Abstract

Achalasia is the most common primary motility disorder of the esophagus and presents as dysphagia to solids and liquids. It is characterized by impaired deglutitive relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. High-resolution manometry allows for definitive diagnosis and classification of achalasia, with type II being the most responsive to therapy. Since no cure for achalasia exists, early diagnosis and treatment of the disease is critical to prevent end-stage disease. The central tenant of diagnosis is to first rule out mechanical obstruction due to stricture or malignancy, which is often accomplished by endoscopic and fluoroscopic examination. Therapeutic options include pneumatic dilation (PD), surgical myotomy, and endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin injection. Heller myotomy and PD are more efficacious than pharmacologic therapies and should be considered first-line treatment options. Per oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) is a minimally-invasive endoscopic therapy that might be as effective as surgical myotomy when performed by a trained and experienced endoscopist, although long-term data are lacking. Overall, therapy should be individualized to each patient’s clinical situation and based upon his or her risk tolerance, operative candidacy, and life expectancy. In instances of therapeutic failure or symptom recurrence re-treatment is possible and can include PD or POEM of the wall opposite the site of prior myotomy. Patients undergoing therapy for achalasia require counseling, as the goal of therapy is to improve swallowing and prevent late manifestations of the disease rather than to restore normal swallowing, which is unfortunately impossible.

Keywords: Per oral endoscopic myotomy, Dilation, Achalasia, Treatment, Endoscopy, Myotomy, Per oral

Core tip: Achalasia can be classified into three subtypes based on high-resolution manometry, with type 2 being the most responsive to therapy. Since no cure for achalasia exists, early diagnosis and treatment of the disease are critical. Pre-treatment counseling is paramount, as the goal of therapy is to improve swallowing and prevent late manifestations of the disease, rather than to restore normal swallowing and function. Pneumatic dilation and surgical or endoscopic myotomy are efficacious and reasonable first-line treatment options in appropriate candidates. In instances of therapeutic failure or symptom recurrence, different treatment modalities might need to be applied.

INTRODUCTION

Achalasia, a disease first described by Sir Thomas Willis in 1674 and formally named by Dr. Hertz in 1915[1], is the most common primary motility disorder of the esophagus. It is characterized by impaired deglutitive relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) due to loss of the myenteric plexus[2]. While the inciting mechanism is not fully understood, autoimmune, viral immune, or neurodegenerative etiologies have been implicated[3]. It has been speculated that achalasia arises from a cascade of neuronal degeneration that is predicated on a viral infection triggering an autoimmune process in a genetically susceptible host[4]. An imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters then leads to unopposed cholinergic stimulation thereby impairing LES relaxation. The disease has an estimated annual incidence of 1.6 in 100000 and a prevalence of 10.8 in 100000, with a peak age range between 30 and 60 years[4]. There is no racial or gender disparity in those with the condition[4].

Achalasia should be suspected in patients experiencing dysphagia to solids and liquids, and it is often accompanied by regurgitation of undigested food and saliva. The predominant symptom of progressive dysphagia to liquids and solids occurs in approximately 90% of patients with achalasia, and 76% to 91% of patients experience the next most common symptom of regurgitation[5-7]. Other symptoms including nocturnal aspiration or cough, heartburn, odynophagia, and epigastric pain occur to a variable extent[7]. Chest pain, seen in 25% to 64% of patients, is predominantly present in type III achalasia and generally responds less well to treatment than other symptoms, such as dysphagia and regurgitation[8].

The symptoms associated with achalasia are non-specific, which can lead to long delays between symptom onset and diagnosis (sometimes taking up to 5 years to make the diagnosis)[9,10]. Similarly, patients without achalasia can also present with symptoms of dysphagia, regurgitation, recurrent aspiration, and chest pain in the setting of prior lap-band surgery, fundoplication, or pseudoachalasia - a syndrome that can involve malignant infiltration of the area encompassing the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). Approximately 2% to 4% of patients suspected of having achalasia suffer from pseudoachalasia, although these patients tend to be older and have a shorter history of symptoms with more prominent weight loss[11]. When pseudoachalasia is suspected, expeditious evaluation for an infiltrative malignancy should be undertaken via endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography or cross-sectional imaging. Certain paraneoplastic syndromes can give rise to pseudoachalasia, and in cases of suspected small-cell lung carcinomas checking for type-1 antineuronal nuclear autoantibody (ANNA-1, also known as “anti-Hu” antibody) can sometimes be diagnostic[12]. Lastly, Chagas disease, which is caused by infection with Trypanosoma cruzi, can also result in achalasia, in addition to diffuse myenteric destruction, that can manifest as megacolon, heart disease, and neurologic disorders[3].

While eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) can present as dysphagia in the absence of mechanical obstruction, achalasia should be easily distinguishable from EoE by endoscopic and manometric findings. Furthermore, if esophageal biopsies are required to exclude EoE as a possible diagnosis, care should be taken to avoid deep or extensive biopsies along the anterior (1 to 2 o’clock) or posterior walls (5 to 7 o’clock) of the mid-to-distal esophagus so as to prevent the formation of submucosal fibrosis, which can make future surgical or endoscopic myotomy more difficult.

DIAGNOSIS

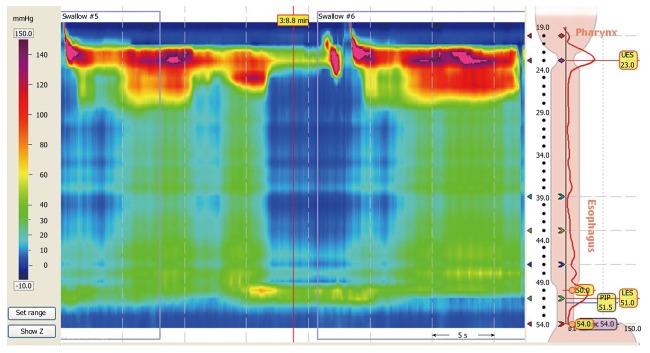

In patients with dysphagia and suspected achalasia, radiographic and endoscopic modalities should be utilized to exclude mechanical causes of dysphagia and to evaluate for GEJ narrowing or hypertonicity and esophageal dilation, which can support the diagnosis of achalasia. It should be noted that in early achalasia, both barium studies and endoscopy may be normal. However, in later stages, barium swallow may be characterized by the classic “bird’s beak” appearance, whereby a dilated esophagus tapers significantly at the GEJ (Figure 1). An associated air-fluid level in the esophagus and an absent gastric bubble are other fluoroscopic clues of possible achalasia. Not only is a barium esophagram important in defining the morphology of the esophagus, but it can also be used as a functional test whereby an upright esophagram can be performed to measure esophageal emptying times over a 5-min period or longer[13,14].

Figure 1.

Barium esophagram of a patient before and several months after per oral endoscopic myotomy. A 45-year-old woman with type II achalasia underwent per oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM). The pre-procedural barium esophagram (A, left panel) demonstrated a dilated esophagus with tapering at the gastroesophageal junction. Following POEM the patient gained 32 lbs over a 9-mo period but had occasional symptoms of regurgitation, which we suspected was from eating too much too quickly. Repeat barium esophagram showed the distal tapering of the gastroesophageal junction has resolved and there was immediate and unimpeded passage contrast passage into the stomach (B, right panel). A distal esophageal diverticulum was incidentally found, which can be seen in patients following POEM with a complete myotomy of the distal esophagus that is carried across the lower esophageal sphincter and into the gastric cardia.

Endoscopy is important in the diagnostic workup of patients with achalasia, as it can rule out luminal malignancies of the esophagus and proximal stomach, which can also cause symptoms of dysphagia and weight loss. On endoscopic evaluation of patients with achalasia, static food and fluid are frequently found in an esophagus that is dilated proximal to the GEJ. Furthermore, a careful endoscopist can also evaluate for increased tone of the LES. In patients with “classic” achalasia, a diagnostic gastroscope can encounter moderate resistance at the LES and GEJ. With steady pressure and advancement of the gastroscope, ultimately the scope will pass into the stomach leading to a sensation of “giving way” or a “pop.” Despite this “resistance” to passage of the gastroscope, achalasia is characterized by the absence of any mass, stricture, or mechanical obstruction. In patients with achalasia, stasis of luminal contents in the esophagus has also been implicated in development of esophagitis and might play a role in the 7-to-140-fold increased risk of subsequent esophageal adenocarcinoma, further supporting the need for endoscopic evaluation and possible screening in these patients[7].

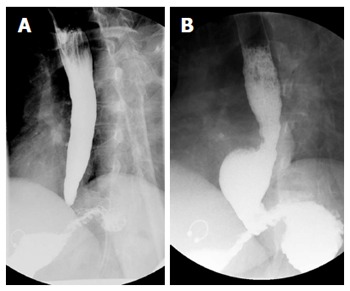

Manometry remains the gold standard for diagnosis of achalasia and offers diagnostic accuracy in greater than 90% of cases[15]. The procedure involves the placement of a flexible pressure catheter through the nose, into the esophagus, and across the GEJ. Prior conventional manometric line tracings have now been supplanted by high-resolution manometry (HRM) that presents pressure data in the context of esophageal-pressure-topography plots[4]. HRM metrics using Clouse plots led the way to the variant descriptions of achalasia subtypes in the Chicago classification system[16-20]. The manometric finding of aperistalsis and incomplete LES relaxation in a patient without mechanical obstruction of the esophagus supports the diagnosis of achalasia in the appropriate clinical situation[3]. On HRM, impaired GEJ relaxation (or incomplete LES relaxation) is characterized by mean 4-second integrated relaxation pressure (IRP) of ≥ 10 to 15 mmHg[21].

SUBTYPES OF ACHALASIA

The Chicago classification is a currently accepted system that separates “classic” achalasia into 3 clinically relevant subtypes[21]. The manometric findings common to all types of achalasia include impaired relaxation of the LES (residual pressure or IRP of ≥ 10 mmHg) and absent peristalsis in a patient without mechanical obstruction near the LES[3,18-20]. The variant types of achalasia are further defined as follows[21]: Type I: has 100% absent peristalsis and no significant esophageal pressurization; Type II: has 100% absent peristalsis with ≥ 20% of swallows with pan-esophageal pressurization to > 30 mmHg (Figure 2); Type III: has ≥ 20% of swallows with premature spastic contractions (distal latency of < 4.5 s).

Figure 2.

High-resolution esophageal manometry of a patient with achalasia. A 34-year-old man with progressive dysphagia to liquids and solids had a barium esophagram suggestive of achalasia. He presented for high-resolution manometry to confirm the diagnosis of achalasia. The manometric and topographic findings demonstrated aperistalsis with residual pressure at the lower esophageal sphincter with an elevated integrated relaxation pressure and pan-esophageal pressurization, which was consistent with type II achalasia by the Chicago classification.

These classifications are not only descriptive, but they also have useful prognostic and therapeutic implications. Patients with type II achalasia have the best prognosis with 96% of patients reporting symptomatic improvement following treatment with myotomy or pneumatic dilation (PD). Patients with type I achalasia have response rates of around 81%, as these patients probably have late-stage disease with complete loss of inhibitory neurons. Patients with type III achalasia have the worst treatment response, estimated at around 66%, and this entity might actually represent a distinct entity unrelated to loss of inhibitory neurons[8,21].

TREATMENT

Early diagnosis to prevent end-stage disease should be the primary goal in the management of achalasia, as no curative therapies exist for this problem. Two percent to five percent of patients with achalasia will develop manifestations of end-stage disease, characterized by massive dilation and a sigmoid-like appearance of the esophagus - the so-called “mega-esophagus,” which can necessitate esophagectomy[22]. Encouragingly, various treatments are available to alleviate dysphagia, restore lost weight, and combat progression to later-stage disease. Traditional therapeutic options have included surgical myotomy, PD, and pharmacologic therapy. However, novel, less-invasive, endoscopic myotomy techniques have also been demonstrated to be efficacious in expert centers. These therapies, which should be individualized to each patient’s symptoms, age, and co-morbidities, are primarily aimed at disrupting the dysfunctional deep muscle of the distal esophageal and LES in order to permit the passive passage of food.

When considering an interventional procedure, it is also important to determine how clinical response can be gauged. In the case of treating achalasia, in addition to pre- and post-intervention barium and manometric studies, the Eckardt score offers a quantitative way to assess the clinical symptomatology of patients before and after achalasia therapy[23,24].

Heller myotomy

Surgical myotomy was first performed and described by Heller in 1914 as a trans-abdominal extramucosal cardioplasty performed onto the anterior and posterior walls of the cardia[1]. The procedure was widely adopted due to its success. In 1962, Dor proposed the “technique de Heller-Nissen modifée” for the treatment of reflux esophagitis associated with cardiospasm, thereby providing relief of dysphagia while limiting gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)[1]. When performed, a concomitant Dor procedure is preferred to a complete Nissen fundoplication at the time of Heller myotomy given a lower respective rate of recurrent dysphagia (2.8% vs 15%, P < 0.001)[25]. The operation has evolved to the procedure introduced by Pellegrini in 1992, in which a minimally invasive single anterior myotomy is performed via a laparoscopic approach through the abdomen[26]. The laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) is currently the standard surgical approach for achalasia, due to the procedure’s lower morbidity and relatively similar long-term outcomes when compared with the more invasive thoracotomy approach[27], with rates of efficacy ranging from 88% to 95%[4,27]. Presently, several centers, including our own, offer robot-assisted LHM with excellent clinical results.

While the reported rates of clinical success with LHM have been consistently high, persistent or recurrent dysphagia does occur after LHM, which is usually due to an incomplete myotomy. Surgical expertise is an important predictor of good clinical outcomes, as more failures and complications occur during a surgeon’s first 50 operations[28]. Complications from LHM include GERD and its sequelae (18%), need to convert to an open procedure (2%), and mucosal perforations (6.9%), although perforations are frequently identified and closed at the time of operation[27]. Nevertheless, given the potential morbidity and the cost of the operation ($44839 in US Dollars for professional fees and facility charges for LHM with fundoplasty, when performed[29]), alternative, and less invasive therapies have been pursued particularly in patients with medical co-morbidities that might preclude surgery[30].

PD

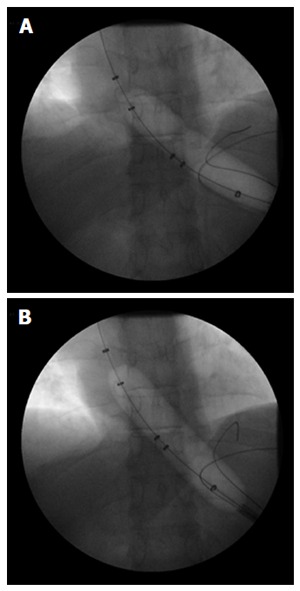

PD disrupts the LES by forceful stretching by using large-diameter, non-compliant, dilating balloon catheters. Commercially available PD balloons include the Rigiflex II system (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States) and the Achalasia Balloon Dilators (Hobbs Medical, Stafford Springs, CT, United States) that are available in 30 mm, 35 mm, and 40 mm diameters. The Achalasia Balloon (Cook Medical, Winston Salem, NC, United States) comes in 30 mm and 40 mm diameters. Other pneumatic dilating balloons are available outside the United States (Olympus Europa, Hamburg, Germany). With the aid of radio-opaque markers, the deflated balloon is positioned under fluoroscopic or endoscopic guidance across the LES[31]. The balloon is then gradually inflated until a fluoroscopic waist is identified across the mid-portion of the balloon that is subsequently obliterated by further dilation (Figure 3). Although this procedure has been widely performed for decades[32], no consensus exits with respect to the optimal distention protocol. Some operators only perform a single dilation[33], although most use graded dilations starting at 30 mm and then increasing in size on subsequent sessions every 2 to 4 wk based on symptom relief that is correlated with LES pressure[34,35]. Kadakia et al[35] reported an overall success rate of 93% (in 27 of 29 patients with achalasia) undergoing graded dilation from 30 mm to 40 mm with a Rigiflex balloon. Disparate data on success rates have been reported, ranging from 35% to 85% over several years of follow-up[36-41]. Over a mean follow-up period of 2.4 years, Dobrucali et al[31] observed a success rate, defined as improvement in overall symptoms, of 56% in (24 of 43) patients with achalasia who were pneumatically dilated with a 30-mm balloon. Subsequent dilation with a 35-mm balloon resulted in improvement in 78% of the remaining patients who did not have a good initial response. However, only 54% of patients with follow-up data available at 5 years were symptom-free. Nevertheless, graded dilation appeared to be more effective in achieving symptom relief over 3 years (86% response rate) as compared to a single 30-mm balloon dilation (37% response rate)[42].

Figure 3.

Pneumatic balloon dilation of the lower esophageal sphincter in a patient with achalasia. A 44-year-old man with type II achalasia underwent pneumatic dilation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) under fluoroscopic guidance to 30 mm in diameter. The pneumatic balloon catheter was passed across the LES over a wire and then inflated with initial evidence of a waist in the mid-portion of the balloon (A); The balloon was kept inflated until the waist in the balloon was obliterated (B). A barium esophagram done immediately following pneumatic dilation showed no evidence of perforation.

Predictors of poor response to PD include younger age (< 40 years) at presentation[42] and a shorter duration of symptoms prior to treatment[43]. Two of the most important factors in predicting the need for retreatment include incomplete obliteration of the waist of the balloon and post-treatment elevated LES pressures. Incomplete balloon-waist obliteration was reported to result in 5- and 10-year symptom recurrence rates of 64% and 72%, respectively. A 3-mo post-treatment LES pressure above 10 mmHg was associated with 5- and 10-year symptom recurrence rates of 25% and 33%, respectively[36,43]. Success also appeared to be predicated on the treatment being provided by experienced clinicians[38].

Overall, patients with characteristics that predict a poor outcome from PD should probably consider other options such as surgical or endoscopic myotomy. While rates of symptom improvement in a select group of patients following repeated PD for achalasia as high as 96.8% at 5 years and 93.4% at 10 years have been reported[41], many studies demonstrate that the treatment effect and symptom remission decreases over time[36,37,40]. Therefore, younger patients might be better managed with surgical or endoscopic myotomy, in light of possible diminishing returns with repeated PD[40].

Botulinum toxin injection

In patients with significant comorbidities who may not be good candidates for surgical or endoscopic myotomy, or even PD, pharmacologic therapies may be offered for symptomatic management of achalasia, although the efficacy of such an approach is typically limited. Endoscopy-directed botulinum toxin (BT) injection delivers pharmacologic therapy to the LES by blocking acetylcholine release from local nerve endings, thereby reducing LES tonicity[4]. Typically, 100 U of commercially available BT powder is dissolved in 5 mL of sterile normal saline, and this solution is injected in divided doses in to the muscularis propria of the GEJ. Our practice is to perform four quadrant injections (each containing 20 U of BT in 1 mL of solution) from the distal esophagus and one final injection (20 U of BT in 1 mL of solution) from the gastric cardia using a retroflexed scope position.

Cuillière et al[44] reported significant improvement in LES pressures after treatment and an improved symptom score at 2 wk, 2 mo, and 6 mo when compared with pretreatment values (P < 0.001). Of 31 patients treated with endoscopically-delivered BT injection to the LES, 28 improved initially, although sustained response was seen in only 20 patients beyond 3 mo with general response duration averaging 1.3 years[45]. The response rate tended to be greater in patients older than 50 years of age (82% vs 43% in younger patients, P = 0.03) and in patients with vigorous (type III) achalasia (100% vs 52% with classic achalasia, P = 0.03). The effect of “Botox” injection tends to be temporary due to axonal regeneration, with most studies demonstrating minimal clinical efficacy after 1 year[14,45,46]. Furthermore, repeated BT treatments can induce submucosal fibrosis of the esophagus and GEJ, which can make subsequent surgical or endoscopic myotomy more difficult, resulting in an increased risk of intraoperative perforation as well as a higher rate of procedural failure[47]. Given the above, we do not recommend empiric BT injections as a diagnostic test for achalasia.

Comparison of traditional therapies

The efficacies of the aforementioned conventional therapeutic modalities have been evaluated against one another. When considering the efficacy of LHM vs PD, several factors must be taken into account including the patient’s age, comorbid diseases that may preclude surgery or make complications (if they occur) potentially fatal, and prior therapies. Patients undergoing PD should be made aware of the possibility of perforation (overall median rate in experienced hands of 1.9% with a range of 0% to 16%)[3], as this complication would require inpatient observation, and could necessitate emergency esophageal stenting or even emergency surgery (including possible esophagectomy).

Okike et al[32] published one of the earliest and largest experiences comparing esophagomyotomy to forceful dilation of the esophagus for treatment of achalasia. Between 1949 and 1976, 431 patients underwent forceful hydrostatic or PD and 468 patients had an open transthoracic esophagomyotomy. Esophageal leaks and mediastinal sepsis occurred in 4% following dilation as compared to in 1% of patients following surgical myotomy, although no deaths resulted from these complications in either group. The 30-d mortality was 0.2% after myotomy and 0.5% after forceful dilation. The long-term results of esophagomyotomy were significantly better than those for forceful dilation (P < 0.001). Furthermore, 16% of patients in the dilation group were dilated twice and 2% required dilation three or more times.

Gockel et al[11] followed 89 patients diagnosed with achalasia between 1998 and 2002 who underwent either PD (64 patients) or Heller myotomy (25 patients) in combination with an anterior semi-fundoplication (Dor procedure) and demonstrated more markedly improved LES resting pressures on manometry at 6 mo in patients undergoing myotomy as compared to PD (7.9 mmHg vs 14.5 mmHg, P < 0.0001), suggesting the surgical approach to be superior.

When patient characteristics are favorable for PD, the clinical utility and cost of this procedure appear to beneficial relative to surgery[26,30,39]. A cost analysis performed by Parkman in 1993 suggested myotomy to be 5 times more costly than PD[39]. Moreover, even though the clinical benefit of repeat PD decreased over time, LHM remained at least 2.4 times greater in cost than treating with an initial PD. Using a Markov model, O’Connor et al[30] also demonstrated the overall favorable cost-effectiveness of PD compared to surgical myotomy over 5 years, which was driven by the high initial cost of surgery (incremental cost of $5376750 per quality-adjusted life-year, QALY).

In an important study published in 2011, Boeckxstaens et al[48] randomized 201 patients with achalasia to PD (n = 95) or LHM with a Dor fundoplication (n = 106) and reported a mean follow-up period of 43 mo. In an intention-to-treat analysis, there was no difference between the groups in the primary outcome of therapeutic success (as defined by a drop in the Eckardt quality-of-life score to ≤ 3) at 1 year (90% for PD vs 93% for LHM, P = 0.46). Similarly, no difference was found between the groups in decreased LES pressures at 1 year (10 mmHg for LHM vs 12 mmHg for PD, P = 0.27), which led the authors to conclude that LHM when compared to PD was not associated with superior rates of therapeutic success. Five-year follow-up data from the initial study demonstrated no significant difference in success rates between PD and LHM (82% vs 84%, respectively, P = 0.92), although re-dilation was necessary in 25% of patients undergoing PD[49]. This study reported that esophageal perforation occurred in 4% of the patients during PD, and mucosal tears occurred in 12% during LHM. In a smaller randomized study published in 2015, patients with early-stage achalasia who were randomized to LHM had a 96% rate of symptom relief vs 76% in patients who underwent PD (P = 0.04)[50]. This study reported comparable rates of adverse events as esophageal perforation occurred in 8% of patients during PD, whereas mucosal tears occurred in 4% of the patients during LHM.

As previously mentioned, the appropriate initial therapy for achalasia should be dictated by a patient’s clinical parameters, risk tolerance, and by locally available expertise. Although the risk of perforation with PD has variably been reported between 0% to 16%[3], Lynch et al[51] reported perforation in only 1 of 272 PD procedures (0.37%) over 12 years compared with 6 of 295 LHM procedures (2%) over a similar time period. There were no deaths in the PD group. These authors concluded that in high-volume centers PD had lower rates of complications and death compared with LHM. It should also be noted that both LHM and PD may result in post-treatment GERD, but only LHM can offers a simultaneous adjunctive procedure at the time of surgery to limit postprocedural reflux.

Studies comparing PD to BT injection have demonstrated improved clinical efficacy of PD in terms of immediate response and duration of response[14,52,53]. PD also tends to be more effective than BT from a cost-effectiveness standpoint[54] with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $1348 per QALY[30]. In a study comparing LHM to BT for symptom improvement in patients with achalasia, Zaninotto et al[46] randomized 40 patients to BT injection and 40 patients to LHM. At 6-mo follow-up, symptom scores were significantly better in the patients undergoing LHM compared with those undergoing BT injection (82% vs 66%, P < 0.05). The probability of being symptom-free at 2 years was 87.5% after surgery vs 34% after BT (P < 0.05). Despite being easy to perform and possessing a good safety profile, the limited clinical efficacy of BT injection to durably treat achalasia should limit its use to elderly patients who are considered to be unfit for surgery or as a salvage therapy following failure of other therapeutic modalities.

PER ORAL ENDOSCOPIC MYOTOMY

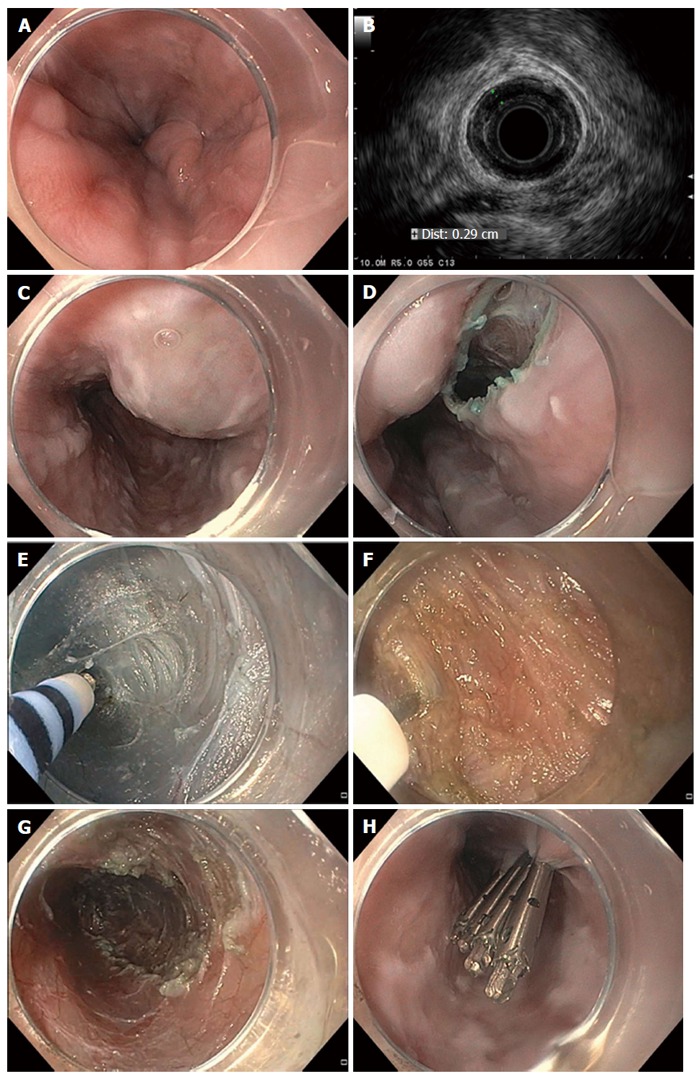

In an effort to minimize the potential complications and invasiveness of surgery and to improve upon the clinical efficacy of non-surgical therapy for achalasia, per oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) was conceived of by Pasricha in 2007 and performed in a porcine model[55]. Baseline LES pressures were measured in 4 pigs who subsequently underwent upper endoscopy. A submucosal saline injection was made 5 cm above the LES followed by a small entry incision in the mucosa to facilitate introduction of a dilating balloon and creation of a submucosal tunnel. The scope was then advanced towards the LES and circular deep muscle fibers were then incised using an electrosurgical knife. The endoscope was then withdrawn back into the lumen of the esophagus and the defect was closed using endoscopically applied clips. Manometry repeated on day 5 after the procedure demonstrated the LES pressures to have decreased from an average of 16.4 mmHg prior to myotomy to an average of 6.7 mmHg following myotomy.

Based on his expertise in endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), Inoue et al[56] believed that this procedure could be safely performed in patients, and he performed POEM in 17 consecutive patients with achalasia (10 men and 7 women with a mean age 41.4 years). Included in this series were 3 patients who had previously received an uncomplicated balloon dilation. A dysphagia-symptoms-score was assessed for each patient prior to and several times after the procedure to objectively gauge improvement in symptoms. A barium swallow (to evaluate the degree of esophageal dilation) and a computed tomography (CT) scan (to provide information on anatomical structures adjacent to the esophagus) were performed in all patients prior to POEM. Patients with sigmoid-type achalasia (esophagus demonstrated a “U-turn” or a “double-lumen” on CT) were initially excluded, but were later included after success with the first 5 cases. A CT scan was also obtained on the day of the procedure following POEM to evaluate for mediastinal emphysema, and a barium swallow was completed the day after POEM to confirm passage of contrast through the GEJ without leakage. Esophageal manometry was also completed prior to and after the procedure.

All 17 patients underwent successful POEM for achalasia under general anesthesia and by using carbon dioxide gas for insufflation. An anterior approach was taken for 16 of these POEM procedures. A 2-cm longitudinal mucosal incision was made in the mid-esophagus to allow a 9.8-mm diagnostic gastroscope with a distal attachment cap to gain access to the submucosal space. A Triangle Tip Knife (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to dissect the submucosal layer and also to divide the circular muscle bundles. Endoscopic myotomy was begun 3 cm distal to the mucosal entry point and the submucosal tunnel averaged 12.4 cm in length. The myotomy of the deep circular muscle bundles was carried out to a distance at least 2 cm distal to the GEJ in to the proximal stomach. Minor bleeding occurred during the POEM procedures and was easily controlled by endoscopic coagulation. Once the mucosal defect was endoscopically closed with standard endoclips, substantial reduction in LES tone was confirmed by passing the endoscope through the lumen of the esophagus. Furthermore, patients’ dysphagia symptom scores decreased from a mean of 10 prior to POEM to a mean of 1.3 following the procedure (P = 0.0003), and mean LES pressure decreased from 52.4 mmHg to 19.8 mmHg (P = 0.0001) after POEM[56].

Subsequently in 2015, Inoue et al[57] published their results from a cohort of 500 patients who all underwent successful POEM. Short- and long-term follow-up was reported. These investigators found a significant reduction in Eckardt scores and LES pressures at 2 mo, 1 year, and 3 years following POEM as compared to baseline values. Adverse events were observed in 16 of 500 patients (3.2%), which included 1 pneumothorax with mediastinal emphysema, 8 mucosal injuries, 3 postoperative hematomas, 1 case of inflammation in the lesser omentum, and 2 cases of pleural effusion. GERD was the biggest delayed complication of the procedure, which was reported in 16.8% of patients at 2 mo and 21.3% at 3-year follow-up. Length of hospital stay in this series was a median of 4 d (range of 4 to 5 d) after POEM, and no perioperative mortalities occurred.

The POEM procedure, and the equipment used to perform it, continue to be refined at a number of centers of expertise around the world, with similar results and complications as those in Inoue’s series having been described in subsequent series[58-68] (Figure 4). Most endoscopists experienced with ESD no longer routinely use balloon dilation to create a submucosal tunnel, rather the tunnel is created by using electrosurgical dissection taking care to stay close to the deep muscle layer (as for a POEM, perforation is actually causing injury to the esophageal mucosa as opposed to the muscularis propria and adventitia).

Figure 4.

Per oral endoscopic myotomy in a patient with achalasia. A 56-year-old man with type II achalasia and a history of chronic alcohol use underwent attempted laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Upon retraction of the liver during surgery, large gastroesophageal varices were noted to arise and the surgery was aborted. The patient was exhorted to stop drinking alcohol. Doppler ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging with arterial and venous phase imaging did not show any significant gastroesophageal varices or obvious portal hypertension. Per oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) was performed. Endoscopic views in the distal esophagus found some enlarged veins but no high-grade esophageal or gastric varices (A); Radial endosonography found a thickened deep circular muscle layer measuring 2.9 mm, which is commonly found in patients with achalasia, but no obvious esophageal varices were noted (B); A mucosal weal was created by injecting saline tinted with indigo carmine (C); and a mucosal entry incision was made (D); Submucosal dissection was carried out with sequential injection and electrosurgical dissection (E) using a T-type Hybrid knife in conjunction with an ERBEJET 2 and a VIO 300 D generator set at EndoCut Q 3-2-1 (ERBE, Marietta, GA, United States). Dissection of the circular layer of the muscularis propria was performed using the T-type Hybrid knife (F); After completion of the 7-cm-long myotomy in the distal esophagus that was carried out an additional 2 cm into the gastric cardia (G); the mucosal entry site was closed by using endoclips (H). The patient did well without any intra- or post-procedural bleeding. At clinic follow-up 2 mo later, the patient reported complete resolution of his symptoms of dysphagia and weight gain of 14 lbs.

The first prospective series of POEMs performed in Europe included 16 patients and achieved success in 94% of cases, with reduction in LES pressures from a mean of 27.2 mmHg prior to POEM to 11.8 mmHg following treatment. Furthermore, none of the patients subsequently developed GERD[69]. Similar rates of overall success and complications were corroborated by the International POEM Survey (IPOEMS), which involved 16 expert centers[70].

A meta-analysis that included 4 studies of patients with achalasia who underwent LHM vs POEM reported that POEM patients had comparable rates of complications (OR = 1.17, P = 0.7), postprocedural GERD (OR = 1.00, P = 1.00), and symptomatic recurrence by Eckardt score (OR = 0.24, P = 0.13), with no difference in other outcomes including pain scores, operating times, and length of hospital stays when compared to those who had LHM[71]. In a separate study, quality-of-life assessments based on the SF-36 instrument in patients who underwent POEM increased at 3 wk, 6 mo, and 1 year following the procedure, which was comparable to the results seen following LHM[72]. Kumbhari et al[73] compared 49 patients with type III achalasia who underwent POEM across 8 international centers to 26 patients who underwent LHM at a single institution. Despite patients in the POEM arm receiving a longer-length myotomy (16 cm vs 8 cm, P < 0.01), POEM procedures were completed in a significantly shorter mean procedure time (102 min vs 264 min, P < 0.01), and patients who underwent POEM had significantly better clinical response (98.0% vs 80.8%, P = 0.01), as compared to those who underwent LHM. These authors surmised that patients with type III achalasia had a better clinical response following POEM than after LHM in this study because POEM enables a longer-length myotomy, as the endoscopic approach provides access to the esophageal body.

Furthermore, POEM was reported to have been safely performed and effective in a series of 40 consecutive patients that included 12 who had previously undergone PD or BT injection[74]. In this study, 12 patients had undergone previous alternative therapies, while 28 patients had received no intervention prior to POEM. There was no statistical difference in the 6-mo postoperative median Eckardt scores between the two groups (1 vs 1, P = 0.4). Ling et al[75] also reported on 21 patients who underwent POEM following failed PD. In that series, there was no statistical difference in postprocedural Eckhart scores, LES pressures, esophageal emptying, or quality-of-life indicators in those patients who had undergone failed PD prior to POEM compared with 30 control patients who had no intervention prior to POEM. However, mean POEM operating time was longer in the failed PD group (42.4 min) compared with the control group (34.3 min, P = 0.01). Alternatively, in a study with 40 patients, Orenstein et al[76] reported no statistical difference in operating times, GERD metrics, and SF-12 scores between patients who had undergone no interventions prior to POEM and those who had undergone prior interventions (including BT injection, balloon dilation, or surgical myotomy). The authors did state that a different approach was necessary in patients who had failed Heller myotomy as an anterior approach would not be effective and significant scarring could be encountered. In this situation, most experts perform POEM with the mucosal entry site and subsequent myotomy along the posterior wall of the esophagus.

As of 2016, we now have relatively robust, published data that demonstrate POEM to be an effective, minimally-invasive therapy for achalasia with similar outcomes to LHM. As POEM is now routinely performed by numerous experts in referral centers worldwide, additional comparative studies with long-term follow-up should be forthcoming. At present, the technique of performing POEM (type of knife used, type of electrosurgical current used at various steps in the procedure, isolated incision of the deep circular muscle vs full-thickness incision, etc.) and the optimal pre- and post-procedural protocol continue to be refined and can vary among high-volume centers.

For instance, in the IPOEMS survey, 88% of those surveyed reported obtaining routine early postoperative radiographic imaging[70]. Sternbach et al[77] subsequently evaluated the ability of barium esophagram obtained on postoperative day (POD) 1 in 72 patients undergoing POEM to predict symptomatic and physiologic outcomes at 1-year follow-up. Those patients found to have delayed esophageal emptying on barium esophagram performed on POD 1 had no difference at 1 year with respect to Eckhart scores, barium height at 5 min, or need for retreatment when compared with those patients without delayed emptying on barium esophagram. Despite these data, most centers still perform a barium esophagram within 1 d following POEM to rule out perforation, in addition to serving as an early indicator of efficacy following POEM.

As mentioned above, the endosurgical technique used to perform POEM can vary among centers, which is a phenomenon also seen with ESD. POEM has classically involved the use of separate devices to successively inject saline tinted with a blue dye (diluted indigo carmine or methylene blue) into the submucosal space, followed by dissection with an ESD knife (such as a DualKnife or Triangle Tip Knife, Olympus America, Center Valley, PA or an I-type or T-type Hybrid Knife, ERBE, Marietta, GA) in a sequential and repeated fashion.

However, in a recent cohort of 9 patients undergoing POEM, repeated water-jet injection of tinted saline through the dedicated channel of the gastroscope (thereby mitigating the need for an injection needle) resulted in consistent staining of the submucosal fibers, which enabled accurate, efficient, and safe dissection with a Triangle Tip Knife[78]. Cai et al[79] further demonstrated differing procedural times in 100 patients undergoing POEM who were randomized to the conventional multi-device technique (using a 23G injector needle and a TT Knife, Olympus) or to use of a HybridKnife (I-type or T-type, ERBE) with an ERBEJet2 (ERBE) system that enables atraumatic submucosal injection of saline as well as electrosurgical dissection by using a single endoscopic device. The group that underwent POEM with the HybridKnife had a significantly shorter average procedure duration (22.9 min), without any severe complications, compared with the group that underwent POEM with the conventional multi-device technique (35.2 min, P < 0.0001). Other commercially available knives that enable both injection and electrosurgical incision and dissection are expected to be made available in the United States in 2016-2017.

Overall, POEM is a significant addition to the armamentarium of the interventional or surgical endoscopist for the endoscopic treatment of achalasia. It is our belief that the most effective treatment for patients with achalasia is the precise visualization and incision of the dysfunctional circular muscle of the distal esophagus, the LES, and the proximal gastric cardia. We believe that irrespective to how the myotomy is performed - whether by using a robot-assisted or laparoscopic surgical approach or by using a flexible endoscope - as long as a proper myotomy is achieved, the treatment results should be equivalent. What might differ between an endoscopic and a surgical approach might be the rates or types of complications. Furthermore, with ever changing and decreasing procedural reimbursement, particularly for flexible endoscopy codes in the United States, the relative cost of LHM vs POEM is likely to change-probably in favor of POEM. With additional comparative long-term data and multi-center reports, we believe that POEM will likely become a widely accepted and effective endoscopic therapy for achalasia.

OTHER ENDOSCOPIC INNOVATIONS

Other endoscopic advancements that might help patients with achalasia include use of the Endolumenal Functional Lumen Imaging Probe system (EndoFLIP, Crospon, Carlsbad, CA, United States) to measure LES distensibility at the time of POEM in order to improve long-term outcomes by giving an intraprocedural indicator of the adequacy of the myotomy prior to tunnel closure[80]. Additional innovative endoscopic ideas in this field have included injection of ethanolamine at the GEJ as a cheaper but clinically equivalent alternative to BT[81], as well as temporary use of a large caliber 30-mm self-expandable metal stent[82] for symptomatic improvement in patients with achalasia (which is not commercially available or approved for use in the United States). Of course, as with other currently accepted techniques for treating achalasia, robust data denoting successful long-term outcomes with acceptable risk profiles will be required prior to generalized use of any new and innovative techniques.

IMPORTANCE OF COUNSELING

Regardless of whether PD, LHM, or POEM is performed, all proceduralists strive for ideal outcomes with no or few complications. However, it should be underscored that achalasia is a lifelong disease with no cure. At best, the goal of pharmacologic, radiographic, endoscopic, or surgical treatment of achalasia is to allow patients to eat better (without constant dysphagia), maintain their weight, and reduce the risk of developing a megaesophagus. Patients must understand that they will never eat “normally” as they did prior to being diagnosed with achalasia. In particular, following a complete myotomy (regardless of whether it is by LHM or POEM), patients can never lay flat because of the risk of aspiration from an incompetent LES. Also, patients must be careful to swallow only small quantities of well-chewed food and to allow gravity with adequate time to allow this manageable food bolus to pass from the esophagus into the stomach. Patients with successful and complete myotomies who swallow too much food in too quick a manner are prone to “overflowing” the 7-to-10-cm-long myotomy in their distal esophagus, which can lead to symptoms of dysphagia and regurgitation from food that is backed-up in the non-treated mid-to-proximal esophagus, thereby mimicking an incomplete myotomy.

CONCLUSION

Endoscopy is an important tool in the diagnostic workup of achalasia. Endoscopic therapies also offer a range of minimally invasive treatments for patients with this non-malignant but incurable disease. Overall, the choice of which therapy to use to treat a patient with achalasia should be based on clinical factors including the patient’s age, medical comorbidities, risk tolerance, and the local expertise of the managing physicians. HRM should be obtained to definitively diagnose achalasia, as it also enables the diagnosis of the subtype of achalasia, which in turn might help guide treatment. We generally counsel patients on the long-term data supporting use of PD or surgical myotomy, and we also give patients the option to pursue POEM as a minimally-invasive endoscopic alternative to LHM.

Based on presently available data, we believe that both LHM and POEM, when done properly by an experienced surgeon or endoscopist, can achieve excellent clinical results, particularly in patients with type I or type II achalasia. Furthermore, we feel it reasonable to proceed with myotomy (either LHM or POEM) as first-line therapy over pharmacologic options including BT injection in younger, healthier patients. However, in patients with limited life expectancy or those who are poor operative candidates, less invasive therapies such as repeated BT injection or even percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement are appropriate considerations. While PD is effective and can be repeated, if required, the random disruption of the LES and deep muscle layer of the distal esophagus can make subsequent LHM or POEM more challenging and more dangerous.

Ultimately, thoughtful and tailored application of various therapies for patients with achalasia can provide long-term symptomatic improvement. Despite this optimism, the data do show that recurrent symptoms can occur up to years later following successful LHM, POEM, or PD. However, re-treatment is possible typically by PD or POEM at a site that has not undergone prior myotomy. Patient counselling and behavioral modification are paramount to achieving good postprocedural outcomes, as achalasia can only be treated but not cured. Finally, endoscopic management may also extend to screening for malignancy in patients with achalasia as their risk of esophageal cancer is increased. However, with limited data and no official recommendations regarding endoscopic screening, decisions regarding whether or not to screen and how frequently to do this falls on the judgment of the treating physician in consultation with his or her patient.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to report with respect to this manuscript. Dr. Wang discloses that he has received research funding from Cook Medical on the topic of metal biliary stents.

Peer-review started: March 29, 2016

First decision: May 12, 2016

Article in press: September 14, 2016

P- Reviewer: Luo LS S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Fisichella PM, Patti MG. From Heller to POEM (1914-2014): a 100-year history of surgery for Achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1870–1875. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2547-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richter JE. Oesophageal motility disorders. Lancet. 2001;358:823–828. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05973-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1238–1249; quiz 1250. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pandolfino JE, Gawron AJ. Achalasia: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313:1841–1852. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boeckxstaens GE. Achalasia: virus-induced euthanasia of neurons? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1610–1612. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisichella PM, Raz D, Palazzo F, Niponmick I, Patti MG. Clinical, radiological, and manometric profile in 145 patients with untreated achalasia. World J Surg. 2008;32:1974–1979. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9656-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moonen A, Boeckxstaens G. Current diagnosis and management of achalasia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:484–490. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohof WO, Salvador R, Annese V, Bruley des Varannes S, Chaussade S, Costantini M, Elizalde JI, Gaudric M, Smout AJ, Tack J, et al. Outcomes of treatment for achalasia depend on manometric subtype. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:718–725; quiz e13-14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckardt VF. Clinical presentations and complications of achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:281–292, vi. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckardt VF, Köhne U, Junginger T, Westermeier T. Risk factors for diagnostic delay in achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:580–585. doi: 10.1023/a:1018855327960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gockel I, Eckardt VF, Schmitt T, Junginger T. Pseudoachalasia: a case series and analysis of the literature. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:378–385. doi: 10.1080/00365520510012118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucchinetti CF, Kimmel DW, Lennon VA. Paraneoplastic and oncologic profiles of patients seropositive for type 1 antineuronal nuclear autoantibodies. Neurology. 1998;50:652–657. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.3.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Oliveira JM, Birgisson S, Doinoff C, Einstein D, Herts B, Davros W, Obuchowski N, Koehler RE, Richter J, Baker ME. Timed barium swallow: a simple technique for evaluating esophageal emptying in patients with achalasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:473–479. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.2.9242756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Wilcox CM, Schroeder PL, Birgisson S, Slaughter RL, Koehler RE, Baker ME. Botulinum toxin versus pneumatic dilatation in the treatment of achalasia: a randomised trial. Gut. 1999;44:231–239. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howard PJ, Maher L, Pryde A, Cameron EW, Heading RC. Five year prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and diagnosis of achalasia in Edinburgh. Gut. 1992;33:1011–1015. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.8.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE, Rice J, Clarke JO, Kwiatek M, Kahrilas PJ. Impaired deglutitive EGJ relaxation in clinical esophageal manometry: a quantitative analysis of 400 patients and 75 controls. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G878–G885. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00252.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE, Zhang Q, Jarosz A, Shah N, Kahrilas PJ. Quantifying esophageal peristalsis with high-resolution manometry: a study of 75 asymptomatic volunteers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G988–G997. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00510.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Gyawali CP, Roman S, Smout AJ, Pandolfino JE. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:160–174. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: Clinical use of esophageal manometry. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:207–208. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandolfino JE, Kwiatek MA, Nealis T, Bulsiewicz W, Post J, Kahrilas PJ. Achalasia: a new clinically relevant classification by high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1526–1533. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yadlapati R, Pandolfino JE. Achalsaia Update: No Longer a Tough Diagnosis to Swallow. The New Gastroenterologist; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duranceau A, Liberman M, Martin J, Ferraro P. End-stage achalasia. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:319–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gockel I, Junginger T. The value of scoring achalasia: a comparison of current systems and the impact on treatment--the surgeon’s viewpoint. Am Surg. 2007;73:327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stavropoulos SN, Friedel D, Modayil R, Iqbal S, Grendell JH. Endoscopic approaches to treatment of achalasia. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6:115–135. doi: 10.1177/1756283X12468039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rebecchi F, Giaccone C, Farinella E, Campaci R, Morino M. Randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Heller myotomy plus Dor fundoplication versus Nissen fundoplication for achalasia: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2008;248:1023–1030. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318190a776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richter JE, Boeckxstaens GE. Management of achalasia: surgery or pneumatic dilation. Gut. 2011;60:869–876. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.212423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campos GM, Vittinghoff E, Rabl C, Takata M, Gadenstätter M, Lin F, Ciovica R. Endoscopic and surgical treatments for achalasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2009;249:45–57. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e43ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharp KW, Khaitan L, Scholz S, Holzman MD, Richards WO. 100 consecutive minimally invasive Heller myotomies: lessons learned. Ann Surg. 2002;235:631–638; discussion 638-639. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200205000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meara MP, Perry KA, W HJ. Economic Impact of Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy Versus Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy and Endoscopic Pneumatic Dilation. Surg Endosc. 2014;28 Suppl 1:S339. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor JB, Singer ME, Imperiale TF, Vaezi MF, Richter JE. The cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1516–1525. doi: 10.1023/a:1015811001267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dobrucali A, Erzin Y, Tuncer M, Dirican A. Long-term results of graded pneumatic dilatation under endoscopic guidance in patients with primary esophageal achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3322–3327. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okike N, Payne WS, Neufeld DM, Bernatz PE, Pairolero PC, Sanderson DR. Esophagomyotomy versus forceful dilation for achalasia of the esophagus: results in 899 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1979;28:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)63767-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eckardt VF, Aignherr C, Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1732–1738. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hulselmans M, Vanuytsel T, Degreef T, Sifrim D, Coosemans W, Lerut T, Tack J. Long-term outcome of pneumatic dilation in the treatment of achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadakia SC, Wong RK. Graded pneumatic dilation using Rigiflex achalasia dilators in patients with primary esophageal achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eckardt VF, Gockel I, Bernhard G. Pneumatic dilation for achalasia: late results of a prospective follow up investigation. Gut. 2004;53:629–633. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.029298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karamanolis G, Sgouros S, Karatzias G, Papadopoulou E, Vasiliadis K, Stefanidis G, Mantides A. Long-term outcome of pneumatic dilation in the treatment of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:270–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz PO, Gilbert J, Castell DO. Pneumatic dilatation is effective long-term treatment for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1973–1977. doi: 10.1023/a:1018886626144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parkman HP, Reynolds JC, Ouyang A, Rosato EF, Eisenberg JM, Cohen S. Pneumatic dilatation or esophagomyotomy treatment for idiopathic achalasia: clinical outcomes and cost analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:75–85. doi: 10.1007/BF01296777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.West RL, Hirsch DP, Bartelsman JF, de Borst J, Ferwerda G, Tytgat GN, Boeckxstaens GE. Long term results of pneumatic dilation in achalasia followed for more than 5 years. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1346–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zerbib F, Thétiot V, Richy F, Benajah DA, Message L, Lamouliatte H. Repeated pneumatic dilations as long-term maintenance therapy for esophageal achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:692–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farhoomand K, Connor JT, Richter JE, Achkar E, Vaezi MF. Predictors of outcome of pneumatic dilation in achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:389–394. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alderliesten J, Conchillo JM, Leeuwenburgh I, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ. Predictors for outcome of failure of balloon dilatation in patients with achalasia. Gut. 2011;60:10–16. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.211409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cuillière C, Ducrotté P, Zerbib F, Metman EH, de Looze D, Guillemot F, Hudziak H, Lamouliatte H, Grimaud JC, Ropert A, et al. Achalasia: outcome of patients treated with intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin. Gut. 1997;41:87–92. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pasricha PJ, Rai R, Ravich WJ, Hendrix TR, Kalloo AN. Botulinum toxin for achalasia: long-term outcome and predictors of response. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1410–1415. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zaninotto G, Annese V, Costantini M, Del Genio A, Costantino M, Epifani M, Gatto G, D’onofrio V, Benini L, Contini S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of botulinum toxin versus laparoscopic heller myotomy for esophageal achalasia. Ann Surg. 2004;239:364–370. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000114217.52941.c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith CD, Stival A, Howell DL, Swafford V. Endoscopic therapy for achalasia before Heller myotomy results in worse outcomes than heller myotomy alone. Ann Surg. 2006;243:579–584; discussion 584-586. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217524.75529.2d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boeckxstaens GE, Annese V, des Varannes SB, Chaussade S, Costantini M, Cuttitta A, Elizalde JI, Fumagalli U, Gaudric M, Rohof WO, et al. Pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy for idiopathic achalasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1807–1816. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moonen A, Annese V, Belmans A, Bredenoord AJ, Bruley des Varannes S, Costantini M, Dousset B, Elizalde JI, Fumagalli U, Gaudric M, et al. Long-term results of the European achalasia trial: a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Gut. 2016;65:732–739. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamdy E, El Nakeeb A, El Hanfy E, El Hemaly M, Salah T, Hamed H, El Hak NG. Comparative Study Between Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy Versus Pneumatic Dilatation for Treatment of Early Achalasia: A Prospective Randomized Study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25:460–464. doi: 10.1089/lap.2014.0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lynch KL, Pandolfino JE, Howden CW, Kahrilas PJ. Major complications of pneumatic dilation and Heller myotomy for achalasia: single-center experience and systematic review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1817–1825. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jung HE, Lee JS, Lee TH, Kim JN, Hong SJ, Kim JO, Kim HG, Jeon SR, Cho JY. Long-term outcomes of balloon dilation versus botulinum toxin injection in patients with primary achalasia. Korean J Intern Med. 2014;29:738–745. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2014.29.6.738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leyden JE, Moss AC, MacMathuna P. Endoscopic pneumatic dilation versus botulinum toxin injection in the management of primary achalasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(2):CD005046. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005046.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Richter JE. Comparison and cost analysis of different treatment strategies in achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:359–370, viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pasricha PJ, Hawari R, Ahmed I, Chen J, Cotton PB, Hawes RH, Kalloo AN, Kantsevoy SV, Gostout CJ. Submucosal endoscopic esophageal myotomy: a novel experimental approach for the treatment of achalasia. Endoscopy. 2007;39:761–764. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Inoue H, Minami H, Kobayashi Y, Sato Y, Kaga M, Suzuki M, Satodate H, Odaka N, Itoh H, Kudo S. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia. Endoscopy. 2010;42:265–271. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inoue H, Sato H, Ikeda H, Onimaru M, Sato C, Minami H, Yokomichi H, Kobayashi Y, Grimes KL, Kudo SE. Per-Oral Endoscopic Myotomy: A Series of 500 Patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen X, Li QP, Ji GZ, Ge XX, Zhang XH, Zhao XY, Miao L. Two-year follow-up for 45 patients with achalasia who underwent peroral endoscopic myotomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47:890–896. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Costamagna G, Marchese M, Familiari P, Tringali A, Inoue H, Perri V. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for oesophageal achalasia: preliminary results in humans. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khashab MA, Messallam AA, Onimaru M, Teitelbaum EN, Ujiki MB, Gitelis ME, Modayil RJ, Hungness ES, Stavropoulos SN, El Zein MH, et al. International multicenter experience with peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of spastic esophageal disorders refractory to medical therapy (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1170–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee BH, Shim KY, Hong SJ, Bok GH, Cho JH, Lee TH, Cho JY. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for treatment of achalasia: initial results of a korean study. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:161–167. doi: 10.5946/ce.2013.46.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ling TS, Guo HM, Yang T, Peng CY, Zou XP, Shi RH. Effectiveness of peroral endoscopic myotomy in the treatment of achalasia: a pilot trial in Chinese Han population with a minimum of one-year follow-up. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:352–358. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Minami H, Isomoto H, Yamaguchi N, Matsushima K, Akazawa Y, Ohnita K, Takeshima F, Inoue H, Nakao K. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for esophageal achalasia: clinical impact of 28 cases. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:43–51. doi: 10.1111/den.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ren Z, Zhong Y, Zhou P, Xu M, Cai M, Li L, Shi Q, Yao L. Perioperative management and treatment for complications during and after peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia (EA) (data from 119 cases) Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3267–3272. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2336-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Swanstrom LL, Kurian A, Dunst CM, Sharata A, Bhayani N, Rieder E. Long-term outcomes of an endoscopic myotomy for achalasia: the POEM procedure. Ann Surg. 2012;256:659–667. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826b5212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Swanström LL, Rieder E, Dunst CM. A stepwise approach and early clinical experience in peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of achalasia and esophageal motility disorders. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:751–756. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verlaan T, Rohof WO, Bredenoord AJ, Eberl S, Rösch T, Fockens P. Effect of peroral endoscopic myotomy on esophagogastric junction physiology in patients with achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Von Renteln D, Fuchs KH, Fockens P, Bauerfeind P, Vassiliou MC, Werner YB, Fried G, Breithaupt W, Heinrich H, Bredenoord AJ, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of achalasia: an international prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:309–311.e1-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.von Renteln D, Inoue H, Minami H, Werner YB, Pace A, Kersten JF, Much CC, Schachschal G, Mann O, Keller J, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of achalasia: a prospective single center study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:411–417. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stavropoulos SN, Modayil RJ, Friedel D, Savides T. The International Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy Survey (IPOEMS): a snapshot of the global POEM experience. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3322–3338. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2913-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wei M, Yang T, Yang X, Wang Z, Zhou Z. Peroral esophageal myotomy versus laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy for achalasia: a meta-analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25:123–129. doi: 10.1089/lap.2014.0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vigneswaran Y, Tanaka R, Gitelis M, Carbray J, Ujiki MB. Quality of life assessment after peroral endoscopic myotomy. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1198–1202. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3793-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kumbhari V, Tieu AH, Onimaru M, El Zein MH, Teitelbaum EN, Ujiki MB, Gitelis ME, Modayil RJ, Hungness ES, Stavropoulos SN, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) vs laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) for the treatment of Type III achalasia in 75 patients: a multicenter comparative study. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E195–E201. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharata A, Kurian AA, Dunst CM, Bhayani NH, Reavis KM, Swanström LL. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) is safe and effective in the setting of prior endoscopic intervention. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1188–1192. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ling T, Guo H, Zou X. Effect of peroral endoscopic myotomy in achalasia patients with failure of prior pneumatic dilation: a prospective case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1609–1613. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Orenstein SB, Raigani S, Wu YV, Pauli EM, Phillips MS, Ponsky JL, Marks JM. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) leads to similar results in patients with and without prior endoscopic or surgical therapy. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1064–1070. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sternbach JM, El Khoury R, Teitelbaum EN, Soper NJ, Pandolfino JE, Hungness ES. Early esophagram in per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for achalasia does not predict long-term outcomes. Surgery. 2015;158:1128–1135; discussion 1135-1136. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Khashab MA, Messallam AA, Saxena P, Kumbhari V, Ricourt E, Aguila G, Roland BC, Stein E, Nandwani M, Inoue H, et al. Jet injection of dyed saline facilitates efficient peroral endoscopic myotomy. Endoscopy. 2014;46:298–301. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1359024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cai MY, Zhou PH, Yao LQ, Xu MD, Zhong YS, Li QL, Chen WF, Hu JW, Cui Z, Zhu BQ. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for idiopathic achalasia: randomized comparison of water-jet assisted versus conventional dissection technique. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1158–1165. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Teitelbaum EN, Soper NJ, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ, Hirano I, Boris L, Nicodème F, Lin Z, Hungness ES. Esophagogastric junction distensibility measurements during Heller myotomy and POEM for achalasia predict postoperative symptomatic outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:522–528. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3733-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mikaeli J, Veisari AK, Fazlollahi N, Mehrabi N, Soleimani HA, Shirani S, Malekzadeh R. Ethanolamine oleate versus botulinum toxin in the treatment of idiopathic achalasia. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:229–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cheng YS, Ma F, Li YD, Chen NW, Chen WX, Zhao JG, Wu CG. Temporary self-expanding metallic stents for achalasia: a prospective study with a long-term follow-up. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5111–5117. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i40.5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]