Abstract

The kinetic behaviour of the photo-induced copper(I) catalyzed azide—alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction was studied in detail using real-time Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) on both a solvent-based monofunctional and a neat polymer network forming system. The results in the solvent-based system showed near first-order kinetics on copper and photoinitiator concentrations up to a threshold value in which the kinetics switch to zeroth-order. This kinetic shift shows that the photo-CuAAC reaction is not suseptible from side reactions such as copper disproportionation, copper(I) reduction, and radical termination at the early stages of the reaction. The overall reaction rate and conversion is highly dependent on the initial concentrations of photoinitiator and copper(II), as well as their relative ratios. The conversion was decreased when an excess of photoinitiator was utilized compared to its threshold value. Interestingly, the reaction showed an induction period at relatively low intensities. The induction period is decreased by increasing light intensity, and photoinitiator concentration. The reaction trends and limitations were further observed in a solventless polymer network forming system, exhibiting a similar copper and photoinitiator threshold behaviour.

1 Introduction

Click chemistry refers to a set of high yielding and selective reactions with limited or easily removable byproducts which proceed under simple reaction conditions1. In addition to the ease and versatility associated with these reactions, a few click reactions are initiated by light, affording spatiotemporal control of product formation. One of the most widely used click reactions is the copper(I) catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction2,3. In the CuAAC reaction, the copper(I) catalyst is typically introduced by the in situ reduction of copper(II) into copper(I)4,5 or by the direct addition of copper(I) salt in the presence of a base which immediately triggers the azide–alkyne cycloaddition reaction6,7. Despite its utility in applications requiring bio-orthogonal reactions8,9, the CuAAC reaction had previously lacked the temporal control characteristic of other photo-enabled click reactions, such as the thiol-ene10 and thiol-yne11,12 radical mediated reactions as well as the photocaged-base-thiol-Michael addition13.

In the last decade, there have been considerable efforts to trigger the CuAAC reaction using light. One of the most straightforward routes is to simply reduce the copper catalyst from copper(II) to copper(I) using a photochemical scheme. Ritter and König were the first to reduce copper(II) using a photosensitizing system14, which was later extended to non-aqueous conditions by Tasdelen and Yagci15. The photo-CuAAC reaction was further demonstrated in systems capable of undergoing a light-initiated CuAAC polymerization by Adzima et al16. thereby enabling photolithography and photofunctionalization17.

Despite the impact of the photo-CuAAC reaction in bioconjugation and more broadly in materials systems, the kinetic behaviour and the limitations of this reaction are still relatively unexplored. Mainly, understanding how and why the copper catalyst, photoinitiator, and light intensity affect its rate in monofunctional, solvent-based systems as well as network forming systems is critical for practical applications of this reaction. In the work presented here, we investigate the reaction conditions that affect photo-CuAAC kinetics and examine its limitations. We identify the key variables associated with the photo-CuAAC reaction and provide insight in controlling the reaction rate and extent. Moreover, these results are shown in both solvent based model systems and polymer network-forming reactions, thus demonstrating their broad applicability. Importantly, the reaction kinetics show distinct and unique behaviour as compare to the traditional, non-photo CuAAC reaction. Overall, both the quantitative and qualitative trends contained herein will inform users of the photo-activated CuAAC reaction of suitable reaction conditions for applications in both solution-based systems and polymer networks.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

The following chemical compounds were used without further purification: 1-dodecyne (Sigma Aldrich), methyl 2-azidoacetate (Sigma Aldrich), copper Sulphate pentahydrate (Sigma Aldrich), bis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzyoyl)-phenylphosphineoxide (Irgacure 819) (Ciba), N,N-dimethylforamamide (Fisher Scientific), N,N,N′,N′,N″-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (Sigma Aldrich), copper chloride (Sigma Aldrich).

2.2 Monitoring Reaction Kinetics

A Nicolet Nexus 670 Series Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer was used in conjugation with a SL-2 sealed liquid cell equipped with calcium fluoride windows (International Crystal Laboratories). Solutions containing the reactants, 1-dodecyne and methyl 2-azidoacetate, the copper catalyst (CuSO4•5H2O), and Irgacure-819 were prepared in DMF and stirred for at least 30 minutes. The reaction system is depicted in Scheme 1. Typical reaction systems contained 110 mM of 1-dodecyne and methyl 2-azidoacetate and 10 mM of copper(II) and photoinitiator. Aliquots of the reaction system were injected in the liquid cell which was then mounted on the FTIR. After 30 seconds the liquid cell was irradiated using an OmniCure Series 2000 lamp, that was filtered using a 405 nm band pass interference filter, equipped with a 200 Watt mercury arc bulb (Lumen Dynamics), which started the reaction. The reaction kinetics were monitored via the reduction of the methyl 2-azidoacetate (azide) peak between 2080 and 2150 cm−1 which exhibits a maximum at 2109 cm−1 (see supplementary information, Fig S1). Using a Beer’s Law type analysis, the area under the peak is directly proportional to the concentration of the species at a constant path length which was constant throughout the experiments at 0.1 mm. The decrease in the concentration of methyl 2-azidoacetate over the first two minutes of the reaction represented an average initial rate of the reaction and was calculated for each sample. All rate law experiments were performed in triplicate.

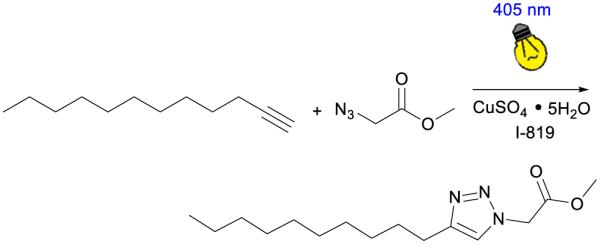

Scheme 1.

Photo-CuAAC reaction system: 1-dodecyne reacts with methyl 2-azidoacetate in the presence of copper Sulphate pentahydrate and Irgacure 819 in DMF under 405 nm incident light to produce the triazole product.

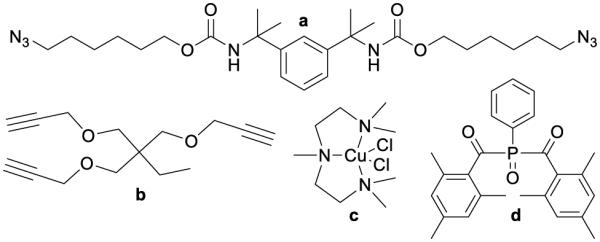

2.3 Polymerizations

The polymer application experiments used bis(6-azidohexyl)(1,3-phenylenebis(propane-2,2-diyl))dicarbamate (monomer 1; Fig 1a), and 1-(Prop-2-ynyloxy)-2,2-bis(prop-2-ynyloxymethyl)butane (monomer 2; Fig 1b) which were synthesized from literature procedures found in [18] and [17] respectively and their structure confirmed by NMR (see supplementary information, Fig S2,S3). The reactants were mixed stoichiometrically with respect to the azide and alkyne functional groups. A copper chloride N,N,N′,N′,N″-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA) ligand was synthesized19 to act as the copper(II) source (Fig 1c) and dissolved in trace (<1wt%) methanol. Irgacure 819 was used as the photoinitiator (Fig 1d). The components were mixed under high speed using a DAC 150.1 FVZ-K Flacktek Speed Mixer. The conversion in these experiments were monitored via the alkyne near-IR peak between 6430 and 6570 cm−1 where the trialkyne has a peak at 6507 cm−1 (see supplementary information, Figure S3)20. All polymer samples were placed between glass slides and separated with a spacer of 0.12 mm thickness. The structure of the monomers, catalyst and photoinitiators used in the polymerization system is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Monomers, catalyst and photoinitiators used in the polymerization system. (a) bis(6-azidohexyl)(1,3-phenylenebis(propane-2,2-diyl))dicarbamate (b) 1-(Prop-2-ynyloxy)-2,2-bis(prop-2-ynyloxymethyl)butane (c) CuCl2/PMDETA (d) Irgacure 819

3 Results and Discussion

The reaction kinetics and mechanism for the CuAAC reaction have been studied in detail since its discovery in 2002. Depending on the concentration of copper, the reaction rate dependence on reactant concentration follows one of two behaviours: first-order rate dependence on the azide and alkyne concentrations at non-catalytic copper concentrations and roughly zero-order rate dependence on azide and alkyne concentration when copper is at catalytic concentrations21.

The observed second-order scaling in copper at catalytic concentrations has led to the hypothesis that a dinuclear copper intermediate is formed, which has been supported by DFT calculations22 and, more recently, by direct experimental evidence23,24. Copper(II) is typically formed in situ from copper(I) using an excess of a reducing agent, such as sodium ascorbate, which also helps in alkyne deprotonation25. It has been shown that the reducing agent does not influence the kinetics of the reaction and can be used in large excess, suggesting that the production of copper(I) is not limiting in these traditional CuAAC reactions26. Introducing photoinitiation to the CuAAC system can have several potential effects on the reaction pathway (Scheme 2). Upon incident irradiation, a photoinitiator (PI) will form radicals (R•) that will subsequently undergo several presumed reactions. (1) The radical could react with oxygen (O2), forming a peroxy radical as is prevalent in free radical polymerizations. These peroxy radicals have a much lower reducing potential than benzoyl or phosphinoyl radicals and would slow the reaction rate27. While oxygen inhibition is common in polymers involving phosphinoyl radicals28, at both low and high intensities oxygen was not observed to inhibit the photo-CuAAC system (see supplementary information, Fig S4). (2) The radical could react with another radical to undergo radical-radical termination (i.e., radical recombination). This reaction pathway is limited by the concentration of radicals produced at a certain time. (3) If the redox potential of the radical is sufficient, it can reduce copper(II) to copper(I), which will then enter the CuAAC reaction cycle as a catalyst; this the ideal or desired reaction pathway to initiate the CuAAC reaction. (4) Similarly, the radical can further reduce copper(I) to copper(0). Beyond side reactions of radicals, (5) copper(I) can undergo copper disproportionation in which two copper(I) molecules will react, forming copper(II) and copper(0)29. (6) Finally, azide decomposition under UV or near UV-light is a potential reaction pathway in which the azide forms a reactive nitrene and nitrogen gas30,31, With respect to this latter mechanism, methyl 2-azidoacetate was observed to not undergo significant decompositions in DMF when exposed to 405 nm light for 100 minutes of the reaction (see supplementary information, Fig S5).

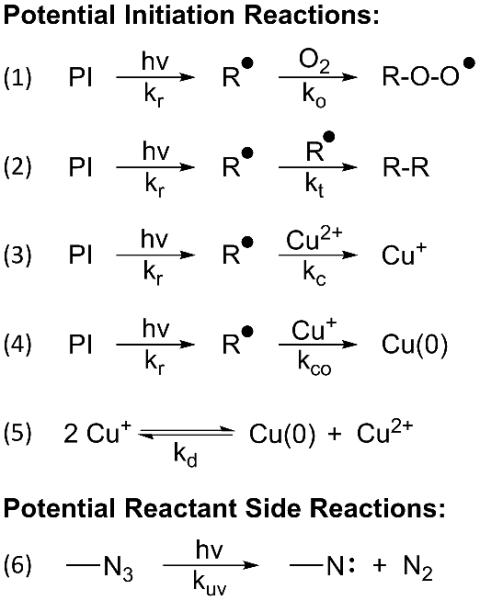

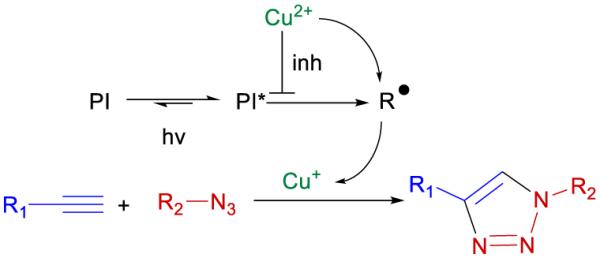

Scheme 2.

Potential reactions involved in photoinitiating the CuAAC reaction. Once the radicals are generated through light irradiation, they can either (1) react with oxygen forming peroxy radicals, (2) terminate by reacting with other radicals, or (3) reduce copper(II) into copper(I). (4) Copper(I) could then either be reduced further to form copper(0) or (5) react with another copper(I) molecule to yield copper(II) and copper(0) via disproportionation. (6) Finally, the azide could decompose into nitrene and nitrogen gas under UV or near UV-light.

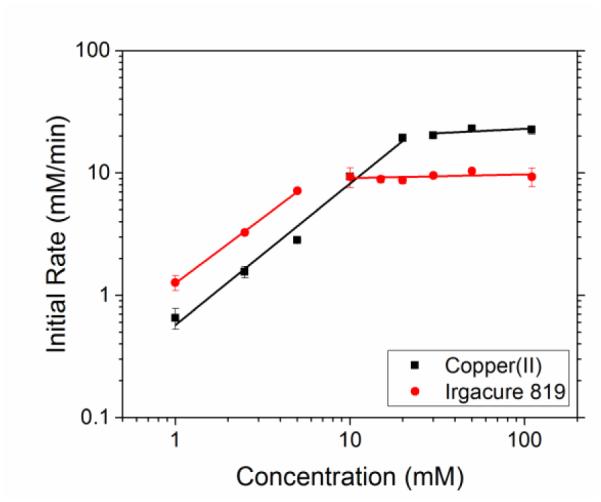

Rate law studies, where key components of the photo-CuAAC reaction are varied, reveal kinetic behaviour that is different than that observed in traditional CuAAC reactions. While azide and alkyne concentration variations predictably had a negligible effect on the reaction rate, which is consistent with CuAAC kinetic behaviour in the absence of accelerating ligands21 (see supplementary information, Fig S6,S7), the copper concentration reaction dependence yields a near first-order scaling (1.15 ± 0.08) for lower concentrations as shown in Figure 2. While the first-order scaling in copper concentration is atypical for a CuAAC reaction, similar scaling has been previously observed where an accelerating ligand is included. This behaviour was attributed to weak-donor environments in which the binuclear copper-ligand complex remains intact32. In our system, it is unlikely that the first-order scaling is attributed to the reaction environment as DMF would constitute a strong-donor environment. Interestingly, the first-order scaling in copper has also been reported in other photo-initiated CuAAC reaction schemes. For example, Ritter and König reported a first-order scaling in copper(I) concentrations using dihydroflavin as a photoreducing agent14. Song et al. furthermore found a first-order dependence in copper concentrations using bulk photo-initiated CuAAC chemistries18. This scaling appears characteristic of photo-CuAAC reaction schemes that utilize an in situ photoinitiator. At higher concentrations of copper(II), once the initial copper (II) concentration is roughly double the initial photoinitiator, there is an abrupt transition to near zeroth-order kinetics. A scaling of (0.07 ± 0.08) with respect to initial copper (II) concentration is observed in this regime. We define the threshold value as the concentration in which the kinetics switches from first-order to zeroth-order. This transition likely accompanies the transition of copper(II) to a limiting reactant with respect to the photoinitiator. It also would imply that the formation of copper(I) is largely irreversible, as excess amounts are not required to continuously reduce the copper(II) back to copper(I). Furthermore, the zeroth-order kinetics copper(II) concentration threshold suggests that copper disproportionation (Scheme 2, reaction 5) is slow relative to the photo-CuAAC reaction, since the addition of excess initial copper(II) would have shifted the equilibrium towards copper(I) formation and resulted in an increasing reaction rate rather than a zero-order plateau.

Figure 2.

Copper and Irgacure 819 kinetic scaling effects. Varying copper(II) concentration (square) at constant photoinitiator concentration at 10 mM and varying photoinitiator concentration at constant copper concentration (circle) at 10 mM at 5 mW/cm2 of 405 nm light. The concentrations of 1-dodecyne and methyl 2-azidoacetate were kept constant at 110 mM. Copper(II) scaled to (1.15 ± 0.08) between 1 and 20 mM and shifted to (0.07 ± 0.08) beyond 20 mM. Irgacure 819 scaled to (1.07 ± 0.03) between 1 and 5 mM and shifted to (0.03 ± 0.03) beyond 5 mM.

Figure 2, further reveals that the role of the photoinitiator on the kinetics of the photo-CuAAC system is dissimilar from a copper(II) reducing agent typically employed in CuAAC reactions. Again, a near first-order rate scaling of (1.07 ± 0.03) on the initial photoinitiator concentration is observed until a threshold of 5 mM photoinitiator is reached, where the scaling shifts to (0.03 ± 0.03). This transition to zero-order kinetics implies that copper(II) has become the limiting initial reagent. This scaling is similar to the behaviour observed above with varying initial copper(II) concentrations, and in this case the zero-order reaction rate threshold suggests that further reduction of copper(I) to copper(0) by reaction with radicals (Scheme 2, reaction 4) is not significant. If further reduction was important to the initial kinetics, increasing the amount of photoinitiator would have decreased the initial reaction rate. The protection of the copper(I) species from further reduction could be due to the formation of a stable copper(I)-acetylide complex or the triazole acting as a ligand. While radical-radical termination (Scheme 2, reaction 2) is most likely occurring at increased concentrations of photoinitiator, it also does not appear to affect the initial rate of the photo-CuAAC reaction. If this recombination reaction were influencing the initial rate of the photo-CuAAC reaction, an increase in initial photoinitiator concentrations would have decreased the initial reaction rate.

Figure 2 clearly demonstrates that the kinetic behaviour is dictated by the amount and relative ratio of copper(II) and photoinitiator concentrations in the system. As discussed, several radical side reactions do not influence the rate of the reaction where the initial rate in a photo-CuAAC system is dependent on the formation of copper(I) via the reduction of copper(II) with photoinitiator radicals (Scheme 2, reaction 3), which is justified through the threshold values obtained above. The threshold value in copper(II) concentration is always double the concentration of Irgacure 819, while the threshold value of Irgacure 819 is always half the concentration of copper(II) in the system, as depicted in Figure 3a and b. This indicates that one photoinitiator molecule is capable of reducing two copper(II) molecules to copper(I) in our system, which is consistent with the capability of Irgacure 819 to cleave into four radicals33, including two phosphinoyl radicals which have a strong copper(II) reducing potential. Moreover, the kinetics of the process are enhanced by increasing the concentration of copper(II) and photoinitiator given that the ratio between them remains constant (Figure 3c).

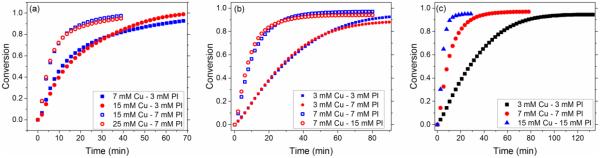

Figure 3.

Copper(II)/Irgacure-819 ratio effects on the photo-CuAAC reaction using 110 mM methyl-2azidoacetate and 1-dodecyne in DMF at 10 mW/cm2 (405 nm filtered light). (a) Adding copper(II) above its threshold value does not influence the reaction kinetics. Similar kinetic behavior is observed when the concentration of photoinitiator is constant at 3 mM and copper(II) is increased from 7 mM to 15 mM (closed square and circle). The reaction rate of 25 mM of copper(II) and 15 mM of copper(II) at constant photoinitiator concentration at 7 mM is also the same (open square and circle). (b) Adding photoinitiator above its threshold value does not increase the reaction rate. The reaction rate of 3 mM Copper(II) with 3 and 7 mM of I-819 are identical (closed square and circle). The reaction rate of 7 mM Copper(II) with 7 and 15 mM of I-819 are also identical (open square and circle). (c) When both copper(II) and I-819 are increased in an equimolar ratio from 3 mM copper(II) and 3 mM I-819 (square) to 7mM copper(II) and 7 mM I-819 (circle) to 15 mM copper(II) and 15 mM I-819 (triangle), the reaction rate increases.

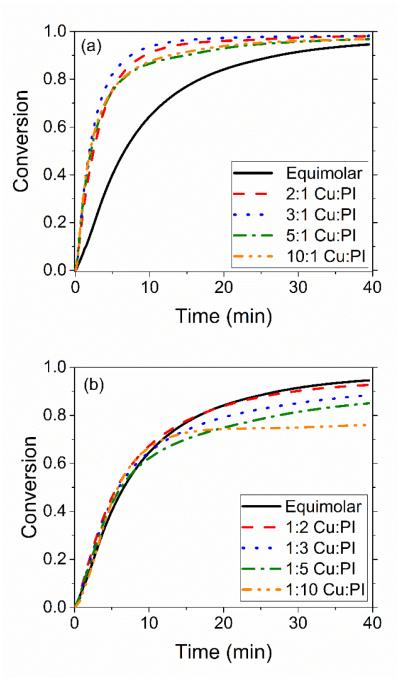

While the initial rates of the photo-CuAAC reaction are unchanged beyond the copper(II) and photoinitiator threshold values, the overall conversion of the reaction system is affected by the relative copper(II) to photoinitiator ratios present in the system. Increasing the concentration of initial copper(II) in the system above a threshold value of photoinitiator in the system does not affect the overall conversion of the reaction (Figure 4a). This implies that disproportionation reactions play no significant role in the photo-CuAAC reaction. However, increasing the amount of photoinitiator relative to the copper(II) concentration threshold has a deleterious effect on the overall conversion (Figure 4b). We hypothesize that excess photoinitiator is reacting with copper(I) to form copper(0) at a later stage of the reaction (i.e., scheme 2, reaction 4); when a large excess of photoinitiator molecules was used, the solution turned a dark brown color after irradiating which is indicative of copper(0) formation. Increased radical recombination as the reaction progresses may also be occurring due to the large excess of photoinitiator radicals at high intensities. Indeed, when increasing the concentration of photoinitiator 40 times that of initial copper(II), the reaction exhibits a drastic decrease in the overall conversion where it plateaued at 20% conversion after only 25 minutes of reaction time (see supplementary information, Fig S8). This further illustrates how the photoinitiator interaction with copper is different than an in situ reducing agent such as sodium ascorbate, which can be used in excessive quantities 2,22,34.

Figure 4.

Final conversion effects of increasing copper(II) and photoinitiator concentrations in a photo-CuAAC system. (a) At a constant 1-dodecyne and methyl 2-azidoacetate concentration at 110 mM and Irgacure 819 concentration at 10 mM, adding copper between 10 mM and 100 mM resulted in a final conversion that ranged between 94 and 98%. (b) At a constant 1-dodecyne and methyl 2-azidoacetate concentration at 110 mM and copper(II) concentration at 10 mM, adding Iragacure-819 in the system between 10 mM 100 mM decreased the final conversion from 94% to 76% after 40 minutes.

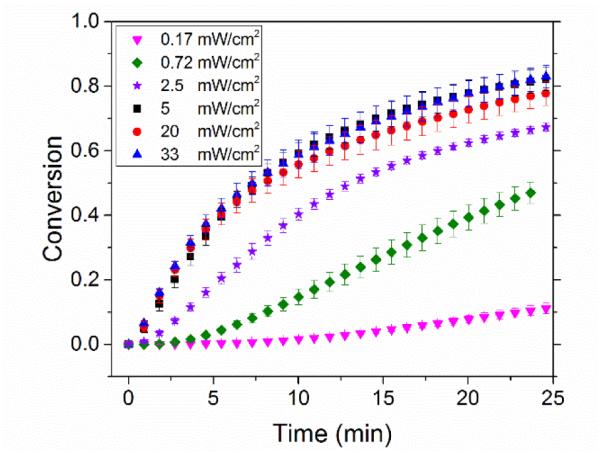

The photo-CuAAC reaction exhibits two different behaviours depending on the light intensity used (Fig. 5). In the high intensity regime, the kinetic behaviour, threshold values, and scaling of copper(II) and photoinitiator are unchanged as a function of intensity (see supplementary information, Fig S9,S10). Intensity directly impacts the rate of photolysis and thus the rate of radical formation in conventional photopolymerizations. Since the selected intensity only affects the rate of radical formation, the reaction rate independence at and above 5 mW/cm2 indicates that the rate determining step is not the rate of radical formation, but rather the CuAAC cycle itself. For lower intensities, however, the photoreduction must be occurring at similar or slower rates to the CuAAC reaction, and thus the overall reaction rate has a much more complex dependence on the initial copper(II) and photoinitiator concentrations. Consequently, the copper(II) and photoinitiator scaling is altered, and furthermore the characterization of the reaction in terms of the initial ratio of copper(II) to photoinitiator is no longer possible.

Figure 5.

The effects of varying intensity on the initial rate of the photo-CuAAC reaction. The concentration of Irgacure 819 and copper(II) were 10 mM and the concentration of 1-doedecyne and methyl 2-azidoacetate were constant at 110 mM each. The intensity did not significantly influence the kinetics above 5 mW/cm2.

In the low intensity regime, the photo-CuAAC system exhibits a delay before the onset of the decrease in azide concentration. While this induction period has been observed in other photo-CuAAC systems, it had been generally attributed to potential oxygen inhibition effects35. Through argon purging experiments, there was no evidence of oxygen inhibition in our samples at low intensities (see supplementary information, Fig S11). The induction period at low intensities could moreover be attributed to the slow kinetics of radical formation at low intensities; the photo-CuAAC reaction would require a build-up of radicals to convert copper(II) to copper(I). This is, however, unlikely since the kinetics of copper(II) to copper(I) conversion in the presence of phosphinoyl radicals for photo-CuAAC reactions was found to be extremely rapid36. Furthermore, this period may be an indication that the triazole product acts as a ligand for the copper(I) species; once a small amount of triazole forms, autoacceleration of the reaction is achieved due to the stable copper(I) ions formed. Alternatively, an induction time has been observed in traditional CuAAC reactions, which was attributed to the nature of the copper-ligand and copper-anion interactions with the alkyne species as discussed by Jin et al.37 Finally, a relatively simple explanation of the induction period is that the copper(II) is quenching of the photoinitiating system. Therefore, as copper(II) is converted to copper(I), the reaction rate would accelerate as suggested in Scheme 3. It should be noted that the quenching of photoinitiating ketones by metal cations (including copper cations) has been reported in literature38,39.

Scheme 3.

Suggested photoinitiation scheme in which the copper(II) source can quench the photoinitiator triplet state (PI*) before it forms radicals. Once this inhibition is overcome, the photoinitiator (PI) can form radicals (R•) which then reduce copper(II) to copper(I) catalyzing the CuAAC reaction.

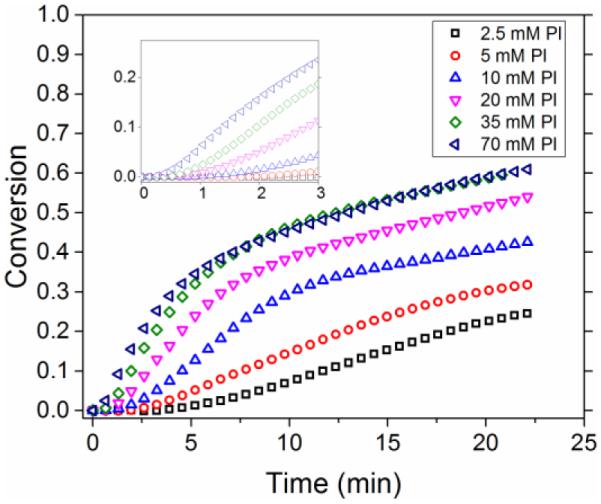

The induction period appears to be dependent on the absorbency and quantum yield of the photoinitiator used in a photo-CuAAC reaction as discussed by Tasdelen et al.40. This would explain why the induction period is significantly reduced by increasing photoinitiator concentrations. Indeed, increasing the concentration of the photoinitiator increased the rate of radical generation which effectively shifts the intensity-driven threshold values as shown in Figure 6. While adding copper(II) to the monofunctional system did not influence the induction period significantly, an increase in the induction time was observed in the bulk polymer system when the amount of copper was increased at a low intensity (See supplemntary information, Fig S12).

Figure 6.

Photoinitiator concentration effects in the low intensity regime: Varying the concentration of Irgacure 819 from 2.5 mM to 70 mM at a constant copper(II) concentration at 10 mM and methyl 2-azidoacetate and 1-dodecyne constant at 110 mM. The intensity used was 0.5 mW/cm2 of 405 nm filtered light. Increasing the concentration of photoinitiator from 2.5 mM to 70 mM decreased the inhibition time from 3 minutes to less than 15 seconds and increased the reaction rate significantly.

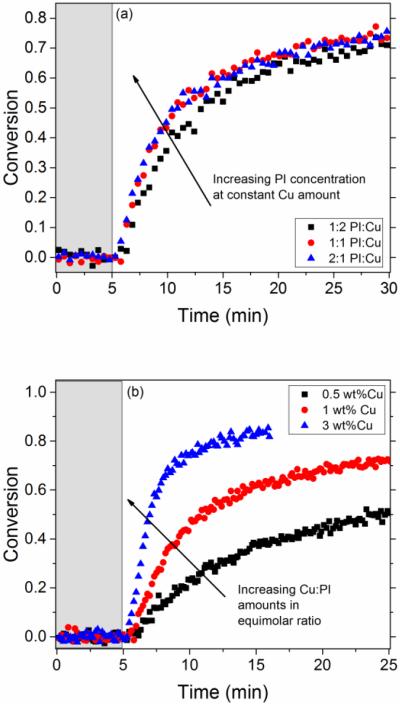

The kinetic trends in these solvent-based, model systems are also observed in solventless, bulk photopolymerizations that use copper ligands to catalyze the CuAAC chemistries. Since copper(II) is not miscible in the neat monomer systems, we use CuCl2-PMDETA along with Irgacure 819 to demonstrate the compositional variation effects in a network forming polymerization (i.e., the photo-CuAAC reaction of monomer 1 and monomer 2). The threshold value effects of Irgacure 819 is demonstrated in Figure 7a, where increasing the concentration of photoinitiator in the system beyond a constant amount of CuCl2-PMDETA (1 wt%) is negligible. However, when both copper(II) and photoinitiator concentrations are increased simultaneously at a 1:1 molar ratio, the kinetics of the reaction are notably increased as depicted in Figure 7b.

Figure 7.

Kinetic results in polymerizing systems using Irgacure 819 and CuCl2-PMDETA along with monomers 1 and 2 as the reactants and at a constant intensity of 10 mW/cm2 of 405 nm wavelength light and a sample thickness of 0.12 mm. The grey, shaded area represents the time (5 min) before the light was turned on. (a) Threshold value in photoinitiator applies in network forming systems. When the concentration of photoinitiator is increased beyond half that of copper(II), from a 1:2 mol ratio Irgacure 819:CuCl2-PMDETA (square) to an equimolar ratio (circle) and then a 2:1 mol ratio (triangle), there was little increase in the reaction rate. (b) When the concentration of photoinitiator and copper(II) where increased in equimolar concentrations from a 0.5 wt% of Copper(II) (square) to 1 wt% Copper(II) (circle) to 3 wt% ratio (triangle)., the rate of the reaction significantly increases.

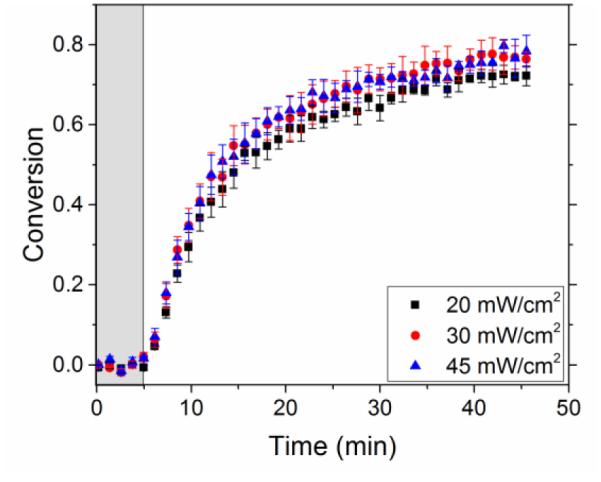

Similar to model systems, the threshold value in intensity is observed in network forming systems, as shown in Figure 8. In contrast to other radical-initiated polymerizations41-43, increasing the light intensity beyond a threshold value does not increase the polymerization rate. In our system this threshold was observed beyond 20 mW/cm2 where the polymerization kinetics become independent of the rate of radical formation.

Figure 8.

Varying intensity in polymer systems using Irgacure 819 and CuCl2-PMDETA along with monomers 1 and 2 as the reactants using 405 nm wavelength and a sample thickness of 0.12 mm. The grey, shaded area represents the time (5 min) before the light was turned on. When the intensity was increased beyond 20 mW/cm2, the reaction rate did not significantly change.

4 Conclusions

The kinetic behaviour of the photo-CuAAC reaction shows two different regimes of behaviour. In the first, the photoreduction of copper(II) is much faster than the kinetics of the CuAAC reaction. Here, the initial reaction rate is increased by increasing the concentrations of the photoinitiator until the photoinitiator is in excess, and zero-order behaviour is observed. Near first-order kinetics is observed in with respect to copper(II) concentrations. Consequently, first-order behaviour is also observed with respect to photoinitiator when copper(II) is in excess. This threshold behaviour is indicative of the robust nature of the photo-CuAAC reaction in this regime as several potential side reactions appear to be largely suppressed and the reaction is highly selective towards forming the desired copper(I) catalyst. However, while using excess photoinitiator in the system does not affect the initial rate, it does significantly decrease the overall conversion of the reaction, implying that further reduction of copper(I) to copper metal does play a role in the kinetics. This behaviour is significantly different from typical in situ reducing agents such as sodium ascorbate, which can be used in large excess when compared to the copper catalyst amount.

In the second regime, the copper(II) reduction reaction appears to occur on a similar timescale to the CuAAC reaction, which significantly complicates the observed behaviour and the scale of the rate law with regards to the initial copper (II) and photoinitiator concentrations. Furthermore, an induction period is observed in these systems which can be significantly decreased by increasing the concentration of the photoinitiator used or the intensity of light. It is hypothesized that the induction period is due to copper(II) quenching of the triplet state of the photoinitiator.

The kinetic trends observed in the solvent system were extended to a solvent-free polymer network system. This photopolymerization shows similar results to the solvent system kinetics, which further emphasizes the importance of the copper and photoinitiator threshold values and its impact on controlling the reaction rate in different photo-CuAAC reaction schemes. While the photochemical reduction used in the photo-CuAAC reaction shares some steps in common with conventional photopolymerizations, the nuances of the CuAAC reaction give it much different behaviour. Unlike radical reactions, the zero order behaviour observed provides some interesting opportunities for applications requiring dark cure post exposure and low intensity curing. Furthermore, while this behaviour does occur in the “high light intensity” regime reported here, it must be noted that these light intensities are one to two orders of magnitude less than that used in many industrial applications. This fact implies that were these materials to show better performance than conventional photopolymers, the curing chemistry should not limit their implementation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support from NIH-NIDCR (U01 DE023774). We thank Dr Jonathan French for extremely helpful discussion and insight in organic chemistry. We also thank Ms. Melissa Gordon for feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Notes and references

- 1.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. The reaction kinetics and mechanism for the CuAAC reaction have been studied in detail since its discovery in 2002. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tornøe CW, Christensen C, Meldal M. The reaction kinetics and mechanism for the CuAAC reaction have been studied in detail since its discovery in 2002. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3057–3064. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bock VD, Hiemstra H, Van Maarseveen JH. European J. Org. Chem. 2006:51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meldal M, Tornøe CW. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2952–3015. doi: 10.1021/cr0783479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith NW, Polenz BP, Johnson SB, Dzyuba SV. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:550–553. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fazio F, Bryan MC, Blixt O, Paulson JC, Wong CH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:14397–14402. doi: 10.1021/ja020887u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolb HC, Sharpless KB. Drug Discov. Today. 2003;8:1128–1137. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02933-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fokin VV. ACS Chem. Biol. 2007;2:775–778. doi: 10.1021/cb700254v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoyle CE, Bowman CN. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2010;49:1540–1573. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fairbanks BD, Scott TF, Kloxin CJ, Anseth KS, Bowman CN. Macromolecules. 2009;42:211–217. doi: 10.1021/ma801903w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan JW, Zhou H, Hoyle CE, Lowe AB. Chem. Mater. 2009;21:1579–1585. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xi W, Peng H, Aguirre-Soto A, Kloxin CJ, Stansbury JW, Bowman CN. Macromolecules. 2014;47:6159–6165. doi: 10.1021/ma501366f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritter SC, König B. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2006:4694–4696. doi: 10.1039/b610696j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tasdelen MA, Yagci Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:6945–6947. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adzima BJ, Tao Y, Kloxin CJ, DeForest CA, Anseth KS, Bowman CN. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:256–259. doi: 10.1038/nchem.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong T, Adzima BJ, Baker NH, Bowman CN. Adv. Mater. 2013;25:2024–2028. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song HB, Baranek A, Bowman CN. Polym. Chem. 2016;7:603–612. doi: 10.1039/c5py01655j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margraf G, Bats JW, Wagner M, Lerner HW. Inorganica Chim. Acta. 2005;358:1193–1203. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Workman J, Weyer L. Practical Guide to Interpretive Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodionov VO, Fokin VV, Finn MG. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2005;44:2210–2215. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Himo F, Lovell T, Hilgraf R, Rostovtsev VV, Noodleman L, Sharpless KB, Fokin VV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:210–216. doi: 10.1021/ja0471525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Worrell BT, Malik JA, Fokin VV. Science (80-. ) 2013;340:457–460. doi: 10.1126/science.1229506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin L, Tolentino DR, Melaimi M, Bertrand G. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500304–e1500304. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buckley BR, Dann SE, Heaney H. Chem. - A Eur. J. 2010;16:6278–6284. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodionov VO, Presolski SI, Díaz DD, Fokin VV, Finn MG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12705–12712. doi: 10.1021/ja072679d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buettner GR, Jurkiewicz BA. Radiat. Res. 1996;145:532–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jockusch S, Turro NJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:11773–11777. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gagne R, Allison J, Gall R, Koval C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:7170–7178. doi: 10.1021/ja00464a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moriarty RM, Reardon RC. Tetrahedron. 1970;26:1379–1392. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shete A, El-Zaatari B, French J, Kloxin C. Chem. Commun. (Camb) doi: 10.1039/c6cc05095f. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Presolski SI, Hong V, Cho SH, Finn MG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14570–14576. doi: 10.1021/ja105743g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolczak U, Rist G, Dietliker K, Wirz J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:6477–6489. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi L, Jing C, Ma W, Li D-W, Halls JE, Marken F, Long Y-T. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2013;52:6011–6014. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gong T, Adzima BJ, Bowman CN. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2013;49:7950–2. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43637c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yagci Y, Tasdelen MA, Jockusch S. Polym. (United Kingdom) 2014;55:3468–3474. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin L, Romero E. a, Melaimi M, Bertrand G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015 doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11028. jacs.5b11028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishiguchi H, Anpo M. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 1994;77:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osawa Z. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1988;20:203–236. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tasdelen MA, Yilmaz G, Iskin B, Yagci Y. Macromolecules. 2012;45:56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lecamp L, Youssef B, Bunel C, Lebaudy P. Polymer (Guildf) 1997;38:6089–6096. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lovell LG, Newman SM, Bowman CN. J. Dent. Res. 1999;78:1469–1476. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780081301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scherzer T, Decker U. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. with Mater. Atoms. 1999;151:306–312. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.