Abstract

Falls are the most common and expensive medical complication in stroke survivors. There is remarkably little information about what factors lead to a fall in stroke survivors. With few exceptions, the falls literature in stroke has focused on relating metrics of static balance and impairment to fall outcomes in the acute care setting or in community. While informative, these studies provide little information about what specific impairments in a stroke-survivor’s response to dynamic balance challenges lead to a fall. We identified the key kinematic characteristics of stroke survivors’ stepping responses following a balance disturbance that are associated with a fall following dynamic balance challenges. Stroke survivors were exposed to posteriorly-directed translations of a treadmill belt that elicited a stepping response. Kinematics were compared between successful and failed recovery attempts (i.e. a fall). We found that the ability to arrest and reverse trunk flexion and the ability to perform an appropriate initial compensatory step were the most critical response contributors to a successful recovery. We also identified 2 compensatory strategies utilized by stroke survivors to avoid a fall. Despite significant post-stroke functional impairments, the biomechanical causes of trip-related falls by stroke survivors appear to be similar to those of unimpaired older adults and lower extremity amputees. However, compensatory strategies (pivot, hopping) were observed.

Keywords: falls, stroke, kinematics, balance

INTRODUCTION

Nearly 50% of the 6.5 million stroke survivors living in the United States fall (Weerdesteyn, Niet et al. 2008) making falls the most common and expensive medical complication for them. Despite this, there is remarkably little information about the mechanisms leading to falls in stroke survivors.

Stroke survivors have known balance and stepping impairments following small balance disturbances including delayed and diminished muscle activation (Badke and Duncan 1983, Diener, Dichgans et al. 1984, Dietz and Berger 1984, Diener, Ackermann et al. 1985, Ikai, Kamikubo et al. 2003, Marigold, Eng et al. 2004, Marigold and Eng 2006), abnormal muscle activation patterns (Badke and Duncan 1983, Di Fabio 1987), decreased control of the trunk (Marigold and Eng 2006), and asymmetrical weight bearing (Mansfield and Maki 2009, Mansfield, Inness et al. 2011). The extent to which these characteristics contribute to falls is unknown. With few exceptions, falls literature in stroke has related metrics of static balance (stepping did not occur) and impairment (clinical metrics) to fall outcomes in the acute care setting and community (Ikai, Kamikubo et al. 2003, Marigold, Eng et al. 2004, Marigold, Eng et al. 2004, Marigold and Eng 2006, Weerdesteyn, Niet et al. 2008, Divani, Majidi et al. 2011, Persson, Hansson et al. 2011). However, it is not known if these metrics are appropriate predictors following postural disturbances that require stepping to avoid falling. Consequently, fall-prevention efforts and rehabilitation therapies may inadvertently be focused on changing variables that are the least likely to reduce falls in this population.

We have previously identified a set of causally related and clinically modifiable biomechanical variables that statistically discriminate a successful recovery (fall avoidance) from a failed stepping response (fall) following a trip in unimpaired older adults (Crenshaw, Rosenblatt et al. 2012, Grabiner, Bareither et al. 2012). We sought to extend this model to stroke survivors. To our knowledge, no other group has evaluated the biomechanical characteristics of stroke survivors’ response to balance disturbances that require a forward step similar to that evoked during a trip. The objective of the present study was to establish the extent to which variables that distinguish successful and failed stepping responses by stroke survivors differ from those previously described for unimpaired older adults. We exposed stroke survivors to posteriorly-directed perturbations of various magnitudes that required a forward directed stepping response to avoid a fall and compared kinematics between successful (Recovery) and failed (Fall) recovery attempts. We hypothesized that metrics previously described to be important in older adults (e.g. trunk flexion velocity and recovery step length) would best characterize successful and failed recovery attempts. In two secondary analyses, we compared clinical metrics of impairment (e.g. Berg) of Fallers and Non-Fallers and described the compensatory strategies utilized by stroke survivors.

METHODS

Seventeen subjects (Table 1) with a unilateral stroke participated in this study. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were ability to stand unassisted for 5 minutes, no major vertebral or lower extremity surgery/injury in the past year, and no history of fainting. Subjects were recruited at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (RIC) and Northwestern University. Experiments were conducted at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). All methods were approved by both RIC/Northwestern and UIC’s Institutional Review Boards. Subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Faller (n=10) mean (SE) or N |

Non-faller (n=7) mean (SE) or N |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Subject characteristics

| |||

| Gender (M/F) | 7/3 | 7/0 | |

| Age (year) | 61.7 (3.4) | 57.7 (2.5) | 0.4 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 29.2 (1.2) | 28.0 (2.4) | 0.62 |

| Hemiparetic side (R/L) | 8/2 | 5/2 | |

| Dominant leg before stroke (R/L/unknown) | 6/3/1 | 6/0/1 | |

| Time since stroke (year) | 9.8 (1.8) | 7.0 (1.2) | 0.27 |

| Stroke type (ischemic/hemorrhagic/unknown) | 6/4/0 | 5/1/1 | |

|

| |||

|

Clinical scores

| |||

| Berg balance | 47.7 (2.3) | 52.9 (1.1) | 0.09 |

| 5 time sit to stand (s) | 25.0 (4.1) | 22.1 (4.4) | 0.64 |

| 10 m walk (comfortable pace) (s) | 9.69 (2.8) | 6.8 (0.8) | 0.4 |

| 10 m walk (fast) (s) | 8.8 (3.8) | 5.0 (0.4) | 0.42 |

| PASE | 130.5 (18.7) | 156.2 (29.6) | 0.45 |

| Fear of falling | 30.1 (2.7) | 23.6 (2.5) | 0.11 |

| Asymmetry of stance | 1.16 (0.16) | 1.00 (0.08) | 0.44 |

Abbreviations: M male, F female, R right, L left

Subjects’ weight, height, leg dominance pre-stroke, stroke type/date, and affected limb were recorded. Clinical measures of balance were quantified using: Berg balance, 5 times sit-to-stand, 10m walk test (comfortable/fast). Questionnaires evaluating fall history, fear-of-falling, and physical activity (PASE: Physical activity Scale for the Elderly) were administered (Table 1).

Stance Asymmetry was measured while subjects stood at a self-selected stance width with feet on force plates (AMTI, Watertown, MA). The ratio of non-paretic leg vertical force to paretic leg vertical force was calculated.

Graded anteriorly- and posteriorly-directed perturbations intended to require a stepping response to avoid falling were delivered while subjects stood on a dual-belt, stepper motor driven treadmill (ActiveStepTM, Simbex, Lebanon, NH). Subjects wore a safety harness attached to a ceiling. This harness was adjusted to allowed the subject to fall in a natural, unobstructed way but safely prevented subjects’ hands and knees from contacting the treadmill following a failed recovery.

Perturbations were separated into pretest, training, and post-test phases. The pre- and post-tests consisted of the same six perturbations. Three anteriorly-directed perturbations and three posteriorly-directed perturbations of increasing difficulty were delivered. The magnitudes of the perturbations were a function of the displacement, velocity, and acceleration. The same perturbations were used for all subjects. Posteriorly-directed perturbations were designed to be large enough to evoke a forward step to avoid falling. The displacements, velocities and accelerations of these perturbations ranged from 0.22 – 0.76m, 0.26 – 1.3 m/s and 6.5 – 15.9 m/s2. Posteriorly-directed perturbations were classified by their level (1: small, 2: medium, 3: large). Anteriorly-directed perturbations, which required a backward step, were included to decrease anticipation of upcoming perturbation direction and not so large to evoke a fall. Therefore, all analyses described are for posterior-directed perturbations. Displacements, velocities and accelerations of anterior-directed perturbations ranged from 0.04 – 0.14m, −0.6 – −1.2 m/s and −10m/s2. The direction of the perturbation (anterior or posterior) was randomized but the magnitude of the perturbations proceeded from small (level 1) to large (level 3). Three subjects received only posteriorly-directed perturbations during the experiment; however two of these three subjects fell and it was considered important to include the data from these subjects. All pretest and post-test trials were included in the analysis.

Responses were classified as either a “Fall” or “Recovery”. A Fall was recorded if the subject became unambiguously supported by the safety harness. During the training portion of the protocol, 15 posteriorly-directed perturbations of a moderate magnitude (amplitude: 0.22m, velocity: 0.56m/s, acceleration: 13.89m/s2) were delivered.

Twenty-two passive-reflective markers were placed over landmarks on the upper and lower extremities and trunk using a modified Helen Hayes marker set (Kadaba, Ramakrishnan et al. 1990). The three-dimensional locations of the markers were recorded at 120Hz by an 8 camera motion capture system (Motion Analysis Co., Santa Rosa, CA) filtered using a 4th order Butterworth with a cutoff frequency 6Hz (Cortex 2.5.2, Motion Analysis Co., Santa Rosa, CA). A 12-segment rigid body model was constructed using the marker positions and kinematic variables were computed using custom software (MATLAB, Mathworks, Natick MA).

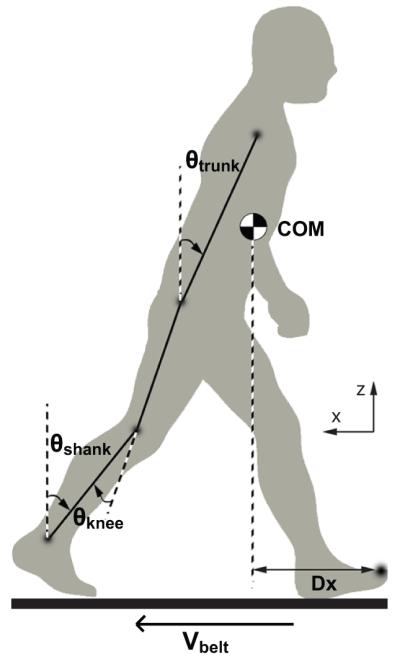

Analysis

The following dependent variables were used to evaluate the first recovery step following perturbation. The limb that performed the initial recovery step was referred to as the stepping limb while the contralateral limb was referred to as the base limb. Step_start refers to the first step initiation and step_end refers to the instant any part of the stepping foot (e.g. heel or toe) made contact with the treadmill belt. Step_start and step_end were quantified visually. Subject and trial type (fall vs recovery) were blinded to the reviewer.

Reaction time: time from perturbation onset (quantified by an automated program and verified through visual inspection of horizontal motion of the toe marker) to step_start

Step duration: time from step_start to step_end

Step length: sagittal plane distance between center of stepping foot and center of the base foot at step_end.

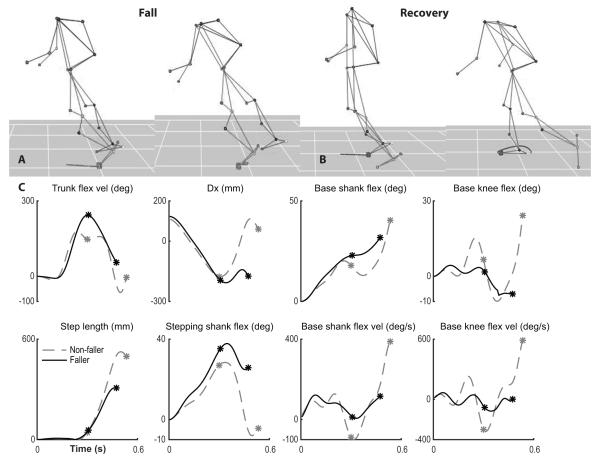

The following dependent variables were quantified at step_start and step_end relative to initial starting position (Figure 1).

Trunk flexion: sagittal plane angle of the line connecting the center of the pelvis to the midpoint of the line between the shoulder markers.

Shank flexion: sagittal plane angle of the line connecting the ankle joint center to the knee joint center.

Knee flexion: angle between the line connecting the knee joint center to the hip joint center and the line connecting the ankle joint center to the knee joint center.

Dx: sagittal plane distance between the vertical projection of center of mass (COM) to the edge base of support (stepping leg toe marker). A positive value indicated COM was within the boundary of the base of support. COM was calculated using marker positions (Orthotrak 5.0 reference manual) for each subject.

The time derivatives of the trunk, shank, knee flexion, and Dx time series were calculated to derive the velocity of each.

Figure 1. Kinematic definitions.

Figure depicts orientation of joint angles and Dx.

Our purpose was to establish the extent to which variables that distinguish successful and failed stepping responses by post-stroke patients differ from those previously described for unimpaired older adults. We hypothesized that metrics previously described to be important in older adults (e.g. trunk flexion velocity and recovery step length) would best characterize successful and failed recovery attempts. First, we compared trials where subjects fell (Fall) and trials where subjects did not fall (Recovery). We conducted a between-group (Fall vs. Recovery) comparison of the kinematic variables (Table 2). An ANOVA was performed using a linear mixed effects model with Fall and Recovery, and perturbation level (1-3) as the independent variables and kinematic variables (quantified at step_start and step_end) as the dependent variables. Subjects were treated as a random factor. Tukey honestly significant difference was used for all post-hoc comparisons.

Table 2.

Fall and Recovery trial comparison (level 3)

| variable | Fall (n=15) | Recovery (n=17) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

At Step Start (SS)

| |||

| Reaction time (s) | 0.266 (0.019) | 0.250 (0.018) | 0.64 |

| Trunk flexion (deg) | 17.9 (0.9) | 14.5 (0.9) | 0.42 |

| Trunk flexion velocity (deg/s) | 208.3 (7.3) | 205.1 (6.8) | 0.65 |

| Dx (mm) | −179.2 (9.3) | −145.5 (8.7) | 0.04 * |

| Vx (mm/s) | −644.0 (83.5) | −709.5 (78.3) | 0.91 |

| MOS (mm) | −385.7 (15.2) | −338.6 (14.2) | 0.09 |

| Stepping shank flexion (deg) | 27.0 (0.8) | 25.6 (0.7) | 0.20 |

| Stepping shank flexion velocity (deg/s) | 141.6 (11.0) | 175.5 (10.3) | 0.40 |

| Stepping knee flexion (deg) | 30.0 (1.9) | 28.7 (1.8) | 0.58 |

| Stepping knee flexion velocity (deg/s) | 402.5 (26.0) | 476.7 (24.4) | 0.31 |

| Base shank flexion (deg) | 17.9 (0.5) | 15.6 (0.5) | 0.69 |

| Base shank flexion velocity (deg/s) | 15.0 (5.8) | −15.6 (5.4) | 0.047 * |

| Base knee flexion (deg) | 2.5 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.2) | 0.12 |

| Base knee flexion velocity (deg/s) | −43.9 (12.8) | −102.6 (12.0) | 0.05 |

|

| |||

|

At Step End (SE)

| |||

| Step duration (s) | 0.195 (0.014) | 0.229 (0.013) | 0.09 |

| Step length (mm) | 367.8 (22.6) | 524.0 (21.2) | 0.0002 *** |

| Trunk flexion (deg) | 44.2 (1.7) | 41.7 (1.6) | 0.60 |

| Trunk flexion velocity (deg/s) | 42.5 (7.2) | −6.5 (6.7) | 0.0004 *** |

| Dx (mm) | −69.9 (17.9) | 83.3 (16.8) | 0.0001 *** |

| Vx (mm/s) | −1445.6 (38.8) | −1461.2 (36.4) | 0.78 |

| MOS (mm) | −486.7 (21.9) | −347.3 (20.5) | 0.0043 ** |

| Stepping shank flexion (deg) | 14.2 (1.2) | 4.6 (1.1) | 0.0005 *** |

| Stepping shank flexion velocity (deg/s) | 147.1 (9.0) | 171.5 (8.4) | 0.17 |

| Stepping knee flexion (deg) | 28.5 (1.4) | 25.9 (1.3) | 0.50 |

| Stepping knee flexion velocity (deg/s) | 61.9 (16.1) | 114.2 (15.1) | 0.12 |

| Base shank flexion (deg) | 28.2 (1.0) | 32.7 (0.9) | 0.0049 ** |

| Base shank flexion velocity (deg/s) | 128.2 (6.7) | 187.9 (6.3) | 0.0078 ** |

| Base knee flexion (deg) | −3.9 (1.6) | 7.6 (1.5) | ~0 *** |

| Base knee flexion velocity (deg/s) | 94.8 (16.7) | 246.9 (15.7) | ~0 *** |

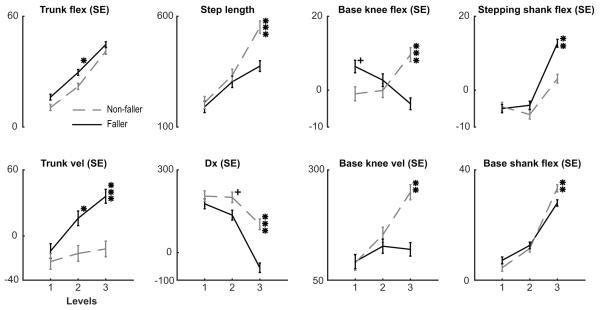

Second, we compared all trials (Fall and Recovery) for those subjects who fell (Fallers) compared to those who never fell (Non-Fallers). This analysis allows us to evaluate if Fallers respond differently to perturbations of any size regardless of if they fall. A between-group analysis of Fallers vs. Non-Fallers was conducted using a linear mixed effects ANOVA with perturbation level (1-3), and Faller/Non-Faller as independent variables and kinematic variables as the dependent variables.

Between-group comparisons (Fallers vs. Non-Fallers) for subject characteristics and clinical scores (Table 1) were conducted using independent t-tests. All statistics were evaluated using R (R Development Core Team, 2006). All statistical tests were made at a significance level of p < 0.05. All variances reported are standard errors.

RESULTS

Fallers and Non-fallers were not distinguished by the variables related to age, BMI, stroke, and performance on clinical tests. None of the between-group differences in these variables achieved significance (all p>0.05; Table 1).

The subjects characterized as Fallers (n=10) fell at least once and, as a group, registered 18 total falls. Fifteen of the falls occurred following level 3, the largest posteriorly-directed perturbation. Consequently, Fall and Recovery differences are reported for only level 3. Two subjects fell following the smallest perturbation (level 1) including one subject who fell twice and did not initiate a recovery step. For safety, the investigator elected not to have this subject complete level 2 and 3 perturbations.

Fall vs. Recovery

Two differences were found between Fall and Recovery trials at step_start (Table 1, Figure 2). Dx (P = 0.04) and base shank flexion velocity (P = 0.047). Dx was more negative in Fall trials such that center of mass was anterior to base of support indicating a less dynamically stable position at step_start when subjects fell. Base shank flexion velocity was more negative during Recovery trials indicating that the Base shank remained more vertical when subjects did not fall.

Figure 2. Fall vs. Recovery Kinematics.

A representative Fall (A) and Recovery (B) trial are shown at step_start (left) and step_end (right). Passive-reflective markers are joined together to show body movement. Dependent variables are depicted (C) for the Fall (solid black) and Recovery (dashed gray) trials. Stars mark step_start and step_end. The stepping leg’s toe marker is traced with a gray line from perturbation onset (left) and during the step (right).

Kinematic differences between Fall and Recovery trials at step_end parallel our previously published results for unimpaired older adults (Grabiner, Donovan et al. 2008). Fall trials were characterized by a shorter recovery step (Step length: P = 0.0002), a larger – less vertical – stepping shank flexion (P = 0.0005) indicating a less complete recovery step, and a negative Dx reflecting a center of mass positioned anteriorly to the base of support (P = 0.0001). Further a larger trunk flexion velocity (P = 0.0004) in Fall trials indicates subjects were able not able to reverse the direction of trunk motion by step_end.

There were also significant differences in the base limb (non-stepping limb) at step_end that occurs just before the base limb initiates a second recovery step. Base shank flexion and knee flexion, and associated velocities were larger during Recovery trials (all P < 0.0049) showing that the base knee was flexed and the shank less vertically-oriented at the end of the first step when subjects did not fall. Recovery trials showed increased movement of the base limb suggesting that the subject was preparing for a second step. No differences were found in reaction time and step duration (all P > 0.088) or in trunk and stepping knee flexion (all P > 0.49).

In almost all trials (90.5%), the non-paretic limb step was used for the first recovery step. Only 9 trials across all levels of perturbation demonstrated the paretic limb as the first recovery step. Two Fallers and one Non-Faller used the paretic limb as the first recovery step. The paretic limb was the dominant leg prior to stroke in 2 of the 3 subjects (1 Faller and 1 Non-Faller).

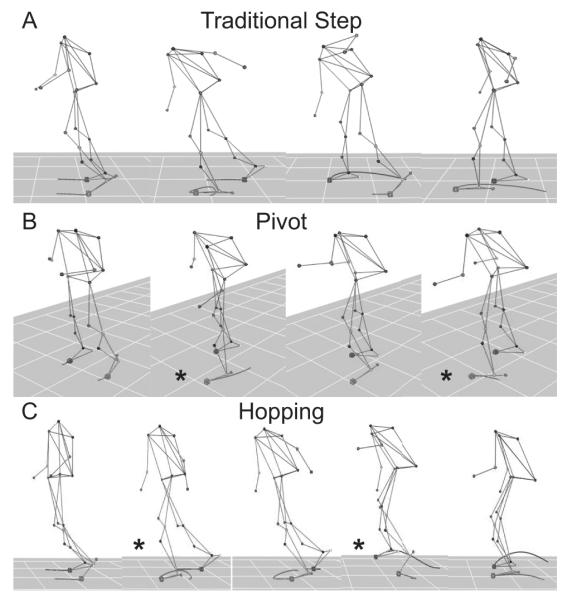

Compensatory strategies

Three types of recovery step strategies were observed in stroke survivors on level 3 perturbations: traditional compensatory step, pivot, and hopping (Figure 3). Nine subjects (6 Fallers and 3 Non-Fallers) consistently used the traditional compensatory step (Figure 3A) similar to that previously reported in unimpaired subjects and older adults (Maki and McIlroy 2006, Grabiner, Donovan et al. 2008, Crenshaw, Rosenblatt et al. 2012). Of the remaining subjects, five (3 Fallers and 2 Non-Fallers) used the pivot strategy (Figure 3B) at least once. The pivot strategy was stereotyped by a first recovery step taken by the non-paretic limb (left star). Next, instead of a second recovery step with the base, paretic limb, subjects performed a second recovery step with the non-paretic limb (right star). Subjects pivoted around the paretic limb such that subjects faced orthogonally to the direction of the initial perturbation. Four subjects (all Non-Fallers) used a hopping strategy (Figure 3C) at least once. Two subjects (Non-Fallers) used a hopping/pivot combination. The hopping strategy also began with a first recovery step with the non-paretic limb (left star). Next instead of a base, paretic limb second recovery step, subjects gained elevation in both legs by utilizing a bilateral hopping strategy (right star) i.e. the “second recovery step” involved both limbs.

Figure 3. Strategies.

Stroke survivors exhibited three strategies: traditional compensatory step (A), pivot (B) and hopping (C).

Fallers vs Non-Fallers

When Fallers were compared to Non-Fallers, between-group differences were similar to those during Fall and Recovery trials. While no clinical metrics were found to be different between Fallers and Non-Fallers (Table 1), level 3 kinematic differences were found in step length, base knee flexion, stepping shank flexion, trunk flexion velocity, Dx, base knee flexion velocity, and base shank flexion velocity (all P < 0.001)(Figure 4). Interestingly, trunk flexion, trunk flexion velocity were found to be different between Fallers and Non-Fallers on level 2 and Dx showed a trend towards significance indicating that Fallers and Non-Fallers react differently even on perturbations where neither population experienced a fall.

Figure 4. Faller vs. Non-Faller comparisons.

Fallers (solid black) and Non-Fallers (dashed gray) are compared across all levels of posterior-directed perturbations, level 1 is the smallest perturbation. + = P-value < 0.1; * = P-value < 0.05, ** = P-value < 0.01, *** = P-value < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to establish the extent to which variables that distinguish successful and failed stepping responses by individuals who have had a stroke differ from those previously described for unimpaired older adults. A key outcome was that the hypothesis that variables previously described to be important in older adults during the stepping response would best characterize successful and failed recovery attempts following a stroke was supported. Consistent with our previously findings for unimpaired older adults, we found that the ability to arrest and reverse trunk flexion and the length of the first recovery step were key characteristics associated with avoiding a fall. We also found that kinematics associated with preparation for a second step characterized Fallers and Fall trials. Finally, we identified 2 compensatory strategies (pivot, hopping) utilized by stroke survivors.

Most previous works have evaluated static balance, clinical metrics, and dynamic postural responses during small perturbations that were not intended to evoke a fall. In contrast, the present work focused on responses by stroke survivors to large balance challenges that required a stepping response to avoid a fall. To our knowledge, there have been only two other groups to evaluate laboratory-induced falls in stroke survivors (Marigold and Eng 2006, Kajrolkar, Yang et al. 2014, Salot, Patel et al. 2015). We expanded upon this work by being the first to 1) evaluate stroke survivors during falls that simulate tripping (forward stepping response) and 2) identify the unique compensatory strategies used by stroke survivors for fall avoidance.

The ability to arrest and reverse trunk flexion and execute a sufficiently long first step have previously been shown to be critical features in older neurologically unimpaired women, lower extremity amputees, and young adults (Grabiner, Donovan et al. 2008, Crenshaw, Rosenblatt et al. 2012, Weerdesteyn, Laing et al. 2012, Crenshaw, Kaufman et al. 2013). Therefore at the end of the first recovery step, stroke survivors are in a similar biomechanical situation as these other groups. This is not surprising given that most of the time (90.5%) they used their non-paretic limb for stepping. During large perturbations that require a second step, stroke survivors who showed preparation for a second step (larger base shank and knee flexion at recovery step completion) did not fall.

The pivot and hopping strategies utilized by stroke survivors appear to be adaptive strategies to account for the reduced ability to take a second step with the paretic limb. The pivot strategy is commonly expressed during asymmetrical gait (Forssberg, Grillner et al. 1980, Duysens, Potocanac et al. 2012). However, the hopping strategy appears the most effective and used exclusively by half of the Non-Fallers (4 out of 7). Lower-limb amputees also utilize a hopping strategy to avoid a Fall (Crenshaw, Kaufman et al. 2013). Lower-extremity amputees are able to learn and implement a stepping response following task-specific training (Crenshaw, Kaufman et al. 2013). It is less likely that stroke survivors will adopt a traditional compensatory stepping strategy with training given their neurological deficits; therefore, hopping may be a plausible strategy considered for this population. These represent hypotheses for future work.

Task specific training

Despite unique functional deficits in stroke survivors (Krakauer 2005, Sangani, Starsky et al. 2007, Handley, Medcalf et al. 2009, Langhorne, Coupar et al. 2009), our results suggest that they fall for similar biomechanical reasons as unimpaired individuals. While requiring replication, it indicates that stroke survivors may be amenable to similar training protocols that are effective in other populations. Task specific training decreases falls in older women and lower extremity amputees (Grabiner, Bareither et al. 2012, Crenshaw, Kaufman et al. 2013). Task specific training is a targeted approach that exposes subjects to potential falls in a safe, controlled environment, where injury is not likely, to improve stepping responses. Importantly, improvements achieved during training in one modality translate to different environments in which falls occur. Older women who received trip-specific training on a treadmill demonstrated significantly fewer falls following laboratory-induced over-ground trips (Grabiner, Bareither et al. 2012) and fewer trip-related falls measured prospectively in the community. There is evidence that stroke survivors respond well to task-specific training. Stroke survivors who have completed task-specific training programs targeting weight asymmetry and the use of the paretic limb during balance disturbances have shown marked improvements in these factors (Hocherman, Dickstein et al. 1984, Mansfield, Peters et al. 2010, Mansfield, Inness et al. 2011).

Predicting Fallers

The ability to accurately predict those at highest risk of falling in the community is a significant problem that has no clear answer (Tromp, Pluijm et al. 2001, Weerdesteyn, Niet et al. 2008, Divani, Majidi et al. 2011, Persson, Hansson et al. 2011, Simpson, Miller et al. 2011). We found numerous metrics during the largest perturbation that were different but exposing stroke survivors to large perturbations is not practical. However, Fallers and Non-Fallers show differences in trunk flexion and trunk flexion velocity during smaller level 2 perturbations with Dx trending towards significance (Figure 4). Evaluation of these metrics following small perturbations may be clinically accessible metric to predict fallers.

Future directions

The non-paretic limb dominated the first recovery step raising questions about how fall risk might change if the paretic limb was utilized. The fact that non-paretic limb stepping was initiated so often suggests that this has become the preferred and possibly automatic response for this population. The community environment will certainly elicit trips that necessitate a paretic limb recovery step, representing an important area for future study.

It remains unclear if future training strategies should encourage 1) paretic limb stepping 2) nonparetic limb stepping or 3) an approach that employs both. The second strategy may be less intuitive; however, it encourages use of the least impaired limb potentially giving the best chance of recovery. Not only is this limb stronger, when stroke survivors use the non-paretic limb for recovery, they perform in a manner that mirrors neurologically unimpaired individuals.

Weight bearing asymmetry (WBA) is known to impact postural stability (Kamphuis, de Kam et al. 2013, de Kam, Kamphuis et al. 2016). While, we report no differences between Fallers and Non-Fallers, our metric is incomplete taken only at one time point. Future work should evaluate WBA’s impact on successful recovery, strategy choice (e.g. pivot), and limb-choice (e.g. paretic stepping).

CONCLUSIONS

At the completion of the first recovery step following a large postural perturbation, the characteristics associated with a fall in stroke survivors are similar to those of neurologically intact populations. However stroke survivors struggle to initiate a second step with the paretic limb leading to adaptive, but not necessarily ideal strategies (e.g pivot) in an attempt to avoid a fall. Future work should evaluate task-specific training programs to enhance performance of the paretic limb and encourage successful adaptive strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R00 HD073240. In addition the authors would like to thank Noah Rosenblatt, PhD and Mackenzie Pater, PhD for their assistance with data collection and software programing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

University of Illinois at Chicago owns a patent on some technology used in the ActiveStep treadmill system and consequently there is an institutional conflict of interest.

Mark D. Grabiner is an inventor of the ActiveStep system but has no conflicts of interest to declare with regard to the present study.

REFERENCES

- Badke MB, Duncan PW. Patterns of rapid motor responses during postural adjustments when standing in healthy subjects and hemiplegic patients. Phys Ther. 1983;63(1):13–20. doi: 10.1093/ptj/63.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw JR, Kaufman KR, Grabiner MD. Compensatory-step training of healthy, mobile people with unilateral, transfemoral or knee disarticulation amputations: A potential intervention for trip-related falls. Gait Posture. 2013;38(3):500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw JR, Kaufman KR, Grabiner MD. Trip recoveries of people with unilateral, transfemoral or knee disarticulation amputations: Initial findings. Gait Posture. 2013;38(3):534–536. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw JR, Rosenblatt NJ, Hurt CP, Grabiner MD. The discriminant capabilities of stability measures, trunk kinematics, and step kinematics in classifying successful and failed compensatory stepping responses by young adults. J Biomech. 2012;45(1):129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kam D, Kamphuis JF, Weerdesteyn V, Geurts AC. The effect of weight-bearing asymmetry on dynamic postural stability in healthy young individuals. Gait Posture. 2016;45:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio RP. Lower extremity antagonist muscle response following standing perturbation in subjects with cerebrovascular disease. Brain Res. 1987;406(1-2):43–51. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90767-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener HC, Ackermann H, Dichgans J, Guschlbauer B. Medium- and long-latency responses to displacements of the ankle joint in patients with spinal and central lesions. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1985;60(5):407–416. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(85)91014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener HC, Dichgans J, Guschlbauer B, Mau H. The significance of proprioception on postural stabilization as assessed by ischemia. Brain research. 1984;296:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90515-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Berger W. Interlimb coordination of posture in patients with spastic paresis. Impaired function of spinal reflexes. Brain. 1984;107:965–978. doi: 10.1093/brain/107.3.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divani A. a., Majidi S, Barrett AM, Noorbaloochi S, Luft AR. Consequences of Stroke in Community-Dwelling Elderly: The Health and Retirement Study, 1998 to 2008. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2011 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.607630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duysens J, Potocanac Z, Hegeman J, Verschueren S, McFadyen BJ. Split-second decisions on a split belt: does simulated limping affect obstacle avoidance? Exp Brain Res. 2012;223(1):33–42. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forssberg H, Grillner S, Halbertsma J, Rossignol S. The locomotion of the low spinal cat. II. Interlimb coordination. Acta Physiol Scand. 1980;108(3):283–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1980.tb06534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabiner MD, Bareither ML, Gatts S, Marone J, Troy KL. Task-Specific Training Reduces Trip-Related Fall Risk in Women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318268c89f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabiner MD, Donovan S, Bareither ML, Marone JR, Hamstra-Wright K, Gatts S, Troy KL. Trunk kinematics and fall risk of older adults: translating biomechanical results to the clinic. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2008;18(2):197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley A, Medcalf P, Hellier K, Dutta D. Movement disorders after stroke. Age and ageing. 2009;38:260–266. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocherman S, Dickstein R, Pillar T. Platform training and postural stability in hemiplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1984;65(10):588–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikai T, Kamikubo T, Takehara I, Nishi M, Miyano S. Dynamic postural control in patients with hemiparesis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82(6):463–469. quiz 470-462, 484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadaba MP, Ramakrishnan HK, Wootten ME. Measurement of lower extremity kinematics during level walking. J Orthop Res. 1990;8(3):383–392. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajrolkar T, Yang F, Pai YC, Bhatt T. Dynamic stability and compensatory stepping responses during anterior gait-slip perturbations in people with chronic hemiparetic stroke. J Biomech. 2014;47(11):2751–2758. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis JF, de Kam D, Geurts AC, Weerdesteyn V. Is weight-bearing asymmetry associated with postural instability after stroke? A systematic review. Stroke Res Treat. 2013;2013:692137. doi: 10.1155/2013/692137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer JW. Arm function after stroke: from physiology to recovery. Seminars in neurology. 2005;25:384–395. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-923533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhorne P, Coupar F, Pollock A. Motor recovery after stroke: a systematic review. Lancet neurology. 2009;8:741–754. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki BE, McIlroy WE. Control of rapid limb movements for balance recovery: age-related changes and implications for fall prevention. Age and ageing. 2006;35(Suppl 2):ii12–ii18. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield A, Inness EL, Komar J, Biasin L, Brunton K, Lakhani B, Mcilroy WE. Training Rapid Stepping Respopnses in an Individual With Stroke. Physical Therapy. 2011;91 doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield A, Maki BE. Are age-related impairments in change-in-support balance reactions dependent on the method of balance perturbation? Journal of biomechanics. 2009;42:1023–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield A, Peters AL, Liu BA, Maki BE. Effect of a Perturbation-Based Balance Stepping and Grasping Reactions in Older Adults : A Randomized. Physical Therapy. 2010;90 doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marigold DS, Eng JJ. Altered timing of postural reflexes contributes to falling in persons with chronic stroke. Experimental brain research. Experimentelle Hirnforschung. Expérimentation cérébrale. 2006;171:459–468. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0293-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marigold DS, Eng JJ, Inglis J. Timothy. Modulation of ankle muscle postural reflexes in stroke: influence of weight-bearing load. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115(12):2789–2797. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marigold DS, Eng JJ, Tokuno CD, Donnelly CA. Contribution of muscle strength and integration of afferent input to postural instability in persons with stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2004;18(4):222–229. doi: 10.1177/1545968304271171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson CU, Hansson P-O, Sunnerhagen KS. Clinical tests performed in acute stroke identify the risk of falling during the first year: postural stroke study in Gothenburg (POSTGOT) Journal of rehabilitation medicine : official journal of the UEMS European Board of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2011;43:348–353. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salot P, Patel P, Bhatt T. Reactive Balance in Individuals With Chronic Stroke: Biomechanical Factors Related to Perturbation-Induced Backward Falling. Phys Ther. 2015 doi: 10.2522/ptj.20150197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangani SG, Starsky AJ, McGuire JR, Schmit BD. Multijoint reflexes of the stroke arm: neural coupling of the elbow and shoulder. Muscle & nerve. 2007;36:694–703. doi: 10.1002/mus.20852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L. a., Miller WC, Eng JJ. Effect of Stroke on Fall Rate, Location and Predictors: A Prospective Comparison of Older Adults with and without Stroke. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tromp AM, Pluijm SM, Smit JH, Deeg DJ, Bouter LM, Lips P. Fall-risk screening test: a prospective study on predictors for falls in community-dwelling elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(8):837–844. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00349-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerdesteyn V, Laing AC, Robinovitch SN. The body configuration at step contact critically determines the successfulness of balance recovery in response to large backward perturbations. Gait Posture. 2012;35(3):462–466. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerdesteyn V, Niet MD, Duijnhoven HJRV, Geurts ACH. Falls in individuals with stroke. interactions. 2008;45:1195–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]