Abstract

Bone quantity, or density, has insufficient power to discriminate fracture risk in individuals. Additional measures of bone quality, such as microarchitectural characteristics and bone tissue properties, including the presence of damage, may improve the diagnosis of fracture risk. Microdamage and microarchitecture are two aspects of trabecular bone quality that are interdependent, with several microarchitectural changes strongly correlated to damage risk after compensating for bone density. This study aimed to delineate the effects of microarchitecture and estrogen depletion on microdamage susceptibility in trabecular bone using an ovariectomized sheep model to mimic post-menopausal osteoporosis. The propensity for microdamage formation in trabecular bone of the distal femur was studied using a sequence of compressive and torsional overloads. Ovariectomy had only minor effects on the microarchitecture at this anatomic site. Microdamage was correlated to bone volume fraction and structure model index (SMI), and ovariectomy increased the sensitivity to these parameters. The latter may be due to either increased resorption cavities acting as stress concentrations or to altered bone tissue properties. Pre-existing damage was also correlated to new damage formation. However, sequential loading primarily generated new cracks as opposed to propagating existing cracks, suggesting that pre-existing microdamage contributes to further damage of bone by shifting load bearing to previously undamaged trabeculae, which are subsequently damaged. The transition from plate-like to rod-like trabeculae, indicated by SMI, dictates this shift, and may be a hallmark of bone that is already predisposed to accruing greater levels of damage through compromised microarchitecture.

Keywords: Microdamage, Ovariectomy, Trabecular Bone, Animal Model

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is a bone disease characterized by a loss of bone mass or degradation of architecture that predisposes an individual to fracture, even in the absence of a traumatic event (WHO, 1993). Approximately 10 million Americans currently have osteoporosis, with another 34 million at risk (USDHHS, 2004). Bone mineral density (BMD) as measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) or quantitative computed tomography (qCT) is the standard diagnostic measure for osteoporosis. However, it is neither specific nor sensitive enough to be the sole determinant for increased osteoporotic fracture risk (Schuit, 2004; Seeman and Delmas, 2006). For example, older patients can have a 10-fold increase in fracture risk when compared to BMD-matched young patients (Hui et al., 1988). As such, factors other than density must also affect bone strength and play a role in bone’s mechanical integrity.

Bone quality refers to structural features and intrinsic tissue properties that can determine differences in mechanical behavior not explained by quantity as measured by mineral density (Seeman and Delmas, 2006). In trabecular bone, quality includes microarchitectural characteristics such as structural model index (SMI), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th.), and slenderness, that degrade with aging and are associated with increased fracture risk (Liu et al., 2012; Sornay-Rendu, 2006). Microdamage is also a factor in bone quality. Microdamage presents in the form of cracking or diffuse damage (Schaffler et al., 1995), which can affect mechanical properties at both the tissue and apparent level (Lambers et al., 2013; Wu, 2013). The presence of microdamage can compromise the mechanical integrity, and has been correlated to reductions of bone modulus and strength (Garrison et al., 2011; Lambers et al., 2013; Wu, 2013).

Microdamage burden increases with age (Arlot et al., 2008), consistent with ex vivo experiments demonstrating damage formation in response to fatigue loading at physiologic levels (Wenzel et al., 1996). The increase in microdamage with age coincides with microarchitectural degradation (Garrison et al., 2009) and changes in tissue mineralization related to aging and disease (Zioupos et al., 2008), although it is not clear that this correlation is causal. These factors can be difficult to investigate systematically using human cadaver bone, where many variables are outside of experimental control. However, for experimental purposes, similar structures and densities of microdamage can be induced by monotonic overloading (Moore, 2002), and animal models employing ovariectomy can mimic some of the changes that occur in aging bone (Brennan et al., 2011; Holland et al., 2013; Kennedy et al., 2008).

The goal of this study was to define the contributions of trabecular microarchitecture and ovariectomy status in microdamage formation and propagation in trabecular bone. Ovariectomized sheep were used as a model of post-menopausal osteoporosis (Turner, 2001). This model results in significant degradation of BMD and trabecular microarchitecture in the vertebral body (Giavaresi et al., 2001), iliac crest (Newton, 2004), and femoral neck (Wu et al., 2008) within one year of ovariectomy (Sigrist et al., 2007). In addition, ovine bones are large enough to provide samples that are suitable for mechanical testing (Lill et al., 2002). In this study, 1) microdamage was mechanically induced in trabecular bone from the distal femur through sequential compressive and torsional overloads; 2) relationships between damage, ovariectomy status, and microarchitectural parameters were quantified; and 3) the effects of existing damage on the risk of further damage were quantified.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Sample preparation

Twelve female sheep underwent ovariectomy (OVX) under general anesthesia. The sheep were then returned to pasture until they were sacrificed two years following the OVX. Seven sheep of similar age sacrificed for other studies or due to age were used as controls. Bones were harvested immediately, stripped of soft tissue, and stored at −20° C until they were prepared for testing. The animal care was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Colorado State University and the University of Notre Dame.

Thirty-seven cylindrical cores were prepared from the medial and lateral femoral condyles of the control sheep, and thirty-nine cores were prepared from the femoral condyles of the ovariectomized sheep. The cores were aligned with the principal axes of the trabecular bone using a previously reported protocol (Wang et al., 2004). Briefly, parallelepipeds were cut from the samples and scanned using micro-computed tomography (μ-CT80, Scanco, Brattiselen, Switzerland) at 30 μm resolution while submerged in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The images were converted into micro-finite element models, which were solved to determine the principal mechanical axis. A custom jig was used to align the sample to the calculated axes, and a diamond coring drill (Starlite Industries, Bryn Mawr, PA) was used to prepare a cylindrical sample with a nominal diameter of 8 mm and length of 30 mm.

The prepared specimens were scanned prior to mechanical testing using μ-CT to determine trabecular microarchitecture. A 7.4 mm long region at the center of each sample was scanned at 20 μm isotropic resolution while submerged in PBS. Architecture was quantified using a model free method (Scanco Image Processing Language, Version 4.3) (Table 1). Mineral density levels were quantified using the scanner’s calibration (Kazakia et al., 2008).

Table 1.

Microarchitectural parameters of ovine femoral trabecular bone (Mean ± SD). Values in a row with the same superscript letter are not statistically different.

| Medial Condyle | Lateral Condyle | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| CTL | OVX | CTL | OVX | |

| BV/TV | 0.306 ± 0.046a,b | 0.306 ± 0.042a | 0.281 ± 0.036b,c | 0.260 ± 0.033c |

| SMI | -0.2023 ± 0.352a | -0.116 ± 0.352a,b | 0.0613 ± 0.324b | 0.292 ± 0.260c |

| Slenderness | 3.13 ± 0.45a,b | 3.03 ± 0.47b | 3.29 ± 0.40b,c | 3.53 ± 0.38c |

| BMD (mg-HA/cc) | 265 ± 62a | 267 ± 51a | 243 ± 45a,b | 221 ± 44b |

| TMD (mg-HA/cc) | 909 ± 44 | 922 ± 45 | 908 ± 41 | 925 ± 38 |

BV/TV=volume fraction, SMI=structural model index, Slenderness=Tb.Sp./Tb.Th., BMD=bone mineral density, TMD=tissue mineral density.

2.2 Mechanical testing

Specimens were embedded in brass endcaps to facilitate gripping during microdamage induction (Keaveny et al., 1994). The marrow was removed from the pore space using a water jet while the sample was submerged in water. The ends of the specimens were briefly soaked in ethanol to dry the surface prior to fixing in the endcaps using cyanoacrylate glue (Prism 401, Loctite, Newington, CT).

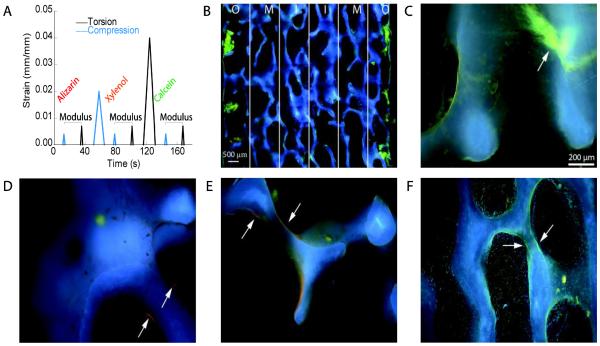

Specimens were subjected to sequential compressive and torsional overloads to induce microdamage (Fig. 1). The elastic and shear modulus were first measured in uniaxial compression to 0.4% strain and torsion to 0.7% shear strain, respectively. Microdamage was then induced by a compressive overload to 2% strain followed by a torsional overload to 4% shear strain at the cylinder surface. Hence, the principal compressive strain for both load cases was the same. Microdamage was labeled before and after each overload as described below. Mechanical tests were performed at room temperature at a strain rate of 0.5% s−1. Compressive strains to 2% and shear strains below 0.7% were measured using a biaxial extensometer (Epsilon, Jackson, WY). The shear overloading exceeded the shear strain limits on the extensometer, and, as such, angular rotation data were acquired from the RVDT during this phase of the tests. Specimens were kept hydrated using saline-saturated gauze wrapped around the exposed length of the specimen. Data were collected at 200 Hz and were filtered using a low pass filter (GCVSPL) to remove high frequency noise. The elastic and shear moduli were measured prior to and following each overload. However, due to drift in the load cell, we were unable to obtain accurate post-damage mechanical properties, or to calculate the modulus loss to compare to the original properties as is normally done (Lambers et al., 2013; Wu, 2013).

Figure 1.

(a) The specimens were subjected to a 0.4% compressive and 0.7% torsional strain to measure modulus, and a 2% compressive and 4% torsional strain to introduce microdamage into the specimens. Different staining agents were introduced after each overload to label microdamage that formed during each loading step. (b) To compensate for the radial variation of strain during torsion, microdamage was quantified based on the radial region in which it was located. (c) Diffuse damage presented in a non-linear morphology. (d) Microcracks that occurred in vivo had a linear morphology that was red in color. (e) Compressive overload microcracking were labeled with xylenol orange and fluoresced a pale orange. (f) Cracks that resulted from the torsional overload were labeled by calcein and had a bright green color.

2.3 Damage quantification

Damage was labeled by a sequence of calcium chelating fluorophores (O'Brien et al., 2003). Specimens were soaked in 0.5 mM alizarin complexone (ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, OH) prior to mechanical testing to label microdamage that was present in vivo or during specimen preparation. After the compressive overload, specimens were stained with 0.5 mM xylenol orange (ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, OH). Finally, after torsional overloading, specimens were stained with 0.5 mM calcein (ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, OH). In each case, specimens were stained for 2 hours under vacuum, and rinsed with deionized water after staining.

Following testing, specimens were dehydrated in a series of ethanol solutions ending with a 100% ethanol solution for 12 hours. They were then embedded in transparent methyl methacrylate (MMA, Aldrich Chemical Company Inc., Milwaukee, WI) under vacuum. Two 200 μm thick sections of each core were cut along the long axis of the specimen using a diamond wire saw (DDK Inc., Wilmington, DE). The sections were mounted on glass slides using Eukitt mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), and polished to a final thickness of approximately 150 μm starting with 600 grit paper and ending with 1/4 μm diamond paste (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL).

Microdamage was quantified using epifluorescent microscopy. The sections were imaged at 100x magnification using UV excitation at an excitation wavelength of 365 nm (UV1A filter, Nikon Inc., Melville, NY). Images were captured over an 8x8 mm region in the center of the specimen using a CCD camera (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada), and composited into a single image (Photoshop, Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). The outer 0.4 mm of the samples were excluded from the microdamage quantification to eliminate labeling of the surfaces cut during specimen preparation. The composite image was divided into three longitudinal regions of equal radius about the central axis of the specimen to identify regions of differing shear strain during torsion (Fig. 1) (Wang, 2005; Wang and Niebur, 2006; Wu, 2013).

The length of microcracks and area of diffuse damage regions were measured using ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD) as described previously (Wu, 2013). Briefly, bone area (B.Ar.) was found by thresholding the images. Diffuse damage area (Dx.Ar.) was identified as stained regions on the bone that did not present in a linear morphology, and was normalized by B.Ar. Linear microcracks were identified as stain that showed permeation into the bone and distinct edges that presented in a linear morphology (Fig. 1). Cracks in cross-hatched patterns were each counted as separate linear microcracks. The crack density (Cr.Dn.) was defined as the number of cracks normalized by bone area. The mean crack length (Cr.Ln.) for each sample was found by dividing the sum of the lengths of the cracks by the number of cracks. Crack surface density (Cr.S.Dn.), was found by multiplying the Cr.Ln. by the Cr.Dn.

Crack propagation was also quantified. Cracks with only one staining agent were assumed to be newly formed during the preceding load, while cracks showing more than one adjacent staining agent were assumed to have propagated from one loading mode to the next.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed using JMP IN 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Parametric tests were applied to the microarchitecture measures, as all parameters were normally distributed and had a large sample size (n>30). Microdamage was not normally distributed. Therefore, a Wilcoxon/Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine differences between ovariectomy groups and specimen regions. ANCOVA regression was used to assess the effects of microarchitecture and pre-existing damage on quantified damage parameters, with ovariectomy status as a nominal factor. Damage and microarchitecture correlations were calculated for each site and ovariectomy group. A p-value of 0.05 was considered to be significant for all tests.

3. Results

Trabecular bone in the medial condyle was denser and more plate-like than the lateral condyle. Moreover, the trabecular bone in the medial condyle experienced no significant microarchitectural degradation following OVX. In contrast, BV/TV decreased and SMI increased in the lateral condyle following OVX (Table 1). The dependence of the moduli on BV/TV did not differ between the CTL and OVX groups. Young’s modulus was lower in the OVX samples when BV/TV was included as a covariate in the model (p<0.03, ANCOVA, Fig. 2), but the shear moduli did not differ between groups (p = 0.13).

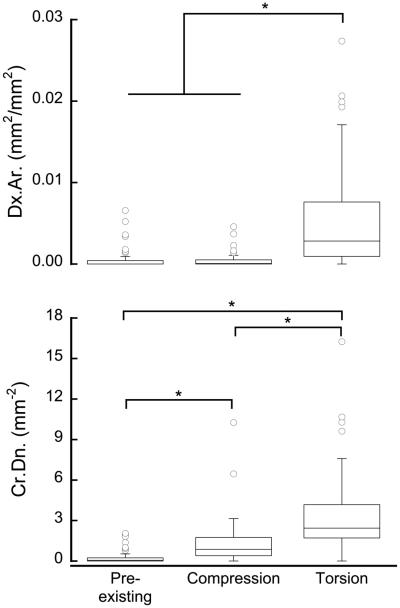

Figure 2.

The modulus of the samples increased with volume fraction. The OVX samples had a mean modulus of 1217 MPa vs 1360 MPa in the control samples when BV/TV was included as a covariate (p<0.03, ANCOVA).

Both Dx.Ar. and Cr.Dn. generated by torsional loading were higher than that generated by compressive loading (p<0.0001, Kruskal-Wallis, Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Both Dx.Ar. (a) and Cr.Dn. (b) caused by torsion were greater than pre-existing damage or that caused by compression. Boxes show the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile (n=76). The error bars span the range with outliers marked by circles. (p<0.05, Kruskal-Wallis).

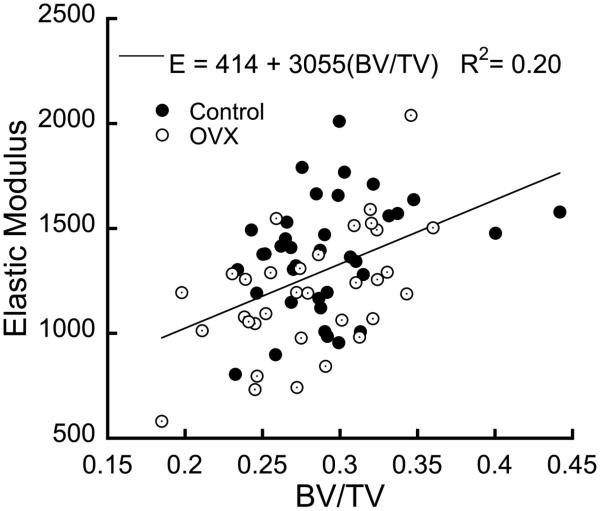

Microdamage was associated with decreased bone volume fraction (Fig. 4). Pre-existing Cr.Dn. decreased with increasing BV/TV in both the CTL (p<0.02, R2=0.15) and OVX groups (p=0.001, R2=0.31), with a more negative slope in the OVX group (p<0.01, Fig. 4a). Pre-existing Cr.Dn. also increased with increasing SMI in the OVX group (p=0.001, R2=0.31), but was not significantly correlated to SMI in the CTL group (data not shown). Similarly, pre-existing Dx.Ar. correlated negatively with BV/TV (p<0.0001, R2=0.36) and positively with SMI (p<0.0001, R2=0.37) in the OVX group, but not in the CTL group.

Figure 4.

(a) Pre-existing damage and (b) compressive load damage were negatively correlated to BV/TV for both OVX and CTL groups (p < 0.02, ANCOVA) with a more negative slope in the OVX group (p < 0.01). (c) Torsional load damage was not correlated to BV/TV or SMI for either group.

Lower volume fraction also increased the susceptibility to damage during overloads (Fig. 4b). The Cr.Dn. attributed to the compressive overload decreased with BV/TV and increased with SMI for both the CTL (p<0.005, R2=0.24, p<0.05, R2=0.11) and OVX groups (p<0.0001, R2=0.36, p<0.002, R2=0.25). The OVX group had a more negative slope with respect to BV/TV (p<0.03) and a more positive slope with respect to SMI than the CTL group (p<0.05), in agreement with the pre-existing damage. Dx.Ar. resulting from the compressive overload also correlated negatively with BV/TV in both the CTL (p<0.03, R2=0.14) and OVX groups (p<0.002, R2=0.24). However, the Dx.Ar. due to compressive loading only correlated with increasing SMI for the OVX group (p<0.002, R2=0.24), not the CTL group.

In contrast to the pre-existing and compressive overload, no correlations to microarchitecture were found for microdamage induced from the torsional overload (Fig. 4c).

Linear crack density was correlated to diffuse damage area for all three loading modes in both CTL and OVX groups. Pre-existing Cr.Dn. and Dx.Ar. were weakly correlated in the CTL (p<0.01, R2=0.19) and OVX groups (p<0.001, R2=0.62). Considering the damage resulting from the compressive overload, Cr.Dn. correlated with Dx.Ar. for the CTL (p<0.001, R2=0.28) and OVX groups (p<0.001, R2=0.44), with the correlation in the OVX group being significantly more positive (p<0.05). Considering only the torsional load, Cr.Dn. and Dx.Ar. were also positively correlated in the CTL (p<0.001, R2=0.32) and OVX groups (p<0.02, R2=0.16), but with no difference in slope.

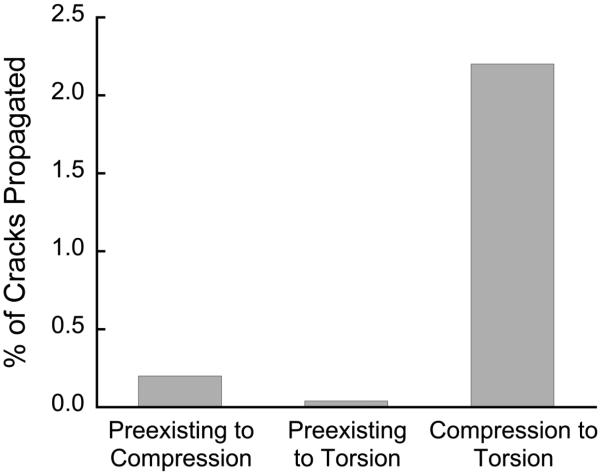

Only 1.5% of cracks propagated, indicated by two adjacent staining agents (Fig. 5). Approximately 0.2% of the cracks induced by the compressive overload propagated from in vivo cracks, and only 0.04% of cracks from the torsional overload propagated from in vivo cracks. Of all the cracks resulting from torsion, 2.2% propagated from cracks initiated during the compressive overload. Crack propagation was no more likely in OVX compared to CTL groups, or in the lateral vs. medial condyle (p>0.05).

Figure 5.

Cracks rarely propagated from one loading mode to another. The greatest number of cracks propagated from compressive loading to torsional loading (data is pooled across 76 samples).

The presence of microdamage increased the propensity for subsequent microdamage. In the CTL group, the density of cracks due to the compressive load was positively correlated with the pre-existing Cr.Dn. (p<0.05, R2=0.12), and both Dx.Ar. and Cr.Dn. due to the torsional load were positively correlated with microdamage from compression (p<0.02, R2=0.15, p=0.0002, R2=0.32). Both of these correlations were independent of SMI and BV/TV. In the OVX group, the Cr.Dn. from the compressive load was similarly positively correlated with pre-existing Cr.Dn. (p<0.0001, R2=0.37) as was Dx.Ar. (p<0.0001, R2=0.36), and both increased with decreasing BV/TV.

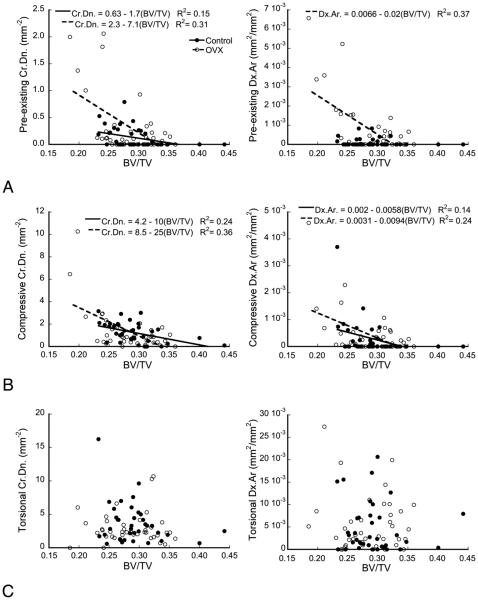

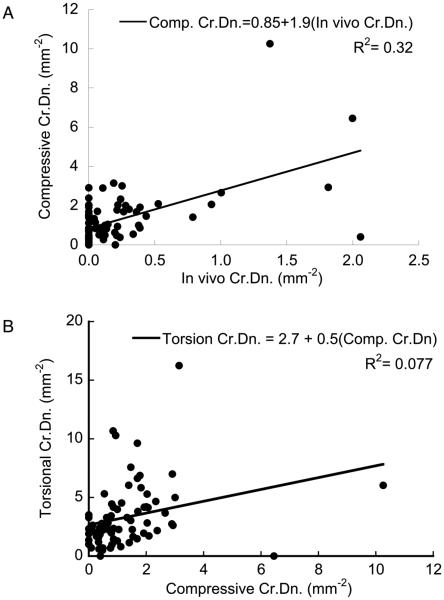

Finally, we pooled the CTL and OVX groups, because ANCOVA indicated that the ovariectomy status was not a significant factor in the correlations between existing and induced damage (Fig. 6). Compressive Cr.Dn was correlated to the pre-existing crack density (p<0.001, R2=0.32), and torsional Cr.Dn. was correlated to the compressive crack density, but much more weakly (p<0.02, R2=0.077). However, the coefficient of determination between the compressive and torsional microdamage increased to 0.20 and remained significant with the removal of the two outlier points with the highest compressive Cr.Dn.

Figure 6.

(a) Damage resulting from the compressive overload was positively correlated to the pre-existing Cr.Dn (p < 0.01). (b) The density of cracks caused by torsional overloading was weakly correlated to that induced by the compressive overload (p < 0.02). When the two points with the highest compressive Cr.Dn. values were excluded, the regression between torsional and compressive Cr.Dn. remained significant, while the coefficient of determination increased to 0.20. These correlations were independent of OVX status (ANCOVA).

4. Discussion

Damage in porous materials can depend on the solid volume fraction, pore size, architecture, and the material properties of the underlying tissue. The results of this study indicate that microdamage formation in trabecular bone is primarily driven by alterations in volume fraction and microarchitecture. However, we also found that damage formation in bone from ovariectomized animals was more sensitive to decreases in volume fraction, suggesting that alterations in tissue properties (Brennan et al., 2009; Brennan et al., 2011) or increased remodeling sites may play a role (Slyfield et al., 2012). Moreover, bone with pre-existing microdamage, whether diffuse or linear, is more likely to develop further microdamage, primarily through the formation of new cracks rather than propagation of existing cracks. As cracks form, the effective modulus of the tissue is reduced (Burr, 2003; Keaveny et al., 1994; Moore, 2002; Wu, 2013), which in turn alters the loading paths through the porous architecture by stress redistribution (Liu et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2010a, b; Wang and Niebur, 2006). As the stress is redistributed to new regions, new cracks form in the newly loaded regions, further decreasing both modulus and yield strength (Hernandez et al., 2014; Moore and Gibson, 2001). This process can continue until the bone is degraded to the point of overt fracture. As such, microarchitecture plays a key role in determining locations of new microdamage formation, and the ultimate cascade to failure (Moore, 2002). This is also consistent with the higher levels of damage resulting from torsional loading. Bending of trabecular rods and shearing or bending of trabecular plates is induced when the stress is misaligned from the principal trabecular orientations, resulting in tensile strains in the tissue (Niebur et al., 2002; Niebur et al., 2001; Shi et al., 2009) – which is associated with a lower damage threshold – and deformation of transverse or oblique trabeculae that may otherwise experience minimal loads (Sanyal et al., 2012). As such, bone with compromised architecture is more likely to incur damage during excessive loading, and the degradation of the bone will advance as the presence of damage decreases possible new paths for stress redistribution. This process is further affected by ovariectomy, which may cause changes in tissue composition and modulus (Brennan et al., 2009; Brennan et al., 2011) or increase the presence of remodeling sites in this large animal model.

The primary strengths of this study included employing sequential loading in two modes, and sequential labeling with fluorochromes allowed damage incurred during each loading mode to be differentiated. The ability to differentiate between damage caused from each load allowed for the ability to characterize not only the relative levels of damage from each loading mode, but also the propagation characteristics of damage through bone.

This study also has important limitations. Minimal differences in architecture were seen in the femoral condyles in the ovariectomized sheep model (Kreipke et al., 2014). Because of this, the samples were not representative of osteoporotic human bone (Krug et al., 2005). However, the samples in this study provided a wide range of architecture (Table 1), allowing improved understanding of architectural effects on damage formation and propagation. The effect of ovariectomy on circulating hormone levels was not quantified, but is assumed to be similar to previous studies of ovariectomized sheep. Finally, we did not correlate damage to degradation in mechanical properties, due to errors in the data collection. Ultimately, it is the effect of microcracks and diffuse damage on mechanical properties that defines the degree to which the bone is functionally damaged (Hernandez et al., 2014).

The analysis focused on BV/TV and SMI as architectural measures. Trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp.) or trabecular thickness (Tb.Th.) were also correlated with the induced damage, as they were highly correlated to BV/TV, SMI, or both (see supplemental data).

New crack formation was more common than propagation of existing cracks. While pre-existing microdamage was an indicator of damage risk, consistent with findings in earlier studies (Hernandez et al., 2014), crack propagation was not a common mode of new damage. This tendency of bone to form new cracks rather than propagate existing cracks has been observed in both cortical (O'Brien et al., 2003) and trabecular bone (Goff et al., 2015; Wang, 2005; Wang and Niebur, 2006; Wu, 2013). Taken together, the evidence suggests that damage is more dependent on alterations in the stress field through the trabecular network than stress concentrations at existing damage, and that similar crack arrest mechanisms are active in both cortical and trabecular bone tissue.

Correlations of damage to microarchitecture and pre-existing damage agree well with previous studies that examined the propagation characteristics of microdamage in human femoral trabecular bone subjected to sequential loading in multiple modes (Wu, 2013) and human vertebral trabecular bone subjected to axial loading (Lambers et al., 2013). Interestingly, different microarchitectural parameters can be associated with increased numbers of damage sites and increased size of damage sites when 3-dimensional methods are used to quantify damage (Lambers et al., 2014). Extending these results, this study also found significant interactions between BV/TV and pre-existing damage, showing that impaired microarchitecture in addition to pre-existing high levels of damage lead to even greater risk of microdamage.

Cr.Dn. showed strong correlations with Dx.Ar. for each respective loading mode. This indicates that bone that is pre-disposed to damage is more susceptible to forming both morphologies of damage. However, few microcracks propagated from regions of diffuse damage. The lack of microcracks propagating from regions of diffuse damage suggests that diffuse damage does not directly lead to the formation of microcracks through the coalescence of the many nanoscale cracks that comprise diffuse damage. Therefore, the introduction of each damage morphology into the tissue is an independent process. The correlations of Cr.Dn. to Dx.Ar. are contrary to results found in a previous study (Vashishth et al., 2000), which found no correlations between diffuse and linear microdamage. In that study, Dx.Ar. in human vertebral trabecular bone was correlated to Cr.Dn. from a previous study on the same specimens. The differences in correlation results may be attributable to differences in loading mode or trabecular architecture between the vertebral body and the distal femur, the age of the individuals, or the use of different damage labeling methodologies.

This study supports the concept that bone microdamage is dependent on trabecular microarchitecture and pre-existing microdamage. The correlations found in this study between damage and microarchitecture, as well as new crack formation behavior agree with other studies (O'Brien et al., 2003; Wu, 2013). Taken together, these trends support the proposed mechanism of the mechanical failure of bone through altered stress distributions in the trabecular compartment (Moore, 2002). As the pathogenesis of osteoporosis progresses, the trabecular architecture degrades. This renders the individual trabeculae more susceptible to damage (Liu et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2010a), which in turn reduces the stiffness of the damaged trabeculae (Keaveny et al., 1994) and displaces loads to the initially weaker, less stiff trabeculae (Moore and Gibson, 2001). If left unchecked, this process may repeat until overt fracture occurs. Therefore, diagnostic imaging methods that allow trabecular microarchitecture to be measured in vivo, such as high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (Liu et al., 2012), may offer improved sensitivity for predicting risk of osteoporotic fracture.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, NIAMS Grant AR052008. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIAMS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors certify that they have no conflict of interest with regard to this manuscript.

References Cited

- Arlot ME, Burt-Pichat B, Roux JP, Vashishth D, Bouxsein ML, Delmas PD. Microarchitecture influences microdamage accumulation in human vertebral trabecular bone. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2008;23:1613–1618. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, Kennedy, Lee, Rackard, O'Brien Biomechanical properties across trabeculae from the proximal femur of normal and ovariectomised sheep. Journal of Biomechanics. 2009;42:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan O, Kennedy OD, Lee TC, Rackard SM, O'Brien FJ, McNamara LM. The effects of estrogen deficiency and bisphosphonate treatment on tissue mineralisation and stiffness in an ovine model of osteoporosis. J Biomech. 2011;44:386–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr D. Microdamage and bone strength. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(Suppl 5):S67–72. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison JG, Gargac JA, Niebur GL. Shear strength and toughness of trabecular bone are more sensitive to density than damage. Journal of biomechanics. 2011;44:2747–2754. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison JG, Slaboch CL, Niebur GL. Density and architecture have greater effects on the toughness of trabecular bone than damage. Bone. 2009;44:924–929. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giavaresi G, Fini M, Torricelli P, Martini L, Giardino R. The ovariectomized ewe model in the evaluation of biomaterials for prosthetic devices in spinal fixation. The International journal of artificial organs. 2001;24:814–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff MG, Lambers FM, Nguyen TM, Sung J, Rimnac CM, Hernandez CJ. Fatigue-induced microdamage in cancellous bone occurs distant from resorption cavities and trabecular surfaces. Bone. 2015;79:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez CJ, Lambers FM, Widjaja J, Chapa C, Rimnac CM. Quantitative relationships between microdamage and cancellous bone strength and stiffness. Bone. 2014;66:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JC, Brennan O, Kennedy OD, Rackard S, O'Brien FJ, Lee TC. Subchondral osteopenia and accelerated bone remodelling post-ovariectomy - a possible mechanism for subchondral microfractures in the aetiology of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee? Journal of Anatomy. 2013;222:231–238. doi: 10.1111/joa.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui SL, Slemenda CW, Johnston CC., Jr. Age and bone mass as predictors of fracture in a prospective study. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1988;81:1804–1809. doi: 10.1172/JCI113523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazakia GJ, Burghardt AJ, Cheung S, Majumdar S. Assessment of bone tissue mineralization by conventional x-ray microcomputed tomography: Comparison with synchrotron radiation microcomputed tomography and ash measurements. Medical physics. 2008;35:3170–3179. doi: 10.1118/1.2924210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keaveny TM, Wachtel EF, Guo XE, Hayes WC. Mechanical behavior of damaged trabecular bone. Journal of biomechanics. 1994;27:1309–1318. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy OD, Brennan O, Mauer P, O'Brien FJ, Rackard SM, Taylor D, Lee TC. The behaviour of fatigue-induced microdamage in compact bone samples from control and ovariectomised sheep. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2008;133:148–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreipke TC, Rivera NC, Garrison JG, Easley JT, Turner AS, Niebur GL. Alterations in trabecular bone microarchitecture in the ovine spine and distal femur following ovariectomy. Journal of biomechanics. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug R, Banerjee S, Han ET, Newitt DC, Link TM, Majumdar S. Feasibility of in vivo structural analysis of high-resolution magnetic resonance images of the proximal femur. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2005;16:1307–1314. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1907-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambers FM, Bouman AR, Rimnac CM, Hernandez CJ. Microdamage caused by fatigue loading in human cancellous bone: Relationship to reductions in bone biomechanical performance. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambers FM, Bouman AR, Tkachenko EV, Keaveny TM, Hernandez CJ. The effects of tensile-compressive loading mode and microarchitecture on microdamage in human vertebral cancellous bone. J Biomech. 2014;47:3605–3612. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lill CA, Fluegel AK, Schneider E. Effect of ovariectomy, malnutrition and glucocorticoid application on bone properties in sheep: A pilot study. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2002;13:480–486. doi: 10.1007/s001980200058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XS, Stein EM, Zhou B, Zhang CA, Nickolas TL, Cohen A, Thomas V, McMahon DJ, Cosman F, Nieves J, Shane E, Guo XE. Individual trabecula segmentation (its)-based morphological analyses and microfinite element analysis of hr-pqct images discriminate postmenopausal fragility fractures independent of dxa measurements. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27:263–272. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TL, Gibson LJ. Modeling modulus reduction in bovine trabecular bone damaged in compression. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2001;123:613–622. doi: 10.1115/1.1407828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TLA, Gibson LJ. Microdamage accumulation in bovine trabecular bone in uniaxial compression . Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2002;124:63–71. doi: 10.1115/1.1428745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton BO, Cooper RC, Gilbert JA, Johnson RB, Zardiackas LD. The ovariectomized sheep as a model for human bone loss. Journal of comparative pathology. 2004;130:323–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebur GL, Feldstein MJ, Keaveny TM. Biaxial failure behavior of bovine tibial trabecular bone. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2002;124:699–705. doi: 10.1115/1.1517566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebur GL, Yuen JC, Burghardt AJ, Keaveny TM. Sensitivity of damage predictions to tissue level yield properties and apparent loading conditions. Journal of biomechanics. 2001;34:699–706. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien FJ, Taylor D, Lee TC. Microcrack accumulation at different intervals during fatigue testing of compact bone. Journal of biomechanics. 2003;36:973–980. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal A, Gupta A, Bayraktar HH, Kwon RY, Keaveny TM. Shear strength behavior of human trabecular bone. Journal of biomechanics. 2012;45:2513–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffler MB, Choi K, Milgrom C. Aging and matrix microdamage accumulation in human compact bone. Bone. 1995;17:521–525. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuit S, Van der Klift M, Weel A, De Laet C. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: The rotterdam study. Bone. 2004;34:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman E, Delmas PD. Bone quality--the material and structural basis of bone strength and fragility. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;354:2250–2261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra053077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Wang X, Niebur GL. Effects of loading orientation on the morphology of the predicted yielded regions in trabecular bone. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2009;37:354–362. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9619-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi XT, Liu XS, Wang X, Guo XE, Niebur GL. Effects of trabecular type and orientation on microdamage susceptibility in trabecular bone. Bone. 2010a;46:1260–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi XT, Liu XS, Wang X, Guo XE, Niebur GL. Type and orientation of yielded trabeculae during overloading of trabecular bone along orthogonal directions. Journal of biomechanics. 2010b;43:2460–2466. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist IM, Gerhardt C, Alini M, Schneider E, Egermann M. The long-term effects of ovariectomy on bone metabolism in sheep. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism. 2007;25:28–35. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0724-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slyfield CR, Tkachenko EV, Fischer SE, Ehlert KM, Yi IH, Jekir MG, O'Brien RG, Keaveny TM, Hernandez CJ. Mechanical failure begins preferentially near resorption cavities in human vertebral cancellous bone under compression. Bone. 2012;50:1281–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.02.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sornay-Rendu E, Boutroy S, Munoz F, Delmas PD. Alterations of cortical and trabecular architecture are associated with fractures in postmenopausal women, partially independent of decreased BMD measured by dxa: The ofely study. Journal of bone and mineral research. 2006;22:425–433. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner AS. Animal models of osteoporosis--necessity and limitations. European cells & materials. 2001;1:66–81. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v001a08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS Bone health and osteoporosis: A report of the surgeon general. 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashishth D, Koontz J, Qiu SJ, Lundin-Cannon D, Yeni YN, Schaffler MB, Fyhrie DP. In vivo diffuse damage in human vertebral trabecular bone. Bone. 2000;26:147–152. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Guyette J, Liu X, Roeder R, Niebur G. Axial-shear interaction effects on microdamage in bovine tibial trabecular bone. European journal of morphology. 2005;41:61–70. doi: 10.1080/09243860500095570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Liu X, Niebur GL. Preparation of on-axis cylindrical trabecular bone specimens using micro-ct imaging. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2004;126:122–125. doi: 10.1115/1.1645866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Niebur GL. Microdamage propagation in trabecular bone due to changes in loading mode. Journal of biomechanics. 2006;39:781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel TE, Schaffler MB, Fyhrie DP. In vivo trabecular microcracks in human vertebral bone. Bone. 1996;19:89–95. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(96)88871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Consensus development conference: Diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of osteoporosis. American Journal of Medicine. 1993;941:646–650. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90218-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Laneve AJ, Niebur GL. In vivo microdamage is an indicator of susceptibility to initiation and propagation of microdamage in human femoral trabecular bone. Bone. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZX, Lei W, Hu YY, Wang HQ, Wan SY, Ma ZS, Sang HX, Fu SC, Han YS. Effect of ovariectomy on BMD, micro-architecture and biomechanics of cortical and cancellous bones in a sheep model. Medical engineering & physics. 2008;30:1112–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zioupos P, Gresle M, Winwood K. Fatigue strength of human cortical bone: Age, physical, and material heterogeneity effects. Journal of biomedical materials research Part A. 2008;86:627–636. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.