Abstract

The phylogeny of the insect infraorder Bibionomorpha (Diptera) is reconstructed based on the combined analysis of three nuclear (18S, 28S, CAD) and three mitochondrial (12S, 16S, COI) gene markers. All the analyses strongly support the monophyly of Bibionomorpha in both the narrow (sensu stricto) and the broader (sensu lato) concepts. The major lineages of Bibionomorpha sensu lato (Sciaroidea, Bibionoidea, Anisopodoidea, and Scatopsoidea) and most of the included families are supported as monophyletic groups. Axymyiidae was not found to be part of Bibionomorpha nor was it found to be its sister group. Bibionidae was paraphyletic with respect to Hesperinidae and Keroplatidae was paraphyletic with respect to Lygistorrhinidae. The included Sciaroidea incertae sedis (except Ohakunea Edwards) were found to belong to one clade, but the relationships within this group and its position within Sciaroidea require further study.

Keywords: Lower Diptera, Sciaroidea, Phylogenetic analysis, Molecular markers, Systematics

Introduction

Bibionomorpha is one of the approximately 10 infraorders currently recognized in the megadiverse insect order Diptera (Wood & Borkent, 1989; Oosterbroek & Courtney, 1995; Wiegmann et al., 2011). Although the composition of Bibionomorpha remains controversial, in the strictest sense (following principally Wood & Borkent, 1989) it comprises 12 extant families of lower Diptera: Bibionidae, Bolitophilidae, Cecidomyiidae, Diadocidiidae, Ditomyiidae, Hesperinidae, Keroplatidae, Lygistorrhinidae, Mycetophilidae, Pachyneuridae, Rangomaramidae, and Sciaridae. Broader concepts of Bibionomorpha also include Anisopodidae sensu lato (including Mycetobia Meigen, 1818, Olbiogaster Osten-Sacken, 1886 and related genera in the sense of Michelsen, 1999), Canthyloscelidae, Scatopsidae, and sometimes even Axymyiidae and Perissommatidae (see e.g., Hennig, 1973; Oosterbroek & Courtney, 1995; Wiegmann et al., 2011; Lambkin et al., 2013). The principally fossil family Valeseguyidae (with one extant species), placed in Scatopsoidea by Amorim & Grimaldi (2006), belongs to Bibionomorpha as well. Additionally, several enigmatic genera that certainly belong to Bibionomorpha have not yet been definitely assigned to a family. These taxa were traditionally treated as the Heterotricha Loew, 1850 group but in recent years have been referred to as Sciaroidea incertae sedis (Chandler, 2002; Jaschhof, 2011; Hippa & Ševčík, 2014).

In terms of biodiversity, Bibionomorpha is a megadiverse group due to the inclusion of the fungus gnats (Sciaroidea, comprising the very large families Mycetophilidae and Sciaridae) and gall midges (family Cecidomyiidae), the latter presumably even being the most diverse and species-rich family of Diptera (cf. Hebert et al., 2016). The number of extant species of Bibionomorpha sensu lato currently described has been estimated at 15,000 (Pape, Bickel & Meier, 2009), although an inestimable number of species in this group still remain uncollected and undescribed. Moreover, fungus gnats and gall midges are notoriously abundant in trap catches (e.g., Malaise traps) from terrestrial habitats, especially mesic forests. Various subgroups of Bibionomorpha are the most speciose among fossil Diptera, being well represented in the fossil record since the Mesozoic and impressively documented from different ambers (Evenhuis, 1994; Blagoderov & Grimaldi, 2004; Grimaldi, Engel & Nascimbene, 2002; Hoffeins & Hoffeins, 2014).

The larval diets of Bibionomorpha are diverse, including detritophagy, saprophagy, predation, mycophagy and phytophagy. Mycophagy has been considered to be ancestral in Sciaroidea, and predation ancestral in Keroplatidae (Matile, 1997). However, these conclusions were based on relatively little empirical evidence and the biology of most Bibionomorpha, even on a generic level, remains understudied. As a notable exception, the biology of many phytophagous Cecidomyiidae has been studied in great detail (e.g., Gagné & Moser, 2013). As for adults, fungus gnats are certainly the most conspicuous bibionomorphs, since they are both abundant (usually aggregating in large numbers at the trunks of fallen, rotten trees, along stream banks, and at similar moist, shady places) and big enough to be noticed with the naked eye. Species of Bibionidae occurring in enormous numbers during spring are widely known, even among general naturalists, as March flies, or lovebugs.

In accordance with the significance of the group, the phylogenic relationships within Bibionomorpha have been studied many times, often with the aim to establish a natural family classification. Among the studies based on morphology are those by Hennig (1954), Hennig (1973), Rohdendorf (1964), Rohdendorf (1974), Rohdendorf (1977), Wood & Borkent (1989), Oosterbroek & Courtney (1995), Matile (1997), Fitzgerald (2004), Amorim & Rindal (2007) and Lambkin et al. (2013). Even so, the phylogenetic relationships within Bibionomorpha are still far from being clarified (e.g., Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann, 2008). This is especially true in the Sciaroidea (including Bolitophilidae, Cecidomyiidae, Diadocidiidae, Ditomyiidae, Keroplatidae, Lygistorrhinidae, Mycetophilidae, Rangomaramidae, and Sciaridae) as several contradictory hypotheses have been proposed and debated in recent years (Matile, 1990; Matile, 1997; Chandler, 2002; Hippa & Vilkamaa, 2005; Hippa & Vilkamaa, 2006; Amorim & Rindal, 2007; reviewed by Jaschhof, 2011). As a result, one could get the impression that the morphology of adults (for various reasons larvae have not been studied in as much detail) cannot provide us with new and solid arguments in phylogenetic debates. For this reason, molecular approaches became the focus of Sciaroidea researchers, which seems natural considering that new characters are needed to advance the phylogenetic discussion and that the rapid development of molecular methods has raised great expectations. Molecular approaches have only recently been applied to phylogenetic studies of Bibionomorpha, but these studies focused either on certain subtaxa (e.g., Rindal, Søli & Bachmann, 2009; Ševčík, Kaspřák & Tóthová, 2013; Ševčík et al., 2014; Shin et al., 2013) or had a major focus beyond the infraorder (Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann, 2008; Wiegmann et al., 2011; Beckenbach, 2012). As a consequence, taxon sampling was not adjusted to tackle the issues specific to Bibionomorpha.

There are a number of unresolved questions regarding Bibionomorpha phylogeny that we have aimed to address in this study:

Firstly, the delimitation of the infraorder (sensu stricto versus sensu lato) remains unclear, especially regarding the question whether families, such as Anisopodidae sensu lato, Scatopsidae, Canthyloscelidae, Axymyiidae, and Perissommatidae, belong to the Bibionomorpha or not.

Secondly, the phylogenetic position of non-sciaroid families, such as Bibionidae, Hesperinidae, and Pachyneuridae is still unresolved, in part due to the fact that hesperinid and pachyneurid specimens are rarely collected and poorly represented in collections. Representatives of these three families were included in the morphological analyses by both Fitzgerald (2004) and Amorim & Rindal (2007), which resulted in similar phylogenetic hypotheses, but these hypotheses still need to be tested, especially as the latter study was criticized for fundamental methodological shortcomings (Jaschhof, 2011).

Thirdly, the delimitation of the Sciaroidea is still a controversial issue, especially regarding the inclusion of the Cecidomyiidae and/or Ditomyiidae. Several studies, both molecular (Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann, 2008) and morphological (Fitzgerald, 2004), have been unable to provide support for the monophyly of Sciaroidea (including Ditomyiidae) and most of the studies have not recognized Cecidomyiidae as a part of Sciaroidea.

Fourthly, and perhaps the most puzzling issue of all, is the phylogenetic position and assignment to family of the Sciaroidea incertae sedis, which is closely related to the question of how the family Rangomaramidae should be appropriately defined (cf. Jaschhof & Didham, 2002; Amorim & Rindal, 2007; Jaschhof, 2011). The authors of the present paper do not follow the concept of the Rangomaramidae as proposed by Amorim & Rindal (2007), a practice in common with the most recent Diptera Manuals (Brown et al., 2009; AH Kirk-Spriggs & BJ Sinclair, 2016, unpublished data) as well as papers specifically related to Sciaroidea incertae sedis (e.g., Hippa & Ševčík, 2014). Nevertheless, Amorim & Rindal’s (2007) results and proposals are discussed here when appropriate.

The present paper aims to provide answers, or partial answers, to the four questions outlined above using nuclear and mitochondrial gene markers and taxon sampling designed to address these Bibionomorpha-specific issues.

Material and Methods

Taxon sampling

A total of 94 terminal taxa are included in the dataset (Table 1 and Table S1). The ingroup contains 60 species from all the families traditionally placed in Bibionomorpha sensu lato (except Perissommatidae, Rangomaramidae sensu Jaschhof & Didham, 2002 and Valeseguyidae Amorim & Grimaldi, 2006) including six species of Sciaroidea incertae sedis. As outgroup taxa, we analysed 20 species from 13 families of non-bibionomorph lower Diptera, 13 species from 12 families of Brachycera, and one species of Mecoptera.

Table 1. List of specimens used for DNA extraction, with GenBank accession numbers.

More information about the specimens is listed in the Table S1.

Samples containing these species were collected throughout the world, usually by means of Malaise traps, in the years 2006–2015 (Table S1). Most of the specimens were collected in localities where no field study permission is required. No taxon included in this study is specially protected by law. For the field research in Central Slovakia permission was issued by the Administration of Muránska planina National Park (No. 2011/00619-Ko and OU-BB-OSZP1-2014/13611-Ku). A part of the material examined was collected within the “Thailand Inventory Group for Entomological Research (TIGER) project” supported by the National Research Council of Thailand and the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, Thailand, who gave permission for research and the collection of specimens (see http://sharkeylab.org/tiger/). Two specimens used in the analyses were collected in Kuala Belalong Field Studies Centre, Brunei, in cooperation with the Institute for Biodiversity and Environmental Research, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, who also provided relevant permission (No. UBD-AVC-RI/1.24.1 and BioRIC/HOB/TAD/51-40).

All the specimens used for DNA extraction were identified by the authors (JŠ, SF, MJ), according to the most recent taxonomic literature. The voucher specimens are deposited in the reference collection of the Ševčík Lab, University of Ostrava, Czech Republic (JSL-UOC), with several specimens also deposited in the collection of the Silesian Museum, Opava, Czech Republic (SMOC); see Table S1.

Some sequences, mostly for outgroup taxa, were taken from the GenBank database. We were not able to obtain museum specimens of Rangomaramidae or Perissommatidae for our analyses so any efforts in the future to illuminate the phylogenetic position of these enigmatic groups by molecular approaches will depend on freshly collected material.

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

The material used for DNA analysis was either alcohol-preserved (70% to 99.9% ethanol) or dried and pinned. The DNA was extracted using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) and NucleoSpin Tissue Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) following both manufacturers’ protocols. Individual flies or tissue portions were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), placed in sterile Eppendorf tubes and incubated overnight at 56°C in lysis buffer with proteinase K. PCRs (total volume = 20 µl) were performed using primers for three mitochondrial genes: ribosomal 12S (Cook, Austin & Disney, 2004), ribosomal 16S (Roháček, Tóthová & Vaňhara, 2009), and protein-encoding COI (barcoding region, cf. Folmer et al., 1994); for three nuclear genes: ribosomal 28S (Belshaw et al., 2001) and 18S (Campbell, Ross & Woodward, 1995 or Katana et al., 2001), and two regions of the protein-encoding CAD (Moulton & Wiegmann, 2004), spanning positions 2200–3104 and/or 2977–3668 in the Drosophila melanogaster CAD sequence, see Table S2. We designed one additional primer to amplify the cytochrome oxidase I, mCOIa-R (5′-AAAATAGGGTCTCCTCCTCC-3′). In the case of the taxa Pachyneura fasciata (JSOUT37), Asiorrhina parasiatica (JSB4d), Sciarosoma nigriclava (JSOUT13b), and Aspistes berolinensis (JSOUT43), the 18S rRNA gene was amplified in two overlapping fragments. All amplified products were purified using QIAQuick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Venio, Netherlands), GenElute™ PCR Clean-Up Kit (SIGMA) or Gel/PCR DNA Fragments Extraction Kit (Geneaid, New Taipei City, Taiwan). PCR products of CAD from several samples were extracted from agarose gel and purified with the Gel/PCR DNA Fragments Extraction Kit (Geneaid, New Taipei City, Taiwan).

Sequencing was carried out with BigDye Terminator ver.3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) on an ABI 3100 genetic analysis sequencer (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems, Norwalk, CT, USA), or PCR products were sequenced by Macrogen Europe (Netherlands). All sequences were assembled, manually inspected, and primers trimmed in SEQUENCHER 5.0 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, USA). Sequences used to build an alignment for phylogenetic analysis were deposited in the GenBank database, accession numbers are listed in Table 1.

The identity of all the sequences was confirmed by BLAST similarity searches against NCBI database and double-checked in single gene trees to eliminate possible contaminations or other misleading results. Suspicious-looking sequences, where possible, were sequenced repeatedly from different specimens of the same species as a positive control (e.g., in Asiorrhina parasiatica, Diadocidia globosa, Insulatricha hippai, Lygistorrhina spp., Ohakunea bicolor, Protaxymyia thuja, Sciarosoma nigriclava).

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses

The ribosomal genes 12S, 16S, 18S and 28S were aligned using MAFFT version 7 (Katoh & Standley, 2013) on the MAFFT server (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/). Method L-INS-I, recommended for <200 sequences with one conserved domain and long gaps, was automatically selected by the program according to the alignment sizes. Resulting alignments were visually inspected and manually refined when necessary. The lengths of individual alignments were: 12S = 767 bp, 16 = 399 bp, 18S = 2,554 bp, 28S = 1,399 bp. We also tested some other alignment algorithms (Q-INS-I MAFFT—which considers secondary structure of the molecules; or T-Coffee), but none of them yielded a tree with better resolution.

All unreliably aligned regions were removed in the program GBLOCKS 0.91b (Castresana, 2000) on the Gblocks server (http://molevol.cmima.csic.es/castresana/Gblocks_server.html). Conditions have been set as follows: allowed smaller blocks, allowed gap positions within the final blocks and allowed less strict flanking positions. Sequences of the protein-coding genes COI and CAD were checked based on amino-acid translations and provided indel-free nucleotide alignments. The single-gene alignments were concatenated and the final concatenated alignment was deposited in the Figshare database (https://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.3458082.v1).

We made a comprehensive alignment of 94 terminal taxa comprising almost all major groups of the infraorder Bibionomorpha, as well as a number of outgroup taxa, including several representatives of Brachycera. We selected representatives of diverse lineages and various trophic strategies in each family of the ingroup to make up a balanced dataset. The final data matrix consisted of 5,018 characters: 12S—306 bp, 16S—326 bp, 18S—1,851 bp, 28S—452 bp, CAD—1425, COI—658 bp. Saturation analysis was performed for all six genes using Xia’s test implemented in DAMBE (Xia & Xie, 2001). In the case of the protein coding genes COI and CAD, saturation of third codon positions was tested separately.

Trees were rooted by the representative of the order Mecoptera, which is considered sister group to Diptera (e.g., Misof et al., 2014).

The dataset was analysed using Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) methods. The node support values are given in the form: posterior probability (PP) / bootstrap value (BV). We do not present here any results from the maximum parsimony analysis, because it provided almost no significant support at the higher taxonomic levels (interfamilial relationships), in concordance with theoretical arguments indicating the limited performance of the MP method in molecular phylogenetics (e.g., Gadagkar & Kumar, 2005; Spencer, Susko & Roger, 2005).

To evaluate the best fit model for the BI and ML analyses, the concatenated dataset was partitioned into six sets: six gene regions (12S = 1–306, 16S = 307–632, 18S = 633–2,483, 28S = 2,484–2,935, CAD = 2,936–4,360, COI = 4,361–5,018). Each of the partitions was evaluated in MrModeltest v.2.2 (Nylander, 2004) using both hierarchical likelihood ratio tests (hLRTs) and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). We used model GTR + Γ + I (Rodriguez et al., 1990) for Bayesian inference and GTR + Γ for ML analysis.

The partitioned Bayesian inference of 50 million generations on the concatenated dataset was implemented in MrBayes version 3.2.2 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist, 2001) and carried out on the CIPRES computer cluster (Cyberinfrastructure for Phylogenetic Research; San Diego Supercomputing Center, Miller, Pfeiffer & Schwartz, 2010). Burn-in was set as 30%.

The ML analyses were conducted on the CIPRES computer cluster using RAxML-HPC BlackBox 7.6.3 (Stamatakis, 2006) employing automatic bootstrapping on single gene alignments to check potential conflicting topologies and other artifacts. Subsequently, the same algorithm was applied on the concatenated partitioned dataset.

Phylogenetic trees were visualized using Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) (Letunic & Bork, 2011). The trees presented are Bayesian or ML topologies with node support values from both the analyses.

Results and Discussion

Comparison of the Bayesian and maximum likelihood analyses

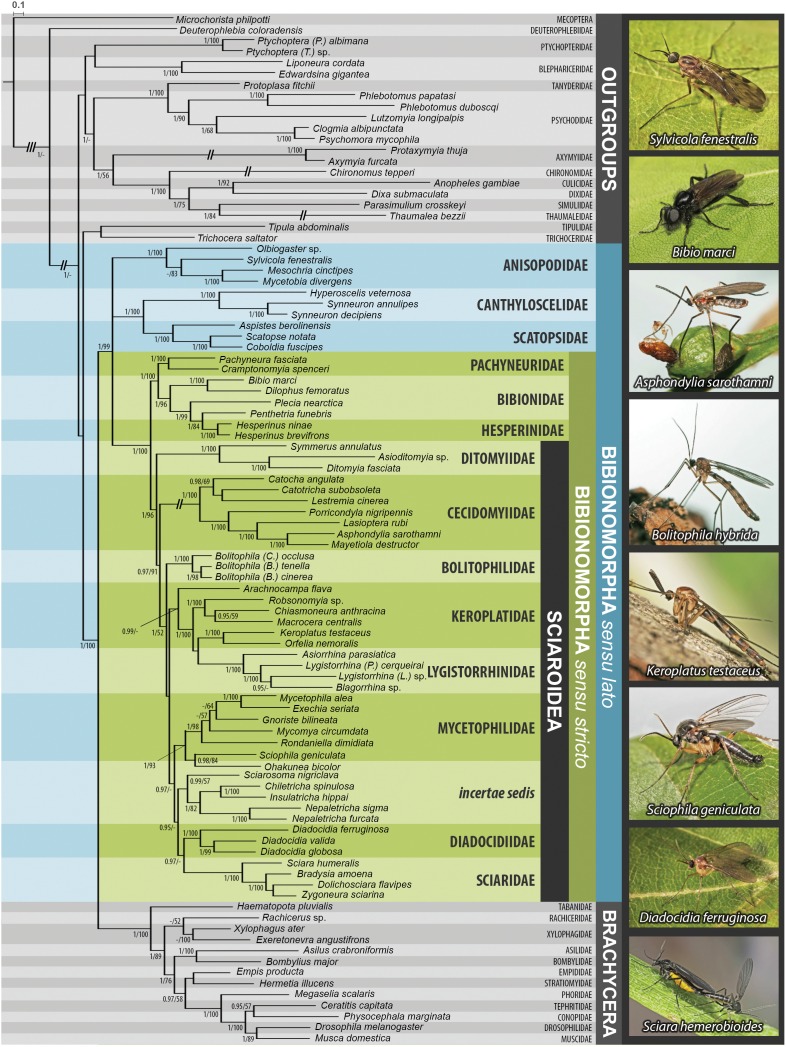

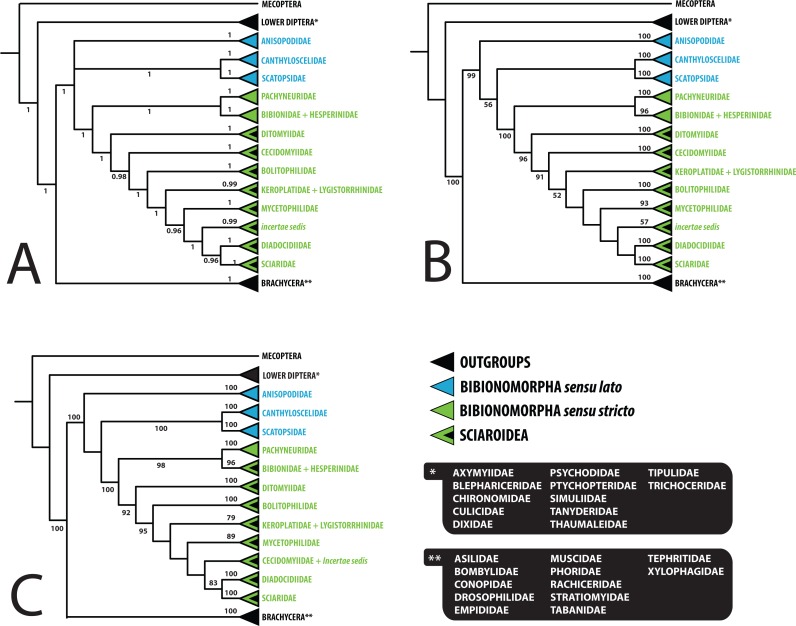

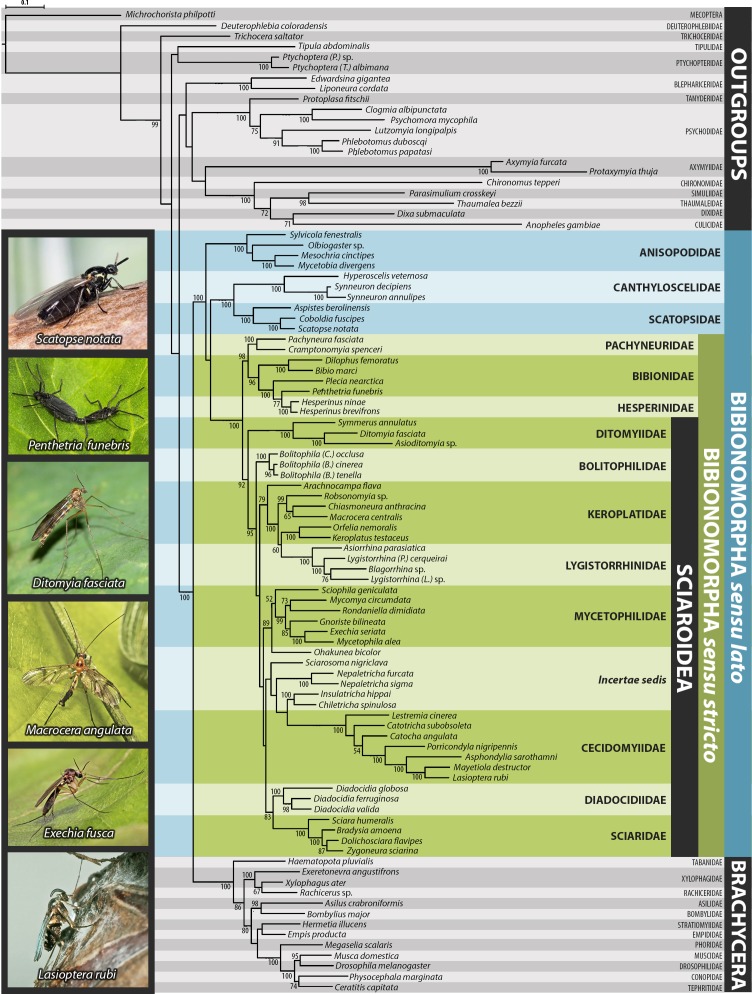

The results based on Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) analyses of the dataset are summarized in Figs. 1–3, Figs. S1 and S2. For BI, standard deviation of split frequencies was in all cases <0.01. The log likelihood value for the best tree of the dataset was −128022.18. Both the model-based methods (BI, ML) yielded mostly congruent nodes, with several exceptions mostly at the family level (Figs. 1–3). Well-supported relationships were consistent across all the trees obtained.

Figure 1. Bayesian hypothesis for relationships among selected taxa of Bibionomorpha based on DNA sequence data (18S, 28S, CAD, 12S, 16S, and COI), 5,018 characters.

Support numbers refer to posterior probability over 0.95/ bootstrap value over 50. The branches marked as “//” have been shortened to its half to fit them into the graphic. All photographs by J Ševčík.

Figure 3. Simplified comparison of relationships among the families of Bibionomorpha.

(A) Bayesian tree; (B) Maximum likelihood tree; (C) Maximum likelihood tree based on dataset without saturated 3rd codon positions. Support numbers refer to posterior probability over 0.95 and bootstrap value over 50, respectively.

Saturation analyses revealed that the phylogenetic markers used in this study show a rather low level of saturation, with the exception of the third positions of the protein coding genes COI and CAD. However, ML phylogenetic analysis based on the dataset with excluded third codon positions provided a tree with very similar topology (cf. Figs. 1 and 2) in comparison with the original tree, with small differences only within several family-level clades and also slight changes in node support values. These minor differences are discussed below when relevant.

Figure 2. Maximum likelihood hypothesis for relationships among selected taxa of Bibionomorpha based on dataset without 3rd codon positions.

Support numbers refer to bootstrap values over 50. Photographs by J Roháček (Scatopse notata) and J Ševčík.

Delimitation, monophyly and affiliation of Bibionomorpha

The monophyly of Bibionomorpha sensu stricto (containing Sciaroidea, Bibionidae, Hesperinidae, and Pachyneuridae) was established with high support (PP = 1.00/BV = 100) in both the model-based analyses (see Figs. 1–3, Figs. S1 and S2). The monophyly of Bibionomorpha sensu lato (containing Bibionomorpha s. str. plus Anisopodidae sensu lato, Canthyloscelidae, and Scatopsidae, 1.00/99) was also established. These findings are consistent with results from the previous molecular and morphological studies, which usually found Bibionomorpha (in various concepts) to be monophyletic (e.g., Hennig, 1954; Oosterbroek & Courtney, 1995; Amorim & Yeates, 2006; Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann, 2008; Wiegmann et al., 2011). Amorim & Yeates (2006) even suggested raising the Bibionomorpha to the rank of suborder.

The present study shows Bibionomorpha sensu lato to be sister group to Brachycera (1.00/99), which is congruent with results from the molecular studies by both Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann (2008) and Wiegmann et al. (2011). Hennig (1973), who came to the same result through morphological study, referred to two synapomorphies supporting this relationship: the conspicuous enlargement of the second latero-tergite and the undivided postphragma of the thorax. Fitzgerald (2004) considered the structure of the parameres (presence of a dorsal sclerite and ventrolateral apodemes) as synapormorphies of this taxon and Michelsen (1996) even introduced a new taxon, Neodiptera, for Bibionomorpha sensu lato + Brachycera based on several cervical and prothoracic skeleto-muscular characters as synapomorphies.

On the other hand, the Bayesian tree by Beckenbach (2012), based on the complete mitochondrial genome of 24 species of Diptera, revealed Anisopodidae + Tanyderidae to be the sister group to Brachycera, but with relatively low support. The morphological study by Oosterbroek & Courtney (1995) considered only Anisopodidae (rather isolated in their tree from the rest of Bibionomorpha) as the sister group to Brachycera, with Anisopodidae + Brachycera being the sister group to the clade containing Tipulidae and Trichoceridae. Their Bibionomorpha included the family Axymyiidae and formed a sister clade to the whole “higher Nematocera and Brachycera” (Perissommatidae, Scatopsidae, Synneuridae, Psychodidae, Tipulidae, Trichoceridae, Anisopodidae, and Brachycera).

Within the Bibionomorpha sensu lato, all the major lineages (i.e., Anisopodoidea, Scatopsoidea, Bibionoidea, and Sciaroidea) were highly supported as monophyletic groups in both model-based analyses (1.00/100, 1.00/100, 1.00/100, and 1.00/96, respectively, see Figs. 1–3).

Delimitation and monophyly of Sciaroidea

The monophyly of fungus gnats, Sciaroidea (= Mycetophiliformia of Amorim & Rindal, 2007), was confirmed here with high support (1.00/96), with both Cecidomyiidae and Ditomyiidae being integral parts of Sciaroidea. Previous phylogenetic studies based on morphology mostly considered Cecidomyiidae as the sister group to Sciaroidea (cf. Matile, 1990; Matile, 1997; Søli, 1997; Chandler, 2002; Hippa & Vilkamaa, 2005; Hippa & Vilkamaa, 2006). Amorim & Rindal (2007) used the name Mycetophiliformia for the large assemblage of taxa grouped into 5 superfamilies: Cecidomyioidea (containing Cecidomyiidae), Sciaroidea (containing only Sciaridae), Rangomaramoidea (Rangomaramidae in a broad sense, including most of the incertae sedis genera), Keroplatoidea (Ditomyiidae, Bolitophilidae, Diadocidiidae, Keroplatidae) and Mycetophiloidea (Lygistorrhinidae, Mycetophilidae). The trees they presented differ from our results in many ways but in all of them Cecidomyiidae form a sister branch to the rest of their Mycetophiliformia. Oosterbroek & Courtney (1995) considered Cecidomyiidae + Sciaridae as the sister group to Mycetophilidae sensu lato.

It is beyond the scope of this study to discuss the details of all these morphological analyses, but we think that a general failure of the past is underappreciation of the relevance of Catotrichinae, which according to the prevailing opinion (cf. Gagné & Jaschhof, 2014) are sister group to all the other Cecidomyiidae. The subfamily Catotrichinae contains only a few species, which are seldom treated in publications (most recently by Jaschhof & Jaschhof (2008), so too late to be taken in consideration by the studies referred to above). Even more important, hardly any dipterist has seen specimens of Catotrichinae so as to appreciate their remarkable resemblance with fungus gnats rather than with other gall midges. As another problem, knowledge of Cecidomyiidae morphology is evidently often too vague to interpret characters and character states correctly (cf. Hippa & Vilkamaa, 2005; Amorim & Rindal, 2007).

The molecular analysis by Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann (2008) recovered a paraphyletic Sciaroidea, with Ditomyiidae excluded, and with moderate support 0.92/76 for a clade consisting of Ditomyiidae + (Bibionidae + Pachyneuridae). The incongruence between the results of Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann (2008) and our results might possibly be explained by the more extensive taxon sampling (almost three times as many species of Bibionomorpha sensu lato included) in the present study.

Monophyly and interrelationships of bibionomorph families

Although the sampling was not designed to thoroughly answer questions on the monophyly of particular families, most of the previously recognized families of Bibionomorpha were monophyletic with high support in all the analyses performed (Figs. 1–3, Figs. S1 and S2). The paraphyly of Keroplatidae is discussed below. The paraphyly of Mycetophilidae (with respect to Ohakunea Edwards, a genus usually regarded as unplaced to family) as suggested in Fig. 1 is surprising and is also commented on below.

The position of Anisopodidae sensu lato and Scatopsoidea (Scatopsidae + Canthyloscelidae) within Bibionomorpha sensu lato was not resolved in the Bayesian tree (Fig. 1). However, in the ML trees (Fig. 2, Figs. S1 and S2), Scatopsoidea was found to be the sister group to Bibionomorpha, with Anisopodidae being sister group to Bibionomorpha sensu stricto + Scatopsoidea, in concordance with previous major studies (Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann, 2008; Wiegmann et al., 2011; Lambkin et al., 2013).

With respect to the position of Axymyiidae, our analysis produced a surprising result. While some previous studies placed Axymyiidae as the sister group to Bibionomorpha sensu stricto (e.g., Oosterbroek & Courtney, 1995; Wiegmann et al., 2011) or in a clade together with Pachyneuridae and Perissommatidae (e.g., Hennig, 1973; Amorim, 1993), our study grouped Axymyiidae with Culicomorpha, though with only moderate support (1.00/56). To exclude the possible long-branch attraction artifact in this case, we tested the ML topology after removal of the long-branch forming Culicomorpha clade. The resulting topology confirmed the position of Axymyiidae within the outgroup taxa. A similar topology was introduced by Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann (2008), with Culicomorpha being the sister group to Axymyiidae + Nymphomyiidae. The morphological study by Fitzgerald (2004) also found Axymyiidae neither within nor sister group to Bibionomorpha. While several studies seem to indicate that Axymyiidae may not belong within, or as sister group to, Bibionomorpha, the phylogenetic position of Axymyiidae clearly requires further study.

As regards the families of Sciaroidea, BV supports from our ML analysis are generally rather low to infer interfamilial relationships, but PP supports for our Bayesian analysis provide better resolution. Concerning the relationships between families within Sciaroidea, the only well supported node in both the model-based analyses (1.00/100) is Keroplatidae, excluding Arachnocampa Edwards, 1924, and containing Keroplatinae, Macrocerinae and Lygistorrhinidae; see Figs. 1 and 2 and ‘Paraphyly of Keroplatidae’.

Ditomyiidae was shown to branch basally from the rest of Sciaroidea, with high support in both the analyses (1.00/96). This result is supported by most previous studies based on morphology (Zaitzev, 1983; Zaitzev, 1984; Wood & Borkent, 1989; Matile, 1990; Matile, 1997; Hippa & Vilkamaa, 2006), pointing to several primitive characters of ditomyiid larvae, such as the presence of the eighth abdominal spiracle and the structure of the mouthparts.

The family Cecidomyiidae is supported as the sister group to the remainder of Sciaroidea (excluding Ditomyiidae) in both the Bayesian and ML analyses (0.97/91). We consider it remarkable that our analyses showed Cecidomyiidae to be firmly nested within the fungus gnats, as discussed above. Interestingly, in the tree based on 18S only, as well as in the tree based on ribosomal genes only, Cecidomyiidae appeared in the clade with two incertae sedis genera (Chiletricha Chandler + Insulatricha Jaschhof) with high support in the ML analysis (BV = 100), indicating possible affinities of these groups. Also, in the ML tree based on the dataset with the saturated third codon positions removed (Fig. 2), Cecidomyiidae and the incertae sedis merged into one clade (albeit poorly supported). It will be very interesting to see how the topology obtained here will change when other unplaced Sciaroidea, as well as Rangomarama (discussed by Jaschhof & Didham (2002) to be the sister group of Cecidomyiidae), can be added to the dataset. The topologies proposed by Matile (1990) and Matile (1997) differ from our results mainly in the positions of Ditomyiidae, Diadocidiidae and Cecidomyiidae. Some previous authors (e.g., Oosterbroek & Courtney, 1995; Wood & Borkent, 1989) considered Cecidomyiidae as a sister group to Sciaridae. This view is not supported by our analyses.

Bolitophilidae is supported as the sister group to the other Sciaroidea (excluding Ditomyiidae and Cecidomyiidae), but with high support only in our Bayesian analysis (1.00/52). This clade was also supported as monophyletic by a number of larval synapomorphies by Fitzgerald (2004: 42) though larval stages of many taxa remain unknown and were therefore not included. Bolitophilidae is a family poorly represented in previous phylogenetic studies, especially molecular ones. As an exception, Wiegmann et al. (2011) included one species of Bolitophila Meigen in their dataset. Their analysis resulted in the sister grouping of Bolitophilidae and Keroplatidae, a topology that differs from ours, indicating the need of further studies into this issue in the future. One of the possible reasons for this discrepancy might be the fact that Bolitophila sp. was represented in their dataset by only three gene markers (28S,TPI, AATS1) and the whole family Keroplatidae only by one rather atypical member, Arachnocampa flava Harrison, 1966. The possible relationship of Arachnocampa to Bolitophilidae is an interesting hypothesis itself, though beyond the scope of this paper, considering the fact that the type species of the genus, Arachnocampa luminosa (Skuse, 1891) was initially described in Bolitophila and removed from this genus subsequently by Edwards (1924), who also discussed similarities and differences of the two genera.

The present study corresponds with an earlier one by Ševčík et al. (2014) which suggested Sciaridae to be the closest relative of Diadocidiidae, although with relatively high support only in Bayesian analysis (0.96/-). However, this clade is better supported (1/74) in the tree without the incertae sedis genera (Fig. S1) and in the ML tree based on the dataset without saturated third codon positions (Fig. 2).

Likewise, the topology (Diadocidiidae + Sciaridae) + Sciaroidea incertae sedis is moderately supported but only in our Bayesian analysis (PP = 0.95). There is slightly better support (1/52) for the sister grouping found for the entire latter clade + Mycetophilidae including Ohakunea (Fig. 1).

As revealed in this study, the relationships among the families of Sciaroidea still require further testing with the addition of more incertae sedis taxa and with a more extensive gene sampling (e.g., from next-generation sequencing). However, judging from the short branches in the family-level clades, it can be concluded that these taxa underwent very rapid radiation leaving low phylogenetic signal, which will be difficult to resolve. Another serious limitation will always be obtaining fresh specimens with a sufficient amount of DNA/RNA for several key taxa that are extremely rare.

Paraphyly of Keroplatidae

The family Keroplatidae is paraphyletic with respect to Lygistorrhinidae in this study in both BI and ML analyses (the node support for the entire clade is 0.99/47, see Fig. 1) and also in the ML analysis based on the dataset without the saturated third codon positions (Fig. 2). The close relationship of Keroplatidae and Lygistorrhinidae was also indicated in most of the single-gene trees, being best supported in the CAD-based tree.

The sister clade to Arachnocampa, containing all the remaining taxa of Keroplatidae and Lygistorrhinidae, is even better supported (1.00/100). Within the latter clade, the genera of Lygistorrhinidae form a sister group to Keroplatinae, but with low support (0.65/46), see also below (‘Keroplatidae and Lygistorrhinidae’).

Tuomikoski (1966) was the first to hypothesize a possible relationship between Lygistorrhinidae and Keroplatidae, indicating that Lygistorrhina Skuse, 1890 most probably represents only a specialized group within Keroplatidae. He argued that the reduced wing venation in this genus may be misleading and that the thoracic structure, male terminalia, and other features of Lygistorrhina are very similar to those of Fenderomyia Shaw, 1948 and other taxa of Macrocerinae. However, his views were criticized by Thompson (1975), arguing that some of the characters shared by both groups (e.g., simple type of the male terminalia) are actually symplesiomorphies. Subsequent studies based on morphology have usually placed Lygistorrhinidae close to Mycetophilidae, and Keroplatidae close to Diadocidiidae (Matile, 1990; Matile, 1997; Chandler, 2002; Hippa & Vilkamaa, 2006; Amorim & Rindal, 2007). On the contrary, the close relationship between Lygistorrhinidae and Keroplatidae was indicated by three independent previous molecular studies (Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann, 2008; Rindal, Søli & Bachmann, 2009; Ševčík et al., 2014) and it has also recently been suggested by Kallweit (2014) based on morphology.

The results of our analyses thus strongly support the inclusion of Lygistorrhinidae in the family Keroplatidae, probably best treated as a subfamily of the latter. The position of Arachnocampa, as discussed above (in ‘Monophyly and interrelationships of bibionomorph families’), requires further study, which is beyond the scope of this paper.

Position of Sciaroidea incertae sedis

The genera Chiletricha, Insulatricha, Nepaletricha Chandler, 2002, Ohakunea and Sciarosoma Chandler, 2002, currently not assigned to a family, have usually been treated within the Heterotricha group (Chandler, 2002) or Sciaroidea incertae sedis (Jaschhof, 2011). Notable exceptions are Hippa & Vilkamaa (2005), who hypothesized Sciarosoma (in a subfamily of its own, Sciarosominae) as belonging to the Sciaridae, and Amorim & Rindal (2007), who placed all these genera except Sciarosoma in the broadly defined family Rangomaramidae (Sciarosoma was left unplaced to family within their Mycetophiliformia = Sciaroidea). Both these studies were challenged in the past (Jaschhof et al., 2006; Jaschhof, 2011, respectively). Most recently, Hippa & Ševčík (2014) discussed possible inclusion of Nepaletricha and related genera in the fossil family Antefungivoridae, based on the similarity of the wing venation.

These five genera are the only taxa from this enigmatic grouping with molecular data currently available. Our analyses showed Ohakunea to be only distantly related to the other four genera (Fig. 1), even though its position within the Mycetophilidae came as a surprise (see also ‘Mycetophilidae’). The other enigmatic genera are united in a single moderately supported clade (0.99/57) and as sister group to the clade Diadocidiidae + Sciaridae, but with lower support (0.95/-). Within this clade, Sciarosoma is branching basally to the well supported (1.00/82) clade of Nepaletricha and Chiletricha + Insulatricha.

As long as the majority of incertae sedis remain unstudied, we think it premature to attach too much importance to the specific positions of the enigmatic genera in the topology presented here, but the well-supported monophyly of (Chiletricha + Insulatricha) + Nepaletricha could be interpreted as giving support to the Chiletrichinae of Amorim & Rindal (2007).

When we excluded all the incertae sedis genera from the dataset (Fig. S1), the support values for the clade Diadocidiidae + Sciaridae increased to 1.00/78 and those for the Keroplatidae clade (including Arachnocampa and Lygistorrhinidae) increased to 1.00/60. This manipulation shows how important it is to include as many of the incertae sedis genera as possible in future molecular analyses.

Relationships within particular families

Anisopodidae

The monophyly of Anisopodidae sensu lato is well supported (1.00/100) in all the analyses (Figs. 1 and 2), as well as the sister relationship of Mycetobia Meigen, 1818 and Mesochria Enderlein, 1910. The topology Olbiogaster + (Sylvicola + Mycetobia) in our analyses is in concordance with the hypothesis based on morphology given by Amorim & Tozoni (1994) while Michelsen (1999) suggested a different relationship, Sylvicola Harris, 1780 + (Olbiogaster Osten-Sacken, 1886 + Mycetobiidae). The latter topology was produced by our datasets with the third codon positions removed (Fig. 2) but with very low support for the clade (Olbiogaster + Mycetobiinae). A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of this group, based on better taxon sampling, is needed to elucidate these relationships.

Bibionidae and Pachyneuridae

The monophyly of Bibionidae sensu lato (Bibionidae sensu stricto + Hesperinidae) was established with high support (1.00/96). The clade containing the genera Bibio Geoffroy, 1762 and Dilophus Meigen, 1803 (Bibioninae) is sister group to the clade Plecia Wiedemann, 1828 + (Penthetria Meigen, 1803 + Hesperinus Walker, 1848), with all nodes well supported (Fig. 1). This topology suggests that either Hesperinus should not be classified in the separate family Hesperinidae because it would render the rest of Bibionidae paraphyletic or, Bibioninae, Plecia, Penthetria, and Hesperinus each need to be treated as distinct families. The position of Hesperinus within (rather than sister group to) Bibionidae is a novel hypothesis (DNA sequences for Hesperinus are published here for the first time) and it conflicts with several previous hypotheses that place Hesperinus as sister group to the remaining Bibionidae (Blaschke-Berthold, 1994; Fitzgerald, 2004; Pinto & Amorim, 2000). The topology found here requires a number of morphological characters that have been found to support bibionids exclusive of Hesperinus (e.g., male eye holoptic, male antennal flagellomeres compressed, larva with fleshy tubercles, larval intersegmental fissures separating abdominal segments seven and eight unaligned laterally, and larval abdominal segment three with three pseudosegments, see Fitzgerald, 2004) to be independently derived multiple times or derived once and then secondarily lost in Hesperinus. Further studies to elucidate these issues are thus warranted. Congruent with previous morphological studies focused on bibionids (Fitzgerald, 2004; Pinto & Amorim, 2000) the clade Plecia + Penthetria was not supported in this analysis thereby further discouraging the recognition of this clade which is commonly classified as Pleciidae or Pleciinae.

Bibionoidea (Bibionidae sensu lato + Pachyneuridae) was strongly supported as a monophyletic group in our analyses (1.00/100) echoing the findings of several earlier morphological (Blaschke-Berthold, 1994; Fitzgerald, 2004) and molecular studies (Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann, 2008; Wiegmann et al., 2011). Due to the rarity of pachyneurids for study, the monophyly of the family Pachyneuridae sensu lato (Pachyneura Zetterstedt, 1838 + Cramptonomyiinae) has only rarely been assessed (Amorim, 1993; Blaschke-Berthold, 1994; Fitzgerald, 2004) and monophyly of the group has never been tested using molecular characters (Pachyneura is here sequenced for the first time). Fitzgerald (2004: 41) found seven unambiguous characters supporting monophyly of Pachyneuridae s.l., including one adult and three larval characters unique to the family. The present study also found strong support for the monophyly of Pachyneuridae s.l. thereby not supporting the previous hypothesis based on wing venation (Amorim, 1993) that considers Pachyneuridae s.l. to be paraphyletic and treats the genus Pachyneura in Axymyiomorpha with Axymyiidae.

Cecidomyiidae

The monophyly of Cecidomyiidae is here fully supported (1.00/100) in all the analyses (Figs. 1–3, Figs. S1 and S2). All the major lineages (subfamilies) recognised within the family except Winnertziinae are represented in our dataset. The clade Catocha Haliday, 1833 + (Catotricha Edwards, 1938 + Lestremia Macquart, 1826) was found to be the sister branch to the other Cecidomyiidae, which is remarkable insofar as solely Catotrichinae are usually placed at the base of the family (see above). The sister branch is formed by Porricondyla Rondani, 1840 + (Asphondylia Loew, 1850 + (Lasioptera Meigen, 1818 + Mayetiola Kieffer, 1896)), which is congruent with data based on morphology (Gagné, 1989; Jaschhof, 2001; Jaschhof & Jaschhof, 2009; Jaschhof & Jaschhof, 2013).

A molecular phylogeny of Cecidomyiidae, with taxon sampling that better represents the full range of this diverse family, is in preparation (T Sikora et al., 2016, unpublished data).

Keroplatidae and Lygistorrhinidae

The paraphyly of Keroplatidae with respect to Lygistorrhinidae was discussed above. Within the family Lygistorrhinidae, Asiorrhina Blagoderov, Hippa & Ševčík (2009) is sister group to the other Lygistorrhinidae (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1, 1.00/100), similar to the phylogenies proposed by Blagoderov, Hippa & Ševčík (2009), Hippa, Mattsson & Vilkamaa (2005) and Ševčík et al. (2014).

Within the Keroplatidae, Arachnocampa is sister group to the rest of Keroplatidae and Lygistorrhinidae (but see the discussion above, in ‘Monophyly and interrelationships of bibionomorph families’). Two major subclades, corresponding to the subfamilies of Matile (1990), can also be distinguished: Keroplatinae and Macrocerinae. Both of these groups were well supported (Fig. 1, 1.00/100, resp. 1.00/100) but the sister group relationship between Keroplatinae and Lygistorrhinidae is only poorly supported (0.65/46). The exact position of the subfamily Sciarokeroplatinae (see Papp & Ševčík, 2005) could not be ascertained by molecular methods because no fresh specimens of its only genus, Sciarokeroplatus Papp & Ševčík, 2005, have been available to study.

Mycetophilidae

The monophyly of Mycetophilidae is well supported (1.00/94), but only in the tree without the incertae sedis genera (Fig. S1). In the tree in Fig. 1, surprisingly, Ohakunea nested within the mycetophilid clade (1.00/93) as sister branch to Sciophila Meigen, 1818 (0.98/84). Its position clearly demonstrates the paraphyly of the incertae sedis genera but the possible relationship with Sciophila (or other mycetophilid genera) is difficult to substantiate by morphological characters (except the macrotrichia on the wing membrane and other plesiomorphic features). Considering that the known distribution of Ohakunea is restricted to the Australasian and Neotropical regions, it was concluded that it may represent an ancient lineage of sciaroids that evolved in Gondwanaland (Jaschhof & Hippa, 2003). The surprising position of Ohakunea within the Mycetophilidae clade may also be attributed to the relatively low taxon sampling of Mycetophilidae in this study; with the addition of more genera, its position could change. It is worth mentioning in this context that in the tree based on the dataset without the saturated third codon positions (Fig. 2), Ohakunea appeared as sister group to the family Mycetophilidae. Clearly, this issue requires a separate study.

Within the family Mycetophilidae, Sciophilinae (represented here by its type genus Sciophila) is usually considered to show plesiomorphic character states while subfamily Mycetophilinae, here represented by the genera Exechia Winnertz, 1863 and Mycetophila Meigen, 1803, is usually considered a more advanced group (e.g., Søli, 1997), sharing several apomorphic character states (e.g., wing microtrichia arranged in regular rows, structure of proepimeron and epimeron, and strict endomycophagy of the larvae). This view is also supported by our data (Figs. 1, 2 and Figs. S1, S2).

Sciaridae

A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of this family was recently presented by Shin et al. (2013). The sampling of Sciaridae in our study is necessarily limited to keep the numbers of terminal taxa in proportion for particular families, but the relationships among the genera included in our dataset principally agree with the topology presented in the latter study (Figs. 1, 2 and Figs. S1, S2).

Comments on the selection of molecular markers and perspectives for the future

This study represents the first molecular phylogeny of Bibionomorpha based on a comprehensive taxon sampling. We tried to use easily-amplifiable, traditional gene markers because we were strongly limited by the scarcity of many taxa included in the dataset (and therefore had a shortage of DNA). For the following rare genus-group taxa we publish the first molecular data at all: all the Sciaroidea incertae sedis included (except Nepaletricha), Asioditomyia Saigusa, 1973, Blagorrhina Hippa, Mattison & Vilkamaa, 2009, Catocha, Catotricha, Chiasmoneura Meijere, 1913, Hesperinus, Hyperoscellis Hardy & Nagatomi, 1960, Mesochria, Pachyneura, Protaxymyia Mamaev & Krivosheina, 1966, Robsonomyia Matile & Vockeroth, 1980, Rutylapa Edwards, 1929—and for some clades we thus present the first phylogenetic hypotheses based on molecular data.

We also succeeded in incorporating two regions (of total length more than 1,400 bp) of the protein-coding nuclear gene CAD, which is recommended for use in reconstruction of Diptera phylogeny by Moulton & Wiegmann (2004) and subsequent authors. The amplification of the various fragments of this gene proved to be much more difficult than in traditional markers, so the inclusion of more protein-coding nuclear genes has not been possible with current material, which includes many rare species, available as only one or two specimens, usually collected several years ago. As soon as more fresh material (especially of Sciaroidea incertae sedis) is available for next-gen sequencing, which may take several years or more, it should be possible to design specific primers for Sciaroidea and amplify the supposedly more informative protein-coding nuclear genes, such as MCS and MAC (see Winkler et al., 2015). Our attempts to amplify MCS and MAC markers from most of the specimens of Bibionomorpha using the primers designed for other groups of Diptera failed.

Despite these shortcomings, we consider it important to publish a tree with lower resolution in a few branches because it contributes to our understanding of the performance of these traditional markers across the various taxa of Bibionomorpha, especially when they provide sufficient resolution for most other relationships within the group. Our dataset is largely based (74% of base pairs) on the very little saturated nuclear 18S, 28S and CAD genes, more suitable for deeper relationships, in combination with three short mitochondrial regions included to improve the resolution of terminal branches, and in the case of COI also to enrich the DNA barcode database.

Conclusions

-

1.

Monophyly of Bibionomorpha is supported in both the strict sense (Sciaroidea + Bibionoidea) and the broad sense (Bibionomorpha sensu strico + Anisopodoidea + Scatopsoidea). Axymyiidae is not resolved as part of, or as the sister group to, Bibionomorpha.

-

2.

The monophyly of the groups Bibionoidea (Bibionidae sensu lato + Pachyneuridae sensu lato), Bibionidae sensu lato (Bibionidae sensu stricto + Hesperinidae), and Pachyneuridae (Pachyneura + Cramptonomyiinae) were all established with high support in all the analyses. Based on the topology recovered here, treating Hesperinus as the distinct family Hesperinidae would render the rest of Bibionidae paraphyletic. Diverging from previous hypotheses that place Hesperinus as the sister group to the remaining bibionids, the position of Hesperinus in this study is a novel hypothesis that requires further testing. As in previous studies, Pleciidae or Pleciinae (Plecia + Penthetria) was not supported as a monophyletic group and its usage should be discontinued.

-

3.

The major lineages of Bibionomorpha sensu lato (Sciaroidea, Bibionoidea, Anisopodoidea, and Scatopsoidea) are well supported as monophyletic groups and all included families are supported as monophyletic with the exception of Keroplatidae and Bibionidae sensu lato. Both Cecidomyiidae and Ditomyiidae were recovered in model-based analyses as a part of Sciaroidea with high support. All the other families previously placed in Sciaroidea were confirmed to belong to this monophyletic group. The Keroplatidae clade (including Lygistorrhinidae) is well supported, but not so much with Arachnocampa. In most other cases support is too low to confidently resolve family level relationships within Sciaroidea.

-

4.

The five genera of Sciaroidea incertae sedis that were included in this analysis do not constitute a monophyletic group thereby not supporting an expanded concept of Rangomaramidae (Amorim & Rindal, 2007) but further studies with more taxa included are much needed.

Supplemental Information

Support numbers refer to posterior probability over 0.95/ bootstrap value over 50/ jackknife value over 50. The branches marked as “//” have been shortened to its half to fit them into the graphic.

Support numbers refer to bootstrap value over 50. The branches marked as “//” have been shortened to its half to fit them into the graphic.

Acknowledgments

L Dembický (Brno, Czech Republic), PH Kerr (Sacramento, USA), O Kurina (Tartu, Estonia), J Roháček (Opava, Czech Republic) and J Salmela (Rovaniemi, Finland) kindly provided specimens for this study. We also thank M Eliáš and V Yurchenko (University of Ostrava, Czech Republic) for useful discussions about the molecular methods and tree topologies and the latter also for critical reading of an earlier version of this manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study was mostly supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports Life of the Czech Republic through the Institutional Support of research organisation (University of Ostrava). Various parts of our research activities were supported by the SGS21/PřF/2013, SGS28/PřF/2014 and SGS28/PřF/2015 projects of the University of Ostrava and by the projects CZ.1.05/2.1.00/03.0100 (IET) financed by the Structural Funds of the European Union and LO1208 of the National Feasibility Programme I of the Czech Republic. A part of the material examined was collected within the “Thailand Inventory Group for Entomological Research (TIGER) project” funded by US National Science Foundation grant DEB-0542864 to M Sharkey and B Brown, and supported by the National Research Council of Thailand and the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, Thailand, who gave permission for research and the collection of specimens. M Jaschhof is funded by the Swedish Species Information Centre within the framework of the Swedish Taxonomy Initiative (dha 2014-150 4.3). Sponsorship was provided by the Willi Hennig Society that made TNT v.2.0 available. CIPRES, an NSF-funded resource for phyloinformatics and computational phylogenetics, was used to conduct some of the analyses. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Jan Ševčík conceived and designed the experiments, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper, collected and identified specimens.

David Kaspřák performed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Michal Mantič performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Scott Fitzgerald and Mathias Jaschhof wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper, collected and identified specimens.

Tereza Ševčíková analyzed the data, reviewed drafts of the paper, supervised the lab procedures and bioinformatics work.

Andrea Tóthová conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, reviewed drafts of the paper, performed the Bayesian analyses.

Field Study Permissions

The following information was supplied relating to field study approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

Most of the specimens were collected in localities where no field study permission is required. No taxon included in this study is specially protected by law. For the field research in Central Slovakia permission was issued by the Administration of Muránska planina National Park (No. 2011/00619-Ko and OU-BB-OSZP1-2014/13611-Ku). A part of the material examined was collected within the “Thailand Inventory Group for Entomological Research (TIGER) project” supported by the National Research Council of Thailand and the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, Thailand, who gave permission for research and the collection of specimens (see http://sharkeylab.org/tiger/). Two specimens used in the analyses were collected in Kuala Belalong Field Studies Centre, Brunei, in cooperation with the Institute for Biodiversity and Environmental Research, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, who also provided relevant permission (No. UBD-AVC-RI/1.24.1 and BioRIC/HOB/TAD/51-40).

DNA Deposition

The following information was supplied regarding the deposition of DNA sequences:

Sequences have been submitted to the GenBank database under the accession numbers listed in Table 1. Edited sequence alignments used for phylogenetic analyses are available at https://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.3458082.v1.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Kaspřák, David (2016): Bibionomorpha alignments. Figshare:

References

- Amorim (1993).Amorim DS. A phylogenetic analysis of the basal groups of Bibionomorpha, with a critical reanalysis of the wing vein homology. Revista Brasileira de Biologia. 1993;52:379–399. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim & Grimaldi (2006).Amorim DS, Grimaldi DA. Valeseguyidae, a new family of Diptera in the Scatopsoidea, with a new genus in Cretaceous amber from Myanmar. Systematic Entomology. 2006;31:508–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2006.00326.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amorim & Rindal (2007).Amorim DS, Rindal E. Phylogeny of the Mycetophiliformia, with proposal of the subfamilies Heterotrichinae, Ohakuneinae, and Chiletrichinae for the Rangomaramidae (Diptera, Bibionomorpha) Zootaxa. 2007;1535:1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim & Tozoni (1994).Amorim DS, Tozoni SHS. Phylogenetic and biogeographic analysis of the Anisopodoidea (Diptera, Bibionomorpha), with an area cladogram for intercontinental relationships. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia. 1994;38:517–543. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim & Yeates (2006).Amorim DS, Yeates D. Pesky gnats: ridding dipteran classification of the “Nematocera”. Studia Dipterologica. 2006;13:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Beckenbach (2012).Beckenbach AT. Mitochondrial genome sequences of Nematocera (lower Diptera): evidence of rearrangement following a complete genome duplication in a winter crane fly. Genome Biology and Evolution. 2012;4:89–101. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belshaw et al. (2001).Belshaw R, Lopez-Vaamonde C, Degerli N, Quicke DLJ. Paraphyletic taxa and taxonomic chaining: evaluating the classification of braconine wasps (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) using 28S D2-3 rDNA sequences and morphological characters. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2001;73:411–424. doi: 10.1006/bijl.2001.0539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertone, Courtney & Wiegmann (2008).Bertone MA, Courtney GW, Wiegmann BM. Phylogenetics and temporal diversification of the earliest true flies (Insecta: Diptera) based on multiple nuclear genes. Systematic Entomology. 2008;33:668–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2008.00437.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blagoderov & Grimaldi (2004).Blagoderov V, Grimaldi D. Fossil Sciaroidea (Diptera) in Cretaceous ambers, exclusive of Cecidomyiidae, Sciaridae, and Keroplatidae. American Museum Novitates. 2004;3433:1–76. [Google Scholar]

- Blagoderov, Hippa & Ševčík (2009).Blagoderov V, Hippa H, Ševčík J. Asiorrhina, a new Oriental genus of Lygistorrhinidae (Diptera: Sciaroidea) and its phylogenetic position. Zootaxa. 2009;2295:31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke-Berthold (1994).Blaschke-Berthold U. Bonner zoologische Monographien 34. Zoologisches Forschungsinstitut und Museum Alexander Koenig; Bonn: 1994. Anatomie und Phylogenie der Bibionomorpha (Insecta: Diptera) [Google Scholar]

- Brown et al. (2009).Brown BV, Borkent A, Cumming JM, Wood DM, Woodley NE, Zumbado M. Manual of central american diptera: volume 1. National Research Council Research Press; Ottawa, Ontario: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Ross & Woodward (1995).Campbell BC, Ross GF, Woodward TE. Paraphyly of Homoptera and Auchenorrhyncha inferred from 18S rDNA nucleotide sequence. Systematic Entomology. 1995;20:175–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.1995.tb00090.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castresana (2000).Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2000;17:540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler (2002).Chandler P. Heterotricha Loew and allied genera (Diptera: Sciaroidea): offshoots of the stem group of Mycetophilidae and/or Sciaridae? Annales de la Société Entomologique de France (Nouvelle série) 2002;38:101–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Austin & Disney (2004).Cook CE, Austin JJ, Disney RHL. A mitochondrial 12S and 16S rRNA phylogeny of critical genera of Phoridae (Diptera) and related families of Aschiza. Zootaxa. 2004;593:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards (1924).Edwards FW. A note on the “New Zealand glow-worm” (Diptera, Mycetophilidae) Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 1924;14:175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Evenhuis (1994).Evenhuis NL. Catalogue of the fossil flies of the world (Insecta: Diptera) Backhuys Publishers; Leiden: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald (2004).Fitzgerald SJ. D. Phil. Thesis. 2004. Evolution and classification of Bibionidae (Diptera: Bibionomorpha) [Google Scholar]

- Folmer et al. (1994).Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology. 1994;3:294–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadagkar & Kumar (2005).Gadagkar SR, Kumar S. Maximum likelihood outperforms maximum parsimony even when evolutionary rates are heterotachous. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2005;22:2139–2141. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagné (1989).Gagné RJ. The plant-feeding gall midges of North America. Cornell University Press; Ithaca and London: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné & Jaschhof (2014).Gagné RJ, Jaschhof M. A Catalog of the Cecidomyiidae (Diptera) of the world. 2014. Third edition. Digital version 2. http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12454900/Gagne_2014_World_Cecidomyiidae_Catalog_3rd_Edition.pdf .

- Gagné & Moser (2013).Gagné RJ, Moser JC. The North American gall midges (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) of hackberries (Cannabaceae: Celtis spp.) Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute. 2013;49:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi, Engel & Nascimbene (2002).Grimaldi DA, Engel NS, Nascimbene PC. Fossiliferous Cretaceous amber from Myanmar (Burma): its rediscovery, biotic diversity, and paleontological significance. American Museum Novitates. 2002;3361:1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert et al. (2016).Hebert PDN, Ratnasingham S, Zakharov EV, Telfer AC, Levesque-Beaudin V, Milton MA, Pedersen S, Jannetta P, DeWaard JR. Counting animal species with DNA barcodes: Canadian insects. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2016;371:20150333. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig (1954).Hennig W. Flügelgeäder und System der Dipteren unter Berücksichtigung der aus dem Mesozoikum beschriebenen Fossilien. Beiträge zur Entomologie. 1954;4:245–388. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig (1973).Hennig W. Ordnung Diptera (Zweiflügler) Handbuch der Zoologie. 1973;4(2)/1(Lfg. 20):1–227. [Google Scholar]

- Hippa, Mattsson & Vilkamaa (2005).Hippa H, Mattsson I, Vilkamaa P. New taxa of the Lygistorrhinidae (Diptera: Sciaroidea) and their implications for a phylogenetic analysis of the family. Zootaxa. 2005;960:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hippa & Ševčík (2014).Hippa H, Ševčík J. Notes on Nepaletricha (Diptera: Sciaroidea incertae sedis), with description of three new species from India and Vietnam. Acta Entomologica Musei Nationalis Pragae. 2014;54:729–739. [Google Scholar]

- Hippa & Vilkamaa (2005).Hippa H, Vilkamaa P. The genus Sciarotricha gen. n. (Sciaridae) and the phylogeny of recent and fossil Sciaroidea (Diptera) Insect Systematics, Evolution. 2005;36:121–144. doi: 10.1163/187631205788838492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hippa & Vilkamaa (2006).Hippa H, Vilkamaa P. Phylogeny of the Sciaroidea (Diptera): the implication of additional taxa and character data. Zootaxa. 2006;1132:63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffeins & Hoffeins (2014).Hoffeins C, Hoffeins HW. Diptera in Baltic amber—the most frequent order within arthropod inclusions. In: Dorchin N, Kotrba M, Mengual X, Menzel F, editors. 8th international congress of dipterology, Potsdam. 2014. p. 140 p. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck & Ronquist (2001).Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist FR. MrBayes: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Biometrics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaschhof (2001).Jaschhof M. Catotrichinae subfam. n.: a re-examination of higher classification in gall midges (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) Entomological Science. 2001;3:639–652. [Google Scholar]

- Jaschhof (2011).Jaschhof M. Phylogeny classification of the Sciaroidea (Diptera: Bibionomorpha): Where do we stand after Amorim & Rindal (2007)? BeiträGe zur Entomologie. 2011;61:455–463. [Google Scholar]

- Jaschhof & Didham (2002).Jaschhof M, Didham RK. Rangomaramidae fam. nov. from New Zealand and implications for the phylogeny of the Sciaroidea (Diptera: Bibionomorpha) Studia Dipterologica Supplement. 2002;11:1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jaschhof & Hippa (2003).Jaschhof M, Hippa H. Sciaroid but not sciarid: a review of the genus Ohakunea Tonnoir, Edwards, with the description of two new species (Insecta: Diptera: Bibionomorpha) Entomologische Abhandlungen. 2003;60:23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jaschhof & Jaschhof (2008).Jaschhof M, Jaschhof C. Catotrichinae (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) in Tasmania, with the description of Trichotoca edentula gen. et sp. n. Zootaxa. 2008;1966:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jaschhof & Jaschhof (2009).Jaschhof M, Jaschhof C. The Wood Midges (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae: Lestremiinae) of Fennoscandia and Denmark. Studia Dipterologica Supplement. 2009;18:1–333. [Google Scholar]

- Jaschhof & Jaschhof (2013).Jaschhof M, Jaschhof C. The Porricondylinae (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) of Sweden, with notes on extralimital species. Studia Dipterologica Supplement. 2013;20:1–392. [Google Scholar]

- Jaschhof et al. (2006).Jaschhof M, Jaschhof C, Viklund B, Kallweit U. On the morphology and systematic position of Sciarosoma borealis Chandler, based on new material from Fennoscandia (Diptera: Sciaroidea) Studia Dipterologica. 2006;12(2005):231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Kallweit (2014).Kallweit U. Lygistorrhina Skuse has branched from the Keroplatidae (Diptera: Sciaroidea)—a new perspective on the phylogenetic relationships in the keroplatid group of fungus gnats. In: Dorchin N, Kotrba M, Mengual X, Menzel F, editors. 8th international congress of dipterology, Potsdam. 2014. p. 156 p. [Google Scholar]

- Katana et al. (2001).Katana A, Kwiatowski J, Spalik K, Zakryś B, Szalacha E, Szymańska H. Phylogenetic position of Koliella (Chlorophyta) as inferred from nuclear and chloroplast small subunit rDNA. Journal of Phycology. 2001;37:443–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2001.037003443.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh & Standley (2013).Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambkin et al. (2013).Lambkin CL, Sinclair BJ, Pape T, Courtney GW, Skevington JH, Meier R, Yeates DK, Blagoderov V, Wiegmann BM. The phylogenetic relationships among infraorders and superfamilies of Diptera based on morphological evidence. Systematic Entomology. 2013;38:164–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2012.00652.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic & Bork (2011).Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life v2: online annotation and display of phylogenetic trees made easy. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:475–478. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matile (1990).Matile L. Recherches sur la systématique et l’évolution des Keroplatidae (Diptera, Mycetophiloidea) Mémoires du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle Paris Sér A, Zoologie. 1990;148:1–654. [Google Scholar]

- Matile (1997).Matile L. Phylogeny and evolution of the larval diet in the Sciaroidea (Diptera, Bibionomorpha) since the Mesozoic. The origin of biodiversity in insects: phylogenetic tests of evolutionary scenarios. Mémoires du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle Paris Sér A, Zoologie. 1997;173:273–303. [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen (1996).Michelsen V. Neodiptera: new insights into the adult morphology and higher level phylogeny of Diptera (Insecta) Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 1996;117:71–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1996.tb02149.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen (1999).Michelsen V. Wood gnats of the genus Sylvicola (Diptera, Anisopodidae): taxonomic status, family assignment, and review of nominal species described by J. C. Fabricius. Tijdschrift voor Entomologie. 1999;142:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Pfeiffer & Schwartz (2010).Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), 14 Nov. 2010; 2010. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Misof et al. (2014).Misof B, Liu S, Meusemann K, Peters RS, Donath A, Mayer C, Frandsen PB, Ware J, Flouri T, Beutel RG, Niehuis O, Petersen M, Izquierdo-Carrasco F, Wappler T, Rust J, Aberer AJ, Aspöck U, Aspöck H, Bartel D, Blanke A, Berger S, Böhm A, Buckley TR, Calcott B, Chen J, Friedrich F, Fukui M, Fujita M, Greve C, Grobe P, Gu S, Huang Y, Jermiin LS, Kawahara AY, Krogmann L, Kubiak M, Lanfear R, Letsch H, Li Y, Li Z, Li J, Lu H, Machida R, Mashimo Y, Kapli P, McKenna DD, Meng G, Nakagaki Y, Navarrete-Heredia JL, Ott M, Ou Y, Pass G, Podsiadlowski L, Pohl H, Von Reumont BM, Schütte K, Sekiya K, Shimizu S, Slipinski A, Stamatakis A, Song W, Su X, Szucsich NU, Tan M, Tan X, Tang M, Tang J, Timelthaler G, Tomizuka S, Trautwein M, Tong X, Uchifune T, Walzl MG, Wiegmann BM, Wilbrandt J, Wipfler B, Wong TKF, Wu Q, Wu G, Xie Y, Yang S, Yang Q, Yeates DK, Yoshizawa K, Zhang Q, Zhang R, Zhang W, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Zhou C, Zhou L, Ziesmann T, Zou S, Li Y, Xu X, Zhang Y, Yang H, Wang J, Wang J, Kjer KM, Zhou X. Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science. 2014;346:763–767. doi: 10.1126/science.1257570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulton & Wiegmann (2004).Moulton JK, Wiegmann BM. Evolution and phylogenetic utility of CAD (rudimentary) among Mesozoic-aged Eremoneuran Diptera (Insecta) Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2004;31:363–378. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylander (2004).Nylander JAA. MrModeltest v2.2 [online] 2004. Program distributed by the author, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University.

- Oosterbroek & Courtney (1995).Oosterbroek P, Courtney G. Phylogeny of the nematocerous families of Diptera (Insecta) Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 1995;115:267–311. doi: 10.1006/zjls.1995.0080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pape, Bickel & Meier (2009).Pape T, Bickel D, Meier R, editors. Diptera diversity: status, challenges and tools. Koninklijke Brill; Leiden: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Papp & Ševčík (2005).Papp L, Ševčík J. Sciarokeroplatinae, a new subfamily of Keroplatidae (Diptera) Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 2005;51:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto & Amorim (2000).Pinto LG, Amorim D. Morfologia e análise filogenética. Ribeirão Preto: Holos; 2000. Bibionidae (Diptera: Bibionomorpha) (in Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Rindal, Søli & Bachmann (2009).Rindal E, Søli GEE, Bachmann L. Molecular phylogeny of the fungus gnat family Mycetophilidae (Diptera, Mycetophiliformia) Systematic Entomology. 2009;34:524–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2009.00474.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez et al. (1990).Rodriguez F, Oliver JL, Marin A, Medina JR. The general stochastic model of nucleotide substitution. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1990;142:485–501. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5193(05)80104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roháček, Tóthová & Vaňhara (2009).Roháček J, Tóthová A, Vaňhara J. Phylogeny and affiliation of European Anthomyzidae (Diptera) based on mitochondrial 12S and 16S rRNA. Zootaxa. 2009;2054:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rohdendorf (1964).Rohdendorf BB. The historical development of two-winged insects. Trudy Paleontologiceskogo Instituta. 1964;100:1–311. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rohdendorf (1974).Rohdendorf BB. In: The historical development of Diptera [transl. from Russian] Hocking B, Oldroyd H, Ball GE, editors. University of Alberta Press; Edmonton: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Rohdendorf (1977).Rohdendorf BB. The classification and phylogeny of the Diptera. In: Scarlato OA, Gorodkov KB, editors. Systematics and evolution of the Diptera (Insecta) Zoological Institute Russian Academy of Sciences; Leningrad: 1977. (A collection of scientific works). (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ševčík et al. (2014).Ševčík J, Kaspřák D, Mantič M, Ševčíková T, Tóthová A. Molecular phylogeny of the fungus gnat family Diadocidiidae and its position within the infraorder Bibionomorpha (Diptera) Zoologica Scripta. 2014;43:370–378. doi: 10.1111/zsc.12059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ševčík, Kaspřák & Tóthová (2013).Ševčík J, Kaspřák D, Tóthová A. Molecular phylogeny of fungus gnats (Diptera: Mycetophilidae) revisited: position of Manotinae, Metanepsiini, and other enigmatic taxa as inferred from multigene analysis. Systematic Entomology. 2013;38:654–660. doi: 10.1111/syen.12023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin et al. (2013).Shin S, Jung S, Menzel F, Heller K, Lee H, Lee S. Molecular phylogeny of black fungus gnats (Diptera: Sciaroidea: Sciaridae) and the evolution of larval habitats. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2013;66:833–846. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søli (1997).Søli GEE. The adult morphology of Mycetophilidae (s.str.), with a tentative phylogeny of the family (Diptera, Sciaroidea) Entomologica Scandinavica Supplement. 1997;50:5–55. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Susko & Roger (2005).Spencer M, Susko E, Roger AJ. Likelihood, parsimony, and heterogeneous evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2005;22:1161–1164. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis (2006).Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson (1975).Thompson FC. Notes on the genus Lygistorrhina Skuse with the description of the first Nearctic species (Diptera: Mycetophiloidea) Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. 1975;77:434–445. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomikoski (1966).Tuomikoski R. Systematic position of Lygistorrhina Skuse (Diptera, Mycetophiloidea) Annales Entomologici Fennici. 1966;32:254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegmann et al. (2011).Wiegmann BM, Trautwein MD, Winkler IS, Barr NB, Kim J-W, Lambkin C, Bertone MA, Cassel BK, Bayless KM, Heimberg AM, Wheeler BM, Peterson KJ, Pape T, Sinclair BJ, Skevington JH, Blagoderov V, Caravas J, Kutty SN, Schmidt-Ott U, Kampmeier GE, Thompson FC, Grimaldi DA, Beckenbach AT, Courtney GW, Friedrich M, Meier R, Yeates DK. Episodic radiations in the fly tree of life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:5690–5695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012675108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler et al. (2015).Winkler IS, Blaschke JD, Davis DJ, Stireman JO, O’Hara JE, Cerretti P, Moulton JK. Explosive radiation or uninformative genes? Origin and early diversification of tachinid flies (Diptera: Tachinidae) Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2015;88:38–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood & Borkent (1989).Wood DM, Borkent A. Phylogeny and Classification of the Nematocera. In: McAlpine JF, Peterson BV, Shewell GE, Teskey HJ, Vockeroth JR, Wood DM, editors. Manual of Nearctic Diptera. Vol. 3. Monograph No. 27. Research Branch, Agriculture Canada; Ottawa: 1989. pp. 1333–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Xia & Xie (2001).Xia X, Xie Z. DAMBE: software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Journal of Heredity. 2001;92:371–373. doi: 10.1093/jhered/92.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitzev (1983).Zaitzev A. Anatomia pischevaritelnogo trakta lichinok nizshich micetofiloidnych dvukrylych (Diptera, Mycetophiloidea) v sviazi s ich troficheskoi specializaciei. [Anatomy of the digestive system of the larvae of lower mycetophiloid flies (Diptera, Mycetophiloidea) in connection with their trophic specialisation.] Biologicheskie Nauki. 1983;4:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitzev (1984).Zaitzev A. Osnovnye etapy specializacii rotovych aparatov lichinok micetofiloidnych dvukrylych (Diptera, Mycetophiloidea). [Main steps in specialisation of larval mouthparts of mycetophiloid flies (Diptera, Mycetophiloidea).] Biologicheskie Nauki. 1984;10:38–46. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Support numbers refer to posterior probability over 0.95/ bootstrap value over 50/ jackknife value over 50. The branches marked as “//” have been shortened to its half to fit them into the graphic.

Support numbers refer to bootstrap value over 50. The branches marked as “//” have been shortened to its half to fit them into the graphic.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Kaspřák, David (2016): Bibionomorpha alignments. Figshare: