Abstract

Synthetic cannabinoids (SCs) are an emerging class of abused drugs that differ from each other and the phytocannabinoid ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in their safety and cannabinoid-1 receptor (CB1R) pharmacology. As efficacy represents a critical parameter to understanding drug action, the present study investigated this metric by assessing in vivo and in vitro actions of THC, two well-characterized SCs (WIN55,212-2 and CP55,940), and three abused SCs (JWH-073, CP47,497, and A-834,735-D) in CB1 (+/+), (+/−), and (−/−) mice. All drugs produced maximal cannabimimetic in vivo effects (catalepsy, hypothermia, antinociception) in CB1 (+/+) mice, but these actions were essentially eliminated in CB1 (−/−) mice, indicating a CB1R mechanism of action. CB1R efficacy was inferred by comparing potencies between CB1 (+/+) and (+/−) mice [+/+ ED50 /+/− ED50], the latter of which has a 50% reduction of CB1Rs (i.e., decreased receptor reserve). Notably, CB1 (+/−) mice displayed profound rightward and downward shifts in the antinociception and hypothermia dose-response curves of low-efficacy compared with high-efficacy cannabinoids. In vitro efficacy, quantified using agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in spinal cord tissue, significantly correlated with the relative efficacies of antinociception (r = 0.87) and hypothermia (r = 0.94) in CB1 (+/−) mice relative to CB1 (+/+) mice. Conversely, drug potencies for cataleptic effects did not differ between these genotypes and did not correlate with the in vitro efficacy measure. These results suggest that evaluation of antinociception and hypothermia in CB1 transgenic mice offers a useful in vivo approach to determine CB1R selectivity and efficacy of emerging SCs, which shows strong congruence with in vitro efficacy.

Introduction

Synthetic cannabinoids (SCs), comprising diverse structures and largely unknown pharmacology (Kronstrand et al., 2013; Louis et al., 2014; Sobolevsky et al., 2015), have emerged as drugs of abuse and represent a significant public health concern (Law et al., 2015; Trecki et al., 2015). In contrast to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive constituent of cannabis, SCs have been linked to physiologic toxicity (Freeman et al., 2013; Takematsu et al., 2014), greater psychologic complications (Celofiga et al., 2014; Meijer et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2015), and death (Behonick et al., 2014; Gerostamoulos et al., 2015; Shanks et al., 2015; Westin et al., 2015). These clinical observations suggest that SCs pose a greater public safety threat than cannabis/THC. Efforts to predict and limit the clinical harm of SC toxicity would benefit from new methods to characterize the pharmacology of emerging compounds.

The pharmacologic mechanisms that underlie heightened risk for medical complications by SCs compared with cannabis/THC are unknown and may vary according to the particular SC under consideration. Two important dimensions of SC pharmacology are efficacy at the cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) and potential non-CB1R sites of action. Similar to THC, SCs bind and activate G-protein–coupled CB1Rs, which play an important role in mediating pharmacologic effects produced by marijuana and CB1R agonists (Rinaldi-Carmona et al., 1994; Zimmer et al., 1999; Huestis et al., 2001). Based largely on results from in vitro assays of agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding (Burkey et al., 1997a,b; Selley et al., 1996; Sim et al., 1996), however, THC is a low-efficacy CB1R agonist, whereas many SCs function as high-efficacy CB1R agonists (Wiley et al., 2013, 2015). Accordingly, heightened CB1R efficacy may contribute to the heightened risk for adverse effects of SCs; however, existing in vivo assays used to assess cannabinoid effects have poor resolution or slow throughput for distinguishing CB1R agonist efficacy. For example, although THC and the SC WIN55,212-2, respectively, possess low and high CB1R efficacy in stimulating [35S]GTPγS binding (Selley et al., 1996; Breivogel et al., 1998; Griffin et al., 1998), these drugs produce comparable maximal effects in commonly used assays (catalepsy, hypothermia, and antinociception) to assess the in vivo pharmacology of cannabinoids in mice (Fan et al., 1994).

The present study used a novel strategy for using CB1 (+/+), (+/−), and (−/−) mice to facilitate efficient and precise in vivo evaluation of SC selectivity for, and efficacy at, CB1Rs. Specifically, the effects of six cannabinoids and two noncannabinoid comparison drugs were examined in all three mouse genotypes using well-established in vivo assays sensitive to cannabimimetic activity (i.e., catalepsy, hypothermia, antinociception). We made two predictions. First, we predicted that drug selectivity at CB1Rs for antinociception, hypothermia, and catalepsy will be revealed by comparing effects in CB1 (+/+) and (−/−) mice, such that selective CB1R agonists will produce effects in CB1 (+/+) mice, but not in CB1 (−/−) mice. Second, we predicted that differences in drug efficacy at CB1Rs will be revealed by comparing dose-effect curves between CB1 (+/+) and (+/−) mice. CB1R density is 50% lower in CB1 (+/−) than in (+/+) mice (Selley et al., 2001) and decreases in receptor density produce greater rightward or downward shifts in dose-effect curves for low- than for high-efficacy agonists (Comer et al., 1992). Accordingly, we predicted that dose-effect curves will be shifted further rightward or downward for low- than high-efficacy cannabinoids in CB1 (+/−) relative to (+/+) mice. The drugs selected for study included THC, the well-characterized SCs CP55,940 and WIN55,212-2, two SCs associated with abuse CP47,497, JWH-073 (Atwood et al., 2011), and the heat degradant of the SC A-834,735 (Frost et al., 2010). Published (Griffin et al., 1998; Grim et al., 2016), and preliminary data suggest that these compounds display a range of CB1R efficacies as assessed in vitro by maximal stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding, such that low (e.g., THC), moderate (e.g., JWH-073, CP47,497), and high (e.g., CP55,940, WIN55,212-2, A-834,735D) degrees of CB1R efficacy are represented. The noncannabinoids morphine and chlorpromazine, which are active in subsets of these assays (Wiley and Martin, 2003), served as comparison drugs. Additionally, [3H]SR141716A binding was conducted to confirm a 50% decrease in CB1R density in (+/−) mice. Finally, the cannabinoids were evaluated for their efficacy to stimulate [35S]GTPγS binding in transgenic mouse tissue to provide an in vitro correlate of in vivo efficacy measures. The in vitro assays used cerebellar and spinal cord tissues, which represent central nervous system (CNS) regions expressing high and low CB1R density, respectively. Correlations between in vivo and in vitro measures of efficacy were used to identify optimal strategies for in vivo assessment of drug efficacy at CB1Rs.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Male and female CB1 (+/+), (+/−), and (−/−) mice (Zimmer et al., 1999) derived from CB1 (+/−) breeding pairs backcrossed at least 15 generations on a C57BL/6J background served as subjects. Mice had ad libitum access to food and water and were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. A total of 224 mice between 8 and 36 weeks of age were used for all experiments, which consisted of 192 mice in the in vivo experiments with 24 mice per drug, with n = 7–10 for each genotype, such that at least seven CB1R (+/+), seven (+/−), and seven (−/−) mice. Thirty-two mice for the in vitro studies in which cerebella and spinal cords were dissected from 12 (+/+), 12 (+/−), and 8 (−/−) mice. In all cases, at least three male and three female mice were included in each genotype, for each experiment. The experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drugs

Studies used THC and the following five SCs reported to have higher efficacy than THC at CB1Rs (in order from purported highest to lowest efficacy): A-834,735 degradant (A-834,735D), WIN55,212-2 and CP55,940, JWH-073, and CP47,497 (Breivogel et al., 1998; Griffin et al., 1998; Auwärter et al., 2009; Atwood et al., 2011; Thomas and Wiley, 2014; Grim et al., 2016).The μ opioid receptor agonist morphine and dopamine receptor antagonist chlorpromazine were tested as controls that were expected to produce in vivo effects independent of CB1R density. A-834,735D, WIN55,212-2, CP47,497, JWH-073, and chlorpromazine were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), and morphine, THC, and CP55,940 were generously supplied by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program. Each drug was administered in a vehicle consisting of ethanol, Emulphor EL-620, and 0.9% saline in a ratio of 1:1:18. For binding assays, THC-Certified Reference Material and CP55,940 (both in methanol) were acquired from Cayman, and [3H]SR141716A was purchased from Perkin-Elmer (Waltham, MA).

In Vivo Assays

To assess in vivo cannabimimetic activity, cumulative dose-response curves of each test compound in producing catalepsy, hypothermia, and antinociception were established, as previously described (Falenski et al., 2010). The bar test was used to assess catalepsy. In this assay, the mouse’s forepaws were placed on a metal bar 4.5 cm above the workspace, and immobility time (with the exception of movement related to respiration) was measured for a 60-second period. If the mouse removed its forepaws from the bar, they were placed back on the bar with a maximum of four occasions. In the event the mouse removed its forepaws from the bar for a fifth time, the test ended and the immobility time scored up to that time point was recorded. To assess antinociception, the distal 1 cm of the tail was immersed in a 52°C water bath, and the latency to remove the tail from the water was recorded. Rectal temperature was assessed by inserting a thermocouple probe (Physitemp Instruments, Clifton, NJ) 2 cm into the rectum. Completion of the three tests required approximately 10 minutes for a group of six mice. Thus, each group of mice was injected every 40 minutes with increasing doses of drug and tested 30 minutes after each injection. An injection volume of 10 μl/g was used for each dose, with the exception of doses in which the drug concentration exceeded solubility or suspension. In these cases, the final injection volumes were increased as follows: 16.6 μl/g for WIN55,212-2, 14.4 μl/g for CP55,940, 16.6 μl/g for JWH-073, and 13 μl/g for THC. The injection volumes to achieve the two highest doses of CP47,497 (56 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) were 13 μl/g and 22 μl/g, respectively. A-834,735D did not require additional volume for any of the injections.

Binding Assays

Membrane Preparation.

Male and female CB1 (+/+), (+/−), and (−/−) mice were euthanized via rapid decapitation. Cerebella were collected and hemisected, and whole spinal cords were removed as previously described (Nguyen et al., 2012). Tissue was stored at −80°C until assay. At the start of the binding assay, samples were placed in 5 ml of cold membrane buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4) and homogenized. The homogenates were centrifuged at 50,000g for 10 minutes, the supernatant was removed, and the samples were resuspended in assay buffer (100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4). For agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS experiments, membranes (8 µg/ml of protein) were incubated with adenosine deaminase (4 mU/ml) in assay buffer at 30°C for 12 minutes before addition to assay tubes.

[3H]SR141716A Binding.

Using established methods (Selley et al., 2001), cerebellum and spinal cord samples were diluted with assay buffer to 10 μg/ml and 15 μg/ml, respectively. Membrane homogenates were then incubated with [3H]SR141716A (0.03–10 nM) in the absence and presence of a saturating concentration of unlabeled SR141716A (5 μM) to assess specific and nonspecific binding. The assay was incubated until equilibrium was attained (90 minutes) at 30°C, and then the reaction was terminated by rapid filtration under vacuum through Whatman GF/B glass fiber filters presoaked in Tris buffer containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), followed by three washes with ice-cold Tris buffer. Bound radioactivity was measured via liquid scintillation spectrophotometry at 45% efficiency after a 9-hour delay.

Agonist-Stimulated [35S]GTPγS Binding.

Concentration-effect curves were generated by incubating varying concentrations of cannabinoid agonist with 30 μM guanosine diphosphate (GDP), 0.1 nM [35S]GTPγS, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin in duplicate and incubated at 30°C for 2 hours (Nguyen et al., 2012). Basal binding was determined in the absence of agonist, and nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 20 μM unlabeled GTPγS. The reaction was terminated by vacuum filtration through grade GF/B glass fiber filters, followed by two washes with cold Tris buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4). Bound radioactivity was assessed via liquid scintillation spectrophotometry at 95% efficiency after overnight extraction in scintillation fluid (Research Products International, Mount Prospect, IL). For agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding, nonspecific binding was subtracted from each drug curve, and data were expressed as percent stimulation ((stimulated-basal)/basal) × 100). As a small magnitude of stimulation was detected in CB1 (−/−) tissue in certain instances (e.g., WIN55,212-2) (Breivogel et al., 2001; Monory et al., 2002), the stimulation from (−/−) tissue was subtracted from CB1 (+/+) and (+/−) curves to provide an accurate representation of CB1R-mediated agonist-stimulated binding.

Data Analyses

The dose-effect curve of each drug on each in vivo endpoint was analyzed by two-way mixed design analysis of variance with dose (within subject) and genotype (between subjects) as the two factors. The Holm-Sidak post hoc test was used to assess dose-dependent changes within genotype as well as differences in drug effect among genotypes at each dose. In addition, ED50 values and 95% confidence limits for drug effects on behavioral measures were determined via linear regression (Colquhoun, 1971), and ED50 values were considered to differ if 95% confidence limits did not overlap. The ED50 value was defined as the dose to produce immobility for 30 seconds in the bar test for catalepsy, a 4°C loss in body temperature for hypothermia, and 50% of the maximum possible effect in the tail withdrawal test for antinociception. To assess changes in pharmacologic effects produced by reducing CB1R density [i.e., in CB1 (+/+) versus CB1 (+/−) mice] dose ratios were calculated using the equation (CB1 (+/+) ED50/CB1 (+/−) ED50) for each agonist on each in vivo measure. This dose ratio served as an in vivo measure of CB1R agonist efficacy.

For [3H]SR141716A radioligand binding assays, saturation binding (Bmax) and affinity (KD) were determined by nonlinear regression saturation analysis in GraphPad Prism 6.0 and was expressed as mean values ± standard error of the mean. Maximal stimulation (Emax) and EC50 values for agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding were determined via nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software. Significant differences between (+/+) and (+/−) Emax values were determined by Student’s t test for each drug. Differences in Emax across (+/+) samples in cerebellum and spinal cords were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by a Tukey post hoc test.

Pearson correlations were calculated between dose ratios [CB1 (+/+) ED50 / CB1 (+/−) ED50] from in vivo (catalepsy, hypothermia, and antinociception) measures and Emax ratios (CB1 (+/+) Emax/CB1 (+/−) Emax) from agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding assays in cerebellar and spinal cord tissue.

Results

In Vivo Effects of Cannabinoids in CB1R (+/+), (+/−), and (−/−) Mice.

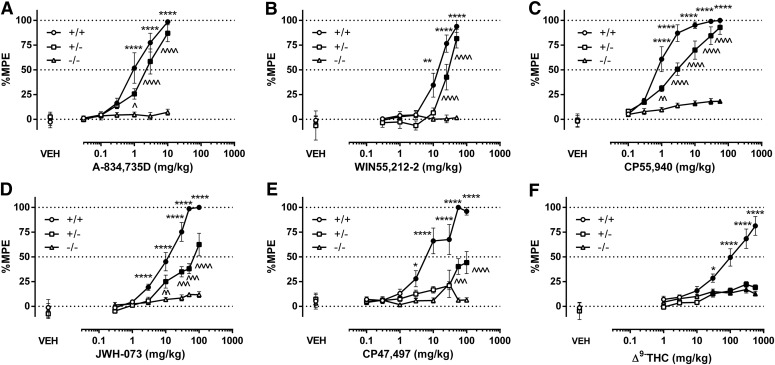

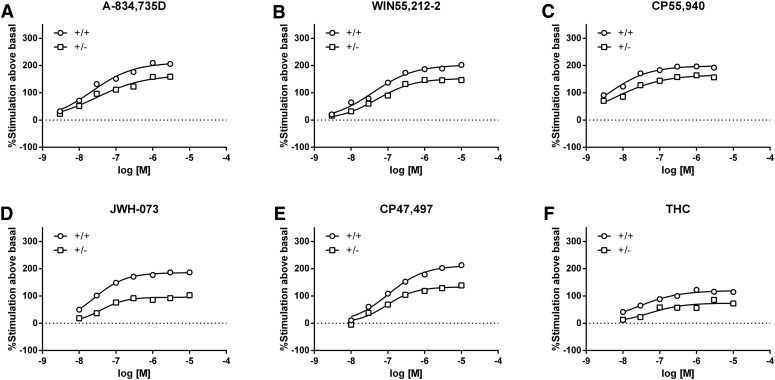

The cumulative dose-response evaluations of the six tested cannabinoids in CB1R transgenic mice revealed stratification for antinociceptive efficacy. A-834,735D (Fig. 1A), WIN55,212-2 (Fig. 1B), CP55,940 (Fig. 1C), JWH-073 (Fig. 1D), CP47,497 (Fig. 1E), and THC (Fig. 1F) produced significant dose-dependent antinociceptive effects in (+/+) mice, showed varying degrees of rightward shifts as well as decreased Emax values in (+/−) mice, and generally lacked activity in (−/−) mice (see Supplemental Table 1 for statistics and Supplemental Table 2 for baseline conditions). Dose ratios for each of the cannabinoids revealed dramatic decreases in potency in (+ /-) mice compared with (+/+) mice (Table 1). The maximum %MPE values for JWH-073, CP47,497, and THC were lower in (+/−) mice than in (+/+) mice. As the magnitude of effects of CP47,497 and THC did not surpass 50% and 25% MPE, respectively, neither the antinociceptive ED50 values in (+/−) mice nor the dose-ratios (CB1 (+/+)/CB1 (+/−) mice) were calculated. The diminished antinociceptive effects of all drugs in the (+/−) mice were revealed by parametric statistics (see Supplemental Table 1 and post hoc comparisons in Fig. 1). No consistent sex differences were observed for antinociception or the other measures (Supplemental Table 3). A single high dose of each drug produced antinociception from 0.5 to 6 hours in (+/+) mice, and (+/−) mice displayed decreased effects and shorter durations of action, although the actions of 100 mg/kg THC were greatly attenuated in both genotypes (Supplemental Figs. 1–6, Panel A for each figure).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of cannabinoid-induced antinociception between CB1 (+/−) and CB1 (+/+) mice reveals differential CB1R efficacy of cannabinoids. The high-efficacy agonists A-834,735D (A) potency ratio (PR) (95% CL) = 1.8 (1.1–3.1) and WIN55,212-2 (B) PR (95% CL) = 2.5 (1.4–5.0) produced relatively small rightward shifts in potencies in (+/−) mice compared with (+/+) mice. CP55,940 (C) PR (95% CL) = 3.5 (2.1–5.9) produced an increased rightward shift in the potency of CB1 (+/−) mice. JWH-073 (D), CP47,497 (E), and THC (F) failed to produce maximal effects in CB1 (+/−) mice, which precluded the accurate calculation of potency ratios. None of the drugs produced appreciable antinociceptive effects in CB1 (−/−) mice. The mean ± S.E.M. baseline tail withdrawal latency for all groups was 2.05 ± 0.05 seconds. VEH indicates an injection of 1:1:18 vehicle before cumulative dosing with the indicated drug. Filled shapes indicate P < 0.05 CB1 (+/+) and (+/−) versus CB1 (−/−) controls; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 (+/+) versus CB1 (+/−) mice, n = 7–10 mice per genotype per drug.

TABLE 1.

Calculated ED50 and dose ratio values for antinociception, hypothermia, and catalepsy in CB1 (+/+) and (+/−) mice

Each cannabinoid produced significantly more potent antinociceptive and hypothermic effects in CB1 (+/+) mice than in CB1 (+/−) mice, with the exception of WIN55,212-2-induced antinociception, which did not significantly differ between genotypes. Each respect ligand showed equal potency between (+/+) and (+/−) mice for the catalepsy measure. ED50 values are expressed in mg/kg. Dose ratios were calculated for each drug by dividing the CB1 (+/+) ED50 by the CB1 (+/−) ED50. In cases in which the maximal effects of a drug failed to exceed a 50% effect, the Emax is presented.

| (+/+) ED50 (95% CL) | (+/−) ED50 (95% CL) | Dose Ratio (+/−)/(+/+) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antinociception A-834,735D | 0.85 (0.61–1.19) | 1.84 (1.66–2.04)* | 2.17 |

| WIN55,212-2 | 9.64 (6.44–14.41) | 33.76 (14.96–76.19)* | 3.57 |

| CP55,940 | 0.83 (0.67–1.03) | 2.71 (1.95–3.78)* | 3.33 |

| JWH-073 | 7.84 (5.84–10.52) | 96.58 (47.41-196.76)* | 12.50 |

| CP47,497 | 5.09 (3.39–7.64) | 100 mg/kg: 44.3 ± 11.2% MPE | <20 |

| THC | 81.69 (51.32–130.03) | 560 mg/kg: 19.2 ± 2.7% MPE | <6.67 |

| Hypothermia | |||

| A-834,735D | 0.85 (0.67–1.00) | 1.64 (1.59–1.69)* | 1.92 |

| WIN55,212-2 | 7.27 (5.54–9.55) | 15.68 (9.95–24.72)* | 2.17 |

| CP55,940 | 0.78 (0.62–0.98) | 2.27 (1.85–2.79)* | 2.94 |

| JWH-073 | 8.75 (6.99–10.94) | 31.16 (21.08–46.06)* | 3.57 |

| CP47,497 | 10.92 (8.63–13.82) | 41.45 (32.77–52.44)* | 4.76 |

| THC | 155.67 (120.63–200.88) | 560 mg/kg: −2.75 ± 0.57°C* | <3.57 |

| Catalepsy | |||

| A-834,735D | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) | 0.94 (0.73–1.21) | 1.15 |

| WIN55,212-2 | 3.82 (2.79–5.22) | 5.79 (4.11–8.16) | 1.41 |

| CP55,940 | 0.38 (0.27–54) | 0.58 (0.46–0.75) | 1.54 |

| JWH-073 | 7.72 (5.97–9.99) | 8.03 (6.01–10.73) | 1.04 |

| CP47,497 | 5.91 (3.78–9.26) | 5.17 (3.40–7.87) | 0.88 |

| THC | 28.36 (17.99–44.72) | 49.27 (36.35–66.78) | 1.72 |

Indicates non-overlapping confidence intervals between (+/+) and (+/−) ED50 values.

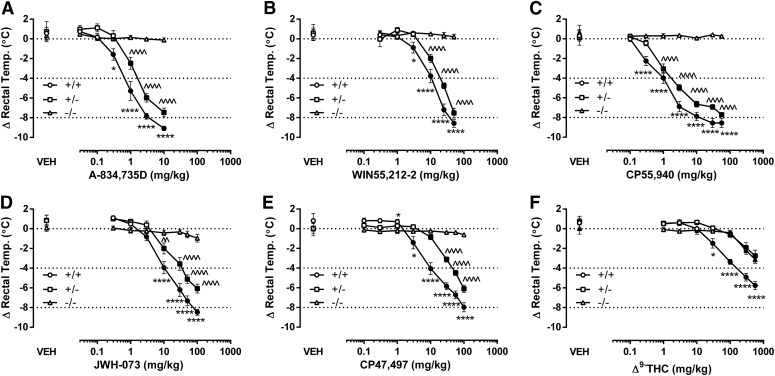

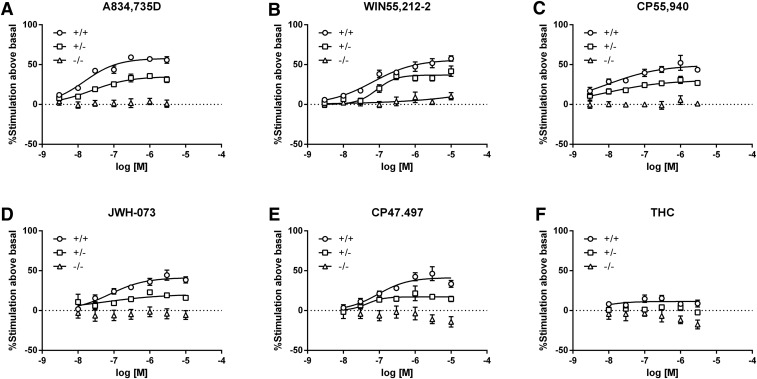

A-834,735D (Fig. 2A), WIN55,212-2 (Fig. 2B), CP55,940 (Fig. 2C), JWH-073 (Fig. 2D), CP47,497 (Fig. 2E), and THC (Fig. 2F) produced hypothermic effects in the same rank order as antinociception. Each compound produced dose-dependent hypothermia in (+/+) and (+/−) mice but did not substantially affect rectal temperatures in (−/−) mice, with the exception of high doses of THC (300 and 560 mg/kg). These doses of THC significantly lowered rectal temperature in (+/−) and (−/−) mice but were substantially less in magnitude than found in (+/+) mice (see Supplemental Table 1 for statistics and Supplemental Table 2 for baseline values). Each drug was more potent in (+/+) mice than in (+/−) mice (Table 1). The decreased magnitude of hypothermia in (+/−) mice, which did not exceed the 4°C drop required for calculation, precluded the calculation of the ED50 values as well as the dose ratios (CB1 (+/+)/ CB1 (+/−) mice); however, the diminished hypothermic effects in the (+/−) mice compared with (+/+) mice were revealed by parametric statistics (see Supplemental Table 1) with appropriate post hoc analyses (Fig. 2). The time-course studies showed that each cannabinoid reduced body temperature from 0.5 to 6 hours (Supplemental Figs. 1-6, Panel B for each figure).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of cannabinoid-induced hypothermia between CB1 (+/−) and CB1 (+/+) mice reveals differential CB1R efficacy of cannabinoids. A-834,735D (A) PR (95% CL) = 1.8 (1.4–2.3); WIN55,212-2 (B), PR (95% CL) = 1.8 (1.3–2.4); and CP55,940 (C) PR (95% CL) = 2.0 (1.5–2.8) produced approximately 2-fold rightward shifts in the dose-response relationship for CB1 (+/−) mice. JWH-073 (D) PR (95% CL) = 2.7 (2.0–3.8); and CP47,497 (E) PR (95% CL) = 3.6 (2.7–4.7) produced further magnitudes in rightward dose-response shifts in the CB1 (+/−) mice. In contrast, THC-induced hypothermia (F) showed an apparent loss of efficacy in CB1 (+/−) mice, with CB1 (+/−) and (−/−) mice showing identical drops in body temperature (−2.9 ± 0.5 C and −2.8 ± 0.4°C, respectively) at 560 mg/kg THC. None of the other drugs significantly reduced body temperature in CB1 (−/−) mice. The preinjection mean ± S.E.M. rectal temperature for all groups was 36.7 ± 0.05°C. Data are expressed as change from baseline. VEH indicates an injection of 1:1:18 vehicle before cumulative dosing with the indicated drug. Filled shapes indicate P < 0.05 CB1 (+/+) and (+/−) versus CB1 (−/−) mice. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 (+/+) versus CB1 (+/−) mice; n = 7–10 mice per genotype per drug.

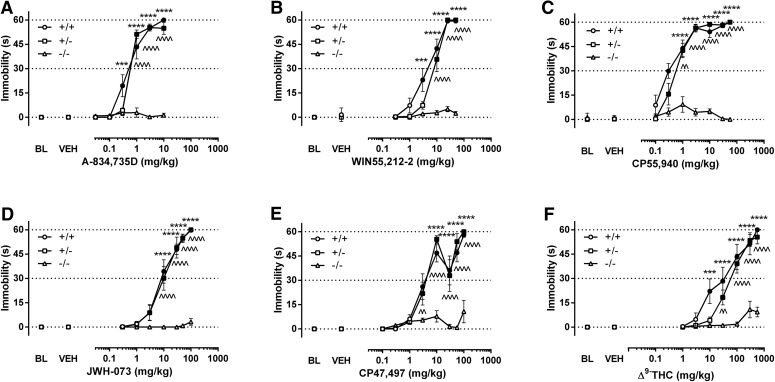

In contrast to antinociception and hypothermia, the catalepsy dose-response relationship of each drug was minimally affected by a 50% reduction in CB1R. Each cannabinoid yielded comparable dose-response relationships between (+/+) and (+/−) mice but was inactive in (−/−) mice for A-834,735D (Fig. 3A), WIN55,212-2 (Fig. 3B), CP55,940 (Fig. 3C), JWH-073 (Fig. 3D), CP47,497 (Fig. 3E), and THC (Fig. 3F). The statistical analyses and baseline conditions are shown in Supplemental Table 1 and 2, respectively. The time course of each drug in producing catalepsy is shown in Supplemental Figs. 1–6 (Panel C for each figure).

Fig. 3.

CB1 (+/−) mice displayed minimal differences in potency from their (+/+) counterparts for each drug in the catalepsy measure. Cannabinoid-induced catalepsy between CB1 (+/+) and (+/−) mice was virtually identical for A-834.735D (A) PR (95% CL) = 1.1 (0.88–1.48)), WIN55,212-2 (B) PR (95% CL) = 1.42 (1.03–1.95); CP55,940 (B) PR (95% CL) = 1.39 (0.89–2.20), JWH-073 (D) PR (95% CL) = 1.04 (0.72–1.49), CP47,497 (E) PR (95% CL) = 1.14 (0.44-3.02)), and THC (D); PR (95% CL) = 1.75 (1.01–2.93)). None of the drugs produced significant cataleptic effects in (−/−) mice. Filled symbols indicate P < 0.05 versus respective vehicle for each genotype; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 (+/+) versus (−/−); ^P < 0.05; ^^P < 0.01; ^^^P < 0.001; ^^^^P < 0.0001 (+/−) versus (−/−), n = 7–10 mice per genotype per drug.

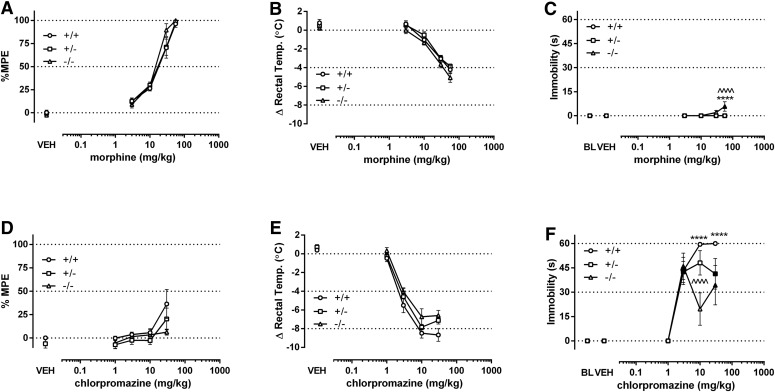

In the final in vivo experiment, we examined dose-response relationships of two noncannabinoid drugs, morphine and chlorpromazine, as well as repeated vehicle injections in CB1R transgenic mice. Altering CB1R number did not affect the pharmacologic effects of either drug in a systematic manner. The dose-response relationships of morphine for antinociception (Fig. 4A) and hypothermia (Fig. 4B) were not significantly affected by genotype (Supplemental Table 1). Morphine produced a significant statistical interaction for immobility in the bar test, which was due to a relatively small increase of immobility in CB1 (−/−) mice compared with the other genotypes (Fig. 4C). Chlorpromazine did not significantly stimulate antinociception in any of genotypes (Fig. 4D), and its hypothermic effects were equipotent in (+/+), (+/−), and (−/−) mice (Fig. 4E; Supplemental Table 1). The cataleptic effects of chlorpromazine differed statistically among genotypes (Fig. 4F; Supplemental Table 1), but no differences in potency were found as determined by linear regression. As previously reported (Falenski et al., 2010), repeated vehicle injections were generally without effect in each genotype; although CB1 (−/−) mice displayed increased immobility after the fifth injection (Supplemental Fig. 7).

Fig. 4.

Use of CB1R transgenic mice demonstrates that noncannabinoid drugs produce nonselective pharmacologic effects in CB1 (+/+), (+/−), and (−/−) mice. Morphine produced dose-dependent antinociceptive (A) and hypothermic (B) effects irrespective of genotype. However, morphine did not produce substantial effects on catalepsy other than a small, but significant, effect in (−/−) mice (C). Chlorpromazine produced minimal antinociceptive effects, but was unaffected by genotype (D). In contrast, chlorpromazine dose dependently decreased body temperature (E) and increased catalepsy (F) regardless of genotype. ****P < 0.0001 versus wild type and HET, n = 7–9. Filled shapes indicate P < 0.05 versus respective vehicle for each genotype; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 (+/+) versus (−/−); ^P < 0.05, ^^P < 0.01; ^^^P < 0.001; ^^^^P < 0.0001 (+/−) versus (−/−); n = 7–10 mice per genotype per drug.

[3H]SR141716A and Agonist-Stimulated [35S]GTPγS Binding in CB1R (+/+), (+/−), and (−/−) Mice.

[3H]SR141716A binding was used to determine the density of CB1Rs in cerebellum and spinal cord (Table 2). CB1R levels in the cerebellum were approximately 4-fold higher than levels measured in the spinal cord. Accordingly, cerebellum was considered a high CB1R expression region, and spinal cord was defined as a low CB1R expression region. Consistent with previous reports (Selley et al., 2001), the level of CB1Rs in (+/−) mice was approximately half the number of receptors in (+/+) mice for both regions.

TABLE 2.

[3H]SR141716A radioligand binding in cerebellar and spinal cord membranes from CB1 (+/+) and (+/−) mice

CB1 (+/−) mice express half the number of CB1Rs as CB1 (+/+) mice in cerebellar and spinal cord tissue. The KD value of [3H]SR141716A did not differ between genotypes or across central nervous system regions (P = 0.40).

| Cerebellum |

Spinal Cord |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bmax (pmol/mg) | KD [nM] | Bmax (pmol/mg) | KD [nM] | |

| CB1 (+/+) | 4.32 ± 0.30 | 1.15 ± 0.14 | 0.97 ± 0.09 | 0.58 ± 0.12 |

| CB1 (+/−) | 1.89 ± 0.36*** | 0.95 ± 0.21 | 0.58 ± 0.10# | 0.90 ± 0.34 |

P < 0.001 (+/+) versus (+/−) Bmax in cerebellum; #P < 0.05 (+/+) versus (+/−) Bmax in spinal cord, n = 8 for each genotype per tissue.

Each cannabinoid agonist was then assessed using [35S]GTPγS binding in membrane homogenates from the cerebellum and spinal cord of CB1 (+/+), (+/−), and (−/−) mice. As previously reported (Breivogel et al., 2001; Monory et al., 2002), WIN55,212-2 significantly stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in cerebellar homogenates from CB1 (−/−) mice (Supplemental Fig. 8, Supplemental Table 4). None of the other ligands stimulated G-protein activity in cerebellar homogenates from CB1 (−/−) mice. To eliminate non-CB1R–mediated stimulation from (+/+) and (+/−) binding dose-effect curves, the magnitude of stimulation in the CB1 (−/−) tissue was subtracted from the total stimulation in tissue from the (+/+) and (+/−) mice (Fig. 5). The Emax values of A-834,735D [T (6) = 2.54, P < 0.05], WIN55,212-2 [T (6) = 5.48, P < 0.01], CP55,940 [T (6) = 3.47, P < 0.05], JWH-073 [T (6) = 21.0, P < 0.0001], CP47,497 [T (6) = 6.84, P < 0.001], and THC [T (6) = 4.44, P < 0.01] were significantly reduced in cerebellar membranes prepared from CB1 (+/−) compared with (+/+) mice (Table 3, top). Moreover, the THC Emax value in cerebellum from (+/+) mice was significantly lower than the Emax value of each of the other ligands [F (5,18) = 23.14, P < 0.0001]. In (+/−) cerebellum, the Emax of JWH-073 differed significantly from that of A-834,735D, WIN55,212-2, and CP55,940 [F (5,18) = 15.26, P < 0.0001]. Likewise, Emax values from spinal cord membranes were significantly lower in CB1 (+/−) mice than in (+/+) mice for A-834,735D [T (6) = 5.82, P < 0.01], WIN55,212-2 [T (6) = 4.28, P < 0.01], CP55,940 [T (6) = 2.60, P < 0.05], and CP47,497 [T (6) = 5.33, P < 0.01] (Table 3, middle; Fig. 6). Although the Emax values of JWH-073 (P = 0.052) and THC (P = 0.11) in spinal cord from CB1 (+/−) and (+/+) mice did not significantly differ, THC did not stimulate [35S]GTPγS binding above basal levels in spinal cords from CB1 (+/−) mice. Statistical comparison of Emax values from (+/−) spinal cord tissue revealed significant differences between JWH-073 and both WIN55,212-2 and A-834,735D, whereas CP47,497 differed only from WIN55,212-2 [F (4, 13) = 6.00, P < 0.01]. Finally, THC [F (5, 18) = 15.26, P < 0.0001] produced significantly less stimulation than each other ligand in the spinal cords of (+/+) mice.

Fig. 5.

Agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding under high CB1R density conditions (i.e., cerebellum) from CB1 transgenic mice reveals equal levels of maximal stimulation for each synthetic agonist tested. A-834,735D (A), WIN55,212-2 (B), CP55,940 (C), JWH-073 (D), and CP47,497 (E) displayed maximal stimulation of CB1R in (+/+) cerebella (approximately 200% above basal), whereas THC (F) activation was markedly reduced (106% ± 6.2% above basal) relative to the SCs. In cerebellar membranes from CB1 (+/−) mice, the high efficacy SCs A-834,735D, WIN55,212-2, and CP55,940 stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding to approximately 80% of observed (+/+) maximums, whereas JWH-073, CP47,497, and THC each elicited about 50% of the response of (+/+) membranes. A summary of Emax and EC50 values in cerebellar tissue from CB1 (+/+) and (+/−) mice is shown in Table 3, top. Because WIN55,212-2 elicited significant binding above basal activity in CB1 (−/−) tissue (Supplemental Fig. 8), this non-CB1R stimulation was subtracted from dose-response curves in tissue from CB1 (+/+) and (+/−) mice to represent CB1R activation. n = 4 mice per genotype.

TABLE 3.

Calculated Emax and EC50 values from agonist-stimulated GTPgS binding experiments in CB1 (+/+) and (+/−) membranes from cerebellum and spinal cord tissue

| Agonist | CB1 (+/+) |

CB1 (+/−) |

(+/−) Emax/(+/+) Emax | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emax | EC50 | Emax | EC50 | ||

| Cerebelluma | |||||

| A-834,735D | 211.1 ± 11.4 | 22.3 ± 5.6 | 164.9 ± 14.1*# | 29.4 ± 11.9 | 0.78 |

| WIN55,212-2 | 202.5 ± 7.6 | 39.4 ± 7.6 | 152.6 ± 4.9**# | 50.4 ± 8.0 | 0.75 |

| CP55,940 | 198.7 ± 5.2 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 166.3 ± 7.6*# | 6.1 ± 1.4 | 0.84 |

| JWH-073 | 185.5 ± 1.7 | 25.6 ± 1.2 | 95.5 ± 3.9**** | 38.3 ± 7.1 | 0.51 |

| CP47,497 | 212 ± 8.6 | 102.1 ± 18.2 | 133.3 ± 7.6*** | 94.5 ± 22.8 | 0.63 |

| THC | 119.9 ± 4.6^ | 24.3 ± 4.7 | 73.8 ± 8.7**^ | 52.4 ± 29.0 | 0.62 |

| Spinal cordb | |||||

| A-834,735D | 57.8 ± 2.4 | 15.0 ± 3.0 | 35.0 ± 3.0** | 24.1 ± 9.6 | 0.61 |

| WIN55,212-2 | 56.3 ± 3.8 | 65.4 ± 22.0 | 36.9 ± 2.4** | 84.8 ± 21.6 | 0.66 |

| CP55,940 | 49.6 ± 5.9 | 8.61 ± 5.1 | 30.4 ± 4.3* | 9.5 ± 6.9 | 0.61 |

| JWH-073 | 41.3 ± 3.5 | 77.8 ± 29.9 | 20.6 ± 7.7# | 46.6 ± 91.0 | 0.49 |

| CP47,497 | 41.2 ± 3.9 | 93.2 ± 38.1 | 17.1 ± 2.2**#$ | 45.9 ± 24.2 | 0.42 |

| THC | 11.4 ± 2.3^ | 6.1 ± 11.2 | ND | ND | ND |

ND, not determined; ^indicates significant differences versus all other ligands within (+/+) Emax values. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 for (+/+) versus (+/−) samples within tissue. ^P < 0.05 for THC versus other wild-type Emax values. #P < 0.05 for JWH-073 versus other (+/−) Emax values. $P < 0.05 for CP47,497 versus other (+/−) Emax values. No significant differences in EC50 were detected across brain region or genotype for each drug.

In cerebellum, all agonists elicited significantly lower [35S]GTPγS binding in (+/−) membranes than in (+/+) membranes. Comparison of CB1 (+/+) Emax values across drugs revealed that THC elicited the least stimulation of all ligands tested in (+/+) and (+/−) tissue.

Spinal cord membranes showed a similar pattern of results in which stimulation was significantly reduced in tissue from (+/−) mice compared with (+/+) mice, although the Emax value of JWH073 in CB1 (+/−) mice did not statistically differ from its Emax value in CB1 (+/+) mice (P = 0.052). The lack of detectable stimulation by THC in spinal cord tissue from CB1 (+/−) mice precluded the calculation of the Emax and EC50 values of this compound, although the moderate efficacy agonists CP47,497 and JWH-073 differed from WIN,55,212-2 in (+/−) spinal cord. In CB1 (+/+) spinal cord tissue, the Emax value of THC was significantly reduced compared with each of the other ligands. This loss of efficacy is expressed additionally as the CB1 (+/−) Emax/ CB1 (+/+) Emax to show relative differences between high receptor conditions of cerebellum and low receptor conditions of spinal cord.

Fig. 6.

Agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding under low CB1R density conditions (i.e., spinal cord tissue) from CB1 transgenic mice reveals differences in agonist efficacy. A-834,735D (A), WIN55,212-2 (B), CP55,940 (C), JWH-073 (D), and CP47,497 (E) stimulated binding to 40%–50% above basal in spinal cord tissue from CB1 (+/+) mice, with approximately half of the stimulation observed in spinal cords from CB1 (+/−) mice (20%–30% above basal. THC (F) activation of CB1R was attenuated in spinal cords from CB1 (+/+) mice (11.41 ± 2.3) and did not elicit any measurable stimulation of binding in membranes from CB1 (+/−) mice. A summary of Emax and EC50 values in spinal cord tissue from CB1 (−/−), (+/+) and (+/−) is shown in Table 3, middle rows. Significant stimulation above basal was not observed for any drugs in samples from CB1 (−/−) mice; therefore, values from all three genotypes are shown; n = 4 mice per genotype.

CB1R Agonist Efficacy: Relationship between In Vivo and In Vitro Measures.

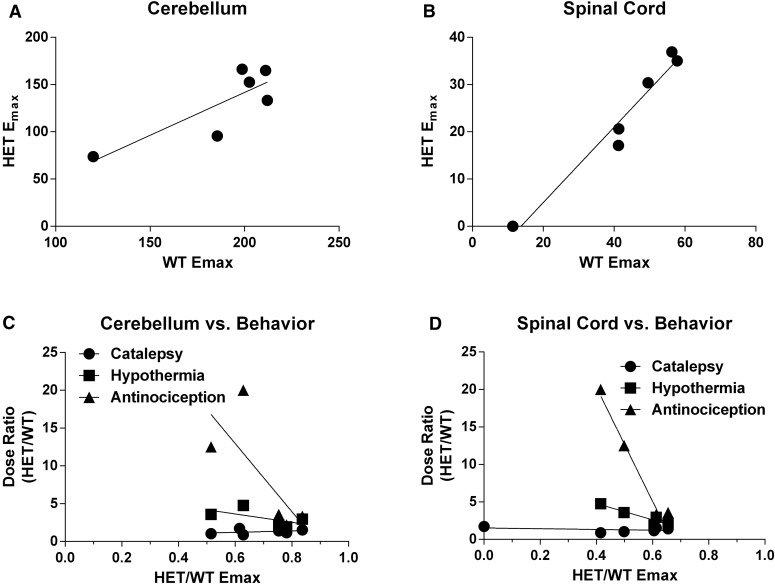

The relationships between in vivo dose ratios [CB1 (+/−) ED50/CB1 (+/+) ED50) for each of the three dependent variables and in vitro (+/+) Emax values from [35S]GTPγS binding assays (CB1 (+/−) Emax/CB1 (+/+) Emax) in cerebellum and spinal cord membranes are depicted in (Fig. 7). CB1 (+/−) and (+/+) binding correlated between cerebellum and spinal cord. The in vivo dose ratios for antinociception (r = 0.87) and hypothermia (r = 0.94), but not catalepsy, significantly correlated with [35S]GTPγS binding in spinal cord. No significant correlation was found between any of the in vivo measures and [35S]GTPγS binding in cerebellum. The structures for all agonists used in these studies can be seen in Supplemental Fig. 9.

Fig. 7.

Relationship between in vivo potency differences between (+/+) and (+/−) mice and in vitro Emax values from agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding experiments. In both cerebellum (A) and spinal cord (B), (+/+) Emax correlated with (+/−) Emax, demonstrating that the reduction in receptor population results in a concomitant reduction in the Emax magnitude. Cerebellum Emax ratios (+/− Emax / +/+ Emax) values did not correlate with catalepsy, hypothermia, or antinociception (C); however, spinal cord (+/+) Emax values highly correlated with losses of in vivo potency between (+/+) and (+/−) mice for both antinociception (r = 0.94; P < 0.01) and hypothermia (r = 0.87; P < 0.05) (D). The low magnitudes of antinociceptive and hypothermic effects produced by THC in the (+/−) mice precluded the calculation of dose ratios and inclusion in the correlation analysis.

Discussion

Receptor theory predicts that in vivo pharmacologic efficacy differences will be most apparent for pharmacologic effects mediated by CNS regions containing low receptor reserve and least evident for effects mediated by high receptor reserve (Rang, 2006). The results presented here apply this theory to CB1R-mediated pharmacologic effects. Through the use of: 1) a cumulative dose-response procedure and 2) CB1 transgenic mice that express varying densities of CB1Rs, we established a straightforward in vivo method to discern relative differences in agonist selectivity for, and efficacy at, CB1Rs. Specifically, we tested the impact of reducing total CB1R density on in vivo potency and efficacy of THC, five SCs, and two noncannabinoids, as well as the relationship between a metric of in vivo efficacy and in vitro functional activity.

Of the three in vivo dependent measures, antinociception was the most sensitive to a 50% reduction in CB1R density. CB1 (+/−) mice showed substantial reductions in antinociceptive potency and “apparent” efficacy to each cannabinoid compared with (+/+) mice. A-834,735D, WIN55,212-2, and CP55,940 produced maximal antinociceptive effects in (+/+) and (+/−) mice, but CB1 (+/−) mice displayed 2-fold decreases in potency to A-834,735D, and WIN55,212-2 and ∼3-fold decrease in potency to CP55,940. THC was the least potent cannabinoid in producing antinociception in (+/+) mice and produced less than 25% MPE in CB1 (+/−) mice. Similarly, JWH-073 and CP47,497, within the dose ranges tested, produced significantly reduced magnitudes of maximal antinociceptive effects in (+/−) mice compared with (+/+) mice. None of the tested cannabinoids produced significant antinociceptive effects in CB1 (−/−) mice. In contrast, morphine produced full antinociceptive effects irrespective of genotype, demonstrating selectivity of this in vivo model. This pattern of findings suggests relatively low CB1R reserve for cannabinoid-induced antinociception, which is consistent with the observation that CB1R density is relatively low in CNS areas (e.g., periaqueductal gray, dorsal horn of the spinal cord) (Herkenham et al., 1990, 1991; Matsuda et al., 1990) purported to mediate antinociception. Moreover, comparison of the dose-response relationship for each cannabinoid ligand between (+/+) and (+/−) mice revealed that THC, CP47,497, and JWH-073 behaved as low-efficacy CB1R agonists, CP55,940 had moderate efficacy, and A-834,735D and WIN55,212-2 were the highest efficacy compounds. This pattern of findings is in agreement with in vitro [35S]GTPγS binding experiments.

The dose-response curve for each agonist in producing hypothermia showed a rightward shift in CB1 (+/−) mice compared with (+/+) mice. Interestingly, the Emax of THC-induced hypothermia was profoundly reduced in CB1 (+/−) mice. The observation that the magnitude of hypothermia produced by 300 and 560 mg/kg THC did not statistically differ between (+/−) and (−/−) mice suggests CB1R-independent effects. In contrast, none of the other cannabinoids, at the doses assessed, produced hypothermia in CB1 (−/−) mice. Morphine and chlorpromazine elicited dose-dependent hypothermia irrespective of genotype, supporting the utility of using CB1R transgenic mice to infer selectivity. These findings, taken together with the low level of CB1R expression in the preoptic area of the hypothalamus (Herkenham et al., 1990), a region believed to mediate cannabinoid-induced hypothermia (Rawls et al., 2002), suggest relatively low CB1R reserve for this effect.

In contrast to the antinociceptive and hypothermic measures, the dose-response relationships of the cataleptic effects of each cannabinoid tested did not statistically differ between (+/+) and (+/−) mice, suggesting a relatively high CB1R reserve in brain regions that mediate catalepsy. Chlorpromazine produced catalepsy in all three genotypes, again indicating the utility of the assay to discern CB1R selectivity. The minimal rightward shift in the dose-response relationship of cannabinoids in CB1 (+/−) mice is consistent with high levels of CB1R expression in brain areas mediating catalepsy, including the dorsal striatum (∼3 or 4 pmol/mg), cerebellum (4–6 pmol/mg), and globus pallidus (≥6 pmol/mg), which represent among the highest levels in brain (Selley et al., 2001). Work from Dhawan et al. (2006) also suggests that cannabinoid-induced catalepsy requires low CB1R occupancy. Accordingly, a 50% reduction in CB1R expression appears insufficient to decrease potency and Emax catalepsy values of low efficacy CB1R agonists. Although these findings confirm that CB1Rs mediate cannabinoid-induced catalepsy, this dependent measure does not distinguish CB1R agonist efficacy and may suggest a high receptor reserve for this effect; however, the observations that cannabinoid agonists were not more potent in producing catalepsy compared with antinociception or hypothermia in CB1 (+/+) mice are inconsistent with the predicted results based upon receptor reserve. A limitation of determining potency in the in vivo dependent measures is the placement of arbitrary maximums that may not reflect true maximum effects.

Data from agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding experiments in spinal cord generally corroborated the a priori selection of CB1R agonists, which varied from high to low efficacy (A-834,735D ≥ WIN55,212-2 > CP55,940 > JWH-073 ≥ CP47,497 > THC), when relative Emax differences of (+/+) and (+/−) mice were taken into account. Significant correlations detected between Emax ratios from [35S]GTPγS binding in spinal cord and the in vivo hypothermia and antinociception measures were consistent with hypothesis that these effects were mediated by low CB1R reserve. Conversely, the absence of a correlation between catalepsy and receptor-mediated G-protein activation is consistent with the idea of high CB1R reserve. In the present study, we selected to investigate agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in cerebellum and spinal cord because these CNS regions are subserved respectively by high and low CB1R reserve. Thus, it will be important in future studies to examine CB1Rs in other brain regions that subserve relevant pharmacologic effects of cannabinoids in models of learning and memory, pain, reward, drug dependence, feeding, and stress responses. Future studies may focus on investigating where novel, abused SCs fall along the efficacy continuum. Although not currently available, irreversible CB1R antagonists would offer great utility to investigate the consequences of pharmacologically reducing CB1R density on relevant endpoints. This approach has been implemented successfully for the μ opioid receptor (Walker et al., 1998; Pawar et al., 2007; Madia et al., 2009).

In conclusion, the present study establishes a straightforward in vivo approach, based on pharmacologic principles, to provide valuable insight into the pharmacology of THC and emerging abused SCs. Here, we used CB1 (+/+), (+/−), and (−/−) mice to assess in vivo efficacy, potency, and selectivity of six cannabinoids and two noncannabinoids by assessing their pharmacologic effects in established assays sensitive to CB1R agonists. In particular, the high correlations between efficacy in stimulating [35S]GTPγS binding in spinal cord and producing antinociception and hypothermia in CB1 (+/−) mice suggests that these endpoints represent useful predictors of in vivo efficacy. Specifically, we found using in vivo and in vitro assays that THC, CP47,497, and JWH-073 acted as low efficacy CB1R agonists, whereas A-834,735D, WIN55,212-2, and CP55,940 behaved as high efficacy CB1R agonists. More generally, our results support the idea that low CB1R reserve mediates cannabinoid-induced antinociception and hypothermia, whereas CNS regions with high CB1R reserve may subserve cannabinoid-induced catalepsy. Thus, the use of CB1R transgenic mice to assess the antinociceptive and hypothermic effects of CB1R agonists in vivo along with agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in CB1R mouse spinal cord tissue in vitro possesses utility in determining the efficacy of emerging abused SCs. This model may also be extended to assess cannabinergic effects of novel therapeutic CB1R agonists and to determine whether efficacy represents an important determinant of the severe health complications associated with SC abuse compared with THC/cannabis. In sum, the results of the present study suggest that low receptor reserve conditions reveal stratification of CB1R ligands by efficacy and further bridge the gap of knowledge between in vivo and in vitro pharmacologic actions of CB1R agonists.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brittany Mason, Mohammed Mustafa, Pamela Weller, and Jolene Windle for assistance with breeding most of the mice used for these studies and the National Institute on Drug Abuse for the contribution of drugs used for these studies.

Abbreviations

- A-834,735 degradant

3,3,4-trimethyl-1-(1-((tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)methyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)pent-4-en-1-one

- CB1R

cannabinoid 1 receptor

- CNS

central nervous system

- CP47,497

rel-5-(1,1-dimethylheptyl)-2-[(1R,3S)-3-hydroxycyclohexyl]-phenol

- CP55,9440

5-(1,1-dimethylheptyl)-2-[(1R,2R,5R)-5-hydroxy-2-(3-hydroxypropyl)cyclohexyl]-phenol

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetra-acetic acid

- JWH-073

(1-butyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-1-naphthalenyl-methanone; chlorpromazine

- SC

synthetic cannabinoid

- THC

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- WIN55,212-2

(R)-(+)-[2,3-dihydro-5-methyl-3-(4-morpholinylmethyl)pyrrolo[1,2,3-de]-1,4-benzoxazin-6-yl]-1-napthalenylmethanone

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Grim, Morales, Gonek, Wiley, Thomas, Sim-Selley, Selley, Negus, Lichtman.

Conducted experiments: Grim, Morales, Gonek, Sim-Selley.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Endres, Sim-Selley, Selley.

Performed data analysis: Grim, Morales, Gonek, Selley, Negus, Lichtman.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Grim, Morales, Wiley, Thomas, Sim-Selley, Selley, Negus, Lichtman.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants T32DA007027, R01DA032933, R01DA03672, R01DA030404, and P30DA033934].

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Atwood BK, Lee D, Straiker A, Widlanski TS, Mackie K. (2011) CP47,497-C8 and JWH073, commonly found in ‘spice’ herbal blends, are potent and efficacious CB(1) cannabinoid receptor agonists. Eur J Pharmacol 659:139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auwärter V, Dresen S, Weinmann W, Müller M, Pütz M, Ferreirós N. (2009) ‘Spice’ and other herbal blends: harmless incense or cannabinoid designer drugs? J Mass Spectrom 44:832–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behonick G, Shanks KG, Firchau DJ, Mathur G, Lynch CF, Nashelsky M, Jaskierny DJ, Meroueh C. (2014) Four postmortem case reports with quantitative detection of the synthetic cannabinoid, 5F-PB-22. J Anal Toxicol 38:559–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivogel CS, Griffin G, Di Marzo V, Martin BR. (2001) Evidence for a new G protein-coupled cannabinoid receptor in mouse brain. Mol Pharmacol 60:155–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivogel CS, Selley DE, Childers SR. (1998) Cannabinoid receptor agonist efficacy for stimulating [35S]GTPgammaS binding to rat cerebellar membranes correlates with agonist-induced decreases in GDP affinity. J Biol Chem 273:16865–16873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkey TH, Quock RM, Consroe P, Ehlert FJ, Hosohata Y, Roeske WR, Yamamura HI. (1997a) Relative efficacies of cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonists in the mouse brain. Eur J Pharmacol 336:295–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkey TH, Quock RM, Consroe P, Roeske WR, Yamamura HI. (1997b) delta 9-Tetrahydrocannabinol is a partial agonist of cannabinoid receptors in mouse brain. Eur J Pharmacol 323:R3–R4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celofiga A, Koprivsek J, Klavz J. (2014) Use of synthetic cannabinoids in patients with psychotic disorders: case series. J Dual Diagn 10:168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D (1971). Lectures on Biostatistics: An Introduction to Statistics with Applications in Biology and Medicine. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK.

- Comer SD, Burke TF, Lewis JW, Woods JH. (1992) Clocinnamox: a novel, systemically-active, irreversible opioid antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 262:1051–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan J, Deng H, Gatley SJ, Makriyannis A, Akinfeleye T, Bruneus M, Dimaio AA, Gifford AN. (2006) Evaluation of the in vivo receptor occupancy for the behavioral effects of cannabinoids using a radiolabeled cannabinoid receptor agonist, R-[125/131I]AM2233. Synapse 60:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falenski KW, Thorpe AJ, Schlosburg JE, Cravatt BF, Abdullah RA, Smith TH, Selley DE, Lichtman AH, Sim-Selley LJ. (2010) FAAH-/- mice display differential tolerance, dependence, and cannabinoid receptor adaptation after delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and anandamide administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:1775–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan F, Compton DR, Ward S, Melvin L, Martin BR. (1994) Development of cross-tolerance between delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol, CP 55,940 and WIN 55,212. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 271:1383–1390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman MJ, Rose DZ, Myers MA, Gooch CL, Bozeman AC, Burgin WS. (2013) Ischemic stroke after use of the synthetic marijuana “spice”. Neurology 81:2090–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost JM, Dart MJ, Tietje KR, Garrison TR, Grayson GK, Daza AV, El-Kouhen OF, Yao BB, Hsieh GC, Pai M, et al. (2010) Indol-3-ylcycloalkyl ketones: effects of N1 substituted indole side chain variations on CB(2) cannabinoid receptor activity. J Med Chem 53:295–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerostamoulos D, Drummer OH, Woodford NW. (2015) Deaths linked to synthetic cannabinoids. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 11:478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin G, Atkinson PJ, Showalter VM, Martin BR, Abood ME. (1998) Evaluation of cannabinoid receptor agonists and antagonists using the guanosine-5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)-triphosphate binding assay in rat cerebellar membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 285:553–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grim TW, Samano KL, Ignatowska-Jankowska B, Tao Q, Sim-Selly LJ, Selley DE, Wise LE, Poklis A, Lichtman AH. (2016) Pharmacological characterization of repeated administration of the first generation abused synthetic cannabinoid CP47,497. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 27:217–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. (1991) Characterization and localization of cannabinoid receptors in rat brain: a quantitative in vitro autoradiographic study. J Neurosci 11:563–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Little MD, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR, Rice KC. (1990) Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:1932–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huestis MA, Gorelick DA, Heishman SJ, Preston KL, Nelson RA, Moolchan ET, Frank RA. (2001) Blockade of effects of smoked marijuana by the CB1-selective cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR141716. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronstrand R, Roman M, Andersson M, Eklund A. (2013) Toxicological findings of synthetic cannabinoids in recreational users. J Anal Toxicol 37:534–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law R, Schier J, Martin C, Chang A, Wolkin A, Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (2015) Notes from the field: increase in reported adverse health effects related to synthetic cannabinoid use—United States, January–May 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 64:618–619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis A, Peterson BL, Couper FJ. (2014) XLR-11 and UR-144 in Washington state and state of Alaska driving cases. J Anal Toxicol 38:563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madia PA, Dighe SV, Sirohi S, Walker EA, Yoburn BC. (2009) Dosing protocol and analgesic efficacy determine opioid tolerance in the mouse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 207:413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. (1990) Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 346:561–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer KA, Russo RR, Adhvaryu DV. (2014) Smoking synthetic marijuana leads to self-mutilation requiring bilateral amputations. Orthopedics 37:e391–e394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monory K, Tzavara ET, Lexime J, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Borsodi A, Hanoune J. (2002) Novel, not adenylyl cyclase-coupled cannabinoid binding site in cerebellum of mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 292:231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PT, Schmid CL, Raehal KM, Selley DE, Bohn LM, Sim-Selley LJ. (2012) β-arrestin2 regulates cannabinoid CB1 receptor signaling and adaptation in a central nervous system region-dependent manner. Biol Psychiatry 71:714–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar M, Kumar P, Sunkaraneni S, Sirohi S, Walker EA, Yoburn BC. (2007) Opioid agonist efficacy predicts the magnitude of tolerance and the regulation of mu-opioid receptors and dynamin-2. Eur J Pharmacol 563:92–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rang HP. (2006) The receptor concept: pharmacology’s big idea. Br J Pharmacol 147 (Suppl 1):S9–S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawls SM, Cabassa J, Geller EB, Adler MW. (2002) CB1 receptors in the preoptic anterior hypothalamus regulate WIN 55212-2 [(4,5-dihydro-2-methyl-4(4-morpholinylmethyl)-1-(1-naphthalenyl-carbonyl)-6H-pyrrolo[3,2,1ij]quinolin-6-one]-induced hypothermia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 301:963–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi-Carmona M, Barth F, Héaulme M, Shire D, Calandra B, Congy C, Martinez S, Maruani J, Néliat G, Caput D, et al. (1994) SR141716A, a potent and selective antagonist of the brain cannabinoid receptor. FEBS Lett 350:240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MD, Trecki J, Edison LA, Steck AR, Arnold JK, Gerona RR. (2015) A common source outbreak of severe delirium associated with exposure to the novel synthetic cannabinoid ADB-PINACA. J Emerg Med 48:573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selley DE, Rorrer WK, Breivogel CS, Zimmer AM, Zimmer A, Martin BR, Sim-Selley LJ. (2001) Agonist efficacy and receptor efficiency in heterozygous CB1 knockout mice: relationship of reduced CB1 receptor density to G-protein activation. J Neurochem 77:1048–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selley DE, Stark S, Sim LJ, Childers SR. (1996) Cannabinoid receptor stimulation of guanosine-5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate binding in rat brain membranes. Life Sci 59:659–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks KG, Winston D, Heidingsfelder J, Behonick G. (2015) Case reports of synthetic cannabinoid XLR-11 associated fatalities. Forensic Sci Int 252:e6–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim LJ, Hampson RE, Deadwyler SA, Childers SR. (1996) Effects of chronic treatment with delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol on cannabinoid-stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS autoradiography in rat brain. J Neurosci 16:8057–8066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolevsky T, Prasolov I, Rodchenkov G. (2015) Study on the phase I metabolism of novel synthetic cannabinoids, APICA and its fluorinated analogue. Drug Test Anal 7:131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takematsu M, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS, Schechter JM, Moran JH, Wiener SW. (2014) A case of acute cerebral ischemia following inhalation of a synthetic cannabinoid. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 52:973–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BF, Wiley JL. (2014) Heat degradants of synthetic cannabinoids. DOI: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.10.031. [Google Scholar]

- Trecki J, Gerona RR, Schwartz MD. (2015) Synthetic cannabinoid-related illnesses and deaths. N Engl J Med 373:103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Zernig G, Young AM. (1998) In vivo apparent affinity and efficacy estimates for mu opiates in a rat tail-withdrawal assay. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 136:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westin AA, Frost J, Brede WR, Gundersen POM, Einvik S, Aarset H, Slørdal L. (2015) sudden cardiac death following use of the synthetic cannabinoid MDMB-CHMICA. J Anal Toxicol 40:86–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Martin BR. (2003) Cannabinoid pharmacological properties common to other centrally acting drugs. Eur J Pharmacol 471:185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Marusich JA, Lefever TW, Antonazzo KR, Wallgren MT, Cortes RA, Patel PR, Grabenauer M, Moore KN, Thomas BF. (2015) AB-CHMINACA, AB-PINACA, and FUBIMINA: affinity and potency of novel synthetic cannabinoids in producing Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol-like effects in Mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 354:328–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Marusich JA, Lefever TW, Grabenauer M, Moore KN, Thomas BF. (2013) Cannabinoids in disguise: Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol-like effects of tetramethylcyclopropyl ketone indoles. Neuropharmacology 75:145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer A, Zimmer AM, Hohmann AG, Herkenham M, Bonner TI. (1999) Increased mortality, hypoactivity, and hypoalgesia in cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:5780–5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]