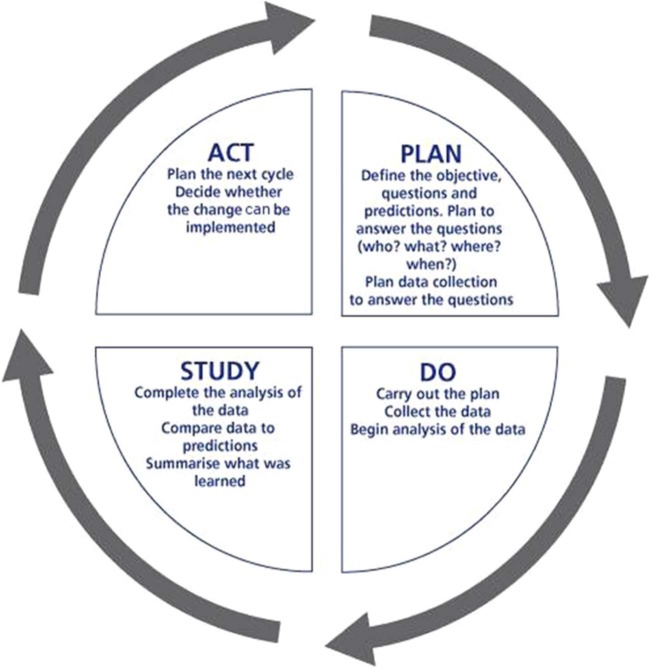

This article will discuss two strategies – implementation of the catheter passport, and the urinary catheter assessment form. To test the robustness of these strategies and the success of the implementation plan, the framework PDSA was used as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PDSA cycle of change implementation

1. Plan

The idea of the catheter passport initially came from one of the elderly care consultants within the trust, at a multidisciplinary infection control update. The aim was to produce the passport in a patient-centred style and for it to be a hand-held document for the patient, in order to improve the quality and experience of care for those who were catheterised. The government aims for a ‘no decision without me’ strategy, ensuring patients are provided with sufficient information and are clear about the available continence-management options, so that they can make informed choices about their care (Department of Health, 2012). Patients involved in the decision-making process are more likely to comply with their treatment and the management of their care, thereby achieving more positive outcomes.

Use of the catheter passport is intended to ensure a quality-driven, patient-focused service, delivering better outcomes and reduction in costs as the patient passes from one healthcare professional to another. A single patient record across the health economy would reduce variation in practice and provide documentation of the whole patient journey.

The decision was taken to develop the passport in a similar style to the warfarin books, which are pocket sized and made of quality durable paper. The chosen colour of the passport was yellow, as this colour was often used to depict the infection control department. It was devised in collaboration with the elderly care consultants, the corporate nursing team, the urology clinical nurse specialists, the infection prevention nurses from across three health economies and the infection prevention control team (IPCT) at the trust. A number of meetings were held for community and care home staff in order to allow their input in the catheter passport design.

Telefex, which supplies the trust with urinary catheters and has previously supported infection control projects, was approached to assist with the printing and design of the passport. They readily agreed to give their support.

The passport includes:

Patient information. Demographic details and contact numbers for general practitioner and district nurse.

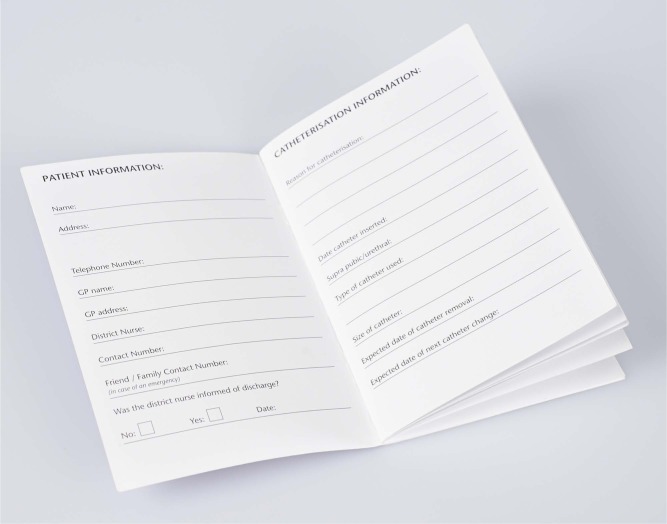

Catheterisation information. Comprising the reason for catheterisation and details of insertion. There are five pages to allow a separate entry for each catheter insertion/change. See Figure 2.

Dos and Don’ts. This includes the importance of drinking plenty of fluid and not touching the end of the leg bag connector, to prevent the risk of infection.

When to call a healthcare professional. Advice for patients and carers as to when to contact the doctor/nurse. This includes situations such as foul smelling urine, pain in abdomen or back.

Hand-washing guide. A pictorial step by step guide of when and how to decontaminate hands.

Useful websites and addresses, such as the Department of Health.

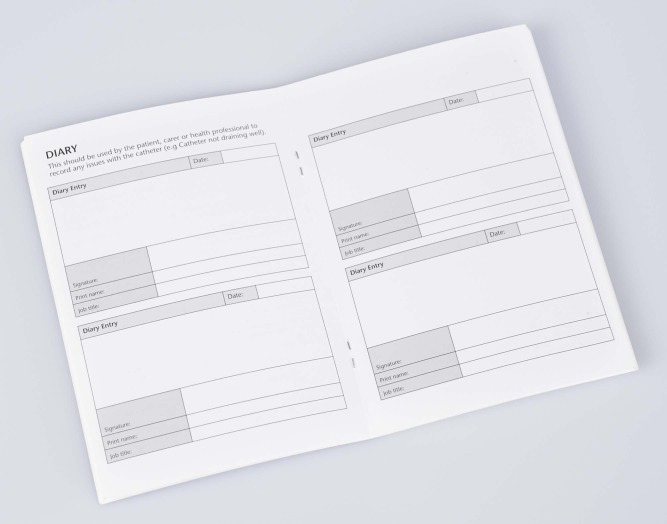

Patient diary. This incorporates 36 entries for the carer, patient or healthcare professional to record any issues with the catheter. This facilitates continuity of care as the patient passes from one environment to another. See Figure 3.

Figure 2.

An example of catheter details inside the passport

Figure 3.

An example of the patient diary inside the passport

The aim of the catheter passport is to provide a means of monitoring the timely catheter reviews that take place and of recording them in the patient’s diary. This ensures that the correct catheter is in place and will be removed as soon as possible. It was decided that six months was an appropriate time scale to test the project and analyse what was required to fully implement the project across the trust.

Patients’ feedback is important, so a semi-structured patient experience questionnaire was devised. This was sent out to patients and followed up by a telephone call from the infection prevention and control nurse (IPCN). Feedback was also sought from ward staff at relevant meetings.

The passport was endorsed by the trust’s Nursing and Midwifery Board with executive and patient safety team support. This helped to raise its profile. The passport was then launched throughout the trust. It also featured in a poster presentation at Infection Prevention 2011, enabling it to be promoted nationally to other hospitals.

2. Do

It was decided to trial the catheter passport within ten specific wards, all located within the same hospital because of the links that the IPCT had within that community. Staff in ward areas were encouraged to give out the passports to patients being discharged with a catheter and to commence a passport for patients who had been admitted to the trust with a long-term catheter. Staff were asked to complete a separate proforma indicating the name and hospital number of any patient issued with a passport. The form was then sent to the IPCT to enable those patients to be followed up.

A launch meeting was arranged in order to discuss the passport with staff within the community. The value of the passport was recognised by the commissioners and compliance is included as a key performance indicator for the trust in the 2013/2014 framework. Following discussion at a local health economy meeting, it was agreed to launch the passport with patients across a range of healthcare providers. One of the problems encountered was engagement with the nursing care homes and residential homes. To improve this the catheter passport regularly features in the trust’s community newsletter. Enquiries have been received from interested colleagues.

3. Study

Overall, feedback from the patients was very positive. One of the patients commented, “the catheter passport made me feel involved in my care of my catheter.” At first the staff felt it was yet another piece of paper to complete, but after further education about the project, their feedback was also very positive. Many members of staff remarked that the colour of the passport was too similar to the warfarin book. It became evident that passports had been distributed but few names had been passed to the IPCT team to enable follow up.

4. Act

To improve compliance a staff incentive initiative was introduced, providing a prize to staff members who had given out a passport. This had the desired effect of patient names being completed. The colour of the passports was changed to purple. To encourage the patients to bring the passport into hospital a reminder was added to the front cover.

To address the issue of the lack of awareness of the passport, it was important to cascade this message out to the ward staff. It was decided to do a ward-based teaching session to staff on all wards, so that they will have better understanding of the use and merits of the catheter passport. The presentation was kept short, as there was an awareness of the possibility of the sessions being cancelled due to workload issues. Previous studies have shown that ward-based teaching overcomes staffing pressures (Richardson, 2001). This session is incorporated into the mandatory infection control training and during the infection control link workers’ study days. The PDSA cycle was repeated throughout the project, with minor adjustments being made to the passport after staff feedback.

Catheter assessment monitoring form

In 2008 a trust-wide review was undertaken that provided a snapshot of each individual ward, identifying which patients were catheterised at that time. Any inadequate documentation leads to the ward being issued with a catheter improvement notice. Ultimately, this benefits direct patient care and may reduce the number of CAUTIs. Subsequent audits were carried out quarterly and the results sent to the ward managers. These audits demonstrated an ongoing need to improve documentation in relation to urinary catheter care, in particular, that catheters are not inserted unnecessarily. An example of this was the insertion of a catheter to a patient to manage risk of falls.

In 2009 the Chief Nursing Officer for England launched the high impact actions protection from infections strategy. This focuses on the essentials of care and advocates a bundle approach to minimising the risk of CAUTI (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2009).

In order to implement this strategy, a group representing all grades of staff was set up at the trust. Healthcare Assistants (HCAs) were chosen as catheter champions and feedback from the group shows how they had introduced systems to implement evidence-based practices for ongoing catheter care. HCAs are a crucial group of staff for promoting improvement in this field. With appropriate support, including enhancing their knowledge through education, peer support and mentorship, they are confident enough to challenge the need for a patient to have a catheter inserted and question why it needs to remain in place (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2009).

To replace the existing care plan, a catheter assessment form was developed as part of these high impact action groups. The trust care plan needed updating due to perceived difficulties in staff completing it. There was also no procedure in place for prompt removal of catheters.

The new form is adapted from the urinary catheter monitoring form developed by the Winchester and Eastleigh Trust and is used to record and document all catheter insertions and ongoing urinary catheter care. A simple checklist to support early removal acts as a prompt for daily review of the catheter with a view to preventing unnecessary catheterisation.

The form provides one sheet of paper to view a 28-day history of the patient’s catheterisation journey including indicators, such as when the bag was removed or changed and when the catheter was reviewed. It also provides documented evidence of catheter hygiene. Its intention is to empower nurses to challenge the reason why the catheter was inserted. Nurses who carry out catheterisation not only need to ensure ongoing care is of the highest standard but also to ensure that there is a clinical need for catheterisation in the first place (Ward et al, 2010). The new documentation form was initially trialled on elderly and trauma wards.

Discussion

Since 2004 there has been a Department of Health directive to monitor and report all cases of meticillin resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) bacteraemia within England. In 2012/2013 MRSA bacteraemia at the trust has been reduced by 12.5% compared with the previous year. Over 25% of the reportable MRSA bacteraemia at the trust were attributable to urosepsis as a result of the patient having a long-term urinary catheter. However, it is too early to quantify the role of the passport in reducing these figures. Urinary catheters remain a focus for these infections across the health economy. Going forward, with a zero tolerance approach, it is essential that any avoidable bacteraemia related to urinary catheters does not occur.

In 2006, NHS trusts in England signed up to a number of initiatives, including the introduction of a strategic programme set by government. This consists of implementing the Saving Lives: Reducing Infection and Delivering Safe Care document (Department of Health, 2007), which provides a suite of tools and techniques known as High Impact Interventions for acute trusts to help achieve sustainable reductions in HCAIs. One of these focuses on promoting best practice in relation to CAUTI. Infection control link workers within the trust were assigned to perform these audits owing to their interest in and enhanced knowledge of infection prevention practices. Damani (2003) has shown that establishing competent infection control link workers can motivate staff and more effectively improve practice. Link staff input audit outcomes on to a database, which displays results on the infection control notice board for all staff to see.

In July 2011, the safety thermometer was introduced to hospitals. This provides a simple method for surveying patient harm and analysing results so that hospitals can measure and monitor local improvement and harm-free care (Power, 2011). Included within the safety thermometer, is the identification of the number of catheters in place and associated UTIs.

An ongoing issue identified during implementation of these strategies was poor communication between the hospital and community teams. Both are unaware of the timing for changing of catheters and of the problems experienced by some patients with long-term catheters. This made catheter assessment and timely removal difficult. Feedback from patients indicated that they did not receive sufficient information relating to their urinary catheters. This is an area of patient care that we needed to address. With this in mind in 2010 a patient-held record (catheter passport) was developed.

Implementing change is a challenging process; for a successful outcome the methodology used needs to be clear and as simplistic as possible. to enhance Resistance to change often results from tension among those involved and a poor communication strategy (Makinson, 2001). Arguably the most important challenge for IPCT is to overcome the reluctance of individuals to change their behaviour (Fraise, 2009). Difficulties arose in implementing change with some staff as there was a perception that this added to their workload but further education to provide a better understanding of the benefits of the passport helped overcome this. Staff indicated that patients would not comply and would not bring passports back into hospital. Verbal feedback has been received from nursing staff to confirm that patients are not only complying with the passports but are bringing them when attending hospital visits.

Use of the Quality Improvement Cycle is successful on many levels. The pilot project was successful in gaining support from the staff. To improve the process, the message still needs to be communicated to staff about all the initiatives involved in improving catheter management and regular updates provided. This is being done via the trust intranet, corporate newsletters, infection control boards displayed in wards and departments, and continuing with the ward-based teaching. Plans are now in place following the pilot and the changes that were made using the PDSA cycle to roll out the passport and documentation across the trust and local health economy. Effectively putting these initiatives into practice will further reduce HCAIs.

It is anticipated that there will be a noticeable reduction in the rates of staphylococcus bacteraemia linked to CAUTI.

Reducing HCAI rates will help restore public confidence in the health service and reassure patients that our hospitals are clean and safe places to be treated, and in addition it will save money and release bed days (Stevens, 2006). In view of current heightened public concerns in the wake of much media attention such as the Francis Report (Mid Staffordshire, 2010) we believe that involving the patient and restoring their confidence is a vital and important part of this initiative.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of conflicting interest: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Damani N. (2003) Manual of infection control procedures. 2nd edn. Medical Media Limited: Greenwich, London. [Google Scholar]

- Department Of Health. (2007) Saving lives: reducing infection, delivering clean and safe care. Department of Health: London [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. (2012) Health and Social Care Act. Liberating the NHS: no decision about me, without me. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/156256/Liberating-the-NHS-No-decision-about-me-without-me-Government-response.pdf.pdf (accessed 15 January 2013).

- Foxley S. (2011) Driving down catheter associated infection rates. Nursing Times 107(29): 14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraise A. (2009) Ayliffe’s control of healthcare associated infection. 5th edn. Fraise Adam, Bradley Christina. (eds). Edward Arnold (Publishers) Ltd: London. [Google Scholar]

- Health Protection Agency. (2011) English national point prevalence survey on healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use, 2011. Preliminary data. http://www.hpa.org.uk/webc/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1317134304594 (accessed 15 March 2013).

- Makinson G. (2001) Managing change. Nursing & Residential Care 3(12): 596–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. ‘The Francis Report’. (2010) http://www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/report (accessed 28 October 2013).

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. (2008) Quality and service improvement tools. http://www.institute.nhs.uk/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/plan_do_study_act.html (accessed 15 March 2013).

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. (2009) High impact actions for nursing and midwifery. NHS 111: Coventry. [Google Scholar]

- Nzarko L. (2009) Providing effective evidence-based catheter management. British Journal of Nursing 18(7): S4–S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plowman R, Graves N, Griffin M, Roberts JA, Swan A, Cookson B, Taylor L. (1999) The socio-economic burden of hospital acquired infection. Public Health Laboratory Service: London. [Google Scholar]

- Power M. (2011) The imperative to improve safety in NHS healthcare organisations. Nursing Management 17(9): 28–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J. (2001) Post operative epidural analgesia: introducing evidence-based guidelines through an education and assessment process. Journal of Clinical Nursing 10: 238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. (2006) Improving reliability, safety and cleanliness. Nursing Management 12(10): 14–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward L, Fenton K, Maher L. (2010) The high impact actions for nursing and midwifery 5: protection from infection. Nursing Times 106(31): 20–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]