Abstract

Background

Central nervous system vasculitis (CNSV) is a rare disorder, the pathophysiology of which is not fully understood. It involves a combination of inflammation and thrombosis. CNSV is most commonly associated with headache, gradual changes in mental status, and focal neurological symptoms. Diagnosis requires the effective use of history, laboratory testing, imaging, and biopsy. Catheter angiography can be a powerful tool in the diagnosis when common and low-frequency angiographic manifestations of CNSV are considered. We review these manifestations and their place in the diagnostic algorithm of CNSV.

Summary

We reviewed the PubMed database for case series of CNSV that included 5 or more patients. Demographic and angiographic findings were collected. Angiographic findings were dichotomized between common and low-frequency findings. A system for incorporating these findings into clinical decision-making is proposed.

Key Message

CNSV is a diagnostic challenge due to the absence of a true gold standard test. In the absence of such a test, catheter angiography remains a central piece of the diagnostic puzzle when appropriately employed and interpreted.

Key Words: Primary central nervous system vasculitis, Vasculitis, Angiitis, Angiography

Introduction

Inflammatory disorders of the vascular system were first described in the mid-1800s when Kussmaul and Maier [1] coined the term ‘periarteritis nodosa’ to describe a disease with severe leg cramping and widespread vascular inflammation at autopsy. Within two decades, this term had evolved into its current form, ‘polyarteritis nodosa’ (PAN) [2], and peripheral nerve involvement was recognized as the primary neurological manifestation. By the mid-1900s, it became clear that a variety of distinct clinical and pathological syndromes were being lumped under the PAN heading, and distinct eponyms for these systemic vasculitides emerged [3] (table 1).

Table 1.

Vasculitides

| Disorder | Vessels affected | Epidemiology | Histology | Clinical features | Biomarkers | Incidence of CNS involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takayasu's arteritis | Large | Young Asian women | Granulomatous | Limb claudication, diminished pulses, visual defects, stroke | None | 10–36% |

|

| ||||||

| Giant-cell arteritis | Large | Adults >50 years of age | Granulomatous | Temporal headache, jaw claudication, blindness, stroke | Elevated ESR/CRP | <2% |

|

| ||||||

| Polyarteritis nodosa | Medium | Men > women; age 40–60 years | Necrotizing | Skin ulcers, MI, renal failure, ICH | Elevated ESR/CRP | 20–40% |

|

| ||||||

| Kawasaki disease | Medium | Children <4 years, M > F, Asian | Necrotizing | Lymphadenopathy, mucocutaneous involvement – mouth, hands, and feet | Anti-endothelial antibodies, cardiac enzyme elevation | Unknown |

|

| ||||||

| Churg-Strauss syndrome | Medium | Women > men; age 40–60 years | Necrotizing | Asthma, sinusitis, MI, stroke | Eosinophils >10% of diffl.; positive P-ANCA (50%) and positive C-ANCA (25%) titers, eosinophilic-rich granulomata | 15% |

|

| ||||||

| Wegner's granulomatosis | Small | Men > women; age 40–50 years | Necrotizing | Nasal ulcers, corneal ulcers, GN, stroke | C-ANCA | 10% |

|

| ||||||

| Microscopic polyangiitis | Small | Men > women; age 40–60 years | Necrotizing | Pulmonary hemorrhages, GN, stroke | Positive P-ANCA titers with myeloperoxidase specificity | Unknown |

|

| ||||||

| Behçet's disease | Venous | ‘Silk road’ populations | Venous | Mucosal ulcers (oral and genital), uviitis, cerebral vein thromobosis | Positive pathergy test | – |

|

| ||||||

| Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis | Small | Women > men; age 40–50 years | Leukocytoclastic | Palpable purpura, cutaneous infarctions, CNS involvement is rare | Elevated cryoglobulins, low C4 complement | Unknown |

|

| ||||||

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Small | Children and young adults; boys > girls | Leukocytoclastic | Palpable purpura, polyarthritis, GN | Elevated IgA levels, ESR, and CRP | Unknown |

ICH = Intracranial hemorrhage; MI = myocardial infarction; GN = glomerulonephritis; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP = C-reactive protein; diffl. = differential.

Among the early attempts to distinguish the different vasculitides were two case reports by Harbitz [4] of ‘unknown forms of arteritis’ that primarily affected the central nervous system (CNS). Thirty years later, several similar cases were described by Newman and Wolf [5] and termed noninfectious granulomatous angiitis involving the CNS (GACNS). Cravioto and Feigin [6] argued that GACNS was a distinct form of vasculitis with a predilection for the CNS and not a variant of PAN or some other forms of vasculitis. The synonyms for GACNS are numerous (table 2), with conventional usage changing over time. The term ‘primary angiitis of the CNS’ is now commonly used as is ‘primary CNS vasculitis’ (PCNSV) [7, 8]. We will utilize the latter term in this article. The following diagnostic criteria for PCNSV were proposed by Calabrese and Mallek [7] in 1988, and have been widely relied upon since that time: (1) a history or clinical findings of an acquired neurologic deficit, which remained unexplained after a thorough initial basic evaluation; (2) these patients demonstrated either classic angiographic or histopathologic features of angiitis within the CNS, and (3) there was no evidence of systemic vasculitis or of any other condition to which the angiographic or pathologic features could be secondary.

Table 2.

Primary CNSV naming conventions

| First author [Ref.], year | Name |

|---|---|

| Newman 5, 1952 | Noninfectious granulomatous angiitis involving the CNS |

| Cravioto 6, 1959 | Noninfectious granulomatous angiitis with predilection for the nervous system |

| Hughes 55, 1966 | Granulomatous giant cell angiitis of the CNS |

| Kolodny 56, 1968 | Granulomatous angiitis of the CNS |

| Snyder 57, 1978 | Isolated benign cerebral vasculitis |

| Valvanis 58, 1979 | Cerebral granulomatous angiitis |

| Cupps 9, 1983 | Isolated angiitis of the CNS |

| Calabrese 7, 1988 | Primary angiitis of the CNS |

| Salvarani 8, 2007 | Primary CNS vasculitis |

From the first descriptions in the 1950s through the 1970s, most cases of PCNSV were diagnosed postmortem at autopsy and the disease was believed to be generally fatal [7]. However, in 1983, Cupps et al. [9] described several therapeutic successes that relied on steroid and immunosuppressive regimens. In 1988, Call and Flemming [10], under the supervision of C. Miller Fisher, described a reversible vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) that had previously been seen as a variant of PCNSV but is in fact a distinct clinical entity with a more ‘benign’ clinical course that does not require immunosuppressive treatment. RCVS is now thought to be inclusive of a number of disorders: Call-Fleming syndrome; benign angiopathy of the CNS; postpartum angiopathy; thunderclap headache with reversible vasospasm; migrainous vasospasm or migrainous angiitis, and drug-induced cerebral arteritis or angiopathy [11] (table 3).

Table 3.

Major differences distinguishing PCNSV from RCVS 11

| PCNSV | RCVS | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient demographics | M > F; >50 years old | F >> M; 20–50 years old |

|

| ||

| Neurological impairment | Diffuse, encephalopathy | Focal |

|

| ||

| Headache character | Insidious, chronic | Recurrent, thunderclap |

|

| ||

| Infarct pattern | Small, scattered | Watershed |

|

| ||

| Lobar hemorrhage | Very rare | Common |

|

| ||

| Cortical subarachnoid hemorrhage | Very rare | Common |

|

| ||

| CSF findings | Elevated protein, mild elevation in WBCs | Normal |

|

| ||

| Angiography | Irregular, notched ectasia, changes often chronic | ‘Sausage on a string’ sign, resolves <12 weeks |

The role of angiography in the diagnosis of PCNSV emerged in the mid-1960s as catheter angiography (CA), which became widely available at academic institutions [12] (fig. 1). It was soon recognized that inflammatory conditions of the CNS were associated with recurring but nonspecific patterns of angiographic abnormalities [13]. CA, along with clinical features, laboratory testing, and noninvasive imaging became increasingly relied upon to diagnose patients [14]. This trend has slowed as investigators increasingly pointed out the importance of tissue diagnosis through a brain/leptomeningeal biopsy (LMBx) prior to initiating immunosuppressive therapy [15].

Fig. 1.

Illustration of autopsy findings of inflammatory vascular changes included in the early angiographic paper by Hinck et al. [12].

Understanding the role of CA in the diagnosis of PCNSV has been hampered by the lack of a standardized approach to its use. Investigators have focused on only a few of the multitude of angiographic changes described in this condition. In this study, we selected case series of 5 or more subjects who underwent both CA and tissue diagnosis. We identified the angiographic features described as consistent with PCNSV and proposed that when all features were considered, CA served as a sensitive, if not specific screening test for PCNSV. The clinical, imaging, and laboratory context in which the results of the CA are placed increases its specificity, and determines whether additional tissue diagnosis is needed along with visualization of a more precise location for tissue acquisition.

Methods

A search of the PubMed database was performed for all cases of CNS vasculitis (CNSV) published in the English literature between 1922 and December 2014. Search terms included: vasculitis, vasculopathy, arteritis, central nervous system, brain, CNS, cerebral, arteriography, angiography, biopsy, digital subtraction, conventional, catheter, DSA, leptomeningeal, brain, and meningeal. Case series and cohort studies with ≥5 subjects were included. Additional case series and cohorts were identified through a review of article references of each study. Two independent investigators reviewed and selected articles according to the predefined selection criteria.

Each cases series or cohort study meeting the above criteria was reviewed and the following data points were collected: gender, age range, number of patients included, number of patients undergoing CA, number of patients undergoing LMBx, number of patients with CA consistent with vasculitis, number of patients with LMBx consistent with vasculitis, number of patients with CA consistent with vasculitis and nondiagnostic biopsy, number of patients with nondiagnostic CA and LMBx diagnostic of vasculitis. Additionally, a comprehensive list of angiographic descriptors consistent with vasculitis was generated, and the use of each descriptor in individual studies was quantified.

Results

A total of 25 articles meeting the search criteria were identified in which 558 unique subjects were reported (table 4) [7, 8, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35]. Fifteen of these studies included only adults (mean age 44.9 years), 5 included both adults and children, and 2 included only children (mean age 7.6 years). Three articles did not specify the age groups included. In the articles specifying gender (22/25), 54% were female.

Table 4.

Studies meeting the search criteria and included in the analysis [7, 8, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35]

| First author [Ref.] | Year | Design | Age, years | n | Angio | Angio+ | CoW | Bx | Bx+ | Biopsy location | Bx+ Angio– | Bx– Angio+ | Bx+ Angio+ |

| Calabrese 7 | 1988 | R | 3–74 | 48 | 31 | 31 | Y | 37 | 36 | cortex, LM | none | none | 8 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Koo 16 | 1988 | CR | 44–78 | 5 | 4 | 4 | Y | 3 | 3 | cortex, LM | 3 | none | 1 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Crane 14 | 1991 | CR | 23–38 | 11 | 11 | 11 | Y | 2 | 0 | temporal A | none | 11 | none |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Lie 17 | 1992 | R | 28–79 | 15 | 8 | 8 | Y | 8 | 14 | NR | 1 | 1 | 6 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Greenan 18 | 1992 | R | 3–44 | 7 | 7 | 7 | Y | 3 | 1 | RFL, LM | none | 2 | 1 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Stone 19 | 1994 | R | 32–62 | 125 | 125 | 125 | NR | 5 | 0 | NR | none | none | none |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Abu-Shakra 20 | 1994 | R | 26–53 | 16 | 16 | 16 | Y | 1 | 0 | TL, ND | none | none | none |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Duna 15 | 1995 | R | NR | 30 | 24 | 24 | Y | 15 | 4 | cortex, LM | 0 | 3 | 4 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Chu 21 | 1998 | R | 18–78 | 30 | 9 | 9 | Y | 12 | 10 | TL, cerebellum, OL, FL, PL, FP, LM | none | none | 7 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Woolfenden 22 | 1998 | R | 33–71 | 10 | 10 | 10 | Y | 3 | 0 | cortex, LM, temporal A | none | 10 | none |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Alrawi 23 | 1999 | R | NR | 61 | 22 | 22 | NR | 61 | 22 | cortex, LM | 12 | none | 4 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Gallagher [241 | 2001 | R | 5–11 | 5 | 5 | 5 | Y | 1 | 0 | temporal A | 0 | 1 | none |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Hajj-Ali 25 | 2002 | R | 10–65 | 16 | 16 | 16 | NR | 2 | 0 | NR | none | 16 | none |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Volcy 26 | 2004 | R | 16–36 | 5 | 2 | 2 | Y | 5 | 5 | cortex, LM | none | none | 2 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Kadhodayan 27 | 2004 | R | 29–88 | 38 | 38 | 38 | Y | 38 | 2 | cortex, LM | 2 | 14 | none |

|

| |||||||||||||

| MacLaren [281 | 2005 | R | 16–55 | 105 | 10 | 10 | Y | 1 | 1 | NR | none | none | none |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Salvarani [81 | 2007 | R | 17–84 | 101 | 84 | 84 | Y | 49 | 31 | brain, spinal cord | 8 | 18 | 6 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Aviv [291 | 2007 | R | 0–18 | 25 | 25 | 25 | Y | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Kuker 30 | 2008 | R | 2–76 | 27 | 6 | 6 | Y | 8 | 4 | NR | 1 | none | 1 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Berlit 31 | 2008 | R | 27–62 | 6 | 6 | 6 | Y | 6 | 6 | cortex, LM | 4 | none | 2 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Yin [321 | 2009 | R | 19–45 | 8 | 4 | 4 | Y | 4 | 4 | cortex, LM | NR | NR | none |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Kraemer 33 | 2011 | R | 11–65 | 21 | 17 | 17 | NR | 12 | 6 | cortex, LM | 2 | 5 | none |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Néel 34 | 2012 | R | 21–71 | 33 | 31 | 31 | Y | 2 | 1 | NR | none | 1 | 1 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| de Boysson 35 | 2014 | R | 18–79 | 52 | 48 | 48 | Y | 31 | 19 | ND, FL | 10 | 12 | 5 |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Geri 36 | 2014 | R | 37–54 | 32 | 12 | 12 | Y | 4 | 1 | cortex, LM | none | none | NR |

R = Retrospective study; CR = case report; NR = not reported; CoW = circle of Willis; Bx = biopsy; Angio = catheter angiogram; LM = leptomeningeal; temporal A = temporal artery; RFL = right frontal lobe; ND = nondominant; TL = temporal lobe; OL = occipital lobe; FL = frontal lobe; PL = parietal lobe; FP = frontoparietal.

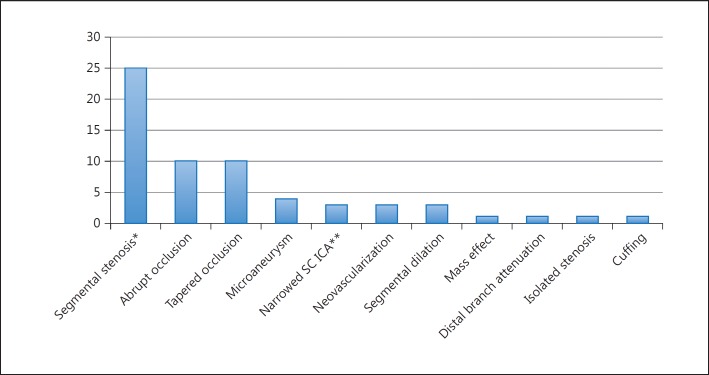

Angiograms were performed in 408 subjects (73%) of which 324 were abnormal (79.4%). Fifteen angiographic descriptors of vasculitic changes were reported in the articles reviewed. The frequency of use of each angiographic descriptor is shown in figure 2. Arterial occlusion was the most frequently utilized descriptor (20/24 articles) followed by segmental stenosis (16/24) and beading (11/24).

Fig. 2.

Frequency of use of angiographic descriptors among the 25 articles identified as meeting the search criteria. * Beading, alternating stenosis and dilation, alternating stenosis and ectasia, and a ‘sausage’ pattern were considered synonyms of segmental stenosis. ** Attenuation of distal arterial branches. SC ICA = Supraclinoid internal carotid artery.

Biopsies were performed in 17 of the identified case series and in 241 subjects; 135 subjects had biopsy results consistent with vasculitis (56%).

Discussion

Epidemiology

The overall annual incidence of systemic vasculitides (excluding giant cell arteritis) is 39 per 1,000,000 persons [36]. The incidence of systemic vasculitis involving the CNS is unclear (table 1).

The incidence of PCNSV in Olmsted County, Minn., USA, was estimated to be 2.4 per 1,000,000 person-years. Men and women are affected equally. The median age of the affected patients is 50 years and it most commonly occurs between the 4th and 6th decades of life [8]. However, there are also numerous case reports of PCNS occurring in children [30].

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiological triggers and mechanisms of vasculitis affecting the nervous system are likely different for each subtype with a final common pathway of vascular inflammation. A review of the mechanisms thought to underlie the systemic vasculitides is beyond the scope of this article [37].

The immunologic trigger(s) of PCNSV has/have not been definitively identified. However, numerous infectious etiologies including viral (especially varicella zoster virus) and mycobacterial organisms have been implicated [38, 39, 40]. In some patients, the inflammatory response may be related to the deposition of amyloid in the vessel wall [41]. Leukocytes, in particular memory T cells, concentrated in the vessel wall of PCNSV samples may indicate the presence of a cross-reacting antigenic trigger [42]. Metalloproteinase 9 seems to play an important role in vessel wall damage in animal models of vasculitis [43].

Clinical Presentation

The presentations of vasculitis involving the CNS have been described as ‘protean’ [16]. This diversity of manifestations has made clinical diagnosis and scientific investigation challenging. The three most common neurological symptoms of PCNSV in order of frequency are subacute headache, altered cognition, and focal neurological deficits [8]. Systemic manifestations, more characteristic of secondary CNSV, are numerous with organ tropism depending on the subtype in question (table 1).

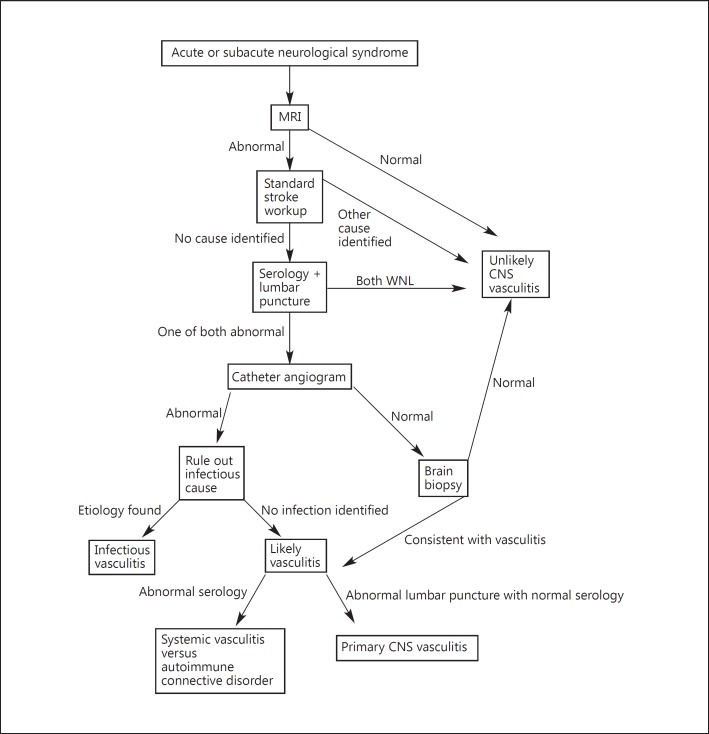

Diagnostic Algorithm

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended once a progressive or sudden CNS syndrome is suspected. MRI is highly sensitive to detect vasculitis involving the CNS, especially when combined with a suggestive CSF analysis [19]. The typical pattern includes multiple, bilateral, gray and white matter T2 hyperintense lesions. Inclusion of diffusion-weighted sequences will allow new and old lesions to be distinguished. Other findings include parenchymal and/or leptomeningeal enhancement [44] and intracranial hemorrhage [45]. The probability of diagnosing vasculitis involving the CNS after normal MRI is extremely low (fig. 3; table 5).

Fig. 3.

A flow diagram illustrating a systematic approach to the workup of possible CNSV.

Table 5.

Causes of vasculitis

| Noninfectious inflammatory | |

| Allergic granulomatosis (Churg-Strauss) | |

|

| |

| Amyloid-β-related angiitis | |

|

| |

| Behcet's disease | |

|

| |

| Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis | |

|

| |

| Giant cell (temporal) | |

|

| |

| Henoch-Schonlein purpura | |

|

| |

| Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis | |

|

| |

| Kawasaki disease | |

|

| |

| Lymphomatoid granulomatosis | |

|

| |

| Microscopic polyangiitis | |

|

| |

| Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis | |

|

| |

| Polyarteritis nodosa | |

|

| |

| Takayasu arteritis | |

|

| |

| Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger) | |

|

| |

| Vasculitis with connective tissue disease | dermatomyositis, mixed connective tissue disease, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren's syndrome, scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus |

|

| |

| Vasculitis with other autoimmune diseases | Crohn's disease |

|

| |

| Wegener's granulomatosis | |

|

| |

| Infectious | |

| Bacterial | mycobacterium tuberculosis, treponema pallidum, Borrelia burgdorferi, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Bartonella henselae |

|

| |

| Fungal | Aspergillosis, mucormycosis, coccidioidomycosis, candidiasis |

|

| |

| Paracytic | Cysticercosis |

|

| |

| Rickettsial | |

|

| |

| Viral | VZV, CMV, HIV, hepatitis C, Parvovirus B19 |

|

| |

| Neoplasm | |

| Atrial myxoma | |

|

| |

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | |

|

| |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | intravascular large B-cell lymphoma |

|

| |

| Leukemia | |

|

| |

| Small cell lung cancer | |

|

| |

| Drugs | |

| Allopurinol | |

|

| |

| Amphetamines | |

|

| |

| Bath salts | |

|

| |

| Cocaine | |

|

| |

| Ecstasy (MDMA) | |

|

| |

| Ephedrine | |

|

| |

| Heroin | |

|

| |

| Methamphetamines | |

|

| |

| Phenylpropanolamine | |

|

| |

| Other vasculopathies | |

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis | |

|

| |

| Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome | |

|

| |

| Atherosclerosis | |

|

| |

| Fibromuscular dysplasia | |

|

| |

| Moyamoya disease | |

|

| |

| Reversible vasoconstriction syndrome | benign angiopathy of the CNS, Call-Fleming syndrome, migrainous vasospasm or migraine angiitis, postpartum angiopathy |

|

| |

| Sarcoid | |

|

| |

| Sickle cell anemia | |

|

| |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | |

|

| |

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura | |

Once clinical suspicion of CNSV has been raised on clinical and imaging grounds, a detailed laboratory evaluation is essential to rule out underlying systemic inflammation including infections or rheumatic conditions. Serum markers of inflammation and antibodies associated with underlying systemic inflammatory disorders are performed (table 6). Signs of systemic inflammation are generally absent in PCNSV [30].

Table 6.

High-yield diagnostic clues

| History | Airway allergic-hypersensitivity (Churg-Strauss) | Monocular vision loss (giant cell) | Jaw claudication (giant cell) | Tobacco use (Buerger's) | Dry eyes and mouth (Sjogren's) | Use of allopurinol or ephedrine-containing products; ‘bath salts’ or ecstasy | Thunderclap HA (RVCS or SAH) |

|

| |||||||

| Physical examination | Mucus membrane ulcers and uveitis (Behcet's or syphillis) | ‘Boggy’, tender temple (giant cell) | Lymphadenopathy (Kawasaki's or Hodgkin's lymphoma) | Hand, foot, mouth erythema (Kawasaki's) | Diminished pulses/asymmetric BP in young (Takayasu's) | Rash and myalgia (dermatomyositis) | |

|

| |||||||

| ESR/CRP elevation | Giant cell | Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Kawasaki's | Polyarteritis nodosa | |||

|

| |||||||

| Blood testing | Low complement (urticarial) | HIV (lymphoid granulomatosis v.) | Hep C (lymphoid granulomatosis v. or cryoglobulinemia) | Acute renal failure (microscopic polyangiitis) | Elevated ACE levels (sarcoid v.) | Peripheral smear (sickle cell, leukemia) | Thrombocytopenia (TTP) |

|

| |||||||

| Serology | Elevated serum IgA (Henoch-Schonlein purpura) | Elevated cryoglobulins (cryoglobulinemia) | Anti-C1q Ab (urticarial) | Rheumatoid factor (RF vasculitis) | Anti-U1-RNP Ab (mixed connective tissue) | Anti-ENA (SLE) | Anti-phospholipid Ab (APL syndrome) |

|

| |||||||

| P-ANCA | Microscopic polyangiitis | Churg-Strauss | |||||

|

| |||||||

| C-ANCA | Wegener's | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Anti-nuclear Abs | Speckled (mixed connective tissue) | SSA/Ro (Sjogren's) | SSB/La (Sjogren's) | Anti-topoisomerase (scleroderma) | Anti-centromere (scleroderma) | Anti-Smith (SLE) | Anti-dsDNA (SLE) |

|

| |||||||

| Viral titers | EBV (lymphoid granulomatosis v.) | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Urine testing | Proteinuria (microscopic polyangiitis) | Hematuria (microscopic polyangiitis) | Tox screen: amphetamines, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines | ||||

|

| |||||||

| CXR | Small cell CA | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Echocardiogram | Atrial myoma | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| CT head | Convexity SAH (RVCS) | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| MRI without gadolinium | T2 hyperintense lesions almost always present in vasculitis | Microhemorrhages (amyloid angiopathy) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| MRI with gadolinium | Ring enhancing with mural nodule (cysticercosis) | ADEM pattern enhancement | |||||

|

| |||||||

| CTA/MRA | Extacranial luminalirreg. (FMD, giant cell, Takaysu's) | Intracranial vesselirreg. (1° or 2° vasculitis vs. RVCS) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Lumbar puncture | Protein elevation (1° or 2° vasculitis) | VDRL (syphilitic) | Gram stain and culture (bacterial) | Flow cytometry and cytology (lymphoma) | |||

|

| |||||||

| CSF antigen | Pneumococcus | Meningococcus | H. influenzae | Cryptococcus | |||

|

| |||||||

| CSF PCR | Viral: VZV, CMV, HIV, hepatitis C, Parvovirus B19 | Bacterial: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Treponema pallidum, Borrelia burgdorferi, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Bartonella henselae | Fungal: aspergillosis, mucormycosis, coccidioidomycosis, candidiasis | Paracytic: cysticercosis | |||

|

| |||||||

| Chest CT | Small cell lung CA | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Skin testing | Positive pathergy test (Behcet's) | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Biopsy | Renal-IgA/C3 in glomerulus (Henoch-Schölein purpura) | Lymph node (Hodgkin's) | |||||

Cerebrospinal fluid is abnormal in 80–90% of patients with PCNSV. The typical profile is mild lymphocytic pleocytosis and elevated protein level (>45 mg/dl) [8]. CSF analysis is useful to exclude infection and malignancy as a cause of neurologic deficits.

Noninvasive vascular imaging through CT angiography or magnetic resonance angiography is often utilized in the evaluation of CNSV. The resolution of these modalities limits their utility in assessing the small intracranial vessels distal to the first segments. Magnetic resonance angiography and CT angiography are less invasive than CA but not sensitive in cases of lesions associated with the posterior circulation.

Vessel wall imaging is an emerging MR-based modality and holds great promise for increasing the specificity of MRI in the diagnosis of CNSV. The technique involves high-resolution, gadolinium-enhanced, T1-weighted images of the medium and small intracranial vessels. It has successfully identified vessel wall enhancement and thickening in patients with PCNSV [29]. However, the availability of high-resolution MRI and expertise in vessel wall imaging remains limited.

Role of CA

Cerebral angiography was introduced by the Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz in 1927 [46]. The role of angiography in the diagnosis of PCNSV emerged in the mid-1960s as CA became widely available at academic institutions [12]. It was soon recognized that inflammatory conditions of the CNS were associated with patterns of angiographic abnormalities that were consistent if nonspecific. The cause of angiographic abnormalities may include: spasm, edema, cellular infiltration, proliferation of the vessel wall, compression of surrounding thickened meninges from exudate or fibrosis, weakening of a damaged vessel wall, and vasoparalysis secondary to an adjacent inflammatory process [13].

Since Calabrese and Mallek [7] proposed diagnostic criteria for PCNSV, ‘classic angiographic features of angiitis within the CNS’ have been relied upon in many centers as a cornerstone of diagnosis. However, controversy has arisen in recent years surrounding this practice. Many now suggest that the low sensitivity and specificity of angiography in several case series argues for biopsy prior to initiating treatment of PCNSV [27].

This argument is based on the assumption that biopsy is the ‘gold standard’ in the diagnosis of PCNSV. However, there are a number of cases reported of subjects in whom biopsies were negative, but were found to have PCNSV at autopsy [7, 17]. Missed diagnoses on biopsy are not surprising given the fact that involvement may be segmental and patchy [47]. In addition, ‘classic angiographic features’ may have been interpreted too narrowly by many angiographers, leading to the reduced sensitivity of CA. Our analysis shows a heavy reliance on segmental stenosis and dilation in multiple vascular territories as the angiographic finding of vasculitis. While this may indeed be the abnormality most consistently found in CNSV, there are numerous other abnormalities that are reported in the literature as being associated with true CNSV. More subtle findings such as mass effect, delayed transit time, neovascularization, early venous filling, microaneurysms, or attenuation of distal branches were infrequently cited in the literature. Duna and Calabrese [15] proposed a grading system for cerebral angiographic findings consisting of:

high probability (vascular beading or alternating areas of stenosis and ectasia in multiple cerebral vessels);

medium probability (the above findings in a single vessel), and

low probability (mass effect, isolated stenosis or occlusion).

We would like to suggest a modification of this system as follows:

high probability (vascular beading or alternating areas of stenosis and ectasia in multiple cerebral vessels);

medium probability [two or more low-frequency findings (i.e. mass effection, isolated occlusion/stenosis, delayed transit time, etc.)], and

low probability (a single low-frequency finding).

It is crucial for the angiographer to be familiar with the numerous subtle/low-frequency angiographic manifestations of CNSV in order to maximize the sensitivity of CA. Failure to do so may explain the wide variation in estimates of sensitivity in the literature.

One hypothesis posited to explain the often discordant findings on CA and biopsy in PCNSV is the existence of two variants: one affecting the ‘small vessels’ (small-vessel disease, SVD) that are beyond the resolution of CA and a second affecting the ‘medium vessels’ (MVD) angiographically visible segments of the circle of Willis [28]. MVD involves the intracranial internal carotid artery, vertebral arteries, basilar artery, proximal anterior, middle, and posterior arteries. CA, in this subgroup, shows the classic patterns described to be associated with CNSV in the literature and may have a more benign/monophasic course. SVD involves intracranial arteries of the second division branches or smaller and is not well resolved on CA. These patients display patterns of leptomeningeal or cortical enhancement on gadolinium-enhanced MRI [42] and more prominent elevations in CSF protein levels and leukocytosis. If correct, this hypothesis would explain the multiple cases of angiographic vasculitis with normal biopsy findings (MVD) and normal angiographic finding but positive biopsy results (SVD). However, further validation is required before this hypothesis is accepted.

Angiographic mimics of CNSV are numerous. The most common of these is atherosclerotic disease. Typically, atherosclerotic intracranial disease is more proximal, eccentric, and involves shorter segments than do vasculitis lesions [18]. However, this is not universally true and there are well-documented cases of atherosclerosis mimicking the ‘high probability’ anigographic pattern described above. RVCS is a second angiographic mimic of CNSV, but can be effectively distinguished using a combination of clinical features and laboratory findings (table 3). Finally, infections of the CNS can trigger a vasospastic process that mimics CNSV, and a broad array of CSF stains, cultures and immunological testing is necessarily to rule out infectious etiologies [13].

The diagnosis of childhood PCNSV relies heavily on CA as biopsies are generally avoided in the pediatric population. Small case series indicate that childhood PCNSV may affect larger/more proximal vessels of the anterior circulation and be more frequently unilateral [24, 29].

Role of Biopsy

Angiography has become the most frequent test used to diagnose PCNSV; however brain biopsy is still cited as the gold standard by many authors [31]. MRI is highly sensitive to PCNSV (nearly 100% sensitivity), and angiography can be indicative of vasculitis in the majority of cases, but the findings in these imaging studies are not specific to this disease [45, 47, 48]. Additionally, there are infectious diseases that can cause a similar clinical and radiographic picture, specifically cerebral angiitis from rickettsial, spirochetal, viral, and bacterial sources. If these diagnoses are missed, the initiation of immunosuppressive treatment is potentially hazardous [47, 48]. Therefore, biopsy may play an important role in appropriately selected patients.

The target for biopsy is usually based on MRI findings, as an abnormality on MRI increases the likelihood of obtaining diagnostic tissue [8]. Two primary techniques have been described: stereotactic and open. Stereotactic biopsies are performed with neuronavigation used to guide a large bore biopsy needle through a burr hole into the target identified on MRI. Multiple core biopsies are taken and sent for histopathology. This technique is particularly useful for deeply seated lesions or in eloquent areas. Open biopsies are performed by using a small craniotomy to expose more superficial structures. A 1-cm3 specimen is resected en bloc and should include overlying dura, a cortical vessel, and both gray and white matter from the targeted gyrus [32, 49]. Neuronavigation can also be utilized to accurately locate the target for biopsy. If no target is identified on imaging, a right frontal or temporal tip biopsy has been advocated, as these areas are low risk for causing deficits [47, 49]. In a study by Pulhorn et al. [50], biopsies were obtained for suspicion of vasculitis as well as other neurologic conditions. They found that tissue was diagnostic or suggestive of a diagnosis in 46% of open biopsy and 64% of stereotactic biopsy. This difference appeared to be related to the higher likelihood of having a targeted abnormality on MRI in the stereotactic group. Therefore, the chosen approach should be based on the MRI findings to produce the highest likelihood of diagnostic yield.

Brain biopsy for CNSV has been shown to be diagnostic in only 30–60% of cases in the available series [8, 32, 34, 48, 50]. Biopsy is felt to be useful both in the diagnosis of PCNSV as well as to rule out other diagnoses, and is complementary to other diagnostic modalities including angiography to guide clinical decision-making. In one study of the 43 premortem biopsies which were pathologically confirmed, 11 were false negatives [51], leading to a calculated 74.4% sensitivity. False negatives were present in 1/4 of the procedures. It is speculated that false negatives occur due to segmental involvement of vessels [48].

Morbidity of brain biopsy has been reported to be between 0.03 and 2% [32, 48]. The potential risk of surgery must be balanced with the risk of proceeding with empiric immunosuppressive therapy. In a paper by Chu et al. [21], aggressive immunosuppression had a higher morbidity than either angiography or brain biopsy.

An additional consideration is the next step, should brain biopsy return negative. This is a controversial question, and several studies have advocated a conservative approach with close clinical follow-up without initiation of immunosuppression [52]. Other authors feel that if suspicion of PCNSV remained high despite negative biopsy, proceeding with immunosuppression is warranted, especially once infection has been excluded to an acceptable degree [32, 48].

Histology

Three main histological patterns are seen to affect patients with PCNSV:

granulomatous: the most commonly seen pattern (∼60%); vasculocentric mononuclear inflammation and well-formed granulomas with multinucleated cells;

lymphocytic: second most common (∼30%); lymphocytic inflammation with occasional plasma cells and vessel destruction; more commonly seen in children and angiographynegative PCNSV, and

necrotizing: least common (∼10–15%); transmural fibrinoid necrosis similar to PAN; associated with intracranial hemorrhage [23, 53].

Medical Therapy

The treatment of vasculitis with or without CNS involvement relies heavily on glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressive medications [54]. A disease-specific description of treatment strategies in systemic, noninfectious, inflammatory conditions associated with CNSV is beyond the scope of this article.

The early report of PCNSV was diagnosed at autopsy and the disease was believed to be generally fatal [7]. However, in 1983, a paradigm shift occurred when Cupps et al. [9] described several therapeutic successes that relied on cyclophosphamide and glucocorticoids. Since that time, initial treatment has continued to include glucocorticoids alone, or in conjunction with cyclophosphamide. Other agents that have been described include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, TNF-α blockers, and rituximab. Over 80% of patients respond favorably to the initial treatment regimen. Initial monotherapy is associated with a higher rate of relapse than dual therapy with a second immunosuppressive agent [55].

Conclusion

Diagnosis of PCNSV from imaging modalities has evolved at a seemingly gradual pace. Most of this can be attributed to nonspecific clinical presentation, variation in sensitivity of imaging results and reliance on brain biopsy for diagnosis. Once careful history, laboratory findings, and CSF analysis are obtained, one major question is how important the role of CA is in the diagnosis of CNSV. We proposed a modification in the grading system of angiography that will maximize its sensitivity. Through greater emphasis on ordinary and low-frequency changes, the suggested modifications will allow cerebral angiography to become prominent in the diagnostic algorithm of CNSV. Understanding how to combine these results with biopsy findings of small and medium vessels will result in even more effective interpretations, and ultimately allow for halting damage from disease progression.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no disclosures relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Kussmaul A, Maier R. Ueber eine bisher nicht beschriebene eigentümliche Arterienerkrankung (Periarteritis nodosa), die mit Morbus Brightii und rapid fortschreitender allgemeiner Muskellähmung einhergeht. Dtsch Arch Klin Med. 1866;1:484–518. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longcope WT. Periarteritis nodosa, with report of a case with autopsy. Bull Ayer Clin Lab. 1908;5:1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Churg J, Strauss L. Allergic granulomatosis, allergic angiitis, and periarteritis nodosa. Am J Pathol. 1951;27:277–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harbitz F. Unknown forms of arteritis, with special reference to their relation to syphilitic arteritis and periarteritis nodosa. Am J Med Sci. 1922;163:250–271. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman W, Wolf A. Non-infectious granulomatous angiitis involving the central nervous system. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1952;56:114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cravioto H, Feigin I. Noninfectious granulomatous angiitis with a predilection for the nervous system. Neurology. 1959;9:599–609. doi: 10.1212/wnl.9.9.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabrese LH, Mallek JA. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Report of 8 new cases, review of the literature, and proposal for diagnostic criteria. Medicine (Baltimore) 1988;67:20–39. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salvarani C, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Ann Neurol. 2007;2:442–451. doi: 10.1002/ana.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cupps TR, Moore PM, Fauci AS. Isolated angiitis of the central nervous system. Prospective diagnostic and therapeutic experience. Am J Med. 1983;74:97–105. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Call GK, et al. Reversible cerebral segmental vasoconstriction. Stroke. 1988;19:1159–1170. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calabrese LH, et al. Narrative review: reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:34–44. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-1-200701020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinck VC, Carter CC, Rippey JG. Giant cell (cranial) arteritis: a case with angiographic abnormalities. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1964;92:769–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferris EJ, Levine HL. Cerebral arteritis: classification. Radiology. 1973;109:327–341. doi: 10.1148/109.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crane R, Kerr LD, Spiera H. Clinical analysis of isolated angiitis of the central nervous system. A report of 11 cases. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:2290–2294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duna GF, Calabrese LH. Limitations of invasive modalities in the diagnosis of primary angiitis of the central nervous system. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:662–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koo EH, Massey EW. Granulomatous angiitis of the central nervous system: protean manifestations and response to treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51:1126–1133. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.9.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lie JT. Primary (granulomatous) angiitis of the central nervous system: a clinicopathologic analysis of 15 new cases and a review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:164–171. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenan TJ, Grossman RI, Goldberg HI. Cerebral vasculitis: MR imaging and angiographic correlation. Radiology. 1992;182:65–72. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.1.1727311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stone JH, et al. Sensitivities of noninvasive tests for central nervous system vasculitis: a comparison of lumbar puncture, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1277–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abu-Shakra M, Khraishi M, Grosman H, Lewtas J, Cividino A, Keystone EC. Primary angiitis of the CNS diagnosed by angiography. Q J Med. 1994;87:351–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu CT, et al. Diagnosis of intracranial vasculitis: a multi-disciplinary approach. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:30–38. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199801000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolfenden AR, Tong DC, Marks MP, Ali AO, Albers GW. Angiographically defined primary angiitis of the CNS: is it really benign? Neurology. 1998;51:183–188. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alrawi A, et al. Brain biopsy in primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Neurology. 1999;53:858–860. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallagher KT, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system in children: 5 cases. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:616–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hajj-Ali RA, Furlan A, Abou-Chebel A, Calabrese LH. Benign angiopathy of the central nervous system: cohort of 16 patients with clinical course and long-term follow-up. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:662–669. doi: 10.1002/art.10797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volcy M, Toro ME, Uribe CS, Toro G. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: report of five biopsyconfirmed cases from Colombia. J Neurol Sci. 2004;227:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kadkhodayan Y, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system at conventional angiography. Radiology. 2004;233:878–882. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333031621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacLaren K, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: emerging variants. QJM. 2005;98:643–654. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aviv RI, et al. Angiography of primary central nervous system angiitis of childhood: conventional angiography versus magnetic resonance angiography at presentation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:9–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuker W, et al. Vessel wall contrast enhancement: a diagnostic sign of cerebral vasculitis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;26:23–29. doi: 10.1159/000135649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berlit P, Kraemer M. Cerebral vasculitis in adults: what are the steps in order to establish the diagnosis? Red flags and pitfalls. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:419–424. doi: 10.1111/cei.12221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin Z, Li X, Fang Y, Luo B, Zhang A. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: report of eight cases from southern China. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:63–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraemer M, Berlit P. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: clinical experiences with 21 new European cases. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:463–472. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Néel A, Auffray-Calvier E, Guillon B, Fontenoy AM, Loussouarn D, Pagnoux C, Hamidou MA. Challenging the diagnosis of primary angiitis of the central nervous system: a single-center retrospective study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1026–1034. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Boysson H, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: description of the first fifty-two adults enrolled in the French cohort of patients with primary vasculitis of the central nervous system. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:1315–1326. doi: 10.1002/art.38340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geri G, Saadoun D, Guillevin R, Crozier S, Lubetzki C, Mokhtari K, Amoura Z, Wechsler B, Le Boutin D, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Samson Y, Cacoub P. Central nervous system angiitis: a series of 31 patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:105–110. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watts RA, Carruthers DM, Scott DG. Epidemiology of systemic vasculitis: changing incidence or definition? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1995;25:28–34. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(95)80015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams HP., Jr Cerebral vasculitis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:475–494. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-7020-4086-3.00031-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagel MA, et al. The varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: clinical, CSF, imaging, and virologic features. Neurology. 2008;70:853–860. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304747.38502.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas L, Davidson M, McCluskey RT. Studies of PPLO infection. I. The production of cerebral polyarteritis by Mycoplasma gallisepticum in turkeys; the neurotoxic property of the Mycoplasma. J Exp Med. 1966;123:897–912. doi: 10.1084/jem.123.5.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arthur G, Margolis G. Mycoplasma-like structures in granulomatous angiitis of the central nervous system. Case reports with light and electron microscopic studies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1977;101:382–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salvarani C, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: comparison of patients with and without cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1671–1677. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwase T, et al. Involvement of CD45RO+ T lymphocyte infiltration in a patient with primary angiitis of the central nervous system restricted to small vessels. Eur Neurol. 2001;45:184–185. doi: 10.1159/000052120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams PL, et al. Levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 within cerebrospinal fluid in a rabbit model of coccidioidal meningitis and vasculitis. J Infect Dis. 2002;86:1692–1695. doi: 10.1086/345365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burger PC, Burch JG, Vogel FS. Granulomatous angiitis. An unusual etiology of stroke. Stroke. 1977;8:29–35. doi: 10.1161/01.str.8.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edgell RC, et al. Interventional neurology: a reborn subspecialty. J Neuroimaging. 2012;22:319–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2010.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Hunder GG. Adult primary central nervous system vasculitis. Lancet. 2012;380:767–777. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Birnbaum J, Hellmann DB. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:704–709. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parisi JE, Moore PM. The role of biopsy in vasculitis of the central nervous system. Semin Neurol. 1994;14:341–348. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1041093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pulhorn H, et al. Impact of brain biopsy on the management of patients with nonneoplastic undiagnosed neurological disorders. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:833–837. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000318168.97966.17. discussion 837–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alreshaid AA, Powers WJ. Prognosis of patients with suspected primary CNS angiitis and negative brain biopsy. Neurology. 2003;61:831–833. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000081047.22043.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller DV, et al. Biopsy findings in primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:35–43. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318181e097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Minagar A, et al. Neurologic presentations of systemic vasculitides. Neurol Clin. 2010;28:171–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salvarani C, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in primary central nervous system vasculitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hughes JT, Brownell B. Granulomatous giant-celled angiitis of the central nervous system. Neurology. 1966;16:293–298. doi: 10.1212/wnl.16.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kolodny EH, Rebeiz JJ, Caviness VS, Jr, Richardson EP., Jr Granulomatous angiitis of the central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 1968;19:510–524. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1968.00480050080008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Snyder BD, McClelland RR. Isolated benign cerebral vasculitis. Arch Neurol. 1978;35:612–614. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1978.00500330060012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valavanis A, Friede R, Schubiger O, Hayek J. Cerebral granulomatous angiitis simulating brain tumor. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1979;3:536–538. doi: 10.1097/00004728-197908000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]