Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: biliary atresia, biliary development, liver development

ABSTRACT

Objectives:

Biliary atresia (BA) is a progressive fibroinflammatory cholangiopathy affecting the bile ducts of neonates. Although BA is the leading indication for pediatric liver transplantation, the etiology remains elusive. Adducin 3 (ADD3) and X-prolyl aminopeptidase 1 (XPNPEP1) are 2 genes previously identified in genome-wide association studies as potential BA susceptibility genes. Using zebrafish, we investigated the importance of ADD3 and XPNPEP1 in functional studies.

Methods:

To determine whether loss of either gene leads to biliary defects, we performed morpholino antisense oligonucleotide (MO) knockdown studies targeting add3a and xpnpep1 in zebrafish. Individuals were assessed for decreases in biliary function and the presence of biliary defects. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed on pooled 5 days postfertilization larvae to assess variations in transcriptional expression of genes of interest.

Results:

Although both xpnpep1 and add3a are expressed in the developing zebrafish liver, only knockdown of add3a produced intrahepatic defects and decreased biliary function. Similar results were observed in homozygous add3a mutants. MO-mediated knockdown of add3a also showed higher mRNA expression of hedgehog (Hh) targets. Inhibition of Hh signaling rescued biliary defects caused by add3a knockdown. Combined knockdown of add3a and glypican-1 (gpc1), another mediator of Hh activity that is also a BA susceptibility gene, resulted in more severe biliary defects than knockdown of either alone.

Conclusions:

Our results support previous studies identifying ADD3 as a putative genetic risk factor for BA susceptibility. Our results also provide evidence that add3a may be affecting the Hh pathway, an important factor in BA pathogenesis.

What Is Known

The etiology of biliary atresia is unknown, but evidence suggests that genetic susceptibility may play a role.

A genome-wide association study identified a biliary atresia susceptibility locus on chromosome 10q24.2, in close proximity to the add3 and xpnpep1 genes.

What Is New

Loss of the zebrafish ortholog add3a, but not xpnpep1, leads to intrahepatic defects and impaired biliary function.

add3a morphants show upregulation of hedgehog pathway target genes, and inhibition of hedgehog rescues the phenotype.

Combined knockdown of add3a and gpc1, another known biliary atresia susceptibility gene, results in a more severe phenotype, indicating that these 2 genes may act within the same pathway.

Functional studies of candidate biliary atresia susceptibility genes can shed light on possible mechanisms of injury and pathogenesis of disease and biliary development.

Biliary atresia (BA) is an idiopathic, progressive, fibroinflammatory cholangiopathy that occurs exclusively in neonates. The incidence of BA ranges from 1 per 10,000 in the United States to up to 3.7 per 10,000 in parts of Asia (1,2). Until the advent of the Kasai hepatoportoenterostomy, BA was universally fatal. BA, however, continues to be the leading indication for pediatric liver transplantation worldwide.

Although the etiology of BA is unknown, it appears to be at least partially related to genetic factors affecting biliary development, as it presents exclusively in neonates and infants (3). Although BA is unlikely to be strictly a genetic disease, several studies have identified specific genes associated with BA (4). Recently, investigators using genome-wide association studies (GWASs) reported significant association with the chromosomal region around 10q24.2 for BA susceptibility in Asian (5,6) and Caucasian-American (7) populations. This region overlaps with the X-prolyl aminopeptidase 1 (XPNPEP1) and gamma-adducin (ADD3) genes (8). XPNPEP1 is found in hepatobiliary epithelial cells and encodes an enzyme that promotes the degradation of bradykinin and substance P (7,9), bioactive peptides involved in inflammation (10). Substance P also has an anticholeretic effect on hepatic bile flow (11) and is elevated in the serum of patients with cholestatic liver disease (12). ADD3 belongs to a family of actin cytoskeletal proteins involved in cell-cell contact in epithelial tissues (13). ADD3 is also abundantly expressed in the biliary tract of the fetal liver (14). Thus, both ADD3 and XPNPEP1 appear to be reasonable candidates for mediating BA susceptibility, because they are expressed in the liver and both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, and are important in pathways thought to be involved in BA pathogenesis and hepatobiliary development.

In the present study, we used zebrafish models to determine whether add3a or xpnpep1, the zebrafish homologs of human ADD3 and XPNPEP1, has functional roles in biliary development. Although both add3a and xpnpep1 are expressed in the developing zebrafish liver, we show that only a loss of add3a expression leads to decreased biliary function and biliary defects. We show that inhibition of hedgehog (Hh) signaling rescues biliary defects induced by add3a knockdown, suggesting that add3a may have a role in the Hh pathway. Interestingly, combined knockdown of add3a and gpc1, a gene we previously reported as involved in BA pathogenesis by upregulating Hh signaling (15), has an epistatic effect on biliary development. Our findings support and further the GWAS by demonstrating that ADD3, not XPNPEP1, is the most likely gene influencing BA susceptibility, and in addition we provide evidence suggesting a possible pathogenic mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Zebrafish Lines

Add3a knockdown experiments were performed on wild-type Tupfel long fin zebrafish embryos, raised in the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia animal facility according to approved protocols. Zebrafish embryos carrying a mutation in add3a, designated sa819, were obtained from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (ZIRC) and raised and bred in the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia animal facility as mentioned above. The sa819 fish carry a point mutation in the add3a gene that leads to a nonsense mutation (ZIRC). Homozygous mutants were determined by the appearance of heart edema at 2 days post fertilization (2 dpf), and the presence of the T>A change in individuals bearing the phenotype was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers used for Sanger sequencing are listed in Supplemental Digital Content, Table 1. All procedures involving zebrafish were conducted in accordance with federal guidelines and approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols. All animals received humane care according to the criteria outlined in the “Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.”

In Situ Hybridization Studies

PCR primers (Supplemental Digital Content, Table 1) were used to design antisense riboprobes for zebrafish add3 and xpnpep orthologs. Complementary DNA (cDNA) templates for xpnpep1, xpnpep2, add1, add2, add3a, and add3b were obtained using a T3 promoter sequence starting at the 5’ end of the reverse primer, as shown in the sequences in Supplemental Digital Content, Table 1. Treated larvae were sacrificed at 3 dpf then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. To remove pigmentation, fixed specimens were bleached in a solution containing 3% hydrogen peroxide and 1% potassium hydroxide, in accordance with standard protocols. In situ hybridization was performed on specimens as previously described (16).

Morpholino Antisense Oligonucleotide Design and Injection

Morpholino antisense oligonucleotides (MO) designed to target either add3a or xpnpep1 were obtained from GeneTools (Philomath, OR). Targeted sequences for blocking either a 5’ translational start site or a splice acceptor site are shown in Supplemental Digital Content, Table 1. Approximately 1.5 ng of morpholino was injected in embryos ranging from 1 to 8 cell stage and subsequently titrated to establish experimental dose. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis on cDNA derived from morpholino-injected larvae from either add3a or xpnpep1 was performed to confirm knockdown of spliced mRNA (Supplemental Digital Content, Fig. 1). Specificity of add3a MO−mediated knockdown was confirmed by rescuing the phenotype with injection of add3a mRNA (Supplemental Digital Content, Fig. 1) synthesized from a full-length add3a template construct (Addgene, Cambridge, MA) using mMessage mMachine (Ambion, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

For the add3a and gpc1 epistatic studies, add3a and gpc1 morpholinos were titrated so that individual low-dose concentrations did not produce significant impairment of biliary excretion, as assessed by gallbladder uptake of the quenched fluorescent phospholipid PED6. Morpholinos were combined so that individual low-dose concentrations were consistent with individual morpholino concentrations and injected into embryos between the 1–8 cell stage. Oligonucleotide sequences for gpc1 appeared previously in Cui et al (15). For the Hh pathway inhibition studies, larvae were incubated in E3 containing cyclopamine at a final concentration of 10 μmol/L from 2 dpf to 5 dpf.

PED6 Treatment

The quenched fluorescent phospholipid, PED6, was added to the water of 5 dpf embryos at a concentration of 0.1 μg/mL to allow direct visualization of the gallbladder (17). For morpholino-injected and mutant fish, PED6 uptake in the gallbladders was scored blindly as “normal,” “faint,” or “absent,” as in previous studies (18,19).

Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence

To study biliary anatomy, 5 dpf larval livers were stained for cytokeratin, allowing visualization of intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts, as in several previous studies (20). Immunostained livers were examined using confocal microscopy, and images were processed using ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop, as previously described.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction Studies of Gene Expression

qPCR was used to examine gene expression differences in the biliary transcription factor vhnf1, Notch target her6, Hh effector gli2a, and transforming growth factor beta 1β target connective tissue growth factor (ctgf). Other Hh targets that were used included ptch1, foxl1, znf697, and ccnd1. These primer sequences, including the normalizing primer pair for hprt, have been reported previously (15). For these studies, 5 dpf larvae were sacrificed and then stored in RNA later (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Per standard protocols, RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed to generate cDNA (Ambion, Invitrogen). qPCR was performed as in our previous studies on an Applied Biosystems StepOne Plus qPCR machine and software (15) using Perfecta-SYBR-green Fastmix (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD).

Statistical Tests

For comparison of the levels of PED6 uptake between groups, we used chi-square analysis similar to our previous studies (19). For the qPCR studies, Microsoft Excel was used to perform Student t test comparing groups, which were triplicate specimens, similar to previous studies (15).

RESULTS

Expression of add3a and xpnpep1 in Developing Liver

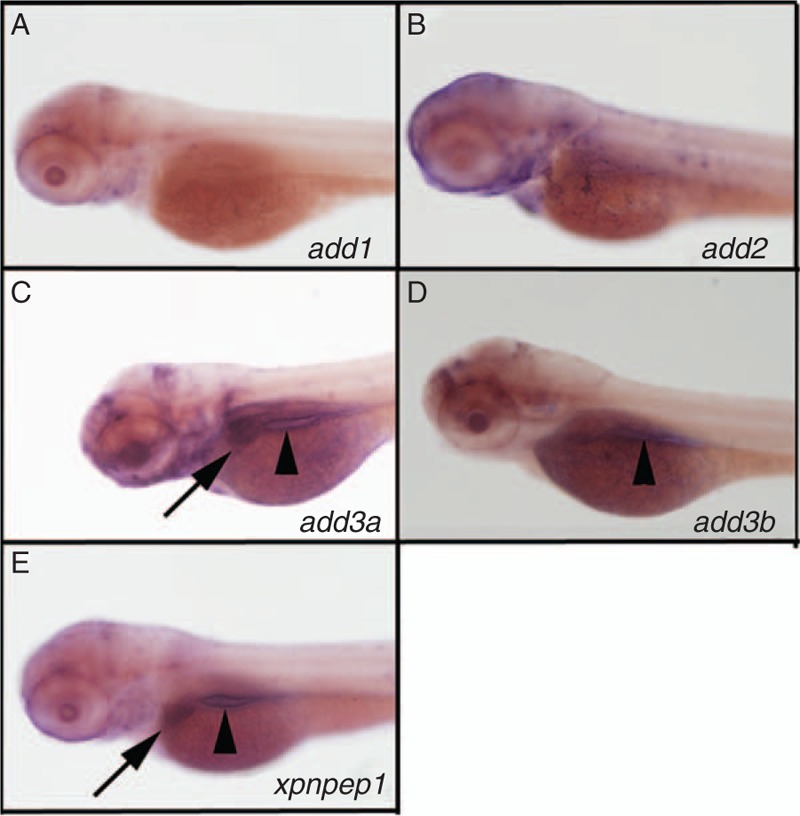

Genes of interest add3a and xpnpep1 are found on zebrafish chromosome 22 and are syntenic to their human counterparts, although they are not directly adjacent in zebrafish (www.ensembl.org, Zv9). These findings suggest that zebrafish add3a and xpnpep1 are orthologous to the human genes. Nevertheless, we examined members of the add3 and xpnpep families for liver expression during biliary development, because there are several possible orthologs for add3 and xpnpep1 in the fish. Both add3a (Fig. 1C) and xpenpep1 (Fig. 1E) showed expression in the developing liver. Thus, we chose to inhibit add3a and xpnpep1 to determine whether loss would lead to biliary defects and activation of pathways similar to those observed in BA.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of add3a and xpnpep1 in the developing liver. Whole-mount in situ hybridization (ISH) of 3 days post fertilization (dpf) zebrafish larvae probed for add1 (A), add2 (B), add3a (C), add3b (D), and xpnpep1 (E). There is liver staining for add3a (C, black arrow) and xpnpep1 (E, black arrow) but not for the other probes. There is intestinal staining for add3a, add3b and xpnpep1 (black arrowheads in C, D, E). There is also staining of add2 and add3a in the head region, which is of unclear specificity (B, C). Similar experiments were performed using a riboprobe directed against xpnpep2, but there was no staining in 3 dpf larvae (not shown).

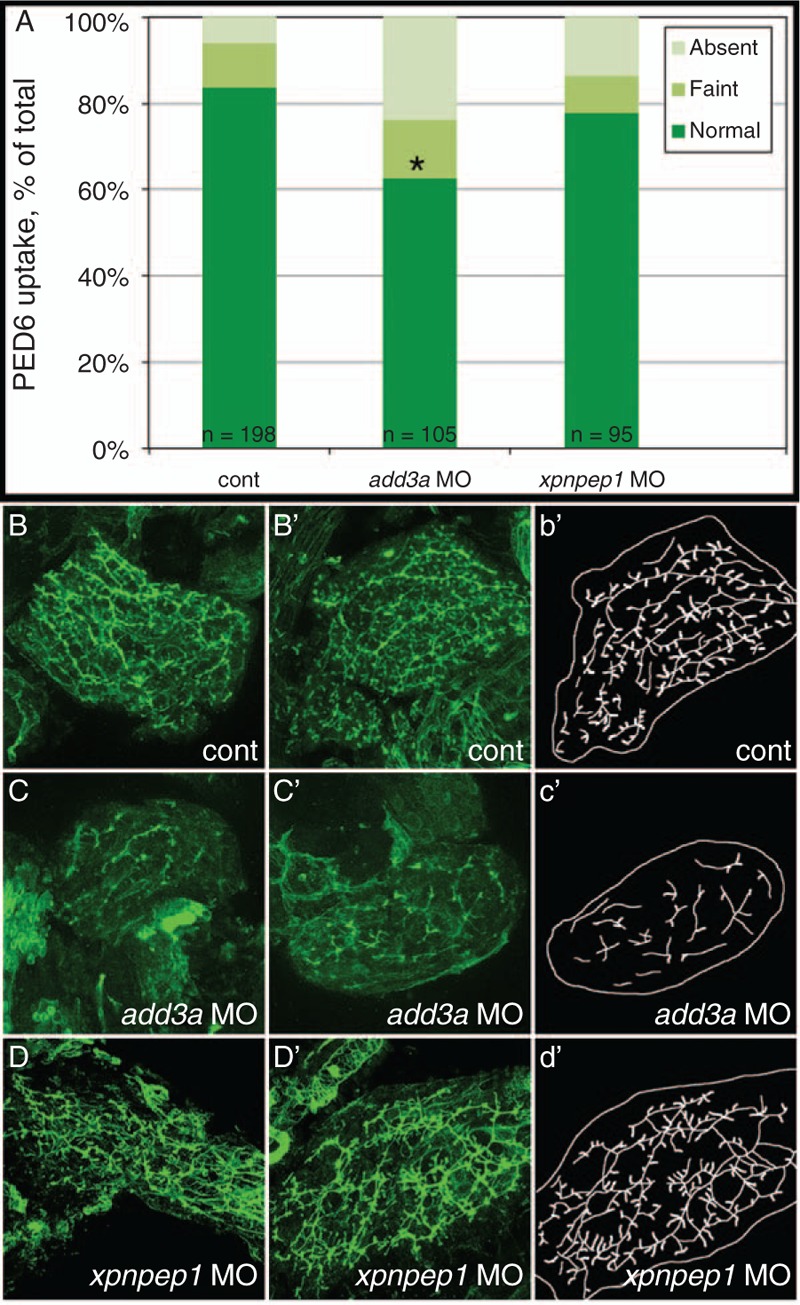

Knockdown of add3a, Not xpnpep1, Leads to Biliary Defects

To determine whether add3a and/or xpnpep1 have a functional role in mediating biliary defects, we used MO knockdown to reduce expression of the mature mRNA and decrease protein expression (15). Although add3a morphants showed decreased biliary function as measured by PED6 uptake (Fig. 2A), xpnpep1 knockdown had no significant effect on function (Fig. 2A). Cytokeratin staining showed obvious biliary abnormalities in the add3a morphants (Fig. 2C and C’), although xpnpep1 knockdown had only a minor effect on biliary morphology (Fig. 2D and D’) when compared to controls (Fig. 2B and B’). In addition, MO-mediated knockdown of add3a phenocopies genetic deficiency (Supplemental Digital Content, Fig. 2), as sa819 mutants demonstrate impaired biliary function (Supplemental Digital Content, Fig. 2B and C) and intrahepatic defects (Supplemental Digital Content, Fig. 2E and F), similar to morpholino-mediated knockdown. These results indicate add3a insufficiency, not xpnpep1, can result in biliary disease.

FIGURE 2.

Decreased biliary function and developmental biliary abnormalities in add3a morpholino-injected 5 days post fertilization (dpf) larvae. Wild-type fertilized oocytes were injected with MO directed against add3a or xpnpep1, or control. At 5 dpf, larvae were incubated in the fluorescent lipid PED6 and assayed for gallbladder uptake, and then fixed and stained for cytokeratin to document biliary anatomy. A, Percentages of control (cont), add3a MO-injected and xpnpep1 MO-injected larvae with normal, faint, or absent gallbladder visibility, reflecting PED6 uptake and thus biliary function. There is a significant decrease in biliary function in the add3a MO-injected larvae (∗P ≤ 0.0001 by chi-square analysis), whereas the difference between control and xpnpep1 MO-injected larvae is not significant. B, Confocal projections of cytokeratin immunostainings of livers from 5 dpf larvae injected with control (cont, B), add3a MO (C), or xpnpep1 MO (D). There are 2 examples of each condition (B, B’; C, C’; D, D’), and a schematic outline of each second example (b’, c’, d’). Note that the pattern of the intrahepatic ducts from the cont and xpnpep1 MO-injected larvae appears similar, whereas the add3a MO-injected larvae have shorter and sparser ducts. Original magnification ×400. MO = morpholino antisense oligonucleotide.

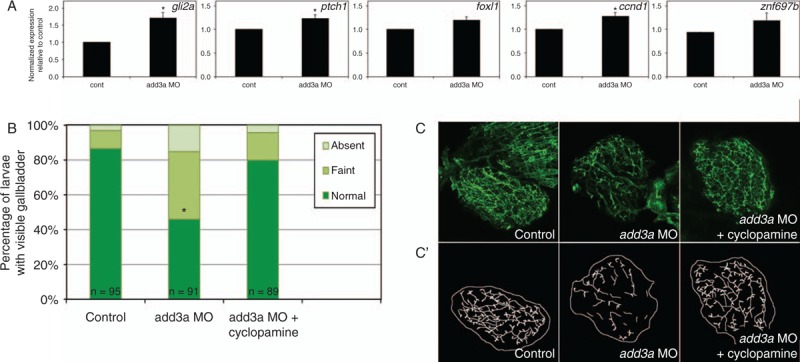

Knockdown of add3a Leads to Hedgehog Activation

We have previously demonstrated that GPC1, which encodes glypican-1, is a BA susceptibility gene. MO-mediated knockdown of gpc1 led to biliary defects similar to those shown here with add3a knockdown, and were associated with increased Hh activity (15). Hh activation is closely linked to liver fibrosis (21) and to BA (22), and thus we hypothesized that add3a deficits may also lead to increased Hh activity. To determine whether add3a was also affecting Hh activity, we examined transcriptional expression of Hh targets in add3a morphants.

Consistent with an increase in Hh pathway activity, add3a morphants showed increased expression of Hh target genes. Significant increases in expression were seen for gli2a, ptch1, and ccnd1 (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, similar qPCR analysis of other genes important in biliary development and disease such as the Notch signaling pathway and Hnf6/Hnf1β did not demonstrate changes in expression (Supplemental Digital Content, Table 2). These results suggest add3a knockdown may specifically affect Hh pathway activity.

FIGURE 3.

Studies of the Hedgehog (Hh) pathway in add3a morpholino-injected larvae. A, Quantitative RT-PCR of Hh pathway targets in control (cont) or add3a MO-injected larvae at 5 days post fertilization (dpf). Note that there is an increase in expression of all 5 genes shown (gli2a, ptch1, foxl1, ccnd1, znf697b), although only gli2a, ptch1, and ccnd1 demonstrate a significant difference (∗P ≤ 0.05 by Student t test). B, C, Cyclopamine treatment rescues biliary defects in add3a morpholino-injected larvae. Wild-type fertilized oocytes were injected with MO directed against add3a or control. At 2 dpf, cyclopamine or vehicle was added, and at 5 dpf, larvae were incubated in the fluorescent lipid PED6 and assayed for gallbladder uptake, and then fixed and stained for cytokeratin to document biliary anatomy. B, Percentages of control (cont), and vehicle or cyclopamine-treated add3a MO-injected larvae with normal, faint, or absent gallbladder visibility, reflecting PED6 uptake and thus biliary function. There is a significant decrease in biliary function in the add3a MO-injected larvae (∗P ≤ 0.0001 by chi-square testing), which is significantly different from the cyclopamine treated larvae, with the same p-value. C, Confocal projections of cytokeratin immunostainings of livers from 5 dpf larvae injected with control, add3a MO, or add3a MO with cyclopamine. C’) Schematic tracings of the cytokeratin stainings shown in (C). Original magnification ×400. MO = morpholino antisense oligonucleotide.

Inhibition of the Hedgehog Pathway Protects Against Biliary Defects

Quantitative analyses indicated that Hh transcriptional activity was higher in add3a morphants, suggesting that the biliary defects in add3a morphants could be related to Hh overactivity. To determine whether Hh overexpression has a role in the biliary defects, we inhibited the Hh pathway using the Hh receptor antagonist, cyclopamine, in add3a morphants. Incubation of add3a morphants with cyclopamine resulted in normalization of biliary function as measured by PED6 uptake comparable to control animals (Fig. 3B), and a morphological rescue of the biliary defects (Fig. 3C). These results again support the hypothesis that biliary defects observed in add3a are caused by Hh pathway overexpression.

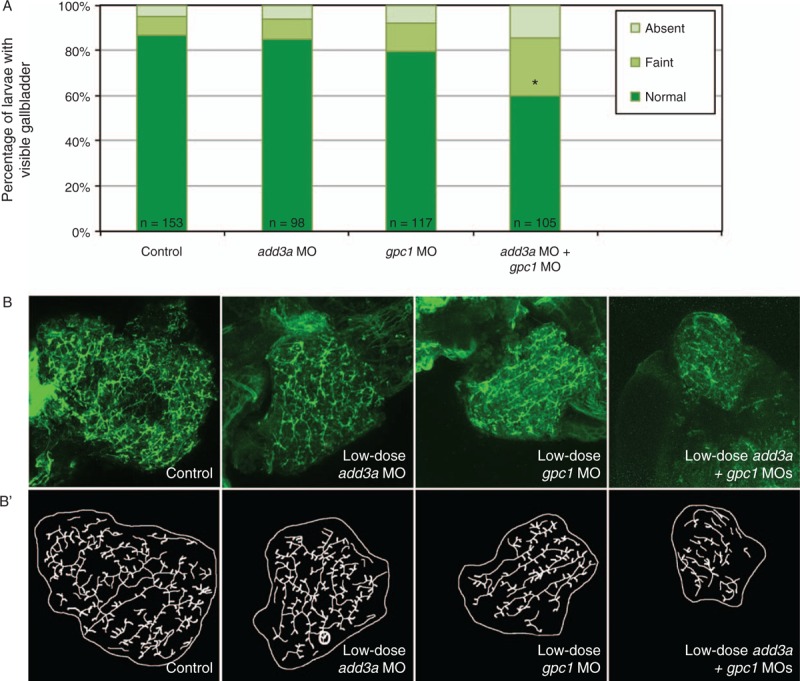

The add3a and gpc1 Genes Share Functional Characteristics in Mediating Biliary Development

We have previously used coinjection of MOs directed against targets in the same pathway to demonstrate an epistatic effect, supporting a combinatorial effect for the 2 genes (23). Because both add3a and gpc1 knockdown lead to biliary defects and Hh activation, we hypothesized that add3a and gpc1 function together to mediate biliary defects. Combined MO-mediated knockdown of add3a and gpc1 led to decreased biliary function and to biliary defects at doses that did not lead to abnormalities when injected alone (Fig. 4). These results support that add3a and gpc1 can work synergistically in the Hh pathway to mediate biliary defects.

FIGURE 4.

Epistatic effect of coinjection of add3a and gpc1 morpholinos on biliary function and development. Wild-type fertilized oocytes were injected with MO directed against add3a or gpc1 at lower amounts needed to see an effect, or control. At 5 days post fertilization (dpf), larvae were incubated in the fluorescent lipid PED6 and assayed for gallbladder uptake, and then fixed and stained for cytokeratin to document biliary anatomy. A, Percentages of control (cont), low-dose add3a MO-injected, low-dose gpc1 MO-injected, or add3a and gpc1 MO-injected larvae with normal, faint, or absent gallbladder visibility, reflecting PED6 uptake and thus biliary function. There is a significant decrease in biliary function only in the larvae injected with the lower dose of both MOs (∗P ≤ 0.0001 by chi-square analysis). B, Confocal projections of cytokeratin immunostainings of livers from 5 dpf larvae injected with control (cont), low-dose add3a MO, low-dose gpc1 MO, or the combination of both MOs at the lower dose. B’, Schematics of the respective panels shown in (B). Note that the intrahepatic duct pattern is similar in the control and the larvae injected with add3a or gpc1 MO alone, but that when the MOs are injected together the pattern is abnormal, with decreased duct density and complexity. Original magnification ×400. MO = morpholino antisense oligonucleotide.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that ADD3, not XPNPEP1, is a putative candidate susceptibility gene for BA. Using zebrafish, we show that MO-mediated knockdown of add3a leads to impaired biliary function and developmental biliary anomalies. Zebrafish with mutations in add3a has similar biliary developmental defects. Knockdown of add3a leads to activation of Hh signaling, and the biliary defects are reversed by inhibition of Hh signaling. Zebrafish injected with morpholinos against gpc1, which was identified as a candidate susceptibility gene in a study of copy number variation in patients with BA (24), demonstrate similar features to the add3a knockdown and mutant embryos. Moreover, add3a and gpc1 knockdown work additively in mediating biliary defects. Thus, like GPC1, ADD3 appears to be a BA susceptibility gene that may function through modulating Hh signaling.

Biliary Atresia Susceptibility Locus on Chromosome 10q24.2

In 2010, a genome wide association study performed in a Chinese population identified a BA susceptibility locus on chromosome 10q24.2 with a P value of 6.94 × 10–9(5). The most significant single nucleotide polymorphism was located between 2 genes, XPNPEP1 and ADD3. This finding was later replicated in a Caucasian population, with the strongest signal in intron 1 of the ADD3 gene (7). In that study, ADD3 protein was localized to intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts, and ADD3 gene expression was increased overall in BA liver as compared with normal control liver. In light of the specific localization of ADD3 to bile ducts, it is possible that the increased ADD3 expression in whole BA liver may be explained by bile ductular proliferation in these samples. A correlation between single nucleotide polymorphism genotype and ADD3 expression level was not identified in a small number of samples in that study (7). In 2013, Cheng et al (25) reported an exhaustive analysis of the 10q24.2 chromosomal region, in which they demonstrated a correlation between the risk allele and reduced expression of ADD3 specifically in BA liver. No such correlation was found for XPNPEP1. They also noted higher levels of ADD3 expression in liver obtained at the time of transplantation as compared with samples collected at time of Kasai, indicating that stage of disease may play a role. Taken together, the data suggest that the risk allele identified in the GWAS may result in a modest decrease in ADD3 gene expression in BA liver, but further studies will be required to determine the downstream effects of altered ADD3 expression at specific stages of development and disease progression.

Adducin Abnormalities and Biliary Defects

ADD3 encodes gamma-adducin, which forms tetramers at actin-spectrin junctions and interacts with calmodulin and gelsolin to tether the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane. Adducin is also important in cell movement, in the outgrowth of neurites, in the stabilization of epithelial junctions, and in the regulation of cell adhesion and cell polarity (26). In addition to other interactions, the adducin tetramer acts as a substrate for Rho-dependent kinases. Rho kinases are key regulators of cell contraction, migration, and cell polarity (27), and the phosphorylation of adducin by Rho-kinase promotes actin binding (28).

Normal epithelial polarity is essential for normal liver and biliary development (29,30). Hepatocyte polarity is lost in cholestatic liver injury, leading to further dysregulation of bile transport pathways (29,31). Interestingly, disruption of the actin cytoskeleton has been shown to induce cholestasis, because rats treated with phalloidin have decreased bile flow. There is altered hepatocyte polarity in these animals, as evidenced by disordered trafficking of canalicular proteins to the basolateral domain and vice versa (32,33). We have previously shown that disruption of planar cell polarity can lead to biliary defects, and these defects are in fact synergistic with inhibition of the actin cytoskeleton (19). Genetic disruption of adducin function could impair hepatocyte or cholangiocyte polarity and/or movement, which would then have an effect on bile duct development.

As noted above, we detected modest activation of Hh pathway targets in our add3a morphants, similar to what was observed in BA and in other cholestatic disorders (22), and inhibition of the Hh pathway rescued the add3a phenotype in zebrafish. Interestingly, actin-mediated cellular changes affect Hh signaling (34), and Hh signaling is also necessary for the stabilization of the actin cytoskeleton and tight junctions (35). Thus, disruption of add3 could lead to poor epithelial connections, disorganized actin cytoskeleton, and a loss of cell polarity that results in activation of Hh, which then leads to inflammation, fibrogenesis, and perhaps developmental biliary defects that perpetuate a cycle of Hh activation.

Assimilating Biliary Atresia Genetic Risk

The etiology of BA is most likely multifactorial, with environmental triggers such as toxins and infections combined with inflammatory and genetic risk factors (36). For example, the risk haplotype associated with ADD3 on chromosome 10q24.2 is relatively common, occurring in 49% of Chinese individuals with BA and 32% of controls (25). It is likely that this risk allele imparts a susceptibility to BA in combination with another insult, such as an infection or toxin. There may in fact be several possible causes of BA that manifest in different patients, with different triggers and risk factors resulting in a similar phenotype. Although BA is not strictly a genetic disease, there has been prior evidence suggesting genetic involvement. The incidence is higher in the Asian population compared to Caucasians with incidence of 1 in 12,000 to 18,000 in Western Europe versus 1.04 to 3.7 per 10,000 in Japan and Taiwan (1,37,38). We have previously demonstrated a functional role for GPC1 as a susceptibility gene for BA, and in that report we summarized previous studies linking genes such as JAG1, CFC1, ZEB2, and others (15). Continuing broad-based genetic studies attempt to understand the contribution of these and other similar genes. Results from these studies may allow us to identify patients at risk for BA.

Perhaps more important than the individual genes uncovered in these studies are the pathways and cellular processes affected by the genes. Abnormally activated Hh signaling appears to be important in BA and in animal models, and thus continued examination of mechanisms that lead to activation of Hh may lead to insights regarding pathogenesis. The accumulated genetic studies also suggest an importance of cilia and polarity pathways, which are connected to Hh activity as well. Supporting this importance of polarity pathways, mice haploinsufficient in Sox17 demonstrate abnormally polarized cholangiocytes, leading to shedding of the cholangiocytes into the bile duct lumen and resulting in obstruction (39). Interestingly, a recent study has identified a novel plant isoflavonoid toxin that has been implicated in outbreaks of BA in Australian livestock (40). Treatment with this toxin results in biliary defects in zebrafish larvae, and in a neonatal cholangiocyte spheroid model the toxin causes loss of cell polarity and obstruction of the lumen. Taken together, these findings suggest a common pathway for genetic and toxin-mediated etiologies of BA, in which intrinsic defects in cholangiocyte polarity lead to a more distal duct obstruction, which then would lead to BA.

Our results demonstrate that inhibition of add3a, a zebrafish ortholog of human ADD3, first identified by GWAS as a candidate BA susceptibility gene, causes abnormalities in biliary structure and function in zebrafish. Furthermore, blockade of the Hh pathway rescues the phenotype, indicating that ADD3 may be acting as part of the Hh pathway. The known functions of ADD3 in cell adhesion and polarity could explain the mechanism of its involvement in BA pathogenesis. Thus, the genetic studies on BA appear to be advancing us toward uncovering pathogenic mechanisms leading to disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Ellen Tsai and Nancy Spinner for advice and helpful discussion. The authors also thank Fred and Suzanne Biesecker Pediatric Liver Center for institutional support.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a fellowship grant awarded to Dr V.T. from the Childhood Liver Disease Research Network (ChiLDReN) (NIH U01 DK062453). The study was also supported by a grant from the American Liver Foundation to Dr Z.C.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen SM, Chang MH, Du JC, et al. Screening for biliary atresia by infant stool color card in Taiwan. Pediatrics 2006; 117:1147–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balistreri WF, Grand R, Hoofnagle JH, et al. Biliary atresia: current concepts and research directions. Summary of a symposium. Hepatology 1996; 23:1682–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischler B, Haglund B, Hjern A. A population-based study on the incidence and possible pre- and perinatal etiologic risk factors of biliary atresia. J Pediatr 2002; 141:217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mezina A, Karpen SJ. Genetic contributors and modifiers of biliary atresia. Dig Dis 2015; 33:408–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Barcelo MM, Yeung MY, Miao XP, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a susceptibility locus for biliary atresia on 10q24.2. Hum Mol Genet 2010; 19:2917–2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaewkiattiyot S, Honsawek S, Vejchapipat P, et al. Association of X-prolyl aminopeptidase 1 rs17095355 polymorphism with biliary atresia in Thai children. Hepatol Res 2011; 41:1249–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai EA, Grochowski CM, Loomes KM, et al. Replication of a GWAS signal in a Caucasian population implicates ADD3 in susceptibility to biliary atresia. Hum Genet 2014; 133:235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Barcelo MM, Yeung MY, Miao XP, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a susceptibility locus for biliary atresia on 10q24.2. Hum Mol Genet 2010; 19:2917–2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molinaro G, Carmona AK, Juliano MA, et al. Human recombinant membrane-bound aminopeptidase P: production of a soluble form and characterization using novel, internally quenched fluorescent substrates. Biochem J 2005; 385:389–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Figini M, Emanueli C, Grady EF, et al. Substance P and bradykinin stimulate plasma extravasation in the mouse gastrointestinal tract and pancreas. Am J Physiol 1997; 272:G785–G793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magnusson I. Anticholeretic effects of substance P and somatostatin. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 1984; 521:1–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trivedi M, Bergasa NV. Serum concentrations of substance P in cholestasis. Ann Hepatol 2010; 9:177–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhlman PA, Hughes CA, Bennett V, et al. A new function for adducin. Calcium/calmodulin-regulated capping of the barbed ends of actin filaments. J Biol Chem 1996; 271:7986–7991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Citterio L, Tizzoni L, Catalano M, et al. Expression analysis of the human adducin gene family and evidence of ADD2 beta4 multiple splicing variants. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003; 309:359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui S, Leyva-Vega M, Tsai EA, et al. Evidence from human and zebrafish that GPC1 is a biliary atresia susceptibility gene. Gastroenterology 2013; 144:1107–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui S, Capecci LM, Matthews RP. Disruption of planar cell polarity activity leads to developmental biliary defects. Dev Biol 2011; 351:229–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farber SA, Pack M, Ho SY, et al. Genetic analysis of digestive physiology using fluorescent phospholipid reporters. Science 2001; 292:1385–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui S, Erlichman J, Russo P, et al. Intrahepatic biliary anomalies in a patient with Mowat-Wilson syndrome uncover a role for the zinc finger homeobox gene zfhx1b in vertebrate biliary development. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011; 52:339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui S, Capecci LM, Matthews RP. Disruption of planar cell polarity activity leads to developmental biliary defects. Dev Biol 2011; 351:229–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews RP, Lorent K, Russo P, et al. The zebrafish onecut gene hnf-6 functions in an evolutionarily conserved genetic pathway that regulates vertebrate biliary development. Dev Biol 2004; 274:245–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang JJ, Tao H, Li J. Hedgehog signaling pathway as key player in liver fibrosis: new insights and perspectives. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2014; 18:1011–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Omenetti A, Bass LM, Anders RA, et al. Hedgehog activity, epithelial-mesenchymal transitions, and biliary dysmorphogenesis in biliary atresia. Hepatology 2011; 53:1246–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.EauClaire SF, Cui S, Ma L, et al. Mutations in vacuolar H+ -ATPase subunits lead to biliary developmental defects in zebrafish. Dev Biol 2012; 365:434–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leyva-Vega M, Gerfen J, Thiel BD, et al. Genomic alterations in biliary atresia suggest region of potential disease susceptibility in 2q37.3. Am J Med Genet A 2010; 152A:886–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng G, Tang CS, Wong EH, et al. Common genetic variants regulating ADD3 gene expression alter biliary atresia risk. J Hepatol 2013; 59:1285–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuoka Y, Li X, Bennett V. Adducin: structure, function and regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci 2000; 57:884–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amano M, Nakayama M, Kaibuchi K. Rho-kinase/ROCK: a key regulator of the cytoskeleton and cell polarity. Cytoskeleton 2010; 67:545–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura K, Fukata Y, Matsuoka Y, et al. Regulation of the association of adducin with actin filaments by Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) and myosin phosphatase. J Biol Chem 1998; 273:5542–5548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Boyer JL. The maintenance and generation of membrane polarity in hepatocytes. Hepatology 2004; 39:892–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feracci H, Connolly TP, Margolis RN, et al. The establishment of hepatocyte cell surface polarity during fetal liver development. Dev Biol 1987; 123:73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stieger B, Landmann L. Effects of cholestasis on membrane flow and surface polarity in hepatocytes. J Hepatol 1996; 24 (suppl 1):128–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rost D, Kartenbeck J, Keppler D. Changes in the localization of the rat canalicular conjugate export pump Mrp2 in phalloidin-induced cholestasis. Hepatology 1999; 29:814–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dumont M, D’Hont C, Lamri Y, et al. Effects of phalloidin and colchicine on diethylmaleate-induced choleresis and ultrastructural appearance of rat hepatocytes. Liver 1994; 14:308–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bischoff M, Gradilla AC, Seijo I, et al. Cytonemes are required for the establishment of a normal Hedgehog morphogen gradient in Drosophila epithelia. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15:1269–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao C, Ogle SA, Schumacher MA, et al. Hedgehog signaling regulates E-cadherin expression for the maintenance of the actin cytoskeleton and tight junctions. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2010; 299:G1252–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shneider BL, Brown MB, Haber B, et al. A multicenter study of the outcome of biliary atresia in the United States, 1997 to 2000. J Pediatr 2006; 148:467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nio M, Ohi R, Miyano T, et al. Five- and 10-year survival rates after surgery for biliary atresia: a report from the Japanese Biliary Atresia Registry. J Pediatr Surg 2003; 38:997–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKiernan PJ, Baker AJ, Kelly DA. The frequency and outcome of biliary atresia in the UK and Ireland. Lancet 2000; 355:25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uemura M, Ozawa A, Nagata T, et al. Sox17 haploinsufficiency results in perinatal biliary atresia and hepatitis in C57BL/6 background mice. Development 2013; 140:639–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorent K, Gong W, Koo KA, et al. Identification of a plant isoflavonoid that causes biliary atresia. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:286ra267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.