Abstract

This paper explores shifts in public and private delivery over time through an analysis of Ontario’s approach to LTC funding and regulation in relation to other jurisdictions in Canada and abroad. The case of Ontario’s long-term care (LTC) policy evolution – from the 1940s until early 2013 -- shows how moving from compliance to deterrence oriented regulation can support consolidation of commercial providers’ ownership and increase the likelihood of non-profit and public providers outsourcing their management.

Keywords: long-term care, nursing homes, regulation, commercialization

Introduction

“The core of the problem is that the present [long-term care] system was never planned; it has simply evolved”.i This statement was made by Richard O’Donnell in June 1983 who was then the president of the for-profit nursing homes’ lobby group known as the Ontario Nursing Home Association (ONHA). If we consider delivery, regulation and funding together, then in one sense he was correct: a clear public delivery role in Ontario’s long-term care (LTC) sector had been lacking. However, in another sense he was absolutely wrong, as definitive regulatory and funding shifts had guided the sector’s evolution in terms of its size and ownership configuration.

This paper explores shifts in public and private delivery over time by comparing the size and composition of Ontario’s LTC sector with that of British Columbia, Alberta and Manitoba using Statistics Canada data. It also analyses changes to Ontario’s approach to LTC funding and regulation and discusses the implications of its policy trajectory for other jurisdictions in Canada and abroad. The case of Ontario’s long-term care (LTC) policy evolution – from the 1940s until early 2013 -- shows how moving from compliance to deterrence oriented regulation can support consolidation of commercial providers. A deterrence regulation paradigm involves very formal rules, measurement-oriented regulations, legal remedies, punitive damages and sanctions. It assumes that organizations will break rules and try to get away with it. In contrast, a compliance regulation paradigm involves more informal rules, with regulators acting in a more supportive role by trying to develop organizations and choosing to sanction only in cases of last resort. This latter model assumes a partnership between organizations and policy makers. In step with the advent of new public management and the adoption of a deterrence oriented regulatory regime, the large for-profit commercial sector has gained and maintained ascendency in comparison with small for-profit, charitable and municipally run homes. The formula -- more deterrence-oriented regulation equals ownership and management consolidation – is like dancing the “two-step”. One partner leads the other in taking two quick steps and then two slow steps around the dance floor. Ontario’s LTC policy history shows how within Ontario’s liberal welfare state and its new public management structure, policy makers’ took leading “steps” towards deterrence regulation that were followed in lockstep by the LTC sector’s increased commercial ownership and management consolidation.

Following the methodology and methods section, this paper highlights studies querying links between care delivery ownership models and quality, and those that explore the nature of LTC regulation and care delivery organization. The third section presents findings that compare ownership trends within selected provinces and for Canada overall. Section four outlines Ontario’s LTC system’s regulatory and funding trajectory. This section is further sub-divided into four main periods: minimal regulation with private provider proliferation (1940 to 1966); the expansion of the province’s funding and regulatory role (1966 – 1993); ministerial consolidation, funding parity and the shift to medicalized long-term care (1993 – 2007); and regulatory rigidity, austerity and commercial consolidation (2007 – present). During each of these time periods, a seminal policy was passed: the Nursing Homes Act (1966) the Extended Care Funding Plan (1972); the passage of Bill 101 (1993) and its funding envelope system; and the Long-term Care Act (2007). Each marked a critical regulatory juncture that first supported, then solidified and finally concentrated chain providers’ hegemony over the long-term care sector. The paper’s final section highlights how private organizations -- notably large chain providers -- benefited most from steady public funding, provincial disengagement with public care delivery, and the public funding of private delivery. It also shows how the province’s early hesitancy to regulate was replaced by the erection of increasingly high regulatory barriers to entry as well as very medical and complex care documentation systems. The paper discusses how regulations can shape ownership patterns and explores in what ways ownership and management of LTC delivery matters, particularly when growing numbers of non-profit organizations are being managed by for-profit chains (FPC).

Methodology & Method

The analysis uses political economy assumptions that politics and economics are “enmeshed” and “integrally linked”, and that the form of capitalism underpins relations between the state, for-profit and non-profit actors, individuals and families.ii Using an historical neo-institutionalist method iii, iv, v the paper analyses critical policy junctures to explain the current ownership and management configurations between public, for-profit and non-profit organizations. The following secondary data sources were triangulated: comparative provincial data of ownership of facilities and beds from the Statistics Canada Residential Care Facilities Survey (1984 – 2010); the Ministry of Health and Long-term Care (MOHLTC) online database “Reports on Long-Term Care Homes”vi to establish the initial Ontario facilities list; annual reports of public for-profit long-term care companies (SEDAR and EDGAR databases); journal articles; the Ontario Long-Term Care Association Directory (2012); newspaper articles; business databases; and the websites of the owners and management firms providing long-term care services.

Commercial Delivery of Care

There is a well-developed literature addressing the compatibility of for-profit ownership with quality care. Staffing intensity, which is a measure of the staff to resident ratio, is considered by some to be the single most important factor affecting work organization, working conditions and quality of care in long-term residential care.vii, viii Canadian research has documented how municipal and nonprofit homes typically operate with a higher staff to resident ratio while for-profits more often staff minimally.ix, x, xi

Studies show how, at an aggregate level, commercial provision of care has had negative quality implications. McGregor and colleagues have demonstrated that for–profits tend to average worse performance on clinical quality measures than non-profit and publicly operated facilities.xii Three systematic reviews have also explored the LTC ownership relationship to clinical quality measures: Davis found an inconclusive linkxiii; Hilmer and colleagues found that non-profit facilities outperform and provide better care than for-profit ones on important process and outcome measuresxiv; and Commodore and colleagues reviewed studies from 1965 to 2003 and found that nearly half favoured non-profit care, three favoured for-profit care and the remainder lacked consistent findings leading the authors to conclude that, when averaged, non-profit homes provide care of higher quality than for-profitsxv.

While some of the quality of care debate has centred around ownership patterns and staffing levels, the emergence of new hybrid organizational forms, with non-profits being managed by for-profits, raise important questions about what it means to be a non-profit if management decisions use a for-profit market model. While there are no studies exploring this in Canada, Kaffenberger has shown that in the United States, for-profit ownership composition has changed dramatically since the Medicare and Medicaid programs were put in place in 1965.xvi By 2008 the American LTC sector had shifted away from having small homes and non-profit providers to large for-profit chains (FPC). The adoption of new ownership, management and financing strategies that include non-profit companies amongst FPC in the United States and United Kingdom have reduced chain providers’ liability, their payment of taxes, and increased the rates of bankruptcies.xvii, xviii, xix Some deleterious impacts of complete divestment of public facilities to non-profit or for-profit ownership -- such as more regulatory violations, and negative consequences for residents’ quality of life -- have been documented.xx As Stevenson and colleagues have argued, “…knowing the proprietary status of a nursing home provider is insufficient to discern how organizational assets are structured and the operational approach of the company managing the delivery of nursing home services.” xxi So, while the literature points to a tendency at the aggregate level for there to be higher levels of staffing and higher quality of care in non-profits on some outcome measures, how we interpret poor performance on clinical and performance quality measures when a large and growing proportion of non-profit beds are managed by for-profits has yet to be addressed. Indeed, the phenomenon is so new that the literature is silent on it.

Finally, to what extent does regulatory complexity drive commercialization and consolidation? According to Walshe, states can choose three main regulatory routes: deterrence, compliance and responsive regulation. The LTC sector in the United States has been at the forefront of opting for deterrence regulation.xxii The regulatory burden organizations face as a result of the deterrence model may lead to greater commercialization; since the adoption of the United State’s Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) 1987, major chains have increasingly dominated the sector.xxiii Because of the large, fixed costs of regulation, larger organizations may be able to spread the costs over a much greater business volume as well as to develop capacity in regulatory compliance skills. Single-site, owner operated businesses and non-profit organizations may find it hard to compete in a heavily regulated environment.xxiv Thus, with heavily regulated, deterrence oriented environments one might expect concentration of LTC delivery and management within larger, chain organizations; this relationship is explored in this paper.

The Context: Comparing Commercial Consolidation of Long-term Care

This section delineates the sector’s concentration of power, focused on the number and size of players involved in the LTC delivery, comparing Ontario to three other provinces: B.C., Manitoba, and Alberta. The data are divided by ownership. There are three types of privately owned homes. Proprietary homes are run by for-profit companies that are either single homes or part of for-profit chains. Non-profit religious homes are run by religious organizations and may be stand-alone or linked to another home, but typically to no more than one. Non-profit lay homes are secular and like non-profit religious homes are usually stand-alone but may include more than one home. Public homes are either municipally run and their employees are municipal government staff, or provincially owned and staffed. This section shows that while commercial consolidation has been most evident in Ontario, and the public sector is most expansive outside of Ontario, nonetheless each of the other provinces resemble Ontario in specific ways.

Table 1 shows that there were more proprietary providers operating in 2010 when compared with 1984 both across Canada and within Ontario and Alberta. In contrast, there were fewer in B.C. and Manitoba. Commercialization was most widespread in Ontario with respect to the percentage share of the sector owned by proprietary operators at points in time. In B.C. more than five in ten were owned by proprietary operators in 1984, compared with little more than four in ten homes by 2010. In Manitoba, Alberta, and B.C. had the highest percentages of public facilities in 2010 with between one third and one-quarter of the homes. The number of publicly-owned homes in these three provinces was about twice as big as in Ontario, where only one-sixth of homes were municipally owned; the other provinces did not have any municipal homes, and Ontario remained the only one of the group without a provincial ownership role. In Alberta provincial investment followed a substantial divestment by the municipalities, which previously had owned forty per cent of homes. Despite the increased provincial role, this shift in Alberta reflects one in favour of privatization because commercial and non-profit providers there played a more expansive role than before. In contrast to Ontario, non-profits in B.C., Manitoba and Alberta played a larger though declining role over time. And, despite Manitoba’s strong public sector role, there was a larger share of commercial owners and a decline in non-profit lay ones by 2010.

Table 1.

Number of Residential Homes for the aged facilities by Ownership Type, 1984 – 2010 xxv

| Proprietary | NP Religious | NP Lay | Municipal | Provincial | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 1984/1985 | 1085 | 155 | 306 | 271 | 34 |

| % | 58.6% | 8.4% | 16.5% | 14.6% | 1.8% | |

| 2009/2010 | 1145 | 157 | 314 | 132 | 291 | |

| % | 56.2% | 7.7% | 15.4% | 6.5% | 14.3% | |

| Ontario | 1984/1985 | 416 | 42 | 61 | 90 | 4 |

| % | 67.9% | 6.9% | 10.0% | 14.7% | 0.7% | |

| 2009/2010 | 482 | 39 | 108 | 104 | 5 | |

| % | 65.3% | 5.3% | 14.6% | 14.1% | 0.7% | |

| Alberta | 1984/1985 | 36 | 15 | 9 | 43 | 0 |

| % | 35.0% | 14.6% | 8.7% | 41.7% | 0.0% | |

| 2009/2010 | 78 | 39 | 24 | 0 | 58 | |

| % | 39.2% | 19.6% | 12.1% | 0.0% | 29.1% | |

| BC | 1984/1985 | 178 | 14 | 117 | 1 | 4 |

| % | 56.7% | 4.5% | 37.3% | 0.3% | 1.3% | |

| 2009/2010 | 123 | 22 | 68 | 0 | 68 | |

| % | 43.8% | 7.8% | 24.2% | 0.0% | 24.2% | |

| Manitoba | 1984/1985 | 32 | 23 | 40 | 28 | 1 |

| % | 25.8% | 18.5% | 32.3% | 22.6% | 0.8% | |

| 2009/2010 | 27 | 17 | 17 | 0 | 29 | |

| % | 30.0% | 18.9% | 18.9% | 0.0% | 32.2% |

Statistics Canada. Table 107-5501 (accessed: September 24, 2013)

The highest percentages for each category are highlighted in grey.

With the average home size increasing over time, we must focus not only at the number of homes but also at bed concentration by ownership category. Table 2 shows that across Canada, bed numbers grew at a stellar rate in the provincial category (570.5%), and declined (32.1%) in the municipal one. There was significant growth in the number of proprietary owned beds (54.6%). These growth trends reflect a shift to greater provincial ownership in all of the studied provinces but Ontario, a divestment of municipal beds in all of the provinces but Ontario, and a tremendous increase in the beds owned by the proprietary sector in Ontario (63.2%), Alberta (89.2%) and B.C. (47.4%). Manitoba is the sole standout registering a decline (−3.2%). Ontario and Alberta experienced growth to non-profits’ share of bed ownership; the growth was sometimes stellar, while the actual number of beds remained comparatively quite small.

Table 2.

Number of Residential Care Beds by Ownership Type and by jurisdiction 1984 – 2010 65

| Proprietary | NP Religious | NP Lay | Municipal | Provincial | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 1984/1985 | 61100 | 13863 | 25104 | 28029 | 3764 |

| 2009/2010 | 94482 | 15616 | 30292 | 19030 | 25236 | |

| % Growth | 54.6% | 12.9% | 20.7% | −32.1% | 570.5% | |

| Ontario | 1984/1985 | 32810 | 4250 | 6013 | 17785 | 868 |

| 2009/2010 | 53587 | 4953 | 13220 | 17014 | 311 | |

| % Growth | 63.2% | 16.5% | 119.9% | −4.3% | −64.2% | |

| Alberta | 1984/1985 | 3606 | 1414 | 778 | 2875 | 0 |

| 2009/2010 | 6831 | 3042 | 2777 | 0 | 6147 | |

| % Growth | 89.4% | 115.1% | 256.9% | −100% | - | |

| BC | 1984/1985 | 6995 | 1217 | 10159 | 76 | 421 |

| 2009/2010 | 10313 | 2429 | 6593 | 0 | 7518 | |

| % Growth | 47.4% | 99.6% | −35.1% | −100% | 1685.7% | |

| Manitoba | 1984/1985 | 2716 | 2058 | 2680 | 969 | 185 |

| 2009/2010 | 2629 | 1795 | 1589 | 0 | 3669 | |

| % Growth | −3.2% | −12.8% | −40.7% | −100.0% | 1883.2% |

Statistics Canada. Table 107-5501 (accessed: September 24, 2013)

The percentage growth is highlighted in grey.

While the absolute number and the growth in beds reveal important shifts, the distribution of beds across ownership categories is also very important to consider (Table 3), as it shows the relative balance between the for-profit, non-profit and public sectors. Two main models appear: most beds owned by the proprietary sector, and most beds owned by the public sector. In Ontario, Alberta and B.C, the proprietary sector owns the most beds. Manitoba is the sole stand-out, with most beds publicly held. An evenly balanced sector would have approximately thirty-three percent allocated to each of the sectors. Manitoba is weighted on one side with higher public sector investment in bed ownership and Ontario, B.C. and Alberta on the other with higher proprietary bed ownership investment. Although tipped in favour of the proprietary sector, Alberta comes closest to a balance. When it comes to a public private balance, Ontario is the most commercialized, but not a complete outlier as in the previous tables. However, though there is strong commercial ownership across Canada, other provinces have also substantially increased their provincial public sector role, something that has not been done in Ontario, where homes are still municipally owned. In addition, Ontario has fewer non-profit beds compared with the distribution common across Canada.

Table 3.

Comparative Distribution of Residential Beds by Ownership Type, 1984 – 2010 *65

| % Proprietary | % NP Religious | % NP Lay | % Municipal | % Provincial | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 1984/1985 | 46.3% | 10.5% | 19.0% | 21.3% | 2.9% |

| 2009/2010 | 51.2% | 8.5% | 16.4% | 10.3% | 13.7% | |

| Ontario | 1984/1985 | 53.2% | 6.9% | 9.7% | 28.8% | 1.4% |

| 2009/2010 | 60.2% | 5.6% | 14.8% | 19.1% | 0.3% | |

| Alberta | 1984/1985 | 41.6% | 16.3% | 9.0% | 33.1% | 0.0% |

| 2009/2010 | 36.3% | 16.2% | 14.8% | 0.0% | 32.7% | |

| BC | 1984/1985 | 37.1% | 6.5% | 53.8% | 0.4% | 2.2% |

| 2009/2010 | 38.4% | 9.0% | 24.6% | 0.0% | 28.0% | |

| Manitoba | 1984/1985 | 31.6% | 23.9% | 31.1% | 11.3% | 2.1% |

| 2009/2010 | 27.2% | 18.5% | 16.4% | 0.0% | 37.9% |

Statistics Canada. Table 107-5501 (accessed: September 24, 2013).

Numbers may not add to 100 due to rounding

The highest percentages for each category are highlighted in grey.

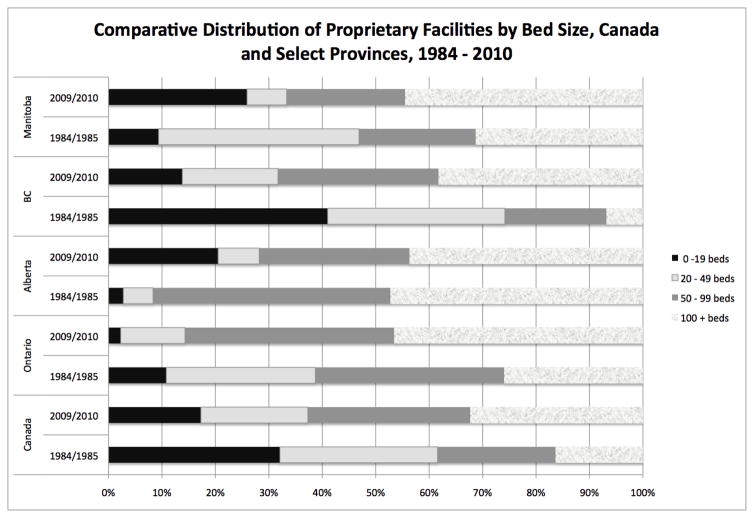

Home size measured by the number of beds is another important metric because having larger homes each with more beds can consolidate power to fewer players and translate into economies of scale thus furthering consolidation trends. We consider fewer than 19 beds to be very small, between 20 and 49 to be small, 50 to 99 beds to be medium in size and 100 and more to be large. The data show that by 2010 in all of the provinces studied the majority of proprietary sector homes were large ones (Ontario, Manitoba and B.C.). In 1984, Canada’s and B.C.’s proprietary sectors were mostly very small homes, Manitoba’s were mainly small, Ontario’s were largely medium sized homes and in Alberta there was an even spread between most homes being either medium or large. The size of home metric reflects a significant change in the composition of the proprietary sector between 1984 and 2010 from very small, small and medium homes to large homes. It shows that small proprietary homes comprised a shrinking proportion of for-profit ones overall. Despite the similarities, Ontario still stands out. By 2010, the number of Ontario’s proprietary 100 + bed homes almost doubled. When compared with the other jurisdictions, the largest proportion of large homes are in Ontario. In addition, the province has far fewer small homes than do the other provinces.

Ontario is the most commercialized in terms of the number of providers and the number of beds. The province is also more consolidated in that it has a higher number of large commercially owned homes. In order to better understand the origins of the commercialization and consolidation trends, the next section analyses Ontario’s LTC regulation and the public and private sector roles over time.

Regulation of Long-term Care in Ontario (1940s – 2013)

This section delineates four regulatory phases starting in the 1940s. The first involved the expansion in the number of private providers (1940 to 1966). The second phase -- from 1966 to 1993 -- was defined by the expansion of the public funding and regulatory role but also by a lack of policy coordination within government. The third phase lasted until 2007 and involved Ministerial consolidation and the introduction of funding parity between for-profit, non-profit and public homes. It also involved the expansion of public capital funding, which further solidified the hegemony of for-profit chain (FPC) providers. Finally, following a series of sensational media exposés, in a climate of public sector austerity, the state erected complex regulatory and reporting requirements that have served as high barriers to entry, and have resulted in further commercialization and consolidation of the ownership and management of the sector favouring FPC (2007 – present).

Private provider proliferation (1940–1966)

The public was slow to address the need for residential elderly care. The first public municipal home for the aged was officially opened in 1949 and housed seven hundred residents. The clientele was younger, less affluent and more ambulatory compared with the population in long term care homes today. This was in keeping with the original mandate of homes for the aged, which focussed on “the poor, not the sick elderly”.xxvi By the early 1950s, long wait lists to live at the facility had developed.

As James Struthers has shown, the commercial provision of nursing home care proliferated in the early 1940s. xxvii Calling it an “unintended partnership of convenience” he argued that it started as an interim emergency measure by the City of Toronto when they began to discharge older welfare recipients from hospitals.xxviii The City paid selected privately owned nursing homes forty dollars per month per resident. Over the next two decades, the need for residential care outside hospitals was increasingly filled by for-profit providers.

An influx of federal unemployment assistance funding starting in 1959 meant that the province absorbed eighty per cent of the direct costs of housing elderly welfare recipients in private nursing homes- thus relieving municipalities of the ballooning costs of doing so and exponentially expanding the private nursing home sector.xxix But, poor conditions in some private nursing homes led the provincial government to respond with a few public alternatives. In the 1950s and 1960s, seventy modern homes for the aged were built or renovated by municipalities with provincial cost-sharing to replace the public “houses of refuge” or “county poorhouses” that had previously housed poor and indigent elderly people.

Regulation developed slowly and haphazardly despite the great need for it. For instance, by the mid 1940s the number of elderly people the City of Toronto supported to live in private nursing homes had swelled from thirty to more than six hundred people. These boarding and payment arrangements were largely without licensure or inspection until a symbolic City of Toronto by-law enacted in 1947 specified how many people could reside in the home, how facilities were to be shared and used by visitors, and what were the buildings’ sanitation and safety codes.xxx In the 1950s the province drafted a “model bylaw” for municipalities’ use to license and inspect private nursing homes, but the by-law did little more than ensure that inspection remained local and that higher provincial costs for oversight and compliance were avoided.xxxi, These regulatory methods proved largely ineffectual. By 1957 there were only twelve municipalities that engaged in any sort of private nursing homes’ licensure, and it was often little more than bureaucratic oversight. The move did little to address complaints of poor conditions, anomalous death rates and poor care that plagued some nursing homes. Even many in the private sector agreed that conditions in some homes were appalling. Following the “First Ontario Conference on Aging” in 1957 the Ontario Welfare Council (OWC) aided the 150 plus operators of private nursing homes to form the Associated Nursing Homes Incorporated of Ontario (ANHIO).xxxii With different motivations these two groups lobbied the provincial government to fund, regulate and license private nursing homes.

Expansion of Public Regulation & Funding (1966 – 1992)

Thus, amidst reports of private nursing home abuses the Ontario Nursing Homes Act, 1966 was passed to legislate for-profit care providers. The Act set standards for medical and nursing care and the physical plant including housekeeping and maintenance. It did not provide provincial funding directly to facilities, but maintained a regional system with municipalities receiving the funding and retaining responsibility for regulation and inspection. Struthers noted the Act: “cemented an uneasy partnership between private enterprise and the Department of Health to ensure that profitability could be reconciled with Ontario’s burgeoning fiscal priorities as well as with the long-term care needs of the elderly”.xxxiii Privately-owned nursing homes remained small during the post-war period; even by the mid-1960s two-thirds of Ontario nursing homes had no more than twenty beds. However, the number of private sector beds grew enormously following licensure and regulation in 1966, from 8500 to 18,200 beds by 1969.xxxiv By the late 1960s the system remained predominantly private for-profit in terms of delivery but public in terms of funding. Nearly two-thirds of residents received public subsidy from the welfare departments or from the Ontario Hospital Insurance Commission.xxxv

Health officials found that the private nursing homes lobbied for continual rate increases while returning as little as they could back to the patients.xxxvi In response, by the mid-1960s, welfare officials warned that the public system needed to build more places for elderly people in order to improve conditions and thwart an over-reliance on commercial facilities. The Rest Homes Act, 1966 allowed for 50 percent capital and 70 percent operating funding to municipalities to fund and administer public rest homes (distinct from homes for the aged). But, by the late 1960s, the province had built only two of these. In addition, by 1965 due to a lack of capacity in for-profit nursing homes and hospital bed shortages, about half of the beds in the homes for the aged (45%) were allotted for, more complex “bed care” (what would become known as “extended care” in 1972) even though all beds in homes for the aged were intended to provide custodial care, that is, basic assistance such as washing, dressing and cooking. xxxvii

Over time, regulatory standards increased. For instance, the Nursing Homes Act was amended in 1972 to include standards for the physical plant, medical care, staffing intensity, activation, the dispensation of medications and record keeping. To ensure compliance, inspectors were hired to work in field regional offices. An inspection program was housed within the Institutional Division of the Ministry of Health. The inspection process was quite local; a manual to guide the inspection process was not produced until 1992, so regional differences of interpretation persisted throughout this period.xxxviii

Ontario’s private delivery, public funding medicalized model was entrenched with the 1972 passage of the Extended Care Plan. It publicly funded residents with medical care needs; it required nursing homes to provide at least one and a half hours of skilled nursing and personal care per resident per day funded through the Ministry of Health. This form of funding was criticized for not rewarding a home for providing more than a minimum level of care. Following provincial public funding in 1972, the for-profit industry grew quickly. It went from “small, single operator dwellings” of 20 beds that were largely owned by women to “highly profitable, modern one-hundred to two-hundred-bed facilities, owned by corporate chains earning up to 15 percent rates of return for investors and dedicated to…make money for shareholders”.xxxix

During this period, many arguments were made regarding funding fairness. Despite growth in the number of for-profit providers, funding levels tended to favour public and non-profit homes governed by the Homes for the Aged Act and the Charitable Institutions Act. Unlike the nursing homes which operated under the Ministry of Health, for these other institutions, the funding model followed a “deficit funding” budget based system; 70 per cent of the funding came from the provincial Ministry of Community and Social Services and 30 per cent from the municipalities with any deficits covered by governments according to their allotted 70/30 budget share.xl The Ontario Association of Homes for the Aged argued that deficit funding allowed for “flexibility” in keeping with providing care in a way that met the needs of the individual and of the community.xli This funding model would remain in place until 1993, the year when homes for the aged were brought under the umbrella of the newly formed Ministry of Health and Long-term Care (MOHLTC). The Extended Care Plan meant that private for profit nursing homes were funded differently than municipal homes for the aged. While homes for the aged (both municipal and charitable) were originally charged with providing custodial care, approximately half of the beds in homes for the aged were classed as extended care beds.xlii The ONHA argued that funding differences favoured municipal and charitable homes able to draw on both deficit funding and extended care per diems.xliii In addition, charitable homes could use donations to provide more care or renovate. But for-profit homes benefited in other ways. Because of a tendency to have more semi-private and private rooms, private homes could generate extra funds. Forbes argued that bed allocations in municipal homes were largely based on need, meaning that a private room did not amount to a true revenue stream for municipal homes like it did in private homes.xliv

By 1986 the Ontario Select Committee on Health showed that there was a preference for nonprofit applicants in the public tender of nursing homes. This trend was slowly eroded and then reversed a decade later. Despite contemporaneous arguments that long-term care should be done in non-profit facilities, Tarman’s analysis -- based on key informant interviews with Ministry representatives -- showed corporate for-profit chains (FPC) increased their ownership stake of the sector to 50.9% of the facilities and 42.2%of the beds (Table 4).xlv By 1989, 35% were regulated as homes for the aged. The remaining 65% were legislated by the Ontario Nursing Homes Act (1972, 1987). Tarman’s findings were confirmed by a 1992 study that also used Ministerial data;xlvi however, the numbers differ from the sectors’ self-report data gathered for the Statistics Canada Residential Care Facilities Survey (Tables 2–5).

Table 4.

Ownership Distribution in the Long-term Care Sector, 1989 42

| Regulatory Classification | Homes for the Aged | Nursing Homes | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home Ownership | Municipal | Charitable | Corporate for-Profit | Independent | Municipal | Charitable | Lay | Hospitals | Indian Bands | |

| Facilities | 89 | 93 | 264 | 29 | 3 | 12 | 11 | 16 | 2 | 519 |

| % Facilities | 17.1% | 17.9% | 50.9% | 5.6% | 0.6% | 2.3% | 2.1% | 3.1% | 0.4% | 100% |

| Beds | 27,968 | 24,542 | 3,191 | 154 | 702 | 729 | 723 | 110 | 58,119 | |

| % Beds | 48.1% | 42.2% | 5.5% | 0.3% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.2% | 0.2% | 100% | |

| % Extended Care Beds | 47% | Approximately 94% | n/a | |||||||

Table 5.

Distribution and Proportion of Ontario Long-term Care Home and Beds by Ownership and Management

| Owned Homes | Managed Homes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership Type | # Homes | % Total Homes | # Beds | % Total Beds | # Beds FPC Manage d by Location | Distribution of FPC Managed Beds by Location of Ownership | % FPC Managed Beds by Location of Ownership | ||||

| FPC | 285 | 360 | 44.3% | 56.0% | 34,480 | 41,353 | 44.1% | 52.9% | 5,660 | 58.0% | 13.7% |

| FPI | 75 | 11.7% | 6873 | 8.8% | |||||||

| Non-profit | 101 | 15.7% | 12,022 | 15.4% | 2,636 | 27.0% | 21.9% | ||||

| Charitable | 51 | 7.9% | 7,207 | 9.2% | 699 | 7.2% | 9.2% | ||||

| Non-profit Hospital | 13 | 2.0% | 758 | 1.0% | 265 | 2.7% | 35.0% | ||||

| Municipal | 103 | 16.0% | 16,535 | 21.1% | 498 | 5.1% | 3.0% | ||||

| ELDCAP | 15 | 2.3% | 335 | 0.4% | 0 | 0% | 0 | ||||

| Total | 643 | 100.0% | 78,210 | 100% | 9,758 | 100% | 100% | ||||

Analysis of Ministry of Health and Long-term Care (MOHLTC) provider list, association directories, newspaper and web searches

In 1982 ONHA hired an accounting firm to argue for more funding for “heavy care” residents. They also worked with a 1986 Ministry of Health committee to develop a Resident Assessment Classification System.xlvii Both initiatives foreshadowed funding model changes implemented a decade later. In 1986 the province introduced a special “enhancement funding” strategy, which tied specific per resident per diem funding increases to accreditation, the delivery of particular services, the conduct of in-service training, and/or the hiring of particular staff. This special program funding model prompted the ONHA president Mel Rhinelander to remark: “[o]n their own, these initiatives may not seem significant. However, the radically new method of special program funding provides us with unlimited possibilities for seeking support for new services…”xlviii Indeed, these initiatives signalled the province’s future intentions to initiate targeted funding schemes tied to initiatives or homes’ compliance.

In summary, during this period the Ministry of Health began regulating commercial providers of LTC. Although some non-profit and municipal homes began to provide “nursing home” levels of care the period was largely defined by the continued separation of nursing homes providing more complex and medically oriented care, and homes for the aged providing custodial care. It was also marked by the adoption of increasingly sophisticated regulatory tools to control the behaviour of the homes. Still, the municipal and non-profit homes that provided custodial and nursing home care were entitled to access more public funds. This funding parity issue would partly define the next period.

Ministerial Consolidation, Funding Parity and Containment (1993 – 2007)

The ONHA’s main goal of funding parity was realized seven years later with the 1993 passage of Bill 101: homes for the aged were brought under the Ministry of Health funding formula; the formula was tied to a classification system based on the complexity of residents’ needs in a given home compared against an averaged Case Mix Index; and funding parity was established between all nursing homes and homes for the aged. In addition, Bill 101 eliminated the extended care funding, initially dispensed with minimum staffing requirements, and introduced a new envelope system that standardized provincial funding of for-profit nursing homes with that for non-profit and municipal homes for the aged. The envelopes for nursing and personal care included care staff and supplies; program and support services included therapy, pastoral care, recreation and volunteer coordination; and accommodation included raw food, housekeeping, laundry, dietary, administration and building upkeep and maintenance. The model was roundly criticized by homes for the aged as it replaced public and non-profit homes’ global funding I with a constrained envelope model that favoured managing well only by following rules..

During this same period, the original Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement was re-negotiated to include Mexico as signatory in a new North American Free Trade Agreement (1994). Long term care was explicitly included in the agreement’s terms. This served to cement the commercial model in long-term care because LTC was contained as a substantive clause. This meant that it was subject to none of the provincial Annex 1 reservations signed in 1996 that exempted social services from the terms of the agreement.

Following the introduction of the envelope model, the ONHA lobbied government to adopt interim measures to add more funding. The first, and perhaps most important interim measure, was level of care funding. Starting in 1994, the Ministry of Health and Long-term Care (MOHLTC) seconded specially trained nurses to conduct chart reviews of all 57,000 residents in LTC to establish a home’s Case Mix Measure (CMM) based on the Alberta Resident Classification System. The CMM of all homes were grouped to create a Case Mix Index. This was used by the government to establish a baseline average value of “100”. If a home scored higher/lower than 100, it was funded at a higher/lower level as a reflection of the needs of its resident population. Since nursing homes had cared historically for “heavier care” residents, this tool immediately increased nursing homes’ funding. Its use would eventually aid the Ministry in shifting the orientation of the whole sector towards higher medical acuity. Although the Case Mix Index was supposed to determine the amount of nursing and personal care funding destined for a given facility, advocacy by health care unions ensured that the government maintained a 2.25 hour minimum staffing standard, and delayed the implementation of level of care funding until an election shifted power to the Progressive Conservative party in 1996. Following the election, minimum staffing requirements were eliminated in facilities across Ontario, freeing homes to alter staffing ratios. A second interim measure was a system of red circling that ensured that municipal homes’ funding would not drop immediately in 1993, but would be maintained until the whole sector came on par with municipal homes’ funding levels. This system was also eliminated in 1996 under the Conservative government, but a “high wage transition fund” was established between 1996 and 1999 to aid all facilities that paid higher than average wages. A third interim measure, involved the government funding ninety percent of the previous year’s business and realty taxes. Because nursing home operators that had purchased, rebuilt or refinanced homes faced insolvency, the government established a $11 million debt servicing fund in 1993. It remained operational until 2002. To fund these measures, the government started to claw back half of the income generated by facilities’ preferred accommodation funding beginning in 1993.xlix The ONHA argued that the for-profit sector’s credibility was enhanced with an “equitable funding system in place” and the elimination of profit-taking in the nursing and personal care envelope. In theory, the new special program funding focus meant that facilities could start new programs to enhance quality of life.

Like previous governments, the Harris conservatives sought to put their own stamp on long-term care. In May 1998, they announced an investment of $1.2 billion for home care and long-term care facilities to be partly used to create 20,000 new long-term care beds across the province by 2006 and to upgrade an additional 16,000 existing beds in about 102 of the structurally non-compliant facilities. To start, guaranteed increases were promised for the nursing and program envelopes. What was not clear at the time was that this capital investment amount would balloon to $1.5 billion by 2003, and that the capital costs would come out of annual Ministerial operating funds for the coming two decades. In the process of expanding the sector, historical capital funding privileges for municipal homes were eliminated. Prior to 1998, municipal homes could access 50 percent capital grants from the provincial government. For-profit homes had been excluded from this program. Once the tenders were announced, two thirds of the new beds were allotted to the for-profits, with Extendicare, Leisureworld and CPL REIT building 39.5 percent of them. Capital costs of the building spree were publicly funded. New or refurbished beds were subject to an extra $10.35 per bed per day subsidy from the provincial government to cover capital costs for 20 years after which homes remain the capital assets of the organizations. This increased funding to $75,555 per bed over 20 years to offset capital construction costs for newly-built or retrofit facilities.l The newly built homes were much larger with more beds. In addition, the balance of shared and private accommodation shifted; operators were allowed to designate as many as sixty per cent of these new beds as private accommodation for which residents had to pay an extra daily accommodation fee to the organization. The Harris government agreed to increase the co-payments paid for preferred accommodations by 15 per cent by 2005, and to waive the claw back on preferred accommodation funding, thus returning potential profits/surplus back to operators. This amounted to a complete reversal of earlier approaches.

In summary, the shifts during this period represented a fundamental departure from the past. The role of long-term residential care was firmly cemented in the medical care system with the shift to a case mix formula for funding that rewarded the care of more medically complex individuals. The hegemony of the commercial sector was solidified by implementing funding parity with homes for the aged and adopting a measure of complexity already supported by the large for-profits. Debt servicing of for-profit operators was established. Finally, the capital infrastructure privilege to municipal homes was not only eliminated but shifted in favour of chain providers.

Regulatory Parity, Austerity and Commercialization (2007 – present)

With the rapid building expansion concluding, the government shifted its focus. To match its previous efforts around funding parity, the province enacted regulatory and compliance parity between commercial, non-profit and public providers by merging three legislative Acts. It also implemented a form of austerity since costly, newly built and renovated publicly funded beds were not staffed sufficiently. Finally, it adopted an unbalanced growth strategy that served to further the sector’s commercial consolidation.

Regulatory parity was achieved with three policy initiatives. The passage of the Long Term Care Act (2007) in 2010 initiated regulatory parity, and followed the provincial path pursued in 1993 when funding parity was established. Three separate pieces of legislation were amalgamated: the Nursing Homes Act, Homes for the Aged and Rest Homes Act, and Charitable Institutions Act. The new Act created the same legislative framework of more than 300 regulations. The province also mandated the use of Minimum Data Set Resident Assessment Instrument (MDS-RAI) first for reporting, then for funding. Use of the former system had not sufficiently prepared homes for the new system. Homes complained that the new system was more time-consuming, more medically focussed, and less usable for day-to-day operations.li Many homes had difficulty once funding was tied to MDS in 2012 and experienced a decline in their funding. In addition, a new Compliance Transformation Project -- begun in 2008 and completed in 2012 – reframed the inspection process, such that a home “…may have had very few or no unmet standards, now has some Written Notifications along with actions/sanctions based on the severity, scope and licensee’s past history of compliance”.lii The province also erected publicly available reporting in conjunction with its stricter compliance inspection process. Taken together, these changes significantly altered the regulatory complexity of the LTC landscape.

The climate of public sector austerity in Ontario was different in LTC than in other sectors because capital funding increased by 80 per cent to $3.83 billion in 2013/2014 from a total amount of $2.12 billion in the year 2003/04,liii but much of it was used to renovate old and build new facilities. Because this capital funding will continue to show up yearly for the next 20 years, the increases have masked sector cutbacks like insufficient growth in funding for staffing. Furthermore, critics argue that insufficient operating funding does not address staffing shortages which increase the likelihood of violence from aggressive residents. liv Since 2003 the MOHLTC has expanded by 2,500 the number of full-time personal support worker (PSW) positions and by 900 the number of full-time nursing positions in long-term care homes.lv However, with 20,000 new beds added, and new reporting and compliance procedures in place, new staffing amounts to little more than 1 PSW per 8 residents on one shift per 24 hours. In addition, it is not clear if those hired were front-line care workers or administrative staff with clinical training to aid organizations to meet new regulatory and compliance criteria. Critics have cited the lack of a mandated minimum care standard in the legislation as the main outstanding issue. The 2007 legislation failed to re-establish a minimum standard eliminated by the Harris Conservative. A 2008 independent reviewlvi documented Ontario’s staffing standards at levels much lower than what experts recommend. lvii, lviii

Many have argued that the sector was highly fragmented. For instance, one chain provider noted in its Annual Report: “Leisureworld has significant opportunities for acquisitions in the fragmented LTC industry. With the regulatory burden becoming more onerous for smaller industry participants, larger companies with scale are positioned for continued growth.” lix In other words, small, independent providers were most at risk of closing or contracting out management functions. Their inability to reap economies of scale gains from bulk purchasing or from sharing back-office functions to aid adherence to reporting and data management requirements could be possible explanations for closures and consolidation.

Data were triangulated between the Ontario MOHLTC provider list, association directories, newspaper reports, and web searches to analyse the concentration of LTC players current to 2013. When ownership (the licensee) and home’s management were grouped there were: 16 major delivery and seven major management chains; 16 smaller chains that operate 2 or 3 homes; and 3 single home management firms that split a home’s ownership from its management. These firms totalled almost half of the homes operating in the province. As Table 4 showed, in 1989 when there were 519 homes and 58,119 beds the FPC controlled 264 homes (50.1%) and 24,542 beds, or four in ten (42.2%) beds.lx As Table 5 shows, by 2013, 123 more homes and just over 20,000 more publicly funded beds (total = 78,210) were added to the sector. FPC directly owned 285 homes – fewer than half of Ontario homes (44.3%) -- and 34,480 beds (44.1%) equal to the same four in ten beds. Non-profit and charitable homes together owned fewer than one quarter of the homes (15.9% and 7.9% respectively); 16 per cent were publicly owned by municipal homes, which tended to be larger and operated just over one-fifth of beds (21%). What alters the balance -- and was perhaps most surprising -- were the amount of non-profit and public beds managed by FPC. More than three of ten (31.1%) residents living in a non-profit or charitable home that were managed by a FPC. Almost four in ten residing in LTC beds in hospitals were managed by a FPC. Furthermore, more than one in ten lived in an FPI facility with contracted-out management. Since almost ten thousand more beds (12.5% of total beds) were managed by FPC, and almost half of these beds were in non-profit or public owned facilities, over half of the beds (56.6%) in the sector were owned and/or operated by FPC. Thus, FPC ownership or management of beds has grown by 80.3% between 1989 and 2013.

Like in other countries, FPC have adopted merger, acquisition, management and takeover plans.lxi, lxii Also similar is the way that FPC are organized: geographic specialization; functional line specialization; parent/subsidiary relationships; the separation of home’s ownership and management into two or more companies; contracted-out management and partnerships. There are four discernible types of FPC operating in Ontario. There are private “family run” chains, that often began as a FPI. A second type, investor-focused firms, claim access to solid, stable guaranteed income and demand in long-term care. These investor-focused firms often have outsourced the day-to-day management to a third type of chain that operates as a management firm either part of the large delivery chains or as separate management chains, both types touting administrative and managerial expertise to confront the growing regulatory complexity. Finally, the bulk of the homes are large public FPC touting their experience, access to best practices and the ability to be efficient and effective.

In sum, nearly six in ten (45,338) older adults in the province resided in beds owned or managed by a FPC. Thus FPC owned about four of every eight beds (44.3%) and managed an additional one in eight beds (12.5%) owned by a FPI, non-profit or public facility. With an expansion in the number of beds and facilities, and the increased regulatory pressures there has been considerable consolidation and concentration in the sector favouring FPC. Analysis of the ownership and management patterns in the sector provided little support for a highly fragmented sector; instead it pointed to the continued predominance of the FPC in the ownership of delivery and a significant shoring up of control within a top tier of chain firms. The patterns in Ontario seem to follow that of other countries with highly developed commercial provision of LTC. The contracting-out of non-profit and municipal homes in Ontario to FPC management has been under-explored.

Discussion & Conclusions

When comparing Canada’s provincial health care systems, the delivery and management of long-term residential care in Ontario is perhaps the most commercialized area with the possible exception of pharmaceutical manufacturing. Why is this the case? When viewed in historical context, it is clear that a commercial logic governed the development of the sector almost from the beginning of the post-war period. Past and current actions by provincial and municipal governments have resulted in few commitments to promote non-profit or public organizations compared with for-profit organizations, in spite of stated aims. For instance, this commercial logic persists today despite what is written in the preamble to the current Long Term Care Homes Act 2007: “[t]he people of Ontario and their Government…[a]re committed to the promotion of the delivery of long-term care home services by not-for-profit organizations.”

Table 6 summarizes the key macro and meso trends and regulations. In the period prior to 1966 -- before the province enacted the Ontario Nursing Homes Act -- the logic followed a pattern of commercial proliferation, with many for-profit operators opening small homes. This growing commercial logic was fuelled by for-profits’ progressively more coordinated efforts lobbying the state for funding increases, for regulatory and funding parity between for-profit and non-profit homes, and for quantitative measurement in line with New Public Management (NPM) goals. The shift to a medical orientation and the elimination of historical funding privilege to non-profit and public institutions in 1993 further solidified this trend. Macro level policy such as the NAFTA further supported the commercial orientation of Ontario’s LTC sector. Finally, complex regulatory, reporting and management tools enacted to ensure minimum quality standards have consolidated homes and opened up a new commercial arena in the form of management. With services located in private for-profit and non-profit organizations, state based demands for greater efficiency, for quantitative accountability, and for lean production techniques have increased demands on provider organizations that are funded with public money.lxiii The health sector has adopted numerous NPM tools and approaches. Starting in the 1980s, governments flirted with and implemented competitive, quasi-markets in health care, often referred to as “internal markets”.lxiv Quantitative tools for measuring accountability have proliferated, including the adoption of the Minimum Data Set assessment tool in long-term care.

Table 6.

Summary of Key Historical Junctures in the Development of LTC in Ontario

| Time Periods and Political/Economic Trends | Provincial Trend | Key Regulations | Ontario Political Party in Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1940s – 1965 Shift to Keynesianism |

|

None | Progressive Conservative (1943 – 1985) |

| 1966–1990 From Keynesianism to neo-liberalism |

|

Ontario Nursing Homes Act (1966) Federal Medical Care Act (1966) Ontario Extended Care Funding (1972) Canada Health Act (1984) Canada – US Free Trade Agreement (1989) |

Progressive Conservative (until 1985) Liberal (1985 – 1990) |

| 1990–2006 Neo- liberalism |

|

The Long-Term Care Act (1973) Long Term Care Statute Law Amendment Act – (Bill 101) (1993) North American Free Trade Agreement (1994) |

New Democratic Party (1990 – 1995) Progressive Conservatives (1995 – 2003) Liberals (2003 – present) |

| 2007 – present Neo- liberalism |

|

Ontario Long-term Care Act, 2007 (passed in 2010) | Liberals (2003 – present) |

The central argument of this paper is that with more onerous reporting requirements and a commercialization logic smaller independent homes (both for-profit, public and non-profit ownership) face closure or outsourcing of their management. The logic has favoured consolidation of ownership and management within large, corporate FPC. Why is this important? In a review of Canadian and American research evidence, Margaret McGregor and Lisa Ronald found that for-profit facilities are “likely to produce inferior outcomes” when compared with public and non-profit alternatives.lxv This finding is similar to other studies that have found quality differences by ownership. However, the underlying assumption in research that accounts for ownership and quality in LTC is that public and non-profits differ with commercial firms in their orientation and approach. The interesting point of tension revealed by this research is that the majority of homes in Ontario are FPC, with an increasing number of beds managed by FPC, even when the facility is owned by a non-profit, charitable or public home. What does it mean to be a non-profit or public home if a for-profit is managing the operations? This question raises important tensions to be addressed by researchers in terms of study design and policy makers in terms of discerning how to measure and implement quality programs that are publicly funded but privately delivered. Indeed, increased public reporting of quality data is an option taken in other jurisdictions such as the United States, but with self-reported data there are limits to data reliability as the differences between the survey data (Tables 1–3) and the Ministry reported data (Tables 4–5) show.

Early on in Ontario most long-term care providers were small, independent for-profits. Over time, for-profit nursing homes began to deliver more medical services considered a substitute for hospital convalescence; contemporaneous public and non-profit organizations delivered custodial LTC largely oriented around social care, food and shelter for poor older adults. Accompanying the growth of the commercial sector were cautionary tales about for-profit delivery,lxvi a growing body of research that questioned the compatibility of profit and care, lxvii, lxviii, lxix, lxx and some within government who preferred either public or non-profit delivery. But because the province was slow to regulate and even slower to participate in service delivery, it supported third party delivery by private for-profit and non-profit organizations and created only limited public municipal options. Over time, non-profits and municipalities began to deliver the same levels of hospital convalescence care as nursing homes did. But, only non-profits and municipalities were regulated to provide custodial care thus maintaining some boundaries between for-profits and non-profits. The hegemony of commercial providers began in the post-war period and continues to the present. Regulation of the LTC sector intensified following criticisms about care standards and coinciding with governments that wanted to “steer and not row”lxxi with the advent of New Public Management. By the 1990s, the province legislated LTC out of the custodial/social care realm. It shifted responsibility away from the Ministry of Community and Social Services and consolidated it within the medical continuum of care in the newly created Ministry of Health and Long-term Care (MOHLTC). The new regulatory regime resemble what Walshe refers to as deterrence regulation that is “…formal, legalistic, punitive and sanction-oriented”lxxii The weight of deterrence oriented legislation has contributed to non-profit and municipal homes’ closure and outsourcing of management. The cautionary tale is thus, if the sector is to remain balanced, states must understand the following: the consequences of their role as either compliance or deterrence oriented regulators; how maintaining public ownership of homes is important; why nonprofit and public delivery produces better quality indicators; and whether there are consequences to the outsourcing of management functions.

Figure 1.

Statistics Canada. Table 107-5501 (accessed: September 24, 2013)

Endnotes

- i.Ontario Nursing Home Association (ONHA) Compassionate Journey 40 years of ONHA. HLR Publishing Group; 1999. p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- ii.Armstrong P, Armstrong H, Coburn D. The Political Economy of Health and Care. In: Armstrong P, Armstrong H, Coburn D, editors. Unhealthy Times: Political Economy Perspectives on Health and Care in Canada. Don Mills: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. vii–x. [Google Scholar]

- iii.Pierson P, Skocpol T. Historical Institutionalism in Contemporary Political Science. Paper presented at the American Political Science Association Meetings; Washington D.C. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- iv.Hall PA. The Movement from Keynesianism to Monetarism: Institutional Analysis and British Economic Policy in the 1970s. In: Steinmo S, Thalen K, Longstreth F, editors. Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 90–113. [Google Scholar]

- v.Tuohy C. Accidental Logics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- vi. [accessed February – March 2013];The Ministry of Health and Long-term Care online database called “Reports on Long-Term Care Homes. http://publicreporting.ltchomes.net/en-ca/default.aspx.

- vii.For reviews of staffing intensity see: Bryan S, Murphy J, Doyle-Waters M, Kuramoto L, Ayas N, Maumbusch J, et al. A Systematic Review of Research Evidence on: (a) 24-hour Registered Nurse Availability in Long-term Care, and (b) the Relationship between Nurse Staffing and Quality in Long-term Care 2010Harrington C, Choiniere J, Goldmann M, Jacobsen F, Lloyd L, McGregor MJ, et al. Nursing home staffing standards and staffing levels in six countries. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2012;44(1):88–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01430.x.

- viii.McGregor MJ, Tate RB, Ronald LA, McGrail KM, Cox MB, Berta W, et al. Trends in long-term care staffing by facility ownership in British Columbia, 1996 to 2006. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ix.Berta W, Laporte A, Zarnett D, Valdmanis V, Anderson G. A pan Canadian Perspective on Institutional Long-term Care. Health Policy. 2006;79:175–194. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- x.Berta W, Laporte A, Valdmanis VG. Observations on Institutional Long-Term Care in Ontario: 1996–2002. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2005;24(1):71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xi.McGregor MJ, Cohen M, McGrail K, Broemeling AM, Adler RN, Schulzer M, et al. Staffing Levels in Not-For-Profit and For-Profit Long-Term Care Facilities: Does Type of Ownership Matter? CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2005;172(5):645–649. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xii.McGregor MJ, Tate R, McGrail K, Ronald L, Broemeling AM, Cohen M. Care Outcomes in Long-Term Care Facilities in British Columbia, Canada - Does Ownership Matter? Medical Care. 2006;44(10):929–935. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223477.98594.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xiii.Davis MA. On nursing home quality: a review and analysis. Medical Care Research and Review. 1991;48:129–168. doi: 10.1177/002570879104800202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xiv.Hillmer MP. Nursing Home Profit Status and Quality of Care: Is There Any Evidence of an Association? Medical Care Research and Review. 2005;62(2):139–166. doi: 10.1177/1077558704273769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xv.Comondore VR, Devereaux PJ, Zhou Q, Stone SB, Busse JW, Ravindran NC, et al. Quality of care in for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2732–b2732. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xvi.Kaffenberger KR. Nursing Home Ownership. Journal of Aging & Social Policy. 2001;12(1):35–48. doi: 10.1300/J031v12n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xvii.Harrington C, Hauser C, Olney B, Rosenau PV. Ownership, Financing, and Management Strategies of the Ten Largest For-Profit Nursing Home Chains in the United States. International Journal of Health Services. 2011;41(4):725–746. doi: 10.2190/HS.41.4.g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xviii.Scourfield P. Caretelization revisited and the lessons of Southern Cross. Critical Social Policy. 2012;32(1):137–148. doi: 10.1177/0261018311425202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- xix.Scourfield P. Are there reasons to be worried about the “caretelization” of residential care? Critical Social Policy. 2007;27(2):155–180. doi: 10.1177/0261018306075707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- xx.Amirkhanyan A. Privatizing public nursing homes: examining the effects on quality and access. Public Administration review. 2008;(July/August):665–680. [Google Scholar]

- xxi.Stevenson DG, Bramson JS, Grabowski DC. Nursing Home Ownership Trends and Their Impacts on Quality of Care: A Study Using Detailed Ownership Data From Texas. Journal of Aging & Social Policy. 2013;25(1):30–47. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2012.705702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxii.Walshe K. Regulating U.S. Nursing Homes: Are We Learning From Experience. Health Affairs. 2001;20(6):128–144. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxiii.Walshe K. Regulating. :134. [Google Scholar]

- xxiv.Walshe K. Regulating. :134. [Google Scholar]

- xxv.Statistics Canada defines residential care facilities as “all residential facilities in Canada with four or more beds providing counseling, custodial, supervisory, personal, basic nursing and/or full nursing care to at least one resident. Excluded are those facilities providing active medical treatment (general and allied special hospitals)”. It defines “homes for the aged” as “…nursing homes, homes for the aged and other facilities providing services and care for the aged. Not included are homes for senior citizens or lodges where no care is provided.”

- xxvi.Struthers J. Reluctant Partners: State Regulation of Private Nursing Homes in Ontario, 1941–1972. In: Blake RB, Bryden PE, Strain JF, editors. The Welfare State in Canada: Past, Present, and Future. Concord: Irwin Publishing; 1997. pp. 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- xxvii.Struthers J. Reluctant Partners. :174. [Google Scholar]

- xxviii.Struthers J. Reluctant Partners. 1997:175. [Google Scholar]

- xxix.Struthers J. Reluctant Partners. :177. [Google Scholar]

- xxx.ONHA. Compassionate Journey [Google Scholar]

- xxxi.Struthers J. Reluctant Partners. :180. [Google Scholar]

- xxxii.ONHA. Compassionate Journey. :113. [Google Scholar]

- xxxiii.Struthers J. Reluctant Partners. :180. [Google Scholar]

- xxxiv.Struthers J. Reluctant Partners. :173. [Google Scholar]

- xxxv.Struthers J. Reluctant Partners. :182. [Google Scholar]

- xxxvi.Struthers J. Reluctant Partners. :181. [Google Scholar]

- xxxvii.Tarman VI. Privatization and health care: The Case of Ontario Nursing Homes. Garamond Press; Toronto: 1990. pp. 41–42.pp. 41 [Google Scholar]

- xxxviii.ONHA. Compassionate Journey. :114. [Google Scholar]

- xxxix.Struthers Reluctant Partners. :186. [Google Scholar]

- xl.ONHA. Compassionate Journey. :123. [Google Scholar]

- xli.Tarman VI. Privatization and health care. :45. [Google Scholar]

- xlii.Tarman VI. Privatization and health care. :41. [Google Scholar]

- xliii.ONHA. Compassionate Journey. :122. [Google Scholar]

- xliv.Forbes W, Jackson J, Kraus A. Institutionalization of the Elderly in Canada. Toronto: Butterworths; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- xlv.Tarman VI. Privatization. :42. [Google Scholar]

- xlvi.Chambers L, Labelle R, Gafni A, Goree R. CHEPA Working Paper Series. McMaster University; Hamilton: Apr, 1992. The Organization and Financing of Public and Private Sector Long Term Care Facilities for the Elderly in Canada; pp. 92–8. [Google Scholar]

- xlvii.ONHA. Compassionate Journey. :122. [Google Scholar]

- xlviii.ONHA. Compassionate Journey. :122. as quoted from a 1986 ONHA annual report.

- xlix.ONHA. Compassionate Journey. :124–25. [Google Scholar]

- l.McKay P. Ontario’s Nursing Home Crisis Part 4 Taypayers Finance Construction Boom. The Ottawa Citizen. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- li.Personal communications. Sep, 2013.

- lii.Ministry of Health and Long-term Care. [accessed on Sept 5th, 2013];Seniors’ Care: Home, Community and Residential Care Services for Seniors Important Changes to LTC Home Compliance. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/ltc/trans_project.aspx.

- liii.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care. [accessed on October 10, 2013];Ontario Enhancing Care and Services for Long-Term Care Home Residents. http://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2013/06/ontario-enhancing-care-and-services-for-long-term-care-home-residents.html.

- liv.Armstrong P, Daly T. There are not enough hands’ Conditions in Ontario’s Long Term Care Facilities. Toronto: CUPE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- lv.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care, Ontario. Enhancing Care [Google Scholar]

- lvi.Sharkey S. [accessed on August 25th, 2013];People Caring for People Impacting the Quality of Life and Care of Residents in Long-term Care Homes. 2008 May; http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/staff_care_standards/staff_care_standards.aspx.

- lvii.Schnelle JF, Simmons SF, Harrington C, Cadogan M, Garcia E, Bates-Jensen BM. Relationship of Nursing Home Staffing to Quality of Care. HSR: Health Services Research. 2004 Apr;39(2):225–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lviii.Harrington C, Kovner C, Mezey M, Kayser-Jones J, Burger S, Mohler M, et al. Experts Recommend Minimum Nurse Staffing Standards for Nursing Facilities in the United States. The Gerontologist. 2000;40(7):5–76. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lix.Leisureworld. Annual report. 2010:7. [Google Scholar]

- lx.Tarman VI. :41–42. [Google Scholar]

- lxi.Scourfield. Caretelization revisited. :137–148. [Google Scholar]

- lxii.Harrington C, Hauser C, Olney B, Vaillancourt-Rosenau P. Ownership, Financing, and Management Strategies of the Ten Largest For-Profit Nursing Home Chains in the United States. International Journal of Health Services. 2011;41(4):725–746. doi: 10.2190/HS.41.4.g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lxiii.Charlesworth S. The Regulation of Paid Care Workers’ Wages and Conditions in the Non-Profit Sector: A Toronto Case Study. Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations. 2010;65(3):380. [Google Scholar]

- lxiv.Ham C. Learning from the NHS Internal Market: A Review of the Evidence. Kings Fund; 1999. p. 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lxv.McGregor M, Ronald L. Residential Long-Term Care for Seniors: Nonprofit, For-profit or Does it Matter? IRPP study. 2011 Jan;(14):1. [Google Scholar]

- lxvi.Struthers J. Reluctant Partners. :173–180. [Google Scholar]

- lxvii.Struthers J. Reluctant Partners. :173–180. [Google Scholar]

- lxviii.Fottler MDM, Smith HLH, James WLW. Profits and patient care quality in nursing homes: are they compatible? The Gerontologist. 1981;21(5):532–538. doi: 10.1093/geront/21.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lxix.Elwell F. The effects of ownership on institutional services. The Gerontologist. 1984;24(1):77–83. doi: 10.1093/geront/24.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lxx.Lemke S, Moos RH. Ownership and quality of care in residential facilities for the elderly. The Gerontologist. 1989;29(2):209–215. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- lxxi.Osbourne D, Gaebler T. Reinventing Government. Addison-Wesley Publ. Co; 1992. p. 427. [Google Scholar]

- lxxii.Walshe K. Regulating. 2001:133. [Google Scholar]