Abstract

Background

The benefit of maintenance therapy has been confirmed in patients with non-progressing non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after first-line therapy by many trials and meta-analyses. However, since few head-to-head trials between different regimens have been reported, clinicians still have little guidance on how to select the most efficacious single-agent regimen. Hence, we present a network meta-analysis to assess the comparative treatment efficacy of several single-agent maintenance therapy regimens for stage III/IV NSCLC.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search of public databases and conference proceedings was performed. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) meeting the eligible criteria were integrated into a Bayesian network meta-analysis. The primary outcome was overall survival (OS) and the secondary outcome was progression free survival (PFS).

Results

A total of 26 trials covering 7,839 patients were identified, of which 24 trials were included in the OS analysis, while 23 trials were included in the PFS analysis. Switch-racotumomab-alum vaccine and switch-pemetrexed were identified as the most efficacious regimens based on OS (HR, 0.64; 95% CrI, 0.45–0.92) and PFS (HR, 0.54; 95% CrI, 0.26–1.04) separately. According to the rank order based on OS, switch-racotumomab-alum vaccine had the highest probability as the most effective regimen (52%), while switch-pemetrexed ranked first (34%) based on PFS.

Conclusions

Several single-agent maintenance therapy regimens can prolong OS and PFS for stage III/IV NSCLC. Switch-racotumomab-alum vaccine maintenance therapy may be the most optimal regimen, but should be confirmed by additional evidence.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer, Maintenance therapy, Bayesian network meta-analysis

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors and the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. It is estimated that about 224,390 new cases of lung and bronchus cancer will be diagnosed and 158,080 deaths will occur in 2016 in the United States alone (Siegel, Miller & Jemal, 2016). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of all lung cancer cases (Cufer, Ovcaricek & O’Brien, 2013).

For early stage NSCLC, radical surgery or radiotherapy may result in relatively better prognosis. Unfortunately, most patients (accounting for >70%) have advanced disease at diagnosis, thus are not amenable to curative treatment and are candidates for systemic therapy only, with a dismal 5-year survival rate of <5% (Rossi et al., 2014; Tan et al., 2015). The past decade has seen the evolution of individualized systemic treatment for advanced NSCLC. The development of the anti-cancer agents, especially the blossom of molecular targeted anti-tumor agents, has prolonged progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of some selected patients with specific and sensitive gene mutations (Cufer, Ovcaricek & O’Brien, 2013). Nonetheless, as these mutations only occur in a small percentage of patients, 4–6 cycles of platinum-based double-agent chemotherapy is still the gold-standard regimen recommended by guidelines for most patients with non-resectable, locally-advanced, or metastatic NSCLC (Azzoli et al., 2011; Besse et al., 2014; Ettinger et al., 2015). Additionally, prolonged platinum-based doublet therapies show increased toxicity and no meaningful improvement in OS (Lima et al., 2009). In the past, patients who successfully responded to front-line therapy had to wait for disease progression before receiving second-line or other treatment, and unfortunately, nearly half of them could not proceed with second-line therapy, mostly due to their declining performance status (PS) (Berge & Doebele, 2013). In recent years, more attention has been focused on maintenance therapy, which refers to the extension of one or more agents to non-progressing patients after first-line induction chemotherapy (Owonikoko, Ramalingam & Belani, 2010).

Although relatively new for NSCLC, maintenance therapy has been used in the treatment of hematologic malignancies for years (Childhood ALL Collaborative Group, 1996; Salles et al., 2011). Continued use of at least one of the drugs given in induction therapy is defined as continuation maintenance, whereas switch maintenance refers to administration of a totally different agent from first-line chemotherapy (Ettinger et al., 2015). Switch-pemetrexed therapy has shown improvement of both OS and PFS compared to placebo as single-agent maintenance in Ciuleanu’s trial (Ciuleanu et al., 2009), as well as switch-erlotinib in Cappuzzo’s trial (Cappuzzo et al., 2010); and both have been approved by Food and Drug Administration for maintenance therapy of advanced NSCLC patients non-progressing after 4 cycles of platinum-based first-line chemotherapy in the United States (Cohen et al., 2010a; Cohen et al., 2010b). Former meta-analyses studies have confirmed that single-agent maintenance therapy can prolong OS and PFS in contrast to non-maintenance regimens (Behera et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015). Factors that may predict beneficial effects from maintenance therapy include tumor histology, PS, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation status (Zhou et al., 2015).

The recent inclusion of various agents such as sunitinib, pazopanib, and some vaccines in anti-tumor therapy, has propelled research into their use as maintenance therapy options for NSCLC (Ahn et al., 2013; Alfonso et al., 2014; Butts et al., 2005; Giaccone et al., 2015; O’Brien et al., 2015; Socinski et al., 2014). Some classic randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of maintenance therapy, such as the INFORM study (Zhao et al., 2015), have updated their final survival statistics as well. Nevertheless, the relative effects of any of these maintenance regimens compared with other regimens remain unclear due to lack of evidence from head-to-head RCTs. Network meta-analysis (NMA) can simultaneously synthesize evidence from both direct and indirect comparisons of diverse regimens into a single network, which enables us to estimate the relative efficacy of several agents when head-to-head RCTs are not available (Salanti et al., 2008). By adopting Bayesian approach in the analysis, we can rank the relative efficacy of these regimens by calculating the corresponding probability of OS (Ades et al., 2006). Hence, herein, we present a NMA to assess the efficacy of various single-agent maintenance therapy strategies for stage III/IV NSCLC. It is our belief that this analysis will provide some clinical evidence for clinicians to make decisions on maintenance therapy for NSCLC.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive literature search of PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) from inception to November 09, 2015. We administered a high sensitivity searched strategy with keywords set around “non-small cell lung cancer,” “maintenance therapy,” and “RCT.” No language restriction was administered. Details of the search strategy are presented in Supplemental Information 1. We also manually searched proceedings of the annual American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meetings and European Society of Medical Oncology (ESCO) congresses from 2000 to 2015 as a supplement. Citations of relevant reviews and trials were also screened. All results were input into Endnote X7 reference software (Thomson Reuters, Stamford, CT, US) for duplication exclusion and further reference management.

Selection of trials

Studies meeting the following inclusion criteria were eligible: (i) RCTs, (ii) patients were pathologically or cytologically-diagnosed with non-resectable stage III or IV NSCLC, (iii) comparisons had to be between single-agent maintenance therapy and placebo, observation, or another single-agent maintenance regimen, and (iv) sufficient data on OS or/and PFS. Trials with randomization conducted before induction therapy and trials of complementary medicine were excluded. When multiple publications reported on one trial, we selected the most recent report for data extraction.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Data was independently extracted by two reviewers (Q Wang and H Huang) using standardized data compilation forms. Name of the first author, publication year, number of patients and population characteristics, induction and maintenance therapy regimens, survival statistics, adverse effects (AEs) were major aspects included. The hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were either obtained from the original articles or estimated from Kaplan–Meier curves using Tierney’s spreadsheet (Tierney et al., 2007). For each included trial, the following domains of bias were judged and ranked into “low risk,” “high risk,” or “unclear risk”: generation of random sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting of outcome, and other biases. Two investigators (Q Wang and H Huang) independently performed the assessment. All divergences during data extraction and assessment of risk of bias were solved by discussion with a third investigator (M Huang).

Statistical analysis

The NMA combined evidence from head-to-head comparisons into a network to obtain estimates of the relative efficacy of each treatment. Analyses were conducted using R 3.0.1 (R Development Core Team, 2013) with an interface to WinBUGS 1.4.3 (Medical Research Council Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK). We built a network within the Bayesian framework and the posterior distribution of the treatment effect was estimated using Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods.

For the three-arm trial Perol 2012, log HRs (contrast statistics) were converted to log HRs (arm-specific statistics) according to the method introduced by Woods, Hawkins & Scott (2010).

All analyses were performed with 2 chains, and each had a sample of 200,000 simulations after discarding the results of a burn-in period of 40,000 simulations. We estimated the relative treatment effects based on the posterior distributions and ranked the probability for each treatment in descending order as the most efficacious regimen, the second, the third, and so on, according to OS and PFS separately. Since OS is the most concerned outcome in clinical trials of antitumor therapy, we set OS as the primary outcome in our analysis and draw conclusions based on OS mainly. The deviance information criterion (DIC) provided a measure of model fit that a lower value suggested a simpler model. Convergence of the model was assessed with the Brooks–Gelman–Rubin diagnostic methods in WinBUGS.

Both fixed and random effects models were administered in the primary analysis; posterior mean of the residual deviance (resdev), effective number of parameters (pD), and DIC results of the two models were compared in sensitivity analysis. We assessed the inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence using the method suggested by Veroniki et al. (2013). We also assessed the probability of publication bias with contour-enhanced funnel plots (Peters et al., 2008).

Quality assessment of evidence

We assessed the quality of evidence in two steps. First, we used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system to assess quality of direct evidence (Guyatt et al., 2011). GRADE focuses on a body of evidence rather than individual studies. RCTs were initially identified as high quality of evidence and identification of problems on limitations in trial design, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias decreased the evidence quality rating. Quality of evidence was rated as high, moderate, low or very low. Then, we used the iGRADE approach, which is a modification of the GRADE approach for mixed treatment comparisons proposed by Dumville et al. (2012), to evaluate the quality of NMA evidence.

Results

Characteristics of eligible studies

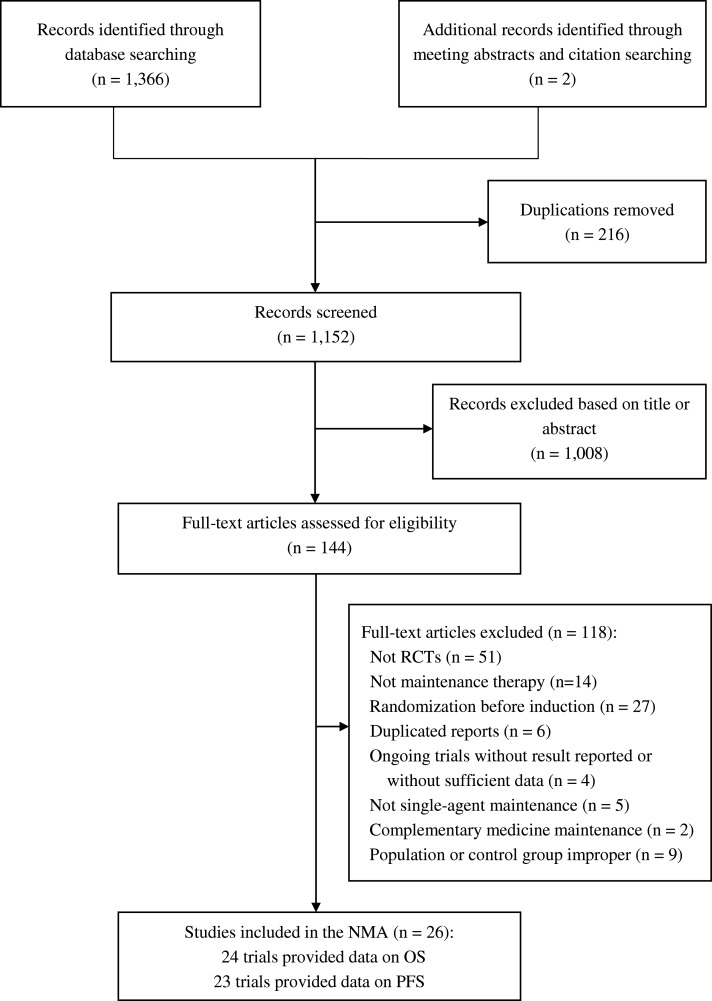

Through online databases and meeting abstracts searches, a total of 1,368 records were identified. After rounds of assessment, 26 trials covering 7,839 patients met all the inclusion criteria, and comprised of 24 complete manuscripts (Ahn et al., 2013; Alfonso et al., 2014; Belani et al., 2003; Brodowicz et al., 2006; Butts et al., 2005; Butts et al., 2014; Cai et al., 2015; Cappuzzo et al., 2010; Carter et al., 2012; Ciuleanu et al., 2009; Fidias et al., 2009; Gaafar et al., 2011; Giaccone et al., 2015; Hanna et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2008; Karayama et al., 2013; Kelly et al., 2008; Mubarak et al., 2012; O’Brien et al., 2015; Pérol et al., 2012; Paz-Ares et al., 2013; Westeel et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2012) and 2 meeting abstracts (Belani et al., 2010; Socinski et al., 2014). Selection procedure is summarized in Fig. 1. Summary of characteristics of the 26 eligible studies and HR data of each individual study is shown in Table 1. With the exception of Perol 2012 which was a three-arm trial (continue-gemcitabine or switch-erlotinib vs. observation) and Karayama 2013 which compared two maintenance regimens directly (continue-pemetrexed vs. switch-docetaxel); the remaining 24 trials all compared single-agent maintenance therapy vs. no-maintenance control. The network of evidence constructed by the included RCTs is shown in Fig. 2. Risks of bias of the enrolled studies are depicted in Table S1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of trial selection.

RCT, randomized controlled trial; NMA, network meta-analysis; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival.

Table 1. General characteristics of the eligible RCTs.

| Name/year (study name) | Number of maintenance | Population | Induction therapy | Maintenance therapy | Median age (years) | Males (%) | Squamous cell carcinoma (%) | HR (95% CrI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | C | OS | PFS | |||||||

| Belani 2003 | 65 | 65 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-2 | Paclitaxel + carboplatin | Con-pac 70 mg/m2 weekly for 3 of 4 weeks; Observation | 65.5 | 81.3 | NR | 1.21a (0.72–2.03) | / |

| Butts 2005 | 88 | 83 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-2 | Platinum-based CT alone or CT + radiotherapy | Swi-BLP 1,000 µg weekly for 8 weeks + BSC; BSC | 59 | 55.6 | NR | 0.75b (0.53–1.04) | / |

| Westeel 2005 | 91 | 90 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/ IV NSCLC, WHO PS 0-2 | MIC + cisplatin (+ radiotherapy for IIIB) | Swi-vin 25 mg/m2 weekly for 6 months; Observation | 62.5 | 92.8 | 59.7 | 1.08b (0.79–1.47) | 0.77b (0.56–1.07) |

| Brodowicz 2006 | 138 | 68 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/ IV NSCLC, KPS ≥ 70 | Gemcitabine + cisplatin | Con-gem 1,250 mg/m2 on days 1 & 8 of a 21-day cycle until PD or unacceptable toxicity; BSC | 57.3 | 73.3 | 40.8 | 0.84a (0.52–1.37) | 0.69a (0.56–0.86) |

| Hanna 2008 | 73 | 74 | CT-naïve, unresectable stage IIIA/IIIB NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Etoposide + cisplatin | Swi-doc 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for 3 cycles; Observation | 62 | 70.1 | NR | 1.06a (0.75–1.50) | 1.01a (0.77–1.33) |

| Johnson 2008 | 94 | 92 | CT-naïve, stage III/IV NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-2 | Platinum-based CT | Swi-CAI 250 mg/d until PD or unacceptable toxicity; Placebo | 65.8 | 57.5 | 18.3 | 1.03a (0.77–1.37) | 1.02a (0.82–1.27) |

| Kelly 2008 (SWOG S0023) | 118 | 125 | CT-naïve, unresectable stage IIIA/IIIB NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Etoposide + cisplatin + radiotherapy | Swi-gef 500 mg/d for 5 years or until PD or unacceptable toxicity; Placebo | 61.5 | 63.0 | 24.7 | 0.63c (0.44–0.91) | 0.80c (0.58–1.10) |

| Ciuleanu 2009 (JMEN) | 441 | 222 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Platinum-based CT (not include pemetrexed) | Swi-pem 500 mg/m2 on day 1 of a 21-day cycle; Placebo | 60.5 | 72.9 | 27.5 | 0.79c (0.65–0.95) | 0.50c (0.42–0.61) |

| Fidias 2009 | 153 | 156 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-2 | Gemcitabine + carboplatin | Swi-doc 75 mg/m2 on day 1 of a 21-day cycle until PD (maximum of 6 cycles); BSC + delayed docetaxel 75 mg/m2 on day 1 of a 21-day cycle (maximum of 6 cycles) once PD; | 65.5 | 62.1 | 17.5 | / | 0.71c (0.55–0.92) |

| Belani 2010 | 128 | 127 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Gemcitabine + carboplatin | Con-gem 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 & 8 of a 21-day cycle until PD + BSC; BSC | 67.0 | NR | NR | 0.97c (0.72–1.30) | 0.97c (0.92–1.04) |

| Cappuzzo 2010 (SATURN; BO18192) | 438 | 451 | CT-naïve recurrent or stage IIIB/IV NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Platinum-based CT | Swi-erl 150 mg/d until PD or unacceptable toxicity; Placebo | 60 | 74.1 | 40.6 | 0.81c (0.70–0.95) | 0.71c (0.62–0.82) |

| Hu 2010 | 33 | 30 | CT-naïve, unresectable stage IIIA/IIIB NSCLC, PS 0-1 | Platinum-based CT + radiotherapy | Swi-vin 21 mg/m2 on days 1 & 8 of a 28-day cycle for 6 cycles; Observation | 56.7 | 58.7 | 46.0 | 0.89a (0.55–1.43) | / |

| Gaafar 2011 (EORTC 08021/ILCP 01/03) | 87 | 86 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV NSCLC, WHO PS 0-2 | Platinum-based CT | Swi-gef 250 mg/d; Placebo | 61.0 | 77.0 | 20.0 | 0.83c (0.60–1.15) | 0.61c (0.45–0.83) |

| Carter 2012 | 61 | 58 | CT-naïve, unresectable stage IIIA/IIIB NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Paclitaxel + carboplatin + radiotherapy | Con-pac 70 mg/m2 weekly for 3 of 4 weeks for 6 months; Observation | 63.5 | 33.6 | 23.5 | 1.22a (0.75–1.99) | 1.51a (1.04–2.19) |

| Mubarak 2012 | 61 | 59 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV non-squamous NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Pemetrexed + cisplatin | Con-pem 500 mg/m2 of a 21-day cycle until PD or unacceptable toxicity+ BSC; BSC | 60.0 | 67.3 | 0 | 0.95c (0.46–1.97) | 0.65c (0.35–1.20) |

| Perol 2012 (IFCT-GFPC 0502) | 154 | 155 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Gemcitabine + cisplatin | Con-gem 1,250 mg/m2 on days 1 & 8 of a 21-day cycle; Swi-erl 150 mg/d; Observation | 58.3 | 73.0 | 19.6 | 0.89c (0.62–1.28) | 0.56c (0.44–0.72) |

| 155 | 0.87c (0.68–1.13) | 0.69c (0.54–0.88) | ||||||||

| Zhang 2012 (INFORM; C-TONG 0804) | 148 | 148 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV NSCLC, WHO PS 0-2 | Platinum-based CT | Swi-gef 250 mg/d; Placebo | 55.0 | 40.9 | 19.3 | 0.88b (0.68–1.14) | 0.42b (0.33–0.55) |

| Ahn 2013 (NCT00777179) | 75 | 42 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB or IV NSCLC, WHO PS 0-1 | Gemcitabine + cisplatin | Swi-van 300 mg/d + BSC; Placebo + BSC | 61.0 | 64.1 | 17.1 | 1.43a (0.77–2.65) | 0.75a (0.53–1.05) |

| Karayama 2013 | 26 | / | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV non-squamous NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Pemetrexed + carboplatin | Con-pem 500 mg/m2 on day 1 of a 21-day cycle; Swi-doc 60 mg/m2 on day 1 of a 21-day cycle | 65.0 | 74.1 | 0 | 1.27c (0.50–3.33) | 1.79c (0.93–3.57) |

| 25 | ||||||||||

| Paz-Ares 2013 (PARAMOUNT) | 359 | 180 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV non-squamous NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Pemetrexed + cisplatin | Con-pem 500 mg/m2on day 1 of a 21-day cycle + BSC; Placebo + BSC | 61.0 | 58.1 | 0 | 0.78c (0.64–0.96) | 0.62c (0.49–0.79) |

| Alfonso 2014 | 87 | 89 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV non-squamous NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-2 | Platinum-based CT (+ radiotherapy) | Swi-rac 1 mg, 5 immunizations every 2 weeks and reimmunizations every 4 weeks for 1 year; Placebo | NR | 67.0 | 37.5 | 0.63c (0.46–0.87) | 0.73c (0.53–0.99) |

| Butts 2014 (START) | 829 | 410 | CT-naïve, unresectable stage IIIA/IIIB NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Platinum-based CT + radiotherapy | Swi-BLP weekly for 8 weeks and then every 6 weeks until PD; Placebo | 61.2 | 68.3 | 46.2 | 0.88b (0.75–1.03) | 0.87b (0.75–1.00) |

| Socinski 2014 (CALGB 30607) | 106 | 104 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV non-squamous NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-1 | Platinum-based CT | Swi-sun 37.5 mg/d; Placebo | 66.0 | 55.7 | 33.2 | 1.08a (0.78–1.52) | 0.59a (0.32–1.21) |

| Cai 2015 | 7 | 7 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV EGFR gene-mutated NSCLC, PS 0-2 | Paclitaxel + cisplatin | Swi-gef 250 mg/d; Observation | 61.0 | 53.3 | 0 | / | 0.60a (0.03–11.33) |

| Giaccone 2015 | 270 | 262 | CT-naïve, unresectable stage IIIA/IIIB/IV NSCLC, ECOG PS 0-2 | Platinum-based CT (+ radiotherapy) | Swi-bel monthly for 18 cycles followed by 2 quarterly cycles; Placebo | 61.0 | 57.7 | 27.4 | 0.94c (0.73–1.20) | 0.99c (0.82–1.20) |

| O’Brien 2015 (EORTC 08092) | 50 | 52 | CT-naïve, stage IIIB/IV NSCLC, WHO PS 0-2 | Platinum-based CT | Swi-paz 800 mg/d; Placeb | 64.4 | 45.1 | 19.6 | 0.72c (0.40–1.28) | 0.67c (0.43–1.03) |

Notes.

Unadjusted HRs estimated from Kaplan–Meier curves using Tierney’s spreadsheet.

Adjusted HRs obtained from the original articles.

Unadjusted HRs obtained from the original articles.

Abbreviations

- BSC

- best support care

- NR

- not reported

- ECOG

- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- CT

- chemotherapy

- L-BLP25

- tecemotide

- MIC

- mitomycin C

- KPS

- Karnofsky performance status

- PD

- progressive disease

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor receptor

- OS

- overallsurvival

- PFS

- progression free survival

- HR

- hazard ratio

- CrI

- credible interval

- swi-pem

- switch-pemetrexed

- con-pem

- continue-pemetrexed

- swi-gef

- switch-gefitinib

- con-gem

- continue-gemcitabine

- swi-erl

- switch-erlotinib

- swi-doc

- switch-docetaxel

- con-pac

- continue-paclitaxel

- swi-BLP

- switch-L-BLP25

- swi-bel

- switch-belagenpumatucel-L

- swi-paz

- switch-pazopanib

- swi-sun

- switch-sunitinib

- swi-van

- switch-vandetanib

- swi-CAI

- switch-carboxyaminoimidazole

- swi-vin

- switch-vinorelbine

- swi-rac

- switch-racotumomab-alum

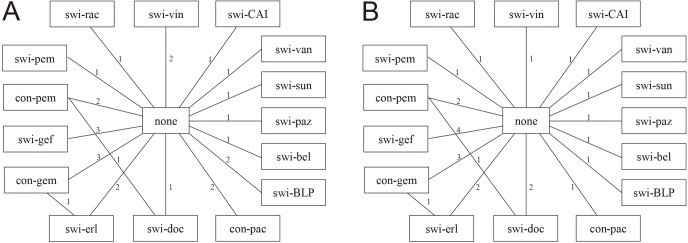

Figure 2. Network of evidence.

(A) and (B) present network diagrams for OS and PFS separately. Numbers above the lines represent the amount of studies. Swi-pem, switch-pemetrexed; con-pem, continue-pemetrexed; swi-gef, switch-gefitinib; con-gem, continue-gemcitabine; swi-erl, switch-erlotinib; swi-doc, switch-docetaxel; con-pac, continue-paclitaxel; swi-BLP, switch-L-BLP25; swi-bel, switch-belagenpumatucel-L ; swi-paz, switch-pazopanib; swi-sun, switch-sunitinib; swi-van, switch-vandetanib; swi-CAI, switch-carboxyaminoimidazole; swi-vin, switch-vinorelbine; swi-rac, switch-racotumomab-alum.

OS and PFS analyses

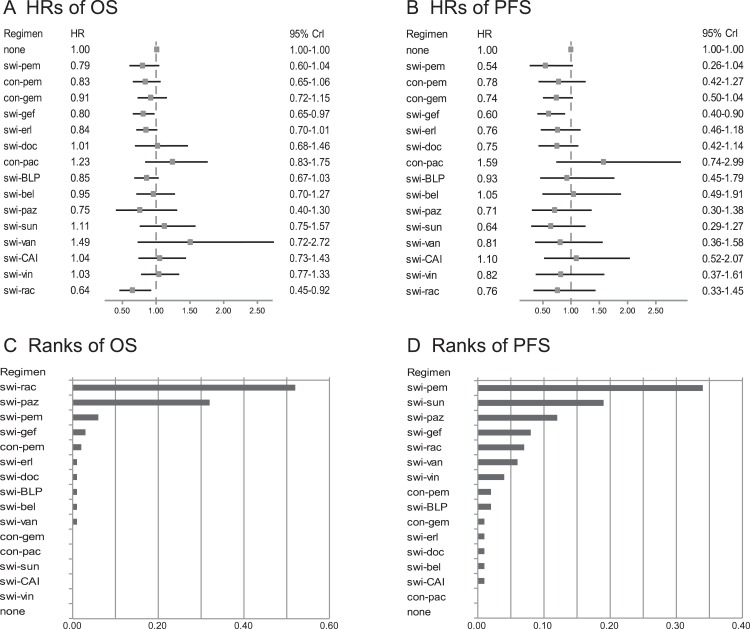

In total, 24 trials were included in the OS analysis (Ahn et al., 2013; Alfonso et al., 2014; Belani et al., 2003; Belani et al., 2010; Brodowicz et al., 2006; Butts et al., 2005; Butts et al., 2014; Cappuzzo et al., 2010; Carter et al., 2012; Ciuleanu et al., 2009; Fidias et al., 2009; Gaafar et al., 2011; Giaccone et al., 2015; Hanna et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2008; Karayama et al., 2013; Kelly et al., 2008; Mubarak et al., 2012; O’Brien et al., 2015; Pérol et al., 2012; Paz-Ares et al., 2013; Westeel et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2012). No-maintenance control was set as the reference in all analyses. Based on assessment of model fit, results calculated by random effects models are presented in this section. The HRs for different maintenance regimens compared to no-maintenance are shown in Fig. 3A. Several maintenance therapy regimens yielded longer OS than no-maintenance, although differences were not statistically significant in some regimens. Switch-docetaxel, continue-paclitaxel, switch-sunitinib, switch-vandetanib, switch-carboxyaminoimidazole (CAI), and switch-vinorelbine did not improve OS. Switch-maintenance therapy with racotumomab-alum vaccine showed excellent efficacy compared to no-maintenance with a HR = 0.64 [95% credible intervals (CrI), 0.45–0.92] Pooled relative treatment effect estimates of all comparisons are presented in Table S2.

Figure 3. OS and PFS analyses in total population.

(A) and (B) show comparisons of HRs based on OS and PFS respectively in an unselected population. Switch-racotumomab-alum vaccine showed most excellent efficacy compared to no-maintenance with a HR = 0.64 (95% CI [0.45–0.92]) in OS analysis, as well as switch-pemetrexed (HR, 0.54; 95% CI [0.26–1.04]) in PFS analysis. (C) and (D) show the probability of every regimen to be the best one based on OS and PFS respectively in an unselected population. According to the rank order based on OS, switch-racotumomab-alum vaccine came first (52%). Based on PFS, switch-pemetrexed ranked first (34%). Swi-pem, switch-pemetrexed; con-pem, continue-pemetrexed; swi-gef, switch-gefitinib; con-gem, continue-gemcitabine; swi-erl, switch-erlotinib; swi-doc, switch-docetaxel; con-pac, continue-paclitaxel; swi-BLP, switch-L-BLP25; swi-bel, switch-belagenpumatucel-L; swi-paz, switch-pazopanib; swi-sun, switch-sunitinib; swi-van, switch-vandetanib; swi-CAI, switch-carboxyaminoimidazole; swi-vin, switch-vinorelbine; swi-rac, switch-racotumomab-alum; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CrI, credible interval.

In PFS analysis, we included 23 trials (Ahn et al., 2013; Alfonso et al., 2014; Belani et al., 2010; Brodowicz et al., 2006; Butts et al., 2014; Cai et al., 2015; Cappuzzo et al., 2010; Carter et al., 2012; Ciuleanu et al., 2009; Fidias et al., 2009; Gaafar et al., 2011; Giaccone et al., 2015; Hanna et al., 2008; Johnson et al., 2008; Karayama et al., 2013; Kelly et al., 2008; Mubarak et al., 2012; O’Brien et al., 2015; Pérol et al., 2012; Paz-Ares et al., 2013; Socinski et al., 2014; Westeel et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2012). The HRs for different maintenance regimens compared to no-maintenance regimens are shown in Fig. 3B. Continue-paclitaxel, switch-belagenpumatucel-L, or switch-CAI did not yield longer PFS than no-maintenance. Switch-pemetrexed and switch-gefitinib showed excellent efficacy compared to no-maintenance with HRs = 0.54 (95% CI [0.26–1.04]) and 0.60 (95% CI [0.40–0.90]). Pooled relative treatment effect estimates of all comparisons are presented in Table S2.

Ranking which indicated the probability of the best regimen in descending order, among all treatments is shown in Figs. 3C, 3D and Table 2. According to the rank order based on OS, switch-racotumomab-alum vaccine had the greatest probability as the best regimen (52%), with switch-pazopanib ranked second (32%), and switch-pemetrexed ranked third (6%). Based on PFS, switch-pemetrexed ranked first (34%), followed by switch-sunitinib (19%), with switch-pazopanib ranked third (12%).

Table 2. Rank orders.

| Regimen | R 1 | R 2 | R 3 | R 4 | R 5 | R 6 | R 7 | R 8 | R 9 | R 10 | R 11 | R 12 | R 13 | R 14 | R 15 | R 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | ||||||||||||||||

| none | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| swi-pem | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| con-pem | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| con-gem | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| swi-gef | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| swi-erl | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| swi-doc | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| con-pac | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.21 |

| swi-BLP | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| swi-bel | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| swi-paz | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| swi-sun | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.08 |

| swi-van | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.57 |

| swi-CAI | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| swi-vin | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| swi-rac | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PFS | ||||||||||||||||

| none | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| swi-pem | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| con-pem | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| con-gem | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| swi-gef | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| swi-erl | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| swi-doc | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| con-pac | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.61 |

| swi-BLP | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| swi-bel | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.11 |

| swi-paz | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| swi-sun | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| swi-van | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| swi-CAI | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.13 |

| swi-vin | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| swi-rac | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

Notes.

Abbreviations

- R

- rank

- OS

- overallsurvival

- PFS

- progression free survival

- HR

- hazard ratio

- CrI

- credible interval

- swi-pem

- switch-pemetrexed

- con-pem

- continue-pemetrexed

- swi-gef

- switch-gefitinib

- con-gem

- continue-gemcitabine

- swi-erl

- switch-erlotinib

- swi-doc

- switch-docetaxel

- con-pac

- continue-paclitaxel

- swi-BLP

- switch-L-BLP25

- swi-bel

- switch-belagenpumatucel-L

- swi-paz

- switch-pazopanib

- swi-sun

- switch-sunitinib

- swi-van

- switch-vandetanib

- swi-CAI

- switch-carboxyaminoimidazole

- swi-vin

- switch-vinorelbine

- swi-rac

- switch-racotumomab-alum

Adverse events (AEs)

Maintenance chemotherapy (including pemetrexed, gemcitabine, docetaxel, paclitaxel, and vinorelbine) was commonly associated with hematologic events such as neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia. Maintenance tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) (including EGFR-TKI and other TKIs) commonly caused more skin and gastrointestinal AEs, such as rash, nausea, and vomiting. Maintenance vaccine (including belagenpumatucel-L, racotumomab-alum, and L-BLP25) was commonly associated with injection site reaction and flu-like symptoms. The main AE of CAI was nausea.

Sensitivity analysis

The primary outcome OS was calculated using both fixed and random effects models. Resdev, pD and DIC were very similar for both models (−23.37, 15.8 and −7.5 in fixed effects model; −23.33, 17.3 and −6.0 in random effects model), which indicated the robustness of results.

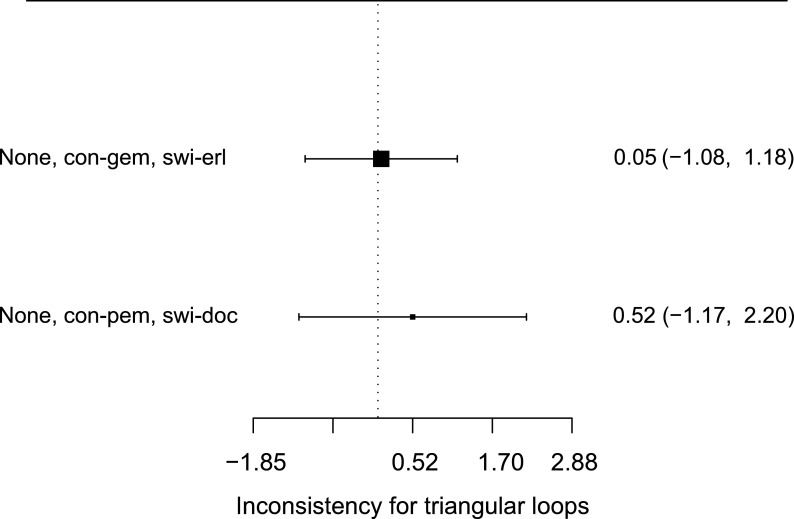

Inconsistencies

The data did not suggest any inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence in the network (Fig. 4). In fact, direct evidence of the relative efficacy of different maintenance therapy regimens was rather few in the network. In the analysis of OS, only two closed loops were formed (none vs. continue-gemcitabine vs. switch-erlotinib; none vs. continue-pemetrexed vs. switch-docetaxel).

Figure 4. Inconsistencies evaluation (based on OS).

Only two closed loops were formed (none vs. con-gem vs. swi-erl; none vs. con-pem vs. swi-doc) in this NMA. The size of the black square represented the amount of included studies. Both loops had their credible intervals covered blank value, which meant there was no evidence of inconsistencies between direct and indirect data.

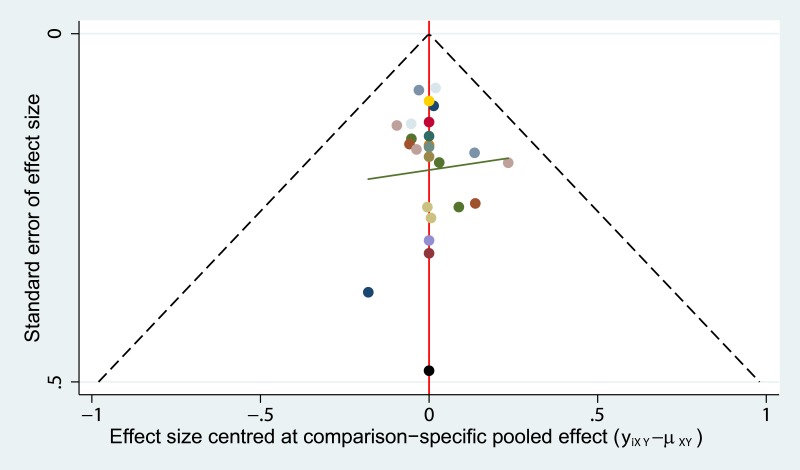

Publication bias

Symmetry of the ‘comparison-adjusted’ funnel plot suggested that efficacy of the regimens were no more exaggerated than their respective comparison-specific weighted average effect in small studies. The regimens also sorted from oldest to newest, and the resulting ‘comparison-adjusted’ funnel plot did not suggest any publication bias in the network (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Publication bias (based on OS).

The funnel plot did not suggest any publication bias in the network.

Quality assessment

GRADE and iGRADE analyses are presented in Table S3. Since direct data comparing different maintenance therapy regimens was available for only two couples of regimens, measurement of inconsistencies between direct and indirect data was limited. In general, the most common reasons for lowering the quality of evidence were limitations in trial design and imprecision in some studies. Data suggested that evidence on switch-docetaxel, continue-paclitaxel and switch-vinorelbine were rated as limited quality, while evidence on switch-pemetrexed, switch-belagenpumatucel-L and switch-racotumomab-alum was rated as higher quality.

Discussion

Although recent evidence provided by both RCTs and meta-analyses have shown that maintenance therapy might improve the outcomes of patients without progressive disease (PD) after induction treatment, there is still little guidance on the choice of the most suitable regimens for patients with different characteristics in clinical practice. This NMA study compared the survival benefits among all available single-agent maintenance regimens based on OS and PFS in unselected population with the aim of providing beneficial information for making clinical decisions for NSCLC maintenance therapy.

Comparing to chemotherapy as well as EGFR-TKIs, cancer vaccines are a relative new treatment strategy but show promise in NSCLC therapy. NeuGcGM3 gangliosides are normally expressed on the plasma membranes of mammalian cells except human cells, due to a 92-bp deletion in the human gene that encodes an enzyme which catalyzes the conversion of N-acetyl to NeuGc sialic acid (Alfonso et al., 2014). However, NeuGcGM3 gangliosides are over-expressed on several tumor cells membranes, such as melanoma, breast cancer, and NSCLC. In addition, NeuGcGM3 gangliosides also play important roles in tumor biology, including promoting tumor metastasis and reinforcing tumor immune escape. Furthermore, NSCLC patients with higher expression of NeuGc gangliosides have lower OS and PFS. All the above characteristics make NeuGc gangliosides attractive targets for tumor immunotherapy (Hernández & Vázquez, 2015). Racotumomab-alum vaccine is an anti-idiotype vaccine targeting the NeuGcGM3 tumor-associated gangliosides, which can bind and directly kill NSCLC cells expressing the antigen. According to our NMA in unselected population, switch-racotumomab-alum vaccine might be the most efficacious maintenance regimen in prolonging OS. Switch-racotumomab-alum can decrease the hazard for death to 0.64. However, since there was only one study (176 patients) on racotumomab-alum vaccine, additional RCT studies with larger patient populations are required to confirm this finding. At present, racotumomab-alum vaccine is marketed in Cuba and Peru as maintenance therapy for NSCLC patients. Meanwhile, clinical researches are underway in the United Kingdom and China.

Switch-pemetrexed and switch- pazopanib maintenance therapy also revealed favorable effect in prolonging OS. Pemetrexed has shown different effects according to pathological category of NSCLC, and is extremely efficacious for non-squamous NSCLC. In Ciuleanu’s study, switch-pemetrexed maintenance therapy decreased the HRs for OS and PFS to 0.70 (95% CI [0.56–0.88]) and 0.44 (95% CI [0.36–0.55]) in non-squamous population, which was significantly better than in the squamous population (OS HR 1.07, 95% CI [0.77–1.50]; and PFS HR 0.69, 0.49–0.98) (Ciuleanu et al., 2009). Therefore, switch-pemetrexed may be an efficacious regimen for non-squamous NSCLC. However, these two maintenance regimens have each been investigated in single eligible studies, therefore additional studies are required to confirm these observations.

Our NMA still has several limitations. Firstly, some regimens had few trials eligible for analysis, thus their small sample sizes may influence the reliability of outcomes. Secondly, since different agents and regimens have their particular target population, treating all unselected NSCLC patients as a whole may lead to the underestimation of some efficacious regimens. Thirdly, single bevacizumab maintenance therapy as a potential effective regimen has been investigated in AVAPERL (Barlesi et al., 2011) and ATLAS (Johnson et al., 2013) trials. However, since both of those two studies did not incorporate no-maintenance therapy as control, we could not integrate them into the network, thus the efficacy of bevacizumab maintenance was not compared to the other regimens.

Survival outcomes of patients receiving maintenance therapy are influenced by post-study therapy. However, most of the included studies did not provide detailed information about the effect of post-study therapy on survival. Some studies have reported that though maintenance therapy could improve PFS, there were no significant differences in OS (Ahn et al., 2013; Pérol et al., 2012). We supposed the nonconformity between PFS and OS results may partly be due to the choice of different post-study therapy. Thus, in our NMA, we also set PFS as an outcome to analysis. Future studies could choose maintenance regimen with PFS benefit continued with different post-maintenance therapies to determine which combination has the best OS outcome. Apart from efficacy and safety, the quality of life of patients and the cost-effectiveness of maintenance therapy should be taken into consideration when choosing maintenance therapy. Future studies should incorporate all these aspects in their study design and analysis.

In conclusion, our NMA demonstrates that several single-agent maintenance therapy regimens may prolong OS and PFS for stage III/IV NSCLC. Racotumomab-alum vaccine has shown potential survival benefit in unselected NSCLC population but should be confirmed with additional clinical evidence.

Supplemental Information

Acknowledgments

We thank LetPub (http://www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a grant from the Jiangsu Province Special Program of Medical Science (BL2012012). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xin Zhao, Email: xinzhao1104@126.com.

Mao Huang, Email: huangmao6114@126.com.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Qinxue Wang and Haobin Huang conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Xiaoning Zeng performed the experiments, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Yuan Ma performed the experiments, wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Xin Zhao and Mao Huang conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data has been supplied as a Supplementary File.

References

- Ades et al. (2006).Ades AE, Sculpher M, Sutton A, Abrams K, Cooper N, Welton N, Lu G. Bayesian methods for evidence synthesis in cost-effectiveness analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:1–19. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200624010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn et al. (2013).Ahn JS, Lee KH, Sun JM, Park K, Kang ES, Cho EK, Lee DH, Kim SW, Lee GW, Kang JH, Lee JS, Lee JW, Ahn MJ. A randomized, phase II study of vandetanib maintenance for advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer following first-line platinum-doublet chemotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2013;82:455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso et al. (2014).Alfonso S, Valdes-Zayas A, Santiesteban ER, Flores YI, Areces F, Hernandez M, Viada CE, Mendoza IC, Guerra PP, Garcia E, Ortiz RA, De la Torre AV, Cepeda M, Perez K, Chong E, Hernandez AM, Toledo D, Gonzalez Z, Mazorra Z, Crombet T, Perez R, Vazquez AM, Macias AE. A randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical trial of racotumomab-alum vaccine as switch maintenance therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clinical Cancer Research. 2014;20:3660–3671. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzoli et al. (2011).Azzoli CG, Temin S, Aliff T, Baker Jr S, Brahmer J, Johnson DH, Laskin JL, Masters G, Milton D, Nordquist L, Pao W, Pfister DG, Piantadosi S, Schiller JH, Smith R, Smith TJ, Strawn JR, Trent D, Giaccone G, American Society of Clinical Oncology 2011 Focused update of 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update on chemotherapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:3825–3831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlesi et al. (2011).Barlesi F, de Castro J, Dvornichenko V, Kim JH, Pazzola A, Rittmeyer A, Vikström A, Mitchell L, Wong EK, Gorbunova V. AVAPERL (MO22089): final efficacy outcomes for patients (pts) with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (nsNSCLC) randomised to continuation maintenance (mtc) with bevacizumab (bev) or bev + pemetrexed (pem) after first-line (1L) bev-cisplatin (cis)-pem treatment (Tx) . AbstractEuropean Journal of Cancer. 2011;47(Suppl. 2):16. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)70133-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behera et al. (2012).Behera M, Owonikoko TK, Chen Z, Kono SA, Khuri FR, Belani CP, Ramalingam SS. Single agent maintenance therapy for advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2012;77:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belani et al. (2003).Belani CP, Barstis J, Perry MC, La Rocca RV, Nattam SR, Rinaldi D, Clark R, Mills GM. Multicenter, randomized trial for stage IIIB or IVnon-small-cell lung cancer using weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by maintenance weekly paclitaxel or observation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:2933–2939. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belani et al. (2010).Belani CP, Waterhouse DM, Ghazal H, Ramalingam SS, Bordoni R, Greenberg R, Levine RM, Waples JM, Jiang Y, Reznikoff G. Phase III study of maintenance gemcitabine (G) and best supportive care (BSC) versus BSC, following standard combination therapy with gemcitabine-carboplatin (G-Cb) for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) . Abstract 7506Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(Suppl. 15) [Google Scholar]

- Berge & Doebele (2013).Berge EM, Doebele RC. Re-examination of maintenance therapy in non-small cell lung cancer with the advent of new anti-cancer agents. Drugs. 2013;73:517–532. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besse et al. (2014).Besse B, Adjei A, Baas P, Meldgaard P, Nicolson M, Paz-Ares L, Reck M, Smit EF, Syrigos K, Stahel R, Felip E, Peters S, Panel M. 2nd ESMO Consensus Conference on Lung Cancer: non-small-cell lung cancer first-line/second and further lines of treatment in advanced disease. Annals of Oncology. 2014;25:1475–1484. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodowicz et al. (2006).Brodowicz T, Krzakowski M, Zwitter M, Tzekova V, Ramlau R, Ghilezan N, Ciuleanu T, Cucevic B, Gyurkovits K, Ulsperger E, Jassem J, Grgic M, Saip P, Szilasi M, Wiltschke C, Wagnerova M, Oskina N, Soldatenkova V, Zielinski C, Wenczl M. Cisplatin and gemcitabine first-line chemotherapy followed by maintenance gemcitabine or best supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase III trial. Lung Cancer. 2006;52:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts et al. (2005).Butts C, Murray N, Maksymiuk A, Goss G, Marshall E, Soulieres D, Cormier Y, Ellis P, Price A, Sawhney R, Davis M, Mansi J, Smith C, Vergidis D, Ellis P, MacNeil M, Palmer M. Randomized phase IIB trial of BLP25 liposome vaccine in stage IIIB and IV non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:6674–6681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts et al. (2014).Butts C, Socinski MA, Mitchell PL, Thatcher N, Havel L, Krzakowski M, Nawrocki S, Ciuleanu TE, Bosquee L, Trigo JM, Spira A, Tremblay L, Nyman J, Ramlau R, Wickart-Johansson G, Ellis P, Gladkov O, Pereira JR, Eberhardt WE, Helwig C, Schroder A, Shepherd FA. Tecemotide (L-BLP25) versus placebo after chemoradiotherapy for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer (START): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2014;15:59–68. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai et al. (2015).Cai KC, Liu DG, Wang YY, Wu H, Huang ZY, Cai RJ, Wang HF, Xiong G, Zhang ZL. Gefitinib maintenance therapy in Chinese advanced-stage lung adenocarcinoma patients with EGFR mutations treated with prior chemotherapy. Neoplasma. 2015;62:302–307. doi: 10.4149/neo_2015_036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuzzo et al. (2010).Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, Cicenas S, Szczesna A, Juhasz E, Esteban E, Molinier O, Brugger W, Melezinek I, Klingelschmitt G, Klughammer B, Giaccone G. Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2010;11:521–529. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter et al. (2012).Carter DL, Garfield D, Hathorn J, Mundis R, Boehm KA, Ilegbodu D, Asmar L, Reynolds C. A randomized phase III trial of combined paclitaxel, carboplatin, and radiation therapy followed by weekly paclitaxel or observation for patients with locally advanced inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Clinical Lung Cancer. 2012;13:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childhood ALL Collaborative Group (1996).Childhood ALL Collaborative Group Duration and intensity of maintenance chemotherapy in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: overview of 42 trials involving 12 000 randomised children. Lancet. 1996;347:1783–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciuleanu et al. (2009).Ciuleanu T, Brodowicz T, Zielinski C, Kim JH, Krzakowski M, Laack E, Wu YL, Bover I, Begbie S, Tzekova V, Cucevic B, Pereira JR, Yang SH, Madhavan J, Sugarman KP, Peterson P, John WJ, Krejcy K, Belani CP. Maintenance pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care for non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2009;374:1432–1440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen et al. (2010a).Cohen MH, Cortazar P, Justice R, Pazdur R. Approval summary: pemetrexed maintenance therapy of advanced/metastatic nonsquamous, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Oncologist. 2010a;15:1352–1358. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen et al. (2010b).Cohen MH, Johnson JR, Chattopadhyay S, Tang S, Justice R, Sridhara R, Pazdur R. Approval summary: erlotinib maintenance therapy of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Oncologist. 2010b;15:1344–1351. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cufer, Ovcaricek & O’Brien (2013).Cufer T, Ovcaricek T, O’Brien ME. Systemic therapy of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: major-developments of the last 5-years. European Journal of Cancer. 2013;49:1216–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumville et al. (2012).Dumville JC, Soares MO, O’Meara S, Cullum N. Systematic review and mixed treatment comparison: dressings to heal diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetologia. 2012;55:1902–1910. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2558-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger et al. (2015).Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Akerley W, Bazhenova LA, Borghaei H, Camidge DR, Cheney RT, Chirieac LR, D’Amico TA, Demmy TL, Dilling TJ, Dobelbower MC, Govindan R, Grannis Jr FW, Horn L, Jahan TM, Komaki R, Krug LM, Lackner RP, Lanuti M, Lilenbaum R, Lin J, Loo Jr BW, Martins R, Otterson GA, Patel JD, Pisters KM, Reckamp K, Riely GJ, Rohren E, Schild SE, Shapiro TA, Swanson SJ, Tauer K, Yang SC, Gregory K, Hughes M. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 6. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2015;13:515–524. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidias et al. (2009).Fidias PM, Dakhil SR, Lyss AP, Loesch DM, Waterhouse DM, Bromund JL, Chen R, Hristova-Kazmierski M, Treat J, Obasaju CK, Marciniak M, Gill J, Schiller JH. Phase III study of immediate compared with delayed docetaxel after front-line therapy with gemcitabine plus carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:591–598. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaafar et al. (2011).Gaafar RM, Surmont VF, Scagliotti GV, Klaveren RJ, Papamichael D, Welch JJ, Hasan B, Torri V, Meerbeeck JP. A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III intergroup study of gefitinib in patients with advanced NSCLC, non-progressing after first line platinum-based chemotherapy (EORTC 08021/ILCP 01/03) European Journal of Cancer. 2011;47:2331–2340. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaccone et al. (2015).Giaccone G, Bazhenova LA, Nemunaitis J, Tan M, Juhasz E, Ramlau R, Van den Heuvel MM, Lal R, Kloecker GH, Eaton KD, Chu Q, Dunlop DJ, Jain M, Garon EB, Davis CS, Carrier E, Moses SC, Shawler DL, Fakhrai H. A phase III study of belagenpumatucel-L, an allogeneic tumour cell vaccine, as maintenance therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2015;51:2321–2329. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt et al. (2011).Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, Norris S, Falck-Ytter Y, Glasziou P, DeBeer H, Jaeschke R, Rind D, Meerpohl J, Dahm P, Schünemann HJ. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna et al. (2008).Hanna N, Neubauer M, Yiannoutsos C, McGarry R, Arseneau J, Ansari R, Reynolds C, Govindan R, Melnyk A, Fisher W, Richards D, Bruetman D, Anderson T, Chowhan N, Nattam S, Mantravadi P, Johnson C, Breen T, White A, Einhorn L. Phase III study of cisplatin, etoposide, and concurrent chest radiation with or without consolidation docetaxel in patients with inoperable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: the Hoosier Oncology Group and U.S. Oncology. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:5755–5760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández & Vázquez (2015).Hernández AM, Vázquez AM. Racotumomab-alum vaccine for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2015;14:9–20. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.984691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu et al. (2010).Hu X, Li GM, Wen SM, Ren DC, Bie J, Pan RQ. Evaluation of the clinical efficacy of maintenance chemotherapy for local advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Tumor. 2010;30:343–346. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson et al. (2013).Johnson BE, Kabbinavar F, Fehrenbacher L, Hainsworth J, Kasubhai S, Kressel B, Lin CY, Marsland T, Patel T, Polikoff J, Rubin M, White L, Yang JC, Bowden C, Miller V. ATLAS: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIIB trial comparing bevacizumab therapy with or without erlotinib, after completion of chemotherapy, with bevacizumab for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:3926–3934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson et al. (2008).Johnson EA, Marks RS, Mandrekar SJ, Hillman SL, Hauge MD, Bauman MD, Wos EJ, Moore DF, Kugler JW, Windschitl HE, Graham DL, Bernath Jr AM, Fitch TR, Soori GS, Jett JR, Adjei AA, Perez EA. Phase III randomized, double-blind study of maintenance CAI or placebo in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after completion of initial therapy (NCCTG 97-24-51) Lung Cancer. 2008;60:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karayama et al. (2013).Karayama M, Inui N, Kuroishi S, Yokomura K, Toyoshima M, Shirai T, Masuda M, Yamada T, Yasuda K, Suda T, Chida K. Maintenance therapy with pemetrexed versus docetaxel after induction therapy with carboplatin and pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized, phase II study. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2013;72:445–452. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly et al. (2008).Kelly K, Chansky K, Gaspar LE, Albain KS, Jett J, Ung YC, Lau DH, Crowley JJ, Gandara DR. Phase III trial of maintenance gefitinib or placebo after concurrent chemoradiotherapy and docetaxel consolidation in inoperable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: SWOG S0023. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:2450–2456. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima et al. (2009).Lima JP, Dos Santos LV, Sasse EC, Sasse AD. Optimal duration of first-line chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. European Journal of Cancer. 2009;45:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubarak et al. (2012).Mubarak N, Gaafar R, Shehata S, Hashem T, Abigeres D, Azim HA, El-Husseiny G, Al-Husaini H, Liu Z. A randomized, phase 2 study comparing pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus best supportive care as maintenance therapy after first-line treatment with pemetrexed and cisplatin for advanced, non-squamous, non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:423. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien et al. (2015).O’Brien ME, Gaafar R, Hasan B, Menis J, Cufer T, Popat S, Woll PJ, Surmont V, Georgoulias V, Montes A, Blackhall F, Hennig I, Schmid-Bindert G, Baas P. Maintenance pazopanib versus placebo in non-small cell lung cancer patients non-progressive after first line chemotherapy: a double blind randomised phase III study of the lung cancer group, EORTC 08092 (EudraCT: 2010-018566-23, NCT01208064) European Journal of Cancer. 2015;51:1511–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owonikoko, Ramalingam & Belani (2010).Owonikoko TK, Ramalingam SS, Belani CP. Maintenance therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: current status, controversies, and emerging consensus. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16:2496–2504. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz-Ares et al. (2013).Paz-Ares LG, De Marinis F, Dediu M, Thomas M, Pujol JL, Bidoli P, Molinier O, Sahoo TP, Laack E, Reck M, Corral J, Melemed S, John W, Chouaki N, Zimmermann AH, Visseren-Grul C, Gridelli C. PARAMOUNT: final overall survival results of the phase III study of maintenance pemetrexed versus placebo immediately after induction treatment with pemetrexed plus cisplatin for advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:2895–2902. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérol et al. (2012).Pérol M, Chouaid C, Pérol D, Barlési F, Gervais R, Westeel V, Crequit J, Léna H, Vergnenègre A, Zalcman G, Monnet I, Caer H, Fournel P, Falchero L, Poudenx M, Vaylet F, Ségura-Ferlay C, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Taron M, Milleron B. Randomized, phase III study of gemcitabine or erlotinib maintenance therapy versus observation, with predefined second-line treatment, after cisplatin-gemcitabine induction chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:3516–3524. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters et al. (2008).Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Contour-enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2008;61:991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2013). R Development Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Version 3.0.1. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi et al. (2014).Rossi A, Chiodini P, Sun J-M, O’Brien MER, Von Plessen C, Barata F, Park K, Popat S, Bergman B, Parente B, Gallo C, Gridelli C, Perrone F, Di Maio M. Six versus fewer planned cycles of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. The Lancet Oncology. 2014;15:1254–1262. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salanti et al. (2008).Salanti G, Higgins JP, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Evaluation of networks of randomized trials. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2008;17:279–301. doi: 10.1177/0962280207080643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salles et al. (2011).Salles G, Seymour JF, Offner F, Lopez-Guillermo A, Belada D, Xerri L, Feugier P, Bouabdallah R, Catalano JV, Brice P, Caballero D, Haioun C, Pedersen LM, Delmer A, Simpson D, Leppa S, Soubeyran P, Hagenbeek A, Casasnovas O, Intragumtornchai T, Ferme C, Da Silva MG, Sebban C, Lister A, Estell JA, Milone G, Sonet A, Mendila M, Coiffier B, Tilly H. Rituximab maintenance for 2 years in patients with high tumour burden follicular lymphoma responding to rituximab plus chemotherapy (PRIMA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:42–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, Miller & Jemal (2016).Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socinski et al. (2014).Socinski MA, Wang XF, Baggstrom MQ, Gu L, Stinchcombe TE, Edelman MJ, Baker JR S, Mannuel HD, Crawford J, Vokes EE. Sunitinib (S) switch maintenance in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): an ALLIANCE (CALGB 30607), randomized, placebo-controlled phase III trial . Abstract 8040Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(suppl 15) [Google Scholar]

- Tan et al. (2015).Tan PS, Lopes G, Acharyya S, Bilger M, Haaland B. Bayesian network meta-comparison of maintenance treatments for stage IIIb/IV non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with good performance status not progressing after first-line induction chemotherapy: results by performance status, EGFR mutation, histology and response to previous induction. European Journal of Cancer. 2015;51:2330–2344. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney et al. (2007).Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veroniki et al. (2013).Veroniki AA, Vasiliadis HS, Higgins JP, Salanti G. Evaluation of inconsistency in networks of interventions. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;42:332–345. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westeel et al. (2005).Westeel V, Quoix E, Moro-Sibilot D, Mercier M, Breton JL, Debieuvre D, Richard P, Haller MA, Milleron B, Herman D, Level MC, Lebas FX, Puyraveau M, Depierre A. Randomized study of maintenance vinorelbine in responders with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97:499–506. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods, Hawkins & Scott (2010).Woods BS, Hawkins N, Scott DA. Network meta-analysis on the log-hazard scale, combining count and hazard ratio statistics accounting for multi-arm trials: a tutorial. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2010;10:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan et al. (2012).Yuan DM, Wei SZ, Lv YL, Zhang Y, Miao XH, Zhan P, Yu LK, Shi Y, Song Y. Single-agent maintenance therapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chinese Medical Journal. 2012;125:3143–3149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2015).Zhang C, Huang C, Wang J, Wang X, Li K. Maintenance or consolidation therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis involving 5841 subjects. Clinical Lung Cancer. 2015;16:e15–e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2012).Zhang L, Ma S, Song X, Han B, Cheng Y, Huang C, Yang S, Liu X, Liu Y, Lu S, Wang J, Zhang S, Zhou C, Zhang X, Hayashi N, Wang M. Gefitinib versus placebo as maintenance therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (INFORM; C-TONG 0804): a multicentre, double-blind randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13:466–475. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao et al. (2015).Zhao H, Fan Y, Ma S, Song X, Han B, Cheng Y, Huang C, Yang S, Liu X, Liu Y, Lu S, Wang J, Zhang S, Zhou C, Wang M, Zhang L. Final overall survival results from a phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of gefitinib versus placebo as maintenance therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (INFORM; C-TONG 0804) Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2015;10:655–664. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou et al. (2015).Zhou F, Jiang T, Ma W, Gao G, Chen X, Zhou C. The impact of clinical characteristics on outcomes from maintenance therapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2015;89:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data has been supplied as a Supplementary File.