Abstract

Objective

Recent studies implicate cardiolipin oxidation in several age-related diseases. Atp8b1 encoding Type 4 P-type ATPases is a cardiolipin transporter. Mutation in Atp8b1 gene or inflammation of the lungs impairs the capacity of Atp8b1 to clear cardiolipin from lung fluid. However, the link between Atp8b1 mutation and age-related gene alteration is unknown. Therefore, we investigated how Atp8b1 mutation alters age-related genes.

Methods

We performed Affymetrix gene profiling of lungs isolated from young (7-9 wks, n=6) and aged (14 months, 14 M, n=6) C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant mice. In addition, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) was performed. Differentially expressed genes were validated by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR).

Results

Global transcriptome analysis revealed 532 differentially expressed genes in Atp8b1 lungs, 157 differentially expressed genes in C57BL/6 lungs, and 37 overlapping genes. IPA of age-related genes in Atp8b1 lungs showed enrichment of Xenobiotic metabolism and Nrf2-mediated signaling pathways. The increase in Adamts2 and Mmp13 transcripts in aged Atp8b1 lungs was validated by qRT-PCR. Similarly, the decrease in Col1a1 and increase in Cxcr6 transcripts was confirmed in both Atp8b1 mutant and C57BL/6 lungs.

Conclusion

Based on transcriptome profiling, our study indicates that Atp8b1 mutant mice may be susceptible to age-related lung diseases.

Keywords: gene profiling, lungs, aging, transcriptome, Atp8b1 mutant

INTRODUCTION

Aging is associated with an overall decline in lung function, changes in lung physiology, and an increased susceptibility to diseases [1]. Lung injury and inflammation are associated with the aging process and are also observed during acute lung injury (ALI) [2]. As aging has been linked to the development of several lung diseases, understanding the underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms of aging is a pre-requisite for developing novel therapeutics for age-related lung diseases including, but not limited to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), lung fibrosis, and lung cancer [2]. The process of normal physiological aging leads to enlarged alveolar spaces and loss of lung elasticity [3]. A combination of both intrinsic factors, such as age-dependent gene changes, and extrinsic factors, such as epigenetics and environmental stress, increase susceptibility to lung diseases [4]. Some of the age-associated features include increased oxidative stress, commonly in the form of reactive oxygen species (ROS, accumulation), alteration in the extracellular matrix (ECM), decreased production of anti-aging molecules, reduced antioxidant response, autophagy, and defective mitochondria [1, 4-6].

Mitochondria are the cellular power supply, providing energy required for cell survival. At the same time, mitochondria are involved in sensing danger signals and frequently cause inflammation by regulating the innate immune system [7]. Mitochondrial ROS have been implicated in the aging process and oxidative stress-induced pathology [8]. During normal physiological conditions, low levels of mitochondria-produced ROS serve as a redox sensor which regulates intracellular sig-naling and leads to cellular homeostasis [9], but excessive ROS can cause irreversible damage and result in mitochondrial dysfunction and eventually apoptosis [10].

Mitochondrial membrane phospholipids play an important role in the aging process as a result of modulating oxidative stress and molecular integrity [11]. Cardiolipin is a phospholipid that is localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane and is involved in regulating several mitochondrial bioenergetic processes, mitochondrial stability, and dynamics [11]. In lungs, the type II alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) secrete cardiolipin, a minor constituent of the alveolar surfactant, into airways [12]. In many pathological conditions, there is alteration in the structure and content of cardiolipin leading to mitochondrial dysfunction [13]. An example of this occurs during lung inflammation and injury, where an increased amount of cardiolipin is seen in the airways. This suggests that under normal conditions, the cardiolipin availability in extracellular fluid or airways is tightly regulated. Recent studies suggest that cardiolipin oxidation or age-related depletion leads to mitochondrial bioenergetic alteration, mitochondrial dysfunction, and eventually cell death [11, 13, 14].

Atp8b1 is a cardiolipin transporter and is critical for maintaining optimal cardiolipin levels in airways and extracellular fluids [15]. During inflammation, or when Atp8b1 is defective, its capacity to remove cardiolipin from lung fluid is impaired [15]. Mutations in the Atp8b1 gene are associated with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 1 (PFIC1, or Byler's disease) [16]. These individuals are susceptible to pneumonia and respiratory symptoms [15]. Atp8b1 mutant mice and humans with pneumonia have elevated levels of cardiolipin in lung fluid, which disrupts the function of the surfactant. Furthermore, cardiolipin dysregulation has been associated with aging [11]. However, the link between the Atp8b1 mutation and age-related genes has not yet been studied. Therefore, the main aim of this study was to investigate how Atp8b1 mutation alters age-related genes.

Global gene profiling in lungs is critical to developing a better understanding of the molecular and cellular events that are associated with aging of lungs. Transcriptome analysis in various mouse tissues has explored age-associated changes in gene expression and effects of caloric restriction [17, 18]. Few studies have determined the age-related changes in lung transcript-tome using mouse models [9, 10]. Therefore, in the present study, we used C57BL/6 mice and Atp8b1 mutant mice (on C57BL/6 background) to study and compare age-dependent changes in gene expression.

The Affymetrix microarray analysis of lungs isolated from C57BL/7 mice at 7-9 wks and 14 M showed 157 differentially expressed genes associated with aging. Interestingly, 532 differentially expressed genes were linked to aging in Atp8b1 mutant mice We identified 37 overlapping genes in two data sets, 85 unique genes in C57BL/7 lungs and 350 unique genes in Atp8b1 mutant lungs. We validated several genes by qRT-PCR in Atp8b1 mutant lungs including Col1a1, Mmp13, Adamts2 and CxCr6. Similarly the transcripts Col1a1 and CxCr6 were also validated in C57BL/6 by qRT-PCR. Further, our gene profiling study indicates that distinct gene pathways, including xenobiotic metabolism and Nrf2 signaling pathway, are altered in Atp8b1 mutant mice relative to C57BL/6 mice in an age-dependent manner. Taken together, these results suggest that Atp8b1 mutant mice may be susceptible to age-related lung fibrosis, a phenotype associated with gene mutation and environmental trigger(s).

RESULTS

Age-related phenotype in Atp8b1 mutant mice

Lungs are the primary organs where gas exchange takes place. On account of a high oxygen environment, the post-mitotic cells in lungs are susceptible to oxidative stress-related injury in an age-dependent manner [3]. This phenotype is shared among other tissues with high oxygen consumption rates including skeletal muscle, as well as heart and brain tissues [17, 18]. Atp8b1 encodes a membrane-bound transporter Atp8b1 (ATPase, aminophospholipid transporter, class I, type 8B, member 1) that regulates AEC function. Atp8b1 mutant mice carrying the mutation in the membrane-bound transporter showed decreased lung function and had an increased susceptibility to bacterial-induced pneumonia and epithelial cell apoptosis [15]. Therefore, we investigated the transcriptome of Atp8b1 mutant lungs to study age-related changes in gene transcripts.

Gene profiling studies revealed age-related genes in Atp8b1 mutant and C57BL/6 lungs

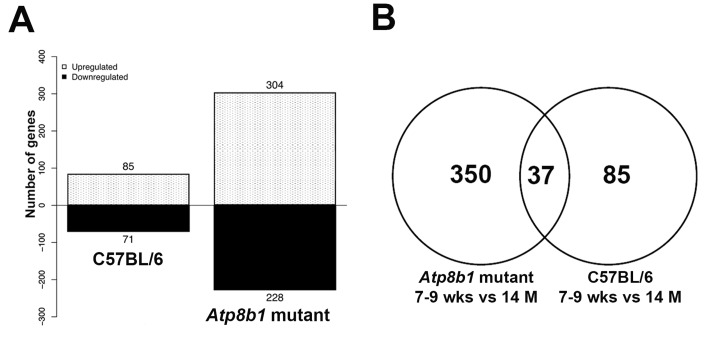

First, we performed microarray analysis in C57BL/6 lungs at 7-9 wks (N=6, adult) and 14 M (N=6, old) using Affymetrix Mouse 430v2.0 microarray. Gene profiling revealed 157 genes that were differentially expressed in an age-dependent manner. Of these, 85 genes were up-regulated and 71 genes were down-regulated in C57BL/6 lungs (Figure 1A). Some of the transcripts that were either increased or decreased with aging in C57BL/6 lungs included Akap13, Calml3, Cdc73, Fbox15, Jak1, Midn, Mkx, Wif1, Wdpcp, and Zbtb16 (Table 1).

Figure 1. Differentially expressed genes in C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant lungs.

(A) Differentially expressed genes in the young (7-9 wk) (N=6) vs. aged (14 M) (N=6) C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant lungs from a total of 34,000 genes that were analyzed by Affymetrix microarray, respectively. p < 0.05. (B) Venn diagram depicting overlapping and unique genes in aged C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant lungs. Comparison of the differentially expressed genes (7-9 wks vs 14 M) in C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant lungs revealed 37 overlapping genes between the two datasets, 350 unique genes in Atp8b1 mutant lungs and 85 unique genes in C57BL/6 lungs.

Table 1. Differentially expressed genes associated with aging in C57BL/6 lungs (q<0.1, mean-value difference between two groups >1.0).

| Transcripts that are downregulated in C57BL/6 mice with aging | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affymetrix Probe Set ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Fold Change | FDR (q value) | ||

| 1438239_at | Midn | midnolin | −3.737 | 0.0666 | ||

| 1439163_at | Zbtb16 | zinc finger and BTB domain containing 16 | −2 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1458423_at | Luc7l2 | LUC-like 2 | −1.937 | 0.0666 | ||

| 1439122_at | Ddx6 | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 6 | −1.819 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1427638_at | Zbtb16 | zinc finger and BTB domain containing 16 | −1.44 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1452899_at | Rian | RNA imprinted and accumulated in nucleus | −1.405 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1444228_s_at | Herc2 | hect (homologous to the E6-AP (UBE3A) carboxyl terminus) domain and RCC1 (CHC1)-like domain (RLD) 2 | −1.365 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1459619_at | Epb4.1l2 | erythrocyte protein band 4.1-like 2 | −1.365 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1449188_at | Midn | midnolin | −1.334 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1433804_at | Jak1 | Janus kinase 1 | −1.242 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1448352_at | Luzp1 | Leucine zipper protein | −1.228 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1437422_at | Sema5a | semaphorin 5A | −1.237 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1443640_at | Zfp882 | zinc finger protein 882 | −1.203 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1443923_at | Akap13 | A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 13 | −1.249 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1447787_x_at | Gjc1 | gap junction protein, gamma 1 | −1.179 | 0.0512 | ||

| Transcripts that are upregulated in C57BL/6 mice with aging | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affymetrix Probe Set ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Fold Change | FDR (q value) | ||

| 1425078_x_at | C130026I21Rik | RIKEN cDNA C130026I21 gene | 2.945 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1437492_at | Mkx | mohawk homeobox | 1.868 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1422873_at | Prg2 | proteoglycan 2, bone marrow | 1.845 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1435660_at | LOC664787 | Sp110 nuclear body protein-like | 1.676 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1422812_at | Cxcr6 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 6 | 1.673 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1418608_at | Calml3 | calmodulin-like 3 | 1.601 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1459030_at | Bbox1 | butyrobetaine (gamma), 2-oxoglutarate dioxygenase 1 (gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase) | 1.55 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1430567_at | Spink5 | serine peptidase inhibitor, Kazal type 5 | 1.48 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1425832_a_at | Cxcr6 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 6 | 1.442 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1457642_at | Skida1 | SKI/DACH domain containing 1 | 1.428 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1426280_at | Wdpcp | WD repeat containing planar cell polarity effector | 1.414 | 0.0666 | ||

| 1419528_at | Sult2a2 | sulfotransferase family 2A, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)-preferring, member 2 | 1.408 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1451840_at | Kcnip4 | Kv channel interacting protein 4 | 1.399 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1427238_at | Fbxo15 | F-box protein 15 | 1.348 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1453145_at | Pisd-ps3 | phosphatidylserine decarboxylase, pseudogene 3 | 1.329 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1418871_a_at | Phgr1 | proline/histidine/glycine-rich 1 | 1.345 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1455953_x_at | Pstk | phosphoseryl-tRNA kinase | 1.299 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1418480_at | Ppbp | pro-platelet basic protein | 1.273 | 0.0903 | ||

| 1439103_at | Cdc73 | cell division cycle 73, Paf1/RNA polymerase II complex component | 1.269 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1444040_at | Lair1 | leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptor 1 | 1.265 | 0.0512 | ||

| 1425425_a_at | Wif1 | Wnt inhibitory factor 1 | 1.26 | 0.0666 | ||

Similarly, we evaluated age-related molecular events in Atp8b1 mutant lungs by transcriptome analysis of lungs at 7-9 (N=6) and 14 M (N=6) using Affymetrix Mouse 430v2.0 microarrays. Of the 532 genes that were differentially expressed in Atp8b1 mutant lungs, there were 304 genes that were upregulated and 228 genes that were downregulated in an age-dependent manner (Figure 1A). The top differentially expressed genes (q<0.1, false discovery rate corrected Mann-Whitney U test p-value and median difference > 1.0), regardless of direction, are listed in (Table 2). Interestingly, the majority of gene transcripts were changed at least two-folds in either direction.

Table 2. Differentially expressed genes associated with aging in Atp8b1 mutant lungs (q<0.1, mean-value difference between two groups >1.0).

| Transcripts that are upregulated in Atp8b1 mutant mice with aging | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affymetrix Probe Set ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Fold Change | FDR | ||

| 1418652_at | Cxcl9 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 | 3.181 | 0.031 | ||

| 1419762_at | Ubd | ubiquitin D | 3.161 | 0.031 | ||

| 1416957_at | Pou2af1 | POU domain, class 2, associating factor 1 | 2.361 | 0.031 | ||

| 1438148_at | Cxcl3 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 3 | 2.361 | 0.031 | ||

| 1418282_x_at | Serpina1b | serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 1B | 2.359 | 0.031 | ||

| 1447792_x_at | Gpr174 | G protein-coupled receptor 174 | 2.304 | 0.0546 | ||

| 1450912_at | Ms4a1 | membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 1 | 2.236 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1423226_at | Ms4a1 | membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 1 | 2.028 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1417851_at | Cxcl13 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 13 | 2.006 | 0.031 | ||

| 1424374_at | Gimap4 | GTPase, IMAP family member 4 | 1.932 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1418480_at | Ppbp | pro-platelet basic protein | 1.916 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1417256_at | Mmp13 | matrix metallopeptidase 13 | 1.914 | 0.031 | ||

| 1425832_a_at | Cxcr6 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 6 | 1.893 | 0.031 | ||

| 1427221_at | Slc6a20a | solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter), member 20A | 1.868 | 0.031 | ||

| 1422978_at | Cybb | cytochrome b-245, beta polypeptide | 1.855 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1422029_at | Ccl20 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20 | 1.851 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1422837_at | Scel | sciellin | 1.764 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1425086_a_at | Slamf6 | SLAM family member 6 | 1.751 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1422812_at | Cxcr6 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 6 | 1.742 | 0.031 | ||

| 1436576_at | Fam26f | family with sequence similarity 26, member F | 1.733 | 0.031 | ||

| 1454157_a_at | Pla2g2d | phospholipase A2, group IID | 1.694 | 0.031 | ||

| 1425289_a_at | Cr2 | complement receptor 2 | 1.666 | 0.031 | ||

| 1439141_at | Gpr18 | G protein-coupled receptor 18 | 1.637 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1418776_at | Gbp8 | guanylate-binding protein 8 | 1.634 | 0.031 | ||

| 1451513_x_at | Serpina1b | serine (or cysteine) preptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 1B | 1.631 | 0.031 | ||

| 1448898_at | Ccl9 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 | 1.612 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1451563_at | Emr4 | EGF-like module containing, mucin-like, hormone receptor-like sequence 4 | 1.595 | 0.0947 | ||

| 1436649_at | Ikzf3 | IKAROS family zinc finger 3 | 1.592 | 0.031 | ||

| 1449254_at | Spp1 | secreted phosphoprotein 1 | 1.59 | 0.031 | ||

| 1425084_at | Gimap7 | GTPase, IMAP family member 7 | 1.58 | 0.031 | ||

| 1419560_at | Lipc | lipase, hepatic | 1.557 | 0.031 | ||

| 1444487_at | Lrat | lecithin-retinol acyltransferase (phosphatidylcholine-retinol-O-acyltransferase) | 1.521 | 0.0546 | ||

| 1418826_at | Ms4a6b | membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 6B | 1.49 | 0.031 | ||

| 1416318_at | Serpinb1a | serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade B, member 1a | 1.454 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1421098_at | Stap1 | signal transducing adaptor family member 1 | 1.453 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1448961_at | Plscr2 | phospholipid scramblase 2 | 1.444 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1454159_a_at | Igfbp2 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 | 1.444 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1424375_s_at | Gimap4 | GTPase, IMAP family member 4 | 1.413 | 0.031 | ||

| 1436941_at | Nxpe3 | neurexophilin and PC-esterase domain family, member 3 | 1.41 | 0.0546 | ||

| 1418930_at | Cxcl10 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | 1.405 | 0.031 | ||

| 1449393_at | Sh2d1a | SH2 domain protein 1A | 1.39 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1419728_at | Cxcl5 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 | 1.385 | 0.0947 | ||

| 1417620_at | Rac2 | RAS-related C3 botulinum substrate 2 | 1.383 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1422122_at | Fcer2a | Fc receptor, IgE, low affinity II, alpha polypeptide | 1.382 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1424923_at | Serpina3g | serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 3G | 1.379 | 0.031 | ||

| 1419598_at | Ms4a6d | membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 6D | 1.373 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1423467_at | Ms4a4b | membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 4B | 1.361 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1449373_at | Dnajc3 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily C, member 3 | 1.354 | 0.0947 | ||

| 1436779_at | Cybb | cytochrome b-245, beta polypeptide | 1.346 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1436778_at | Cybb | cytochrome b-245, beta polypeptide | 1.345 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1460273_a_at | Naip2 | NLR family, apoptosis inhibitory protein 2 | 1.248 | 0.031 | ||

| 1449175_at | Gpr65 | G-protein coupled receptor 65 | 1.247 | 0.031 | ||

| 1450632_at | Rhoa | ras homolog gene family, member A | 1.24 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1417292_at | Ifi47 | interferon gamma inducible protein 47 | 1.231 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1421168_at | Abcg3 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family G (WHITE), member 3 | 1.228 | 0.031 | ||

| 1420442_at | Cacna1s | calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L type, alpha 1S subunit | 1.219 | 0.0546 | ||

| 1423182_at | Tnfrsf13b | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 13b | 1.212 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1439103_at | Cdc73 | cell division cycle 73, Paf1/RNA polymerase II complex component | 1.203 | 0.031 | ||

| Transcripts that are downregulated in Atp8b1 mutant mice with aging | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affymetrix Probe Set ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Fold Change | FDR | ||

| 1416306_at | Clca3 | chloride channel calcium activated 3 | −3.201 | 0.0947 | ||

| 1439122_at | Ddx6 | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 6 | −2.153 | 0.031 | ||

| 1456379_x_at | Dner | delta/notch-like EGF-related receptor | −2.066 | 0.031 | ||

| 1455494_at | Col1a1 | collagen, type I, alpha 1 | −1.924 | 0.031 | ||

| 1449015_at | Retnla | resistin like alpha | −1.893 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1435990_at | Adamts2 | a disintegrin-like and metallopeptidase (reprolysin type) with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 2 | −1.829 | 0.031 | ||

| 1433757_a_at | Nisch | nischarin | −1.825 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1447853_x_at | Kif13a | kinesin family member 13A | −1.811 | 0.031 | ||

| 1428936_at | Atp2b1 | ATPase, Ca++ transporting, plasma membrane 1 | −1.792 | 0.031 | ||

| 1423065_at | Dnmt3a | DNA methyltransferase 3A | −1.714 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1424598_at | Ddx6 | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 6 | −1.648 | 0.031 | ||

| 1420402_at | Atp2b2 | ATPase, Ca++ transporting, plasma membrane 2 | −1.544 | 0.031 | ||

| 1456102_a_at | Cul5 | cullin 5 | −1.536 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1456489_at | Pcf11 | cleavage and polyadenylation factor subunit homolog (S. cerevisiae) | −1.535 | 0.031 | ||

| 1438069_a_at | Rbm5 | RNA binding motif protein 5 | −1.509 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1460069_at | Smc6 | structural maintenance of chromosomes 6 | −1.494 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1436746_at | Wnk1 | WNK lysine deficient protein kinase 1 | −1.478 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1444547_at | Ankrd40 | ankyrin repeat domain 40 | −1.477 | 0.031 | ||

| 1423669_at | Col1a1 | collagen, type I, alpha 1 | −1.476 | 0.031 | ||

| 1423110_at | Col1a2 | collagen, type I, alpha 2 | −1.446 | 0.031 | ||

| 1415994_at | Cyp2e1 | cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily e, polypeptide 1 | −1.443 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1438726_at | Mical2 | microtubule associated monooxygenase, calponin and LIM domain containing 2 | −1.421 | 0.0546 | ||

| 1427884_at | Col3a1 | collagen, type III, alpha 1 | −1.416 | 0.031 | ||

| 1442878_at | Prdx6 | peroxiredoxin 6 | −1.411 | 0.031 | ||

| 1427768_s_at | Myl3 | myosin, light polypeptide 3 | −1.4 | 0.0721 | ||

| 1458439_a_at | Dzip3 | DAZ interacting protein 3, zinc finger | −1.323 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1426287_at | Atxn7 | ataxin 7 | −1.319 | 0.031 | ||

| 1452899_at | Rian | RNA imprinted and accumulated in nucleus | −1.317 | 0.0947 | ||

| 1437422_at | Sema5a | sema domain, seven thrombospondin repeats (type 1 and type 1-like), transmembrane domain (TM) and short cytoplasmic domain, (semaphorin) 5A | −1.316 | 0.031 | ||

| 1452378_at | Malat1 | metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (non-coding RNA) | −1.313 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1459804_at | Crebbp | CREB binding protein | −1.248 | 0.031 | ||

| 1433758_at | Nisch | nischarin | −1.241 | 0.031 | ||

| 1438403_s_at | Malat1 /// Ramp2 | metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (non-coding RNA) /// receptor (calcitonin) activity modifying protein 2 | −1.241 | 0.0947 | ||

| 1438083_at | Hhip | Hedgehog-interacting protein | −1.232 | 0.031 | ||

| 1457193_at | Kmt2c | lysine (K)-specific methyltransferase 2C | −1.223 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1427883_a_at | Col3a1 | collagen, type III, alpha 1 | −1.213 | 0.031 | ||

| 1447863_s_at | Nr4a2 | nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 | −1.21 | 0.0399 | ||

| 1452360_a_at | Kdm5a | lysine (K)-specific demethylase 5A | −1.199 | 0.031 | ||

| 1455277_at | Hhip | Hedgehog-interacting protein | −1.196 | 0.031 | ||

| 1437933_at | Hhip | Hedgehog-interacting protein | −1.167 | 0.031 | ||

| 1418562_at | Sf3b1 | splicing factor 3b, subunit 1 | −1.117 | 0.031 | ||

Next, we compared the gene profiling dataset from Atp8b1 mutant and C57BL/6 mice to determine the variance in gene transcripts between normal aging and aging with the gene mutation. We found 37 genes that overlapped between the two datasets, 350 genes unique to the Atp8b1 mutant, and 85 unique to C57BL/6 datasets (Figure 1B). Some of the transcripts that overlapped between C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant lungs were found to decrease with aging. These included Akap13, Atrx, Col1a1, Col3a1, Ddx6, Luzp1, Rian, Sema5a, and Sfb31, whereas transcripts such as Cxcr6 and Slc6A20 increased with aging (Table S1). Notably, transcripts Col1a1 and Col3a1 encoding collagen were expected to decrease with age based on previous literature [19].

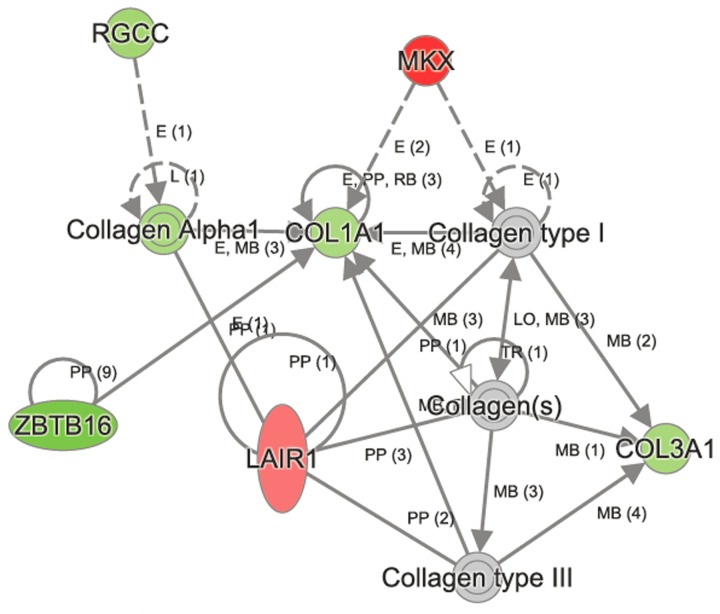

IPA identifies key gene networks in aged C57BL/6 lungs

To identify the gene networks and biological pathways that are perturbed in normal aging, we examined the microarray data from C57BL/6 lungs by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). The top canonical pathways (q<0.05) that were altered significantly in C57BL/6 lungs in age-dependent manner were vitamin C transport, intrinsic prothrombin activating pathway, hematopoiesis, from pluripotent stem cells, L-carnitine biosynthesis and ascorbate recycling (Table 3). Other canonical pathways that changed significantly in C57BL/6 were RhoA, PI3K/Akt, Oncostatin M, EGF, PDGF, Jak/Stat, iNOS, and Wnt/ β-catenin signaling pathways (Table S2). The upstream regulators of these canonical pathways included CMA1, MKL1, MKL2, NR4A2, and miR-296. One of the networks affected in C57BL/6 aging process was “cellular assembly, organization, function, and maintenance,” and includes 38 molecules (Figure 2). Some of the key molecules in this network are Akap13 (−1.249), Col1a1 (−1.042), Col3a1 (−1.071), Gjcl (−1.179), Jak1 (−1.249), Lair (1.265), Mkx (1.868), Rgcc (−1.153), and Zbtb16 (−2.0).

Table 3. Canonical pathways identified in aged C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant lungs.

| Name | Molecules | -log(p-value) |

| Top Canonical Pathways in C57BL/6 Mice | ||

| Vitamin-C Transport | GSTO2,SLC23A1 | 2.48E00 |

| Intrinsic Prothrombin Activation Pathway | COL3A1,COL1A1 | 1.91E00 |

| Hematopoiesis from Pluripotent Stem Cells | IGHM,IGHA1 | 1.91E00 |

| L-carnitine Biosynthesis | BBOX1 | 1.73E00 |

| Ascorbate Recycling (Cytosolic) | GSTO2 | 1.73E00 |

| Top Canonical Pathways in Atp8b1 Mice | ||

| Name | Molecules | -log(p-value) |

| OX40 Signaling Pathway | HLA-A,CD3G,HLA-DQA1,HLA-DQB1,CD3D,HLA-DMB,HLA-DOB,B2M,NFKBIE | 6.25E00 |

| Altered T Cell and B Cell Signaling in Rheumatoid Arthritis | SLAMF1,TNFRSF17,CD28,CXCL13,HLA-DQA1,TNFRSF13B,HLA-DQB1,CD79B, | 6.06E00 |

| HLA-DMB,HLA-DOB,SPP1 | ||

| Communication between Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells | TNFRSF17,CD28,HLA-A,CD8A,CCL5,CXCL10,TNFRSF13B,Ccl9,B2M,IGHA1 | 6.06E00 |

| Antigen Presentation Pathway | HLA-A,CD74,HLA-DQA1,HLA-DMB,HLA-DOB,B2M,PSMB8 | |

| Agranulocyte Adhesion and Diapedesis | CCXL9,CCL8,CCL5,CXCL10,MMP12,CCL20, MMP13,Glycam1,Ppbp,CXCL6,CCL19, CXCL13, CCL9, CXCL3,MYL3 |

5.98E00 |

Figure 2. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) identified perturbation of cellular assembly, organization, function, and maintenance in aged network to be perturbed in aged C57BL/6 lungs.

Some of the key molecules in this network are shown in the figure. The genes Col1a, Col3a1, Zbtb16 and Rgcc were downregulated, whereas Mkx and Lair were upregulated in aged C57BL/6 lungs.

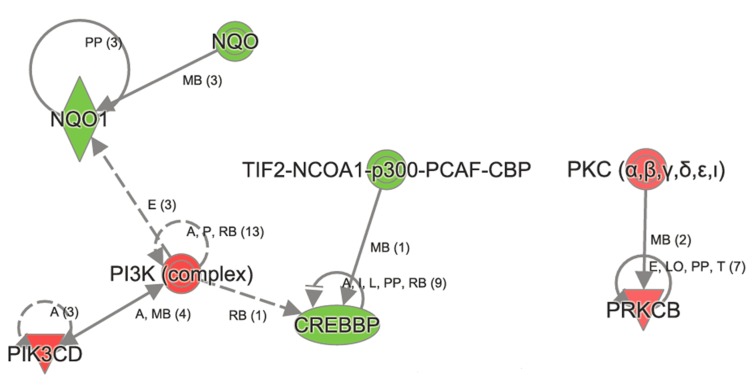

Figure 3. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis revealed genes in Xenobiotic metabolism to be affected in aged Atp8b1 mutant mice.

One of the most important transcript in Xenobiotic metabolism namely NQO1 was decreased in aged Atp8b1 mutant lungs. Members that were decreased in Xenobiotic metabolism included CREBBP and p300. The transcript encoding members in PI3K complex (PIKCD) and PKC α,β (PRKCB) were increased in aged Atp8b1 mutant lungs.

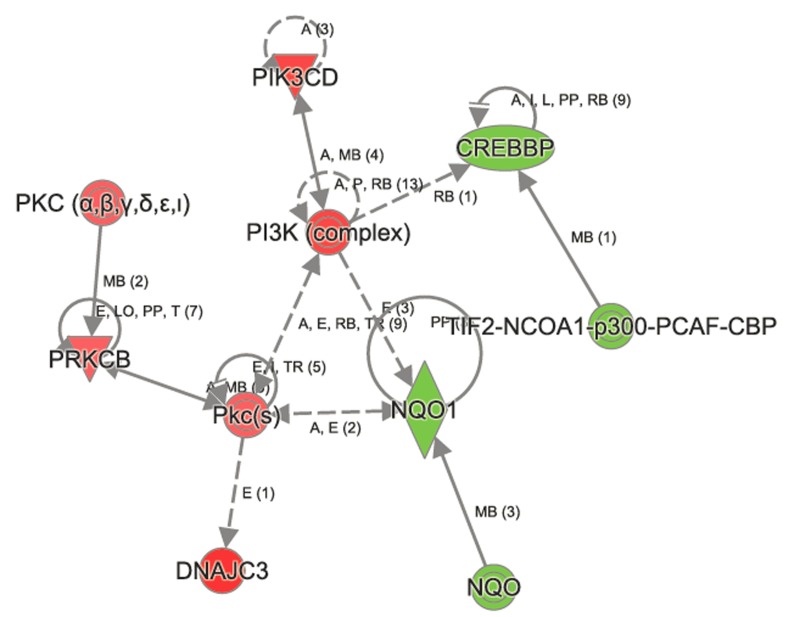

Figure 4. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis shows perturbation in Nrf2 signaling in aged Atp8b1 mutant mice.

The transcripts encoding NQO1, CREBBP, p300 were decreased in aged Atp8b1 mutant mice. Members in PI3K complex (PIK3D), PKC α,β (PRKCB, PKc(s) and DNAJC3 were increased in aged Atp8b1 mutant lung.

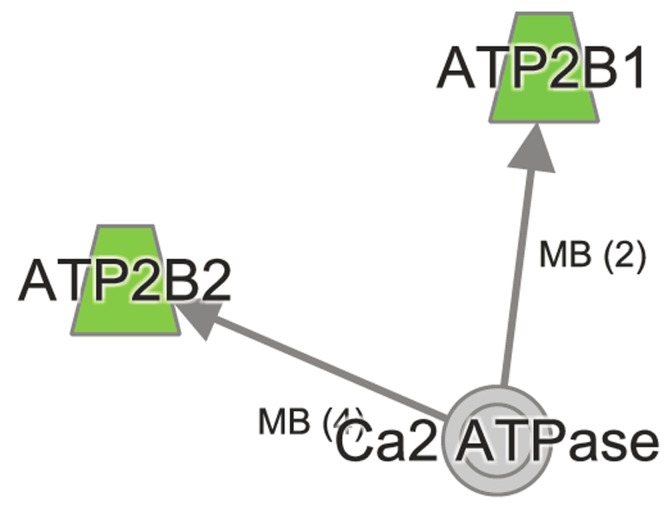

Figure 5. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis reveals dys-regulated Calcium signaling in aged Atp8b1 mutant mice.

The transcripts Atp2b1 and Atp2b2 encoding ATP2B1 and ATP2B2 that play an important role in calcium signaling were decreased in Atp8b1 mutant lung in age-dependent manner.

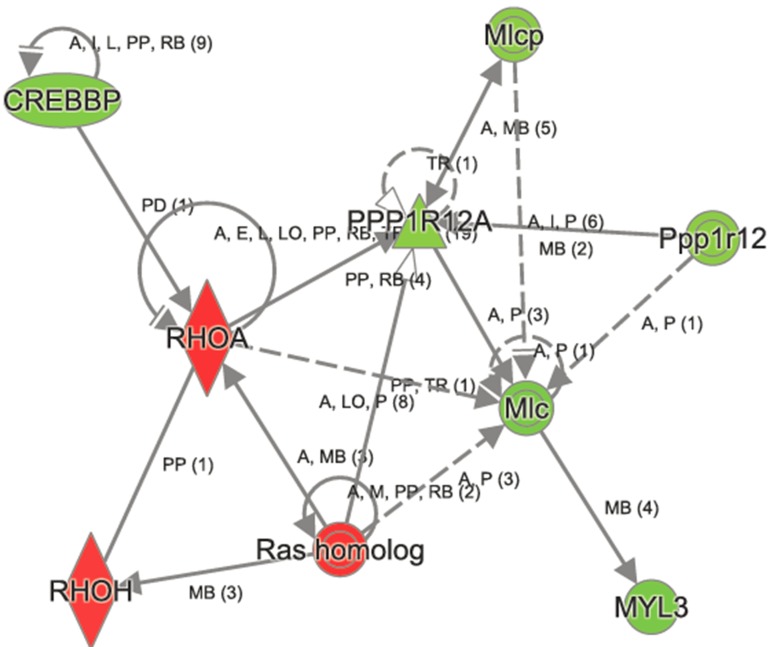

In contrast, the top canonical pathways significantly changed in Atp8b1 mutant as a result of aging are OX40 signaling, altered T cell and B cell signaling in rheumatoid arthritis, communication between innate and adaptive immune cells, the antigen presentation pathway, agranulocyte adhesion, and diapedesis (Table 3). Other canonical pathways that were significantly altered in Atp8b1 mutant mice attributed to aging were: calcium, RhoA and Rac signaling, and the xenobiotic metabolism (Table S3). The important molecules in xenobiotic metabolism and Nrf2 signaling are Nqo1 (−1.252), Crebbp (−1.248), and Pik3cd (1.219). The signaling molecules in RhoGD1 pathway are RhoA (1.241) and Rhoh (1.174) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of RhoGD1 signaling in aged Atp8b1 mutant mice.

The transcript encoding key molecules in this pathway, namely, RHOA, RHOH and Ras homologs were increased, whereas CREBBP, MYL3, Mlcp, and Ppp1r12 were decreased in aged Atp8b1 mutant mice. Symbols and Color Keys. In the Figures (2-6), upregulated genes are depicted in red and downregulated genes in green. The solid lines depict direct interaction and the dashed lines depict indirect interaction between genes. The arrow represents interaction between genes. The symbols represent the following. A= Activation, B= Binding, E= Expression, I= Inhibition, PP = Protein-Protein binding, P = Phosphorylation/Dephosphorylation, RB= regulation of binding, MB = Group/Complex membership.

Interestingly, the metalloproteinase family members Mmp12 and Mmp13 were upregulated in Atp8b1 mutant mice relative to C57BL/6 mice in an age-dependent manner. Further, many of genes linked to collagen production in lungs such as Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, and Col5a1 were downregulated with age in Atp8b1 mutant mice. Adamts2 encoding a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin Type 1 Motif, 2 was also downregulated in Atp8b1 mutant mice in age-dependent manner. In contrast, Serpina 1b encoding alpha-1 anti-trypsin was upregulated with age in Atp8b1 mutant mice suggesting its role in protecting lung tissue against neutrophil elastase. Interestingly, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase quinone 1 (NQO1) transcript, a Nrf2 target gene was significantly decreased in aged Atp8b1 mutant lungs. Another anti-oxidant gene, Prdx6 encoding peroxiredoxin 6, involved in reducing phospholipid hydroperoxide, was also similarly decreased in Atp8b1 mutant lungs.

Quantitative Real-time PCR analysis for differentially expressed transcripts in C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant mice

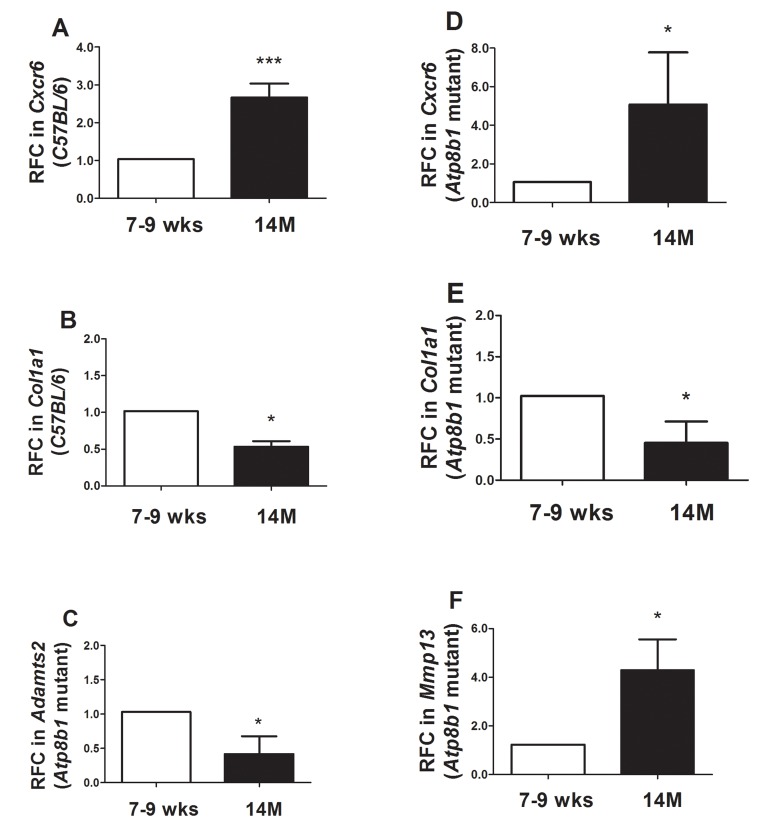

Some transcripts that were decreased or increased in Atp8b1 mutant lungs during aging were independently validated using qRT-PCR analysis. Cxcr6 encoding chemokine receptor 6 that was significantly increased in C57BL/6 during aging was validated (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR analysis confirmed several transcripts in Atp8b1 mutant and C57BL/6 lungs at 7-9 wks vs. 14 M.

(A) In C57BL/6 mice, CxCr6 transcript increased significantly at 14M relative to 7-9 wks.*** p < 0.001 relative to 7-9 wks time point. (B) In C57BL/6 mice, Col1a1 transcript significantly decreased at 14M compared to 7-9 wks. * p < 0.05 relative to 7-9 wks time point. (C) In Atp8b1 mutant, Adamts2 was significantly decreased at 14M when compared to 7-9 wks. * p < 0.05 relative to 7-9 wks time point. (D) CxCr6 transcript was significantly increased in 14M Atp8b1 mutant lungs versus 7-9 wks Atp8b1 mutant lungs. * p < 0.05 relative to 7-9 wks time point. (E) Col1a1 transcript levels decreased significantly at 14M relative to 7-9 wks in Atp8b1 mutant lungs. * p < 0.05 relative to 7-9 wks time point. (F) Mmp13 was significantly increased in aged Atp8b1 mutant lungs versus young adult lungs (7-9 wks). * p < 0.05 relative to 7-9 wks time point. For the qRT-PCR, N=6 mice were tested per group. Student's T test was used to calculate statistical significance between the two groups.

Col1a1 which was decreased in C57BL/6 mice in aging was also validated by qRT-PCR (Figure 7B). Adamts2 encoding an ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombo-spondin Type 1 Motif, 2 was also validated by qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 7C). Similar to C57BL/6 mice, an increase in CxCr6 transcript encoding chemokine receptor 6 in Atp8b1 mutant mice was validated (Figure 7D). Likewise, Col1a1 was significantly decreased at 14 M relative to 7-9 wks in Atp8b1 mutant lungs and validated our microarray findings (Figure 7E). Lastly, a 4-fold increase in Mmp13 transcript was observed at 14 M in Atp8b1 mutant lungs (Figure 7F).

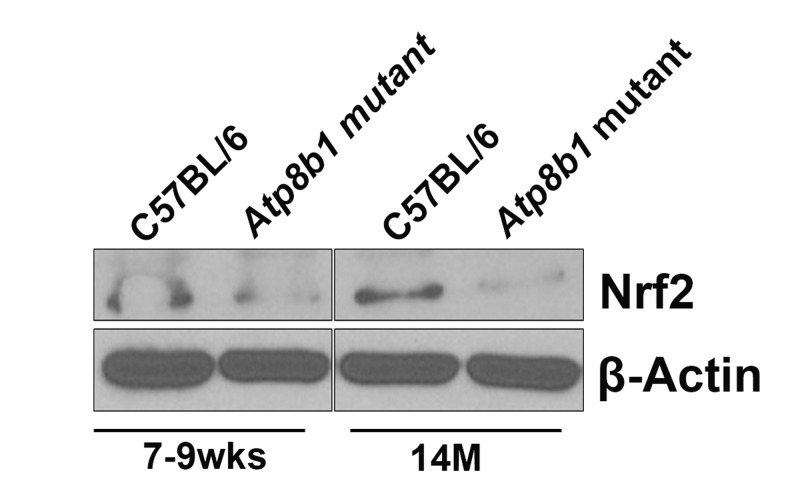

Nrf2 protein levels are decreased in aged Atp8b1 mutant lungs

Based on our microarray data, antioxidant Nrf2 target gene, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1 (NQO1) transcript was decreased significantly in aged Atp8b1 mutant lungs. As we were interested in exploring the Nrf2 pathway in detail, we carried out Western blot analysis of Nrf2 protein and detected a 110 kDa protein as described [20]. We found that at 7-9 wks, there was no change in Nrf2 protein in C57BL/6 or Atp8b1 mutant lungs (Figure 8). Interestingly at 14 M, in Atp8b1 mutant lungs, there was a decrease in Nrf2 protein relative to C57BL/6 control (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Western blot analysis of Nrf2.

Equal amounts of protein from C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant lung homogenates (7-9 wks and 14 M timepoints) were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-Nrf2 antibody. There was no change in Nrf2 protein levels at 7-9 wks in both the groups. There was a significant decrease in Nrf2 protein in Atp8b1 mutant lungs at 14 M compared to C57BL/6 control. This is a representative blot. The experiment was repeated three times. β–Actin used as a loading control shows equal loading in all the lanes.

DISCUSSION

Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with aging [9]. Cardiolipin, a phospholipid found in the inner mito-chondrial membrane, is vital for overall mitochondrial function and maintenance of membrane potential and integrity. In many pathological conditions associated with aging, there is alteration in the structure and content of cardiolipin leading to mitochondrial dysfunction [11]. Atp8b1 is a cardiolipin transporter in type II AECs [15]. The G308V mutation leads to a functional deficiency in Atp8b1 via aberrant folding of Atp8b1 in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and decreased expression of Atp8b1 in the plasma membrane [15, 21]. Therefore, Atp8b1 mutant proteins expressed in type II AECs are defective in cardiolipin transport. Further, mutation in Atp8b1 or lung inflammation is associated with increased secretion of cardiolipin in airways and also development of pneumonia [15]. In this study, we examined age-related genes by global transcriptome analysis of lung tissue derived from Atp8b1 mutant and C57BL/6 mice. Studies from our lab indicate that Atp8b1 mutant mice are more susceptible to oxidative stress-induced lung injury during hyperoxia (unpublished observations). Therefore, we were interested in studying the transcriptome of Atp8b1 mutant mice at 7-9 wks and 14 M to elucidate age-related changes that contribute to disease susceptibility.

Comparison of Atp8b1 mutant lungs at 7-9 wk and 14 M revealed 537 differentially expressed genes relative to the 157 observed in the C57BL/6 lung samples. Of these, 37 genes overlapped between Atp8b1 mutant and C57BL/6 lung samples indicating common age-related genes between these genotypes. The overlapping genes including Akap13, Atrx, Col1a1, Col3a1, Ddx6, Luzp1, Rian, Sema5a, and Sfb31, which decreased with aging; whereas transcripts including Cxcr6 and Slc6A20 increased with aging. In both C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutants, collagen producing genes such as Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, and Col5a1 were decreased during aging. These findings are in agreement with a study wherein age-related changes in collagen production and degradation were observed in aging rat lungs [19].

One of the strengths of our study is that we used Atp8b1 mutant mice on C57BL/6 background and compared them to C57BL/6 normal controls. The effect of mouse strain background in aged lungs has previously revealed some major differences between C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice [9]. There was an up-regulation of stress-related genes including xenobiotic detoxification system in DBA/2 mice; whereas in C57BL/6 mice, there was a down-regulation of heat-shock genes. There was also an age-dependent down-regulation of collagen genes in both strains [9]. Gene profiling studies in various aging mouse models reveal up-regulation of stress-response genes including heat-shock response and oxidative-stress inducible genes [8, 11].

Furthermore, a majority of gene changes were observed only in Atp8b1 mutant lungs relative to the C57BL/6 controls and may be attributed to both the effect of mutation and aging (14 M). IPA analysis revealed distinct changes in the canonical and non-canonical signaling pathways in aged Atp8b1 mutant mice relative to the aged C57BL/6 controls. Some of the important canonical pathways altered in Atp8b1 mutants included xenobiotic metabolism, Nrf2, calcium, and RhoGD1 signaling. The majority of the signaling molecules in these pathways were decreased in Atp8b1 mutant lungs. In contrast, some of the canonical pathways altered in C57BL/6 were: RhoA, PI3K/Akt, EGF, PDGF, Jak/Stat, iNOS, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. The RhoA pathway was altered in both Atp8b1 mutant and C57BL/6 lungs during aging. RhoA is an important signaling molecule that plays a pivotal role in cell proliferation, growth, adhesion, and also calcium sensitivity. An age related increase in both RhoA transcript and protein content was observed in the aortic and basilar arteries in rats [22]. This suggests that RhoA may play an important role in vascular responses associated with aging including: injury and/or cell proliferation and migration. Besides, RhoA is known to regulate the actin cytoskeleton and is involved in cell cycle progression and gene regulation [23]. Previously, it has been demonstrated that Rho signaling mediates both growth factor expression in fibroblasts and formation of myofibroblast in IPF lungs [24, 25]. The importance of RhoA signaling in modulating Cyclin D1 expression in IPF-derived fibroblasts and its effect on fibroblast proliferation has also been reported [26]. Moreover, age-related diseases, such as IPF, may share some common pathophysio-logical mechanism with normal lung aging [1, 27, 28]. Therefore, it is plausible that an increase in RhoA transcript in both aged Atp8b1 mutant and aged C57BL/6 mice may be associated with response against cell injury, proliferation, or migration.

In addition, Rac and Rho transcripts were significantly increased in aged Atp8b1 mutant mice. Rac and Rho proteins are involved in non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway. In contrast, the gene encoding cAMP-response element binding protein (CREBP), which forms a complex with β-catenin and acts as a transcriptional co-activator in canonical Wnt signaling pathway, was significantly decreased in Atp8b1 mutant mice in an age-dependent manner. Wnt signaling pathways have been associated with replicative senescence that is one of the hallmarks of aging [29]. Our observation that canonical Wnt signaling decreased in Atp8b1 mutant lungs is in concordance with another study wherein a decrease in Tle1 and Lef1 transcripts and increase in Frzb, encoding an extracellular Wnt ligand inhibitor, were observed in 24 M lungs relative to 5 M lungs [30]. The decline of Wnt signaling has been associated with several age-related diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease [31], and osteoporosis [32, 33]. This may be attributed to the important role of Wnt signaling in the maintenance of stem cell homeostasis and delay of aging. On the other hand, over activation of Wnt signaling has been reported to result in tissue fibrosis [34]. Based on our data and the previous report [30], we observe a decline in the Wnt pathway.

In addition, Adamts2, a transcript encoding a disintegrin metalloprotease with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 2 linked to ECM, was found to be decreased in aged Atp8b1 mutant lungs. This is in agreement with another study where genes encoding collagen and ECM showed a decrease with age in both wild type mouse strains (DBA/2J and C57BL6/J) [35,19]. Matrix metallo-proteinases (MMPs) play an important role in fibrosis and tissue remodeling. MMPs regulate deposition and resorption of collagen and other ECM components. The turnover of ECM is determined by the ratio of MMPs and the tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs) [36]. We speculate that in Atp8b1 mutant mice, the age-dependent reduction in collagen isoforms may be linked to the aberrant re-modeling of ECM by MMPs and TIMPs. Further, the transcriptome profile of Atp8b1 mutant lungs revealed increased expression of Mmp12 and Mmp13 mRNAs that encode metalloproteinases MMP12 and MMP13, respectively. MMP12 is a macrophage-specific metallo-proteinase that specifically degrades elastin and has been associated with chronic degenerative emphysema [37]. In addition, the gene profiling of mice that lack integrin b6 subunit of the αvβ6 integrin showed an 18-fold increase in Mmp12 [38]. The deficiency of integrin αvβ6-mediated TGF-β activation leads the mice to spontaneously develop emphysema at 14M of age in a MMP12 dependent manner [38]. In light of this finding, Atp8b1 mutant mice may be susceptible to develop age-induced emphysema as a result of increased MMP12 levels. Interestingly, in an asbestos-induced mouse model of lung injury, the collagenase MMP13 has been shown to play a key role in the development of severe inflammation and fibrosis [39]. Moreover, MMP13 knockout mice have been shown to exhibit reduced radiation-mediated inflammation and fibrosis [40]. Interestingly, MMP13 is highly upregulated in IPF patient lungs and its spatially imbalanced collagenolytic activity in airways results in the development of characteristic honeycomb cysts [6]. This suggests that Atp8b1 mutant mice may be susceptible to age-induced lung fibrosis mediated in part by MMP13.

In a Schistosoma mansoni model of pulmonary fibrosis, Madala and colleagues demonstrate the intricate balance between MMP12 and MMP13 in modulating TH2-dependent lung and liver fibrosis [41]. They show that in MMP12 −/− mice, there was a marked increase of MMP13 after S. mansoni egg challenge. In addition, they show that MMP12 may negatively regulate MMP13 expression in liver and lung. Further, MMP12 expression was dependent upon IL-4/IL-13 signaling [41]. It would be interesting to explore IL-4 and IL-13 signaling in our Atp8b1 mutant mouse model as well as check whether TH2 predominates over TH1 response in our model. Though the TGF-β signaling pathway is implicated in lung fibrosis, in their model of parasite-induced fibrosis, TGF-β signaling was not implicated. In concordance with this and previous studies, we did not observe any transcriptome changes in TGF-β signaling with aging in either C57BL/6 or Atp8b1 mutant mice [34].

Excessive production of ROS has been linked to age-related diseases such as COPD, IPF, and lung fibrosis [3, 4, 6]. ROS-mediated accelerated aging also induces chronic inflammation in COPD lungs [4]. The inflammation associated with COPD or other chronic inflammatory lung diseases is attributed to the loss of alpha1-antitrypsin function [42]. Interestingly, our gene profiling studies showed that the expression of Serpina1b, a gene that encodes for alpha1-anti-trypsin was up-regulated in aged Atp8b1 mutant mice. Further, alpha-1 antitrypsin is known to protect the lungs from neutrophil elastase. This indicates that the susceptibility of Atp8b1 mutant mice to inflammatory or age-related lung disease is not attributed to deficiency of alpha1-antitrypsin.

In addition, several endogenous antioxidant mechanisms are present to combat ROS-mediated damage in cells including the Nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2-antioxidant response element (Nrf2-ARE) pathway [5]. Antioxidant response element (ARE) is a cis-acting element found in the promoter region of several cytoprotective genes including GSTA2 (glutathione S-transferase A2) and NQO1 (NADPH: quinone oxidoreductase 1) [43]. The unique responsiveness to oxidative stress, changes in redox potential and elevated electrophilic species is a structural and biological feature of the ARE [44]. The transcription factor Nrf2 is a positive regulator of ARE and is expressed in epithelial and alveolar macrophages as it plays a vital role in protecting lungs from ROS-mediated injury via activation of ARE-induced cytoprotective genes [5]. The protective effect of Nrf2 against oxidative stress is supported by studies that show an increased incidence of cancer, pulmonary disease, and inflammation in Nrf2 knockout mice (reviewed in [45-47]). Interestingly, Nrf2 signaling plays a protective role in many of these age-relative diseases. Nrf2 protects against the development of pulmonary fibrosis by regulating the redox level in the cells and by maintaining Th1/Th2 balance [48]. In another related study, the targeting of the Nox4-Nrf2 pathway to restore the Nox4-Nrf2 redox balance in myofibroblasts was suggested as an effective therapeutic strategy in age-dependent fibrotic disorders [27]. In our study, we found that one such Nrf2 target gene, Nqo1 encoding NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1 (NQO1). was significantly decreased in aged Atp8b1 mutant lungs relative to control. This suggests that the Nrf2 anti-oxidant pathway may be perturbed in Atp8b1 mutant mice. It is plausible that this may account for the oxidative stress induced phenotype observed when these mice were treated with hyperoxia. Another anti-oxidant gene, Prdx6 encoding peroxiredoxin 6, involved in reducing phospholipid hydroperoxide was similarly decreased in Atp8b1 mutant lungs. PRDX6 protein is involved in redox regulation and protection of cells against oxidative injury in an ARE-dependent manner via the Nrf2 pathway.

In conclusion, our transcriptome analysis revealed distinct signaling pathways such as RhoA and Wnt, shown to be perturbed in aged lungs in both C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant mice. In addition, collagen producing genes such as Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a, and Col5a1 were also decreased during aging in both C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant mice. In addition, we observed age-related changes in Atp8b1 mutant mice transcriptome including Mmp12, Mmp13, Adamts2, Nrf2 signaling and xenobiotic signaling pathways. This suggests that some of the signaling pathways commonly affected in C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant mice can be attributed to the process of aging, whereas the transcripts affected only in Atp8b1 mutant mice with aging could be due to the combined effect of the Atp8b1 mutation and the aging process. Future studies will explore in greater detail whether Atp8b1 mutant mice are susceptible to age-related lung fibrosis and the molecular mechanisms underlying the disease processes.

METHODS

Ethics statement

Protocols using mice in this study were approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, IACUC (Animal Welfare Assurance Number: A4100-01) in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals” established by the National Institute of Health (NIH) (1996, Revised 2011).

Animals

Atp8b1G308V/G308V mutant mouse was a generous gift from Dr. Laura Bull (University of California, San Francisco). C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and were used as controls. Atp8b1G308V/G308V (N=6, 7-9 weeks old males; N=6, 7-9 weeks old females; and C57BL/6 (N=6, 14M old males) and (N=6, 14M old females) were maintained in a specific-pathogen-free animal facility at the University of South Florida. We provided water and standard food ad libitum.

Collection of mouse lungs

Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine/xylazine mixture. Following thoracotomy, the inferior vena cava (IVC) was clamped and 2 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was injected into the right ventricle for lung perfusion as previously described [2]. The lung samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Total RNA extraction

Total RNA from C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant lungs (7-9 wks and 14 M) was extracted using Trizol (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Tampa, FL) and RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as per manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications Briefly, lungs were homogenized in Trizol. This was followed by the extraction of aqueous phase using chloroform and precipitation of RNA using isopropanol. The precipitated RNA was dissolved in 30 μl of RNase-free water and subjected to purification using RNeasy columns as per manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). The quality of RNA was assessed in three ways, first by Agilent Bioanalyzer, second by testing for RNase activity and running samples on agarose gels, and third, by checking the absorbance of the total RNA by Nanodrop. RNA samples with 260/280 ratio of 1.8 to 2.0 and 260/230 ratio of > 2.0 were further considered for microarray analysis. The samples that passed all the three quality control (QC) tests were considered suitable for microarray processing.

Transcriptome analysis of lungs

Mouse Genome 430 v2.0 arrays (Affymetrix) contains over 45,000 probe sets designed from GenBank, dbEST, and RefSeq sequences that were clustered based on build 107 of the UniGene database. The clusters were further refined by comparison to the publicly available draft assembly of the mouse genome. An estimated 39,000 distinct transcripts are detected including over 34,000 well substantiated mouse genes. Each gene is represented by a series of oligonucleotides that are identical to the sequence in the gene as well as oligonucleotides that contain ahomomeric (base transversion) mismatch at the central base position of the oligomer, which is used to measure cross-hybridization. Microarray study was performed at the Molecular Genomics Core (MGC) at Moffitt Cancer Center. A brief procedure is as described below.

Sample processing and preparation of library

One hundred micrograms of total RNA was converted to cDNA, amplified and labeled with biotin using the Ambion Message Amp Premier RNA Amplification kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) as per manufacturer's protocol [49]. This was followed by hybridization with the biotin-labeled RNA, staining, and scanning of the chips as outlined in the Affymetrix technical manual and described previously [50].

Data analysis

Scanned output files were visually inspected for hybridization artifacts and then analyzed using Affymetrix Expression Console 1.4 software using the MAS 5.0 algorithm. Signal intensity was scaled to an average intensity of 500 before data export and filtering [51]. The data was further analyzed at Cancer Informatics Core at Moffitt Cancer Center.

Differential gene expression

The CEL files were normalized using pair-wise IRON (Iterative Rank-order normalization) method as described previously (http://gene.moffitt.org/libaffy) [52] and QC was checked using Sample-to-sample scatter plot and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for all samples and all variables (Strain, time-points, and gender). No outlier or batch effects were detected. The first five samples were all males. One sample was removed from further analysis (B6 7-9wks, Male 6) since the expression of gender specific genes did not match its annotated gender. For each probe set, the raw intensities were log2-transformed. Significantly differently expressed genes was defined as q<0.1 (false discovery rate corrected Mann-Whitney U test p-value) and if the median-value difference between two groups was larger than 1 (log2 expression units). Differentially expressed genes were further analyzed using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, (IPA) (Ingenuity Systems, Qiagen). MIAME compliant microarray data was submitted to Gene expression omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) and the assigned GEO Accession Number is (GSE80680).

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA)

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (IPA; Ingenuity Systems, www.ingenuity.com, Summer 2015 release, Qiagen) was used to identify gene networks affected in C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant mice at two different time-points (7-9 wk vs 14 M). Data that was uploaded into IPA included Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 V 2.0 probe sets as identifiers as well as processed microarray data sets. Using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, canonical pathways of differentially expressed genes that were most significant were identified. Only genes having q< 0.05 were used for analysis. Based on their connectivity to the uploaded data, gene networks were algorithmically generated using this software. In each network, the genes or molecules are represented as nodes, and the biological relationship between two nodes is represented as an edge (line). All edges are supported by at least one reference from the literature or canonical information stored in IPA knowledge base. The intensity of the node color indicates the degree of up- (red) or down- (green) -regulation with respect to the datasets. Nodes are displayed using various shapes that represent the functional class of the gene product.

Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit as per manufacturer's instructions (Biorad laboratories, Hercules, CA). We performed qRT-PCR with the SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix kit (Biorad) and gene-specific primers using the Biorad CFX96 Real-time system (C1000 Thermal Cycler). A relative fold change in gene transcript was calculated using the Biorad CFX Manager software, applying the comparative CT method (Delta CT) and expressed as 2−ddCT and using β–actin as an internal calibrator. Melting curve analysis was performed to determine the specific amplification of the target genes. The primers for qRT-PCR were designed using the mouse qPrimerDepot (http://mouseprimerdepot.nci.nih.gov). The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed (Table 4).

Table 4. Quantitative Real-time PCR primers.

| Gene | Primers (5′-3′) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| ActB | Forward: CCAGTTCGCCATGGATGACGATAT Reverse: GTCAGGATACCTCTCTTGCTCTG |

207 |

| Adamts2 | Forward: GCTCTGCTGAGGCTGTCC Reverse: CATGTGGTATATCGCCGACC |

107 |

| Col1a1 | Forward: GCAACAGTCGCTTCACCTACA Reverse: CAATGTCCAAGGGAGCCACAT |

137 |

| Cxcr6 | Forward: TGGAACAAAGCTACTGGGCT Reverse: AAATCTCCCTCGTAGTGCCC |

90 |

| Mmp13 | Forward: GGTCCTTGGAGTGATCCAGA Reverse: TGATGAAACCTGGACAAGCA |

98 |

Western blot analysis

Lung homogenates were prepared from C57BL/6 and Atp8b1 mutant mice (7-9 wks and 14 M ) as described previously [2]. Briefly, 50 μg of total proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Following blocking in Tris-buffered saline (20 mM Tris·HCl at pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl) with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) containing 5% skimmed milk, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4◦C with rabbit polyclonal anti-Nrf2 antibody as per manufacturer's recommendations (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Following washing of the membrane with TBS-T, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature. This was followed by washes with TBS-T, protein on the membranes was visualized using Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate as per manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hudson, NH). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated β-actin antibody (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was used as a loading control.

Statistical analysis

In this study, GraphPad Prism version 10.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analyses. We used Student's T-test to calculate statistical significance between two groups. p values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL TABLES

Footnotes

FUNDING

N. Kolliputi was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute R01 Grant HL 105932.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leung J, Cho Y, Lockey RF, Kolliputi N. The Role of Aging in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Lung. 2015;193:605–10. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9729-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukumoto J, Fukumoto I, Parthasarathy PT, Cox R, Huynh B, Ramanathan GK, Venugopal RB, Allen-Gipson DS, Lockey RF, Kolliputi N. NLRP3 deletion protects from hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C182–89. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00086.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuchi Y. The aging lung and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: similarity and difference. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:570–72. doi: 10.1513/pats.200909-099RM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercado N, Ito K, Barnes PJ. Accelerated ageing of the lung in COPD: new concepts. Thorax. 2015;70:482–89. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hybertson BM, Gao B, Bose SK, McCord JM. Oxidative stress in health and disease: the therapeutic potential of Nrf2 activation. Mol Aspects Med. 2011;32:234–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nkyimbeng T, Ruppert C, Shiomi T, Dahal B, Lang G, Seeger W, Okada Y, D'Armiento J, Günther A. Pivotal role of matrix metalloproteinase 13 in extracellular matrix turnover in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills E, O'Neill LA. Succinate: a metabolic signal in inflammation. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bratic A, Larsson NG. The role of mitochondria in aging. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:951–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI64125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osiewacz HD, Bernhardt D. Mitochondrial quality control: impact on aging and life span - a mini-review. Gerontology. 2013;59:413–20. doi: 10.1159/000348662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aravamudan B, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Mitochondria in lung diseases. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2013;7:631–46. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2013.834252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paradies G, Petrosillo G, Paradies V, Ruggiero FM. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial bioenergetics, and cardiolipin in aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:1286–95. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rooney SA, Young SL, Mendelson CR. Molecular and cellular processing of lung surfactant. FASEB J. 1994;8:957–67. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.12.8088461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrosillo G, Matera M, Casanova G, Ruggiero FM, Paradies G. Mitochondrial dysfunction in rat brain with aging Involvement of complex I, reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin. Neurochem Int. 2008;53:126–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrosillo G, Matera M, Moro N, Ruggiero FM, Paradies G. Mitochondrial complex I dysfunction in rat heart with aging: critical role of reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray NB, Durairaj L, Chen BB, McVerry BJ, Ryan AJ, Donahoe M, Waltenbaugh AK, O'Donnell CP, Henderson FC, Etscheidt CA, McCoy DM, Agassandian M, Hayes-Rowan EC, et al. Dynamic regulation of cardiolipin by the lipid pump Atp8b1 determines the severity of lung injury in experimental pneumonia. Nat Med. 2010;16:1120–27. doi: 10.1038/nm.2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen F, Ellis E, Strom SC, Shneider BL. ATPase Class I Type 8B Member 1 and protein kinase C zeta induce the expression of the canalicular bile salt export pump in human hepatocytes. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:183–87. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181c2df16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee CK, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Gene-expression profile of the ageing brain in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25:294–97. doi: 10.1038/77046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CK, Klopp RG, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Gene expression profile of aging and its retardation by caloric restriction. Science. 1999;285:1390–93. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5432.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mays PK, McAnulty R, Laurent GJ. Age-related changes in total protein and collagen metabolism in rat liver. Hepatology. 1991;14:1224–29. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840140643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau A, Tian W, Whitman SA, Zhang DD. The predicted molecular weight of Nrf2: it is what it is not. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:91–93. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Velden LM, Wichers CG, van Breevoort AE, Coleman JA, Molday RS, Berger R, Klomp LW, van de Graaf SF. Heteromeric interactions required for abundance and subcellular localization of human CDC50 proteins and class 1 P4-ATPases. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40088–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miao L, Calvert JW, Tang J, Parent AD, Zhang JH. Age-related RhoA expression in blood vessels of rats. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:1757–70. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(01)00297-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narumiya S. The small GTPase Rho: cellular functions and signal transduction. J Biochem. 1996;120:215–28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watts KL, Spiteri MA. Connective tissue growth factor expression and induction by transforming growth factor-beta is abrogated by simvastatin via a Rho signaling mechanism. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L1323–32. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00447.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watts KL, Sampson EM, Schultz GS, Spiteri MA. Simvastatin inhibits growth factor expression and modulates profibrogenic markers in lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:290–300. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0127OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watts KL, Cottrell E, Hoban PR, Spiteri MA. RhoA signaling modulates cyclin D1 expression in human lung fibroblasts; implications for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2006;7:88. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hecker L, Logsdon NJ, Kurundkar D, Kurundkar A, Bernard K, Hock T, Meldrum E, Sanders YY, Thannickal VJ. Reversal of persistent fibrosis in aging by targeting Nox4-Nrf2 redox imbalance. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:231ra47. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thannickal VJ, Loyd JE. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a disorder of lung regeneration? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:663–65. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1127ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye X, Zerlanko B, Kennedy A, Banumathy G, Zhang R, Adams PD. Downregulation of Wnt signaling is a trigger for formation of facultative heterochromatin and onset of cell senescence in primary human cells. Mol Cell. 2007;27:183–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmann JW, McBryan T, Adams PD, Sedivy JM. The effects of aging on the expression of Wnt pathway genes in mouse tissues. Age (Dordr) 2014;36:9618. doi: 10.1007/s11357-014-9618-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berwick DC, Harvey K. The importance of Wnt signalling for neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:1123–28. doi: 10.1042/BST20120122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almeida M, Han L, Martin-Millan M, O'Brien CA, Manolagas SC. Oxidative stress antagonizes Wnt signaling in osteoblast precursors by diverting beta-catenin from T cell factor- to forkhead box O-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27298–305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett CN, Longo KA, Wright WS, Suva LJ, Lane TF, Hankenson KD, MacDougald OA. Regulation of osteoblastogenesis and bone mass by Wnt10b. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3324–29. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408742102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chilosi M, Poletti V, Zamò A, Lestani M, Montagna L, Piccoli P, Pedron S, Bertaso M, Scarpa A, Murer B, Cancellieri A, Maestro R, Semenzato G, Doglioni C. Aberrant Wnt/beta-catenin pathway activation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1495–502. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64282-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Misra V, Lee H, Singh A, Huang K, Thimmulappa RK, Mitzner W, Biswal S, Tankersley CG. Global. expression profiles from C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mouse lungs to determine aging-related genes. Physiol Genomics. 2007;31:429–40. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00060.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wynn TA. Common and unique mechanisms regulate fibrosis in various fibroproliferative diseases. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:524–29. doi: 10.1172/JCI31487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaminski N, Allard JD, Pittet JF, Zuo F, Griffiths MJ, Morris D, Huang X, Sheppard D, Heller RA. Global analysis of gene expression in pulmonary fibrosis reveals distinct programs regulating lung inflammation and fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1778–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris DG, Huang X, Kaminski N, Wang Y, Shapiro SD, Dolganov G, Glick A, Sheppard D. Loss of integrin alpha(v)beta6-mediated TGF-beta activation causes Mmp12-dependent emphysema. Nature. 2003;422:169–73. doi: 10.1038/nature01413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan RJ, Fattman CL, Niehouse LM, Tobolewski JM, Hanford LE, Li Q, Monzon FA, Parks WC, Oury TD. Matrix metalloproteinases promote inflammation and fibrosis in asbestos-induced lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:289–97. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0471OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flechsig P, Hartenstein B, Teurich S, Dadrich M, Hauser K, Abdollahi A, Gröne HJ, Angel P, Huber PE. Loss of matrix metalloproteinase-13 attenuates murine radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:582–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madala SK, Pesce JT, Ramalingam TR, Wilson MS, Minnicozzi S, Cheever AW, Thompson RW, Mentink-Kane MM, Wynn TA. Matrix metalloproteinase 12-deficiency augments extracellular matrix degrading metalloproteinases and attenuates IL-13-dependent fibrosis. J Immunol. 2010;184:3955–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lomas DA, Hurst JR, Gooptu B. Update on alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: new therapies. J Hepatol. 2016;65:413–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rushmore TH, King RG, Paulson KE, Pickett CB. Regulation of glutathione S-transferase Ya subunit gene expression: identification of a unique xenobiotic-responsive element controlling inducible expression by planar aromatic compounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3826–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen T, Nioi P, Pickett CB. The Nrf2-antioxidant response element signaling pathway and its activation by oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13291–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900010200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sykiotis GP, Bohmann D. Stress-activated cap'n'collar transcription factors in aging and human disease. Sci Signal. 2010;3:re3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3112re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee JM, Li J, Johnson DA, Stein TD, Kraft AD, Calkins MJ, Jakel RJ, Johnson JA. Nrf2, a multi-organ protector? FASEB J. 2005;19:1061–66. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2591hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:549–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kikuchi N, Ishii Y, Morishima Y, Yageta Y, Haraguchi N, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Hizawa N. Nrf2 protects against pulmonary fibrosis by regulating the lung oxidant level and Th1/Th2 balance. Respir Res. 2010;11:31. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Gelder RN, von Zastrow ME, Yool A, Dement WC, Barchas JD, Eberwine JH. Amplified RNA synthesized from limited quantities of heterogeneous cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1663–67. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Warrington JA, Nair A, Mahadevappa M, Tsyganskaya M. Comparison of human adult and fetal expression and identification of 535 housekeeping/maintenance genes. Physiol Genomics. 2000;2:143–47. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2000.2.3.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu WM, Mei R, Di X, Ryder TB, Hubbell E, Dee S, Webster TA, Harrington CA, Ho MH, Baid J, Smeekens SP. Analysis of high density expression microarrays with signed-rank call algorithms. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1593–99. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.12.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Welsh EA, Eschrich SA, Berglund AE, Fenstermacher DA. Iterative rank-order normalization of gene expression microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:153. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.