Abstract

Background

Intra-arterial thrombolysis (IAT) for the treatment of acute central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) has demonstrated variable results for improving visual acuity and remains controversial. Despite limited evidence, time from symptom onset to thrombolysis is believed to be an important factor in predicting visual improvement after IAT.

Methods

A comprehensive review of the literature was conducted and individual subject level data were extracted from relevant studies. From these, a secondary analysis was performed. Initial and final logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) scores were either abstracted directly from relevant studies or converted from provided Snellen chart scores. Change in logMAR scores was used to determine overall treatment efficacy.

Results

Data on 118 patients undergoing IAT from five studies were evaluated. Median logMAR improvement in visual acuity was −0.400 (p < 0.001). There was no significant association between logMAR change and time to treatment when time (hours) was described as a continuous variable or described categorically [0–4, 4–8, 8–12, 12+ h; or 0–6, 6–12, 12+ h].

Conclusion

The visual improvement observed in this series had no relationship to the time from symptom onset to treatment with IAT. This suggests that patients may have the possibility for improvement even with delayed presentation to the neurointerventionalist. Other factors, such as completeness of retinal occlusion, may be more important than time to treatment. Additional studies to determine optimal patient selection criteria for the endovascular treatment of acute CRAO are needed.

Key Words: Central retinal artery occlusion, Fibrinolysis, Infusions, Intra-arterial thrombolysis, Therapeutic thrombolysis, Time to treatment

Introduction

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is a rare ophthalmologic emergency that may ultimately result in complete vision loss of the affected eye. Despite the historic use of noninvasive standard therapies in the treatment of acute nonarteritic CRAO, recent studies have demonstrated little advantage to their use compared with the natural disease course [1, 2, 3]. Research into the utilization of thrombolytic therapy for the treatment of CRAO has been ongoing for over 20 years and has included intravenous and intra-arterial routes of administration [4, 5]. Though the intravenous use is less invasive, the use of intra-arterial thrombolysis (IAT) by selective catheterization of the ophthalmic artery ostia with a microcatheter has garnered interest due to its ability to minimize systemic complications and theoretically increase the time to treatment therapeutic window.

Retina is neural tissue, thereby allowing CRAO to be pathophysiologically compared to acute ischemic stroke (AIS). Unlike in AIS, the benefit in outcomes associated with minimizing time from symptom onset to revascularization has not been firmly established for CRAO [6]. Animal models have demonstrated that irreversible retinal ischemia may occur in as little as 105 min after total occlusion [7]. While many experts agree that a temporal relationship between revascularization and visual outcomes most likely exists, studies have inconsistently demonstrated this relationship. Concerns exist regarding the quality of a negative previous randomized controlled trial designed to assess the efficacy of IAT where the times to thrombolysis were significantly greater than what would be acceptable in the treatment of AIS [8]. In this study, we performed a systematic literature review of IAT treatment for CRAO and extracted individual subject level data to analyze the relationship between improvement in visual acuity outcomes and time to treatment in the existing literature. Through this method, we provide the largest study ever conducted examining the effect of time to thrombolysis on visual outcomes after CRAO.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in MEDLINE and EMBASE for studies utilizing IAT in the treatment of CRAO. MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched from January 1, 1946 to January 1, 2015. Key words included ‘retinal artery’, ‘intra-arterial fibrinolysis’, ‘intra-arterial thrombolysis’, and ‘intraarterial thrombolytic’. Each title was subsequently reviewed for relevance and only English language studies were evaluated. Additionally, the reference section of each study was reviewed to identify additional relevant studies that may have been missed with the initial search. We avoided duplication of patient data by examining authors with multiple published studies evaluating CRAO patients. We selected data from their newest study to avoid the possibility that a prior publication may have contained a smaller series of an older subset of the same patients. Inclusion criteria consisted of acute-onset nonarteritic CRAO; IAT with either urokinase (FDA off-label) or recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (FDA off-label), and studies containing individual patient data on initial visual acuity, final visual acuity, and time from symptom onset to treatment. From these studies, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) scores were either abstracted directly from provided data or converted from Snellen chart scores that had been provided. Lower logMAR scores represent better visual acuity. Values for profoundly low visual acuity scores were subsequently converted to a logMAR scale in accordance with the technique described by Lange et al. [9]. Mercier et al. [10] included a profoundly low visual acuity choice of ‘see steady hand’ that was not quantified by Lange et al. A logMAR score equal to 2.13 was chosen to quantify this option as it represented a profoundly low visual acuity ranging between counting fingers (logMAR = 1.98) and hand movement (logMAR = 2.28).

A Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed on initial and final logMAR scores to evaluate for treatment efficacy. A nonparametric ANOVA and linear regression analysis were conducted to evaluate the relationship between time to thrombolysis and change in visual outcomes. Intervals for distinct ANOVAs included: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 12+ h] and [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 12+ h]. A linear regression analysis was conducted to assess the correlation between time (hours) and change in logMAR. Both natural log and log10 transformations were utilized to assess for existence of correlation. A p value cutoff of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance for all data analyses. All statistical analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.3.

Results

The comprehensive literature search produced five studies satisfying all inclusion criteria. The study publication dates ranged from 1992 to 2013 and subject level data were obtained for 118 patients (table 1) [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Another study conducted by Framme et al. [15] was also identified; however, due to a language barrier, it was omitted from this study. While other relevant studies were identified, these did not include patient level data and thus were not included in our analysis [16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Of the patients examined, 75.7% (87/118) were male with an average age of 63.2 years (SD 14.1). The mean and median time from symptom onset to IAT was 12.4 h (SD 10.4) and 9 h (IQR 6.9–12), respectively. Fibrinolytic agents utilized included recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in 93 patients and urokinase in 25 patients.

Table 1.

Studies fulfilling all inclusion criteria

| First author [Ref.], year | Study type | Total patients | Average time from symptom onset to treatment, h | Agent | Timing of post IAT BCVA examination | Coexisting arterial occlusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercier 10, 2014 | Retrospective case series | 14 | 8.0 [4.5–17.0] |

tPA Mean: 35 mg, SD 13 |

6–12 months | None specified |

|

| ||||||

| Pettersen 11, 2005 | Retrospective case series | 6 | 9.7 [6.0–18.0] |

tPA Range: 10–30 mg |

2 days to 2.5 years | None specified |

|

| ||||||

| Butz 12, 2003 | Retrospective case series | 22 | 7.6 [4.0–11.0] |

Urokinase Mean: 642,000,SD 300K OR tPA Mean: 27 mg, SD 8 |

Not specified | Severe ICA stenosis (1) ICA occlusion (1) |

|

| ||||||

| Richard 13, 1999 | Retrospective case series | 53 | 14.0 [3.0–50.0] |

tPA Maximum: 40 mg |

3 months | None specified |

|

| ||||||

| Schumacher 14, 1993 | Retrospective case series | 23 | 15.4 [3.833–60.0] |

Urokinase Maximum: 1.2 million units OR tPA Maximum: 70 mg |

Immediately to 6 months | ICA occlusion (4) ICA stenosis (4) MCA occlusion (1) |

BCVA = Best corrected visual acuity; tPA = tissue plasminogen activator; K = thousand; ICA = internal carotid artery.

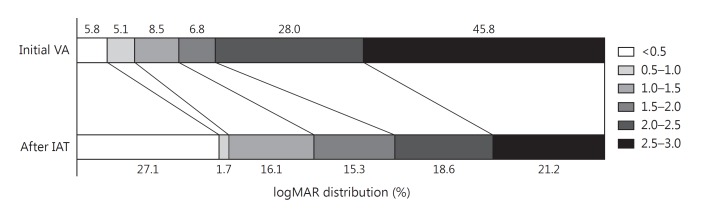

Initial visual acuity assessment demonstrated that 73.8% of patients presented with a visual acuity logMAR score of 2.0 or worse. After IAT treatment, this improved dramatically to 39.8% having a visual acuity of 2.0 or worse. Additionally, only 10.9% of patients had an initial visual acuity of <1.0 on presenting assessment; however, this improved to 28.8% after IAT (fig. 1). Mean logMAR improvement for all patients studied was −0.61 (SD 0.68). A Shapiro-Wilk normality test demonstrated that logMAR scores were not normally distributed (p < 0.0001). A Wilcoxon signed rank test was subsequently conducted demonstrating a significant median improvement in visual acuity of −0.400 (IQR 0–1.06) logMAR (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Shift diagram demonstrating initial and final logMAR score distributional improvement in visual acuity (VA).

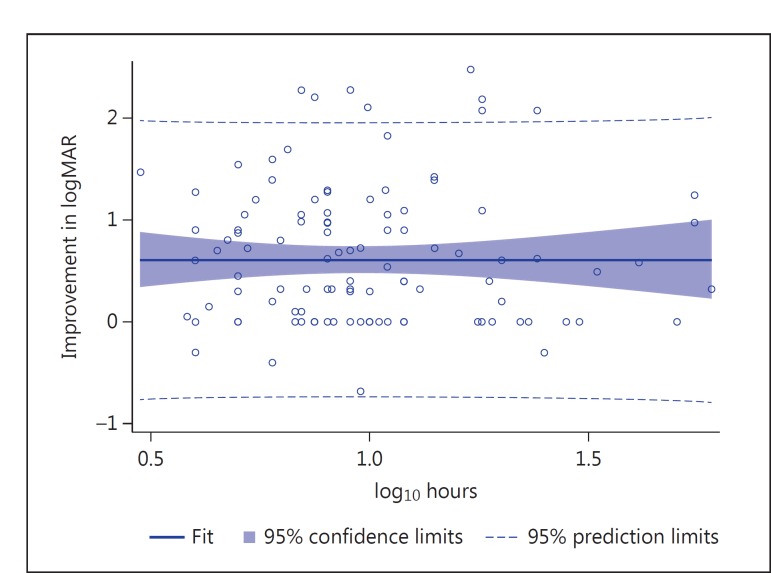

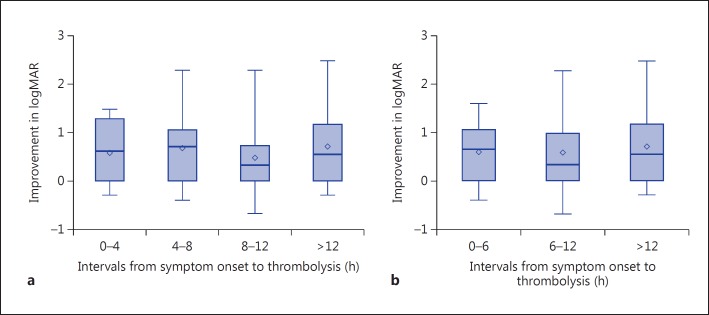

A scatter plot of individual patients’ improvement in logMAR versus log10 hours from symptom onset to treatment is provided in figure 2. Linear regression analysis results demonstrated no significant correlation between time to thrombolysis and improvement in logMAR using either natural log or log10 transformations for hours (p = 0.99, R2 = 0 for each). For the purpose of exploratory analysis, two ordinal intervals were examined including [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 12+] (table 2) and [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 12+] (table 3) hour intervals. Mean change in logMAR was found to be largest in the 12+-hour time interval, with an improvement of −0.700 logMAR. The smallest mean improvement in logMAR occurred in the 8- to 12-hour time interval (–0.484) (fig. 3). Nonparametric ANOVA demonstrated no temporal relationship with change in logMAR for the [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 12+] or [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 12+] hour intervals examined (p = 0.546, F = 0.71 and p = 0.721, F = 0.33, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot and fit for regression of change in logMAR with hours to treatment (log10 scale). Data points represent individual patient improvement in logMAR (n = 118). Improvement in logMAR score represents improvement in visual acuity.

Table 2.

ANOVA of change in logMAR and 4-hour time intervals

| Change in logMAR | 4-Hour intervals |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total (n = 118) | 0–4 (n = 7) | 4–8 (n = 45) | 8–12 (n = 38) | >12 (n = 28) | |

| Mean (95% CI) | −0.610 (−0.732, −0.489) | −0.572 (−1.077, −0.068) | −0.667 (−0.855, −0.479) | −0.484 (−0.686, −0.283) | −0.700 (−0.988, −0.412) |

|

| |||||

| Median (min, max) | −0.400 (−2.478, 0.680) | −0.602 (−1.475, 0.301) | −0.700 (−2.280, 0.400) | −0.359 (−2.280, 0.680) | −0.538 (−2.478, 0.301) |

Change in logMAR equals follow-up minus initial. Larger absolute value negative numbers equal greater visual improvement; larger absolute value positive numbers equal greater visual worsening. p = 0.546.

Table 3.

ANOVA of change in logMAR and 6-hour time intervals

| Change in logMAR | 6-Hour intervals |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| total (n = 118) | 0–6 (n = 26) | 6–12 (n = 64) | >12 (n = 28) | |

| Mean (95%CI) | −0.610 (−0.732, −0.489) | −0.577 (−0.809, −0.346) | −0.605 (−0.767, −0.443) | −0.700 (−0.988, −0.412) |

|

| ||||

| Median (min, max) | −0.400 (−2.478, 0.680) | −0.651 (−1.600, 0.400) | −0.320 (−2.280, 0.680) | −0.538 (−2.478, 0.301) |

Change in logMAR equals follow-up minus initial. Larger absolute value negative numbers equal greater visual improvement; larger absolute value positive numbers equal greater visual worsening. p = 0.721.

Fig. 3.

Standard box plots of logMAR distributions among 4-hour (a) and 6-hour (b) time intervals demonstrating no significant difference in logMAR distribution between groups.

Complications were observed in 11 of the cases examined (9.3%). Seven thromboembolic complications were noted including 2 occurring during catheter manipulation, 3 transient ischemic events, 1 minor stroke, and 1 major stroke. Of these ischemic events, 6 resolved in the same session with use of IAT. Other complications included 1 intracranial hemorrhage, 1 femoral artery access hematoma, and 1 hypertensive crisis. In 1 case, the patient experienced pain on urokinase injection, which quickly resolved. Long-term morbidity occurred in 1 case resulting from a major stroke.

Discussion

The prognosis of CRAO is considered dismal, with some studies reporting as few as 8% experiencing a recovery in visual acuity with the use of noninvasive (conservative) standard therapy [16]. While research into the use of IAT for the treatment of CRAO has been ongoing for over 20 years, results continue to be highly variable and there is no consensus on its efficacy. Though many controlled cohort studies have demonstrated a significant improvement in visual acuity after IAT, these publications likely suffer from patient selection bias. Likewise, the overall literature likely suffers from publication bias in favor of IAT therapy as negative studies tend not to be submitted and/or selected for publication. A single recent randomized clinical trial by Schumacher etal. [19] (EAGLE study) demonstrated no significant improvement in visual outcomes after IAT compared with those treated with conservative therapy [16, 17, 18, 19]. Due to this variability in the existing literature, determination of the optimal patient selection criteria for IAT that may allow for the demonstration of efficacy in randomized controlled trials is an active area of investigation. Influences including time from symptom onset to fibrinolysis and degree of arterial occlusion and dosing regimen are being explored as potential major factors that may correlate with final visual outcomes after IAT. Time to thrombolysis has inconsistently been demonstrated to have an influence on visual outcomes in existing studies; however, expert opinion appears to strongly favor it playing a prominent role in final visual acuity after IAT due to the similarities between CRAO and AIS [8, 12, 18].

In our study, a pooled population of 118 patients representing five separate studies demonstrated a significant improvement in visual acuity after treatment with IAT. Due to the typical selection and publication bias mentioned above, the overall improvement with IAT seen in this study represents a weak level of evidence supporting IAT, and it is not the focus of this study. The key finding of this study is that in this subset of patients who happen to have an overall significant visual improvement after IAT, there was no correlation between that visual improvement and time to IAT treatment (fig. 2). In fact, this study demonstrates that patients can make significant visual improvement even when IAT is performed more than 12 h after symptom onset.

The results of this study seem to directly contradict the current belief that improvement in visual acuity directly correlates with shorter time to thrombolytic therapy [17, 18, 20]. In a recent study by Schmidt et al. [20], 62 patients were evaluated after treatment with IAT and found that patients treated in less than 6 h were more likely to experience a distinct improvement in visual acuity compared with those treated after 6 h (30.77 vs. 11.13%, respectively). Additionally, other previously published studies have demonstrated a correlation between time to thrombolysis and visual outcomes among patients treated within 6 h [17, 18, 20]. Studies conducted by Weber et al. [18] and Arnold et al. [17] treated patients in 4.2 and 3.68 h on average, respectively. Both studies demonstrated very positive results. Results from Weber et al. [18] showed that 65% of patients treated with IAT had at least some improvement in visual acuity compared with only 33% in the control group. In our study, 26 patients were treated in less than 6 h. Of these 22 patients, a mean visual change of −0.577 logMAR was observed compared with a −0.605 and −0.700 logMAR change in the 6- to 12-hour and 12+-hour intervals, respectively. This difference was not found to be significant (p = 0.72).

In our study, the largest improvement in visual acuity occurred in patients treated 12 h after symptom onset; however, this finding was not statistically significant. Due to the small sample size in the 0- to 4-hour group, it is impossible to conclude from our study, if patients treated in this time window would have had better visual outcomes compared to other treatment times. It is possible that if a significant amount of data were to be collected on patients treated very early (much less than 4 h), it may be possible to see a time effect on visual outcomes. Interestingly, Arnold et al. [17] reported that best visual outcomes occurred in patients treated in less than 4 h. Unfortunately, hyper-early time to IAT treatment is difficult to implement and numerous logistical issues exist which are being experienced with current neuroendovascular treatment of large-vessel occlusion AIS.

Nevertheless, our study convincingly demonstrates that while no correlation between time to fibrinolysis and improvement in vision existed at any time point as demonstrated by linear regression (p = 0.99, R2 = 0 for each), visual improvement after IAT was certainly possible within the longer time to treatment windows despite the overall poor prognosis reported for CRAO. It is likely that after some hyper-early time threshold from symptom onset, other factors wield a much greater influence than time on whether an individual patient will improve after IAT therapy. Exploring what these potential influential factors may be should be the focus of future research.

CRAO may manifest as incomplete, subtotal, or total occlusion, and may be differentiated by angiography or fundoscopic findings. Degree of CRAO has been proposed as an important factor in the efficacy of IAT to improve visual outcomes. One study by Ahn et al. [16] demonstrated that patients with incomplete occlusion, compared with total, experienced a significantly higher rate of clinically significant visual improvement, i.e. 76.9 versus 0%, respectively. These results echoed a 2002 study by Schmidt et al. [20] which showed that 50% of patients who underwent IAT for incomplete occlusion had a distinct improvement in visual acuity compared to 0% of patients with a total occlusion. Unfortunately, the individual patient data available in our study did not include assessments for the level of occlusion due to limited availability within included studies. Future studies should further examine this correlation and its inclusion in result analysis should always be considered. It is possible with the utilization of fundoscopy, or superselective angiography, that the identification and selective treatment of patients with incomplete or subtotal retinal artery occlusion could lead to the demonstration of the overall efficacy of IAT in future randomized controlled trials irrespective of time to treatment. Establishing the importance of factors such as this could help increase the potential treatment effect of IAT and decrease the sample size necessary for properly powered clinical trials while limiting cases where treatment with IAT is most certainly futile.

The only randomized controlled trial conducted to date concluded that IAT is ineffective in the treatment of CRAO [19]; however, several experts have expressed concerns regarding its validity. Concerns regarding this study have included a severely delayed time to thrombolysis, nonoptimal inclusion/exclusion criteria, and improper methods of blinding [8, 19, 21]. Specifically, important inclusion criteria such as baseline brain imaging and a thorough neurological exam at presentation were not utilized and may have directly influenced study results [21]. In order to prevent these concerns in future studies, further research must be conducted into the most influential factors on outcome after IAT. Our study suggests a less important role for time to thrombolysis in the treatment of CRAO. Additional study into time to treatment may be necessary prior to forcing arbitrary time-to-treatment requirements on the inclusion and exclusion criteria for future randomized controlled trials in the treatment of CRAO.

In addition to questions regarding time to treatment, the vast majority of studies evaluating the use of IAT for CRAO do not provide any method for confirming that recanalization has occurred. Visualization of the central retinal artery during catheter angiography is difficult; therefore, further study into techniques to confirm reperfusion would be beneficial to better define treatment efficacy and minimize the use of thrombolytic agents. Some studies have suggested halting infusion of thrombolytic agents when a rapid improvement of visual acuity occurs or when flow through the retinal and choroidal vessels significantly increase [14]. Fluorescein angiography, as the accepted gold standard for evaluating the retinal circulation, has been utilized in a number of studies as a method of confirming retinal reperfusion [16]. Regardless of the method utilized, we recommend future studies to utilize some kind of method of evaluating if recanalization has occurred.

Though our study performed a secondary analysis of actual individual patient data and represents the largest series to evaluate time to IAT treatment for CRAO, limitations to this study exist. As previously mentioned, selection bias and publication bias should always be considered when a large number of uncontrolled outcome studies are utilized for data extraction. However, these biases have minimal influence over the time to treatment data presented here compared to the overall question of whether IAT therapy is efficacious in all CRAO patients. Additionally, the low sample size of patients treated in less than 4 h is a weakness of this study making it difficult to determine if outcomes are more positive in patients treated in less than 4 h of symptom onset. This weakness is muted somewhat by the understanding that real-world logistical issues make treatment less than 4 h after symptom onset difficult and likely impossible for most CRAO patients. Additionally, the exact technique of IAT utilized varied within studies and between studies making direct comparisons difficult. While no obvious correlation between visual outcomes and any specific technique was apparent, we also recommend a formal investigation into the efficacy of the various techniques to better direct future research.

Conclusion

Acute CRAO is a rare, orphaned disease that has a dismal prognosis with standard noninvasive therapy, and potential advances in treatment have not proven to be efficacious. The impressive visual improvement observed in this series had no relationship to the time from symptom onset to treatment with IAT. This suggests that patients may have the possibility for improvement even with delayed presentation to the neuroendovascular specialist. Other factors, such as completeness of retinal occlusion, may be more important than time to treatment. Additional study to determine optimal patient selection criteria for the endovascular treatment of acute CRAO is needed. Focused attention on very early times to treatment (less than 4 h) may be warranted but difficult. In the future, if neuroendovascular treatment of properly selected CRAO patients is found to be efficacious, neuroendovascular specialists should be well positioned to offer this treatment given the recent focus on improving systems of care for the endovascular treatment of large-vessel occlusion AIS.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Augsburger JJ, Magargal LE. Visual prognosis following treatment of acute central retinal artery obstruction. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980;64:913–917. doi: 10.1136/bjo.64.12.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atebara NH, Brown GC, Cater J. Efficacy of anterior chamber paracentesis and Carbogen in treating acute nonarteritic central retinal artery occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:2029–2034. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30758-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller AJ, Neubauer AS, Schaller U, Kampik A. Evaluation of minimally invasive therapies and rationale for a prospective randomized trial to evaluate selective intra-arterial lysis for clinically complete central retinal artery occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1377–1381. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.10.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Annonier P, Sahel J, Wenger JJ, Rigolot JC, Foessel M, Bronner A. Local fibrinolytic treatment in occlusions of the central retinal artery. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1984;7:711–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CS, Lee AW, Campbell B, Lee T, Paine M, Fraser C, Grigg J, Markus R. Efficacy of intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator in central retinal artery occlusion: report from a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke. 2011;42:2229–2234. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khatri P, Yeatts SD, Mazighi M, Broderick JP, Liebeskind DS, Demchuk AM, Amarenco P, Carrozzella J, Spilker J, Foster LD, Goyal M, Hill MD, Palesch YY, Jauch EC, Haley EC, Vagal A, Tomsick TA. Time to angiographic reperfusion and clinical outcome after acute ischemic stroke: an analysis of data from the Interventional Management of Stroke (IMS III) phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:567–574. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70066-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayreh SS, Kolder HE, Weingeist TA. Central retinal artery occlusion and retinal tolerance time. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:75–78. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayreh SS. Comment re: multicenter study of the European Assessment Group for Lysis in the Eye (EAGLE) for the treatment of central retinal artery occlusion: design issues and implications. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245:464–466. doi: 10.1007/s00417-006-0473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lange C, Feltgen N, Junker B, Schulze-Bonsel K, Bach M. Resolving the clinical acuity categories ‘hand motion’ and ‘counting fingers’ using the Freiburg Visual Acuity Test (FrACT) Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:137–142. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0926-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercier J, Kastler A, Jean B, Souteyrand G, Chabert E, Claise B, Pereira B, Gabrillargues J. Interest of local intraarterial fibrinolysis in acute central retinal artery occlusion: clinical experience in 16 patients. J Neuroradiol. 2015;42:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pettersen JA, Hill MD, Demchuk AM, Morrish W, Hudon ME, Hu W, Wong J, Barber PA, Buchan AM. Intraarterial thrombolysis for retinal artery occlusion: the Calgary experience. Can J Neurol Sci. 2005;32:507–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butz B, Strotzer M, Manke C, Roider J, Link J, Lenhart M. Selective intraarterial fibrinolysis of acute central retinal artery occlusion. Acta Radiol. 2003;44:680–684. doi: 10.1080/02841850312331287829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richard G, Lerche RC, Knospe V, Zeumer H. Treatment of retinal arterial occlusion with local fibrinolysis using recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:768–773. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schumacher M, Schmidt D, Wakhloo AK. Intra-arterial fibrinolytic therapy in central retinal artery occlusion. Neuroradiology. 1993;35:600–605. doi: 10.1007/BF00588405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Framme C, Spiegel D, Roider J, Sachs HG, Lohmann CP, Butz B, Link J, Gabel VP. Central retinal artery occlusion. Importance of selective intra-arterial fibrinolysis. Ophthalmologe. 2001;98:725–730. doi: 10.1007/s003470170079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn SJ, Kim JM, Hong JH, Woo SJ, Ahn J, Park KH, Han MK, Jung C. Efficacy and safety of intra-arterial thrombolysis in central retinal artery occlusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:7746–7755. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold M, Koerner U, Remonda L, Nedeltchev K, Mattle HP, Schroth G, Sturzenegger M, Weber J, Koerner F. Comparison of intra-arterial thrombolysis with conventional treatment in patients with acute central retinal artery occlusion. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:196–199. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.037135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber J, Remonda L, Mattle HP, Koerner U, Baumgartner RW, Sturzenegger M, Ozdoba C, Koerner F, Schroth G. Selective intra-arterial fibrinolysis of acute central retinal artery occlusion. Stroke. 1998;29:2076–2079. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.10.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schumacher M, Schmidt D, Jurklies B, Gall C, Wanke I, Schmoor C, Maier-Lenz H, Solymosi L, Brueckmann H, Neubauer AS, Wolf A, Feltgen N. Central retinal artery occlusion: local intra-arterial fibrinolysis versus conservative treatment, a multicenter randomized trial. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1367–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt DP, Schulte-Monting J, Schumacher M. Prognosis of central retinal artery occlusion: local intraarterial fibrinolysis versus conservative treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:1301–1307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arthur A, Aaron S. Thrombolysis for artery occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:604–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]