Abstract

This post hoc analysis of a phase 3 trial explored the effect of pixantrone in patients (50 pixantrone, 47 comparator) with relapsed or refractory aggressive B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) confirmed by centralized histological review. Patients received 28‐d cycles of 85 mg/m2 pixantrone dimaleate (equivalent to 50 mg/m2 in the approved formulation) on days 1, 8 and 15, or comparator. The population was subdivided according to previous rituximab use and whether they received the study treatment as 3rd or 4th line. Median number of cycles was 4 (range, 2–6) with pixantrone and 3 (2–6) with comparator. In 3rd or 4th line, pixantrone was associated with higher complete response (CR) (23·1% vs. 5·1% comparator, P = 0·047) and overall response rate (ORR, 43·6% vs. 12·8%, P = 0·005). In 3rd or 4th line with previous rituximab (20 pixantrone, 18 comparator), pixantrone produced better ORR (45·0% vs. 11·1%, P = 0·033), CR (30·0% vs. 5·6%, P = 0·093) and progression‐free survival (median 5·4 vs. 2·8 months, hazard ratio 0·52, 95% confidence interval 0·26–1·04) than the comparator. Similar results were found in patients without previous rituximab. There were no unexpected safety issues. Pixantrone monotherapy is more effective than comparator in relapsed or refractory aggressive B‐cell NHL in the 3rd or 4th line setting, independently of previous rituximab.

Keywords: pixantrone, salvage therapy, B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma, rituximab, post hoc study

Pixantrone is conditionally approved in Europe for the management of multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), on the basis of results from an open‐label, randomized phase 3 study comparing pixantrone with physician's choice of treatment in 140 patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive NHL (Pettengell et al, 2012). Treatment of heavily pre‐treated patients with pixantrone was reported to be efficacious and tolerable. The rate of complete response (CR) or unconfirmed complete response (CRu) with pixantrone was 20·0% [95% confidence interval (CI), 11·4–31·3%] vs. 5·7% (95% CI 1·6–14·0%) with comparator (P = 0·021). Treatment with pixantrone was also associated with a longer progression‐free survival (PFS) than comparator (5·3 vs. 2·6 months, P = 0·005). The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events with pixantrone were uncomplicated neutropenia, leucopenia and thrombocytopenia, all of which were manageable and in line with what would be expected for administration of a cytotoxic agent to heavily pre‐treated patients.

There are currently a number of first‐line treatment options in patients with aggressive B‐cell NHL, including anthracycline‐based regimens, with or without rituximab. Overall response rates (ORR) can reach 75% (Coiffier et al, 2010). However, there is less consensus on salvage regimens for the 25–35% of patients who fail to respond or relapse after first‐line therapy with standard protocols. Options include platinum‐containing regimens and autologous stem cell transplantation, though prognosis remains relatively poor (Chao, 2013). Pixantrone is currently the only salvage therapy with regulatory approval for patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive B‐cell NHL (Boyle & Morschhauser, 2015). The approval is conditional and confirmatory trials on pixantrone are underway. In the meantime, it is important to use all available data to further explore efficacy and safety in the patients for which it is approved.

This report describes a post hoc analysis of the phase 3 study described above (Pettengell et al, 2012) with the aim of investigating the effect of pixantrone in a subpopulation of patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive B‐cell NHL, as confirmed by centralized independent pathological review. We also explored the effect of pixantrone or comparator in this population divided according to whether they were receiving the study treatment as their 3rd or 4th line of therapy or as any line of therapy (i.e. all patients, including those receiving therapy as 3rd or 4th line and above), as well as whether they had previously received rituximab treatment or not.

Patients and methods

Main study design and treatment

The design and methods of this phase 3 study have been described (Pettengell et al, 2012). Briefly, this multicentre, open‐label, randomized trial included patients with aggressive de novo or transformed NHL [according to the Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) and World Health Organization (WHO) classifications], who had relapsed or were refractory to two or more previous lines of chemotherapy regimens, including at least one standard anthracycline‐based regimen with response ≥24 weeks. The protocol was amended during the study to exclude patients with no previous treatment with rituximab in countries where it was commercially available. Eligible patients had European Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0–2, measurable disease, no persisting toxicities from previous lines of treatment and adequate bone marrow and organ function. Patients who had received more than 450 mg/m2 doxorubicin or equivalent were excluded from the study, as were patients with clinically significant cardiovascular abnormalities with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 50% and New York Heart Association grade 3 or 4 heart failure.

The trial was performed in 66 hospital centres in Europe, India, Russia, South America, the UK and the USA between October 2004 and March 2008. All patients provided written informed consent and local ethical approval was obtained in all centres. The study was registered (www.ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00088530).

Patients were randomly allocated pixantrone or comparator. The patients in the pixantrone group received 28‐d cycles of 85 mg/m2 pixantrone dimaleate (equivalent to 50 mg/m2 in the base formulation approved by the European regulatory authorities) by intravenous infusion over 1 h on days 1, 8 and 15. The choice of comparator was left to the treating physician and could be vinorelbine, oxaliplatin, ifosfamide, etoposide, mitoxantrone or gemcitabine, all of which were given at prespecified standard doses and schedules (Pettengell et al, 2012). Randomization was achieved by an interactive voice response system and was stratified by region (USA versus Western Europe versus the rest of the World), International Prognostic Index (≤1 vs. ≥2) and previous stem cell transplantation. Patients were followed for 18 months after last treatment intake for disease progression and survival.

Post hoc study design

Our post hoc analysis included only patients with confirmation of histology by blinded centralized review of the lymph node biopsy or a tissue sample. In the main study protocol, histology was performed by an onsite pathologist and, in view of the urgent need for therapy, patients could be included in the main trial on the basis of this local evaluation (Pettengell et al, 2012). A second pathological evaluation was performed centrally and diagnosis involved consensus of two (or three in case of disagreement) independent pathologists. Diagnosis was identified as diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL), grade III follicular lymphoma, or transformed indolent lymphoma (i.e. confirmation that current disease was high‐grade DLBCL or grade III follicular lymphoma ‐like in patients with a history of indolent disease).

In our post hoc analysis, we explored outcomes in all patients with histological confirmation of aggressive B‐cell NHL by centralized review. We also further subdivided this population to explore outcomes in the subgroup of patients receiving study treatment as a 3rd or 4th line (i.e. excluding patients receiving it as 5th line or higher) and patients receiving it as any line of therapy and those with or without prior treatment with rituximab.

The primary outcome was the efficacy of pixantrone versus a selection of single agents in terms of proportion of patients who achieved CR or CRu in the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) population at end of treatment. Tumour response was assessed by an independent panel of three experts (a radiologist, an oncologist and a pathologist), who were blinded to both treatment assignment and the evaluation of response by the onsite pathologist. Response criteria were based on the 1999 International Working Group criteria (Cheson et al, 1999, 2007; Pettengell et al, 2012). Secondary outcomes included the proportion of people who achieved an overall response (CR, CRu, partial response and ORR), and length of PFS and overall survival (OS). All adverse events were recorded.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were used for baseline characteristics, adverse events and response rates. Values are presented as medians (range) or numbers (percentages). The difference between pixantrone and comparator in terms of CR and ORR was evaluated using a Fisher's exact test and the corresponding P values are presented. The level of statistical significance was set at 5%. Survival (PFS and OS) was analysed using the method of Kaplan and Meier and an unstratified log‐rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate the differences in PFS and OS between pixantrone and comparator, which are presented as a hazard ratio (HR) with the corresponding 95% CI. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.2 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

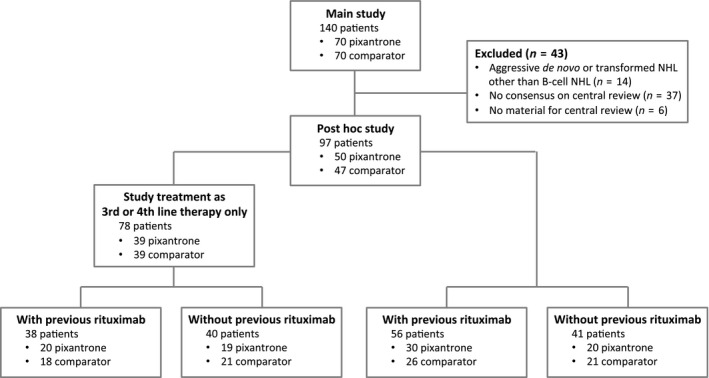

A total of 140 patients (pixantrone/comparator; n = 70/70) were included in the main study, of whom 126 had aggressive B‐cell NHL as determined by on‐site histology (Fig 1). Of these 126 patients, 99 patients (pixantrone/comparator, n = 50/49) were receiving study treatment as their 3rd or 4th line of treatment.

Figure 1.

Trial profile. NHL, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma.

A total of 97 of the 140 patients (69·2% of the original study population) had aggressive B‐cell NHL according to centralized review (50 patients treated with pixantrone, 47 patients treated with comparator). The rate of concordance of onsite review with centralized review was 76%. The reasons for exclusion from our post hoc analysis were lack of consensus on aggressive disease (20 patients treated with pixantrone, 17 patients treated with comparator) or no material for centralized review (3 patients treated with pixantrone, 3 patients treated with comparator).

The baseline characteristics of the 97 histologically confirmed patients are presented in Table 1. The median age of the population was 60·0 years (range 28–80 years) in the pixantrone group and 58 years (26–77 years) in the comparator group. There were fewer women in the pixantrone group (38% vs. 49%, respectively). Most of the patients had DLBCL (82 patients, 85%), with lesser proportions of transformed indolent lymphoma (12 patients, 12%) and grade III follicular lymphoma (3 patients, 3%). Three quarters of the population had an International Prognostic Index ≥2 (72 patients, 74%) and/or Ann Arbor stage III or IV (72 patients, 74%). About half the population had one or more extranodal sites (46 patients, 47%). Fifty‐six patients (58%) had previously received rituximab (30 pixantrone, 26 comparator) (Fig 1). More than three quarters of the population (78 patients, 80%) had previously received two or three lines of therapy (39 pixantrone, 39 comparator), of whom 38 patients (20 pixantrone, 18 comparator) had previously received rituximab (Fig 1). There were no relevant differences between the post hoc population and the population of the main study (Pettengell et al, 2012) in terms of demographic characteristics, diagnosis, or previous chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in 97 patients with aggressive B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma, according to centralized pathological review

| Patients with aggressive B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (N = 97) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pixantrone (n = 50) | Comparator (n = 47) | |

| Age, years | 60·0 (28–80) | 58·0 (26–77) |

| Female | 19 (38·0%) | 23 (48·9%) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma | 41 (82·0%) | 41 (87·2%) |

| Transformed indolent lymphoma | 7 (14·0%) | 5 (10·6%) |

| Grade III follicular lymphoma | 2 (4·0%) | 1 (2·1%) |

| International Prognostic Index | ||

| Score 0–1 | 12 (24·0%) | 13 (27·7%) |

| Score ≥2 | 38 (76·0%) | 34 (72·3%) |

| Ann Arbor stage | ||

| Stage I or II | 13 (26·0%) | 12 (25·5%) |

| Stage III or IV | 37 (74·0%) | 35 (74·5%) |

| ≥1 extranodal site | 24 (48·0%) | 22 (46·8%) |

| Previous chemotherapy | ||

| Number of lines | 3·0 (2–9) | 3·0 (2–8) |

| Two or three lines only | 39 (78·0%) | 39 (83·0%) |

| Previous rituximab | 30 (60·0%) | 26 (55·3%) |

Values are medians (range) or numbers and percentages.

The median number of drug cycles received during the study was four (range, two to six) in the pixantrone group and three (range, two to six) in the comparator group. More patients began a sixth cycle of study treatment in the pixantrone group [22 of 68 (32·4%)] than in the comparator group [19 of 67 (28·4%)].

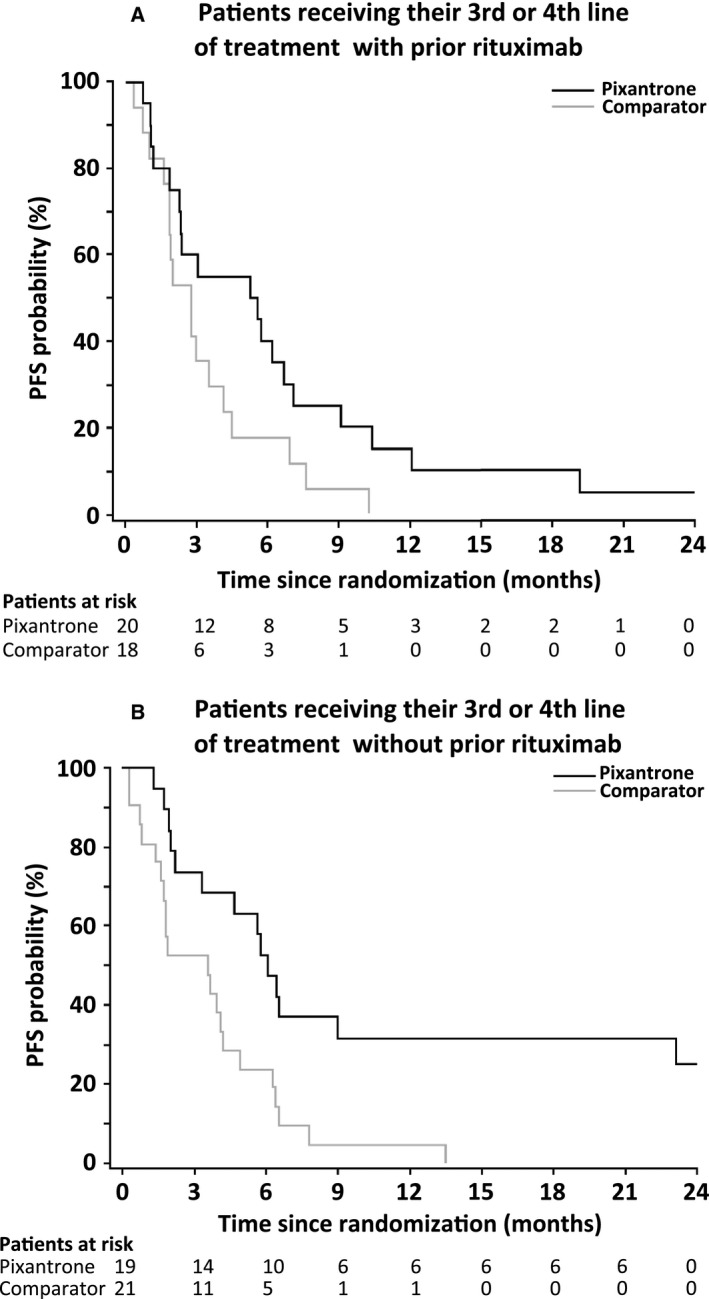

Treatment with pixantrone was associated with a trend to higher response rates than comparator in patients with histologically confirmed aggressive B‐cell NHL (Tables 2 and 3). When it was administered as 3rd or 4th line therapy in patients with histologically confirmed disease by central review, the rate of CR or CRu was 23·1% with pixantrone vs. 5·1% with comparator (P = 0·047) and ORR was 43·6% with pixantrone vs. 12·8% with comparator (P = 0·005) (Table 2). In the 38 patients who had previously received rituximab who were receiving the study treatment as a 3rd or 4th line therapy, there was also a significantly better ORR with pixantrone than comparator (45% vs. 11·1%, P = 0·033) and a trend for a better rate of CR or CRu (30·0% vs. 5·6%, P = 0·093) (Table 3). The PFS with pixantrone in these patients was 5·4 vs. 2·8 months for comparator (HR 0·52, 95% CI 0·26–1·04) (Fig 2A).

Table 2.

Response rates (CR, CR or CRu, ORR) until the end of study in patients with aggressive B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma receiving their 3rd or 4th line of therapy

| Pixantrone | Comparator | P‐valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with aggressive B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma determined by on‐site histology (n = 99) | |||

| Number of patients | 50 | 49 | |

| CR, n (%) | 9 (18·0%) | 0 (0·0%) | 0·003 |

| CR or CRu, n (%) | 14 (28·0%) | 2 (4·1%) | 0·002 |

| ORR, n (%) | 24 (48·0%) | 6 (12·2%) | <0·001 |

| Patients with aggressive B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma with histology determined by central review (n = 78) | |||

| Number of patients | 39 | 39 | |

| CR, n (%) | 7 (17·9%) | 0 (0·0%) | 0·012 |

| CR or CRu, n (%) | 9 (23·1%) | 2 (5·1%) | 0·047 |

| ORR, n (%) | 17 (43·6%) | 5 (12·8%) | 0·005 |

CR, complete response; CRu, unconfirmed complete response; ORR, overall response rate.

P value versus comparator (Fisher exact test).

Table 3.

Outcomes in patients with aggressive B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (determined by central review) and in patients receiving study treatment as 3rd or 4th line

| Patients with aggressive B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (N = 97) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With previous rituximab | Without previous rituximab | |||||

| Pixantrone | Comparator | P valuea | Pixantrone | Comparator | P valuea | |

| All patients (n = 97) | ||||||

| Number of patients | 30 | 26 | 20 | 21 | ||

| CR or CRu rate, n (%) | 6 (20·0%) | 3 (11·5%) | 0·481 | 3 (15·0%) | 1 (4·8%) | 0·343 |

| ORR, n (%) | 9 (30·0%) | 5 (19·2%) | 0·537 | 9 (45·0%) | 3 (14·3%) | 0·043 |

| Median PFS, months | 3·5 | 2·3 | 6·3 | 3·5 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 0·66 (0·38–1·14) | 0·35 (0·17–0·70) | ||||

| Median OS, months | 6·0 | 4·6 | 16·1 | 7·8 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 0·85 (0·48–1·50) | 0·52 (0·24–1·11) | ||||

| Patients receiving study treatment as 3rd or 4th line (n = 78) | ||||||

| Number of patients | 20 | 18 | 19 | 21 | ||

| CR or CRu rate, n (%) | 6 (30·0%) | 1 (5·6%) | 0·093 | 3 (15·8%) | 1 (4·8%) | 0·331 |

| ORR, n (%) | 9 (45·0%) | 2 (11·1%) | 0·033 | 8 (42·1%) | 3 (14·3%) | 0·078 |

| Median PFS, months | 5·4 | 2·8 | 6·1 | 3·5 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 0·52 (0·26–1·04) | 0·36 (0·18–0·73) | ||||

| Median OS, months | 7·5 | 5·4 | 14·5 | 7·8 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 0·76 (0·38–1·55) | 0·56 (0·26–1·20) | ||||

CR, complete response; CRu, unconfirmed complete response; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

P value versus comparator (Fisher exact test).

Figure 2.

Progression‐free survival (PFS) in patients with aggressive B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (determined by central review) receiving study treatment as 3rd or 4th line with (A) or without (B) previous rituximab treatment.

Similar results were found in the 41 patients who had not previously received rituximab (Table 3). Treatment with pixantrone was associated with better response in terms of rate of CR or CRu (15·0% with pixantrone vs. 4·8% with comparator at the end of treatment, P = 0·343) and ORR (45% vs. 14·3%, P = 0·043). In the 40 patients without previous rituximab receiving the study treatment as a 3rd or 4th line therapy, the PFS was 6·1 vs. 3·5 months for comparator (HR 0·36, 95% CI 0·18–0·73) (Table 3, Fig 2B).

The safety profile of pixantrone in patients with aggressive B‐cell NHL was in line with the previously published results of the main study (Pettengell et al, 2012) and current knowledge on the agent. Uncomplicated neutropenia was more common in the pixantrone group than in the comparator group: all grades represented 50·0% pixantrone vs. 23·9% comparator; grades 3 or 4 represented 41·2% pixantrone, 19·4% comparator. These adverse events were noncumulative and generally lasted less than 3 d. Grade 4 neutropenia occurred at a rate of approximately 10% per cycle with no increase in later cycles. Adjunctive therapy with granulocyte colony stimulating factor was not required in any patient. Other grade 3 or 4 haematological adverse events including leukopenia (23·5% pixantrone, 7·5% comparator) and thrombocytopenia (11·8% pixantrone, 10·4% comparator) were more frequent in the pixantrone group. As regards non‐haematological adverse events, all‐grade diarrhoea was reported more frequently with comparator (4·4% pixantrone, 17·9% comparator) and all‐grade cough with pixantrone (22·1% pixantrone, 4·5% comparator). The rate of cardiac events did not increase with increasing pixantrone exposure and were predominantly asymptomatic (grade 1 and 2 declines in LVEF).

Discussion

Our post hoc analysis confirms the efficacy of pixantrone in patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive B‐cell NHL with up to 3 prior therapeutic regimens and demonstrates concordance for efficacy data even when the histological diagnosis was performed locally and confirmed by an independent histological review (Pettengell et al, 2012). Monotherapy with pixantrone is more effective than physicians' choice of therapy in the 3rd or 4th line (histologically confirmed disease by central review) setting with a CR or CRu of 23·1% vs. 5·1% (P = 0·047) with comparator and an ORR of 43·6% vs. 12·8% with comparator (P = 0·05), independently of whether or not they had previously received rituximab. The good response rate with pixantrone was mainly due to CR (as opposed to CRu) with 17·9% with pixantrone vs. 0% with comparator (P = 0·012). In those who had previously received rituximab, the rate of ORR was 45·0% with pixantrone vs. 11·1% for comparator (P = 0·033) and the rate of CR or CRu was 30·0% vs. 5·6% with comparator (P = 0·093). The better PFS observed in patients with aggressive B‐cell NHL identified by central review compared with when disease was determined by site (HR, 0·52 vs. 0·83; data not shown) suggests that the superior efficacy of pixantrone in the patients with prior rituximab was not due to inclusion of more patients with indolent disease based on site pathology. The rate of CR or CRu in the pixantrone group was almost double that of comparator in the patients with prior rituximab treatment (20·0% vs. 11·5% in patients receiving pixantrone at any line of treatment), demonstrating the validity of pixantrone as a salvage treatment. The observation of efficacy in patients previously treated with rituximab is noteworthy, given that in many other studies, receipt of prior rituximab therapy substantially decreased the response rate to salvage therapies (Gisselbrecht et al, 2010). There was a non‐statistically significant trend towards improved OS in patients treated with pixantrone that appeared to be influenced by the number of prior regimens.

Pixantrone is conditionally approved by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of multiply relapsed or refractory aggressive B‐cell NHL. It was designed from the structure of the anthracyclines with the intention of reducing cardiotoxicity and maintaining antineoplastic efficacy. Pixantrone is an aza‐anthracenedione (Volpetti et al, 2014) with a different mode of action from that of the anthracyclines. Thus, it forms stable DNA adducts thereby preventing DNA replication, transcription and repair (Evison et al, 2007), potentially inhibiting cell division during mitosis (Beeharry et al, 2013). Moreover, by contrast to anthracyclines, pixantrone is less likely to generate reactive oxygen species or form long‐lasting alcohol metabolites because of its inability to bind iron and interact with topoisomerase II, both of which have been linked to the generation of reactive oxygen species and the induction of cardiotoxicity with the anthracyclines (Salvatorelli et al, 2013).

Retreatment of multiply relapsed or refractory patients with aggressive NHL anthracyclines is problematic due to long‐term cardiotoxicity (Chatterjee et al, 2010). The use of anthracycline‐based regimens is associated with a 22% cumulative 10‐year risk for cardiovascular disease, notably with an excess of risk for cardiomyopathy leading to chronic heart failure (incidence ratio 5·4) and stroke (incidence ratio 1·8) (Moser et al, 2006). There were no cumulative dose‐related declines in cardiac function with pixantrone, and the adverse events reported were manageable and similar to the results of the main trial (Pettengell et al, 2012).

The centralized histological review was a strength of the main study (Pettengell et al, 2012) and enabled post hoc analysis of the efficacy of pixantrone in the exact population for which it is intended in clinical practice. The concordance between on‐site histology and retrospective central review (76%) was consistent with rates reported in the literature, which range from 58% to 84% (Jones et al, 1977; Stel et al, 1989; Matasar et al, 2012), reinforcing both the results of the main study and the post hoc analysis.

The small size of the population represents the main limitation of our analysis. Stratified analyses were not conducted for the analyses in this report due to the small strata sizes and the resulting complications with the statistical analyses. This unplanned post hoc analysis was not specifically designed or powered to test the treatment effects in these subgroups. The analysis was not adjusted for differences in baseline characteristics and there was no correction for multiplicity. Further studies are therefore important to confirm our results.

In conclusion, pixantrone is more effective than comparator in relapsed or refractory aggressive B‐cell NHL in the 3rd or 4th line setting, independently of previous rituximab therapy. Pixantrone is an effective treatment that is conditionally approved in the European Union for patients with multiply relapsed and refractory aggressive B‐cell NHL where there is no standard therapy available. Thus, pixantrone offers an efficient treatment alternative for these patients. The efficacy of pixantrone versus gemcitabine both in combination with rituximab is currently being studied in an international phase 3 trial (NCT01321541) in patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL or DLBCL transformed from follicular lymphoma, who have all received previous therapy with R‐CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) or equivalent. The clinical results of this trial are expected in 2016.

Authorship

All authors participated equally in the design of the study, the analysis of the results and the preparation of the report. We thank Sarah Novack, PhD, who provided medical writing assistance on behalf of Servier, France.

Disclosures

RP, CS, PLZ, HGD and BC have received honoraria, research grants, or both from Servier or Cell Therapeutics Inc.; JWS, PT and LW are employees of Cell Therapeutics Inc.; MP and KMM are employees of Servier. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity in conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by CTI.

References

- Beeharry, N. , Zhu, X. , Murali, V. , Smith, M.R. & Yen, T. (2013) Pixantrone induces cell death through mitotic perturbations and subsequent aberrant cell divisions in solid tumor cell lines. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 12, A147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, E.M. & Morschhauser, F. (2015) Pixantrone: a novel anthracycline‐like drug for the treatment of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma. Expert Opinon on Drug Safety, 14, 601–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao, M.P. (2013) Treatment challenges in the management of relapsed or refractory non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma ‐ novel and emerging therapies. Cancer Management and Research, 5, 251–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, K. , Zhang, J. , Honbo, N. & Karliner, J.S. (2010) Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Cardiology, 115, 155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheson, B.D. , Horning, S.J. , Coiffier, B. , Shipp, M.A. , Fisher, R.I. , Connors, J.M. , Lister, T.A. , Vose, J. , Grillo‐Lopez, A. , Hagenbeek, A. , Cabanillas, F. , Klippensten, D. , Hiddemann, W. , Castellino, R. , Harris, N.L. , Armitage, J.O. , Carter, W. , Hoppe, R. & Canellos, G.P. (1999) Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non‐Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 17, 1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheson, B.D. , Pfistner, B. , Juweid, M.E. , Gascoyne, R.D. , Specht, L. , Horning, S.J. , Coiffier, B. , Fisher, R.I. , Hagenbeek, A. , Zucca, E. , Rosen, S.T. , Stroobants, S. , Lister, T.A. , Hoppe, R.T. , Dreyling, M. , Tobinai, K. , Vose, J.M. , Connors, J.M. , Federico, M. & Diehl, V. (2007) Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coiffier, B. , Thieblemont, C. , Van Den Neste, E. , Lepeu, G. , Plantier, I. , Castaigne, S. , Lefort, S. , Marit, G. , Macro, M. , Sebban, C. , Belhadj, K. , Bordessoule, D. , Ferme, C. & Tilly, H. (2010) Long‐term outcome of patients in the LNH‐98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab‐CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood, 116, 2040–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evison, B.J. , Mansour, O.C. , Menta, E. , Phillips, D.R. & Cutts, S.M. (2007) Pixantrone can be activated by formaldehyde to generate a potent DNA adduct forming agent. Nucleic Acids Research, 35, 3581–3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselbrecht, C. , Glass, B. , Mounier, N. , Singh, G.D. , Linch, D.C. , Trneny, M. , Bosly, A. , Ketterer, N. , Shpilberg, O. , Hagberg, H. , Ma, D. , Briere, J. , Moskowitz, C.H. & Schmitz, N. (2010) Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B‐cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 4184–4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.E. , Butler, J.J. , Byrne, G.E. Jr , Coltman, C.A. Jr & Moon, T.E. (1977) Histopathologic review of lymphoma cases from the Southwest Oncology Group. Cancer, 39, 1071–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matasar, M.J. , Shi, W. , Silberstien, J. , Lin, O. , Busam, K.J. , Teruya‐Feldstein, J. , Filippa, D.A. , Zelenetz, A.D. & Noy, A. (2012) Expert second‐opinion pathology review of lymphoma in the era of the World Health Organization classification. Annals of Oncology, 23, 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser, E.C. , Noordijk, E.M. , van Leeuwen, F.E. , le Cessie, S. , Baars, J.W. , Thomas, J. , Carde, P. , Meerwaldt, J.H. , van Glabbeke, M. & Kluin‐Nelemans, H.C. (2006) Long‐term risk of cardiovascular disease after treatment for aggressive non‐Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood, 107, 2912–2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettengell, R. , Coiffier, B. , Narayanan, G. , de Mendoza, F.H. , Digumarti, R. , Gomez, H. , Zinzani, P.L. , Schiller, G. , Rizzieri, D. , Boland, G. , Cernohous, P. , Wang, L. , Kuepfer, C. , Gorbatchevsky, I. & Singer, J.W. (2012) Pixantrone dimaleate versus other chemotherapeutic agents as a single‐agent salvage treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive non‐Hodgkin lymphoma: a phase 3, multicentre, open‐label, randomised trial. The Lancet. Oncology, 13, 696–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatorelli, E. , Menna, P. , Paz, O.G. , Chello, M. , Covino, E. , Singer, J.W. & Minotti, G. (2013) The novel anthracenedione, pixantrone, lacks redox activity and inhibits doxorubicinol formation in human myocardium: insight to explain the cardiac safety of pixantrone in doxorubicin‐treated patients. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 344, 467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stel, H.V. , Vroom, T.M. , Blok, P. , van Heerde, P. & Meijer, C.J. (1989) Therapy‐relevant discrepancies between diagnoses of institutional pathologists and experienced hematopathologists in the diagnosis of malignant lymphoma. Pathology, Research and Practice, 184, 242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpetti, S. , Zaja, F. & Fanin, R. (2014) Pixantrone for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive non‐Hodgkin B‐cell lymphomas. OncoTargets and Therapy, 7, 865–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]