Abstract

Nutrition deals with ingestion of foods, digestion, absorption, transport of nutrients, intermediary metabolism, underlying anabolism and catabolism, and excretion of unabsorbed nutrients and metabolites. In addition, nutrition interacts with gene expressions, which are involved in the regulation of animal performances. Our laboratory is concerned with the improvement of animal productions, such as milks, meats and eggs, with molecular nutritional aspects. The present review shows overviews on the nutritional regulation of metabolism, physiological functions and gene expressions to improve animal production in chickens and dairy cows.

Keywords: chicken, dairy cow, gene expression, metabolism, nutrition

Introduction

Nutrition is the science of investigating interrelationships between the animal's body and its feed. Recent trends in increased accumulation of knowledge and technology in the nutrition, biochemistry and molecular biology of tissues, cells and genes of animal species, nutrition today has evolved toward an integrated science unifying many aspects related to biological science. I and collaborators have studied to develop the novel animal production system which provides high quality products with low cost using molecular nutritional techniques in chickens and cows. Based on these aspects, I introduce, in the present review, the four points of our results; that is, characterization of chicken lipoprotein metabolism, adipocyte and myoblast regulation with the improvement of meat production, improvement of immune function, and the reduction of oxidative stress.

Characterization of Chicken Lipoprotein Metabolism

Lipogenic activity in the liver is much greater than in adipose tissue in chickens and most fats accumulated in adipose tissues may be accounted for by incorporation of triacylglycerols from plasma lipoproteins which are either synthesized in the liver or provided from dietary fats (Griffin & Hemier 1988). On the other hand, fat synthesizing and accumulation are mainly regulated by adipose tissue in mammals, while in chickens, fat accumulation in adipose tissue is dependent on uptake of triacylglycerols from very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) secreted and transported from liver. In this process, lipoprotein lipase (LPL)‐catalyzed hydrolysis of triacylglycerols in adipose tissues is the rate‐limiting step. The crucial role of LPL has been evidenced by inhibition of LPL activity by anti‐LPL monoclonal antibody causing lipemia and decreasing adipose fat deposition to half that of control chickens (Sato et al. 1999a). Thus, LPL has been targeted for nutritional modification in order to reduce the fatness of chickens safely and in the consumer's perception. However, LPL messenger RMA (mRNA) expression in growing chickens is less responsive to aging and nutritional manipulation than in mammals (Sato & Akiba 2002), indicating species‐specificity in the regulatory mechanism in fat deposition as well as functionality of nutrients and/or feed ingredients. We have further explored two possibilities to modulate chicken fat deposition, which are the regulation of LPL‐catalyzed hydrolysis (Sato et al. 1999b) and VLDL secretion from liver (Tachibana et al. 2002; Chiba et al. 2003; Tachibana et al. 2005).

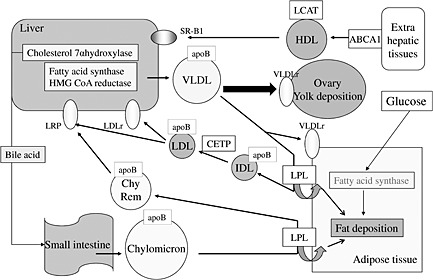

Lipoprotein metabolism in chickens has the species characterization described above. In addition, the developing oocytes of laying hens have been identified as a characteristic site for lipid deposition (Schneider et al. 1998). These results suggest a species‐specific difference between chicken and mammalian lipid metabolism. Based on these speculations, we have further investigated the characterization of lipid metabolism in chickens. Figure 1 shows the brief overview of chicken lipid metabolism described by our research. At first, we identified the molecular characterization of two key enzymes, 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase and cholesterol 7‐alpha hydroxylase, that are the regulators of cholesterol metabolism (Sato et al. 2003). Further studies on regulatory factors involved in lipoprotein and cholesterol metabolism also provided cholesteryl ester transfer protein (Sato et al. 2007), lipase gene family (Sato et al. 2010), lipoprotein remnant (Sato et al. 2009a) and angiopoietin‐like 3 (Sato et al. 2008). In addition, the transcriptional factors to regulate these factors were identified (Seol et al. 2007; Sato & Kamada 2011). The role of Liver X receptors (LXRs) on lipid metabolism was determined in chicken primary hepatocytes, with results showing that LXR activates not only fatty acid synthesis but also bile acid and cholesterol synthesis in these cells (Sato & Kamada 2011). Then, the novel methods reducing fat deposition in chickens might be developed by new techniques using molecular nutrition, including LXR regulation.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of lipoprotein metabolism in chickens. VLDL, very low density lipoprotein; IDL, intermediate density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; VLDLr, VLDL receptor; LDLr, LDL receptor; LRP, LDL receptor‐related protein; LCAT, lecithin‐cholesterol acyltransferase; ABCA1, ABC transporter 1; CETP, cholesteryl ester transfer protein; SR‐B1, schavenger receptor B1.

Adipocyte and Myoblast Regulation with the Improvement of Meat Production

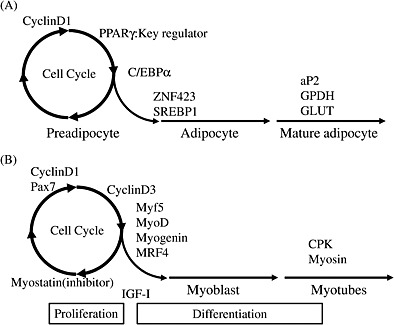

Obesity, a condition in which there is an excessive amount of adipose tissue mass in relation to lean body mass, is a nutritional disorder most prevalent in animals. The increase in adipose tissue mass can result from the multiplication of new fat cells through adipogenesis and/or from increased deposition of cytoplasmic triglycerides (Soukas et al. 2001). In studying the development of adipose tissue in chickens, it has previously been shown that increases in the abdominal fat pad mass of broiler chickens mainly depends on hyperplasia of adipocytes until 4 weeks of age and from thereafter on hypertrophic growth (Hood 1982). Peroxisome proliferation‐activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is key regulatory factor in fat deposition in the hypertrophic growth stage of chicken adipose tissues (Sato et al. 2004, 2009b) and in the early stages of chicken pre‐adipocyte differentiation (Matsubara et al. 2005). Differentiation from pre‐adipocyte to mature adipocyte results in cell growth arrest (Ntambi & Young‐Cheul 2000). Thus, one might expect that the activation of PPARγ in the hypoplasia stage of fat accumulation causes decreased fat deposition in chickens after growth, so as to induce adipocyte cell growth arrest. We clearly demonstrated that the abdominal adipose tissue weight in chickens given a single intraperitoneal injection of troglitazone, a PPARγ agonist, at 1 day of age was lower than that of control chickens (Sato et al. 2008). It is therefore likely that PPARγ plays an important role in the regulation of both the hyperplasia of adipocytes and hypertrophic growth in broiler chickens, and that the activation of PPARγ in the hyperplasia stage of chicken adipose tissue deposition effectively manipulates fatness in broiler chickens (Fig. 2A). In addition, the other regulatory factors of adipocyte differentiation, PPARβ/δ (Sato et al. 2009c), ZNF423, KLFs and FGF10 (Matsubara et al. 2013), were identified. These results may provide novel information for improvement of chicken meat production.

Figure 2.

Transcriptional factors involved in cell proliferation and differentiation in adipocyte (A) and myoblast (B).

Skeletal muscle fibers are formed during embryogenesis and continue to enlarge post‐natally until mature size has been reached. In chicks, myoblast proliferation, differentiation and fusing into myofibers continue during the early stage of post‐hatch growth until day 3 (Halevy et al. 2004). It is therefore likely that this period, that is a few days prior to hatching, may be targeted for the modulation of growth performance and meat weight in chickens. In order to explore novel methods to control chicken performance, it may be beneficial to accumulate knowledge of the expression of regulatory factors that are involved in myoblast differentiation during myogenesis in chickens (Fig. 2B). We reported that insulin and this signaling (insulin/PI3K/Akt) is involved in the process of myogenesis, such as proliferation and differentiation in vivo and in vitro, and insulin or tolbutamide administration in newly hatched chicks is an efficient manipulation to improve chicken performance after growth (Sato et al. 2012a). These results provided not only species difference of insulin action in chick myoblast but also novel basic information for improvement of chicken meat production.

Improvement of Immune Function

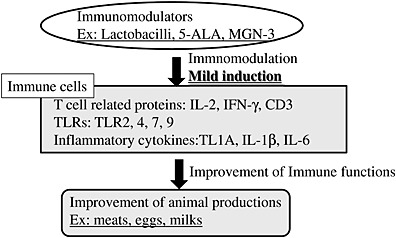

Meat production in the broiler industry needs to decrease or stop the use of antibiotics which are used to prevent disease and thereby promote growth in poultry (Ferket 2004). An alternative way to avoid the use of antibiotics is the control of the immune system that enhances humoral immunity and minimizes immunological stress in chickens (Klasing 1998). Immunomodulators could protect chickens from disease without decreasing growth performance by enhancing the immune system and could be used as a substitute for antibiotics. However, chicken immune systems have species‐specific differences compared to mammals. We reported that TL1A plays an important role as a pro‐inflammatory cytokine instead of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α in chickens (Takimoto et al. 2008). Then, it is important to identify new supplements which act as immunomodulators in chickens for efficient meat production without antibiotics. The immune response in broiler chickens has been evaluated by the expression of T‐cell‐related mRNAs (including cluster of differentiation 3 (CD3), interleukin (IL)‐2, interferon (IFN)‐γ) and toll‐like receptors (TLRs) in the foregut and spleen, as well as phagocytes of blood mononuclear cells (MNC), mitogen (concanavalin A (Con A))‐induced proliferation of splenic MNC of growing broiler chickens (Takahashi et al. 2008, 2010). Thus, we identified three molecules using these parameters (Fig. 3). The lactobacilli used in the study, particularly Lactobacillus gasseri TL2919, enhanced development of the gut immune system in neonatal chicks, suggesting that they could be useful as immunomodulators that minimize immunological stress and therefore protect chicks from disease without decreasing growth performance (Sato et al. 2009d). Modified arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN‐3), which is a denatured hemicellulose obtained by reacting rice bran hemicellulose with multiple carbohydrate hydrolyzing enzymes from the shiitake mushrooms, enhances the expression of T‐cell‐related mRNAs and TLRs in the foregut and spleen, as well as phagocytes of blood MNC and mitogen‐induced proliferation of splenic MNC of growing broiler chickens (Sato et al. 2012b). In addition, the inflammatory response resulting from Escherichia coli lipoploysaccharide‐induced immune stimulation was improved in the chickens fed 5‐aminoleevulinic acid (5‐ALA)‐supplemented diets, resulting in improvements in performance (Sato et al. 2012c). Further investigation on nutritional modification of immune developments and responses in broiler chicks may improve production efficiency under stressful raising conditions.

Figure 3.

Improvement of animal production by immunomodulators. CD3, cluster of differentiation 3; IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; TLR, toll‐like receptor; TL1A, tumor necrosis factor‐like ligand 1A, MGN‐3, modified arabinoxylan rice bran; 5‐ALA, 5‐aminoleevulinic acid.

The Reduction of Oxidative Stress in Dairy Cows

Oxidative stress leads to aging and disease in animals, and is caused by an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant activity. Although ROS play an important role in biological defense against infections, they also injure cells, DNA, RNA, proteins, carbohydrates and lipids, which can in turn give rise to serious health problems (Boots et al. 2008; Herrera et al. 2009). A serious problem for the dairy industry is the lipid oxidation of milk fats which gives rise to lipocatabolic odor (Lindmark‐Månsson & Akesson 2000). These odors result from unsaturated fatty acid oxidation by reactive oxygen during long‐term preservation (Al‐Mabruk et al. 2004). Based on this concept, it has been reported that the supplementation of antioxidative nutrients; that is, vitamin E (Al‐Mabruk et al. 2004; Sympoura et al. 2009), in the diets of dairy cows could result in milk with a low lipid peroxide content and high antioxidant activity. However, milk with a high antioxidant and low lipid peroxide content has not been developed, because ruminants have a specific digestive organ, that is the rumen.

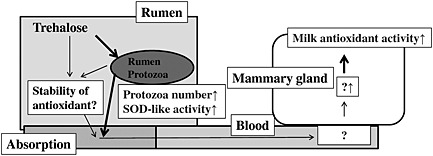

Trehalose is a natural disaccharide composed of two molecules of glucose joined by an α,α‐1,1 glucosidic linkage; it is used widely, particularly as a food additive and in cosmetics, as well as for its antioxidant activity (Oku et al. 2003). We reported that dietary supplementation with trehalose brings about an improvement of oxidative status in the rumen fluid, blood and milk of cows treated in this manner compared to controls (Aoki et al. 2010). These results suggest that trehalose is useful as a supplement for reducing oxidative stress in dairy cows and improving milk quality. In addition, the antioxidant activity associated with trehalose supplementation is not a direct antioxidative effect of trehalose, but due to improvements in ruminal antioxidative conditions, particularly with respect to an increase of relative superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity (Aoki et al. 2013). We suggested that the low lipid peroxide and high antioxidant content in the rumen fluid of cows fed trehalose‐supplemented diets might be explained by the enhancement of protozoal activities through the activation of rumen fermentation (Fig. 4). Further molecular nutritional approach, that is, a study to determine the relationship between relative SOD activity in rumen fluid and antioxidant activity in milk, as well as alterations to rumen microbes and mammary gland cells in cows fed trehalose‐supplemented diets, may help to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the effect of trehalose supplementation.

Figure 4.

Possible mechanism underlying the antioxidant activity associated with trehalose supplementation of the diet in dairy cows.

Conclusion

Recent advanced biochemistry and molecular biology has made it possible to provide information on the modification site in genomic DNA, transcriptome, proteome and metabolome against nutrition. The deposition of these data will enhance novel molecular nutritional regulation to improve animal production and animal health, resulting in the development of novel animal production systems.

Sato, K. (2016) Molecular nutrition: Interaction of nutrients, gene regulations and performances. Anim Sci J, 87: 857–862. doi: 10.1111/asj.12414.

References

- Al‐Mabruk RM, Beck NF, Dewhurst RJ. 2004. Effects of silage species and supplemental vitamin E on the oxidative stability of milk. Journal of Dairy Science 87, 406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki N, Furukawa S, Sato K, Kurokawa Y, Kanda S, Takahashi Y, et al 2010. Supplementation of the diet of dairy cows with trehalose results in milk with low lipid peroxide and high antioxidant content. Journal of Dairy Science 93, 4189–4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki N, Sato K, Kanda S, Mukai Y, Obara Y, Itabashi H. 2013. Time course of changes in antioxidant activity of milk from dairy cows fed a trehalose‐supplemented diet. Animal Science Journal 84, 42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boots AW, Haenen GR, Bast A. 2008. Health effects of quercetin: from antioxidant to nutraceutical. Europian Journal of Pharmacology 585, 325–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba T, Sato K, Tachibana S, Takahashi K, Nishida A, Akiba Y. 2003. Preparation of monoclonal antibody against chicken apolipoprotein B development of enzyme liked immunosolvent assay(ELISA) method with the antibody aiming at the optimization of lipid metabolism in Chickens. Journal of Poultry Science 40, 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ferket PP. 2004. Alternative to antibiotics in poultry production: response, practical, experience and recommendations In: Lyons TP, Jacques KA. (eds), Nutritional Biotechnology in the Feed and Food Industries, pp. 57–67. Nottingham University Press, Nottingham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin HD, Hemier D. 1988. Plasma lipoprotein metabolism and fattening on poultry In: Leclercq B, Whitehead CC. (eds), Leanness in Domestic birds, pp. 175–201. Butterworths, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Halevy O, Piestun Y, Allouh MZ, Rosser BW, Rinkevich Y, Reshef R, et al 2004. Pattern of Pax7 expression during myogenesis in the posthatch chicken establishes a model for satellite cell differentiation and renewal. Developmental Dynamics 231, 489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera E, Jiménez R, Aruoma OI, Hercberg S, Sánchez‐García I, Fraga C. 2009. Aspects of antioxidant foods and supplements in health and disease. Nutritional Review 67, S140–S144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood RL. 1982. The cellular basis for growth of the abdominal fat pad in broiler‐type chickens. Poultry Science 61, 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasing KC. 1998. Nutritional modulation of resistance to infectious diseases. Poultry Science 77, 1195–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindmark‐Månsson H, Akesson B. 2000. Antioxidative factors in milk. British Journal of Nutrition 84, S103–S110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara Y, Sato K, Ishii H, Akiba Y. 2005. Changes in mRNA expression of regulatory factors involved in adipocyte differentiation during fatty acid induced adipogenesis in chicken. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology‐Part A 141, 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara Y, Aoki M, Endo T, Sato K. 2013. Characterization of the expression profiles of adipogenesis‐related factors, ZNF423, KLFs and FGF10, during preadipocyte differentiation and abdominal adipose tissue development in chickens. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology‐Part A 165, 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntambi JM, Young‐Cheul K. 2000. Adipocyte differentiation and gene expression. Journal of Nutrition 130, 3122S–3126S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oku K, Watanabe H, Kubota M, Fukuda S, Kurimoto M, Tsujisaka Y, et al 2003. NMR and quantum chemical study on the OH…pi and CH…O interactions between trehalose and unsaturated fatty acids: implication for the mechanism of antioxidant function of trehalose. Journal of American Chemical Society 125, 12739–12748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Akiba Y. 2002. Lipoprotein lipase mRNA expressions in adipose tissues are little modified by aging nutritional state in broiler chickens. Poultry Science 81, 846–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Kamada T. 2011. Regulation of bile acid, cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in chicken primary hepatocytes by different concentrations of T0901317, an agonist of Liver X receptors. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology‐Part A 158, 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Akiba Y, Chida Y, Takahashi K. 1999a. Lipoprotein hydrolysis fat accumulation of Lipoprotein lipase monoclonal antibodies. Poultry Science 78, 1286–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Takahashi T, Takahashi Y, Shiono H, Katoh N, Akiba Y. 1999b. Preparation of chylomicrons and VLDL with monoacid‐rich triacylglycerol and characterization of kinetic parameters in lipoprotein lipase‐mediated hydrolysis in chickens. Journal of Nutrition 129, 126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Ohuchi A, Seol HS, Toyomizu M, Akiba Y. 2003. Changes in mRNA expression of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutary coenzyme A reductase cholesterol 7 alpha‐hydroxylase in chickens. Biochimia et Biophysica Acta 1630, 96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Fukao K, Seki Y, Akiba Y. 2004. Expression of the chicken peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma gene is influenced by aging, nutrition agonist administration. Poultry Science 83, 1342–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Ohuchi A, Sato T, Schneider WJ, Akiba Y. 2007. Molecular characterization and expression of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene in chickens. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology‐Part B 148, 117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Matsushita K, Matsubara Y, Kamada T, Akiba Y. 2008. Adipose tissue fat accumulation is reduced by a single intraperitoneal injection of PPARgamma agonist when given to newly hatched chicks. Poultry Science 87, 2281–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Suzuki K, Akiba Y. 2009a. Characterization of chicken portomicron remnant and very low density lipoprotein remnant. Journal of Poultry Science 46, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Abe H, Kono T, Yamazaki M, Nakashima K, Kamada T, Akiba Y. 2009b. Changes in peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma gene expression of chicken abdominal adipose tissue with different age, sex and genotype. Animal Science Journal 80, 322–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Yonemura T, Ishii H, Toyomizu M, Kamada T, Akiba Y. 2009c. Role of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor beta/delta in chicken adipogenesis. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology‐Part A 154, 370–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Takahashi K, Tohno M, Miura Y, Kamada T, Ikegami S, Kitazawa H. 2009d. Immunomodulation in gut‐associated lymphoid tissue of neonatal chicks by immunobiotic diets. Poultry Science 88, 2532–2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Seol HS, Kamada T. 2010. Tissue distribution of lipase genes related to triglyceride metabolism in laying hens (Gallus gallus). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology‐Part B 155, 62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Aoki M, Kondo R, Matsushita K, Akiba Y, Kamada T. 2012a. Administration of insulin to newly hatched chicks improves growth performance via impairment of MyoD gene expression and enhancement of cell proliferation in chicken myoblasts. General and Comparative Endocrinology 175, 457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Takahashi K, Aoki M, Kamada T, Yagyu S. 2012b. Dietary supplementation with modified arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN‐3) modulates inflammatory responses in broiler chickens. Journal of Poultry Science 49, 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Matsushita K, Takahashi K, Aoki M, Fujiwara J, Miyanari S, Kamada T. 2012c. Dietary supplementation with 5‐aminolevulinic acid modulates growth performance and inflammatory responses in broiler chickens. Poultry Science 91, 1582–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider WJ, Osanger A, Waclawek M, Nimpf J. 1998. Oocyte growth in the chicken: receptors and more. Biological Chemistry 379, 965–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol HS, Sato K, Matsubara Y, Schneider WJ, Akiba Y. 2007. Modulation of sterol regulatory element binding protein‐2 in response to rapid follicle development in chickens. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology‐Part B 147, 698–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukas A, Socci ND, Saatkamp BD, Novelli S, Friedman JM. 2001. Distinct transcriptional profiles of adipogenesis in vivo and in vitro. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276, 34167–34174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sympoura F, Cornu A, Tournayre P, Massouras T, Berdagué JL, Martin B. 2009. Odor compounds in cheese made from the milk of cows supplemented with extruded linseed and alpha‐tocopherol. Journal of Dairy Science 92, 3040–3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana S, Sato K, Takahashi T, Akiba Y. 2002. Octanoate inhibits very low‐density lipoprotein secretion in primary culture of chicken hepatocytes. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology‐Part A 132, 621–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana S, Sato K, Cho Y, Chiba T, Schneider WJ, Akiba Y. 2005. Octanoate reduces very low‐density lipoprotein secretion by decreasing the synthesis of apolipoprotein B in primary cultures of chicken hepatocytes. Biochimia et Biophysica Acta 1737, 36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Aoki A, Takimoto T, Akiba Y. 2008. Dietary supplementation of glycine modulates inflammatory response indicators in broiler chickens. British Journal of Nutrition 100, 1019–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Kitano A, Akiba Y. 2010. Effect of L‐carnitine on proliferative response and mRNA expression of some of its associated factors in splenic mononuclear cells of male broiler chicks. Animal Science Journal 81, 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto T, Sato K, Akiba Y, Takahashi K. 2008. Role of chicken TL1A on inflammatory responses and partial characterization of its receptor. Journal of Immunology 180, 8327–8332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]