Abstract

The Centre for Behaviour Change at University College London (UCL) is a new venture that has grown out of the work that we have been doing in the Health Psychology Research Group at UCL and seeks to harness the different pockets of behaviour change work in different disciplines across UCL. A lot of our work in health focuses on the adoption of evidence-based guidelines in practice; not just designing and evaluating interventions, but also developing usable tools for people who are tasked with changing behaviours. These tools aim to enable those who do not necessarily have a background in behavioural science to understand the behaviours they are trying to change and design appropriate interventions.

Keywords: behaviour, healthcare-associated infections, implementation science, research

Designing interventions to change behaviour

Designing interventions directed at behaviour change is key to effective infection prevention control. An example is the UK Five Year Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy (Department of Health, 2013); the first three areas in this are: improving hygiene practices; tackling overuse or false prescription of antimicrobials; and increasing adherence to evidence-based guidelines. All these are behaviours so if we want to tackle them we need to design effective interventions to change them. However, while we generally acknowledge the need for specific knowledge and specialist skills in order to perform a wide range of tasks from heart surgery to building bridges, when it comes to changing behaviour it tends to be different. This is because we all behave in certain ways and see other people behave, we then form our own theories about what it might take to change behaviour and these are not always right. Despite the existence of a science of behaviour change, it is not always applied and interventions are often designed according to the ‘It Seemed Like A Good Idea At The Time’ (ISLAGIATT) principle. This means that we jump straight to intervention and crucially miss out understanding the behaviours we are trying to change, what is maintaining and initiating these behaviours, and what might be a facilitator to enabling the desired behaviour. Theoretical frameworks that integrate a wide range of psychology theories about behaviour allow us to analyse the behaviours and the context in which they occur and then design appropriate interventions based on this analysis.

Diagnosing behaviours that need to be changed

However, a key starting point is being precise about the behaviours that we are trying to change. Evidence-based guidelines are not particularly explicit about who needs to do what, where and when. Being more specific about what we are trying to change allows us to be more focused when it comes to understanding these behaviours, since what might prevent staff using gloves might be completely different from what prevents them from engaging in hand hygiene practice. Designing effective interventions therefore means making a ‘diagnosis’ of the behaviours that need to be changed and this requires a systematic analysis of why the behaviours happen and what needs to change for the desired behaviour to occur. The COM-B model provides a simple tool to support this analysis. This model is based on the principle that for a behaviour to occur there are three conditions that need to be in place. First, capability, that is the psychological and physical ability to perform the behaviour, to know what to do and how to do it. Second, we need motivation because if we do not care about it we are not going to do it. Motivation can be divided into reflective processes, which are focused on a cost–benefit analysis about whether we think something is worthwhile doing, and automatic processes, which are the emotional reactions, wants and needs and habits to what we are doing. Finally, we need the opportunity, the environment needs to be conducive to that behaviour. This is influenced by physical components, having the appropriate resources such as time and money, and the social environment, the cultural context that governs our everyday behavioural norms. This simple tool can help us to start making sense of what might be driving a barrier to behaviour. The next step is to link the theoretical analysis of behaviour in context to the design of an intervention.

The Behaviour Change Wheel: a framework to guide intervention design

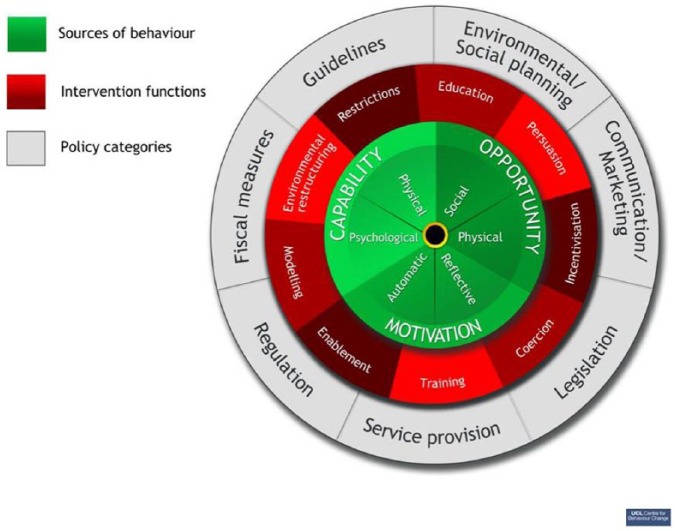

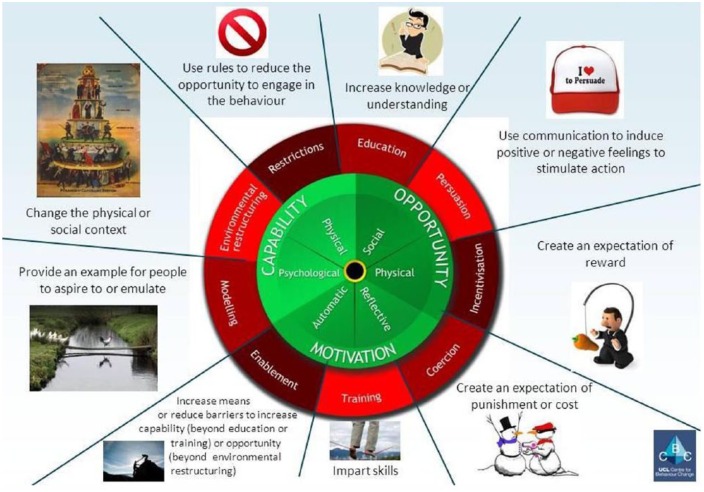

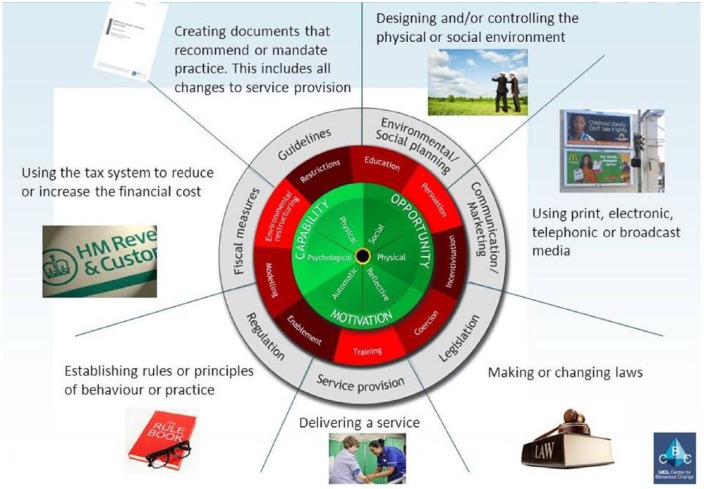

For a framework to be effective in guiding intervention design it is essential that it is comprehensive (considers all the important options to change behaviour), coherent (it uses a systematic method to select relevant options) and linked to a model of behaviour that is usable to those who need it. Michie et al. (2011) systematically reviewed the literature to identify 19 behaviour change frameworks and, by synthesising these frameworks, designed a new one that met all these criteria. This is called the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) and it includes the COM-B model as its hub (Figure 1). The review of the evidence identified nine categories of ‘intervention functions’ that can be applied in order to change behaviour such as education, persuasion, coercion and so on (Figure 2). Why functions? Well, we know that one intervention can serve more than one function. For example, a road safety campaign might serve the function of educating drivers about the difference between hitting somebody at 40 mph versus 30 mph but by using imagery to demonstrate the impact on a child hit by a car at 40 mph, the intervention also serves the function of persuading drivers to change how they feel about the behaviour. The final component of the BCW is the policy categories that might be used to deliver the intervention. These were derived from a synthesis of the findings of the systematic review and range from guidelines, through to communication/marketing, legislation and regulation (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

The Behaviour Change Wheel. Source: Michie et al., 2011. © 2011 Michie et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

Figure 2.

Categories of intervention functions. Source: Michie et al., 2011. © 2011 Michie et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

Figure 3.

Policy categories for delivering interventions. Source: Michie et al., 2011. © 2011 Michie et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

For those working on the frontline there is often little time and very little resources to design interventions. The COM-B model can be used in a structured discussion around the table to consider whether capability, opportunity or motivation need to change to make the behaviour you are trying to change more likely. The BCW can then be used to systematically select appropriate intervention functions and policy categories to bring about change. However, since there are any number of ways in which a particular intervention can be approached, the active ingredients in an intervention function that are likely to bring about the desired change need to be specified. In 2013, an international group of implementation researchers published a general taxonomy of behaviour change techniques which describes 93 different actions to change behaviour (Michie et al., 2013). These are clustered under headings including goals and planning or identity and each of the techniques has an agreed label, an agreed definition and an example. This work is important as it represents a consensus of the language that can be used to describe behaviour change. It provides a ‘shopping list’ of strategies that can be used to change behaviour and which can then be linked to the intervention functions and policy areas identified in the BCW. In order to select the optimal intervention functions for a particular context the APEASE criteria can be used to make decisions in a systematic and comprehensive way (Table 1). A step-by-step guide can be found in The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing (Michie et al., 2014).

Table 1.

The APEASE criteria.

| Criteria | Question? |

|---|---|

| Affordability | Can it be delivered to budget? |

| Practicability | Can it be delivered as designed? |

| Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness | Does it work (ratio of effect to cost)? |

| Acceptability | Is it judged appropriate by relevant stakeholders (publicly, professionally, politically)? |

| Side-effects/safety | Does it have any unwanted side-effects or unintended consequences? |

| Equity | Will it reduce or increase the disparities in health/wellbeing/standard of living? |

An example of the BCW in practice

Increasing compliance with hand hygiene is a key IPC goal, but despite clear guidelines we know that implementation of these guidelines is suboptimal. The CleanYourHands campaign is an example of an implementation intervention which, if viewed through the lens of COM-B, was targeting opportunity by making alcohol handrub available at every bedside and targeting motivation through persuasive posters encouraging patients to ask. However, it could be argued that it did not target the psychological capability to pay attention to cleaning hands over a myriad of other competing behaviours, to develop routines for noticing when that behaviour has not happened, and to develop plans for acting in the future. So we designed a ‘bolt-on’ to the CleanYourHands campaign based on self-regulation or control theory which involves setting goals and monitoring behaviour (Carver and Scheier, 1982). This was achieved at both individual staff and ward level by giving immediate feedback on 20 min audits of hand hygiene practice against the local guideline. A certificate was given if compliance was 100%, otherwise the observer worked with them to develop individual or ward level goals and an action plans. The results of this was the use of soap and alcohol rub tripled, infection rates decreased, and crucially the individual feedback led to staff being 13–18% more likely to clean their hands (Fuller et al., 2012). This example demonstrates the translation of theory about behaviour into the functions we want our interventions to serve and the particular techniques that are going to bring about that change and then seeing a tangible and significant change in behaviour.

In conclusion

The COM-B model enables us to start the process of behaviour change by being specific about the behaviours we are trying to change and then to understand the behaviour in the context in which it occurs. The BCW can then be used to systematically select appropriate intervention functions and policy categories based on what we have understood about the behaviour and, by considering options in the behaviour change taxonomy, to specify the active ingredients for implementing effective change.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Peer review statement: Not commissioned; blind peer-reviewed.

References

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. (1982) Control theory: a useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin 92: 111–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2013) UK Five Year Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2013 to 2018. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/244058/20130902_UK_5_year_AMR_strategy.pdf.

- Fuller C, Michie S, Savage J, McAteer J, Besser S, Charlett A, Hayward A, Cookson BD, Cooper BS, Duckworth G, Jeanes A, Roberts J, Teare L, Stone S. (2012) The Feedback Intervention Trial (FIT) –improving hand-hygiene compliance in UK healthcare workers: a stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 7(10): e41617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Atkins L, West R. (2014) The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide To Designing. Sutton: Silverback Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardemann W, Eccles MP, Cane J, Wood CE. (2013) The Behavior Change Technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an International consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 46(1): 81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. (2011) The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science 6: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]