Abstract

Objectives:

To elaborate the desired qualities, traits, and styles of physician’s leadership with a deep insight into the recommended measures to inculcate leadership skills in physicians.

Methods:

The databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library were searched for the full-text English-language articles published during the period 2000-2015. Further search, including manual search of grey literature, was conducted from the bibliographic list of all included articles. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) keywords “Leadership” AND “Leadership traits” AND “Leadership styles” AND “Physicians’ leadership” AND “Tomorrow’s doctors” were used for the literature search. This search followed a step-wise approach defined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The retrieved bibliographic list was analyzed and non-relevant material such as abstracts, conference proceedings, letters to editor, and short communications were excluded. Finally, 21 articles were selected for this review.

Results:

The literature search showed a number of leadership courses and formal training programs that can transform doctors to physician leaders. Leaders can inculcate confidence by integrating diverse views and listening; supporting skillful conversations through dialogue and helping others assess their influence and expertise. In addition to their clinical competence, physician leaders need to acquire the industry knowledge (clinical processes, health-care trends, budget), problem-solving skills, and emotional intelligence.

Conclusion:

This review emphasizes the need for embedding formal leadership courses in the medical curricula for fostering tomorrow doctors’ leadership and organizational skills. The in-house and off-campus training programs and workshops should be arranged for grooming the potential candidates for effective leadership.

Leadership, a seemingly desirable competency, has not been clearly elucidated in the literature. Leadership; in its essence, is the capability to explicitly articulate a roadmap and to motivate others to focus their efforts on achieving the desired goals.1 It is also the ability to get extraordinary achievement from ordinary people;2 hence, leadership having a galvanic role in everyday life, being a fundamental component of our roles as professionals, academics, and clinicians. Leadership is the vision and mission to be something more than average. Denehy3 has rightly quoted that a “leader is one who knows the way, goes the way, and shows the way”. Leadership is more experienced, learned and developed than, as wrongly perceived, only an innate and inherent ability. Possessing an inherent ability for leadership gives a great advantage and can be considered as a faster track to leadership. The key roles of leadership involve creating a vision and a sense of community to inspire others to greatness.4 Moreover, leading with high energy and boundless enthusiasm motivates others and creates a sense of purpose. It is noteworthy that leadership is not the same as management. The key factor that distinguishes a manager from a leader is the leader’s capability to create a milestone for future action plans and to inspire physicians to perform through collaborative work. Such leadership potential and its consequent work can be executed by a clear understanding on why things ought to be changed.5 The value of leadership among physicians is becomes more significant as medical field indigenously requires a complex framework of clinical knowledge, industry experience, administrative portfolios, and emotional intelligence. Despite its paramount nature, medical field that is facing a crisis of true leadership.6 There are celebrity physicians and giants in health-care organizations, but few leaders. The managers are simulating like leaders of medical profession that seems to represent the medical industry.7 In effective leadership, opportunities must be offered to other people to receive recognition, praise, and increased confidence in their performances. This is facilitated by motivating achievable tasks, creating a sense of history and hope, and leading to a collective vision for the future. The current systematic review elaborates physician’s leadership qualities, traits, preferences, and diverse leadership styles. An account of the leadership development models is also provided, with particular attention to the significance of leadership for the physicians and physicians in training.

Methods

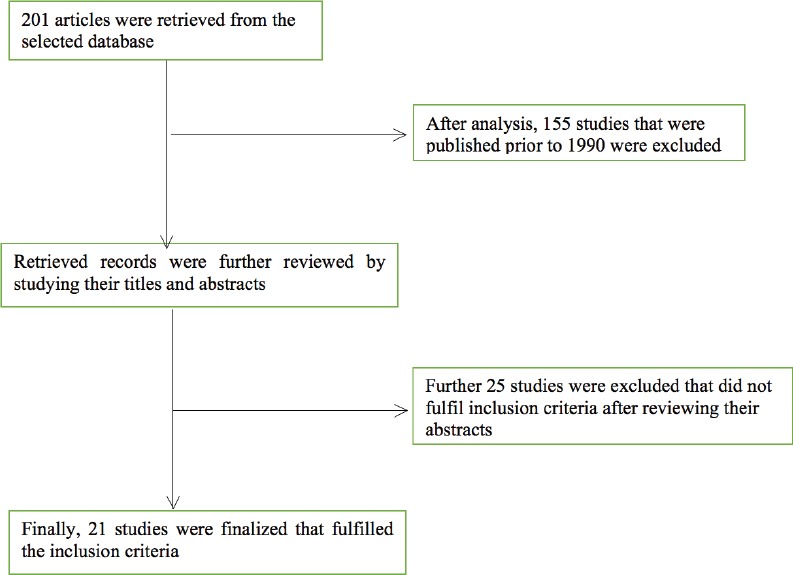

We conducted this systematic review in December 2015 using the databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)8 format 8. English language articles, published during 2000-2015 were searched by connecting Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) keywords: “Leadership” AND “Leadership traits” AND “Leadership styles” AND “Physicians’ leadership” AND “Tomorrow’s doctors”. Additional studies were also searched from the reference lists of all included articles. Manual search of the literature was also conducted that retrieved additional articles. This search brought a total of 201 studies. Of this, 155 studies were excluded as these studies were published before 2000. A detailed flowchart elaborating mechanism for the final selection of 21 articles is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the selection of studies on physician’s leadership

Results

The following sections elaborate the defined leadership qualities, traits, styles, and skills as searched from the published literature.

I. Qualities of a leader

Leaders have the ability to identify needs and devise action plans to achieve their intended targets in improving a situation or setting.9 Leaders can articulate problems clearly, and bring peers on board in addressing the identified concerns and issues. Leaders have a vision of what they want the future to look like and the measures that they need take in order to realize that vision. Leaders are able to inculcate an environment of teamwork and to delegate the job to the qualified team members. Leaders do not create followers, rather they create more leaders. An effective leader acknowledges the team members for a job well done, regardless of whether the team was able to completely reach the set goals, or not. A leader is capable of developing the best out of his team members; leadership is regarding “we” and not “me”.

The described qualities in a physician leader can be observed while he performs his services as a team leader, takes decision and shares vision on patients management, respects patient-physician relationships, follows interprofessional practice across disciplines, knows financial and administrative implications of innovative strategies in health-care, and openly acknowledges the team’s achievements.

In addition, a genuine leader is expected to have the desirable qualities like: (i) honesty, (ii) competency, (iii) forward-looking, (iv) inspiration, (v) intelligence, (vi) fair-mindedness, (vii) broad-mindedness, (viii) courage, (ix) straightforwardness, and (x) imagination.10 Leadership skills involve strong judgment, sound communication, ability to convince others and be convinced, negotiation, leading by role modeling, and possess confidence and skills in developing the job done in defined timelines and standards.

II. Leadership traits

Traits are innate, or heritable qualities of an individual. Published literature has described a number of traits such as behaviors, physical abilities, power relationships, or elements of a given situation, which contribute to an individual’s ability to influence followers in accomplishing the desired tasks.11 Historically, traits have been referred to personality characteristics. However, there are a myriad of contrasting skills that distinguish leaders from non-leaders. Such skills not only include the personality attributes but also cognitive, social and problem-solving skills that enable them to tackle and resolve the problems even before they happen.12 A wealth of leadership traits has been elaborated in literature.

Leadership practices inventory (LPI)

Kouzes and Posner13 grounded a behavior-based model of leadership for organizations. The following 5 behavior-based exceptional leadership practices are described; a) Challenging the process: Leaders accept the challenge, are ready to take risks, and have the ability to experiment innovations while accomplishing the desired objectives. b) Inspiring a shared vision: Leaders are capable of creating a clear sketch of the future with initiatives and, through dialogue, motivate others to strive for that future.14 Besides, timely initiatives differentiate genuine leaders from routine workers. c) Enabling others to act: Leaders empower other members of the team, share information, and delegate authority, instead of hoarding them.15 d) Modeling the way: Leaders demonstrate consistency between what one says and what one does. They lead by example whether they intend to or not. They also celebrate small wins, which boosts confidence and courage for the future challenges. e) Encouraging the hearts: Leaders openly attribute others’ contributions in achieving the goals and thus building a supportive social network outside the traditional organizational framework. Glasow16 has argued that a competent leader has the courage to take a little more than his share of blame and enjoys a touch less than his share of reward.16

Physical traits

These include vitality and enthusiasm, substantial physical stamina, profound energy level, tolerance to stress, and exceptional workload.17 They need to be physically fit and remain fit for the job.

Genetic traits

Recently, a number of reports have claimed that both genetic and developmental domains (namely, work and family experiences) exert substantial impact in deciding whether certain individuals would take leadership roles, or would remain stagnant.18

Gender traits

Several studies have reiterated the importance of the relationship between leadership and gender and have shown that individuals from diverse and multi-dimensional backgrounds possessing stereotypically masculine traits performed as effective leaders, in contrast to the feminine traits.19,20 These stereotypes maintain that women are often considered weak for the leadership posts. However, a number of competent women have proven themselves to be well-known effective leaders worldwide. Derue et al21 performed a meta-analysis to study an integrative trait-behavioral strategy for effective leadership by evaluating the relative validity of leader traits (gender, intelligence, personality), and behaviors across 4 effective leadership parameters; leader effectiveness, group work, follower job satisfaction, and satisfaction with leader. In the study, the reported behaviors of leaders that could count towards effective leadership showed significant variations than other leader traits.

III. Leadership styles

A number of leadership styles fitting in the managerial grid have been shared in the literature:22 i) Authoritarian leadership: This kind of leaders are known by their intolerance to different opinion and unexpected challenges. They are used to take independent decisions without engaging other members of the team.23 ii) Directive leadership: Leaders represent a prototypical traditional boss who performs through a highly executive style.24 Relying only on their personal judgments, directive leaders pass orders to subordinates and, unfortunately, look forward to their unconditional compliance. They delegate followers’ roles and provide guidelines for performing the tasks. iii) Shared leadership: In this situation, the team members are completely engaged by the team leadership and they have the liberty to influence and supervise their peers with a view to maximize the group output.25 iv) Democratic leadership: Leaders encourage group participation, discussion and shared decisions. They build organizational flexibility and responsibility and help generate innovative ideas.26 Reciprocally, by listening to the team members, democratic leaders earn the chance to understand the philosophy of making the best decision.

Although the literature has described the outlined taxonomy of authoritative and directive leadership styles, per se, this stand against the real definition of leadership. By and large, shared and democratic leadership style is considered to be superior to other styles. However the performance of democratic leaders succumb during crisis. All other styles reflect dictators’ approaches of running the organizations. The first 2 types are more of managerial than leadership styles. This is because leaders create leaders, while managers create followers, and these 2 particular styles (authoritative and directive) would probably create more followers rather than leaders. In hospital settings, more physician leaders are desired than managers as leaders would inculcate professional and skilled expertise rather than mere administrative support. On the other hand, some orthodox leaders change their styles and switch from one style to another based on the situation, which may confuse their subordinates.

IV. Developing leadership skills

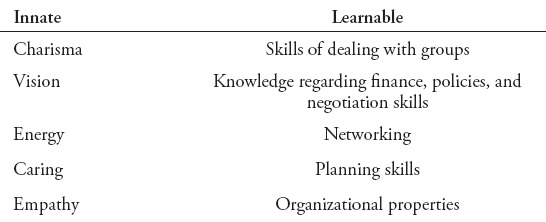

Leadership development involves a process of capacity building in order to nurture the leaders in anticipating unforeseen challenges and in tackling complex situations.27 Lord et al,28 have purposed that the development of leadership performance should be pitched in a structured and progressive hierarchy that moves from novice to intermediate and, finally, to expert and skillful level. A genuine leader is the one with exceptional talent and potential to master leadership competencies during the course of their professional career. A good leader is capable of using several strategies with different people, copes well with uncertainty, is a good listener and surrounds himself with great people (Table 1). Interestingly, a study has argued that if team leaders have not discarded a major proposal, or have not acquired a new proposal in the last few years, we need to check their pulse as they may be dead!29 This brings up an important concern on the emerging challenges from ageing population with multi-dimensional expectations and needs. The physician leaders are expected to keep pace with the evolving needs and challenges in the medical field.

Table 1.

The qualities and competencies of leadership.32

Learning leadership skills is akin to learning swimming that cannot be learned by reading only as one needs to get wet. Leadership skills are difficult to develop using conventional teaching strategies such as course books, seminars and lectures as there is no sufficient knowledge regarding leadership theories in these didactic educational strands. Hence, mere knowledge on principles of leadership, didactic classroom educational strategies, and many prototypical models do not provide successful leadership practices in challenging situations.30 In addition to building individual leaders by training on a set of skills, a complementary leadership framework involves an integrated social process where everyone in the community is engaged by performing differing roles.

Discussion

The implications of leadership for physicians

The model for executive leadership in academic medicine, specifically targeting for a successful health-care for the 21st century, introduced by Richman et al31 calls for versatility of the capabilities and management styles of physician leaders that can enhance their potential to successfully respond to the needs of all diverse disciplines working in an inter-professional environment. Effective physician leadership is critical to mobilize health-care facilities towards accomplishment of intended outcomes. Most physicians play varying leadership roles during their routine clinical practice of ward rounds, operating rooms, administrative fixtures, and difficult situations.

The commitment required to develop investigative and health-care professional talents and to achieve academic conventions might attract the physicians’ attention towards attaining the leadership skills; thus potentially jeopardizing their leadership capabilities. Taylor et al,32 conducted a structured, interview-based, qualitative research to explore the perception of current and aspiring physician leaders in terms of their specific leadership needs in the health-care facilities. The respondents proposed that knowledge, professional skills, emotional intelligence, and vision were the basic ingredients for effective leadership that play crucial roles in achieving success for the aspiring physician leaders. The findings of the study demand the inclusion of emotional intelligence competencies in the medical curricula and to reduce formal pedagogical strategies in favor of interactive and problem-based programs. Furthermore, the role of social constructivism, a sociological theory of knowledge, which implies that the development of human skills is socially situated and knowledge is gained through interaction with others, in teaching leadership skills has been stressed.33

Other evidence-based studies have emphasized the inclusion of training models on emotional intelligence, strategic planning, and administrative skills in the current undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula.34 Case discussions, applying new principles to real problems or dilemmas, debate, role-play, and simulations are recommended strategies for developing leadership strategies.35 Available reports in the literature for physician leadership development courses suggest a preference for a highly interactive and integrative format.36 Nine unique characteristics, with varying combinations, have been attributed to physicians’ leadership in health-care organizations: i) charisma, ii) individual considerations, iii) intellectual performance, iv) courage, v) dependability, vi) flexibility, vii) integrity, viii) judgment, and ix) respect for others.37 The servant leader model for excellent health-care is best applied to the leadership in physicians; “servant leader have passion for the mission because the vision is so paramount in their lives that they have literally become servant to it”.38 In their endeavor to become an established servant leader, physicians should ambitiously embrace the challenge of passion in serving the ailing community. Since leaders represent, serve, and deliver in their societies, they are accountable to the societies for their actions and performances. Social accountability is considered as an implicit expectation that one may be called on to justify one’s actions to others.39 This role tends to motivate reflection on one’s own decisions and behaviors. Identification of social accountability of leadership is a remarkable approach in predicting leaders’ team orientation and careful delivery of services.40 Therefore, the emerging capacity building and effective leadership development implies social systems to help build commitments among members of a community.41 Leadership development focuses on the interplay between the individual, the situation and the social and organizational environment.42 Ironically, health-care institutions are expanding dynamic facilities that pose special leadership challenges to physicians. a) Health-care institutions are complex organizations, performing with many different professional work forces.43 b) The traditional characteristics of physicians education and training do not allow them to develop the qualities of leadership such as collaboration.44 c) The external environment (namely, insurance, reimbursement, financial regulations) is extremely hostile and difficult to manage. d) The aims of service delivery in such institutions are potentially competing due to several factors such as the stress of expenses, health-care delivery, and service quality.

The problems are further compounded by the lack of formal teaching and training of physicians in nurturing their leadership skills. Physician leaders often receive little, if any, formal training in leadership or management on the journey from medical school to leadership. At the same time, the traditional medical school curriculum and residency training programs with their focus on clinical skills and scientific education have not left room for leadership training. Consequently, majority of physicians lack certain leadership skills such as strategic and tactical development, persuasive communication, negotiation, financial entrepreneurs, team building, conflict resolution, and interviewing skills.45 In order to accommodate the recent demand of providing more value-added services, it is imperative for healthcare executives to identify and then groom those physicians best suited to serve as leaders of health-care institutions.

It is therefore necessary that all physicians receive formal leadership training as all of them perform as leaders in their own capacities. Some institutions respond to the need for physician leadership by providing opportunities for their staff to attend off campus administrative and leadership training programs. Many institutions, however, address this need by offering their own in-house leadership programs in the form of workshops and symposia.46 The programs might be designed to assist physicians in the smooth transition from the mind set of clinicians to managers, then to develop leadership skills in young physicians, and to prepare physicians to professionally cope with the changes resulting from the evolving health-care environment. Coaching or mentoring from an experienced leader and on-job experience have been quoted as the most effective strategies for developing physician leadership competencies.47

Recommendations

This systematic review reiterates the need to embed certain problem-based learning educational domains and instructional strategies in the existing undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula focusing on developing emotional intelligence competencies and the skills for strategic planning, and organizational awareness among physicians. The training in debate, role-play, and simulations are the recommended strategies for developing physicians’ leaders. The health-care policy makers and medical educators should identify those physicians with leadership potential and should aim to nurture their professional training for attaining leadership competencies. The learning conventions for in-house leadership programs in the form of workshops and symposia and opportunities to physicians to attend off-campus leadership and administrative training programs will help foster the acquisition of the desired physicians’ leadership skills.

Study limitations

This research work signals a roadmap for developing skills and competencies for physicians’ leadership. However, this paper does not validate the outcome measures that can reflect the significance of effective leadership in health-care system. A review of future evidence-based studies regarding the effectiveness of physicians’ leadership can endorse such findings.

In conclusion, this research work shows that the competent and effective leaders are more likely to be respected by their followers as they practice open 2-way communication, share critical information, and freely disclose their perceptions and feelings with the people they work with. The complexity and diverse characteristics of health-care institutions, versatile training experiences of physicians, and sensitive nature of the physicians’ tasks demand special leadership skills such as the knowledge of the health-care industry, emotional intelligence, strategic planning, flexibility, and vision. Leadership workshops and courses to groom potentially effective leaders can win these desirable

Footnotes

References

- 1.Mathews J. Toward a conceptual model of global leadership. IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2016;15:38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eagly AH, Chin JL. Diversity and leadership in a changing world. Am Psychol. 2010;65:216. doi: 10.1037/a0018957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denehy J. Leadership characteristics. J Sch Nurs. 2008;24:107–110. doi: 10.1177/1059840512341234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krause R, Semadeni M. Last dance or second chance? Firm performance, CEO career horizon, and the separation of board leadership roles. Strategic Management Journal. 2014;35:808–825. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cochran J, Kaplan GS, Nesse RE. Physician leadership in changing times. Healthc (Amst) 2014;2:19–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar R. The leadership crisis of medical profession in India: ongoing impact on the health system. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4:159. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.154621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fulop L, Executive G, Waight P. Leadership and Clinician Managers: Individual or Post-individual? [Updated 2015; Accessed 2015 December 2015]. Available from URL: http://www98.griffith.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/handle/10072/1↘/49906_1.pdf;jsessionid=1200F592DBC91E5CB3C955B4C1E5CB8C?sequence=1 .

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perks S, May J. Proceedings of International Academic Conferences. International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences. Czech Republic (CR): International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences Prague; 2015. Change leadership styles and qualities necessary to drive environmental sustainability in South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Posner BZ, Kouzes JM. Ten lessons for leaders and leadership developers. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 1997;3:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casimir G, Waldman DA. A cross cultural comparison of the importance of leadership traits for effective low-level and high-level leaders Australia and China. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management. 2007;7:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansen R. Leaders make the future: Ten new leadership skills for an uncertain world. Oakland (CA): Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. The Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI): Participant’s Workbook. New Jersey (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollander EP. Leadership, followership, self, and others. The Leadership Quarterly. 1992;3:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du Plessis A, Carroll A, Gillies RM. Understanding the lived experiences of novice out-of-field teachers in relation to school leadership practices. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education. 2015;43:4–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glasow A. Success is simple. Do what’s right, the right way at the right time. “Right makes might: Reviving ethics to improve your business. 2007:59. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bass BM, Stogdill RM. Handbook of leadership. Theory, Research & Managerial Applications. 3rd ed. New York (NY): The Free Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li WD, Arvey RD, Song Z. The influence of general mental ability, self-esteem and family socioeconomic status on leadership role occupancy and leader advancement: The moderating role of gender. The Leadership Quarterly. 2011;22:520–534. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell GN, Butterfield DA, Parent JD. Gender and managerial stereotypes: have the times changed? Journal of Management. 2002;28:177–193. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schein VE, Müller R, Lituchy T, Liu J. Think manager—think male: A global phenomenon? Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1996;17:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeRue DS, Nahrgang JD, Wellman N, Humphrey SE. Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Personnel Psychology. 2011;64:7–52. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blake RR, Mouton JS. Management by Grid®principles or situationalism: Which? Group & Organization Management. 1981;6:439–455. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuh SC, Zhang X-a, Tian P. For the good or the bad? Interactive effects of transformational leadership with moral and authoritarian leadership behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics. 2013;116:629–640. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorinkova NM, Pearsall MJ, Sims HP. Examining the differential longitudinal performance of directive versus empowering leadership in teams. Academy of Management Journal. 2013;56:573–596. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ensley MD, Hmieleski KM, Pearce CL. The importance of vertical and shared leadership within new venture top management teams: Implications for the performance of startups. The Leadership Quarterly. 2006;17:217–231. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strandburg-Peshkin A, Farine DR, Couzin ID, Crofoot MC. Shared decision-making drives collective movement in wild baboons. Science. 2015;348:1358–1361. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siewiorek A, Saarinen E, Lainema T, Lehtinen E. Learning leadership skills in a simulated business environment. Computers & Education. 2012;58:121–135. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lord RG, Hall RJ. Identity, deep structure and the development of leadership skill. The Leadership Quarterly. 2005;16:591–615. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goleman D. Leadership that gets results 2000. Leadership. 2012;10:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chreim S, Langley A, Comeau-Vallée M, Huq J-L, Reay T. Leadership as boundary work in healthcare teams. Leadership. 2013;9:201–228. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richman RC, Morahan PS, Cohen DW, McDade SA. Advancing women and closing the leadership gap: the Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine (ELAM) program experience. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:271–277. doi: 10.1089/152460901300140022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor CA, Taylor JC, Stoller JK. Exploring leadership competencies in established and aspiring physician leaders: an interview-based study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:748–754. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0565-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flint ES. Engaging social constructivist teaching in the diverse learning environment;perspectives from a first year faculty member. Higher Education for the Future. 2016;3:38–45. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veronesi MC, Gunderman RB. Perspective: the potential of student organizations for developing leadership: one school’s experience. Academic Medicine. 2012;87:226–229. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823fa47c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuo AK, Thyne SM, Chen HC, West DC, Kamei RK. An innovative residency program designed to develop leaders to improve the health of children. Academic Medicine. 2010;85:1603–1608. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eb60f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoller JK. Developing physician-leaders: Key competencies and available programs. J Health Adm Educ. 2008;25:307–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackson B, Parry K. A very short fairly interesting and reasonably cheap book about studying leadership. New Zealand (NZ): Sage Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenleaf RK. Servant leadership in business. Leading organizations: Perspectives for a new era. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larkins SL, Preston R, Matte MC, Lindemann IC, Samson R, Tandinco FD, et al. Measuring social accountability in health professional education: Development and international pilot testing of an evaluation framework. Medical Teacher. 2013;35:32–45. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.731106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giessner SR, van Knippenberg D, van Ginkel W, Sleebos E. Team-oriented leadership: The interactive effects of leader group prototypicality, accountability, and team identification. J Appl Psychol. 2013;98:658. doi: 10.1037/a0032445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popescu E. Providing collaborative learning support with social media in an integrated environment. World Wide Web. 2014;17:199–212. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meili R, Buchman S. Social accountability: at the heart of family medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:335–336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silversin J, Kornacki MJ. Leading Physicians Through Change: How to Achieve and Sustain Results. Physician Executive. 2012;38:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoller JK. Developing physician-leaders: a call to action. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:876–878. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1007-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Busari JO. Management and leadership development in healthcare and the challenges facing physician managers in clinical practice. The International Journal of Clinical Leadership. 2013;17:211–216. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Satiani B, Sena J, Ruberg R, Ellison EC. Talent management and physician leadership training is essential for preparing tomorrow’s physician leaders. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:542–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pradarelli JC, Jaffe GA, Lemak CH, Mulholland MW, Dimick JB. A leadership development program for surgeons: First-year participant evaluation. Surgery. 2016;160:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]