Abstract

About one-third of patients with suspected gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) do not respond symptomatically to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Many of these patients do not suffer from GERD, but may have underlying functional heartburn or atypical chest pain. Other causes of failure to respond to PPIs include inadequate acid suppression, non-acid reflux, oesophageal hypersensitivity, oesophageal dysmotility and psychological comorbidities. Functional oesophageal tests can exclude cardiac and structural causes, as well as help to confi rm or exclude GERD. The use of PPIs should only be continued in the presence of acid reflux or oesophageal hypersensitivity for acid reflux-related events that is proven on functional oesophageal tests.

Keywords: acid reflux, GERD, non-acid reflux, pH-impedance, reflux hypersensitivity

Ms Olivia has been troubled by symptoms that resemble gastro-oesophageal reflux disease since her 40th birthday several years ago. She was prescribed proton pump inhibitors by several different doctors and has been taking them regularly with no improvement. She underwent gastroscopy about five years ago that reported normal results. In recent months, she underwent a cardiac evaluation that was also normal. She did not experience dysphagia, weight loss or vomiting.

WHAT IS GASTRO-OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE?

The Montreal definition proposed that gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition that develops when the reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications.(1) Heartburn and regurgitation are typical symptoms of GERD. The Montreal consensus also includes a number of extra-oesophageal symptoms potentially attributed to GERD.(1) It further defines ‘troublesome’ symptoms as an impairment in health-related quality of life for ≥ 2 days/week for mild symptoms or ≥ 1 day/week for moderate symptoms. The latest Rome IV classification proposes a more restrictive definition of GERD, limiting it to patients who have endoscopic features of reflux oesophagitis and/or elevated oesophageal acid exposure on functional oesophageal tests.(2)

HOW COMMON IS THIS IN MY PRACTICE?

Although GERD is a predominantly Western disease, with a prevalence of 10%–20% in North America and Western Europe,(3) changing dietary patterns and a rise in obesity have resulted in the increasing prevalence of GERD in Asia.(4) The prevalence of symptom-based GERD in Southeast Asia has been rising(5) and was estimated to be 6.3%–18.3% from 2005–2010.(6)

Current guidelines recommend the use of acid-suppressive therapy with proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy as the first-line approach to GERD treatment.(7-9) PPIs suppress gastric acid secretion and have a profound effect on oesophageal mucosal healing.(10) Despite the high efficacy of PPIs, up to 30% of patients continue to experience GERD-like symptoms even when adequately dosed.(7,8) Patients who do not respond to PPIs or have any alarm symptoms (e.g. dysphagia, odynophagia, weight loss, vomiting and/or abdominal pain) require further evaluation. Gastroscopy is useful to exclude sinister conditions, especially in patients who have additional risk factors such as smoking, older age and a family history of upper gastrointestinal cancers.

After exclusion of any underlying serious aetiology, it is not uncommon for patients to continue to experience GERD-like symptoms. With the widespread use of PPIs, the failure to resolve GERD symptoms is now one of the most common presentations of GERD in gastroenterology clinics as well as the general practice setting. Patients who have atypical symptoms, such as unexplained chronic cough and throat symptoms, and do not respond well to PPIs are also commonly encountered. In such situations, the diagnosis of GERD remains doubtful(11,12) and ambulatory oesophageal reflux monitoring is useful to determine if the symptoms are indeed due to GERD.(12)

GERD is a costly disease, especially if PPI treatment failure results in patients seeking a second opinion, or receiving a higher dose or different course of PPIs. Compared to patients with erosive oesophagitis, patients with non-erosive reflux disease (i.e. the endoscopic features of reflux esophagitis are absent) have a 20% reduction in therapeutic gain from PPIs.(13) Apart from the high treatment costs, it has been observed that up to 55% of patients with persistent GERD symptoms report an impaired quality of life.(14)

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

History

There is no gold standard for the diagnosis of GERD. In our daily practice, we often rely on the subjective reporting of a constellation of symptoms and attribute these to GERD. For patients who fail to respond to PPIs, a variety of causes are possible, both GERD-related and non-GERD-related.

A good history can clarify the nature of the patient’s symptoms and which symptoms respond or persist despite PPI therapy. Heartburn is characterised by a painful retrosternal burning sensation lasting for a short duration. Regurgitation is described as a backflow of gastric contents into the chest or mouth. Establishing compliance to PPIs, including the timing of medications and proper dosages, is important in the initial evaluation. PPIs are typically started at a standard dose on a once-daily basis. If the patients do not respond, the physician can increase the dose to twice daily for a defined period of time (approximately eight weeks) and monitor the response to establish if the patients should continue taking PPIs for presumptive GERD or undergo further diagnostic tests. In clinical trials, PPIs are more efficacious for relieving symptoms of heartburn compared to regurgitation.(15,16)

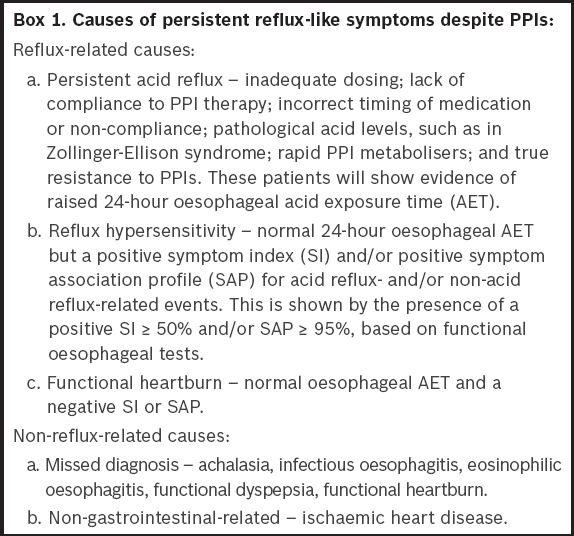

It is also important to establish if a non-GERD-related aetiology (Box 1) is the cause of persistent symptoms. GERD is often overdiagnosed; atypical symptoms that are common and even less responsive to PPIs include chest pain in the absence of any abnormalities on cardiac evaluation; unexplained chronic cough that has been evaluated by a respiratory physician; or persistent throat symptoms despite a normal ear, nose and throat evaluation.(17) Lastly, underlying anxiety and psychological comorbidities have to be excluded, as these conditions are frequently reported in patients with PPI-refractory symptoms who have underlying psychological comorbidities. Patients with high anxiety levels were reported to have persistent reflux-like symptoms.(18)

Box 1.

Causes of persistent reflux-like symptoms despite PPIs

Functional gastro-oesophageal disorders have a negative impact on treatment outcomes.(19) Based on the latest Rome IV criteria,(2) functional heartburn and reflux hypersensitivity are part of the functional oesophageal disorders spectrum. These are characterised as disorders presenting with typical oesophageal symptoms that are not explained by a structural lesion, oesophageal motility disorder or underlying GERD. A diagnosis of functional oesophageal disorder has an arbitrary requirement of symptom onset at least six months before diagnosis and symptoms of at least three months’ duration.(2) In addition, patients with functional heartburn may have symptom overlap with functional dyspepsia(20) or irritable bowel syndrome.(21)

Questionnaires

Various questionnaires have been employed to diagnose GERD, but as these are neither sensitive nor specific for reflux,(22) their use does not increase diagnostic accuracy.(23) The GerdQ questionnaire(24) comprises positive predictor questions about heartburn and regurgitation, and negative predictor questions about epigastric pain and nausea. Its sensitivity (65%) and specificity (71%) for GERD diagnosis were reported to be comparable to the clinical judgment of gastroenterologists.(25) However, most of these questionnaires lack sensitivity and specificity, and cannot reliably distinguish GERD from functional dyspepsia. Language barriers, complexities in symptom description and cross-cultural differences are the main difficulties preventing the widespread use of GERD questionnaires in our local population.(26)

Response to proton pump inhibitors

Response to PPIs remains one of the most specific predictors of GERD and is useful in the primary care setting. The PPI test consists of measuring the symptomatic response to a 1–2-week course of a high-dose PPI in patients with GERD symptoms. The rationale for a high-dose PPI (typically a double dose) is the need to suppress gastric acid secretion and heal erosive oesophagitis.(27)

There is a lack of consensus on the definition of a PPI non-responder.(28) The dose of PPIs and duration of treatment required to fulfil the criteria is not well defined, varying from single to double dose, and ranging from 8–12 weeks, respectively. Sifrim and Zerbib(29) defined refractory GERD as heartburn and/or regurgitation symptoms occurring at least three times per week despite a stable double dose of PPI, during a treatment period of at least 12 weeks. In a prospective study of 544 patients with typical GERD symptoms, a 75% symptom response to a double dose of PPIs of one week’s duration showed a sensitivity of 96.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 94%–98%) and specificity of 34.6% (95% CI 25%–43%) for a diagnosis of GERD.(30)

Lifestyle changes

Dietary modifications and lifestyle measures are useful for GERD patients. Weight loss in patients who are overweight or have recent weight gain has been proven to improve GERD symptoms, as well as elevation of the head of the bed.(31) Patients should also avoid a supine position immediately after meals and having meals up to two hours before bedtime. Dietary triggers for reflux include caffeine, chocolate, carbonated beverages and foods with high fat content.

WHAT INVESTIGATIONS ARE PERFORMED IN A SPECIALIST SETTING?

Gastroscopy

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends endoscopy for patients with GERD symptoms that persist despite appropriate medical therapy.(32) Gastroscopy has poor sensitivity(26,33) but good specificity (90%–95%)(33) for the diagnosis of GERD in the presence of the endoscopic features of reflux oesophagitis, peptic strictures, erosions, ulcers and Barrett’s oesophagus. However, the majority of patients with refractory reflux symptoms will have normal endoscopy. Nevertheless, gastroscopy remains an important screening tool to exclude an underlying organic lesion of the upper gastrointestinal tract and allow for oesophageal biopsies in conditions such as pill-induced oesophagitis, skin diseases with oesophageal involvement, peptic ulceration of the oesophagus and eosinophilic oesophagitis.

Functional oesophageal tests

In patients who remain symptomatic despite PPIs, functional oesophageal tests provide a useful objective measure of oesophageal function after exclusion of any structural lesion or cardiac cause. Oesophageal manometry is an important diagnostic tool to exclude achalasia(34,35) as well as other major motility disorders, including oesophageal spasm, aperistalsis and hypercontractile oesophagus.(36) Ambulatory 24- or 48-hour oesophageal pH studies or 24-hour combined pH-impedance studies are well-described diagnostic modalities used by gastroenterologists to confirm or exclude GERD as a cause of persistent symptoms. This would avoid the unnecessary use of PPIs when there is no objective evidence of GERD.

Oesophageal pH monitoring

Ambulatory reflux monitoring plays an important role in the diagnosis of GERD.(37) Oesophageal pH monitoring can be performed using either the conventional nasopharyngeal pH catheter monitoring system, for a period of 24 hours, or the wireless 48-hour pH monitoring device (i.e. Bravo® capsule). Compared to the nasopharyngeal catheter system, the wireless capsule is cosmetically more acceptable to most patients, as it is attached to the lower oesophageal mucosa and allows for a longer duration of monitoring of up to 48 hours. Based on normal values that were previously published for the 24-hour nasopharyngeal catheter system(38) and wireless Bravo capsule,(39) we can objectively quantify oesophageal acid exposure (usually expressed as the percentage of time during which pH < 4). GERD is diagnosed in the presence of an elevated oeosphageal acid exposure time. In addition, ambulatory reflux monitoring allows physicians to establish the temporal association between the patient’s symptom episodes and acid reflux events. A symptom episode is considered to be reflux-related if symptom onset occurs within two minutes of a reflux event. The importance of symptom association in a patient who continues to have persistent reflux-like symptoms is that it allows us to distinguish reflux hypersensitivity (positive symptom association) from functional heartburn (negative symptom correlation).(2)

Combined pH-impedance monitoring

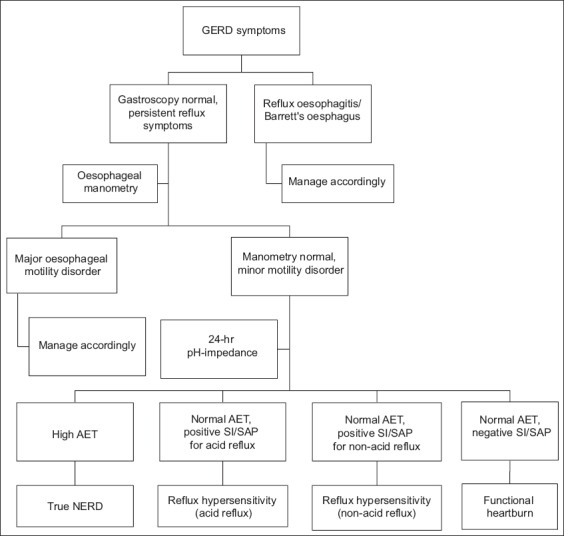

In recent times, there has been an increasing awareness of non-acid reflux as a cause of persistent symptoms. Unlike the conventional 24-hour nasopharyngeal pH monitoring device, which measures only events related to acid reflux, the combined pH-impedance monitoring device can measure both events related to acid reflux (pH < 4) and non-acid reflux (pH ≥ 4). In addition, it permits further characterisation of the nature of the refluxate (i.e. air, reflux or mixed air-liquid reflux),(40) and the number of acid and non-acid reflux events. Apart from the objective measurement of reflux events, pH-impedance studies also allow the patient’s symptoms to be directly correlated with both acid and non-acid reflux events. Studies have shown that non-acid reflux accounts for persistent reflux-like symptoms in patients who respond poorly to PPIs.(41,42) Based on the results of functional diagnostic tests, the causes of PPI-refractory GERD can be classified as reflux-related or non-reflux-related (Fig. 1 & Box 1).(43)

Fig. 1.

Flow chart shows stratification of patients evaluated for persistent gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms. AET: acid exposure time; NERD: non-erosive reflux disease; SAP: symptom association probability; SI: symptom index

For PPI non-responders who have an elevated number of reflux episodes on 24-hour pH-impedance studies, the use of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation (tLESR) inhibitors can be considered. Baclofen, a gamma-aminobutyric acid agonist that reduces the frequency of tLESRs and number of reflux events, can be beneficial for patients who continue to have persistent reflux symptoms despite PPIs. However, the central side effects of baclofen, especially dizziness and drowsiness, have restricted its widespread use. Once the diagnosis of a functional oesophageal disorder has been made, appropriate treatment should be instituted, while PPIs should be stopped. The use of visceral pain modulators may be beneficial in patients who have functional heartburn or oesophageal hypersensitivity.(44-46) However, psychological comorbidities can also affect oesophageal perception, resulting in reduced pain thresholds.(45) The use of pain modulators, including tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, was reported to be beneficial.(46)

Ms Olivia underwent gastroscopy, which returned normal results, and oesophageal manometry to exclude any underlying oesophageal motility disorders. Her 24-hour combined pH-impedance study showed a normal oesophageal acid exposure time and negative symptom association profile (i.e. symptoms of heartburn did not correspond to any reflux event during ambulatory reflux monitoring). Further history revealed that she was having difficulty coping with her job while taking care of her three school-going children, as her husband was often overseas. She was referred to a psychologist and underwent cognitive behavioural therapy for underlying anxiety and stress management. Her husband was supportive and changed his job to spend more time at home. At her last clinic visit, Ms Olivia showed much improvement and had stopped her acid suppressants.

CONCLUSION

Despite major advances in our understanding of GERD, management remains a challenge. Due to their established efficacy and safety, PPI treatment is often used as a therapeutic trial to diagnose GERD in the absence of alarm symptoms such as bleeding, weight loss, anaemia or dysphagia.(47) A single dose of PPI provides adequate symptom relief in most patients; however, some may require dose escalation to twice a day. Patients unresponsive to PPI therapy are often labelled as having refractory GERD.

Failure to respond to a complete course of PPIs should alert the clinician to a non-GERD cause. The continued use of PPIs without objective evidence of GERD often leads to high costs. Once a structural cause has been excluded following gastroscopy, discussion with the patient on the role of further functional evaluation, including manometry and ambulatory studies, is useful to obtain a definitive diagnosis. This would avoid unnecessary costs from the overuse of PPIs and identify patients with functional heartburn. Treatment options for functional heartburn include a trial of pain modulators or psychological treatment such as cognitive behavioural therapy and muscle relaxation techniques.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

GERD is a common condition, but overdiagnosis (especially in patients with atypical manifestations) leads to the unnecessary prescription of PPIs and high costs for patients.

Primary care physicians play a crucial role in assessing the patient and should take into account the symptom profile as well as any underlying psychological comorbidities.

The presence of any alarm symptoms (e.g. dysphagia, odynophagia, weight loss, abdominal pain and/or vomiting) warrants early referral to a gastroenterologist for further evaluation.

Start PPIs at a once-daily standard dose and monitor the patient’s response. Patients who continue to remain symptomatic should be referred for further evaluation. The most common first-line investigation is gastroscopy. In patients without structural lesions, functional oesophageal tests that gastroenterologists may perform include oesophageal manometry and 24-hour ambulatory pH-impedance studies. These tests measure oesophageal acid exposure and reflux numbers, and assess the temporal association between the patient’s symptom episodes and reflux events.

In the absence of high oesophageal acid exposure or a positive symptom association, repeated prescriptions for PPIs and escalation of acid-suppressive therapy are ineffective and lead to unnecessary costs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease:a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. quiz 1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aziz Q, Fass R, Gyawali G, et al. Functional esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012. pii:S0016-5085(16)00178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease:a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vakil N. Disease definition, clinical manifestations, epidemiology and natural history of GERD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:759–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goh KL. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia:a historical perspective and present challenges. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(Suppl 1):2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung HK. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia:a systematic review. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:14–27. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigterman KE, van Pinxteren B, Bonis PA, Lau J, Numans ME. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD002095. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002095.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sifrim D, Zerbib F. Diagnosis and management of patients with reflux symptoms refractory to proton pump inhibitors. Gut. 2012;61:1340–54. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zerbib F, Sifrim D, Tutuian R, Attwood S, Lundell L. Modern medical and surgical management of difficult-to-treat GORD. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:21–31. doi: 10.1177/2050640612473964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekel R, Morse C, Fass R. The role of proton pump inhibitors in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Drugs. 2004;64:277–95. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, et al. American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1383–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308–28. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.444. quiz 329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dean BB, Gano AD, Jr, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:656–64. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta N, Inadomi JM, Sharma P. Perception about gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and its impact on daily life in the general population:results from a large population based AGA survey. Gastroenterol. 2012;142(Suppl 1):S411. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahrilas PJ, Howden CW, Hughes N. Response of regurgitation to proton pump inhibitor therapy in clinical trials of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1419–25. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.146. quiz 1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahrilas PJ, Jonsson A, Denison H, Wernersson B, Hughes N, Howden CW. Regurgitation is less responsive to acid suppression than heartburn in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:612–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickman R, Boaz M, Aizic S, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease who failed proton pump inhibitor therapy versus those who fully responded. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:387–94. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becher A, El-Serag H. Systematic review:the association between symptomatic response to proton pump inhibitors and health-related quality of life in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:618–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu JC, Lai LH, Chow DK, et al. Concomitant irritable bowel syndrome is associated with failure of step-down on-demand proton pump inhibitor treatment in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:155–60.e31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savarino E, Pohl D, Zentilin P, et al. Functional heartburn has more in common with functional dyspepsia than with non-erosive reflux disease. Gut. 2009;58:1185–91. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.175810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung HK, Halder S, McNally M, et al. Overlap of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and irritable bowel syndrome:prevalence and risk factors in the general population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:453–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ates F, Francis DO, Vaezi MF. Refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease:advances and treatment. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8:657–67. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2014.910454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aanen MC, Numans ME, Weusten BL, Smout AJ. Diagnostic value of the Reflux Disease Questionnaire in general practice. Digestion. 2006;74:162–8. doi: 10.1159/000100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dent J, Vakil N, Jones R, et al. Accuracy of the diagnosis of GORD by questionnaire, physicians and a trial of proton pump inhibitor treatment:the Diamond Study. Gut. 2010;59:714–21. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.200063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones R, Junghard O, Dent J, et al. Development of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1030–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quigley EM, Lacy BE. Overlap of functional dyspepsia and GERD--diagnostic and treatment implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:175–186. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiba N, De Gara CJ, Wilkinson JM, Hunt RH. Speed of healing and symptom relief in grade II to IV gastroesophageal reflux disease:a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1798–1810. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richter JE, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF, et al. Esophageal Diagnostic Working Group. Utilization of wireless pH monitoring technologies:a summary of the proceedings from the esophageal diagnostic working group. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:755–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sifrim D, Zerbib F. Diagnosis and management of patients with reflux symptoms refractory to proton pump inhibitors. Gut. 2012;61:1340–54. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pace F, Pace M. The proton pump inhibitor test and the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;4:423–7. doi: 10.1586/egh.10.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaltenbach T, Crockett S, Gerson LB. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux? An evidence-based approach. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:965–71. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Standards of Practice Committee. Lichtenstein DR, Cash BD, et al. Role of endoscopy in the management of GERD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:219–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venables TL, Newland RD, Patel AC, et al. Omeprazole 10 milligrams once daily, omeprazole 20 milligrams once daily, or ranitidine 150 milligrams twice daily, evaluated as initial therapy for the relief of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in general practice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:965–73. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lacy BE, Paquette L, Robertson DJ, Kelley ML, Jr, Weiss JE. The clinical utility of esophageal manometry. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:809–15. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818ddbd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ponce J, Ortiz V, Maroto N, et al. High prevalence of heartburn and low acid sensitivity in patients with idiopathic achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:773–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:160–74. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirano I, Richter JE Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. ACG practice guidelines:esophageal reflux testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:668–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson LF, DeMeester TR. Development of the 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring composite scoring system. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8(Suppl 1):52–8. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198606001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pandolfino JE, Richter JE, Ours T, et al. Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring using a wireless system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:740–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bredenoord AJ. Impedance-pH monitoring:new standard for measuring gastro-oesophageal reflux. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:434–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy:a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut. 2006;55:1398–402. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.087668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boeckxstaens GE, Smout A. Systematic review:role of acid, weakly acidic and weakly alkaline reflux in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:334–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dellon ES, Shaheen NJ. Persistent reflux symptoms in the proton pump inhibitor era:the changing face of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:7–13.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maradey-Romero C, Fass R. Antidepressants for functional esophageal disorders:evidence- or eminence-based medicine? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:260–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fass R, Tougas G. Functional heartburn:the stimulus, the pain, and the brain. Gut. 2002;51:885–92. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dickman R, Maradey-Romero C, Fass R. The role of pain modulators in esophageal disorders - no pain no gain. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:603–10. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vaezi MF. “Refractory GERD”:acid, nonacid, or not GERD? Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:989–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.