Abstract

In spite of wide-spread vaccination, pertussis rates are rising in industrialized countries and remain high world-wide. With no specific therapeutics to treat disease, pertussis continues to cause considerable infant morbidity and mortality. The pertussis toxin is a major contributor to disease, responsible for local and systemic effects including leukocytosis and immunosuppression. Here, we humanized two murine monoclonal antibodies that neutralize pertussis toxin and expressed them as human IgG1 molecules with no loss of affinity or in vitro neutralization activity. When administered prophylactically to mice as a binary cocktail, antibody treatment completely mitigated the B. pertussis-induced rise in white blood cell count and decreased bacterial colonization. When administered therapeutically to baboons, antibody-treated but not control animals experienced a blunted rise in white blood cell count and accelerated bacterial clearance rates. These preliminary findings support further investigation into the use of these antibodies to treat human neonatal pertussis in conjunction with antibiotics and supportive care.

Introduction

Despite wide-spread vaccination, pertussis remains a considerable public health concern. In recent decades, infection rates have risen dramatically in industrialized countries reaching a 60-year US high in 2012. This rise appears to be due to a variety of factors including increased surveillance, strain drift, waning immunity after acellular vaccination, and a vaccine-induced Th1/Th2 response instead of the more effective Th1 response induced by whole cell vaccines and infection (1). Worldwide, pertussis remains a major cause of infant death, claiming ~195,000 lives annually (2). Pertussis is of greatest concern for unimmunized infants, as they experience the most severe symptoms, including pneumonia and pulmonary hypertension due to severe leukocytosis (3). In the absence of alternatives, aggressive interventions including leukodepletion and exchange transfusion have been proposed to remove white blood cells (4).

It is generally accepted that, in the long-term, an improved vaccine formulation better able to prevent disease transmission will be required (1, 5, 6). In the meantime, there remains a need for pertussis-specific therapeutics to treat infants with severe disease as antibiotics are only effective in the early stages, typically before diagnosis. Even after bacteria can no longer be cultured, symptoms persist for many weeks, presumably due to residual toxins.

While B. pertussis produces a wide array of toxins and adhesins, several lines of evidence point to the pertussis toxin (PTx) as a critical virulence factor. This AB5 toxin is essential for full bacterial pathogenicity (7), exhibiting local and systemic effects through its enzymatically active A subunit and its receptor binding B subunit. The overall effects of PTx are inhibition of the innate immune response and induction of leukocytosis. Specifically, in mouse models of pertussis infection, the presence of PTx decreases pro-inflammatory chemokine and cytokine production (8), reduces neutrophil recruitment to the lungs, and increases bacterial burden (9). While these effects have not all been demonstrated in human disease, PTx does appear important in primates as well. In vitro, PTx has been shown to have an inhibitory effect on human dendritic cell migration that is predicted to slow their recruitment to secondary lymph nodes and subsequent activation of T-cells (10). In human infants, PTx production positively correlates with the extreme lymphocytosis that can lead to pulmonary hypertension (11). Finally, whereas most acellular vaccines are comprised of PTx in combination with other antigens, Denmark relies on a monocomponent PTx vaccine and reports no increase in symptomatic infection (12).

Accordingly, high anti-PTx antibody levels are considered to correlate with protection (6, 13), and passive immunization with anti-PTx serum has been recognized as a potential therapeutic modality for neonatal pertussis. In the past two decades, two human polyclonal anti-PTx immunoglobulin preparations were tested and showed promise for treating pertussis in newborns (14–16). However, treatment with polyclonal antisera can be problematic due to low and variable neutralizing capacities as well as an unreliable supply. For passive immunization, monoclonal antibodies provide a considerable advantage as they can be selected for high affinity and potent neutralizing abilities. For these reasons, the high titer intravenous immunoglobulin product to treat RSV was replaced with a single neutralizing antibody in 1996.

To treat pertussis, we propose a combination of two anti-PTx monoclonal antibodies selected to achieve high potency and to limit the possibility of allelic variants that could escape neutralization. Among the numerous anti-PTx monoclonal antibodies that have been evaluated over the past three decades, the murine antibodies 1B7 and 11E6 stand out as uniquely protective in mouse models of pertussis infection (17, 18). However, murine antibodies are no longer considered suitable for use in humans due to their immunogenicity. Here we cloned and humanized the murine 1B7 and 11E6 antibodies, produced them as human IgG1 antibodies in CHO cells, and extensively characterized them in vitro. The humanized antibodies were assessed in a murine challenge model using a recent human B. pertussis isolate and compared to the high-titer intravenous immunoglobulin preparation (P-IVIG) used in recent human clinical trials (15). Finally, the antibodies were tested in a newly described baboon model considered highly relevant for the development of pertussis therapeutics (19). Collectively, the data support further animal modeling to assess the potential for passive immunotherapies to mitigate human neonatal pertussis.

Results

Cloning and humanization of murine 1B7 and 11E6 antibodies

As the first step in humanization, the murine 1B7 (m1B7) and 11E6 (m11E6) antibody heavy and light chain variable region genes were cloned via RT-PCR from hybridoma cells using a degenerate primer set and PTx-reactive genes were identified. Next, 3–5 humanized variants of each variable region were generated in silico and the murine and humanized genes cloned into eukaryotic expression vectors encoding human IgG1 heavy or κ light chain constant domains. All pairwise heavy-light chain combinations were expressed by transiently transfected CHO cells and the supernatant used to monitor specific PTx binding activity (Fig. S1). Combinations yielding the highest specific activity were further analyzed after medium-scale expression and protein A purification. From these data, a single lead candidate was selected for each antibody which exhibited similar ELISA profiles as the murine parents and high expression (~5–10 pg/cell/day). Sequences of these variants are notably more human, as monitored by z-score (Table S1) (20).

Hu1B7 and hu11E6 antibodies are biochemically and biophysically similar to their murine predecessors

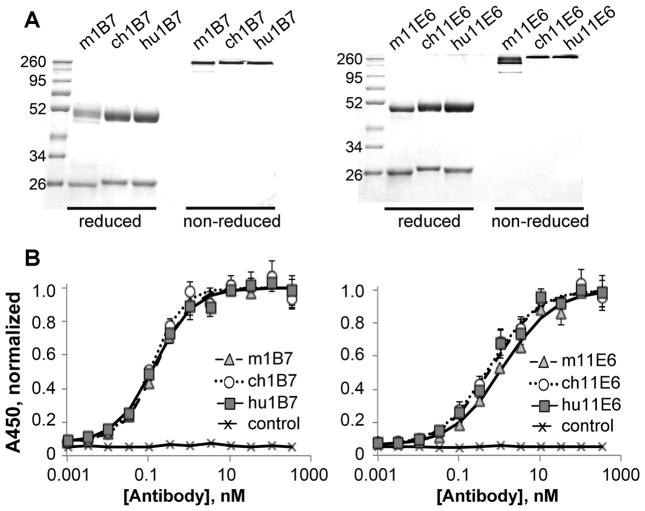

After transient CHO cell expression and purification, the murine (m), chimeric (ch) and humanized (hu) antibodies were pure (~95%) and migrated at the expected sizes in SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 1A). Increased thermal stability was observed, indicating that both the human constant and humanized variable regions are stabilized relative to the murine versions (Table 1, Fig. S2).

Figure 1. Humanized, chimeric and murine antibodies have similar binding affinities to PTx.

A, SDS-PAGE comparing purified murine, chimeric and humanized variants of 1B7 and 11E6 in reduced and non-reduced forms as indicated. Molecular weights standards (kDa) are shown in lane 1. B, Indirect ELISA comparing the binding of all three versions of each antibody to PTx: murine (▲), chimeric (

) and humanized (

) and humanized (

) and isotype control (×) antibodies shown. The absorbance data was normalized such that the maximum signal is 1.0; each sample was run in duplicate and each assay performed at least three times with different protein preparations.

) and isotype control (×) antibodies shown. The absorbance data was normalized such that the maximum signal is 1.0; each sample was run in duplicate and each assay performed at least three times with different protein preparations.

Table 1.

Biochemical characterization of 1B7 and 11E6 antibodies

| Melting temp (°C), second transition | Kd, competition ELISA (nM); (# exp) | Kd, SPR; nM (χ2) | on-rate × 105, SPR (sec−1 M−1) | off-rate × 10−4, SPR (sec−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1B7 | 74.8 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.2 (5) | 0.7 ± 0.2 (0.32) | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| ch1B7 | 78.1 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.3 (3) | 0.5 ± 0.4 (0.74) | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.5 |

| hu1B7 | 79.0 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.7 (6) | 0.7 ± 0.5 (0.75) | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.5 |

| m11E6 | 67.3 ± 0.4 | 5 ± 1 (3) | 2.4 ± 0.9 (2.20) | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 3 ± 3 |

| ch11E6 | 69.4 ± 0.4 | 5 ± 2 (4) | ND* | ND* | ND* |

| hu11E6 | 74.4 ± 0.4 | 7 ± 3 (5) | 2.3 ± 0.7 (1.25) | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.7 |

ND, not determined

Binding to PTx was initially assessed by ELISA (Fig. 1B) and competition ELISA (Fig. S3). The murine and chimeric versions of each antibody, presenting identical variable region amino acid sequences but appended with murine and human constant domains respectively, exhibited very similar binding affinities as measured by competition ELISA (Table 1). We next collected kinetic binding data using surface plasmon resonance with immobilized antibody. The SPR-measured association and dissociation rates were similar for the murine, chimeric and humanized variants, yielding affinities within error for all three 1B7 variants (Kd ~0.7±0.5 nM) and all three 11E6 variants (Kd ~2.3 ± 0.7 nM; Table 1, Fig. S4).

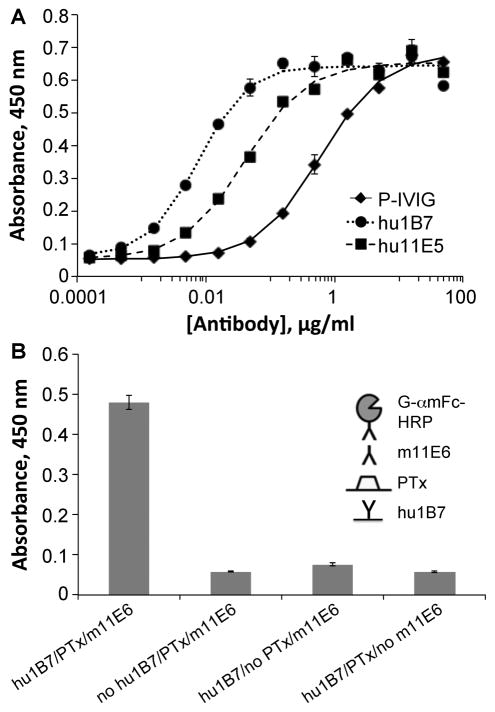

The binary combination of hu1B7 and hu11E6 is synergistic

Not only do hu1B7 and hu11E6 bind PTx tightly, but as monoclonal antibodies, they exhibit ~100-fold and 10-fold higher PTx-specific binding titers, respectively, than the P-IVIG used previously to treat human infants (15) (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, PTx is able to simultaneously bind hu1B7 and m11E6, suggesting their effects may be synergistic (Fig. 2B). Indeed, while either antibody alone protects CHO cells against PTx-mediated morphological changes at ~70:1 (hu1B7) and ~40:1 (hu11E6) molar ratios, an equimolar binary combination exhibits enhanced protection (~20:1; Fig. 3A) which is more neutralizing than an equivalent P-IVIG dose (~120:1; Fig. 3B) (17). Accordingly, a 1:1 molar ratio of hu1B7 and hu11E6 was selected for subsequent animal protection studies.

Figure 2. The hu1B7 and hu11E6 antibodies have higher anti-PTx titers than P-IVIG and can simultaneously bind PTx.

A, Humanized 1B7 and 11E6 antibodies and high-titer P-IVIG were assessed for PTx binding by ELISA. An ELISA plate was coated with PTx, blocked, incubated with the indicated concentrations of P-IVIG (◆), hu1B7 (∘), or hu11E6 (■). B, Sandwich ELISA to assess simultaneous binding of 1B7 and 11E6. Each sample was run in duplicate and each assay repeated at least three times.

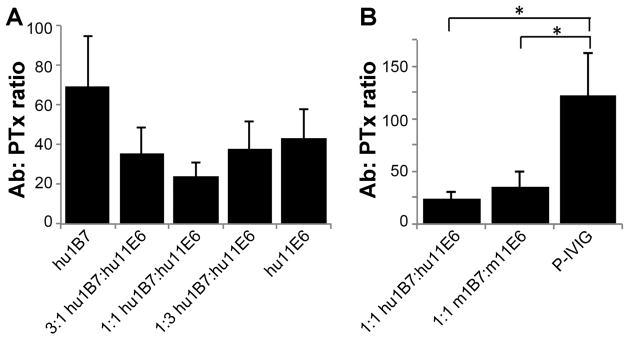

Figure 3. The binary combination of hu1B7 and hu11E6 is synergistic and more potent than P-IVIG in vitro.

The CHO cell clustering assay was used to determine the molar ratio of antibodies to PTx required for complete neutralization of CHO morphology changes. A, Different ratios of hu1B7 and hu11E6 were compared to determine the most potent ratio. B, An equimolar ratio of humanized 1B7 and 11E6 was compared to the same ratio of murine antibodies and P-IVIG. Results depict average of three replicate experiments; statistical significance determined by single-factor ANOVA and Tukey’s test with a=0.05.

Hu1B7 and hu11E6 protect mice prophylactically from B. pertussis infection

While not a natural host for B. pertussis, mouse models share some characteristics of human disease and were used to develop all vaccines to date. In particular, the rate of bacterial clearance in immunized mice after aerosol challenge correlates with vaccine efficacy in children (21). Previously, the Sato group performed murine protection studies with m1B7 and m11E6 using intracerebral and inhalation models with B. pertussis strain 18–323 (17, 18). Since this study was preparatory for non-human primate studies, we replaced strain 18–323, which infects mice efficiently but is a hyper-virulent strain of atypical B. pertussis lineage, with strain D420, a recent human clinical isolate used to develop the baboon model and which expresses the dominant alleles of major virulence factors (22). Pilot studies determined that prophylaxis with 5 μg m1B7 antibody followed by infection with 5×106 cfu D420 resulted in statistically significant differences in WBC, bacterial colonization and weight gain over a 10-day period with groups of six animals (Fig. S5).

Recognizing that antibodies with human constant domains will be cleared from the blood more rapidly than murine antibodies, we assessed the murine in vivo clearance rates of the humanized antibodies for comparison to previously measured m1B7 rates. Mice were administered chimeric or humanized antibodies or a binary cocktail of humanized antibodies (2 mg/kg subcutaneously), and sera were collected over 14 days with anti-PTx concentrations measured by ELISA. The beta elimination half-lives of ~100 hrs for humanized and chimeric antibodies with human constant domains were similar, and, as expected, shorter than that for m1B7 (~210 hrs) (23). We used these data to estimate that a 20 μg dose of humanized antibodies would result in similar serum concentrations on day 10 as the 5 μg m1B7 dose used in pilot studies.

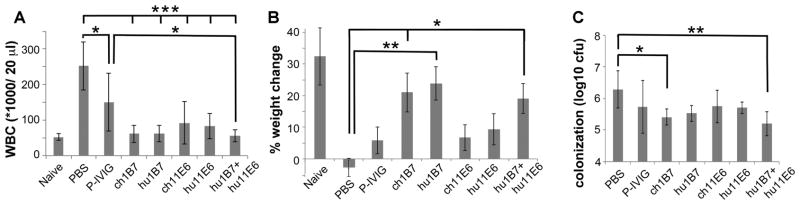

Accordingly, weanling mice were administered 20 μg each of a single humanized or chimeric antibody, P-IVIG, the binary humanized antibody mixture or a PBS control (n=6 per group) before inoculation with 5×106 cfu B. pertussis strain D420. At ten days post-inoculation, untreated mice exhibited ~five-fold increase in WBC relative to naïve mice (Fig. 4A; Table S3), lost weight (Fig. 4B) and were heavily colonized by B. pertussis (Fig. 4C). In contrast, all mice receiving monoclonal antibodies exhibited significantly decreased WBC levels as compared to PBS-treated mice (p<0.001; Fig. 4A). Animals receiving the 1B7 antibody resembled uninfected mice more closely than those receiving only 11E6 or P-IVIG for all outcomes. This was most pronounced in terms of weight gain, as mice receiving ch1B7, hu1B7 or the antibody mixture gained significantly more weight than PBS-treated animals (p<0.05; Fig. 4B). Mice treated with the antibody cocktail were indistinguishable from naïve animals in terms of WBC and weight gain and had significantly lower WBC than P-IVIG-treated mice (p<0.05, Fig. 4A). Finally, mice treated with the binary antibody cocktail had a ~10-fold reduced bacterial colonization levels as compared to untreated mice (p<0.01, Fig. 4C), similar to the reduced colonization observed for PTx-deletion strains (24). P-IVIG was previously tested in human clinical trials (15, 16) with promising initial outcomes; if the correlation between performance in the mouse model holds for human outcomes, this humanized antibody combination could be more protective than P-IVIG.

Figure 4. Prophylactic treatment with humanized antibodies protects mice against pertussis.

Mice (n=6) were each administered 20 μg antibody intraperitoneally two hours before infection with 5×106 cfu B. pertussis D420 bacteria. The infection severity was assessed on day 10 by A, CD45+ leukocyte count (WBC), B, weight gain and C, bacterial colonization of the lungs. No bacteria were recovered from uninfected animals. Means ± standard error are shown; significance * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 and *** p< 0.001 versus PBS-treatment is indicated, using Tukey’s simultaneous test. Additionally, only P-IVIG-treated mice had WBC distinguishable from uninfected naïve mice (p<0.01) and mice treated with hu1B7, ch1B7 or the antibody cocktail had lower WBC than P-IVIG-treatment for equivalent doses (p<0.05). Only mice treated with P-IVIG and ch11E6 exhibited reduced weight gain relative to uninfected mice (p<0.05).

Hu1B7 and hu11E6 protect baboons therapeutically from infection by B. pertussis

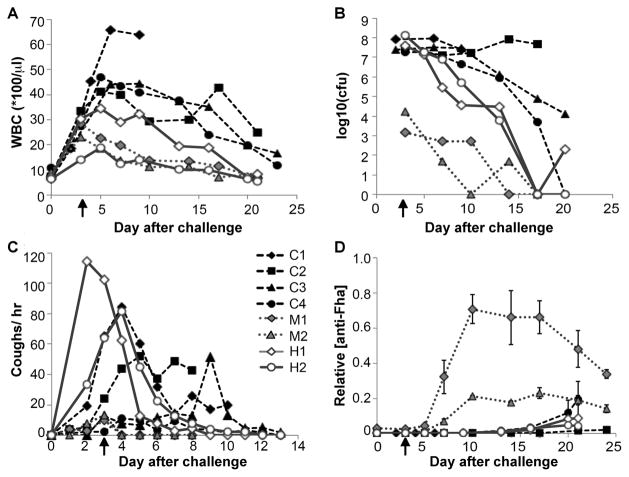

Finally, we used a recently developed nonhuman primate model to assess the feasibility of our antibody cocktail to treat established disease. In this model, bacteria are administered intranasally and intratracheally to weanling baboons, who then exhibit symptoms of classical pertussis including colonization of the trachea, increased WBC counts, and a characteristic cough. No other clinical changes have been associated with disease (19). B. pertussis strain D420 was administered to eight weanling animals on Day 0. Three days later, when the WBC had begun to rise (>14,000/μl; Table S2), the humanized antibody cocktail (20 mg/kg each antibody) was administered intravenously to four of the animals. All eight animals were then monitored for WBC, cough and bacterial colonization (Table S4).

Disease in the untreated animals (n=4) was typical of the model (19): the WBC rose into the 40,000/μl range by day 5 before beginning to decline, approaching baseline after 23 days (Fig. 5A). These animals were heavily colonized by B. pertussis (107–108 cfu recovered by nasopharyngeal wash on days 3–17) and remained elevated for the duration of the study (Fig. 5B). One control animal (C1) became moribund after exhibiting an extremely high WBC. In contrast to the controls, all four animals receiving antibody treatment exhibited a blunted rise in WBC and accelerated removal of bacteria from the nasopharynx (Fig. 5C). At the time of treatment, two of the treated animals had achieved high levels of nasopharyngeal colonization (107–5×108 cfu; denoted H1 and H2), while the other two treated animals experienced moderate levels of nasal carriage (~104 cfu; denoted M1 and M2). These animals exhibited a sharp decrease in WBC coincident with antibody treatment. The measured antibody beta-phase elimination half-life in the treated baboons was 10±4 days, thus the hu1B7 and hu11E6 levels remained high for the duration of the study (Fig. S6). ELISA detection of PTx-reactive antibodies in nasopharyngeal washes indicated that the administered antibodies were present in the mucosa of treated but not control animals (Fig. S7).

Figure 5. Therapeutic treatment with antibody cocktail reduces leukocytosis and accelerates bacterial clearance in baboons.

Weanling baboons were inoculated with 109–1010 B. pertussis D420 bacteria on Day 0. On day 3 after infection (indicated by arrow), animals in the treatment group (n=4) were administered hu1B7 and hu11E6 antibodies intravenously, while control animals (n=4) were given nothing. All animals were subsequently monitored for A, WBC count, B, bacteria recovered by nasopharyngeal wash and C, coughing on the days indicated. Groups shown include controls (solid black icons, dashed line, C1–C4), treated animals who were mildly colonized (grey icons, dotted black line, M1 and M2), and treated animals which were heavily colonized (hollow icons, solid grey line, H1 and H2). D, Serum anti-Fha titers for individual animals are shown to assess endogenous immune responses. Titers were normalized to the maximum response observed for serum from a historical control baboon, collected three weeks after experimental infection. Serum was not available for animal C3.

In this study, the baboon model exhibited variability in cough severity and clinical progression, as is seen in human pertussis (25). All the animals coughed, but this did not strongly correlate with WBC or bacterial colonization levels. Three of the four controls exhibited substantial coughing (>10 per hour) through day 9, while the two heavily colonized, treated animals experienced heavy bouts of coughing (60+ per hour on day 3) which diminished rapidly after antibody treatment (Fig. 5C; Table S2). All treated animals exhibited reduced cough rates by day 5, which were reduced to <5 per hour by day 9. No other clinical observations (body temperature, weight, activity level; Table S4) were found to correlate with disease and potential variables such as insulin, histamine sensitization and blood chemistry have not been evaluated in this model. Notably, PTx does not appear to be responsible for coughing as B. parapertussis does not express PTx, yet causes a similar cough in humans (25). Thus, we would not expect PTx neutralization to affect the cough except indirectly by protecting the innate immune system and the resulting enhanced bacterial clearance.

Histological examination of moribund control animal C1 noted a normal trachea with dense bronchopneumonia and large abcesses, similar to that seen in post-mortem analyses of infants that died of pertussis (3). B. pertussis was recovered from the trachea and right lung of this animal. Histopathology from recovering control and treated animals showed evidence of abcesses and small consolidations. Thus, the damage that occurred to the lung tissue during the first 72 hours of infection may not have had time to repair, consistent with the long-term sequelae following severe pertussis. Histopathological analyses of treated, mildly colonized animals had some abnormalities (fibroses and consolidations) but were overall much healthier (Fig. S8).

We were interested in why two treated animals were less efficiently colonized. To explore this, we evaluated baseline serum antibody levels recognizing another major Bordetella antigen, filamentous hemagglutinin (Fha) by ELISA (Fig. 5D). Animals with clear pertussis symptoms had no baseline serum Fha titer but exhibited detectable levels by day 20, consistent with a primary immune response (19). Interestingly, the two co-housed animals with low levels of nasal carriage also had relatively high initial anti-Fha titers, which exhibited rapid increases starting on day 6, as expected for a secondary immune response (19). From one of these animals, B. bronchiseptica was recovered in the nasal wash (<100 cfu) in addition to B. pertussis. Therefore, we hypothesize that baboons are subject to B. bronchiseptica infection and that concurrent exposure partially protected these two animals, as does prior B. pertussis infection (5).

Discussion

Before widespread vaccination, a number of blood products and polyclonal immunoglobulins were used to treat human pertussis, some with positive, albeit poorly controlled, results (26). More recent preparations were developed on the presumption that PTx is responsible for the severe symptoms of disease and therefore preparations enriched in anti-PTx antibodies would mitigate the symptoms. However, this clinical strategy is limited by the expectation that only a fraction of PTx-specific antibodies in a polyclonal preparation would be neutralizing. In contrast, the monoclonal antibodies utilized in this study were selected specifically for their capacity to neutralize PTx, individually and synergistically. The initial feasibility data using murine and baboon models reported here support the concept of passive immunotherapy to neutralize PTx’s pathological effects.

Previously, two polyclonal anti-PTx preparations elicited by immunization with inactivated PTx were assessed in controlled trials. One showed a significant, ~3-fold decrease in the number and duration of whoops versus placebo-treated children, an effect which was most pronounced when treatment was initiated within the first seven days (14). A subsequent P-IVIG preparation used for Phase 1/2 trials in infants showed declines in lymphocytosis and paroxysmal coughing by the third day after treatment (15). Unfortunately, Phase 3 trials did not support this initial promise, as the product expired before study enrollment was completed (16). Given the dosage and blood volume of infants enrolled in these studies, both achieved the goal of high and sustained anti-PTx titers but observed variable effects on clinical outcomes.

The murine antibodies 1B7 and 11E6 are each highly protective alone, and the combination was previously shown to function synergistically in aerosol and intracerebral murine models (18). Notably, they were more efficacious than a polyclonal anti-PTx preparation and provided significant protection when administered up to seven days after infection as measured by survival, leukocytosis and bacterial colonization (17). Since 11E6 is thought to competitively inhibit PTx binding to cellular receptors (18), this antibody appears to prevent the initial PTx-cell interaction, but may require a 2:1 stoichiometry for complete neutralization of the two binding sites on each PTx molecule. Unlike 11E6, 1B7 appears to alter PTx intracellular trafficking such that the toxin never reaches its G-coupled protein target (27). Hu1B7 and m11E6 can simultaneously bind PTx (Fig. 2), indicating that the epitopes do not overlap and supporting the hypothesis that hu1B7 and hu11E6 are synergistic by virtue of complementary mechanisms. This notion is further supported by the in vitro CHO cell neutralization data shown here, in which the humanized antibodies displayed synergy when combined in an equimolar ratio (Fig. 3). Based on these data, we think synergy is highly likely, although the murine studies presented here were designed to demonstrate protection conferred by humanized antibodies against a clinically relevant strain as opposed to synergy.

The promising clinical results with P-IVIG and the availability of murine antibodies conferring in vivo protection with complementary mechanisms led us to hypothesize that humanized versions of these antibodies would efficiently block PTx activities and treat pertussis symptoms in humans. The humanized 1B7 and 11E6 antibodies are biochemically similar to the original murine versions, leading to the expectation that they will exhibit similar efficacy. This was initially evaluated in a prophylactic murine aerosol model using a recent human clinical isolate. Not only did the humanized antibodies protect as well as the chimeric antibodies, but the individual antibodies and the binary combination significantly mitigated disease in terms of weight gain, lung colonization and WBC (Fig. 4).

The murine aerosol mouse model was used to develop current acellular vaccines and support their progression to human clinical trials. However, in 2012 a non-human primate model, which may have better predictive value for human disease, was first reported. Using this model, we observed leukocytosis and bacterial colonization in control animals which resolved after three weeks, typical of the model (19). Antibody-treated animals exhibited a blunted WBC rise and accelerated bacterial clearance (Fig. 5), supporting a role for these antibodies to treat pertussis in critically ill infants.

Notably, the baboon model introduces a large number of bacteria (109–1010 CFU) into the respiratory tract, resulting in rapid onset of disease, with WBC elevation apparent in 2–3 days and heavy coughing in 3–4 days. In contrast, humans are likely infected with a smaller inoculum via contact or aerosols, exhibiting comparable clinical symptoms 2–3 weeks after infection (28). This is similar to baboons experimentally infected by contact or aerosol transmission, who showed peak WBC several weeks after infection (29). Together, these data suggest that the baboon clinical symptoms observed on day three correspond to human symptoms several weeks after infection. As there is no prior data evaluating pertussis therapeutics in baboons, treatment on day three post-infection was selected due to the rapid onset of disease in baboons, the expected antibody serum half-life, and the appearance of endogenous baboon antibody responses as early as 12-days post-infection. Additional animal modeling and human clinical trials would determine the windows during which antibody treatment could affect disease outcomes.

Interestingly, the two baboons that were only mildly colonized with B. pertussis were likely partially protected through concurrent exposure to B. bronchiseptica. This organism is endemic in many animal populations but has not been described in baboons (25). Here, two co-housed animals were mildly colonized by B. pertussis (103 –104 cfus recovered), with similar day 3 WBC and coughing as all other animals; symptoms which resolved rapidly upon antibody administration (Table S2). Protection against B. pertussis infection has been observed for mice previously infected with B. bronchiseptica (30); concurrent exposure in baboons may also provide some cross-protection. An important implication is that baboons must be protected from and monitored for B. bronchiseptica exposure prior to use in B. pertussis studies.

By immediately arresting PTx activities, the hu1B7/hu11E6 antibody cocktail appears to have two effects on disease progression, as observed in both the murine and baboon models. First, since PTx is directly responsible for the elevated WBC, blocking this activity prevents further leukocytosis, protecting against pulmonary hypertension and organ failure, the specific causes of infant death from pertussis. Second, by modifying Gi/o proteins, PTx interferes with innate immune responses; in particular, chemotaxis to the lungs and subsequent oxidative burst (8, 9). Antibody-mediated blockade of these activities is expected to allow neutrophils and macrophages to more efficiently phagocytose B. pertussis, thereby resolving the pertussis infection and preventing secondary infections. As there is no evidence to support direct antibacterial effects mediated by these antibodies, protection of the innate immune system would explain the ~10-fold reduction in bacterial colonization levels observed in mice (Fig. 4) and baboons (Fig. 5) after antibody treatment. These results are consistent with studies showing similar reductions in murine colonization by PTx-deficient B. pertussis and B. parapertussis strains (7, 24, 31) and the inability of acellular vaccination to prevent subsequent bacterial colonization of mice or baboons (5, 32). While the bacteria localize in the lungs, the various murine responses to PTx, including hyper-insulinemia and histamine sensitization, suggest the toxin is widely distributed and thus antibodies are likely required systemically to neutralize PTx activities.

Two potential challenges for an antibody therapeutic to treat pertussis are maternal vaccination and early identification of exposed or high-risk infants. Currently, maternal vaccination is the leading strategy in development to protect newborns from pertussis prior to initiation of standard vaccination schedules at two months of age. The goal is to induce high levels of maternal anti-pertussis antibodies for transfer to the fetus in utero that then confer protection after birth. While maternal vaccination is attractive for many reasons, recent uptake data in the US indicate that with optimal healthcare access, 40% of newborns remain unprotected (33), while 86% of pregnancies covered by Medicare did not receive the vaccine (34). Moreover, the resulting infant anti-pertussis titers can be modest at birth and decay rapidly (35). This will leave many infants unprotected and the need for a therapeutic in urgent situations will remain. The neutralizing antibodies described here could provide a complementary therapeutic strategy when maternal immunization fails. Similarly, therapeutic use of anti-pertussis antibodies will require accurate and timely identification of high-risk cases such that the therapy can be administered when it is most effective. We expect minimal interference with subsequent vaccination since only two of the many epitopes included in the vaccine would be masked by hu1B7 and hu11E6.

We believe these data in aggregate support continued development of the humanized 1B7 and 11E6 antibodies toward clinical application. To this end, we are currently planning experiments in neonatal baboons as these appear to better mimic severe pertussis observed in human neonates (36). While these antibodies have affinities typical of those generated by in vivo somatic hypermutation and similar to approved antibody therapeutics, enhanced efficacy may be attained through additional protein engineering efforts to increase the binding affinity (37) or the circulating half-life (38). The evidence presented here and in prior literature suggest that neutralizing PTx will improve recovery when added to the current standard of care, however this notion would need to be clearly demonstrated in controlled human trials with quantitative endpoints prior to broad antibody use. In addition, given the decreasing cost of goods for antibodies and support from non-governmental organizations, the antibodies may be able to prevent disease in the developing world where infants are most likely to die from pertussis. Finally, these results support the notion that PTx is a major protective antigen and should continue to be a focus of future pertussis vaccines.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The objective of this study was to assess the protection conferred by two humanized anti-pertussis toxin antibodies in animal models of pertussis. In both the mouse and baboon model, strain D420, a recent clinical isolate of B. pertussis, was used to infect the animals.

An established murine model used to develop the current vaccine was employed to evaluate the prophylactic protection conferred by these antibodies (17). BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were used for the pharmacokinetic analysis and pertussis challenge, respectively. Based on pilot studies, groups of 6 mice were expected to detect antibodies with 75% of expected activity with 80% confidence in a one-tailed test with p=0.05 (Fig. S5). Mouse studies were terminated at day 10, based on pilot studies showing large differences in outcome at this time.

A weanling baboon model was recently developed that may be more representative of human disease progression as evidenced by colonization of the trachea, WBC rise and paroxysmal coughing (19). This model was used to assess protection conferred by these antibodies when administered therapeutically on day 3 after infection, with four control animals and four treated animals. One control baboon became moribund, and data was not available after day 10 for that animal. Baboons were randomly assigned to groups and animal caretakers and laboratory technicians were blinded. The baboon study was terminated after ~21 days, or when WBC and bacterial colonization levels began to approach pre-infection levels.

Antibody variable region cloning and humanization

The murine 1B7 and 11E6 variable region genes (17) were amplified from hybridoma cells by RT-PCR using degenerate primers and cloned into pAK100 as described (39). Positive clones were identified by monoclonal phage ELISA using a PTx coated plate (1 μg/ml in PBS; List Labs), followed by sequencing. Humanized variants were designed in silico via five different methods: (a) ‘veneering’ (ven); (b) ‘grafting of abbreviated complementarity determining regions (CDRs)’ (abb); (c) ‘specificity determining residue-transfer’ (sdr); and (d) grafting of intact CDRs onto the hu4D5 framework or (e) a composite framework (fra) (27, 40). The resulting designed variable region genes were synthesized with human IgG1/kappa constant domains by DNA 2.0 in pJ602 or pJ607 vectors. For chimeric constructs, murine variable regions were similarly cloned with human constant regions (39).

Protein expression & purification

For small-scale expression, plasmid DNA was transiently transfected into CHO-K1 cells (ATCC) and purified using protein A affinity chromatography as described (39). Large scale preps were prepared by Catalent (Somerset, NJ) from polyclonal CHO cell lines, followed by protein A and anion chromatographic steps and buffer exchange into PBS. P-IVIG was obtained from the Massachusetts Public Health Biologic Laboratory (Lot IVPIG-2). P-IVIG was prepared as a 4% IgG solution from the pooled plasma from donors immunized with tetra-nitromethane inactivated pertussis toxoid vaccine (16).

ELISA and binding assays

For indirect PTx ELISAs, a high-binding 96-well ELISA plate (Costar) was coated with 1 μg/ml PTx. The plate was blocked with milk for 1 hr, followed by incubation with duplicate anti-PTx antibody dilutions from 50 μg/ml for 1 hr at 25 °C. After washing and detection with 50 μl of 1 μg/ml goat anti-mouse-Fc-HRP (murine antibodies, Thermo Fisher), goat-anti-human Fc-HRP (chimeric and human antibodies, Thermo Fisher) or goat-anti-monkey IgG (H/L)-HRP (baboon serum; Bio-Rad), signal was developed with TMB Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific), quenched with 1M HCl and the absorbance at 450 nM recorded. To monitor antibody concentrations in cell culture supernatant, an Fc capture ELISA was employed, using the protocol above with the following modifications: a 5 μg/ml goat-anti-human Fc (Thermo Scientific) coat and 2 μg/ml goat-anti-human kappa-HRP (SouthernBiotech) secondary antibody. For Fha ELISAs with baboon sera, a 1 μg/ml Fha (List) coat and 1:10,000 dilution of goat-anti-monkey IgG (H/L)-HRP (Bio-Rad) secondary antibody was used. Data were scaled to the maximum response observed for positive control serum collected from an animal 3 weeks post-infection.

PTx binding affinity was determined by both competition ELISA and surface plasmon resonance (SPR). For competition ELISA, an ELISA plate was coated with PTx and blocked as described above. While the plate was blocking, 3.25 nM of each antibody in PBS-T-milk was incubated with different concentrations of PTx (200 nM to 0.1 nM). The ELISA plate was washed and 50 μl of the antibody/PTx mixtures added. The plate was incubated for 15 min at 25 °C. The plate was then washed, secondary antibody added and ELISA developed as above. The resulting curves were fit to equilibrium binding equations (41) corrected for bivalent binding.

Surface plasmon resonance analysis was performed using a BIAcore 3000 (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden; 1B7 variants) or Reichert SR7500DC (AMETEK, Berwyn, PA, USA; 11E6 variants) instrument with dextran chips. Antibodies were immobilized using standard EDC/NHS chemistry to a level of 500–1000 response units as described (27). PTx was injected in duplicate at 30 μL/min or 100 μL/min (m1B7, ch1B7), with concentrations between 5–200nM diluted in running buffer (PBS or HBS, pH 7.4, 0.05% Tween). The surface was regenerated with a combination of 4M magnesium chloride and 10mM glycine, optimized independently for each antibody. Baseline correction was performed by subtracting simultaneous runs over an in-line control flow cell. The on- and off-rates were calculated using BIAevaluation software (Pharmacia Biosensor) or TraceDrawer (Reichert). Reported values are the average and standard deviation of all on- and off- rates calculated for each protein.

In vitro neutralization

Inhibition of CHO cell clustering was used to determine in vitro neutralization of antibody preparations as described (27). Briefly, antibody was serially diluted across a 96-well tissue plate from 50 nM to 1.5 pM in the presence of 5 pM PTx. Antibody and PTx were incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C after which 2×104 freshly trypsinized CHO cells were added per well. After incubation at 37 °C for 20 hours, the degree of clustering was scored as 0 (no clustering), 1 (equivocal), 2 (positive clustering), or 3 (maximal clustering). Experiments were performed in triplicate and scored independently by two researchers. Neutralizing dose is expressed as the molar ratio of antibody:PTx resulting in a score of 2.

Bacterial strain and growth

B. pertussis strain D420 was isolated from a critically ill infant in Texas in 2002 (22). Bacteria were maintained on Regan-Lowe Agar (Becton Dickinson) supplemented with 10% sheep’s blood (Hemostat) with 20 μg/mL cephalexin. Liquid cultures were grown overnight in Stainer-Schölte broth with heptakis at 37 °C to mid-log phase.

Ethics Statement

All animal procedures were performed in a facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International in accordance with protocols approved by UT Austin (#2012-00084, #13080701), PSU (#40029) and the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (#14-072-I) Animal Care and Use Committee and the principles outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Murine pharmacokinetic assay

An in vivo pharmacokinetic study was completed using groups of six ~12 weeks old female BALB/c mice as described previously (23). Chimeric 11E6, humanized 11E6, humanized 1B7, or a 1:1 mixture of the humanized 1B7 and 11E6 antibodies at the same total antibody concentration were diluted to 250 μg/ml in PBS and 200 μl injected subcutaneously. Blood samples were collected via the tail vein at seven time points between 0 to 336 hours. Antibody concentration in sera was measured by PTx ELISA. After the final time point, mice were euthanized via CO2 inhalation and cervical dislocation. To estimate the beta half-life, the data was fit to a single exponential decay model: C(t) = bexp(−βt)

In vivo mouse challenge

Groups of six randomly assigned weanling C57BL/6 mice were each injected intraperitoneally with a single antibody (20 μg), P-IVIG (20 μg), or the antibody combination (10 μg hu1B7+10 μg hu11E6), or PBS two hours before sedation with 5% isofluorane in oxygen and inoculation with 5×106 CFU B. pertussis strain D420 in PBS by pipetting 50 μL on the external nares. Investigators were not blinded. The % weight change was calculated by the following formula: ((day 10 weight − day 0 weight/day 0 weight)*100) for each individual mouse. On day 10 mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and the respiratory tract was excised for enumeration by serial plating on Regan Lowe agar supplemented with 10% sheep’s blood (Hemostat Resources) containing 40 ug/mL cephalexin. Colonies were counted after 5 days at 37°C.

To assess the number of CD45+ white blood cells, blood was collected by orbital bleed (day 10) in a microtainer containing EDTA (Becton, Dickinson, and Company), and 50 μL blood were lysed in 4 mL red blood cell lysis solution (Alfa Aesar) for 6 minutes. Cells were incubated with anti-CD45 APC, washed, and resuspended in 2% paraformaldehyde before acquisition on the LSR Fortessa flow Cytometer (Becton, Dickinson, and Company). List mode data was then analyzed on FlowJo 7.6.1 (Treestar), with data reported as total WBC per 40 ul blood.

Baboon challenge study

Baboon studies were performed at the Oklahoma Baboon Research Resource at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center as described previously (19). Weanling baboons were selected to be 6–9 months old at the time of challenge. Groups consisted of four animals based on published vaccination studies (19). The inoculum for each direct challenge was between 109–1010 cfu as determined by optical density and confirmed by serial dilution and plating. The bacterial inoculum (1 ml) was delivered on day 0 via intranasal and intratracheal infusion. On day 3 after infection, animals were sedated and humanized anti-pertussis toxin antibodies administered intravenously (20 mg/kg each). Post challenge, baboons were anesthetized and evaluated twice weekly for enumeration of circulating WBC, serum antibody levels, and nasopharyngeal bacterial load. Nasopharyngeal washes were diluted and plated on Regan–Lowe plates to quantify bacterial cell counts. Video recordings of each cage allowed quantification of cough rates. Sera were assessed for antibody titers to Bordetella antigens Fha and PTx by ELISA. At the end of the study, baboons were euthanized with an intravenous injection of euthanasia solution and necropsy was performed. Tissues were embedded and stained with H&E and evaluated by a veterinary pathologist.

Statistical Analysis

Mean ± error values were determined for all appropriate data. For the murine challenge experiment, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s simultaneous test with significance (p <0.05) was used to determine statistical significance between groups. Error bars reported in mouse, baboon, and CHO cell assay experiments represent the standard error. All other error reported is the standard deviation.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Specific activity of humanized antibody variants.

Fig. S2. Antibody thermal stability.

Fig. S3. Competition ELISA to assess solution binding affinities of purified antibodies.

Fig. S4. Binding kinetics of antibody-PTx interaction.

Fig. S5. Pilot murine protection data with recent human clinical isolate D420 and murine 1B7.

Fig. S6. Concentrations of anti-PTx antibodies in baboons.

Fig. S7. Detection of the hu1B7/hu11E6 combination in the nasopharyngeal wash of baboons.

Fig. S8. Histopathological analysis of lung tissue.

Table S1. Humanized antibodies are more similar to the human repertoire than the original murine antibodies.

Table S2. Baboon model challenge details.

Table S3. Tabulated mouse challenge data.

Table S4. Tabulated baboon challenge data.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jerry Keith, NIH for the 1B7 and 11E6 hybridomas; Donna Ambrosino, Mass Biologics for P-IVIG; Tod Merkel, FDA for helpful discussions and Hiroko and Yuji Sato for their publications on the murine 1B7 and 11E6 antibodies.

Funding: We acknowledge the following funding sources: NIH AI066239, Norm Hackerman Advanced Research Project #003658-0019-2011, Welch F-1767 and Synthetic Biologics (JAM); NIH P40OD010431 and P40OD010988 (RFW).

Footnotes

Author contributions: A.W.N., E.K.W. and J.A.M. planned, performed, and analyzed antibody humanization, antibody characterization and baboon antibody detection experiments. J.R.L. planned, performed, and analyzed mouse pharmacokinetic experiments. E.A.P., A.W.N., E.K.W. and A.B. designed the humanized antibody sequences. J.A.M., E.T.H., L.G. and W.E.S. planned, performed, and analyzed mouse challenge experiments. J.A.M., M.K., J.F.P. and R.F.W. designed, planned, performed, and analyzed baboon challenge experiments. M.K. and J.A.M. supervised and designed experiments. J.A.M. wrote the first manuscript draft and all authors contributed to manuscript revision.

Data and materials availability: hu1B7 and hu11E6 antibodies are available upon request.

Competing interests: M.K. and A.B. are employed by Synthetic Biologics, which has a financial interest in hu1B7 and hu11E6. J.A.M., A.W.N., E.K.W., and E.A.P. have filed a provisional patent jointly with Synthetic Biologics with the US Patent and Trademark Office for humanized pertussis antibodies. This work was supported in part by funding from Synthetic Biologics.

References

- 1.Cherry JD. Pertussis: challenges today and for the future. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003418. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Bassani DG, Jha P, Campbell H, Walker CF, Cibulskis R, Eisele T, Liu L, Mathers C W. H. O. Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of, Unicef, Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1969–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paddock CD, Sanden GN, Cherry JD, Gal AA, Langston C, Tatti KM, Wu KH, Goldsmith CS, Greer PW, Montague JL, Eliason MT, Holman RC, Guarner J, Shieh WJ, Zaki SR. Pathology and pathogenesis of fatal Bordetella pertussis infection in infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:328–338. doi: 10.1086/589753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nieves D, Bradley JS, Gargas J, Mason WH, Lehman D, Lehman SM, Murray EL, Harriman K, Cherry JD. Exchange blood transfusion in the management of severe pertussis in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:698–699. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31828c3bb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warfel JM, Zimmerman LI, Merkel TJ. Acellular pertussis vaccines protect against disease but fail to prevent infection and transmission in a nonhuman primate model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:787–792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314688110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robbins JB, Schneerson R, Keith JM, Miller MA, Kubler-Kielb J, Trollfors B. Pertussis vaccine: a critique. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:237–241. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31818a8958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss AA, Hewlett EL, Myers GA, Falkow S. Pertussis toxin and extracytoplasmic adenylate cyclase as virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:219–222. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreasen C, Carbonetti NH. Pertussis toxin inhibits early chemokine production to delay neutrophil recruitment in response to Bordetella pertussis respiratory tract infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5139–5148. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00895-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirimanjeswara GS, Agosto LM, Kennett MJ, Bjornstad ON, Harvill ET. Pertussis toxin inhibits neutrophil recruitment to delay antibody-mediated clearance of Bordetella pertussis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3594–3601. doi: 10.1172/JCI24609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fedele G, Bianco M, Debrie AS, Locht C, Ausiello CM. Attenuated Bordetella pertussis vaccine candidate BPZE1 promotes human dendritic cell CCL21-induced migration and drives a Th1/Th17 response. J Immunol. 2011;186:5388–5396. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mu HH, Cooley MA, Sewell WA. Studies on the lymphocytosis induced by pertussis toxin. Immunol Cell Biol. 1994;72:267–270. doi: 10.1038/icb.1994.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thierry-Carstensen B, Dalby T, Stevner MA, Robbins JB, Schneerson R, Trollfors B. Experience with monocomponent acellular pertussis combination vaccines for infants, children, adolescents and adults--a review of safety, immunogenicity, efficacy and effectiveness studies and 15 years of field experience. Vaccine. 2013;31:5178–5191. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storsaeter J, Hallander HO, Gustafsson L, Olin P. Low levels of antipertussis antibodies plus lack of history of pertussis correlate with susceptibility after household exposure to Bordetella pertussis. Vaccine. 2003;21:3542–3549. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granstrom M, Olinder-Nielsen AM, Holmblad P, Mark A, Hanngren K. Specific immunoglobulin for treatment of whooping cough. Lancet. 1991;338:1230–1233. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruss JB, Malley R, Halperin S, Dobson S, Dhalla M, McIver J, Siber GR. Treatment of severe pertussis: a study of the safety and pharmacology of intravenous pertussis immunoglobulin. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:505–511. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199906000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halperin SA, Vaudry W, Boucher FD, Mackintosh K, Waggener TB, Smith B. Is pertussis immune globulin efficacious for the treatment of hospitalized infants with pertussis? No answer yet. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:79–81. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000247103.01075.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato H, Sato Y. Protective activities in mice of monoclonal antibodies against pertussis toxin. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3369–3374. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3369-3374.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato H, Sato Y, Ito A, Ohishi I. Effect of monoclonal antibody to pertussis toxin on toxin activity. Infect Immun. 1987;55:909–915. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.4.909-915.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warfel JM, Beren J, Kelly VK, Lee G, Merkel TJ. Nonhuman primate model of pertussis. Infect Immun. 2012;80:1530–1536. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06310-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abhinandan KR, Martin AC. Analyzing the “degree of humanness” of antibody sequences. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:852–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills KH, Ryan M, Ryan E, Mahon BP. A murine model in which protection correlates with pertussis vaccine efficacy in children reveals complementary roles for humoral and cell-mediated immunity in protection against Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:594–602. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.594-602.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boinett CJ, Harris SR, Langridge GC, Trainor EA, Merkel TJ, Parkhill J. Complete Genome Sequence of Bordetella pertussis D420. Genome announcements. 2015;3 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00657-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller MA, Khan TA, Kaczorowski KJ, Wilson BK, Dinin AK, Borwankar AU, Rodrigues MA, Truskett TM, Johnston KP, Maynard JA. Antibody nanoparticle dispersions formed with mixtures of crowding molecules retain activity and in vivo bioavailability. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101:3763–3778. doi: 10.1002/jps.23256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carbonetti NH, Artamonova GV, Mays RM, Worthington ZE. Pertussis toxin plays an early role in respiratory tract colonization by Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6358–6366. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6358-6366.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattoo S, Cherry JD. Molecular pathogenesis, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations of respiratory infections due to Bordetella pertussis and other Bordetella subspecies. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:326–382. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.326-382.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGuinness AC, Bradford WL, Armstrong JG. The production and use of hyperimmune human whooping cough serum. J Pediatrics. 1940;16:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutherland JN, Maynard JA. Characterization of a key neutralizing epitope on pertussis toxin recognized by the monoclonal antibody 1B7. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11982–11993. doi: 10.1021/bi901532z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonald H, MacDonald EJ. Experimental pertussis. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1933;53:328–330. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warfel JM, Beren J, Merkel TJ. Airborne transmission of Bordetella pertussis. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:902–906. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goebel EM, Zhang X, Harvill ET. Bordetella pertussis infection or vaccination substantially protects mice against B. bronchiseptica infection. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alonso S, Pethe K, Mielcarek N, Raze D, Locht C. Role of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity of pertussis toxin in toxin-adhesin redundancy with filamentous hemagglutinin during Bordetella pertussis infection. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6038–6043. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6038-6043.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smallridge WE, Rolin OY, Jacobs NT, Harvill ET. Different effects of whole-cell and acellular vaccines on Bordetella transmission. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1981–1988. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Healy CM, Ng N, Taylor RS, Rench MA, Swaim LS. Tetanus and diphtheria toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine uptake during pregnancy in a metropolitan tertiary care center. Vaccine. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Housey M, Zhang F, Miller C, Lyon-Callo S, McFadden J, Garcia E, Potter R C. Centers for Disease, Prevention. Vaccination with tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine of pregnant women enrolled in Medicaid--Michigan, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:839–842. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abu Raya B, Srugo I, Kessel A, Peterman M, Bader D, Gonen R, Bamberger E. The effect of timing of maternal tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) immunization during pregnancy on newborn pertussis antibody levels - a prospective study. Vaccine. 2014;32:5787–5793. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warfel JM, Papin JF, Wolf RF, Zimmerman LI, Merkel TJ. Maternal and Neonatal Vaccination Protects Newborn Baboons From Pertussis Infection. J Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maynard JA, Maassen CBM, Leppla SH, Brasky K, Patterson JL, Iverson BL, Georgiou G. Protection against anthrax toxin by recombinant antibody fragments correlates with antigen affinity. Nature Biotechnology. 2002;20:597–601. doi: 10.1038/nbt0602-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robbie GJ, Criste R, Dall’acqua WF, Jensen K, Patel NK, Losonsky GA, Griffin MP. A novel investigational Fc-modified humanized monoclonal antibody, motavizumab-YTE, has an extended half-life in healthy adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:6147–6153. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01285-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, Gray MC, Hewlett EL, Maynard JA. The Bordetella adenylate cyclase repeat-in-toxin (RTX) domain is immunodominant and elicits neutralizing antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:3576–3591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.585281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishida M, Uematsu N, Kobayashi H, Matsunaga Y, Ishida S, Takata M, Niwa O, Padlan EA, Newman R. BM-ca is a newly defined type I/II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody with unique biological properties. International journal of oncology. 2011;38:335–344. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2010.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martineau P. In: Antibody Engineering. Dübel RKaS., editor. Vol. 1. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2010. chap. 41. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Specific activity of humanized antibody variants.

Fig. S2. Antibody thermal stability.

Fig. S3. Competition ELISA to assess solution binding affinities of purified antibodies.

Fig. S4. Binding kinetics of antibody-PTx interaction.

Fig. S5. Pilot murine protection data with recent human clinical isolate D420 and murine 1B7.

Fig. S6. Concentrations of anti-PTx antibodies in baboons.

Fig. S7. Detection of the hu1B7/hu11E6 combination in the nasopharyngeal wash of baboons.

Fig. S8. Histopathological analysis of lung tissue.

Table S1. Humanized antibodies are more similar to the human repertoire than the original murine antibodies.

Table S2. Baboon model challenge details.

Table S3. Tabulated mouse challenge data.

Table S4. Tabulated baboon challenge data.