Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common complication of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and contributes to high rates of in-hospital adverse events. However, there are few contemporary studies examining rates of AF in the contemporary era of AMI or the impact of new-onset AF on key in-hospital and post-discharge outcomes. We examined trends in AF among 6,384 residents of Worcester, Massachusetts who were hospitalized with confirmed AMI during 7 biennial periods between 1999 and 2011. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to examine associations between occurrence of AF and various in-hospital and post-discharge complications. The overall incidence of AF complicating AMI was 10.8%. Rates of new-onset AF increased from 1999 to 2003 (9.8% to 13.2%), and declined thereafter. In multivariable adjusted models, patients developing new-onset AF following AMI were at higher risk for inhospital stroke [Odds Ratio (OR) 2.5, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 1.6–4.1], heart failure [OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.7 to 2.4], cardiogenic shock [OR 3.7, 95% CI 2.8–4.9] and death [OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.9 to 3.0] than patients without AF. Development of AF during hospitalization for AMI was associated with higher rates of readmission within 30-days after discharge [21.7% vs. 16.0%], but no significant difference was noted in early post-discharge 30-day all-cause mortality rates [8.3% vs. 5.1%]. In conclusion, new-onset AF following AMI is strongly related to in-hospital complications of AMI as well as higher short-term readmission rates.

Keywords: Stroke, Heart Failure, Re-admission, Outcomes, Epidemiology

Introduction

Atrial Fibrillation (AF) is the most common dysrhythmia, and the global prevalence of AF continues to rise with the aging of the population in many countries [1]. AF is a frequent complication of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and in prior studies of patients with AMI, has been linked to increased rates of heart failure, stroke, and death [2–5]. Over the last few decades, dramatic changes have occurred in how patients with AMI are diagnosed and treated. More sensitive troponin assays, early percutaneous revascularization and newer therapeutic options for medical management, have favorably reshaped the prognosis of patients with AMI [6]. Moreover, economic factors, including pay-for-performance and public reporting of adverse outcomes, as well as quality improvement programs have helped achieve better patient-related outcomes [7]. While these changes have had a favorable impact on overall in-hospital mortality among patients with AMI, studies suggest that the incidence of AF complicating AMI remains as common today as it was twenty years ago [3–5,8–10]. However, limited studies have examined recent trends in AF or its impact on traditional in-hospital and post-discharge short-term outcomes, especially from a community wide perspective. With the goal of filling knowledge gaps related to the descriptive epidemiology of AF in the contemporary era of AMI, we analyzed data from the population-based Worcester Heart Attack Study.

Methods

The Worcester Heart Attack Study (WHAS) is an ongoing, population-based, observational investigation examining long-term trends in the incidence, morbidity, in-hospital complications, as well as short and long-term mortality of patients hospitalized with AMI at all greater Worcester medical campuses [11, 12]. Our study population is comprised of 6,384 residents of the Worcester metropolitan area in central MA who were hospitalized with a discharge diagnosis of AMI at all Worcester Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA) hospitals during any of 7 biennial years from 1999 to 2011. There were originally 16 health care facilities that were included in the study. Recently, fewer hospitals (n=11) have been providing care to residents of central MA due to hospital closures, mergers, or conversion to long-term care facilities [13]. Among the present 11 hospitals, 3 were tertiary care/university-based medical centers where almost 85–90 % of patients with confirmed AMI had been hospitalized during the years under study with little variation in this proportion observed over time. Patients with a known history of AF, based on the review of information contained in medical records, were considered to have ‘Prevalent AF’ [n=493] and those who developed AF during their hospitalization for AMI were defined as having ‘Incident AF’ [n= 693].

Trained physicians and nurses abstracted data of eligible patients with confirmed AMI from hospital medical records. Information was collected about patients’ age, gender, previous co-morbidities, type of AMI (STEMI or NSTEMI, Q Wave vs. Non Q Wave), AMI order (initial vs. previous), physiologic parameters on admission (blood pressure, respiratory rate, etc.), in-hospital medications and in-hospital procedures. Data were also collected about occurrence of in-hospital complications such as stroke [14], heart failure [15], acute renal failure, cardiogenic shock [16], and death. Post discharge readmission rates were tabulated and post discharge mortality was evaluated by review of medical records for subsequent hospitalizations and a nationwide search of death certificates for residents of the Worcester metropolitan area. Medical records of residents of the Worcester metropolitan area admitted for possible AMI at all Worcester SMSA medical centers were individually reviewed and validated. The diagnosis of AMI was confirmed using pre-established diagnostic criteria [13].

The occurrence and timing of AF was determined for WHAS participants based on manual abstraction of clinical information from ambulance transport records, emergency admission notes and logs, progress notes, and all in-hospital 12-lead ECGs. Interpretation of ECG findings is not done in isolation as a computerized interpretation of each recorded ECG is performed at all participating greater Worcester hospitals in addition to an over-read by a board-certified clinical cardiologist. Prevalent AF was considered present if a history of AF was noted in the admission note or any progress note. The criteria used to define incident AF included: No documentation of history of AF and either a) AF deemed present by an interpreting cardiologist on any 12-lead ECG obtained during the index hospitalization [3,12], or b) new-onset AF documented in any clinical note during the index hospitalization. Patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) during hospitalization for AMI were excluded from the analysis since postoperative AF is common in patients who undergo CABG and is caused by different etiological factors and pathophysiological mechanisms [17].

Differences in characteristics of those with incident AF, prevalent AF, and no AF were examined through the use of chi-square test and ANOVA for discrete and continuous variables, respectively. Similar methods were used to examine differences in hospital and post-discharge outcomes according to hospital development of incident AF. Short-term prognosis in each of the periods under study was examined by calculating in-hospital complication and case-fatality rates. Multivariate logistic models were constructed, with accompanying odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), to examine trends in occurrence of incident AF over the study period. The odds of developing AF were adjusted for several potentially confounding demographic and clinical factors, including age, gender, race, history of angina, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, heart failure, hyperlipidemia, COPD, renal failure and AMI-associated characteristics. To examine the potential impact of infarct type (STEMI vs. NSTEMI), chronic kidney disease (CKD) and receipt of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) on the odds of developing AF, we conducted stratified analyses evaluating the odds of developing AF in the aforementioned groups. An additional series of multivariate logistic regression models was used to examine the association between occurrence of AF and in-hospital stroke, renal failure, heart failure, 30-day post discharge mortality, and 30-day readmission rates, while adjusting for the same set of covariates included in our prior analyses. We did not control for receipt of cardiac medications or coronary reperfusion strategies in the analyses due to the potential for confounding by treatment indication and lack of data on timing of administration of these therapies. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The baseline characteristics of the 6,384 study patients are shown in Table 1. Four hundred and ninety-three patients had AF prior to their AMI (7.7%), whereas 693 patients (10.8%) developed new-onset AF during their index AMI-related hospitalization.

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, Laboratory and Treatment Characteristics of Study Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction, further stratified by Atrial Fibrillation Status

| Characteristics | Incident AF (n=693) | Prevalent AF (n=493) | No AF (n=5,198) | P value in relation to No AF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age -Mean [SD] | 76.2 [11.4] | 79.8 [8.9] | 68.5 [14.5] | <0.001 |

| Age < 65 years | 15.7 % | 5.9 % | 38.1 % | <0.001 |

| Age 65–84 years | 55.8 % | 54.4 % | 44.7 % | <0.001 |

| Age >= 85 years | 28.4 % | 39.8 % | 17.3 % | <0.001 |

| Sex, % Men | 50.8 % | 54.4 % | 56.6% | 0.01 |

| White Race | 91.5 % | 94.5 % | 89.1 % | <0.001 |

| Angina Pectoris | 13.7 % | 18.3 % | 15 % | 0.08 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 21.9 % | 31.4 % | 17.7 % | <0.001 |

| COPD | 20.2 % | 26.4 % | 16.9 % | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 33.2 % | 36.3 % | 33.8 % | 0.48 |

| Heart failure | 24.4 % | 48.9 % | 22.5 % | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 52.4 % | 50.9 % | 56.6 % | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 74.5 % | 81.3 % | 71.1 % | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 12.5 % | 20.1 % | 11.1 % | <0.001 |

| AMI Type | ||||

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 38.1 % | 20.5 % | 35.4 % | <0.001 |

| Non ST-segment elevation Myocardial infarction | 61.9 % | 79.5 % | 64.6 % | <0.001 |

| Initial AMI | 70.9 % | 53.5 % | 64.6 % | <0.001 |

| Q Wave | 26.3% | 10.5 % | 21.9 % | <0.001 |

| Non Q Wave | 73.7 % | 89.5 % | 78.1% | <0.001 |

| Troponin I Peak in ng/mL – Mean [SD] | 28.1 [83.3] | 17.9 [44.4] | 18.1 [66.9] | <0.001 |

| Creatinine in mg/dl - Mean [SD] | 1.5 [1.1] | 1.6 [1] | 1.4 [1.1] | <0.001 |

| Factors at Admission | ||||

| Initial Heart Rate (bpm)-Mean [SD] | 91.6 [27.3] | 91.6 [24.2] | 84.9 [21.1] | <0.001 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) - Mean [SD] | 133.5 [31.9] | 134.7 [31.5] | 142.5 [31.3] | <0.001 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg)- Mean [SD] | 73.7 [19.4] | 73[18.4] | 77.8 [19.5] | <0.001 |

| Respiratory Rate (per minute)- Mean [SD] | 21.9 [6.3] | 22.1 [5.9] | 21 [5.5] | <0.001 |

| In-Hospital Medications | ||||

| Beta-blocker | 85.6 % | 86.8 % | 88.1 % | 0.13 |

| Aspirin | 90.0 % | 85.2 % | 91.9 % | <0.001 |

| Statin/Lipid Lowering Agents | 63.5 % | 55.8 % | 69 % | <0.001 |

| ACE-I/ARB | 62.5 % | 59.6 % | 62.6 % | 0.4 |

| Clopidogrel | 49.6 % | 37.3 % | 58.9 % | <0.001 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 33.2 % | 34.9 % | 19.1 % | <0.001 |

| Diuretic | 67.1 % | 75.7 % | 46.4 % | <0.001 |

| Digoxin | 34.1 % | 44.2 % | 10.9 % | <0.001 |

| Thrombolytics | 4.4 % | 2.0% | 6.3 % | <0.001 |

| Enoxaparin/Heparin | 27.1 % | 18.3 % | 19.8 % | <0.001 |

| Warfarin | 19.9 % | 40.8 % | 8.4 % | <0.001 |

| In-Hospital Procedures | ||||

| Percutaneous coronary Intervention | 37.2 % | 21.5 % | 44.8 % | <0.001 |

| Cardiac Catheterization | 48.1 % | 34.5 % | 59.5 % | <0.001 |

Note: All values are mean +- SD or % unless otherwise noted.

ACE-I/ARB= Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/Angiotensin receptor blocker

AMI= Acute myocardial infarction

COPD= Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

SD= Standard deviation

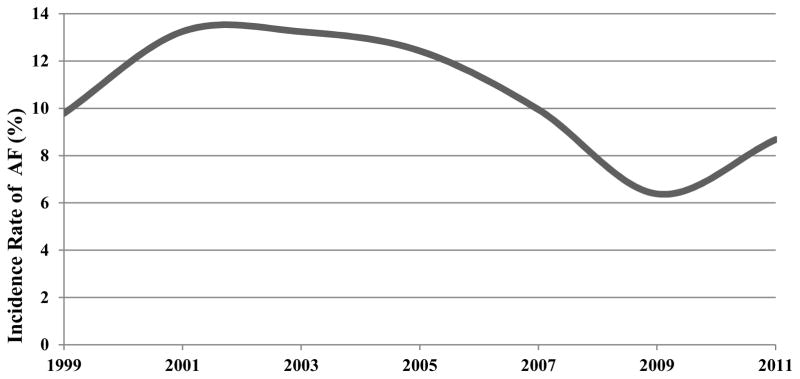

Rates of new-onset AF initially increased from 9.8% in 1999 to 13.2% in 2003, after which rates decreased to a nadir of 6.4% in 2009, before returning to near-baseline levels in the most recent study year 2011 (Figure 1). After controlling for several demographic factors, co-morbid conditions, AMI characteristics, and in-hospital complications, the odds of developing AF were highest in 2003 and lowest in 2009, but remained relatively stable throughout the other years under study (Table 2). Odds of developing AF over time did not vary significantly among groups stratified by PCI status, AMI type, or presence of CKD (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in the Incidence Rates of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients Hospitalized with Acute Myocardial Infarction AF= Atrial Fibrillation

Table 2.

Odds of Developing Atrial Fibrillation during Hospitalization for Acute Myocardial Infarction by Study Year

| Period | Patients | Crude OR with 95 % CI | Adjusted OR * with 95 % CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999† | 920 | 1.0 (Referent study year) | 1.0 |

| 2001 | 1065 | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) |

| 2003 | 998 | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 1.5 (1.1–2) |

| 2005 | 788 | 1.4 (1–1.9) | 1.3 (1–1.8) |

| 2007 | 755 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| 2009 | 680 | 0.6 (0.5–0.9) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) |

| 2011 | 685 | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) |

CI= Confidence interval

OR= Odds Ratio

Adjusted for age, gender, race, history of angina, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, heart failure, hyperlipidemia, COPD, renal failure and AMI-associated characteristics.

Patients who developed AF were older, more likely to be women and have a history of hypertension, heart failure, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and CKD than those who did not develop AF (Table 1). Although patients with incident AF had lower admission blood pressures and a higher heart rate, they were less likely to have undergone in-hospital procedures such as PCI and cardiac catheterization. Patients with incident AF were less likely to have been treated with aspirin, clopidogrel, beta-blockers, statins, or thrombolytics. On the other hand, a greater percentage of AMI patients with new-onset AF received digoxin, diuretics, calcium channel blockers, and anticoagulants (heparin and warfarin) (Table 1).

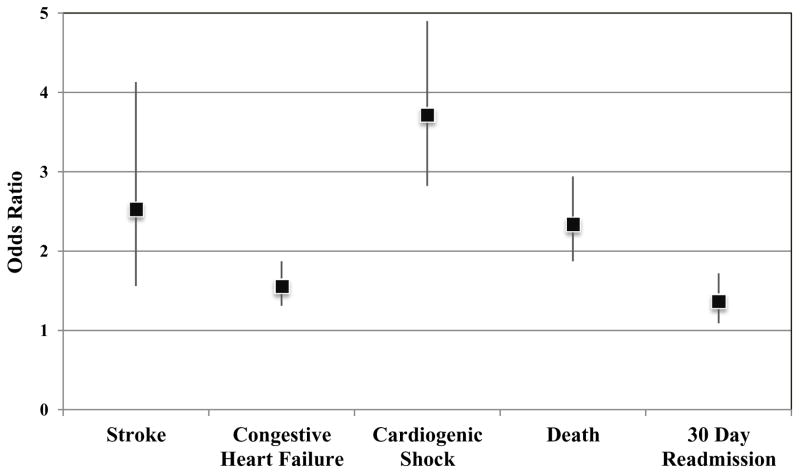

Patients developing AF were significantly more likely to have a hospital course characterized by the development of several complications such as stroke, heart failure, acute renal failure, and cardiogenic shock (Table 3). After adjusting for several demographic factors, co-morbid conditions, prior medical history, and AMI-associated characteristics, patients with incident AF remained at significantly higher risk for developing stroke [adjusted OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.6 to 4.1], heart failure [adjusted OR 2.0, 95 % CI 1.7 to 12.4] and cardiogenic shock [adjusted OR 3.7, 95 % CI 2.8 to 4.9] than were patients who remained free from AF during their hospitalization [p <0.001 for all] (Figure 2). Although limited by relatively small numbers of patients in each group, outcomes did not vary significantly among patients with incident AF further stratified by receipt of PCI, AMI type, or presence of CKD (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 3.

Overall Rates of In-Hospital and Post-Discharge Complications Among Patients Admitted for an Acute Myocardial Infarction, Further Stratified by Atrial Fibrillation Status.

| Characteristics | Incident AF n=693 | No AF n=5198 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Hospital Complications | |||

| Heart failure | 56.7 % | 41.8 % | <0.001 |

| Acute renal failure | 24.5 % | 12.0 % | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 3.6 % | 1.4 % | <0.001 |

| Recurrent myocardial infarction | 1.0 % | 0.7 % | 0.4 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 13.1 % | 4.0% | <0.001 |

| Death | 19.6 % | 7.9 % | <0.001 |

| Post-discharge Complications | |||

| 30-day rehospitalization | 21.7 % | 16 % | <0.001 |

| 30-day post-discharge death | 8.3 % | 5.1 % | <0.001 |

AF = Atrial Fibrillation

Figure 2.

Adjusted Odds of Developing In-Hospital Complications Among Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction and New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation as Compared to No Atrial Fibrillation (with accompanying 95% Confidence Intervals)

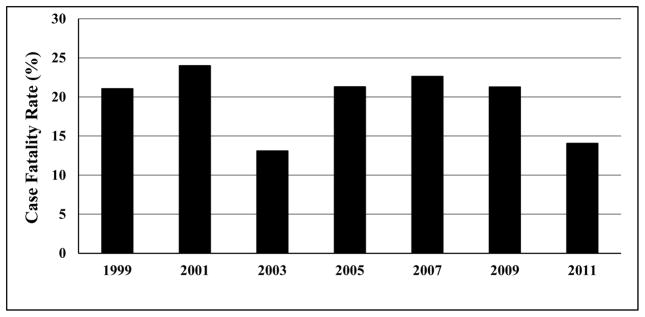

Patients with AMI complicated by AF had a significantly higher risk for dying during their hospitalization [OR 2.9, 95 % CI 2.3 to 3.5] compared with patients without AF. Even after multivariable adjustment for potential confounders, patients developing AF remained greater than 2-fold more likely to die during hospitalization [adjusted OR 2.3, 95 % CI 1.9 to 2.9]. We did not observe a significant decline in the case-fatality rates associated with new-onset AF between 1999 and 2011 (Figure 3), suggesting that AF exerted a consistent negative influence on the risk of dying during hospitalization for AMI throughout the study period.

Figure 3.

Trends in Hospital Case-Fatality Rates in Patients who Developed Atrial Fibrillation during Hospitalization for an Acute Myocardial Infarction

Patients developing new-onset AF had almost 50% higher crude odds of 30-day hospital readmission rates compared to those who did not develop AF [OR 1.5, 95 % CI 1.2 to 1.8]. After adjustment for confounding factors described previously, 30-day hospital readmission rates remained greater among patients with incident AF [adjusted OR 1.4, 95 % CI 1.1 to 1.7].

Compared to patients who did not develop AF, those who developed AF experienced higher 30-day death rates than did patients free from AF (8.3 % vs. 5.1 %), but multivariable adjustment for comorbidities associated with AF or death attenuated the association between incident AF and risk for dying within thirty days [adjusted OR 1.3, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.9].

Discussion

In our large, community-wide study involving more than 6,000 patients admitted to all regional medical centers with AMI between 1999 and 2011, we observed that new-onset AF remains a common and lethal complication of AMI. Perhaps because of its strong relations to other complications of AMI, including heart failure and stroke, AF was associated with higher risk for in-hospital death and readmission within 30-days.

Despite the increasing number of elderly people and associated cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidities in the United States, the present study showed that the overall incidence of AF (10.8%) appeared to be close to, but slightly higher than, that observed in older clinical trials of patients with AMI (rates 5–10%) [5, 8–10,18], and lower than rates from our prior population based analysis of earlier WHAS data (13%) [4]. We observed that the incidence rates of developing new-onset AF after AMI initially increased between 1999 to 2003, then declined until 2009. Our observation that the overall rates of new-onset AF among patients admitted for an AMI may be decreasing slightly was also seen in a population based study of 2,460 patients who were admitted with a diagnosis of AMI between 2004 and 2009, in which approximately 6% of patients suffering from AMI developed AF within 7 days [19]. Our previous analysis showed that the rates of incident AF steadily decreased during the 1990s [4]. This was attributed to increased use of effective cardiac medications and early coronary revascularization. However, incidence rates of AF appear to have plateaued, suggesting a threshold effect of evidence-based therapies presently used in the context of an AMI. Reasons for the higher rates of AF observed in our study in comparison to prior clinical trials include the older age of our study population, as well as the exclusion of some patients at high risk for AF (e.g., those with a history of stroke) from several of these clinical trials [8,9].

Despite being significantly older and having a greater prevalence of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidities, patients with new-onset AF were less likely to undergo cardiac diagnostic and revascularization interventions during their hospitalization for AMI than patients with AMI whose hospitalization was not complicated by AF. We speculate that this is likely due to the fact that patients with incident AF had a more complicated hospital course and were considered at higher risk for invasive treatment procedures, given the greater prevalence of comorbidities such as CKD and associated higher baseline creatinine levels.

We observed a greater-than 2-fold higher risk for acute stroke and death during hospitalization among patients admitted with an AMI and new-onset AF. Our results are consistent with those of the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events study where it was observed that patients with new-onset AF had a greater than 3-fold increased risk for dying during hospitalization for an acute coronary syndrome compared with those who did not develop AF [18]. Patients with new-onset AF following AMI were almost 2-times more likely to have a hospital course complicated by development of heart failure and more than 3 times more likely to develop cardiogenic shock, suggesting that incident AF exerts a strong influence on the risk for other important cardiovascular outcomes in patients hospitalized for AMI.

Our analysis showed that patients with incident AF were more likely to be readmitted to the hospital within 30 days after discharge than patients who did not develop AF. Hospital readmission results in significant financial loss and, in some cases, early hospital readmission is used as an indicator of poor hospital quality and is associated with financial penalties for hospital systems [7]. Thus, new-onset AF following AMI might identify a population that might benefit from targeted interventions to reduce readmission rates. In contrast to our prior studies, we did not observe a significant higher odds of dying among patients with AF within the first 30-days after discharge. The is perhaps due to greater adherence to guideline-directed therapies which may be positively influencing the prognosis of patients with AMI and AF [4].

Strengths of the present study include our population-based design that included all patients hospitalized with AMI in a well-characterized urban New England community. The large number of patients hospitalized with initial AMI, the validation of each individual case of possible AMI according to standardized criteria and inclusion of all regional hospitals in Worcester are additional strengths of this study. We were also able to control for several potentially confounding factors in examining changing trends in the magnitude and death rates associated with AF in patients hospitalized with AMI through regression modeling.

Our findings are limited, by lack of data on type of AF (paroxysmal, persistent or permanent), timing of development of AF during the hospital course, and our inability to examine whether time of occurrence of AF was associated with development of important complications of AMI, including stroke. There were too few cases of acute stroke to determine whether AF is associated with ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes. Although small in number, it is possible that a few patients presented to hospitals outside our network for subsequent admissions, leading to potential under-estimation of rehospitalization rates. Our findings were carried out in a single geographic region and may not be generalizable to other communities.

Thus, despite improvements in the overall prognosis of patients with AMI over the last 2 decades, new-onset AF remains common and is related to in-hospital and post-discharge adverse outcomes, including higher rates of early hospital readmission. Increased in-hospital monitoring and short-term post-discharge surveillance appears warranted for patients who develop AF in the context of AMI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by the following grants - 1U01HL105268-01 (DDM, JSS), KL2RR031981 (DDM), 1R15HL121761-01A1 (DDM), 4UH3TR000921-03 (DDM), 2R56HL035434-31 (DDM, RJG).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, Singh D, Rienstra M, Benjamin EJ, Gillum RF, Kim YH, McAnulty JH, Jr, Zheng ZJ, Forouzanfar MH, Naghavi M, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray CJ. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014;129:837–847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jabre P, Roger VL, Murad MH, Chamberlain AM, Prokop L, Adnet F, Jouven X. Mortality associated with atrial fibrillation in patients with myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2011;123:1587–1593. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.986661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Wu J, Gore JM. Recent trends in the incidence rates of and death rates from atrial fibrillation complicating initial acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. Am Heart J. 2002;143:519–527. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.120410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saczynski JS, McManus D, Zhou Z, Spencer F, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. Trends in atrial fibrillation complicating acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitt J, Duray G, Gersh BJ, Hohnloser SH. Atrial fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review of the incidence, clinical features and prognostic implications. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1038–1045. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogunsua AA, Shaikh AY, Ahmed M, McManus DD. Atrial Fibrillation and Hypertension: Mechanistic, Epidemiologic, and Treatment Parallels. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal. 2015;11:228–234. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-11-4-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sardar P, Kundu A, Nairooz R, Chatterjee S, Ledley GS, Aronow WS. Health resource variability in the achievement of optimal performance and clinical outcome in ischemic heart disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11886-014-0551-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crenshaw BS, Ward SR, Granger CB, Stebbins AL, Topol EJ, Califf RM. Atrial fibrillation in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: the GUSTO-I experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:406–413. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong CK, White HD, Wilcox RG, Criger DA, Califf RM, Topol EJ, Ohman EM. Significance of atrial fibrillation during acute myocardial infarction, and its current management: insights from the GUSTO-III trial. Card Electrophysiol Rev. 2003;7:201–207. doi: 10.1023/B:CEPR.0000012382.81986.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eldar M, Canetti M, Rotstein Z, Boyko V, Gottlieb S, Kaplinsky E. Significance of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation complicating acute myocardial infarction in the thrombolytic era. SPRINT and Thrombolytic Survey Groups. Circulation. 1998;97:965–970. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Recent changes in attack and survival rates of acute myocardial infarction (1975 through 1981). The Worcester Heart Attack Study. JAMA. 1986;255:2774–2779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM. A two-decades (1975 to 1995) long experience in the incidence, in-hospital and long-term case-fatality rates of acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1533–1539. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Floyd KC, Yarzebski J, Spencer FA, Lessard D, Dalen JE, Alpert JS, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. A 30-year perspective (1975–2005) into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with initial acute myocardial infarction: Worcester Heart Attack Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:88–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.811828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saczynski JS, Spencer FA, Gore JM, Gurwitz JH, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Twenty-year trends in the incidence of stroke complicating acute myocardial infarction: Worcester Heart Attack Study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2104–2110. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spencer FA, Meyer TE, Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Hatton M, Lessard D, Gore JM. Twenty year trends (1975–1995) in the incidence, in hospital and long-term death rates associated with heart failure complicating acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1378–1387. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00390-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg RJ, Samad NA, Yarzebski J, Gurwitz J, Bigelow C, Gore JM. Temporal trends in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1162–1168. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maesen B, Nijs J, Maessen J, Allessie M, Schotten U. Post-operative atrial fibrillation: a maze of mechanisms. Europace. 2012;14:159–174. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta RH, Dabbous OH, Granger CB, Kuznetsova P, Kline-Rogers EM, Anderson FA, Jr, Fox KA, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ, Eagle KA GRACE Investigators. Comparison of outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes with and without atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alasady M, Abhayaratna WP, Leong DP, Lim HS, Abed HS, Brooks AG, Mattchoss S, Roberts-Thomson KC, Worthley MI, Chew DP, Sanders P. Coronary artery disease affecting the atrial branches is an independent determinant of atrial fibrillation after myocardial infarction. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:955–960. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.