Abstract

The tuberculosis drug bedaquiline inhibits mycobacterial F-ATP synthase by binding to its c subunit. Using the purified ε subunit of the synthase and spectroscopy, we previously demonstrated that the drug interacts with this protein near its unique tryptophan residue. Here, we show that replacement of ε's tryptophan with alanine resulted in bedaquiline hypersusceptibility of the bacteria. Overexpression of the wild-type ε subunit caused resistance. These results suggest that the drug also targets the ε subunit.

TEXT

The diarylquinoline bedaquiline (trade name Sirturo, code names TMC207 and R207910) is a new tuberculosis drug discovered by Koen Andries and colleagues (1, 2, 16). The drug was shown to inhibit F-ATP synthase of mycobacteria (1). Genetic, biochemical, and modeling studies demonstrated that the c subunit of the F-ATP synthase, forming the membrane-embedded rotary ring of the enzyme, contains the binding site of the drug (1–9). Recent structural studies suggest that bound bedaquiline prevents the rotor ring from acting as an ion shuttle and thus stalls the ATP synthase operation (9).

Using recombinant purified F-ATP synthase ε subunit, which plays a key role in coupling proton translocation across the membrane with the catalytic site events in the cytoplasm, we showed previously via tryptophan fluorescence and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy that the drug interacts with this subunit near its unique and Mycobacterium-specific N-terminal tryptophan residue 16 (10). Based on these in vitro data, we proposed that bedaquiline may target, in addition to the c subunit, the ε subunit of F-ATP synthase (10). Here, we carried out genetic studies to provide in vivo evidence for this second binding site of bedaquiline on the F-ATP synthase.

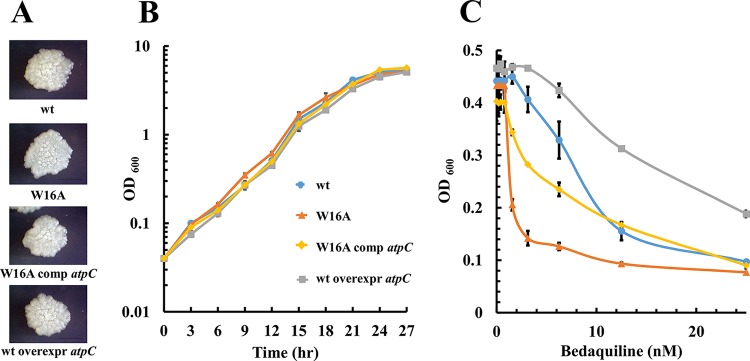

To test our hypothesis that bedaquiline binds to the ε subunit near its tryptophan 16 residue, we replaced this amino acid with alanine by mutating the corresponding codon in the genome of Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 (ATCC 700084). We predicted that this amino acid exchange would change the bedaquiline susceptibility of the bacteria, either to hyposensitivity, if the drug binds more weakly to the mutated form of the ε subunit, or to hypersensitivity, if the mutation allows stronger binding. Site-directed, oligonucleotide-based genome mutagenesis (“recombineering” [11]) was carried out as described previously (12). Briefly, electrocompetent M. smegmatis harboring plasmid pJV53 and thus expressing the mycobacterial phage Che9c recombineering genes gp60 and gp61 was transformed with the double-stranded DNA oligonucleotide GGTGTGGCTGATCTGAACGTCGAGATCGTCGCCGTCGAGCGTGAGCTCGCGTCCGGACCCGCTACGTTCGTGTTCACCCGCACCACCGCCGGTGAGATCG (Integrated DNA Technologies, USA) containing the desired GCG alanine codon (underlined) to replace the genomic TGG tryptophan codon in position 16 of the ε subunit-encoding atpC gene. Colonies were PCR screened with 2 different primer pairs both containing the forward primer GCGCTTCCTGAGCCAGAACATGA. One pair contained the reverse primer CGAACGTAGCGGGTCCGGACCA, matching the wild-type codon for tryptophan, and one pair contained the reverse primer CGAACGTAGCGGGTCCGGACGC, matching the mutated codon for alanine. For colonies that showed positive PCRs with the pair containing the primer matching the mutated version and a negative PCR with the pair containing the wild-type version of the gene, the introduction of the desired mutation was verified by sequencing (AIT Biotech, Singapore). Figure 1A and B show that the resulting strain M. smegmatis atpCW16A displayed a growth behavior on Middlebrook 7H10 agar and in 7H9 broth (Becton Dickinson, USA) that was indistinguishable from that of the parental wild-type strain. This shows that the tryptophan-to-alanine alteration in the ε subunit of the F-ATP synthase did not affect bacterial growth (13). To determine whether the amino acid replacement changed bedaquiline susceptibility of the bacterium, growth inhibition dose-response curves were determined using the broth dilution method as described earlier (14) and bedaquiline purchased from Genegobio (Los Angeles, CA). Figure 1C shows that whereas wild-type M. smegmatis showed a MIC50 of 10 nM, M. smegmatis atpCW16A showed a MIC50 of 2 nM, a 5-fold-increased sensitivity to bedaquiline. The observed hypersusceptibility of the bacterium may suggest that the replacement of the bulky tryptophan with an alanine provides more space for a stronger binding of the drug to the ε subunit. The hypersensitivity phenotype was complemented by the introduction of a wild-type copy of atpC carried by the plasmid pMV262-atpC and expressed by the plasmid's hsp60 promoter (Fig. 1C). Together, these results suggest that bedaquiline interacts with the ε subunit of the F-ATP synthase in intact bacilli. pMV262-atpC was constructed by inserting a PCR-amplified DNA fragment of the coding sequence of the atpC gene into plasmid pMV262 via its BamHI and PstI sites (15). As the atpC coding sequence contained an internal BamHI site, the cloning was carried out in a two-step PCR process to eliminate this restriction site by introduction of a silent mutation. First, two overlapping atpC fragments, lacking the original BamHI site, were amplified using the primer pairs Forward-BamHI (GGTGTGGATCCGCTGATCTGAACG)/Internal-reverse (CTCCACGAGGATTCGGACGGTCTC) and Internal-forward (GAGACCGTCCGAATCCTCGTGGAG)/Reverse-PstI (ATGGACGCTGCAGTCGATGTGACTAG). Then, using these two fragments as the template, the entire (BamHI site-mutated) atpC coding sequence was amplified with primers Forward-BamHI and Reverse-PstI.

FIG 1.

Growth and bedaquiline susceptibility of wild-type M. smegmatis and various genetic derivatives. (A) Growth on solid medium. Colonies are shown after 4 days of incubation. (B) Growth in liquid medium. (C) Bedaquiline growth inhibition dose-response curves. wt, wild-type M. smegmatis; W16A, M. smegmatis atpCW16A; W16A comp atpC, M. smegmatis atpCW16A complemented with a wild-type copy of the gene encoding the ε subunit via the introduction of plasmid pMV262-atpC; wt overexpr atpC, wild-type M. smegmatis overexpressing wild-type ε protein via introduction of pMV262-atpC; OD600, optical density at 600 nm. The experiments were carried out three times independently. Mean values with standard deviations are shown.

To further confirm the binding of bedaquiline to the ε subunit in vivo, we carried out an overexpression experiment. If the drug indeed inhibits F-ATP synthase in intact bacteria by binding to the ε subunit of the enzyme, increasing the intracellular target concentration, i.e., overexpression of the wild-type ε subunit in wild-type bacteria, is expected to result in reduced sensitivity, i.e., increased resistance to bedaquiline. Figure 1C shows that this is the case. Wild-type M. smegmatis carrying wild-type ε subunit-overexpressing plasmid pMV262-atpC showed a 2.5-fold increase in MIC50, from 10 nM to 25 nM, compared to wild-type bacteria.

Taken together, these genetic results support a model in which bedaquiline inhibits mycobacterial F-ATP synthase via a novel second mechanism involving the enzyme's ε subunit in addition to binding to its c subunit. Our data suggest that the drug interacts with the ε subunit and that this binding occurs close to tryptophan 16 of the protein. The results further suggest that the replacement of the bulky side chain of tryptophan 16 with the smaller side chain of alanine allows for a tighter binding of the drug. In conclusion, we provide in vivo evidence for a second binding site of the new tuberculosis drug bedaquiline involving subunit ε of the mycobacterial F-ATP synthase. This information may be useful for the discovery of the next generation of diarylquinolines. In this context, it is important to note that in our previous biophysical in vitro and modeling studies (10), we proposed a detailed binding epitope involving in addition to tryptophan 16, characterized here genetically, arginine 37 and threonine 19 in the ε subunit and phenylalanine 50 in the c subunit. To begin to dissect the details of the second binding epitope of bedaquiline on the F-ATP synthase genetically, we replaced arginine 37 (CGG) in the ε subunit with glycine (GGG) by recombineering. We were able to generate viable bacteria carrying the desired mutation, and the mutated strain had the same generation time as that of wild-type bacteria, i.e., it showed wild-type-like growth behavior. Interestingly, bedaquiline MIC determinations showed no shift in drug susceptibility in the mutant M. smegmatis strain in which arginine 37 was replaced by glycine (data not shown). There are several possible explanations why changing arginine 37 in the ε subunit had no effect on bedaquiline MIC. First, the proposed binding model suggesting an interaction with arginine 37 is not correct and may require modification. Alternatively, the proposed binding model may be correct; however, the contribution of arginine 37 to bedaquiline binding may not be detectable by genetic means, i.e., the interaction might be too weak to cause phenotypic consequences when interrupted. In general terms, genetic confirmation of a biochemically determined binding epitope may have limitations. A comprehensive mutational analysis in which all proposed interacting amino acid residues are exchanged for multiple different amino acids is in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health's National Medical Research Council under its grant NMRC CBRG12nov049 to T.D. and G.G. S.K. receives a Research Scholarship from Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine.

We thank Graham Hatfull, University of Pittsburgh, for sharing his recombineering tools. We are grateful to Bill Jacobs, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, for sharing plasmid pMV262.

S.K. and G.B. carried out the experiments. G.G. and T.D. wrote the manuscript.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andries K, Verhasselt P, Guillemont J, Göhlmann HW, Neefs JM, Winkler H, Van Gestel J, Timmerman P, Zhu M, Lee E, Williams P, de Chaffoy D, Huitric E, Hoffner S, Cambau E, Truffot-Pernot C, Lounis N, Jarlier V. 2005. A diarylquinoline drug active on the ATP synthase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 307:223–227. doi: 10.1126/science.1106753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koul A, Dendouga N, Vergauwen K, Molenberghs B, Vranckx L, Willebrords R, Ristic Z, Lill H, Dorange I, Guillemont J, Bald D, Andries K. 2007. Diarylquinolines target subunit c of mycobacterial ATP synthase. Nat Chem Biol 3:323–324. doi: 10.1038/nchembio884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jonge MR, Koymans LH, Guillemont JE, Koul A, Andries K. 2007. A computational model of the inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis ATPase by a new drug candidate R207910. Proteins 67:971–980. doi: 10.1002/prot.21376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huitric E, Verhasselt P, Koul A, Andries K, Hoffner S, Andersson DI. 2010. Rates and mechanisms of resistance development in Mycobacterium tuberculosis to a novel diarylquinoline ATP synthase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:1022–1028. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01611-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haagsma AC, Podasca I, Koul A, Andries K, Guillemont J, Lill H, Bald D. 2011. Probing the interaction of the diarylquinoline TMC207 with its target mycobacterial ATP synthase. PLoS One 6:e23575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segala E, Sougakoff W, Nevejans-Chauffour A, Jarlier V, Petrella S. 2012. New mutations in the mycobacterial ATP synthase: new insights into the binding of the diarylquinoline TMC207 to the ATP synthase C-ring structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2326–2334. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06154-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andries K, Villellas C, Coeck N, Thys K, Gevers T, Vranckx L, Lounis N, de Jong BC, Koul A. 2014. Acquired resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to bedaquiline. PLoS One 9:e102135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrella S, Cambau E, Chauffour A, Andries K, Jarlier V, Sougakoff W. 2006. Genetic basis for natural and acquired resistance to the diarylquinoline R207910 in mycobacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2853–2856. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00244-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preiss L, Langer JD, Yildiz Ö, Eckhardt-Strelau L, Guillemont JE, Koul A, Meier T. 2015. Structure of the mycobacterial ATP synthase Fo rotor ring in complex with the anti-TB drug bedaquiline. Sci Adv 1:e1500106. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biuković G, Basak S, Manimekalai MSS, Rishikesan S, Roessle M, Dick T, Rao SP, Hunke C, Grüber G. 2013. Variations of subunit ε of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis F1Fo ATP synthase and a novel model for mechanism of action of the tuberculosis drug TMC207. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:168–176. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01039-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Kessel JC, Hatfull GF. 2007. Recombineering in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Methods 4:147–152. doi: 10.1038/nmeth996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hotra A, Suter M, Biuković G, Ragunathan P, Kundu S, Dick T, Grüber G. 2016. Deletion of a unique loop in the mycobacterial F-ATP synthase γ subunit sheds light on its inhibitory role in ATP hydrolysis-driven H+ pumping. FEBS J 283:1947–1961. doi: 10.1111/febs.13715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. 2003. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol 48:77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreira W, Ngan GJ, Low JL, Poulsen A, Chia BC, Ang MJ, Yap A, Fulwood J, Lakshmanan U, Lim J, Khoo AY, Flotow H, Hill J, Raju RM, Rubin EJ, Dick T. 2015. Target mechanism-based whole-cell screening identifies bortezomib as an inhibitor of caseinolytic protease in mycobacteria. mBio 6:e00253-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00253-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stover CK, De La Cruz VF, Fuerst TR, Burlein JE, Benson LA, Bennett LT, Bansal GP, Young JF, Lee MH, Hatfull GF, Snapper SB, Barletta RG, Jacobs WR, Bloom BR. 1991. New use of BCG for recombinant vaccines. Nature 351:456–460. doi: 10.1038/351456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diacon AH, Pym A, Grobusch M, Patientia R, Rustomjee R, Page-Shipp L, Pistorius C, Krause R, Bogoshi M, Churchyard G, Venter A, Allen J, Palomino JC, Marez TD, van Heeswijk RPG, Lounis N, Meyvisch P, Verbeeck J, Parys W, de Beule K, Andries K, McNeeley DF. 2009. The diarylquinoline TMC207 for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 360:2397–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]