Abstract

Sphingolipids are both, fundamental structural components of the eukaryotic membranes and signaling molecules regulating a variety of biological functions. Highly bioactive lipids, ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate have emerged as important regulators of cardiovascular functions in health and disease. In this review we discuss recent insights into the role of sphingolipids, particularly ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate, in the pathophysiology of the cardiovascular system. We also highlight advances into the molecular mechanisms regulating serine palmitoyltransferase, the first and rate-limiting enzyme of de novo biosynthesis, with an emphasis on recently discovered inhibitors of serine palmitoyltransferase, ORMDL and NOGO-B proteins. Understanding the molecular mechanisms regulating this biosynthetic pathway may lead to the development of novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Sphingolipids, SPT, Nogo-B, cardiovascular diseases

Regulatory mechanisms of SPT

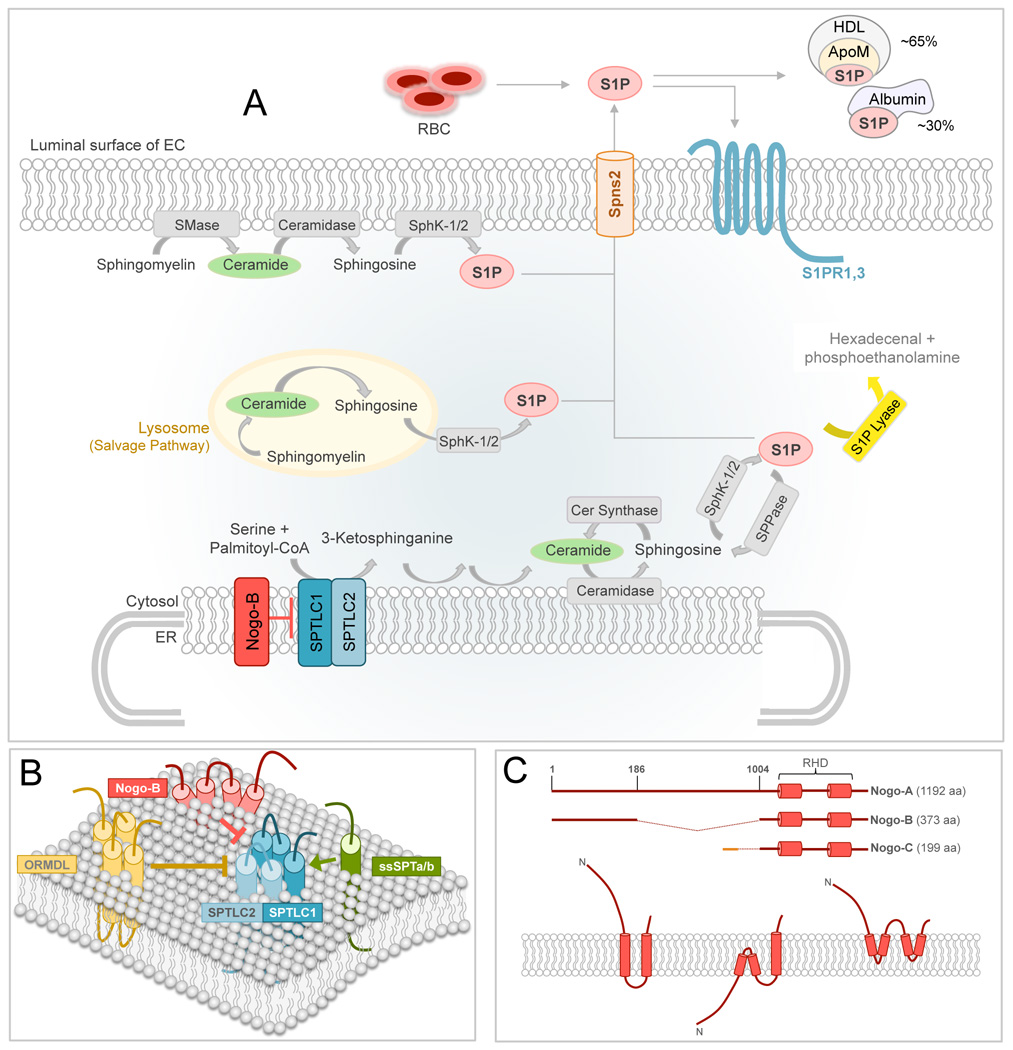

Sphingolipid (SL) de novo biosynthesis occurs in the cytosolic leaflet of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (see Glossary) where serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) catalyzes the first and rate-limiting step, the decarboxylative of palmitoyl-coenzyme A with L-serine to generate 3-ketosphinganine (Figure 1A, B) [1]. The highly conserved SPT enzyme belongs to the oxoamine synthases family and is a membrane-bound heterodimer composed of two subunits, first identified as Lcb1/Lcb2 in yeast [2–4]. In mammals, there is a single Lcb1 homolog, Serine PalmitoylTransferase Long Chain base subunit 1 (SPTLC1), and two homologs of Lcb2, SPTLC2 [5, 6] and SPTLC3 [7]. The SPTLC2 and SPTLC3 subunits of SPT display distinct expression patterns in vivo [7]. Modeling studies using other members of the oxoamine synthases, first AONS [8] and later bacterial SPT [9], suggested that the active site of SPT lies at the heterodimeric interface with each subunit contributing catalytic residues, and this has been confirmed from mutational studies [8, 10, 11]. The topology and the stoichiometry of SPT subunits are still under debate. An initial study by Yasuda et al. proposed Lcb1 as a single transmembrane (TM) protein with an ER luminal N-terminus and a cytosolic C-terminus [12]. Later on, Han et al. demonstrated the presence of three membrane-spanning domains and showed that the first TM domain of both yeast and human LCB1 can be deleted without affecting membrane targeting, formation of the LCB1/LCB2 heterodimer, or enzymatic activity [13].

Figure 1. Sphingolipid biosynthesis and SPT regulation.

(A) In the ER membrane, serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) starts the de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis by condensing serine and palmitoyl-CoA to form 3-ketosphinganine, which is further modified to generate ceramide (Cer). Ceramide can also derive from the catabolism of sphingomyelin (SM) in the plasma membrane or in the lysosome. Ceramidase converts ceramide in sphingosine, which in turn is phosphorylated to sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) by the sphingosine kinase 1 or 2 (SphK-1/2). S1P is then transported out of the cells through the spinster-2 (Spns2) or other transporters, where it can bind to and activate S1PR1,3 in an autocrine manner, or it can bind its plasma carriers, albumin and ApoM of HDL. S1P lyase irreversibly degrades S1P in hexadecanal and phosphoethanolamine, representing the exit point of this pathway.

(B) Schematic representation of SPT complex, including SPTLC1/2, its activators ssSPTa/b and negative regulators ORMDL and NOGO-B. (C) Upper panel, schematic representation of Reticulon-4 (aka NOGO) isoforms. Reticulon homology domain (RHD) defines the two transmembrane (TM) domains and the loop of 66 aa connecting them. Lower panel, three proposed topologies for NOGO proteins.

The stoichiometry of the SPT complex was initially proposed as a heterodimer composed of Lcb1 and Lcb2 in 1:1 ratio [14]. Recently, SPT was suggested to be an octameric complex of four heterodimers resulting from the interaction of SPTLC1 with either SPTLC2 or SPTLC3, depending on the expression pattern of SPT subunits and the cellular sphingolipid requirement [15].

Although SL are recognized as essential membrane components and bioactive signaling molecules [1], little is known about the regulation of their synthesis. Orthologous to the yeast Tsc3 [16], the SPT small subunits a and b (ssSPTa and ssSPTb), are independent activators of mammalian SPT [17]. The interaction of ssSPTa and b with SPT via their single TM domain is sufficient for boosting the activity of the enzyme [18]. Whether or not ssSPTa and b are also regulated at transcriptional or post-translational level is not known.

To date two proteins have been shown to negatively regulate SPT in mammals, the ORosoMucoiD-Like (ORMDL) proteins and Neurite OutGrowth inhibitor (NOGO-B), both conserved transmembrane proteins of the ER. Three different genes encode the ORMDL proteins (ORMDL1-3), which display different patterns of expression in vivo [19]. The yeast orthologous, Orm1 and Orm2 share ca. 35% of homology with the ORMDLs [19]. The role of the Orm proteins in regulation of SPT was first reported in an elegant study by Breslow and colleagues who showed that the Orms inhibit SPT when the cells have sufficient levels of SL [20], and the lack of Orms significantly increased he activity of SPT of six folds. When sphingolipid synthesis is disrupted by myriocin, an inhibitor of SPT activity [21], the Orms are phosphorylated at multiple sites and the inhibitory brake on SPT is relieved. As predicted, deletion or phosphomimicking mutations in the ORMs cause hyperactivation of SPT [20].

Recent studies have begun to delineate the phosphorylation pathway activated by myriocin as well as by heat stress, leading to Orm phosphorylation. Yeast Protein Kinase 1 (Ypk1) phosphorylates the Orms following myriocin treatment [22] or heat stress [23]. Nutrient depletion also stimulates Orm phosphorylation, but with a different pattern and without affecting SPT activity [24], suggesting that the Orms may have additional biological functions apart from the inhibition of SPT activity.

Furthermore, the morphogenesis checkpoint kinase Swe1 has also been linked to Orm phosphorylation. Yeast lacking Swe1 shows decreased levels of SL and increased sensitivity to myriocin-induced growth inhibition, suggesting that Swe plays a role in controlling sphingolipid homeostasis [25].

However, whereas the mechanisms responsible for Orm regulation of yeast SPT are being elucidated, regulation of mammalian SPT by the ORMDLs is poorly understood. The ORMDLs lack the N-terminus containing the phosphorylation sites [19], indicating that different regulatory mechanisms control ORMDL-SPT interactions.

Recently, NOGO-B was identified as a negative regulator of SPT activity in mammals [26]. NOGO-B belongs to the large family of Reticulon (RTN) proteins, so called for their localization in the tubular ER through two transmembrane domains separated by a loop of 66-aa named reticulon-homology domain (RHD, Figure 1C) [27]. Of the four Reticulon genes in mammals, Rtn-4 gives rise to three major isoforms, RTN-4A, −4B and −4C (aka NOGO-A, -B, and -C). The topology of NOGO proteins is still under debate. Three possible orientations in the ER membrane have been proposed [28, 29]. While NOGO-A and NOGO-C are expressed in the central nervous system, with low levels of NOGO-C also in the skeletal muscle, NOGO-B is highly, but not exclusively, expressed in the blood vessels [26].

Voeltz et al. elegantly demonstrated that an important biological function of reticulons is to facilitate the formation of the tubular ER network [27, 29]. For other NOGO-related functions, including inhibition of neuronal outgrowth [30] and stimulation of EC migration [31], putative receptors have been suggested as mediators. Given that more than 95% of NOGO proteins are localized in the tubular ER, with the remaining fraction on the cell membrane, the ligand-receptor model proposed remains controversial.

In addition to shaping the tubular ER, a basic intracellular function of NOGO-B is to interact with and inhibit SPT activity. NOGO-B co-localizes with SPT in the tubular ER and co-immunoprecipitates with SPT and the ORMDLs. In the absence of NOGO-B, SPT activity is significantly upregulated by about 40% and the lentiviral-mediated re-expression of NOGO-B restores the activity of SPT to control levels. The inhibitory function of NOGO-B on SPT has been confirmed in murine and human endothelial cells (EC), mouse lung, and heart microsomal preparations, deplete vs. replete of NOGO-B [26]. It is noteworthy to mention that in absence of endothelial NOGO-B not only sphinganine, but also ceramide (C18-, C20- and C22-ceramide), sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) are significantly increased. Myriocin treatment markedly reduces S1P production (~50%) suggesting an important contribution of the de novo pathway to the endothelial-derived S1P. However, the most abundant ceramides (C16-, C24-, and C26-cermide) were unchanged. Whether the lack of NOGO-B affects other metabolic steps of the de novo pathway, and/or ceramide synthase activity is unknown and further studies are needed to clarify the molecular mechanism/s accountable for that specific changes in SL profile.

Although SPT is fundamental during development [32], the regulatory mechanisms of this enzyme remain poorly understood. Specific molecular interactions of ORMDLs and NOGO-B with SPT complex and their mechanisms of regulation have yet to be identified. Furthermore, how the SPT complex can sense changes in sphingolipid levels and maintain cellular sphingolipid homeostasis is not understood. Are there cell-specific regulatory mechanisms of SPT in mammals since the ORMDLs and NOGO-B present a specific distribution pattern? Are there other regulatory members of the SPT complex still to be discovered? Lastly, how is SPT regulated in pathological conditions? In exploring strategies for modulating the sphingolipid de novo pathway it is imperative to understand regulation, particularly of the rate-limiting step, and the downstream effects of their inhibition, especially considering all the side branches of this pathway.

Locally produced S1P and ceramide in vascular tone regulation

Endothelial S1P-S1P receptor 1 (S1P-S1PR1) signaling: regulator of vascular barrier, tone and flow

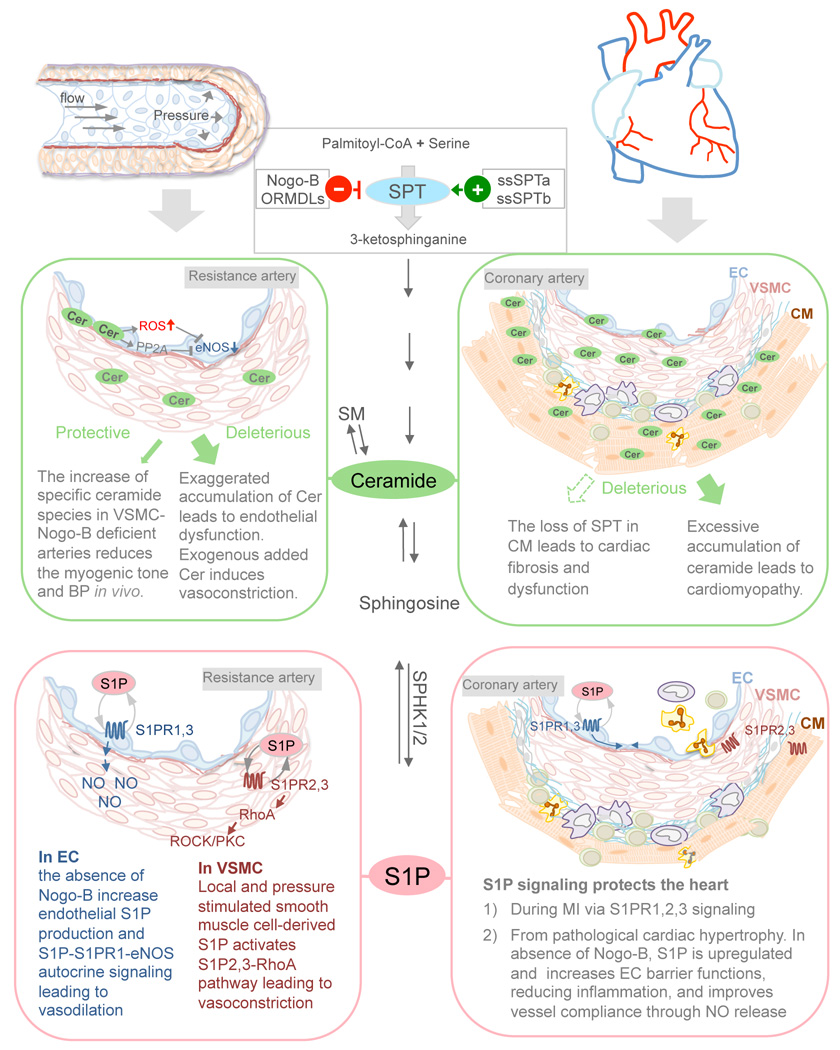

Ceramide represents a nodal point of the sphingolipid de novo pathway (Figure 1): it can be reversibly converted to higher order SL, including sphingomyelin (SM) and glycosphingolipids; it can be degraded to sphingosine, or a small fraction can be phosphorylated to form ceramide-1-phosphate [1]. Two sphingosine kinases (SPHK1 and SPHK2) phosphorylate sphingosine to generate S1P, which is rapidly secreted outside of the cells, where it can bind to and activate five G-protein coupled receptors, named S1PR1-S1PR5 [33]. In physiological conditions, erythrocytes [34] and EC [35, 36] are major sources of plasma S1P. Reaching concentrations of 0.1–1 nM, plasma S1P is bound to apolipoprotein M (ApoM) of HLD (ca. 60%) and albumin (ca. 35%) [37, 38]. Whether or not these carriers also control the “availability” of S1P to S1PRs is still unclear. In the cardiovascular system, different levels of S1PR1, S1PR2 and S1PR3 are expressed in various cell types. In the EC, S1PR1 is the most abundant receptor [39] (S1PR1 16-fold higher than S1PR3) and regulates vascular development, angiogenesis, endothelial barrier integrity [40] and vascular tone [41].

Low levels of plasma S1P, such as in the absence of SPHK [42] and ApoM [37], and the lack of endothelial S1PR1 [43] cause the disruption of the S1P-S1PR signaling leading to a general increase in vascular permeability. Interestingly, in humans [44] and baboons [45] the severity of sepsis inversely correlates with plasma levels of ApoM. Altogether, these findings suggest the importance of S1P signaling in vascular homeostasis.

The endothelium actively controls vascular tone and blood pressure (BP). Following chemical and mechanical stimuli, including changes in shear stress, the endothelium releases different vasoactive factors, including prostacyclin, endothelin, nitric oxide (NO) [46], and S1P [35]. Changes in flow induce endothelial synthesis of S1P [35], which in turn is transported outside of the EC through specific spinster-2 transporter [47] to stimulate S1PR1 in an autocrine manner [48] and downstream eNOS [49], of a magnitude comparable to acetylcholine and bradykinin.

Multiple evidences have suggested an important role of S1PR1 in the endothelial response to flow. In absence of S1PR1, changes in flow fail to induce EC alignment and eNOS phosphorylation, in vivo as well as in vitro [50]. Furthermore, the inhibition of S1PR1 with W146 reduces the vasodilation to flow and the NO production [26], suggesting that S1PR1 is an active player of the mechanotransduction signaling pathway controlling blood flow. A recent study from Galvani and colleagues, by using different genetic mouse models, demonstrated anti-inflammatory and anti-atherosclerotic functions of the S1PR1 signaling, particularly in vascular points exposed to turbulent flow such as the lesser curvature and branch points in vivo, more susceptible to the development of atherosclerotic lesions [51].

A critical role of NOGO-B in controlling endothelial-derived S1P to impact BP through the S1PR1-eNOS autocrine axis was recently demonstrated. Sphingolipid de novo biosynthesis is an important, although not exclusive, determinant of endothelial produced S1P and genetic or pharmacological modulation of the de novo pathway within the vasculature markedly impacts BP homeostasis. In mice lacking Nogo-B, the endothelium produces higher levels of S1P conferring resistance to endothelial dysfunction and hypertension [26]. Remarkably, the activation of S1PR1 with SEW2871 markedly lowers BP in hypertensive mice. On the contrary, pharmacological inhibition of SPT with myriocin restores BP in mice lacking NOGO to WT levels [26], suggesting that 1) locally produced de novo SL, within the vascular wall, are necessary to control vascular functions, despite the high levels of SL in the plasma, and 2) S1PR1 signaling is a novel anti-hypertensive pathway.

The importance of locally produced S1P in vascular tone regulation was further corroborated by other studies. Following carbachol stimulation, a muscarinic M3 receptor agonist, SPHK1 rapidly translocate to the plasma membrane, implicating the contribution of endothelial S1P in the vasodilation induced by muscarinic agonists [52, 53].

Altogether, these findings underline previously underappreciated roles of sphingolipid biosynthesis and signaling in BP homeostasis and provide a framework for investigating whether alterations of NOGO-mediated regulation of sphingolipid metabolism and signals contribute to other cardiovascular diseases, or other pathological conditions linked to the alteration of this pathway.

Vascular produced S1P and myogenic tone

In vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC), S1P activates S1PR2 and S1PR3 to induce vasoconstriction of the media layer mediated by Ca++/Rho pathway in rodents[41], porcine [54] and human arteries [55, 56].

While endothelial S1P activates the S1PR1-eNOS autocrine signaling, other studies suggested that S1P produced in the vascular wall also participate to the myogenic tone. Changes in pressure trigger S1P production in rabbit posterior cerebral arteries [57]. Furthermore, elevated levels of S1P in the vascular wall through Sphk1 overexpression [58] or S1P-phosphohydrolase knockdown [59] increase the myogenic tone of resistance arteries, whereas the overexpression of S1P-phosphohydrolase decreases vascular tone in response to pressure, implicating local produced S1P in myogenic tone regulation. Recently, Hoefer et al. demonstrated that during heart failure the myogenic tone of resistance arteries increases, and the hyperactivation of S1P-S1PR2 autocrine axis is accountable for it [60]. Whether or not the increase in the myogenic tone is due exclusively to an increase of S1P-S1PR2 autocrine loop in the VSMC or also to the disruption of the vasoprotective S1P-S1PR1 signaling in the endothelium, remains an open question.

Clearly S1PRs can be modulated in vivo by locally produced S1P. Understanding how S1P autocrine loops in the EC and VSMC change during cardiovascular disease, including hypertension and heart failure, would definitely contribute to our understanding of this pathway in cardiovascular homeostasis but also provide possible pharmacological targets, from the biosynthesis of S1P to its downstream receptors.

Ceramide and vascular tone regulation

The accrual of circulating and local ceramide in certain pathological conditions, including obesity and type-2 diabetes, has been linked to detrimental vascular effects and endothelial dysfunction discussed hereafter. Both glucose and palmitate trigger the de novo biosynthesis of ceramide, which interferes with eNOS-derived NO production through the activation of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) [61–64] and impact BP [62, 64]. Ceramide also promotes NADPH oxidase activity and ROS formation at the expense of endothelial NO [65]. A recent study from Freed et al. demonstrated that long treatment ex-vivo of human resistance arterioles with ceramide triggers the formation of mitochondrial-derived H2O2, counteracting the NO which is associated with an inflammatory and dysfunctional state of the endothelium. Interestingly, the inhibition of neutral sphingomyelinase (nSMase) restores the physiological phenotype in arterioles from patients affected by coronary artery disease [66]. In another study, Spijkers L.J. et al. showed an increase of ceramide, but not SM, in the plasma of hypertensive rats and patients. They proposed that endothelial-derived thromboxane A2 was accountable for the hypercontractility of rat carotid arteries induced by ceramide [67]. Altogether these studies support the concept that ceramide accrual is “deleterious” for the endothelial functions.

On the other hand, few studies also reported that acute administration of ceramide induces eNOS-dependent vasorelaxation [68]. It is of noteworthy to mention that C6-ceramide coated catheters limit neointimal hyperplasia while promoting the re-endothelialization of injured arteries [69], suggesting cell-type and pathological state-dependent functions.

Another line of investigation demonstrates a role of ceramide in VSMC contraction. SMase and some ceramide species induce a sustained vasoconstriction of cerebral arteries and venules in rats and dogs [70, 71]. Although preliminary, these studies suggest that ceramide plays an important role in the pathogenesis of hypertension. To date, the paradigms to study ceramide functions in vascular tone regulation mainly involved the administration of exogenous ceramide or nSMase. Genetic mouse models such as dihydroceramide desaturase 1 heterozygous (Des1+/−) has been used to study the role of ceramide in the vasculature in models of diet-induced obesity and type-2-diabetes[62, 64]. The next step would be to manipulate the biosynthetic pathway with potential to result in endogenous changes in ceramide levels, possibly in specific cell types (EC vs. VSMC), to recapitulate more closely pathological conditions such as hypertension.

The role of ceramide in myogenic tone has been poorly investigated. It was recently reported that the lack of Nogo-B in VSMC leads to a selective increase of ceramide species (C18-cer, C20-cer, C22-cer) with specific reduction only in the myogenic tone, leading to a lower BP, suggesting a distinct involvement of ceramide in pressure-induced vasoconstriction [26]. Of course, as central metabolite of an highly dynamic metabolic pathway, we need to keep in mind that ceramide can give rise to other SL, including sphingosine and S1P that could also account for the biological functions associated to ceramide. Furthermore, whether or not the sources of ceramide (de novo vs. SMase) can generate a specific subset of ceramide species, and/or lead to a preferential accumulation in distinct subcellular compartments linked to finite biological functions is unknown. Finally, the identity of the vessels (arteries vs. veins; capacitance vs. resistance arteries), their pathophysiological state, the methods used to evaluate vascular functions, the correlation of vascular function with NO levels, and the amount of ceramides also need to be taken into account when considering the net effect of ceramide on vascular tone.

Sphingolipid de novo pathway and S1P in the heart

Based on the current literature, whether changes in plasma levels of S1P may have causative or consequential effects during ischemic heart diseases remain unclear. Clinical studies have demonstrated that following myocardial infarction (MI) plasma levels of S1P decrease in the first days [72], and remain low up to two years [73]. A recent study of Sutter et al further confirmed these findings in acute MI patients [74]. Conversely, other studies reported increased[75] or unchanged [76] plasma levels of S1P in patients post-MI. Different reasons could explain these controversies, including when the blood samples were taken (i.e. before, after or during stent implantation), the methodologies employed to quantify S1P, whether or not S1P was normalized to plasma HDL, and lastly the medication given to the patients. Reduced levels of plasma S1P have been also reported in patients affected by coronary artery diseases and they inversely correlate with the severity of the diseases[77, 78]. In spite of discordant changes in plasma S1P following MI in preclinical studies[73, 79, 80], administration of HDL and S1P to the mice protected the heart from ischemia reperfusion injury [81], underlining a cardioprotective function of S1P signaling.

S1P protects cardiomyocyte (CM) from hypoxia-induced damage in vitro, as well as from ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury inflicted to the heart ex-vivo in a Langendorff perfusion system (comprehensively reviewed elsewhere [82, 83]). By using systemic knockout mouse models, Means and colleagues elegantly demonstrate an important and redundant cardioprotective role of S1PR2 and S1PR3 from I/R injury [84] in vivo by using global knockout mouse models, although a direct role of these receptors on CM biology was not demonstrated. S1PR3 was also shown to mediate HDL-induced protection of the heart from I/R damage[81]. It is still unclear which S1P receptor/s on CM is accountable for the S1P protection from insults.

Pharmacological approaches suggest that S1PR1 mediates the protective actions of S1P on CM in vitro [85]. S1PR1 cardiac gene therapy in vivo protects the heart from ischemic injury[86]. However, data on the S1PR1 expression in CM are discordant. Although CM seem to express S1PR1 mRNA [85], an elegant study from Chae et al. using a β-galactosidase reporter knockin mouse model demonstrated that S1PR1 is mainly expressed in EC and in CM of the atria but undetectable in the ventricle [87], corroborated also by Forrest et al. [88]. Interestingly, a very recent study by Keul et al. demonstrated that the excision of S1PR1 in CM by using α-myosin heavy chain promoter (α-MHC-Cre) strategy did not affect myocardial infarction compared to WT mice[89], suggesting that S1PR1 does not play a main role in this pathological scenario. Data on CM in vitro showed that S1PR1 plays an important role in intracellular Ca++ homeostasis through its inhibitory effect on adenylate cyclase, while the loss of S1PR1 in CM led to age-dependent dilated cardiomyopathy and spontaneous death of the mice[89]. It is noteworthy to mention that α-MHC-Cre mice manifest a Cre- and age-dependent cardiotoxicity [90] warranting caution in the interpretation of these data. Administration of SEW2871, a S1PR1 agonist, preserves the heart from MI damage [91], suggesting that in addition to CM, S1PR1 in the endothelial cells might also contribute to the cardioprotective functions imputable to S1PR1.

Other functions of S1P signaling in the heart, including chronotropic and inotropic effects, have been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere[83, 92]. To date only few studies in vitro suggested a pro-hypertrophic function for S1P on CM through S1PR1 [93, 94], while the role of S1P signaling in pathological cardiac hypertrophy (PCH) induced by pressure overload is virtually unexplored. A recent study from Zhang et al. demonstrated that endothelial S1P protects the heart from inflammation, fibrosis and loss of function during chronic pressure overload through the activation of the endothelial S1P-S1PR1-eNOS autocrine signaling[95]. In the heart Nogo-B, identified as inhibitor of SPT (Figure 1), is expressed only in blood vessels and atria but not in ventricular CM. In mice lacking NOGO-B the endothelium produces higher levels of S1P, which activates S1PR1, 3, on the EC surface inducing NO production and endothelial barrier integrity (Figure 2), thus improving vessel compliance to the high pressure and reducing extravasation of plasma proteins and inflammatory cells. Considering the vicinity of capillaries and myocytes, vascular-derived SL, particularly S1P, could also directly impact CM biology. Interestingly, SEW2871 protect the heart from PCH triggered by chronic pressure overload, supporting a cardioprotective role of S1PR1 signaling [95].

Figure 2. S1P, ceramide and their de novo biosynthesis in the cardiovascular pathophysiology.

Schematic summary of the roles of ceramide, S1P and Nogo-B-dependent inhibition of SPT in the regulation of vascular tone and BP (left panels) and in cardiomyopathies (right panels).

In the cardiomyopathies associated to metabolic diseases, the upregulation of the de novo pathway and the accumulation of SL, particularly ceramide, have been considered deleterious for the heart (comprehensively reviewed elsewhere [96–98]). However, systemic loss of SPT is genetically lethal [32], while CM-specific deficiency of SPT leads to cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction, despite the reduction in ceramide [99]. In agreement with these findings, the inhibition of SPT by myriocin restores the PCH in Nogo-A/B-deficient mice following pressure overload[95], supporting a cardioprotective role of SPT. Apparently contradictory, these lines of evidence suggest that 1) SL are necessary to maintain cardiovascular homeostasis; 2) SL levels need to be contained in a rather finite physiological window; 3) SL de novo biosynthesis has to be tightly regulated because an exaggerated production of SL, such as during metabolic diseases, triggers derangement of cardiovascular functions.

The molecular mechanisms regulating the transition from physiological cardiac hypertrophy to PCH remain unclear. Sphingolipid de novo biosynthesis and Nogo-B-mediated inhibition of SPT play an important role in the onset of PCH and open new questions. In the heart, Nogo-B is expressed constitutively also in VSMC and transiently in some CM (ca. 20%) following pressure overload. How does Nogo-B-mediated inhibition of SPT in these cell types affect the onset of PCH? Does SPT activity and SL levels change during the pathogenesis of heart failure? And how? Which S1P receptor/s mediate the cardioprotective functions of S1P? Does the expression of S1P receptors change in PCH? CM-specific knockout mice for the players of this pathway could answer important questions in this field and facilitate possible pharmacological treatment of this condition.

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

A growing body of literature suggests that dysregulation of sphingolipid metabolism and signaling may have a causative role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. ORMDLs and Nogo-B are negative regulators of SPT, the enzyme controlling the rate-limiting step of the SL production. However, the regulatory mechanisms of sphingolipid biosynthesis, and particularly of SPT, in health and diseases are not well understood (see Outstanding Questions).

Outstanding Questions Box.

How is SPT regulated in mammalian cells? ORMDLs and Nogo-B have been identified as negative regulator but the molecular mechanisms relieving their inhibitory actions on SPT are unknown. ORMDLs and Nogo-B seem to have a different expression pattern in vivo. Are there any cell-specific regulatory mechanisms for SPT? What is the expression pattern of these inhibitory molecules in vivo in pathophysiological conditions? Are there other regulatory subunits of the SPT complex still to be discovered?

Nogo-B inhibition on SPT plays a key role in maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis, mainly through the regulation of the endothelial S1P-S1PR1-eNOS autocrine signaling. However, specific ceramide species are also upregulated in both EC and VSMC. What is the biological function of these SL in the blood vessels? Despite the increase in ceramide levels, the endothelial function was preserved as well as NO production. Is it possible that the rheostat S1P/ceramide dictates the pathophysiological state of the vessels? Are different pools of ceramide (de novo vs. SMase) exerting distinct intracellular functions?

S1PR-mediate signaling exerts cardioprotective functions from MI and PCH, and patients affected by MI have lower plasma levels of S1P. What is the biological role of this change? Is the decrease of plasma S1P due to an impaired S1P production/release or to an increased degradation? And in which cell type/s the synthesis/release of S1P is reduced?

In absence of Nogo-B, the upregulation of SPT in EC protects the mice from PCH via S1P-S1P1-eNOS signaling axis. Is Nogo-B expressed in VSMC of the coronary vasculature playing a role during chronic pressure overload? Is Nogo-B expressed in a small fraction of CM following pressure overload playing any role in PCH?

Excessive accumulation and decrease of ceramide are both deleterious for the heart, suggesting that sphingolipid production must be tightly controlled. What is the role of SPT and how its activity is regulated during the pathogenesis of hypertension or heart failure remain unknown.

The upregulation of sphingolipid production, particularly of S1P, and S1P signaling exert protective functions in hypertension [26], PCH [95], atherosclerosis [51] and vascular barrier maintenance [37, 42, 43, 95] mainly though the receptor S1PR1.

Diversely, in others pathological states, such as metabolic diseases, the exaggerated accumulation of SL, particularly of ceramide, has deleterious effects on the cardiovascular system [61–67], suggesting that local SL levels need to be maintained within a limited physiological window. These findings also suggest that relative abundance of SL species (for instance S1P vs. ceramide) may determine the net biological effects, although further studies are needed to confirm the concept of S1P/ceramide rheostat in CV diseases. The concept of S1P/ceramide rheostat in cell fate and cancer has been recently discussed elsewhere[100].

Studies enhancing our understanding of the regulation and functions of SL de novo pathway during the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension and cardiomyopathy, are strongly warranted to provide a framework for therapeutic modulation of this pathway.

Lastly, in the developments of agents targeting the bioactive SL and its signaling pathways, particularly the SPHKs/S1P/S1PR1, potential cardiovascular effects should be a consideration.

Box 1: Overview of SLs.

SLs are a class of lipids characterized by an eighteen-carbon amino-alcohol backbone, also defined sphingoid base, and are synthesized de novo from serine and a fatty acyl-coenzyme A by the enzyme serine palmitoyltransferase. Discovered in brain extracts in 1870s, sphingosine (from “Sphinx”) owes its name to J.L.W. Thudichum “in commemoration of the many enigmas which it presents to the inquirer”. Phosphorylation, acylation and glycosylation of the simplest sphingoid bases, such as sphingosine, phytosphingosine, and dihydrosphingosine, give rise to the variety of complex SLs.

De novo sphingolipid biosynthesis starts in the smooth ER where ceramide is produced (Figure 1), and is completed in the Golgi where the most complex SLs are synthesized, including sphingomyelins (SM) and glycosphingolipids (GSL). The phosphorylation of these sphingoid bases forms the respective −1-phosphate SLs, among which sphingosine-1-phosphate, highly bioactive lipid, is the most studied. The acylation (the addition of a fatty acid chain of length usually between 14 and 26 carbon atoms) of the sphingoid bases sphingosine, dihydrosphingosine and phytosphingosine produces ceramide, dihydroceramide and phytoceramide respectively. Since ceramides are hydrophobic molecules they need a carrier to be moved from the ER to the Golgi, this transport is performed both by vesicles and by the protein CERT. Addition of phosphocholin or, to a small extent, phosphoethanolamine to ceramides forms SM, the major phosphosphingolipids of mammals. Glycosylation of ceramides with one or more sugar residues produces the class of GSL, comprising many members that differ in the number and type of sugar residues attached. Breakdown of complex SLs to ceramide and then to sphingoid bases is called “salvage pathway” and starts in the lysosome. Essential structural membrane component, some of them are also bioactive lipids acting as signaling and regulatory molecules. They are involved in many cellular processes such as cell-stress responses, cell survival, differentiation, cell migration, inflammation, etc. As a consequence, conditions altering this pathway have an impact on many human diseases.

Box 2: Ceramide in Cardiac Hypertrophy.

Multiple lines of evidence suggested a deleterious role of ceramide accrual in the cardiomyocytes in vitro[1, 2] and in vivo in cardiomyopathies associated to systemic metabolic diseases herein and elsewhere discussed[3–6]. Upregulation of the de novo SL production was accountable for this metabolic derangement. Genetic manipulations of lipid pathways could recapitulate the myocardial lipotoxicity during metabolic syndromes. Cardiac overexpression of a membrane-anchored lipoprotein lipase increased the uptake of fatty acids (FA) and the accumulation of triglycerides and ceramide in cardiomyocytes, leading to cardiac dysfunction[7]. Interestingly, the inhibition sphingolipid de novo biosynthesis with myriocin or the excision of one copy of Sptlc1 restored the normal function of the heart[7], and lowered ceramide and sphingomyelin, but not diacylglycerol levels, suggesting a causative correlation between the accumulation of ceramide and the cardiomyopathies[8]. Recently, Russo and colleagues reported that in addition to palmitoyl-derived SL, fatty acid overload leads to a conspicuous myocardial accumulation of myristate-derived SL, attributed to the SPTLC3 subunit of SPT and involved in CM apoptosis but not autophagy. Furthermore, the inhibition of SPT with myriocin protected the mice from lipotoxic cardiac hypertrophy[9]. Altogether, these findings are well supported by clinical data showing a direct correlation between plasma ceramide levels and the severity of symptoms and mortality of patients with chronic heart failure[10].

Recently, two independent groups demonstrated that mice challenged with long-term high fat diet accumulate ceramide into the heart and develop to cardiac hypertrophy[11, 12]. Interestingly, the inhibition of the activity[12] or the expression[11] of AMPK re-established a normal metabolic state, and reduced myocardial accumulation of ceramide, suggesting AMPK as an important player in the lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. Nevertheless, other studies have also shown that ceramide levels were not altered in the heart of mice fed with high fat diet[13] as well as in patients with Obesity/type 2 diabetes mellitus[14]. The discordance in these reports might lie in the different approaches employed to measure ceramides, such as immunostaining in the former and mass spectrometry in the latter. However, a recent study from Chokshi et al. elegantly showed that mechanical unloading of the failing heart is sufficient to correct the metabolic derangement in patients[15], suggesting a link between hemodynamic stress and lipid metabolism homeostasis.

Whereas an exaggerated accumulation of SL in the heart is regarded as deleterious, recent lines of investigation have evidenced the requirement of SL to preserve cardiac homeostasis. The genetic deletion of Sptlc2 gene specifically in cardiomyocytes promotes cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction despite the reduction in ceramide levels[16]. In agreement with these findings, recently Zhang et al. showed that mice lacking Nogo-B, inhibitor of SPT, preserve cardiac function following pressure overload, whereas the inhibition of SPT with myriocin restored pathological cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction to WT levels. This study also demonstrated that endothelial-derived SL, particularly S1P, play a critical role in protecting the heart from failure when challenged with chronic pressure overload[17]. Apparently contradictory, all these lines of evidence suggest that SL levels need to be contained in a rather narrow physiological window; hence the regulation of de novo biosynthesis of SL is of critical importance to maintain cardiovascular homeostasis. The contribution of this metabolic pathway in cardiovascular diseases is only beginning to be elucidated. More studies need to be done to better understand the role and the regulation of SL metabolism in CV physiology and pathology.

TRENDS BOX.

NOGO-B and ORMDLs proteins are negative regulators of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), the first and rate-limiting step of sphingolipid de novo biosynthesis. In blood vessels, Nogo-B-mediated inhibition of SPT plays an important role in the onset of endothelial dysfunction, hypertension and pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

The upregulation of the sphingolipid de novo biosynthesis within a physiological range exerts protective functions, particularly through sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) signaling, whereas the exaggerated upregulation of this pathway leads to accrual of ceramide in plasma and tissues, leading to cardiovascular dysfunctions.

Understanding the molecular mechanisms regulating the inhibitory actions of NOGO-B and ORMDLs on SPT activity may provide the basis for therapeutic modulation of this pathway.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01HL126913-01 and a Harold S. Geneen Charitable Trust Award for Coronary Heart Disease Research to A. Di Lorenzo.

Glossary

- Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER)

It is the largest eukaryotic organelle and spreads in the cytoplasm from the nuclear membrane to the Golgi. It is usually divided in subdomains: the nuclear envelope, the rough ER, the smooth ER and the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment. The rough ER is characterized by a sheet-like morphology, named cisternae, and by the presence of membrane-associated ribosomes responsible for the synthesis of secretory and membrane proteins. The smooth ER, a tubular network devoid of ribosomes, is the site of lipid and steroid synthesis, carbohydrate metabolism, regulation of calcium levels and drug detoxification. Each subdomain is in communication with the others, forming an interconnected network of tubules, cisternae and vesicles delineated by membranes

- Golgi

eukaryotic organelle composed by membranes and vesicles. It is responsible for the post-translational modifications, storage of proteins and other macromolecules, and for their vesicular transport to other intracellular compartments or outside of the cell

- Langendorff perfusion system

It is a predominant ex vivo model used in cardiac pharmacological and physiological research, in which the isolated heart is perfused in a reverse fashion via the aorta. The backwards pressure of the flow closes the aortic valve and forces the perfusate into the coronary vasculature, supplying nutrients and oxygen to the heart for several hours after the explant

- Myogenic tone

is an intrinsic property of vascular smooth muscle cells consisting of contraction of blood vessels in response to a stretch induced by the increase in transmural pressure. This response is independent of neural or hormonal influences

- Nitric oxide (NO)

In the vessels NO is synthetized by the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). It is a lipophilic molecule easily diffusing through cell membranes and able to act on the vascular smooth muscle cells immediately beneath the endothelial cells to induce vasorelaxation by a cyclic GMP-mediated mechanism

- Neurite OutGrowth Inhibitor (NOGO)

so called because Nogo-A, one of three isoforms coded by Reticulon-4 gene (Rtn-4), was reported to repress neurite growth and synaptic plasticity in the central neuron system. To date, these findings remain controversial

- ORMDL

ORM1 (Saccharomyces Cerevisiae)-Like protein, where ORM stands for ORosoMucoiD

- Pathological cardiac hypertrophy

It consists in the increase of the mass of the heart following pathological stimuli, including hypertension, valve disease, myocardial infarction and genetic mutations. It is characterized by inflammation, fibrosis, alteration of the cardiac structure and functions and represents a risk factor for heart failure

- Physiological cardiac hypertrophy

It is a compensatory and reversible response of the heart to physiological stimuli, such as physical activity or pregnancy, characterized by increase in the heart mass with preservation of cardiac structure and function

- Pressure overload

it indicates a pathological state of the heart characterized by in excessive intraventricular pressure and deleterious systolic wall stress

- Shear stress

is the frictional force that blood flow induces on endothelial cells, the inner layer of the vessel wall

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:139–150. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buede R, et al. Cloning and characterization of LCB1, a Saccharomyces gene required for biosynthesis of the long-chain base component of sphingolipids. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4325–4332. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4325-4332.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagiec MM, et al. The LCB2 gene of Saccharomyces and the related LCB1 gene encode subunits of serine palmitoyltransferase, the initial enzyme in sphingolipid synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7899–7902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.7899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao C, et al. Suppressors of the Ca(2+)-sensitive yeast mutant (csg2) identify genes involved in sphingolipid biosynthesis. Cloning and characterization of SCS1, a gene required for serine palmitoyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21480–21488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagiec MM, et al. Sphingolipid synthesis: identification and characterization of mammalian cDNAs encoding the Lcb2 subunit of serine palmitoyltransferase. Gene. 1996;177:237–241. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss B, Stoffel W. Human and murine serine-palmitoyl-CoA transferase--cloning, expression and characterization of the key enzyme in sphingolipid synthesis. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hornemann T, et al. Cloning and initial characterization of a new subunit for mammalian serine-palmitoyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37275–37281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gable K, et al. Mutations in the yeast LCB1 and LCB2 genes, including those corresponding to the hereditary sensory neuropathy type I mutations, dominantly inactivate serine palmitoyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10194–10200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yard BA, et al. The structure of serine palmitoyltransferase; gateway to sphingolipid biosynthesis. J Mol Biol. 2007;370:870–886. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCampbell A, et al. Mutant SPTLC1 dominantly inhibits serine palmitoyltransferase activity in vivo and confers an age-dependent neuropathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3507–3521. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beattie AE, et al. Reconstitution of the pyridoxal 5’-phosphate (PLP) dependent enzyme serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) with pyridoxal reveals a crucial role for the phosphate during catalysis. Chem Commun (Camb) 2013;49:7058–7060. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43001d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasuda S, et al. Localization, topology, and function of the LCB1 subunit of serine palmitoyltransferase in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4176–4183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han G, et al. The topology of the Lcb1p subunit of yeast serine palmitoyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53707–53716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanada K, et al. Purification of the serine palmitoyltransferase complex responsible for sphingoid base synthesis by using affinity peptide chromatography techniques. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8409–8415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hornemann T, et al. Is the mammalian serine palmitoyltransferase a high-molecular-mass complex? Biochem J. 2007;405:157–164. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gable K, et al. Tsc3p is an 80-amino acid protein associated with serine palmitoyltransferase and required for optimal enzyme activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7597–7603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han G, et al. Identification of small subunits of mammalian serine palmitoyltransferase that confer distinct acyl-CoA substrate specificities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8186–8191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811269106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harmon JM, et al. Topological and functional characterization of the ssSPTs, small activating subunits of serine palmitoyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10144–10153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.451526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hjelmqvist L, et al. ORMDL proteins are a conserved new family of endoplasmic reticulum membrane proteins. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-6-research0027. RESEARCH0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breslow DK, et al. Orm family proteins mediate sphingolipid homeostasis. Nature. 2010;463:1048–1053. doi: 10.1038/nature08787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wadsworth JM, et al. The chemical basis of serine palmitoyltransferase inhibition by myriocin. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:14276–14285. doi: 10.1021/ja4059876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roelants FM, et al. Protein kinase Ypk1 phosphorylates regulatory proteins Orm1 and Orm2 to control sphingolipid homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19222–19227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116948108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Y, et al. Orm protein phosphoregulation mediates transient sphingolipid biosynthesis response to heat stress via the Pkh-Ypk and Cdc55-PP2A pathways. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:2388–2398. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-03-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimobayashi M, et al. TORC1-regulated protein kinase Npr1 phosphorylates Orm to stimulate complex sphingolipid synthesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:870–881. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-10-0753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chauhan N, et al. Regulation of sphingolipid biosynthesis by the morphogenesis checkpoint kinase Swe1. J Biol Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1074/jbc.A115.693200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantalupo A, et al. Nogo-B regulates endothelial sphingolipid homeostasis to control vascular function and blood pressure. Nat Med. 2015;21:1028–1037. doi: 10.1038/nm.3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.GrandPre T, et al. Identification of the Nogo inhibitor of axon regeneration as a Reticulon protein. Nature. 2000;403:439–444. doi: 10.1038/35000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oertle T, et al. Nogo-A inhibits neurite outgrowth and cell spreading with three discrete regions. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5393–5406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05393.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voeltz GK, et al. A class of membrane proteins shaping the tubular endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 2006;124:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fournier AE, et al. Identification of a receptor mediating Nogo-66 inhibition of axonal regeneration. Nature. 2001;409:341–346. doi: 10.1038/35053072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miao RQ, et al. Identification of a receptor necessary for Nogo-B stimulated chemotaxis and morphogenesis of endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10997–11002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602427103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hojjati MR, et al. Serine palmitoyl-CoA transferase (SPT) deficiency and sphingolipid levels in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1737:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Proia RL, Hla T. Emerging biology of sphingosine-1-phosphate: its role in pathogenesis and therapy. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1379–1387. doi: 10.1172/JCI76369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pappu R, et al. Promotion of lymphocyte egress into blood and lymph by distinct sources of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Science. 2007;316:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.1139221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venkataraman K, et al. Vascular endothelium as a contributor of plasma sphingosine 1-phosphate. Circulation research. 2008;102:669–676. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiong Y, et al. Erythrocyte-derived sphingosine 1-phosphate is essential for vascular development. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4823–4828. doi: 10.1172/JCI77685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christoffersen C, et al. Endothelium-protective sphingosine-1-phosphate provided by HDL-associated apolipoprotein M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9613–9618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103187108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murata N, et al. Interaction of sphingosine 1-phosphate with plasma components, including lipoproteins, regulates the lipid receptor-mediated actions. Biochem J. 2000;(352 Pt 3):809–815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee MJ, et al. Vascular endothelial cell adherens junction assembly and morphogenesis induced by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Cell. 1999;99:301–312. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiong Y, Hla T. S1P control of endothelial integrity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014;378:85–105. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-05879-5_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cantalupo A, Di Lorenzo A. Sphingolipids: de novo synthesis and signaling in blood pressure homeostasis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016 doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.233205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Camerer E, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate in the plasma compartment regulates basal and inflammation-induced vascular leak in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009 doi: 10.1172/JCI38575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christensen PM, et al. Impaired endothelial barrier function in apolipoprotein M-deficient mice is dependent on sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1. FASEB J. 2016 doi: 10.1096/fj.201500064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumaraswamy SB, et al. Decreased plasma concentrations of apolipoprotein M in sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndromes. Crit Care. 2012;16:R60. doi: 10.1186/cc11305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frej C, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and its carrier apolipoprotein M in human sepsis and in Escherichia coli sepsis in baboons. J Cell Mol Med. 2016 doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furchgott RF, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-derived relaxing and contracting factors. FASEB J. 1989;3:2007–2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukuhara S, et al. The sphingosine-1-phosphate transporter Spns2 expressed on endothelial cells regulates lymphocyte trafficking in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1416–1426. doi: 10.1172/JCI60746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim RH, et al. Export and functions of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:692–696. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Igarashi J, Michel T. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and modulation of vascular tone. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:212–220. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jung B, et al. Flow-regulated endothelial S1P receptor-1 signaling sustains vascular development. Dev Cell. 2012;23:600–610. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galvani S, et al. HDL-bound sphingosine 1-phosphate acts as a biased agonist for the endothelial cell receptor S1P1 to limit vascular inflammation. Sci Signal. 2015;8 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaa2581. ra79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mulders AC, et al. Activation of sphingosine kinase by muscarinic receptors enhances NO-mediated and attenuates EDHF-mediated vasorelaxation. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;104:50–59. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roviezzo F, et al. Essential requirement for sphingosine kinase activity in eNOS-dependent NO release and vasorelaxation. FASEB J. 2006;20:340–342. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4647fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kamiya T, et al. Role of Ca2+ -dependent and Ca2+ -sensitive mechanisms in sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced constriction of isolated porcine retinal arterioles in vitro. Exp Eye Res. 2014;121:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hemmings DG, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate acts via rho-associated kinase and nitric oxide to regulate human placental vascular tone. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:88–94. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hudson NK, et al. Modulation of human arterial tone during pregnancy: the effect of the bioactive metabolite sphingosine-1-phosphate. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:45–52. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.060681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lim M, et al. The role of sphingosine kinase 1/sphingosine-1-phosphate pathway in the myogenic tone of posterior cerebral arteries. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bolz SS, et al. Sphingosine kinase modulates microvascular tone and myogenic responses through activation of RhoA/Rho kinase. Circulation. 2003;108:342–347. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080324.12530.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peter BF, et al. Role of sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphohydrolase 1 in the regulation of resistance artery tone. Circulation research. 2008;103:315–324. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoefer J, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate-dependent activation of p38 MAPK maintains elevated peripheral resistance in heart failure through increased myogenic vasoconstriction. Circulation research. 2010;107:923–933. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang A, et al. Ceramide mediates inhibition of the Akt/eNOS pathway by high levels of glucose in human vascular endothelial cells. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2013;26:31–38. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2012-0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang QJ, et al. Ceramide mediates vascular dysfunction in diet-induced obesity by PP2A–mediated dephosphorylation of the eNOS-Akt complex. Diabetes. 2012;61:1848–1859. doi: 10.2337/db11-1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith AR, et al. Age-related changes in endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation and nitric oxide dependent vasodilation: evidence for a novel mechanism involving sphingomyelinase and ceramide-activated phosphatase 2A. Aging Cell. 2006;5:391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bharath LP, et al. Ceramide-Initiated Protein Phosphatase 2A Activation Contributes to Arterial Dysfunction In Vivo. Diabetes. 2015;64:3914–3926. doi: 10.2337/db15-0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li H, et al. Dual effect of ceramide on human endothelial cells: induction of oxidative stress and transcriptional upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2002;106:2250–2256. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000035650.05921.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Freed JK, et al. Ceramide changes the mediator of flow-induced vasodilation from nitric oxide to hydrogen peroxide in the human microcirculation. Circulation research. 2014;115:525–532. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spijkers LJ, et al. Hypertension is associated with marked alterations in sphingolipid biology: a potential role for ceramide. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li X, et al. Ceramide in redox signaling and cardiovascular diseases. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;26:41–48. doi: 10.1159/000315104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O’Neill SM, et al. C(6)-Ceramide-Coated Catheters Promote Re-Endothelialization of Stretch-Injured Arteries. Vasc Dis Prev. 2008;5:200–210. doi: 10.2174/156727008785133809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Altura BM, et al. Sphingomyelinase and ceramide analogs induce vasoconstriction and leukocyte-endothelial interactions in cerebral venules in the intact rat brain: Insight into mechanisms and possible relation to brain injury and stroke. Brain Res Bull. 2002;58:271–278. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00772-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zheng T, et al. Sphingomyelinase and ceramide analogs induce contraction and rises in [Ca(2+)](i) in canine cerebral vascular muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1421–H1428. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.5.H1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Knapp M, et al. Plasma sphingosine-1-phosphate concentration is reduced in patients with myocardial infarction. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2009;15:CR490–CR493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Knapp M, et al. Sustained decrease in plasma sphingosine-1-phosphate concentration and its accumulation in blood cells in acute myocardial infarction. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2013;106:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sutter I, et al. Decreased phosphatidylcholine plasmalogens--A putative novel lipid signature in patients with stable coronary artery disease and acute myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis. 2016;246:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Egom EE, et al. Serum sphingolipids level as a novel potential marker for early detection of human myocardial ischaemic injury. Front Physiol. 2013;4:130. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sattler KJ, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate levels in plasma and HDL are altered in coronary artery disease. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:821–832. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Argraves KM, et al. S1P, dihydro-S1P and C24:1-ceramide levels in the HDL-containing fraction of serum inversely correlate with occurrence of ischemic heart disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:70. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jing XD, et al. The relationship between the high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-associated sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and coronary in-stent restenosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;446:248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Klyachkin YM, et al. Pharmacological Elevation of Circulating Bioactive Phosphosphingolipids Enhances Myocardial Recovery After Acute Infarction. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:1333–1343. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Knapp M, et al. Myocardial infarction differentially alters sphingolipid levels in plasma, erythrocytes and platelets of the rat. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107:294. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0294-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Theilmeier G, et al. High-density lipoproteins and their constituent, sphingosine-1-phosphate, directly protect the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo via the S1P3 lysophospholipid receptor. Circulation. 2006;114:1403–1409. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Karliner JS. Sphingosine kinase and sphingosine 1-phosphate in the heart: a decade of progress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Means CK, Brown JH. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor signalling in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:193–200. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Means CK, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate S1P2 and S1P3 receptor-mediated Akt activation protects against in vivo myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2944–2951. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01331.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang J, et al. Signals from type 1 sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors enhance adult mouse cardiac myocyte survival during hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3150–H3158. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00587.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cannavo A, et al. Targeting cardiac beta-adrenergic signaling via GRK2 inhibition for heart failure therapy. Front Physiol. 2013;4:264. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chae SS, et al. Constitutive expression of the S1P1 receptor in adult tissues. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2004;73:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Forrest M, et al. Immune cell regulation and cardiovascular effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor agonists in rodents are mediated via distinct receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:758–768. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.062828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Keul P, et al. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor 1 Regulates Cardiac Function by Modulating Ca2+ Sensitivity and Na+/H+ Exchange and Mediates Protection by Ischemic Preconditioning. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pugach EK, et al. Prolonged Cre expression driven by the alpha-myosin heavy chain promoter can be cardiotoxic. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;86:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yeh CC, et al. Sphingolipid signaling and treatment during remodeling of the uninfarcted ventricular wall after myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1193–H1199. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01032.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li N, Zhang F. Implication of sphingosin-1-phosphate in cardiovascular regulation. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2016;21:1296–1313. doi: 10.2741/4458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Robert P, et al. EDG1 receptor stimulation leads to cardiac hypertrophy in rat neonatal myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1589–1606. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sekiguchi K, et al. Sphingosylphosphorylcholine induces a hypertrophic growth response through the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade in rat neonatal cardiac myocytes. Circulation research. 1999;85:1000–1008. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.11.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang Y, et al. Endothelial Nogo-B regulates sphingolipid biosynthesis to promote pathological cardiac hypertrophy during chronic pressure overload. JCI Insight. 2016;1 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.85484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Park TS, Goldberg IJ. Sphingolipids, lipotoxic cardiomyopathy, and cardiac failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2012;8:633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Russo SB, et al. Sphingolipids in obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic disease. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2013:373–401. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-1511-4_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jiang XC, et al. Sphingolipids and cardiovascular diseases: lipoprotein metabolism, atherosclerosis and cardiomyopathy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;721:19–39. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0650-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee SY, et al. Cardiomyocyte specific deficiency of serine palmitoyltransferase subunit 2 reduces ceramide but leads to cardiac dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18429–18439. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.296947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Newton J, et al. Revisiting the sphingolipid rheostat: Evolving concepts in cancer therapy. Exp Cell Res. 2015;333:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Parra V, et al. Calcium and mitochondrial metabolism in ceramide-induced cardiomyocyte death. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1832:1334–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dyntar D, et al. Glucose and palmitic acid induce degeneration of myofibrils and modulate apoptosis in rat adult cardiomyocytes. Diabetes. 2001;50:2105–2113. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.9.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schulze PC, et al. Lipid Use and Misuse by the Heart. Circulation research. 2016;118:1736–1751. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.306842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yagyu H, et al. Lipoprotein lipase (LpL) on the surface of cardiomyocytes increases lipid uptake and produces a cardiomyopathy. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;111:419–426. doi: 10.1172/JCI16751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Park TS, et al. Ceramide is a cardiotoxin in lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. Journal of lipid research. 2008;49:2101–2112. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800147-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Russo SB, et al. Ceramide synthase 5 mediates lipid-induced autophagy and hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3919–3930. doi: 10.1172/JCI63888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yu J, et al. Ceramide is upregulated and associated with mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kuwabara Y, et al. MicroRNA-451 exacerbates lipotoxicity in cardiac myocytes and high-fat diet-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice through suppression of the LKB1/AMPK pathway. Circulation research. 2015;116:279–288. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Noyan-Ashraf MH, et al. A glucagon-like peptide-1 analog reverses the molecular pathology and cardiac dysfunction of a mouse model of obesity. Circulation. 2013;127:74–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.091215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang L, et al. Cardiac diacylglycerol accumulation in high fat-fed mice is associated with impaired insulin-stimulated glucose oxidation. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89:148–156. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Baranowski M, et al. Myocardium of type 2 diabetic and obese patients is characterized by alterations in sphingolipid metabolic enzymes but not by accumulation of ceramide. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:74–80. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900002-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chokshi A, et al. Ventricular assist device implantation corrects myocardial lipotoxicity, reverses insulin resistance, and normalizes cardiac metabolism in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2012;125:2844–2853. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.060889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]