Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis can cause chronic pain, disability, fatigue and loss of productivity both in the workplace and at home. Fatigue, not joint pain, swelling or that there may be radiographic damage, is frequently mentioned by patients as their most debilitating problem. In the era prior to biologic therapy in rheumatoid arthritis, it was reported that 40% to 50% of individuals reported work loss within 10 years of the onset of their disease. Rheumatoid arthritis is not just associated with chronic pain and inability to function normally; there is a significant economic burden caused by the disease which affects society as well the individual. Work disability in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis occurs early and increases over time. Early, aggressive treatment has now become the norm in clinical practice with changes of medication dictated by measuring the presence of continued disease activity. The combination of adequately dosed methotrexate and a biologic agent, especially a TNFα inhibitor, has been shown to be far more effective than traditional disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in early and long-standing disease, with respect to clinical, radiologic and functional outcomes. Unfortunately, not all patients respond to all medications equally; indeed a patient may fail a number of medications, either alone or in combination, and then respond to another medication. For this reason, there is room in our therapeutic armamentarium for additional effective agents such as certolizumab pegol. The results of up to 100 weeks of treatment with certolizumab pegol with an emphasis on functional outcomes, is the focus of this review.

Keywords: certolizumab, rheumatoid arthritis, anti-TNF therapy, efficacy, safety, quality of life

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has a world-wide distribution which affects 0.5% to 1% of the population.1 It is a chronic, inflammatory disease of the joints, with systemic manifestations, which, if not appropriately treated, causes chronic pain, disability and loss of productivity.2–6 RA impacts all areas of the individual’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL), including limitation of social roles, both within the family and within society as a whole.7 Fatigue, not joint pain, swelling or that there may be radiographic damage, is frequently mentioned by patients as their most debilitating problem.8 The significant decrease in a patient’s quality of life, in active or disabling RA despite therapy, is similar to the poor quality of life experienced by individuals with multiple sclerosis or chronic ischemic heart disease; in addition there is a significant loss in the ability to maintain full-time employment.3,6 In the era prior to biologic therapy in RA, it was reported that 40% to 50% of individuals reported work loss within 10 years of the onset of their disease.9

RA is not just associated with chronic pain and inability to function normally; there is a significant economic burden caused by the disease which affects society as well the individual. Work disability in individuals with RA is approximately 30% to 40% at 5 years; a significant economic impact can be seen within the first year of symptoms of RA.10–12 Sixty-three billion dollars was spent directly or indirectly on RA in 2006 in the United States and approximately US$67 billion in Europe;6 world-wide, indirect costs such as loss of employment and the need for additional help at home, account for a minimum of half the total cost of RA.2,6,13 A recent analysis of a cross-sectional database in the US reported a loss of household income for individuals with RA of nearly 12%.14

It has been shown that individuals with RA are less productive at home with limitations of both household and family activities and participated less in avocational activities.9,15–18 With respect to the workplace, absenteeism (work days missed), although commonly used to assess productivity loss in RA,19 does not fully address the ramifications of having active RA. The decreased ability to be productive at work, termed presenteeism, accounts for almost half the productivity loss in patients with arthritis versus approximately 10% to 12% due to absenteeism.20

Early, aggressive treatment of RA has now become the norm in clinical practice with changes of medication dictated by measuring the presence of continued disease activity.21–35 The combination of adequately dosed methotrexate (MTX) and a biologic agent, especially a tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) inhibitor (TNF-I) has been shown to be far more effective than traditional disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as MTX, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine or leflunomide, either alone or in combination, both in early and long-standing disease, with respect to clinical, radiologic and functional outcomes.24,28,30,35,36 For the patient with RA, functional outcomes are most important on a day-to-day basis. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of TNF-I in combination with MTX in improving functional status of individuals with RA both with respect to their activities of daily living and employability.3,37–39

Unfortunately, not all patients respond to all medications, equally; indeed a patient may fail a number of medications, either alone or in combination, and then respond to another medication.40–45 For this reason, there is room in our therapeutic armamentarium for additional effective agents such as certolizumab pegol (CZP) (Cimzia®; UCB Pharma, Smyrna, GA).

Pharmacology, mode of action, pharmacokinetics of certolizumab pegol

CZP is a PEGylated Fab´ with specificity for human TNFα; it does not have a crystallizable fragment (Fc). The Fab´ is produced in an E. coli system which should allow for large-scale and cost-effective production of the antibody.46 Fab´s are generally limited as therapeutic modalities in chronic inflammatory diseases such as RA, because of their clearance from plasma, which usually occurs within several hours. Monomethoxy-polyethylene glycol (PEG) confers a long in vivo half-life to conjugated proteins by reducing immunogenicity and proteolysis; it has also been shown to modulate the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of antibody fragments.46 CZP is composed of a Fab´ fragment produced in E. coli attached to a PEG moiety with a molecular weight of 40 kDa, two branches of 20 kDa each. In order to protect the molecule from the attachment of the PEG affecting the biologic properties of the Fab´, the Fab´ component of CZP has been engineered to contain a free cysteine residue in the hinge region which allows attachment of the PEG at a site removed from the antigen binding site, which has been shown to have no effect on the affinity of the molecule.47 The PEG moiety is attached to the Fab´ at a specific point at the Fab´ C terminus; it does not interact directly with the surface of the Fab´, which remains unaffected by any interaction, rearrangement or modification by the PEG moiety.47 The chemical structure of CZP is distinctly different from other TNF-I approved for use in RA.

CZP effectively neutralizes both soluble and membrane bound TNFα using in vitro assay systems, similar to other TNF-I; CZP is twice as potent as etanercept in inhibiting membrane bound TNFα. As opposed to other approved TNF-I, CZP does not mediate cell-dependent and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, does not cause apoptosis of activated human peripheral blood lymphocytes or monocytes in vitro, or affect polymorphonuclear cell integrity.48

CZP, administered subcutaneously, has a half-life of approximately 14 days which allows for administration every 2 to 4 weeks; PEGylation may contribute to the preferential distribution of CZP in inflamed tissues seen in animal models.49 A significant exposure-response relationship has been demonstrated for CZP in RA which supports dosing of CZP 200 mg every 2 weeks after a loading dose of 400 mg at weeks 0, 2 and 4 as well as supporting a dose of 400 mg every 4 weeks.50

The focus of this review is the long-term use of CZP in the treatment of RA, patient considerations and the impact on quality of life. The data pertaining to this topic is derived from three pivotal trials which either investigated CZP 400 mg monthly monotherapy versus placebo in DMARD failures for 52 weeks or two trials which explored CZP 400 mg given at weeks 0, 2, and 4 weeks and then each 2 weeks utilizing 200 or 400 mg of CZP plus MTX compared to MTX plus placebo in MTX incomplete responders; one study was of 52 weeks duration and the other of 24 weeks’ duration. The combination studies investigated clinical, radiographic and patient reported outcomes. The monotherapy trial investigated clinical and patient reported outcomes. In order to understand the patient reported outcomes, it is necessary to understand how each of the three studies was conducted and their results, which are summarized next.

Certolizumab pegol used as monotherapy in RA (FAST4WARD)51

A prospective, double blind, 24 week, randomized, placebo controlled study was conducted in 220 patients who had previously failed at least one DMARD for lack of efficacy or intolerance; DMARDs had to be discontinued for ≥28 days or ≥5 half lives, whichever was longer. Patients had adult RA for at least 6 months and had >9 tender and swollen joints and either ≥45 minutes of morning stiffness, ESR ≥28 or C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 1 mg/dL. Ethical review board approval was obtained at each center and all patients signed informed consent.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive lyophilized subcutaneous CZP 400 mg (n = 111) or placebo (n = 109) every 4 weeks until week 20. Patients were excluded if they had a current infection, history of chronic or serious infection, positive purified protein derivative (PPD) defined by local standards, a chest x-ray suggesting tuberculosis, prior treatment with TNF- I or other biological therapy within 6 months. Stable corticosteroids (≤10 mg prednisone per day), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and analgesics were allowed. Patients who completed the study, or who completed at least 12 weeks and withdrew for reasons other than an adverse event, could enter a long-term extension trial and receive CZP each 4 weeks subcutaneously.

The primary outcome was the ACR20 response at week 24.52 Secondary endpoints included ACR50/70 response, DAS(ESR)3,53 safety and patient reported outcomes including physical function (Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI)),54 patient reported pain (100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) where 0 = no pain and 100 the worst pain imaginable), modified Brief Pain Inventory (mBPI), fatigue measured by the Fatigue Assessment Scale (11 point Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) (0 = no fatigue to 10 = fatigue as bad as you can imagine),55 and health related quality of life (HRQoL − Short-Form 36 item questionnaire (SF-36));56,57 the SF-36 evaluates 8 health concepts: physical function, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional and mental health. The 8 domain scores are grouped into 2 summary component scores which are termed the Physical and Mental Component Summaries (PCS and MCS), respectively. The scores in the SF-36 domains range from 0 to 100 with the higher the score indicating a better health related quality of life. Post hoc analyses included the per cent of patients who achieved Minimal Clinically Important Differences (MCID) at week 24 in HAQ-DI (≥0.22 point decrease),58 arthritis pain (>10 point decrease),59 SF-36 domain (≥5 point increase), physical and mental component summary (PCS and MCS) scores (>2.5 point increase)56,57 and FAS (≥1 point decrease).60

Efficacy analyses were performed on the modified intent to treat (mITT) population (randomized patients who took ≥1 dose of study medication); a non-responder imputation (NRI) was used for the primary outcome. As part of the post-hoc analysis, the proportions of patients reporting improvements ≥ MCID in HAQ-SI, VAS pain, SF-36 and FAS were compared between treatment groups.

Patient demographics were similar between the two treatment groups (Table 1). The study met its primary endpoint at week 24; the ACR20 response in patients treated with CZP was 45.5% versus 9.3% in patients treated with placebo (P < 0.001). ACR50 responses were seen in 22.7% of CZP treated patients versus 3.7% in placebo treated patients (P < 0.001) and ACR 70 in 5.5% CZP treated patients versus 0% in those treated with placebo (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics in FAST4WARD

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 109) |

CZP 400 mg (n = 111) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years) | 54.9 | 52.7 |

| Female (%) | 89 | 78.4 |

| Rheumatoid factor + (%) | 100 | 100 |

| Disease duration (mean years) | 10.4 | 8.7 |

| Number prior DMARDs (mean) | 2.1 | 2 |

| Prior MTX use (%) | 81.7 | 82 |

| Glucocorticoid use (%) | 58.7 | 55.9 |

| Tender joints | 28.3 | 29.6 |

| Swollen joints | 19.9 | 21.2 |

| Patient global (1–5) (mean) | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| Physician global (1–5) (mean) | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| Patient assessment of pain | 54.8 | 58.2 |

| HAQ-DI (mean) | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| DAS28 (ESR)3 (mean) | 6.3 | 6.3 |

| ESR (geometric mean) | 35.6 | 30.9 |

Abbreviations: HAQ-DI, health assessment questionnaire – disability index; DAS28 (ESR)3, disease activity score – 3 variable utilizing ESR; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MTX, methotrexate.

Patient reported outcomes (PRO) were investigated in depth in this study. HAQ-DI responses were improved statistically significantly and were clinically meaningful in the CZP versus placebo treated patients as early as week 1 and were maintained through week 24 (Table 2). Similar changes in favor of CZP were seen in arthritis pain, measured by VAS 0–100 by week 1, which was maintained to week 24. Significantly more patients treated with CZP achieved a clinically meaningful decrease in arthritis pain at week 24 (Table 2). The improvement in pain with CZP versus placebo was seen by day 2. HRQoL improvements were significantly better in patients treated with CZP versus those treated with placebo at week 24 including all eight domains of the SF-36 (p < 0.01). There were statistically significant differences in both MCS and PCS which were clinically significant at week 24 (Table 2). Similar changes were seen in the FAS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Functional outcomes with certolizumab in pivotal trial

| Outcome | Mono | Mono | Mono | Rapid 2 | Rapid 2 | Rapid 2 | Rapid 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Patient reported outcome | CZP 400 | Placebo | p value | CZP 200 | CZP 400 | Placebo | P value |

| HAQ-DI week 1 | −0.23 | +0.04 | P < 0.001 | NS | NS | NS | P ≤ 0.001 |

| HAQ-DI week 24 | −0.36 | +0.13 | P < 0.001 | −0.5 | −0.5 | −0.14 | P ≤ 0.001 |

| HAQ-DI decrease > 0.22 | 49% | 12% | P < 0.001 | 57% | 53% | 11% | P ≤ 0.001 |

| Arthritis pain (VAS 0–100) wk 1 | −16.7 | −5.2 | P < 0.001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Arthritis pain (VAS 0–100) wk 24 | −20.6 | 1.7 | P < 0.001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| MCID in pain week 24 | 47% | 17% | P < 0.001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| MCID SF-36 PCS week 24 | 46% | 16% | P < 0.001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| MCID SF-36 MCS week 24 | 34% | 7% | P < 0.001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Increase in PCS week 24 | NS | NS | 5.2 | 5.5 | 0.9 | P ≤ 0.001 | |

| Increase in PF week 24 | NS | NS | 12.1 | 12.4 | 0.6 | P ≤ 0.001 | |

| FAS mean change week 24 | −1.69 | −0.27 | P < 0.001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| MCID FAS change week 24 | 46% | 17% | P < 0.001 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Abbreviations: HAQ-DI, health assessment questionnaire – disability index; MCID, minimally clinical important difference; PCS, physical component score; MCS, mental component score; FAS, fatigue activity score; PF, patient function.

In summary this study showed that patients treated with CZP subcutaneously 400 mg each 4 weeks as monotherapy had statistically superior clinical and functional responses compared to patients treated with placebo at the primary endpoint of 24 weeks; the responses were significant by week 1 and maintained significance through week 24.

Certolizumab pegol used in combination with MTX in RA (RAPID 1)61

A phase 3, prospective, double blind, randomized, parallel-group, 52-week, placebo-controlled study was conducted in 982 patients who had an incomplete response to MTX monotherapy who were treated with either of two dose regimens of the lyophilized form of CZP or placebo in combination with MTX. Patients were randomized 2:2:1 to treatment with CZP subcutaneously 400 mg plus MTX at weeks 0, 2 and 4 and then every 2 weeks at either 200 or 400 mg of CZP or placebo. Patients had to have active RA diagnosed by the ACR 1987 criteria for at least 6 months but no longer than 15 years with ≥9 tender and swollen joints and either ESR ≥ 30 mm/hour or C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 1.5 mg/dL. All patients were required to have taken MTX ≥ 10 mg per week for at least 6 months which was stable for the 2 months prior to randomization. DMARDs, other than MTX, were withdrawn at least 28 days prior to randomization (leflunomide 6 months unless treated with a cholestyramine wash-out). Ethical review board approval was obtained at each center and all patients signed informed consent. Patients were excluded if they had a current infection, history of chronic or serious infection, positive purified protein derivative (PPD) defined by local standards, a chest x-ray suggesting tuberculosis, prior treatment with TNF-I or other biological therapy within 6 months or had failed prior TNF-I therapy. Patients who had a history of malignancy, demyelinating disease, blood dyscrasias or severe, progressive or uncontrolled renal, hepatic, hematologic, gastrointestinal, endocrine, pulmonary, cardiac, neurologic or cerebral disease were also excluded. Stable corticosteroids (≤10 mg prednisone per day), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and analgesics were allowed. Patients who did not achieve an ACR20 response at weeks 12 and 14 were forced to withdraw from the study at week 16. Patients who withdrew at week 16, or who completed 52 weeks of the trial, could enter a long-term extension trial and receive 400 mg of CZP each 2 weeks subcutaneously. Patients who withdrew early had a radiographic assessment performed at the time they withdrew and at week 52.

Co-primary endpoints were the ACR20 response at week 24 and the mean change from baseline in the modified total Sharp score (mTSS) at week 52.62 Secondary endpoints included the change in the mTSS at week 24, change from baseline in the HAQ-DI at weeks 24 and 52 and ACR50/70 responses at weeks 24 and 52. Efficacy analyses were performed on the modified intent to treat (mITT) population (randomized patients who took ≥1 dose of study medication); an NRI was used for the primary outcome.

Patient demographics were similar between the two treatment groups and similar to patients randomized to the monotherapy study (Table 1) except duration of disease was a mean 6.2 years and approximately 80% were rheumatoid factor positive; the mean dose of MTX was approximately 13.5 mg per week in each group.

Sixty-five percent of patients randomized to CZP 200 mg plus MTX and 70% of patients randomized to CZP 400 mg plus MTX completed 52 weeks of study compared to 22% of patients who were treated with placebo plus MTX. The study met its primary clinical endpoint at week 24; the ACR20 response in patients treated with CZP 200 plus MTX was 58.8% and 60.8% in those treated with CZP 400 mg plus MTX versus 13.6% in patients treated with placebo plus MTX (P < 0.001). These responses remained significant through week 52. ACR50 and ACR70 responses were also significantly better for both doses of CZP compared to MTX plus placebo at week 24 (P < 0.001). ACR20 and ACR50 responses for CZP 200 and 400 mg plus MTX were statistically better than MTX plus placebo by week 1; ACR70 responses for both active medication groups were statistically superior to MTX plus placebo by week 4 (CZP 200 plus MTX) or 6 (CZP 400 plus MTX). Maximum ACR20/50/70 responses for both CZP regimens were reached by weeks 14 to 20. There was no difference in the ACR response rates at any time point for CZP 200 plus MTX compared to 400 mg CZP plus MTX.

The co-primary radiographic endpoint was also reached, At week 52, the mean change in the mTSS was 0.4 Sharp units in the patients treated with CZP 200 plus MTX, 0.2 Sharp units in the patients treated with CZP 400 plus MTX and 2.8 Sharp units in patients treated with placebo plus MTX (P < 0.001).

Patient reported outcomes were investigated in this study. HAQ-DI responses were improved statistically significantly and were clinically meaningful in the both CZP groups versus placebo treated patients as early as week 1 and were maintained through week 52. HAQ-DI decreased by 0.18 units in patients treated with placebo plus MTX at week 52 compared to a decrease of 0.6 and 0.63 units in patients treated with CZP 200 and 400 mg plus MTX respectively (P < 0.001 for both CZP groups versus placebo).

In summary this study showed that patients treated with CZP subcutaneously 400 mg at weeks 0, 2 and 4 and then either 200 or 400 mg CZP subcutaneously plus MTX in patients with an incomplete response to MTX had clinically and statistically significant improvements in clinical, radiographic and functional responses compared to patients treated with placebo and continued MTX. The responses were significant by week 1 and maintained through week 52 in the clinical and functional responses and by 24 weeks, and maintained until week 52, for the radiographic response.

Certolizumab pegol used in combination with MTX in RA (RAPID 2)63

A phase 3, prospective, double blind, randomized, parallel-group, 24-week, placebo-controlled study was conducted in 619 patients who had an incomplete response to MTX monotherapy and who were treated with either of two dose regimens of the liquid form of CZP or placebo in combination with MTX. Patients were randomized 2:2:1 to treatment with CZP subcutaneously 400 mg plus MTX at weeks 0, 2 and 4 and then every 2 weeks with either 200 or 400 mg of CZP plus MTX or placebo plus MTX. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were similar to those required in RAPID 1 as noted above. Ethical review board approval was obtained at each center and all patients signed informed consent. Patients who did not achieve an ACR20 response at weeks 12 and 14 were forced to withdraw from the study at week 16. Patients who withdrew at week 16, or who completed 24 weeks of the trial, could enter a long-term extension trial and receive 400 mg of CZP each 2 weeks subcutaneously plus MTX.

The primary endpoint was the ACR20 response at week 24. Secondary endpoints included ACR50 and 70 responses, mean change from baseline in the mTSS, HRQoL (using the SF-36), and HAQ-DI at week 24. Minimally clinically important differences (MCID) were defined as previously with a decrease of ≥0.22 points from baseline in the HAQ-DI and improvements of ≥2.5–5 in the PCS and MCS and ≥5.0 to 10.0 in patient function (PF) scores; mTSS were performed at baseline and week 24 or withdrawal. Efficacy analyses were performed on the modified intent to treat (mITT) population (randomized patients who took ≥1 dose of study medication); a NRI was used for the primary outcome. Patient demographics were similar between the two treatment groups and similar to patients randomized to the Rapid 1 study as above. Modified TSS at baseline was 46.5, 39.6 and 46.7 with an estimated yearly progression (mTSS/year) of 8.7, 6.6 and 7.4 in the in the MTX plus placebo, CZP 200 and CZP 400 mg groups, respectively.

Seventy-one percent of patients randomized to CZP 200 mg plus MTX and 73.6% of patients randomized to CZP 400 mg plus MTX completed 24 weeks of study compared to 13.4% of patients who were treated with placebo plus MTX. The study met its primary clinical endpoint at week 24; the ACR20 response in patients treated with CZP 200 plus MTX was 57.3%, and, 57.6% in those treated with CZP 400 mg plus MTX, versus 8.7% in patients treated with placebo plus MTX (P < 0.001). ACR50 and ACR70 responses were also significantly better for both doses of CZP compared to placebo at week 24 (P < 0.01). ACR20 responses for CZP 200 plus MTX were statistically better than MTX plus placebo by week 1 (P ≥ 0.01); ACR50 and 70 responses for both active medication groups were statistically superior to MTX plus placebo by week 6 (CZP 200 plus MTX) and week 20 (CZP 400 plus MTX) (P ≤ 0.01). There was no statistical difference in the ACR response rates at any time point for CZP 200 plus MTX compared to 400 mg CZP plus MTX.

Radiographic progression, a secondary endpoint, was also reached, At week 24, the mean change in the mTSS was 0.2, –0.4 and 1.2 Sharp units in the patients treated with CZP 200 and 400 mg plus MTX and placebo plus MTX, respectively (P < 0.001). The cumulative probability plots at week 24 indicated that more patients in the placebo plus MTX group had progression than patients in either CZP plus MTX group. The difference in progression favoring CZP plus MTX was seen as early as week 16.

Patient reported outcomes were investigated in depth in this study. HAQ-DI responses were improved statistically significantly and were clinically meaningful in the CZP versus placebo treated patients as early as week 1 and were maintained through week 24 (P ≤ 0.001). By week 24 there was a statistically significant difference in the per cent of patients who achieved an MCID in HAQ-DI in the CZP plus MTX treated patients versus placebo plus MTX treated patients (P ≤ 0.001). In addition, both CZP plus MTX treated groups achieved a significantly improved response in SF-36 PCS, MCS and PF domain scores compared to placebo plus MTX at weeks 12 and 24 (P ≤ 0.001). HAQ related quality of life (HRQoL) improvements were significantly better in patients treated with CZP versus those treated with placebo at week 24 including all eight domains of the SF-36 (P < 0.01). There were statistically significant differences in both MCS and PCS which were clinically significant at week 24 (Table 2).

In summary this study showed that patients treated with CZP subcutaneously 400 mg at weeks 0, 2 and 4 and then either 200 or 400 mg CZP subcutaneously plus MTX in patients with an incomplete response to MTX had clinically and statistically significant improvements in clinical, radiographic and functional responses compared to patients treated with placebo and continued MTX after 24 weeks. The responses were significant by week 1 and maintained through week 24 in the clinical and functional responses and by 16 weeks and maintained until week 24 for the radiographic response.

Certolizumab pegol used in combination with MTX in RA (RAPID 1): Long-term use, patient considerations and the impact on quality of life

Patients who completed 52 weeks of therapy in RAPID 1 or who failed to achieve an ACR20 response at week 12 and 14 in RAPID 1 and who were withdrawn at week 16 were eligible to enter an open-label extension in which all patients received CZP 400 mg each two weeks plus MTX weekly. There were 255 patients treated with CZP 200 mg and 274 treated with CZP 400 mg who completed 52 weeks of therapy in the double-blind portion of whom 243 and 265 in the respective groups entered the open-label extension.64 Almost 90% of these patients remained in the extension trial at the time of this analysis (August 2007) with a mean drug exposure of approximately 112 weeks. There were 168 patients who were originally treated with 200 mg of CZP each 2 weeks plus MTX for 52 weeks who were subsequently treated with 400 mg of CZP plus MTX for a minimum of 52 weeks (total duration of therapy with CZP of at least 2 years) and 177 patients treated originally in the double-blind trial, and subsequently in the open-label extension, with 400 mg of CZP plus MTX for a minimum of 2 years.

As would be expected in a completer’s analysis such as this, there was a significant clinical response in both groups (200 and 400 mg of CZP at week 52) which was maintained through week 100. ACR20/50/70 responses were seen in 83; 82, 56;58 and 30; 30 in the 200 and 400 mg groups at week 52 respectively and 77;79, 60;55 and 36;35 at week 100, respectively. EULAR responses were seen in 96%–98% at both week 52 and 100 in both groups; DAS28 remission was observed in 23 and 21% of patients treated with CZP 200 and 400 mg each 2 weeks at week 52, respectively and in 29 and 25% of the respective groups at week 100. The ACR20/50/70 response rates were seen rapidly by weeks 12 to 16.

The impact of CZP over time on quality of life was investigated in the open-label, long-term extension to the RAPID1 trial.65 In this report, the authors analyzed HRQoL and fatigue responses over 2 years in 345 patients who completed treatment with CZP 200 or 400 mg plus MTX for 52 weeks of the double-blind, controlled trial and who then enrolled in the open-label study and received CZP 400 mg plus MTX. All patients included in this post-hoc analysis received CZP for ≥2 years. As previously, HRQoL was assessed by the SF-36 and fatigue by the FAS. Mean SF-36 scores, changes from baseline in SF-36 and FAS scores, and proportion of patients reporting improvements greater than or equal to the MCID in SF-36, PCS and MCS were determined and compared to the US population norm, based on age and sex. HRQoL was assessed at week 12 and each 4 weeks to week 52 and then each 12 weeks until week 100. FAS was assessed each 1 to 2 weeks to week 12 and then at then similarly to HRQoL. The results were imputed using the last observation carried forward method.

In the CZP 200 and 400 mg plus MTX groups, respectively, baseline HAQ-DI was 1.6 and 1.7; baseline mean SF-36 PCS was 31.1 and 30.3; baseline mean SF-36 MCS was 39.9 and 39.3 and baseline mean FAS was 6.5 and 6.4 (Table 3). When compared to the normative values, based on age and sex in the United States, the largest decrease in domain scores in these patients, prior to therapy, was seen in the role physical, physical function and bodily pain in the PCS score and in the role emotional domain in the MCS score.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of completers with 2 years of exposure in RAPID 1

| CZP 200 + MTX (n = 168) |

CZP 400 mg + MTX (n = 177) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean yrs) | 50.8 | 51.6 |

| Per cent female | 77.4 | 85.3 |

| Disease duration (mean yrs) | 5.9 | 5.9 |

| Number of prior DMARDs | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| MTX dose (mean mg/week) | 13.8 | 13.4 |

| Rheumatoid factor % | 81.5 | 85.9 |

| Tender joints (mean) | 31 | 32.3 |

| Swollen joints | 22.4 | 22.9 |

| DAS28 (median) | 7.00 | 7.00 |

| ESR (geometric mean) | 46 | 45.4 |

| HAQ-DI (mean) | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| SF-36 PCS (mean) | 31.1 | 30.3 |

| SF-36- MCS (mean) | 39.9 | 39.3 |

| FAS (mean) | 6.5 | 6.4 |

| PAAP (mean) | 63.3 | 63.4 |

Abbreviations: HAQ-DI, health assessment questionnaire – disability index; MCID, minimally clinical important difference; PCS, physical component score; MCS, mental component score; FAS, fatigue activity score; PAAP, patient assessment of pain; MTX, methotrexate.

There was rapid (by 12 weeks) and sustained improvements in HRQoL from baseline through 100 weeks of treatment. The mean change in the PCS score at week 100 was approximately 8.8 for patients initially randomized to CZP 200 plus MTX and approximately 10 for those initially randomized to CZP 400 plus MTX; changes in MCS were approximately 8.3 and 9 for the CZP 200 and CZP 400 mg plus MTX groups, respectively. As noted previously, patients initially treated with CZP 200 mg plus MTX were treated with CZP 400 mg every 2 weeks plus MTX in the OLE. There was no significant benefit observed in these patients with respect to improvement in their SF-36 scores in the second year of therapy with CZP 400 mg each 2 weeks plus MTX. By week 12, all domains showed improvement greater than the MCID. The greatest improvements were seen in the role physical, role emotional, bodily pain and vitality domains. The HRQoL level met or approached age and sex matched population norms in the vitality and mental health domains at weeks 12 and 100.

Improvement in fatigue was seen as early as week 1 and sustained through week 100. Both CZP doses were effective with a decrease in the FAS of 3.1 in the CZP 200 mg plus MTX group and of 2.9 in the CZP 400 mg plus MTX group at week 100 (MCID for FAS is 1). As noted with respect to HRQoL, patients treated with 200 mg CZP plus MTX in the double blind study, who had an improvement in FAS during the double-blind portion, did not have further improvement in FAS when escalated to CZP 400 mg plus MTX in the open-label extension.

In summary, this post hoc analysis indicates that statistically and clinically significant improvements in both HRQoL and fatigue occur rapidly with the use of CZP plus MTX, at either 200 or 400 mg each two weeks, and are sustained for a minimum of 100 weeks. The improvement in HRQoL was seen in both the mental and physical domains.

In another post-hoc analysis of the same data-set, physical function and pain improvement were the Patient’s Assessment of Arthritis Pain (PAAP66 visual analog scale (VAS 0–100).67 A HAQ-DI response ≥0.22 (the MCID for HAQ-DI) was seen in approximately 70% of patients at week 100, whether the patient was treated with 200 mg CZP plus MTX or 400 mg plus MTX for the first 52 weeks, and subsequently treated with CZP 400 mg plus MTX from week 52 to week 100. Clinically meaningful improvements in HAQ-DI were seen as early as week 1. The absolute change in HAQ-DI was approximately 0.7 in both groups, both at week 52 and week 100. Both groups of patients had a decrease in pain by approximately 39 points (as noted previously, an improvement of 10 points is clinically significant). As was seen with other efficacy measures, no additional improvement was noted in patients originally treated with CZP 200 mg plus MTX for the first 52 weeks who were subsequently treated with CZP 400 mg plus MTX from week 52 to 100.

Quality of life can be measured, as discussed previously, by changes in scales reported by patients in questionnaires such as the SF-36, HAQ-DI, PAAP and FAS. Another aspect, and perhaps more clinically important to a patient with RA, is their ability to perform their activities of daily living, either at home or work or both.

In the double-blind portion of both RAPID 1 and 2, the Work Productivity Survey (WPS-RA),68 a validated questionnaire that measures both RA related work and household productivity, was assessed at baseline and then each four weeks for the duration of the trials.69 The WPS-RA estimates productivity limitations associated with RA on paid jobs outside the home, on household work and on other social activities measures over the preceding month. Mean changes from baseline in missed days of household work, days with reduced household productivity, missed days of family/social/leisure activities, self-rated impact of RA on household work productivity, work absenteeism, work presenteeism and self-rated impact or RA on work productivity were measured on a 0 to 10 point scale (0 = no interference to 10 = complete interference.

The effects of both doses of CZP (200 and 400 mg) with MTX on household work and productivity and their affects on family, leisure and social activities, versus placebo plus MTX, were assessed in both RAPID 1 and RAPID 2; both doses were shown to be effective in improving these ramifications of RA.70 There was a decrease in full days missed of household duties per month from baseline to week 52 in the RAPID 1 study of 1.6 days in the placebo plus MTX group, 5.2 days in the CZP 200 plus MTX group and 5.4 days in the CZP 400 mg plus MTX group (P ≤ 0.05 of both CZP plus MTX groups versus placebo plus MTX). In addition, there was a statistically significant impact of either dose of CZP plus MTX versus placebo plus MTX (P ≤ 0.05 of both CZP plus MTX groups versus placebo plus MTX) with respect to decrease in days with reduced household productivity from baseline to week 52: placebo plus MTX = 3.2 days; CZP 200 mg plus MTX = 6 days; CZP 400 mg plus MTX = 6.7 days. Similarly, with respect to decreased days of missed family, social or leisure activities per month, there was a statistically significant decrease (P ≤ 0.05 of both CZP plus MTX groups versus placebo plus MTX) in the number of days missed: placebo plus MTX = 3.1 days; CZP 200 mg plus MTX 4.6 days; CZP 400 mg plus MTX 4 days. With respect to reduced interference of RA on productivity at home, there was a mean reduction of the rate of interference per month of 0.8 in the placebo plus MTX group versus 2.8 in the CZP 200 mg plus MTX group and 3.0 in the CZP 400 mg plus MTX group (P ≤ 0.05 of both CZP plus MTX groups versus placebo plus MTX). Over the full12 months there was a gain in full household work days versus placebo plus MTX of 52.1 days in the CZP 200 plus MTX arm and 44.5 days in the CZP 400 mg plus arm; approximately 37 days gained in both CZP plus MTX arms versus placebo plus MTX with respect to more productive days of household work and a gain of approximately 26 days in both CZP plus MTX groups versus placebo plus MTX in social/family/leisure days. All these changes were first seen by week four and became statistically significant by week 24. Similar changes were seen over the 26 weeks of the RAPID 2 trial.

Improvements in a patient’s ability to work, both with respect to absenteeism (absent from work) and productivity at work (presenteeism) is important to many individuals with RA as many are of working age and need to work for a number of reasons (day-to-day finances, affordable health insurance, self-worth, etc). The status of patients in RAPID 1 and 2 at baseline with respect to their employment status is shown in Table 4; approximately 40% of individuals in RAPID 1 and 35% on RAPID 2 were employed outside the home while 20% of patients in RAPID 1 and 24% in RAPID 2 were already unable to work because of their RA. The effect of both doses of CZP (200 and 400 mg) with MTX on absenteeism, presenteeism, and RA impact on work productivity was evaluated as well in RAPID 1 and 2.69 CZP 200 and 400 mg plus MTX were effective in improving these ramifications of RA, as well, versus placebo plus MTX. As shown in Table 4, baseline characteristics of patients with respect to absenteeism, presenteeism and RA impact on work productivity between RAPID 1 and RAPID 2 was similar.

Table 4.

Baseline employment status, work days missed and decreased productivity

| Baseline values | RAPID 1 N = 982 | RAPID 2 N = 619 |

|---|---|---|

| Employed (%) | 41.6 | 39.8 |

| Homemaker (%) | 14.4 | 7.3 |

| Retired | 20 | 28.1 |

| Unable to work due to RA | 21.2 | 24 |

| Not employed – other reasons | 2.8 | 0.8 |

| Number of days household work missed (mean) | 8.09 | 6.88 |

| Number of days with household productivity reduced ≥50% (mean) | 10.36 | 10.77 |

| Number of days of family, social or leisure activities missed (mean) | 6.08 | 4.97 |

| RA interference with household productivity (0–10; 0 = no interference) | 6.2 | 5.94 |

| Work absenteeism (mean days per month) | 3.92 | 3.26 |

| Work presenteeism (mean days per month) | 7.11 | 8.79 |

| RA interference with work productivity (0–10; 0 = no interference) | 5.22 | 5.46 |

There was a decrease in monthly absenteeism from baseline to week 52 in the RAPID 1 study of 0.1 days in the placebo plus MTX group, 2.1 days in the CZP 200 plus MTX group and 3.1 days in the CZP 400 mg plus MTX group (P ≤ 0.05 of both CZP plus MTX groups versus placebo plus MTX). In addition, there was a statistically significant impact of either dose of CZP plus MTX versus placebo plus MTX (P < 0.05 of both CZP plus MTX groups versus placebo plus MTX) with respect to decrease in presenteeism per month from baseline to week 52: placebo plus MTX 1.8 days; CZP 200 mg plus MTX = 5.1 days; CZP 400 mg plus MTX = 5.4 days. With respect to reduced interference of RA on productivity of paid work per month, there was a mean reduction of the rate of interference per month of 0.3 in the placebo plus MTX group versus 3.0 in the CZP plus MTX group and 2.7 in the CZP 400 mg plus MTX group; by week 52, patients treated with CZP 200 or 400 mg plus MTX had arthritis interference scores of 2.5 or 2.4 respectively compared with 5.2 in the placebo plus MTX arm (P ≤ 0.05 of both CZP plus MTX groups versus placebo plus MTX). Over the full 12 months, there was a cumulative gain in full days of paid work versus placebo plus MTX of 41.9 days in the CZP 200 plus MTX arm and 35.1 days in the CZP 400 mg plus arm; 29.4 day and 23 days for CZP 200 and 400 mg plus MTX versus MTX plus placebo in more productive days of work. All these changes were first seen by week four and became statistically significant by week 24. Similar changes were seen over the 26 weeks of the RAPID 2 trial.

Conclusion

The clinically meaningful improvements in HRQoL, HAQ-DI, FAS, PAAP, work and household productivity reported with the use of CZP plus MTX in these studies are of prime importance to individuals with RA; pain and fatigue significantly influences the quality of life of individuals with RA resulting in decreased physical and social function, depression, anxiety, and limitations in performing leisure activities and in employment. CZP plus MTX either at 200 mg or 400 mg every 2 weeks was statistically and clinically significantly superior to MTX plus placebo in improvements in each of these areas. Improvements were seen rapidly (within one to a few weeks depending upon the variable studies) and were sustained for the duration of both RAPID 1 and 2 and in the extension study with benefit persisting for a minimum of 100 weeks. There was no numerical or statistical difference between 200 or 400 mg CZP each two weeks in any of the outcomes reported; the lower dose was just as effective as the higher dose in all trials in which they were compared. For this reason, the approved dose of CZP in the United States is 200 mg subcutaneously each 2 weeks or 400 mg subcutaneously each month (total of 400 mg per month) after a loading dose of 400 mg on weeks 0, 2 and 4.

Studies exploring most of these outcomes have been performed with other medications used in the treatment of RA as noted previously. As not all patients respond to all medications, certolizumab pegol may be another option to treat patients with RA with expected improvement in clinical, radiologic and functional outcomes.

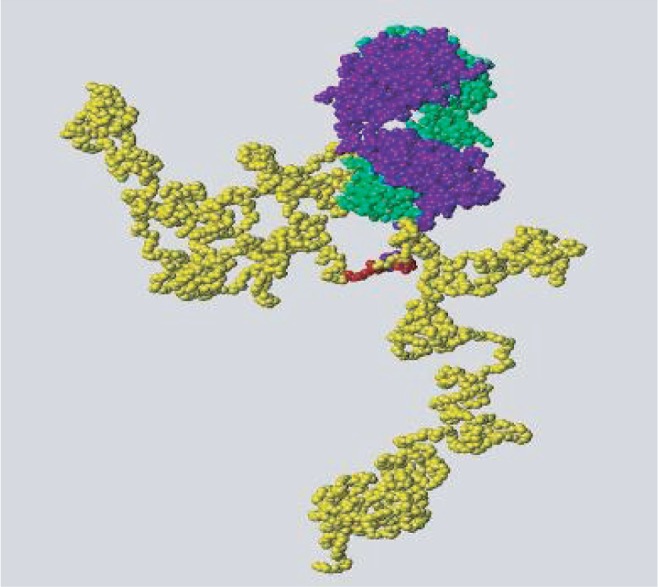

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of certolizumab pegol (CZP) (chains of the Fab´ fragment are green and blue; polyethylene glycol is shown in yellow).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The author has received clinical trial support from, and is a consultant to, UCB Pharma.

References

- 1.MacGregor AJ, Silman AJ. Classification and epidemiology. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH, editors. Rheumatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Elsevier Science; 2003. pp. 757–763. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlop DD, Manheim LM, Yelin EH, Song J, Chang RW. The costs of arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:101–113. doi: 10.1002/art.10913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavanaugh A, Han C, Bala M. Functional status and radiographic joint damage are associated with health economic outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:849–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kavanaugh A. Economic issues with new rheumatologic therapeutics. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:272–276. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3280be58ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacaille D. Arthritis and employment research: where are we? Where do we need to go? J Rheumatol. 2005;72(Suppl):42–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundkvist J, Kastang F, Kobelt G. The burden of rheumatoid arthritis and access to treatment: health burden and costs. Eur J Health Econ. 2008;8(Suppl 2):S49–S60. doi: 10.1007/s10198-007-0088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Deyo RA, Felson DT, Giannini EH, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(5):778–799. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirwan JR, Hewlett S. Patient perspective: reasons and methods for measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(5):1171–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sokka T, Kautiainen H, Mottonen T, Hannonen P. Work disability in rheumatoid arthritis 10 years after the diagnosis. J Rheumatol. 2009;26:1681–1685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albers JM, Kuper HH, Van Riel PL, Prevoo ML, van’t Hof MA, van Gestel AM, et al. Socio-economic consequences of rheumatoid arthritis in the first years of the disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38(5):423–430. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young A, Dixey J, Cox N, Davies P, Devlin J, Emery P, et al. How does functional disability in early rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affect patients and their lives? Results of 5 years of follow-up in 732 patients from the Early RA Study (ERAS) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39(6):603–611. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young A, Dixey J, Kulinskaya E, Cox N, Davies P, Devlin J, et al. Which patients stop working because of rheumatoid arthritis? Results of five years’ follow up in 732 patients from the Early RA Study (ERAS) Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(4):335–340. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.4.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kavanaugh A. Health economics: implications for novel antirheumatic therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 4):iv65–iv69. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.042440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Choi HK, Williams R. Household income and earnings losses among 6,396 persons with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1875–1883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habib G, Artul S, Ratson N, Froom P. Household work disability of Arab housewives with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(5):759–763. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0554-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soderlin MK, Kautiainen H, Skogh T, Leirisalo-Repo M. Quality of life and economic burden of illness in very early arthritis. A population based study in southern Sweden. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(9):1717–1722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Jaarsveld CH, Jacobs JW, Schrijvers AJ, van Albada-Kuipers GA, Hofman DM, Bijlsma JW. Effects of rheumatoid arthritis on employment and social participation during the first years of disease in The Netherlands. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37(5):848–853. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.8.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westhoff G, Listing J, Zink A. Loss of physical independence in rheumatoid arthritis: interview data from a representative sample of patients in rheumatologic care. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13(1):11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escorpizo R, Bombardier C, Boonen A, Hazes JM, Lacaille D, Strand V, et al. Worker productivity outcome measures in arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(6):1372–1380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Gignac MA, Anis AH. The indirect costs of arthritis resulting from unemployment, reduced performance, and occupational changes while at work. Med Care. 2006;44(4):304–310. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000204257.25875.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aletaha D, Eberl G, Nell VP, Machold KP, Smolen JS. Attitudes to early rheumatoid arthritis: changing patterns. Results of a survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(10):1269–1275. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.015131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC, et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1586–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breedveld FC. Should rheumatoid arthritis be treated conservatively or aggressively? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42(Suppl 2):ii41–ii43. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, Cohen SB, Pavelka K, van VR, et al. The PREMIER study: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):26–37. doi: 10.1002/art.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emery P, Salmon M. Early rheumatoid arthritis: time to aim for remission? Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(12):944–947. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.12.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Genovese MC, Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, et al. Etanercept versus methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: two-year radiographic and clinical outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(6):1443–1450. doi: 10.1002/art.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genovese MC, Bathon JM, Fleischmann RM, Moreland LW, Martin RW, Whitmore JB, et al. Longterm safety, efficacy, and radiographic outcome with etanercept treatment in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(7):1232–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van ZD, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JM, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3381–3390. doi: 10.1002/art.21405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, McMahon AD, Lock P, Vallance R, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9430):263–269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16676-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klareskog L, van der Heijde DM, de Jager JP, Gough A, Kalden J, Malaise M, et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9410):675–681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lard LR, Visser H, Speyer I, vander Horst-Bruinsma IE, Zwinderman AH, Breedveld FC, et al. Early versus delayed treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of two cohorts who received different treatment strategies. Am J Med. 2001;111(6):446–451. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00872-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Proudman SM, Conaghan PG, Richardson C, Griffiths B, Green MJ, McGonagle D, et al. Treatment of poor-prognosis early rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized study of treatment with methotrexate, cyclosporin A, and intraarticular corticosteroids compared with sulfasalazine alone. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(8):1809–1819. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1809::AID-ANR17>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smolen JS, Sokka T, Pincus T, Breedveld FC. A proposed treatment algorithm for rheumatoid arthritis: aggressive therapy, methotrexate, and quantitative measures. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21(5 Suppl 31):S209–S210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smolen JS. Objectives and strategies for rheumatoid arthritis therapy: yesterday vs. today. Drugs Today (Barc) 2003;39(Suppl B):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.St Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS, Maini RN, Bathon JM, Emery P, et al. Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(11):3432–43. doi: 10.1002/art.20568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, Durez P, Chang DJ, Robertson D, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):375–382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61000-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han C, Smolen JS, Kavanaugh A, van der HD, Braun J, Westhovens R, et al. The impact of infliximab treatment on quality of life in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(5):R103. doi: 10.1186/ar2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han C, Smolen J, Kavanaugh A, St Clair EW, Baker D, Bala M. Comparison of employability outcomes among patients with early or longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(4):510–514. doi: 10.1002/art.23541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yelin E, Trupin L, Katz P, Lubeck D, Rush S, Wanke L. Association between etanercept use and employment outcomes among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(11):3046–3054. doi: 10.1002/art.11285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Vollenhoven RF, Harju A, Brannemark S, Klareskog L. Treatment with infliximab (Remicade) when etanercept (Enbrel) has failed or vice versa: data from the STURE registry showing that switching tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers can make sense. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1195–1198. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.009589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hyrich K, Lunt M, Watson K, Symmons D, Silman A, for the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Registry Outcomes after switching from one anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agent to a second anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agent in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a large UK national cohort study. Arthitis Rheum. 2007;56:13–20. doi: 10.1002/art.22331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, Dougados M, Furie RA, Genovese MC, et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: Results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):2793–2806. doi: 10.1002/art.22025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Genovese MC, Becker JC, Schiff M, Luggen M, Sherrer Y, Kremer J, et al. Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1114–1123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schiff MH, Pritchard C, Huffstutter JE, Rodriguez-Valverde V, Durez P, Zhou X, et al. The 6-month safety and efficacy of abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who underwent a washout after anti-TNF therapy or were directly switched to abatacept: the ARRIVE trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Dec 15; doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.099218. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emery P, Keystone E, Tony HP, Cantagrel A, van VR, Sanchez A, et al. IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor biologicals: results from a 24-week multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(11):1516–1523. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chapman A, Antoniw P, Spitali M, West S, Stephens S, King D. Therapeutic antibody fragments with prolonged in vivo half-lives. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:780–783. doi: 10.1038/11717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bourne T, Fossati G, Nesbitt A. A PEGylated Fab’ fragment against tumor necrosis factor for the treatment of Crohn disease: exploring a new mechanism of action. BioDrugs. 2008;22(5):331–337. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200822050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nesbitt A, Fossati G, Bergin M, Stephens P, Stephens S, Foulkes R, et al. Mechanism of action of certolizumab pegol (CDP870): in vitro comparison with other anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(11):1323–1332. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nesbitt A, Fossati G, Brown D, Henry A, Palframan R, Stephens S. Effects of structure of convential anti-TNFs and certolizumab pegol on mode of action in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(Suppl 2):296. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lacroix B, Lovern M, Stockis A, Sargentini-Maier M, Karlsson M, Friberg L. Exposure-response modelling and simulations of the ACR20 response with different dosing regimens of certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(Suppl 11):FRI0110. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fleischmann R, Vencovsky J, van VR, Borenstein D, Box J, Coteur G, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol monotherapy every 4 weeks in patients with rheumatoid arthritis failing previous disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy: the FAST4WARD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):805–811. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.099291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Riel PL, van Gestel AM, van de Putte LB. Development and validation of response criteria in rheumatoid arthritis: steps towards an international consensus on prognostic markers. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35(Suppl 2):4–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.suppl_2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kirwan J, Reeback J. Stanford HealthAssessment Questionnaire modified to assess diability in British patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1986;25:206–209. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/25.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hewlett S, Hehir M, Kirwan J. Measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of scales in use. Arthitis Rheum. 2007;57:429–439. doi: 10.1002/art.22611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA: New England Medical Center/The Health Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SK. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s guide. Boston, MA: New England Medical Center/The Health Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wells G, Tugwell P, Kraag J, Baker P, Groh J, Redelmeier D. Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient’s perspective. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:557–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dworkin R, Turk D, Wyrwich K, Beaton D, Cleeland C, Farrar J, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wells G, Li T, Maxwell L, MacLean R, Tugwell P. Determining the minimal clinically important differences in activity, fatigue and sleep quality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:280–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keystone E, Heijde D, Mason D, Jr, Landewe R, Vollenhoven RV, Combe B, et al. Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate is significantly more effective than placebo plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a fifty-two-week, phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(11):3319–3329. doi: 10.1002/art.23964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van der Heijde DM, Van Riel PL, Nuver-Zwart IH, Gribnau FW, vad de Putte LB. Effects of hydroxychloroquine and sulphasalazine on progression of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1989;1(8646):1036–1038. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smolen JS, Landewe RB, Mease PJ, Brzezicki J, Mason D, Luijtens K, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: The RAPID 2 Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.101659. [cited 2009 Feb. 9]; Available from: URL:PM:19015207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keystone E, Schiff M, Mease P, van Vollenhoven RF, Desai C, Smolen JS. Combination therapy with certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate maintains long-term efficacy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a 2 year analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(Suppl 9) Abstract 981. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Strand V, Coteur G, Keininger DL. Health-related quality of life and fatigue benefits in rheumatoid arthritis patients were sustained over 2 years of treament with certolizumab pegol. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(Suppl 9) Abstract 975. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Chernoff M, Fried B, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(6):729–740. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mease P, Coteur G, Keininger DL. Improvements in physical function and pain reflief were sustained in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated for 2 years with certolizumab pegol. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(Suppl 9) Abstract 980. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Osterhaus J, Richard L, Purcaru O. Development and validation of the rheumatoid arthritis specific work productivity survey (WPS-RA) Arthritis Care Res. 2009 doi: 10.1186/ar2702. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smolen JS, Emery P, Kavanaugh A, Richard L, Purcaru O. Cetolizumab pegol with methotrexate improves performance at work in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(Suppl 9) doi: 10.1002/art.24828. Abstract 978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Emery P, Smolen JS, Kavanaugh A, Richard L, Purcaru O. Combination therpay with certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate improves household productivity and daily activities in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;58 Suppl 9. Abstract. 977 doi: 10.1002/art.24828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]