ABSTRACT

Background

In thyroid surgery, preserving the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) is crucial for preventing postoperative phonatory dysfunction. Right nonrecurrent laryngeal nerves (NRLNs) are not particularly rare, and they are vulnerable to injury during surgery. This anomaly is associated with a right aberrant subclavian artery. Thus, a right‐sided aortic arch with an aberrant left subclavian artery (LSA) suggests a possible left NRLN.

Methods

We report the cases of 4 patients with right‐sided aortic arch and aberrant LSA. Preoperative imaging studies revealed those anomalies, but no signs of situs inversus. During the surgeries, only 1 of the 4 cases had a left NRLN. We retrospectively evaluated the patients' imaging studies.

Results

An aortic diverticulum was found at the point at which the aberrant LSA originated in the 3 patients with left‐RLNs, but not in the patient with the left‐NRLN.

Conclusion

In right‐sided aortic arch + aberrant LSA cases, the absence of an aortic diverticulum suggests a left NRLN. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Head Neck 38: First–E2511, 2016

Keywords: left nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve, right aortic arch, aberrant left subclavian artery, chromosome 22q11 deletion, intraoperative neural monitoring

INTRODUCTION

In thyroid surgery, the identification and preservation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) are crucial for preventing postoperative phonatory dysfunction. In ordinary cases, after branching off from the vagus nerve, the RLN loops around the right subclavian artery (RSA) on the right side and goes around the aortic arch on the left side. Right nonrecurrent inferior laryngeal nerves (NRLNs) have been reported as an anatomic variant, associated with a congenital anomaly of great vessels. There are several reports contending that the right NRLN is associated with an aberrant RSA.1 Thus, a right‐sided aortic arch with an aberrant left subclavian artery (LSA) suggests a possible left NRLN. However, in the present series of 4 patients who had a right‐sided aortic arch and an aberrant LSA, only 1 of the 4 cases had a left NRLN. In this report, we attempted to clarify the etiology of left NRLN by examining these 4 cases.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

The patient was a 21‐year‐old Japanese man. In his early childhood, he was diagnosed as having chromosome 22q11 deletion, and he had a history of congenital hypoparathyroidism and thymus hypoplasia. He also had a ventricular septum defect and an atrial septum defect, which had been surveyed without operation. His medical history included surgeries for an umbilical hernia and an abdominal hernia, but he had never undergone a cardiovascular surgery. He was referred to our hospital for the evaluation of a thyroid tumor.

An ultrasound examination revealed a tumor 36 mm in diameter in the left lobe, with many microcalcifications, heterogeneous density, and an obscure border line. A fine‐needle biopsy of the tumor was performed, and the diagnosis was a suspected adenomatous nodule. A chest X‐ray showed a right‐sided aortic arch, but no indication of situs inversus was observed. A chest CT scan at the referring hospital showed a right‐sided aortic arch and an aberrant LSA running behind the main trachea and the thoracic esophagus, and crossing the midline of the mediastinum. This aberrant LSA originated from the descending aorta as the fourth branch of the aortic arch, after the left common carotid artery, the right common carotid artery, and the RSA arose in this sequence.

We also confirmed the anomalies with magnetic resonance angiography (see Figure 1). Thus, we suspected that left NRLN might be present. A preoperative laryngoscopic examination showed normal vocal cord function. The patient had no symptoms of dysphagia or regurgitation. Although a fine‐needle biopsy of the tumor indicated that the tumor was benign, we decided to perform surgery because the ultrasound examination indicated the possibility of malignancy.

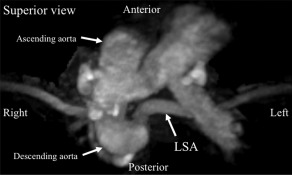

Figure 1.

Case 1, a 21‐year‐old Japanese man. The superior view of the 3D magnetic resonance angiograph revealed the aortic arch anomalies. An aberrant left subclavian artery (LSA) originated from the descending aorta as the fourth branch of the aortic arch.

A left hemithyroidectomy was performed. For the surgery, the patient was administered general anesthesia with an endotracheal tube with surface electrodes. We used the NIM‐Response 3.0 system (Medtronic, Jacksonville, FL) to confirm the RLN and the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. During the surgery, we detected a nerve running down along the lateral edge of the thyroid cartilage from the vagus nerve at the level of the upper border of the thyroid cartilage to the laryngeal entry point adjunct to Berry's ligament (see Figure 2).

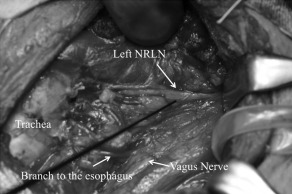

Figure 2.

A left nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve (NRLN) was running along the lateral edge of the thyroid cartilage from the vagus nerve at the level of the upper border of the thyroid cartilage to the laryngeal entry point adjunct to Berry's ligament.

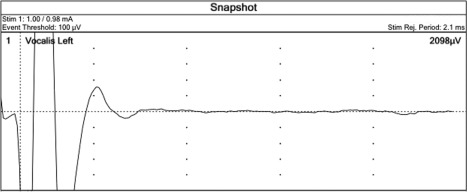

We then stimulated the nerve with the electrode and observed the electrically evoked electromyography signals. The electromyography results showed a clear and strong response with amplitude of 2098 μV and shorter latency compared with the following stimulation of the left vagus nerve in ordinary cases, which indicated that the nerve was a left NRLN (see Figure 3). The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve on the surface of the inferior constrictor muscle, running superficially in parallel with the NRLN, was also confirmed with the electromyography.

Figure 3.

A left nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve was confirmed with electromyography after the electrical stimulation.

After the surgery, the laryngoscopic examination showed normal vocal cord function, and the patient did not notice any significant changes in his voice. A histological examination revealed the widely invasive type of follicular carcinoma of the thyroid. Patients with the widely invasive type of follicular carcinoma are commonly followed up at our institute by a completion total thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine therapy. In this case, however, the patient had been receiving only thyroid‐stimulating hormone suppression therapy because he had congenital mild hypoparathyroidism because of his chromosome 22q11 deletion, and, thus, it would be impossible to avoid severe permanent hypoparathyroidism after a completion total thyroidectomy. The postoperative course was uneventful, and no recurrence of the malignancy has been observed as of this writing 15 months after the surgery.

Cases 2, 3, and 4

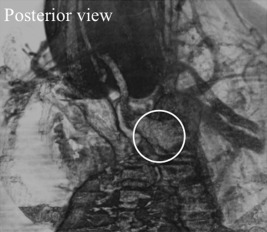

Before treating case 1, we had treated 3 other Japanese patients with a right‐sided aortic arch and an aberrant LSA, all of whom underwent a thyroidectomy at our hospital. They were a 55‐year‐old man, a 55‐year‐old woman, and a 28‐year‐old woman at the time of their surgeries (Table 1). Before the surgeries, we detected these anomalies in all 3 cases by CT scans, and we suspected that a left NRLN might be present. However, during the surgeries, we found normal left RLNs in all 3 cases. After the surgical detection of left NRLN in case 1, we reevaluated the images of that patient and the other 3 cases with normal RLNs, and we found that a diverticulum of the descending aorta at the point at which the aberrant LSA originated (see Figure 4) could be observed in the 3 patients with the left RLN and not in the patient with a left NRLN. In all of the patients with the left RLNs, the descending aorta kinked toward the medial side in close proximity to the aortic arch, ballooned as a diverticulum at the point at which the aberrant LSA originated, and turned to the right side, running down caudally. In contrast, in case 1 with the left NRLN, the descending aorta went straight down after the aortic arch.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients with a right‐sided aortic arch with an aberrant left subclavian artery.

| Age, y | Sex | Diagnosis | Operative procedure | Left NRLN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 21 | Male | Follicular cancer | Hemi‐thyroidectomy | (+) |

| Case 2 | 55 | Male | Adenomatous nodule | Hemi‐thyroidectomy | (−) |

| Case 3 | 55 | Female | Papillary cancer | Total thyroidectomy | (−) |

| Case 4 | 25 | Female | Grave disease | Total thyroidectomy | (−) |

Abbreviation: NRLN, nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve.

Figure 4.

The posterior view of the 3D CT shows a diverticulum of the descending aorta (in the circle) at the point at which the left subclavian artery originates could be detected in the patients with a left recurrent laryngeal nerve.

DISCUSSION

A right NRLN is not a very rare anatomic variant, with an incidence of 0.3% to 0.8%.2, 3 However, a left NRLN is extremely rare. Right NRLNs are associated with a right aberrant subclavian artery. Thus, one might suspect a left NRLN in patients with a right‐sided aortic arch and an aberrant LSA.

If the RSA originates anomalously as the fourth branch of the aortic arch because of the anomalous regression of the distal right dorsal aorta, the right inferior laryngeal nerve will become an NRLN. If the same anomaly occurs in a patient with situs inversus, the left inferior laryngeal nerve will become an NRLN. Thus far, there have been few reports describing a left NRLN, and most of these were associated with situs inversus. In 2008, Fellmer et al4 reported the first case of a left NRLN that was not associated with situs inversus. In that patient, truncus arteriosus communis was coexisting, which might be one of the reasons for the disappearance of left ductal arteriosus (DA) during the embryonic development. Fellmer et al4 also reported that, in the absence of situs inversus, the following 3 developmental abnormalities were necessary for left NRLN: (1) the presence of a right‐sided aortic arch; (2) an aberrant LSA; and (3) the absence of a DA. In the present case, we suspected a potential left NRLN based on the preoperative imaging studies and later confirmed its presence and its association with an aberrant LSA. Moreover, we confirmed a left NRLN with intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring for the first time.

To understand the basis of the NRLN, we should consider the embryonic development of the inferior laryngeal nerve and the aortic arch. In the embryo, the inferior laryngeal nerves supply their respective sixth branchial arches. When the heart descends, the inferior laryngeal nerves loop around all 6 aortic arches on the respective sides. If all 6 arches disappeared on 1 side, an NRLN on the respective side would appear. On the right side in the normal anatomy, the RLN loops only the fourth aortic arch as the RSA. Therefore, if the RSA originates anomalously as the fourth branch of the aortic arch because of the anomalous regression of the distal right dorsal aorta, the inferior laryngeal nerve will stay in the neck and become a right NRLN. On the left side, the RLN loops both the fourth aortic arch as the adult aortic arch and the sixth aortic arch as the DA. Therefore, regression of both the fourth and the sixth aortic arches is a crucial point in the development of a left NRLN.

A right‐sided aortic arch, the persistence of the right fourth aortic arch, is a relatively rare vascular anomaly, with a reported incidence of approximately 0.1%.5 In the same report, cases with an aberrant LSA originating from the descending aorta were found to account for 40% of cases with right‐sided aortic arch.5 Taking these facts into account, the incidence rate of left NRLN is much less than that of a right‐sided aortic arch with an aberrant LSA.

In fact, it has been reported that normal left RLNs were identified upon surgical treatment of each of 6 patients with lung cancer with a right‐sided aortic arch and an aberrant LSA.6 Consequently, a crucial point in the identification of a left NRLN is to determine whether or not the left sixth aortic arch functioning as the left DA has regressed in embryotic development. To comprehend anomalies of the derivatives of the aortic arch system, Edwards7 suggested that malformations of the aortic arch derivatives might be divided into 2 groups, depending on whether the DA took its origin from the left pulmonary artery or from the right pulmonary artery.

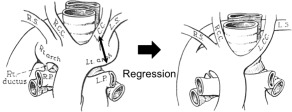

According to Edwards'7 classification, a right‐sided aortic arch with an LSA that originates from the descending aorta as the fourth branch of the aortic arch follows 1 of 2 patterns. In the first, the DA originates from the left pulmonary artery and exhibits partial regression of the left portion of the double aortic arch between the origins of the left common carotid artery and the LSA. The LSA arises as the fourth branch of the aorta from a diverticulum to which the DA is also attached (see Figure 5). In this pattern, there is a vascular ring about the trachea and the esophagus. However, a left NRLN cannot appear as in the present cases 2 to 4, because the RLN loops the left DA in these cases.

Figure 5.

According to Edwards' 7 classification, a right‐sided aortic arch with a left subclavian artery (LSA) originating from the descending aorta as the fourth branch of the aortic arch takes 2 patterns. This figure shows an example of the first pattern, which has the ductus arteriosus originating from the left pulmonary artery and shows partial regression of the left portion of the double aortic arch between the origins of the left common carotid (LCA) artery and the LSA. RS, right subclavian artery; RCC, right common carotid artery; LCC, left common carotid artery; LS, left subclavian artery; LP, left pulmonary artery; RP, right pulmonary artery. Source: Edwards JE. Med Clin North Am 1948;32:925–949.

The second pattern in Edwards'7 classification has the DA originating from the right pulmonary artery with partial regression of the left portion of the double aortic arch between the origins of the left common carotid artery and the LSA (see Figure 6). The results for this second pattern are a mirror image of the vascular anomaly appearing in a right NRLN. In this pattern, the left inferior laryngeal nerve loops no aortic arches and becomes a left NRLN as in the present case 1.

Figure 6.

An example of the second pattern, in which the ductus arteriosus originates from the right pulmonary artery, and there is partial regression of the left portion of the double aortic arch between the origins of the left common carotid (LCA) and the left subclavian artery (LSA), according to Edwards' 7 classification. RS, right subclavian artery; RCC, right common carotid artery; LCC, left common carotid artery; LS, left subclavian artery; LP, left pulmonary artery; RP, right pulmonary artery. Source: Edwards, JE. Med Clin North Am 1948;32:925–949.

As mentioned above, in the case of a right‐sided aortic arch with an aberrant LSA, development of a left NRLN depends on whether the DA originates from the left or right pulmonary artery. However, as we observed in the present cases, determining the position of the DA without a surgical procedure is very difficult because the DA is too narrow to detect by image‐based examinations. Instead, in cases with the first pattern, a so‐called Kommerell diverticulum can be found at the point at which the LSA originates from the descending aorta.8 On the other hand, in our case 1 with a left NRLN, there was no aortic diverticulum around that point. The differentiation of a left NRLN is thus aided by determining whether or not there is an aortic diverticulum around the point at which the LSA originates. The incidence of right DAs without situs inversus is unknown because of their extreme rarity.

The DA is also sometimes absent in left NRLNs. Although an early degeneration of the DA in embryonic development is fatal, the DA is often absent in cases of congenital cardiovascular malformations, such as truncus arteriosus communis9 and tetralogy of Fallot associated with chromosome 22q11 deletion.10 In the present case 1, because a ventricular septal defect and an atrial septal defect were identified, the right DA may have existed or may have been absent.

In conclusion, we have reported the first case of an intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring‐identified left NRLN that was associated with an aberrant LSA, and not with situs inversus. In right‐sided aortic arch + aberrant LSA cases, the absence of an aortic diverticulum suggests a left NRLN.

REFERENCES

- 1. Stedman GW. A singular distribution of some of the nerves and arteries of the neck and the top of the thorax. Edin Med Surg J 1823;19:564–565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henry JF, Audiffret J, Denizot A, Plan M. The nonrecurrent inferior laryngeal nerve: review of 33 cases, including two on the left side. Surgery 1988;104:977–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanders G, Uyeda RY, Karlan MS. Nonrecurrent inferior laryngeal nerves and their association with a recurrent branch. Am J Surg 1983;146:501–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fellmer PT, Böhner H, Wolf A, Röher HD, Goretzki PE. A left nonrecurrent inferior laryngeal nerve in a patient with right‐sided aorta, truncus arteriosus communis, and an aberrant left innominate artery. Thyroid 2008;18:647–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stewart JR, Kincaid OW, Titus JL. Right aortic arch: plain film diagnosis and significance. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1966;97:377–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wada H, Hida Y, Kaga K, et al. Video‐assisted thoracoscopic left lower lobectomy in a patient with lung cancer and a right aortic arch. J Cardiothoracic Surg 2012;7:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Edwards, JE . Anomalies of the derivatives of the aortic arch system. Med Clin North Am 1948;32:925–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kouchoukos NT, Masetti P. Aberrant subclavian artery and Kommerell aneurysm: surgical treatment with a standard approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:888–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Praagh R, Van Praagh S. The anatomy of common aorticopulmonary trunk (truncus arteriosus communis) and its embryologic implications. A study of 57 necropsy cases. Am J Cardiol 1965;16:406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johnson MC, Strauss AW, Dowton SB, et al. Deletion within chromosome 22 is common in patients with absent pulmonary valve syndrome. Am J Cardiol 1995;76:66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]