Abstract

The inositol pyrophosphate messengers (PP-InsPs) are emerging as an important class of cellular regulators. These molecules have been linked to numerous biological processes, including insulin secretion and cancer cell migration, but how they trigger such a wide range of cellular responses has remained unanswered in many cases. Here, we show that the PP-InsPs exhibit complex speciation behaviour and propose that a unique conformational switching mechanism could contribute to their multifunctional effects. We synthesised non-hydrolysable bisphosphonate analogues and crystallised the analogues in complex with mammalian PPIP5K2 kinase. Subsequently, the bisphosphonate analogues were used to investigate the protonation sequence, metal-coordination properties, and conformation in solution. Remarkably, the presence of potassium and magnesium ions enabled the analogues to adopt two different conformations near physiological pH. Understanding how the intrinsic chemical properties of the PP-InsPs can contribute to their complex signalling outputs will be essential to elucidate their regulatory functions.

Keywords: biological activity, conformation analysis, phosphorylation, protonation, signal transduction

Introduction

Secondary messengers are key regulators within cellular signal transduction networks. Related to the lipid-anchored phosphatidyl inositol signalling molecules, but less well characterised, are the soluble inositol polyphosphates and inositol pyrophosphates (PP-InsPs).[1] The latter group of densely phosphorylated molecules is particularly notable because the members bear one or two highly energetic diphosphate groups attached to the myo-inositol scaffold.[2] The large amount of energy necessary for their biosynthesis, combined with their rapid cellular turnover, strongly suggests a central signalling role for the PP-InsPs.[3]

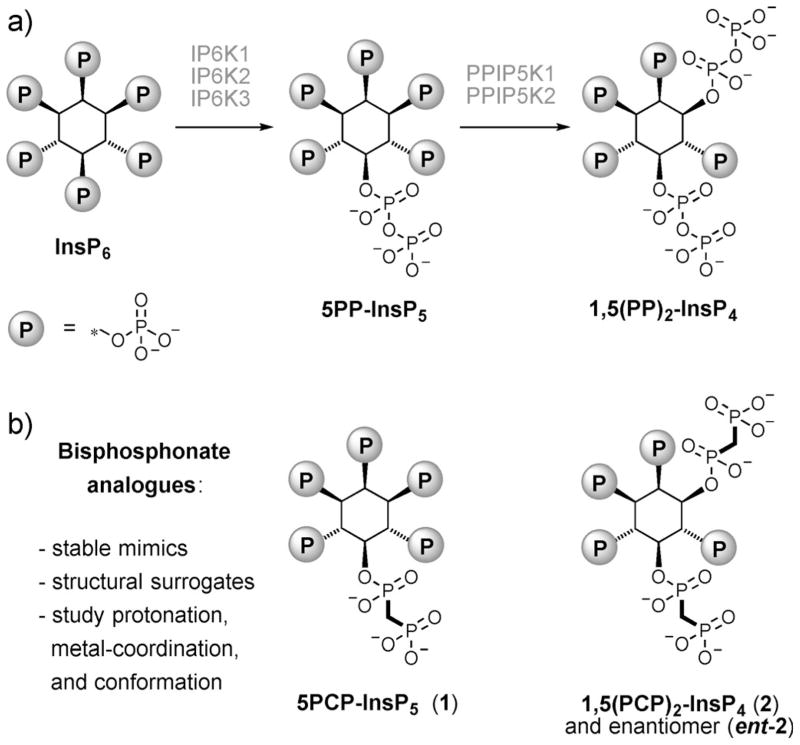

The canonical biosynthetic pathway for PP-InsPs in mammalian cells depends on the action of two unrelated families of small molecule kinases. First, inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6) is converted into 5-diphosphoinostiol pentakisphosphate (5PP-InsP5) by inositol hexakisphosphate kinases IP6K1, 2, and 3 (Figure 1a).[4] Subsequently, the ATP-grasp enzymes PPIP5K1 and PPIP5K2 further phosphorylate 5PP-InsP5 to yield 1,5-bis-(diphosphoinositol) tetrakisphosphate (1,5(PP)2-InsP4, also called InsP8, Figure 1a).[5] Compared with the InsP6 precursor, the cellular concentrations of the inositol pyrophosphates 5PP-InsP5 and 1,5(PP)2-InsP4 are low (InsP6: 30–50 μM, 5PP-InsP5: 1–2 μM, 1,5(PP)2-InsP4 : <1 μM), which may be attributed to the rapid enzymatic hydrolysis of the PP-InsPs by diphosphoinositol polyphosphate phosphohydrolases (DIPPs).[2, 6]

Figure 1.

Inositol pyrophosphates and their corresponding bisphosphonate analogues. a) Abbreviated biosynthetic pathway to generate the messengers 5-diphosphoinositol pentakisphosphate (5PP-InsP5), and 1,5-bis(diphosphoinositol) tetrakisphosphate (1,5(PP)2-InsP4). b) Bisphosphonate analogues reported here, and their applications.

Characterisation of cell lines and organisms with perturbed PP-InsP biosynthesis has uncovered a regulatory function of these molecules in a wide range of cellular processes. For example, in S. cerevisiae the PP-InsPs play a role in ribosome biogenesis,[7] telomere maintenance,[8] and phosphate sensing.[9] In higher eukaryotes, the PP-InsPs are critical components in cancer cell migration and metastasis,[10] insulin secretion,[11] insulin sensitivity,[12] and host-cell immune response during viral invasion.[13] How these messengers are able to elicit such a broad spectrum of cellular responses has remained a topic of active debate. Interestingly, the PP-InsPs can utilise two distinct signalling mechanisms: protein binding and protein pyrophosphorylation.[ 2, 7, 14] In addition, the PP-InsPs are likely to interact strongly with metal cations intracellularly,[15] which would result in the formation of different PP-InsP-metal complexes. Finally, the highly phosphorylated inositols and 5PP-InsP5 were shown to undergo a conformational change at high pH, which could also contribute to their multifaceted outputs.[16]

This complex picture has sparked an interest in chemical tools that can be utilised to unravel the underlying signalling properties of the PP-InsPs. To this end, our group has pursued the synthesis and characterisation of non-hydrolysable bisphosphonate analogues of the PP-InsPs, and we previously described bisphosphonate analogues 5PCP-InsP5 and 1PCP-InsP5.[16e, 17] Now we report improved synthetic access to 5PCP-InsP5 (1), and the synthesis of bisphosphonate analogues for both enantiomers of InsP8, 1,5(PCP)2-InsP4 and 3,5(PCP)2-InsP4 (Figure 1b, 2 and ent-2). The analogues were characterised structurally by co-crystallisation with PPIP5K2 kinase, revealing close structural mimicry of the bisphosphonate analogues when compared with the natural molecules. Given that the bisphosphonate group can withstand a wide pH range and is not hydrolysed by the presence of Lewis acidic metal cations,[16e, 17–19] we subsequently utilised the analogues to investigate their protonation states, their cation chelating properties, and their conformation in solution.

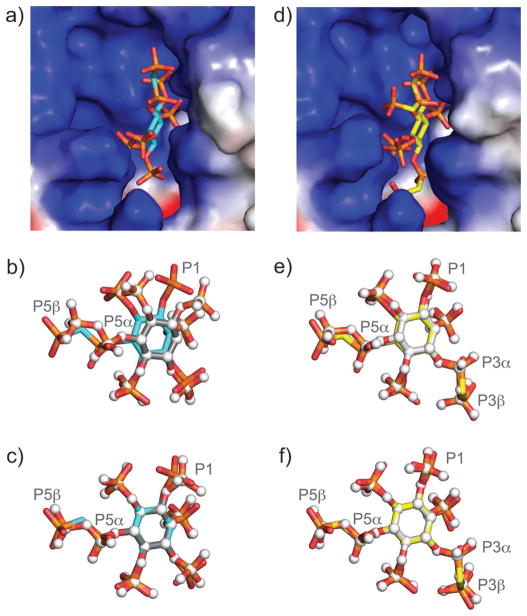

Figure 2.

Structural analysis of bisphosphonate analogues in complex with PPIP5K2. a) Electrostatic surface presentation of the active site of PPIP5K2 with 5PCP-InsP5 bound. b) Superimposition of the catalytic domains of PPIP5K2 bound to 5PCP-InsP5 (cyan C–C bonds) or 5PP-InsP5 (grey C–C bonds and white spheres for all atoms). c) Superimposition of the carbon atoms of the inositol ring in 5PCP-InsP5 (cyan C–C bonds) or 5PP-InsP5 (grey C–C bonds and white spheres for all atoms). d) Electrostatic surface presentation of the active site of PPIP5K2 with 3,5(PCP)2-InsP4 bound. e) Superimposition of the catalytic domains of PPIP5K2 bound to 3,5(PCP)2-InsP4 (yellow C–C bonds) or 3,5(PP)2-InsP4 (white C–C bonds and white spheres for all atoms). f) Superimposition of the carbon atoms of the inositol ring in 3,5(PCP)2-InsP4 (yellow C–C bonds) or 3,5(PP)2-InsP4 (white C–C bonds and white spheres for all atoms).

Notably, potassium and magnesium ions had a significant influence on the conformational preferences of the bisphosphonate analogues, enabling the molecules to adopt two different conformations near physiological pH. Our findings suggest that a conformational switching mechanism could effectuate multifunctional properties of the inositol pyrophosphate messengers in a cellular setting.

Results and Discussion

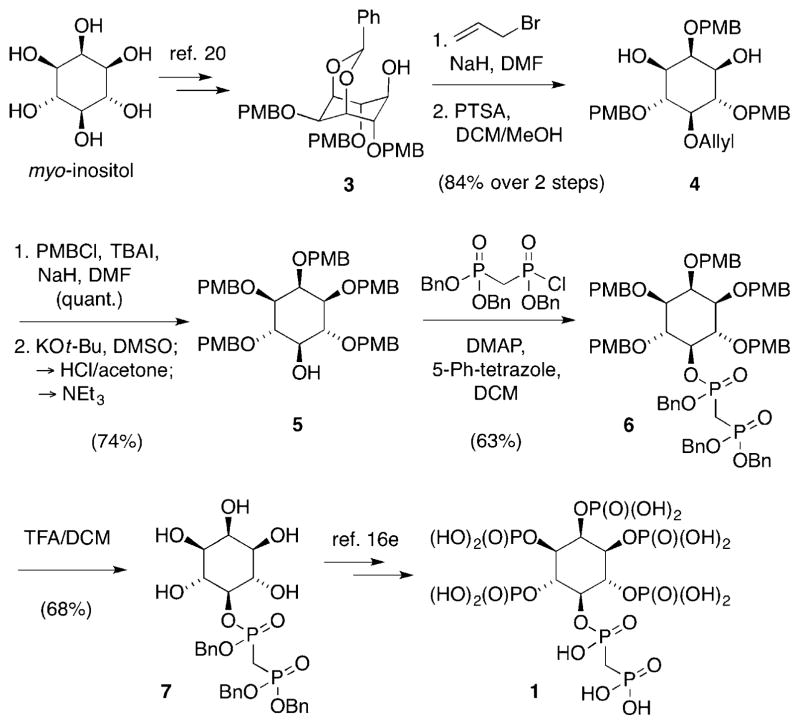

Synthesis of 5PCP-InsP5

Our group previously reported the synthesis of bisphosphonate analogue 5PCP-InsP5 (1), in which the pyrophosphate group is replaced by a bisphosphonate moiety.[16e] The synthesis, although effective, involved an elaborate separation of regioisomers early on in the procedure. We therefore sought to devise a more efficient approach, utilising acetal 3 (Scheme 1). This intermediate was reported by Holmes and co-workers, and can be obtained from myo-inositol in two steps.[20] Along this strategy, allylation of 3, followed by acetal cleavage, formed allyl ether 4 in 84% yield. para-Methoxybenzyl (PMB) protection of the hydroxyl groups and removal of the allyl protecting group provided reliable and scalable synthetic access to alcohol 5, which was then converted into the bisphosphonate-containing intermediate 6. Despite the steric hindrance around the secondary alcohol in 5, the bisphosphonate group could be attached in good yield, using 4-(N,N-dimethylamino)-pyridine (DMAP) and 5-phenyltetrazole (5-Ph-tetrazole) in dichloromethane. Removal of PMB groups from 6 furnished pentaol 7, which is an intermediate that we had previously employed in the synthesis of 5PCP-InsP5. Phosphitylation, oxidation, and hydrogenolysis ultimately afforded 1 in good yield and high purity.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 5PCP-InsP5 (1).

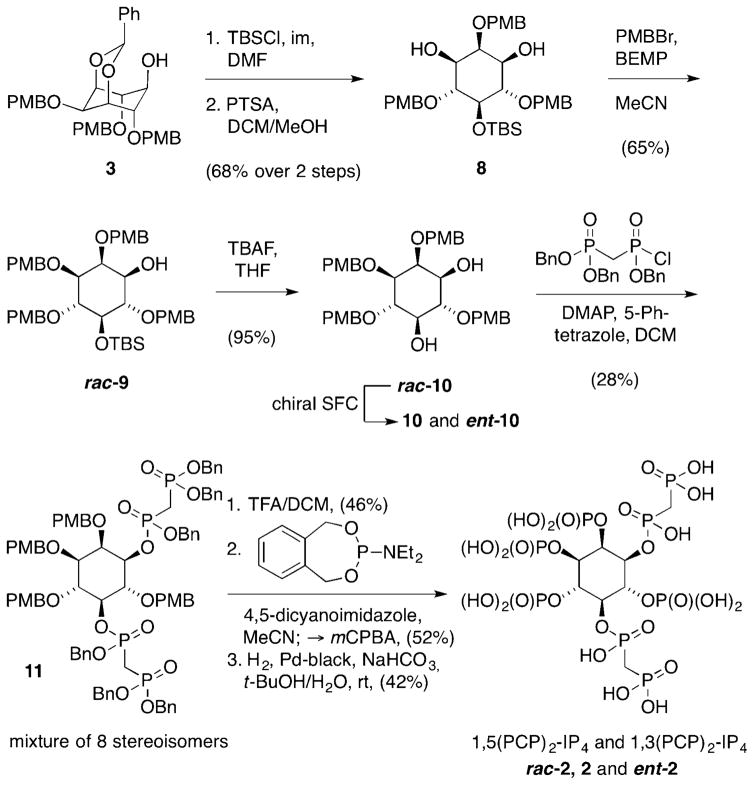

Synthesis of 1,5-(PCP)2-InsP4 and 3,5-(PCP)2-InsP4

The synthesis of the bisphosphonate analogues of the InsP8 enantiomers 1,5-(PCP)2-InsP4 and 3,5-(PCP)2-InsP4 was of higher synthetic complexity (Scheme 2). In the first step, the hydroxyl group in acetal 3 was protected as tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS) ether. Acetal cleavage delivered symmetric diol 8 in 68% yield over two steps. The envisioned mono-PMB-protection of this diol was more difficult than initially expected, and many reaction conditions led to product mixtures or TBS deprotection. Eventually, using phosphazene BEMP (2-tert-butylimino-2-diethylamino-1,3-dimethylperhydro-1,2,3-diazaphosphorine) as a base, and freshly prepared PMB bromide, alcohol rac-9 could be accessed in 65% yield. Removal of the TBS group provided the unsymmetrical diol rac-10, as a key intermediate of the synthesis, in almost quantitative yield. The subsequent attachment of the bisphosphonate groups was challenging because the diol system is highly sterically encumbered. In addition, the desired product features two additional stereogenic centres, resulting in a mixture of eight stereoisomers, which were complex to purify. We ultimately developed a protocol that relied on the continuous addition of an excess of the reagents, allowing us to isolate bisphosphonate rac-11 in 28% yield as a diastereomeric mixture. Global removal of PMB protecting groups provided the tetraol intermediate, which could be phosphitylated and oxidised in a one-pot procedure. The protected rac-(PCP)2-InsP4 was then hydrogenated, and subsequent ion-exchange provided access to the desired non-hydrolysable InsP8 mimic rac-2. To obtain the corresponding enantiomers, the racemic mixture of rac-10 was resolved by using preparative chiral supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC). Compound 10 and ent-10 were subsequently subjected to the synthetic sequence described above, to yield enantiomerically pure non-hydrolyzable analogues 2 and ent-2. Although the optical rotations for 2 and ent-2 (see the Supporting Information) were of similar magnitude but with opposite rotation, assignment of the absolute configuration solely based on comparison of these values to related compounds in the literature is difficult. Given that optical rotation values can strongly depend on pH and counter ion composition, we employed X-ray crystallography to determine the absolute configuration.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 1,5-(PCP)2-InsP4 and 3,5-(PCP)2-InsP4.

Crystallographic analysis of PCP analogues bound to PPIP5K2

To obtain structural information on the bisphosphonate analogues, both 1 and ent-2 were co-crystallised with the kinase domain of human PPIP5K2 (PPIP5K2KD). PPIP5K2 is a member of an evolutionarily-conserved family of kinases responsible for the conversion of 5PP-InsP5 into 1,5-(PP)2-InsP4,[5] and crystallographic data for both substrate and enzymatic product in complex with PPIP5K2KD, as well as the unnatural enantiomer 3,5(PP)2-InsP4, were reported recently.[21]

The structure of 5PCP-InsP5 (1) revealed that the analogue binds to the highly positively charged active site (Figure 2a). Superimposition of the structure with the corresponding catalytic domain of PPIP5K2 in complex with 5PP-InsP5 showed that the bisphosphonate analogue was captured in a very similar orientation, and the bisphosphonate group occupied the same pocket as the diphosphate group of 5PP-InsP5 (Figure 2b). The highest deviation between the structures was seen for the phosphate group in the 1-position. When the carbon atoms of the inositol rings in the two structures were superimposed, very good structural overlap was observed, and the bisphosphonate group adopts a conformation almost identical to that of the diphosphate moiety (Figure 2c, RMSD = 0.041 Å).

The structure of InsP8 analogue ent-2 in complex with PPIP5K2 served to determine the absolute configuration of the molecule. Enantiomer ent-2 turned out to be 3,5(PCP)2-InsP4; the electron density map provided an unequivocal assignment.[22] Consequently, 2 must be 1,5-(PCP)2-InsP4, which was subsequently confirmed by crystallisation (Figure S1). Just as in the case of the natural molecules, the bisphosphonate analogues were also accommodated in the positively charged active site of the kinase (illustrated for 3,5(PCP)2-InsP4 in Figure 2d). Superimposition of kinase domain bound to either 3,5(PCP)2-InsP4 or 3,5(PP)2-InsP4 showed excellent overlap of the analogue with 3,5(PP)2-InsP4 (Figure 2e). The structural mimicry of the bisphosphonate analogue is further substantiated by the superimposition of the carbon atoms of the inositol ring (Figure 2f, RMSD=0.034 Å), which shows that both bisphosphonate groups closely align with the diphosphate groups. The methylene group provides sufficient flexibility so that the oxygen atoms of the β-phosphoryl moieties are well superimposable with the oxygen atoms of the diphosphate groups.

Overall, the structural analysis of compounds 1 and ent-2 illustrated a close resemblance of the analogues to the corresponding diphosphate-containing molecules. Whereas the substitution of an oxygen atom for a methylene group can be associated with significant changes to the properties of a bisphosphonate analogue, such as for example altered pKa values and bond angles in the ATP analogue AMPPCP,[18, 23] the PCP-InsP analogues described here constitute very good mimics from a structural perspective. The data thus bodes well for future applications of the PCP-InsPs in crystallisation experiments, or for the development of these analogues into affinity reagents to identify protein binding partners.

pH-Dependent behaviour of 5PCP-InsP5 in solution in a non-interacting medium

With good quantities of 5PCP-InsP5 (1) in hand, and having ascertained that the compound constituted a good structural mimic, we wanted to obtain a detailed view of the protonation equilibria, the metal-coordination properties, and the conformation of 1. A qualitative comparison of analogue 1 with naturally occurring 5PP-InsP5 previously conducted by our group illustrated that the behaviour of the two molecules in solution is highly similar.[16e] PCP-analogue 1 is well suited for quantitative thermodynamic studies, because a constant concentration of 5PCP-InsP5 is required throughout the experiments, and the bisphosphonate group is stable over a wide pH range, and is resistant to hydrolysis mediated by Lewis acidic metal cations.[16e, 17–19] Given the number of metal cations that have to be considered in a biological setting, we decided to successively introduce complexity into the system by investigating the properties of 1 under the following conditions: a) in aqueous solution, without coordinating metal cations present; b) with added potassium ions; c) in the presence of potassium and magnesium ions; d) under cellular concentrations of sodium, potassium and magnesium.

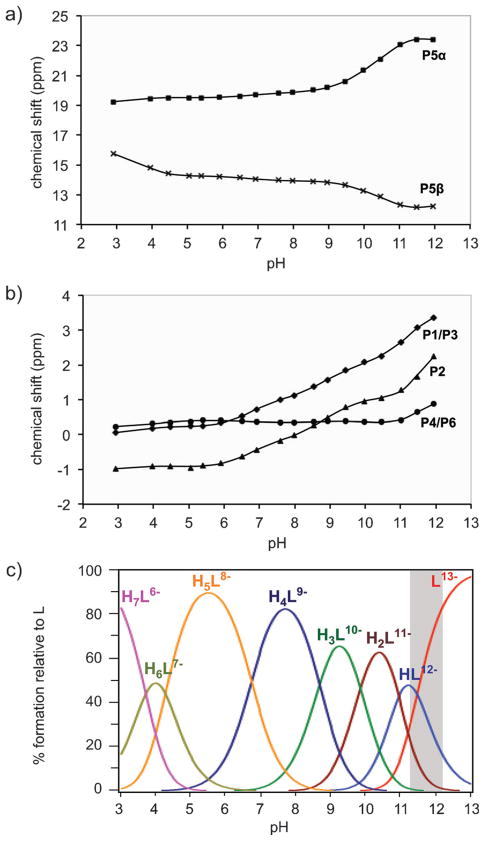

To elucidate the protonation sequence of 1 in the absence of coordinating counter ions, a 31P NMR titration was conducted at constant ionic strength (1 mM 1, 150 mM NMe4Cl, pH 3.0–13.0). Due to the symmetry of 1, three resonances were detected for the phosphate groups at positions 1 and 3 (P1/P3), 2 (P2), and 4 and 6 (P4/P6), as well as two signals corresponding to the bisphosphonate moiety (P5α and P5β). The changes in 31P NMR chemical shift with altered pH are depicted in Figure 3a and 3b. With the exception of P5β, the signals move downfield with increasing pH; an effect that was also observed for the related molecule InsP6.[24]

Figure 3.

NMR titration of 5PCP-InsP5 (1) without coordinating counter ions. a) and b) 31P NMR chemical shifts of 1 as a function of pH, measured in 0.15M NMe4Cl at 22.0 °C. Solid lines indicate the chemical shifts predicted by HypNMR, according to the protonation constants given in Table S1. c) Corresponding species distribution diagram of 1. Predictions are for [L]=1.0 mM. The pH range of the ligand conformational change is highlighted in grey.

Analysis of the NMR titration curves using HypNMR software[25] provided the first seven protonation constants of fully deprotonated 1 (L13−, Table S2). The solid lines in Figure 3a and 3b indicate the calculated chemical shifts of P1/P3, P2, P4/P6, P5α and P5β, based on the derived protonation constants, and illustrate an excellent fit to the experimental values. The corresponding species distribution diagram (Figure 3c) shows that the highly negatively charged H4L9− is the most abundant species in solution near pH 7.2.[26]

The calculated 31P NMR chemical shifts for the different species can be used to determine the protonation sites.[24] Given that protonation has a shielding effect on the 31P nuclei, analysis of the change in chemical shifts (ΔδP, Table S3) of P1/P3, P2, P4/P6, P5α and P5β, during successive protonation provides important information on the actual location of the protons. For example, during the transition from HL12− to H2L11−, the most negative ΔδP values were observed for P5α and P1/P3 (Table S3), indicating that these two phosphoryl groups were protonated during this proton rearrangement step. The predicted most abundant microspecies and their protonation sites are shown in Figure S3, along with a detailed explanation of the procedure.

Notably, during the first protonation, the chemical shifts of almost all resonances decreased significantly, suggesting a conformational change of the ligand. In its fully deprotonated state, 5PCP-InsP5 was previously shown to adopt a conformation with five phosphate groups in axial positions and the 2-phosphate group in an equatorial position (5a1e).[16e] Addition of the first proton causes a flip from a 5a1e to a 1a5e (1 axial, 5 equatorial) conformation (Figure 4a), consistent also with the broadening of the 31P NMR signals that is observed between pH 11.5 and 12.5. The pH zone in which HL12− and L13−, and thus both conformers, co-exist, is highlighted in the species distribution diagram (Figure 3c). Interestingly, compared with InsP6, bisphosphonate analogue 1 appears more recalcitrant to undergo a conformational change to the 5a1e arrangement at elevated pH.[24b]

Figure 4.

pH-Dependent conformational change of 5PCP-InsP5 (1). a) Schematic illustrating the transition from the 1a5e (1 axial, 5 equatorial) to 5a1e (5 axial, 1 equatorial) conformation at elevated pH. b)–d) DFT optimised geometries for the most stable conformers of L13− (b), HL12− (c), and H2L11− (d). The intramolecular hydrogen bonds are shown as black dotted lines. Phosphoryl groups forming intramolecular hydrogen bonds are in bold. Colour code: C (grey), H (white), O (red), P (orange).

Theoretical investigation of 5PCP-InsP5 protonation and conformation

To understand the conformational preferences of 1 in more detail, the geometries of the predicted protonated species were optimised and their energies were calculated by using a RB3LYP/3-21+G* method (Figures 4 and S4). The fully deprotonated species L13− tends to adopt the 5a1e conformation, because in this arrangement the highly negatively charged phosphate groups are separated best (high XP–P values, Table S4).[27] As discussed in the previous section, protonation of L13− triggers a conformational change, so that the HL12− species adopts the 1a5e form. The 1a5e conformation is stabilised by strong intramolecular hydrogen bonds, which cause only a small distortion of the inositol ring (Table S4). The calculated structures suggest that two intramolecular hydrogen bonds are important for stabilising the 1a5e conformation of HL12− (Figure 4c); one hydrogen bond can form between P1 and P2 (1.22 Å), another one between P4 and P5β (1.33 Å). Comparison of the theoretical data to that obtained for InsP6 further illustrates that the presence of the β-phosphoryl group has a significant effect on both the protonation sequence and conformation of the molecule. For InsP6, the transition from the 5a1e to 1a5e conformation occurred during the HL11− to H2L10− protonation.[24b] This transition was observed experimentally, and theoretical analysis of the energy difference between the two conformers was fully consistent with the experimental results (Figure S5). Analogous calculations for 1 revealed that the molecule only adopts the 5a1e conformation in its fully deprotonated state. Addition of the first proton triggers the conformational change, and the resulting HL12− species is stabilised through intramolecular hydrogen bonds, including a unique hydrogen bond between P4 and P5β (Figure 4c).

Coordination of potassium ions by 5PCP-InsP5 strongly influences inositol conformation

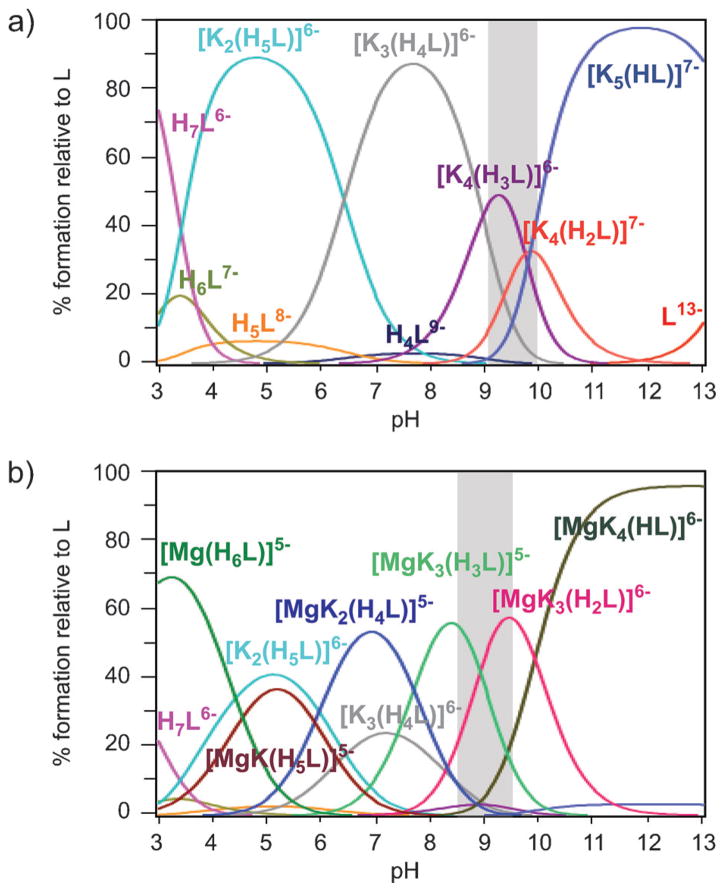

The characterisation of the speciation of 1 in a non-interacting environment provided important structural information, such as the stabilisation of the 1a5e conformation through intramolecular hydrogen bonds. In a cellular environment, however, numerous counter ions for the negatively charged inositol pyrophosphates exist, and the presence of these counter ions will have an impact on their structures and properties. We therefore repeated the 31P NMR titrations in the presence of 150 mM KCl (a concentration close to physiological potassium levels) over a pH range of 3.0 to 13.0. The titration curves immediately indicated a significant interaction between 1 and the potassium ions: Most 31P NMR signals were shifted downfield, due to a deshielding effect upon potassium complexation (Figure S6). Mathematical analysis of the titration curves using HypNMR provided an excellent fit to the experimental data (Figure S6). Five K+ complexes were detected and their species distribution is shown in Figure 5a. All the potassium complexes were remarkably stable (Table S2), considering the low ionic potential of potassium ions. Evidently, the high negative charge of deprotonated 1 must contribute to the stability of the potassium complexes.

Figure 5.

Species distribution diagrams of 5PCP-InsP5 (1) in the presence of potassium and magnesium ions. a) [1] =1.0 mm, [K+]=150 mM.

b) [1] =1.0 mM, [K+]=150 mm, [Mg2+]=1.0 mm. T =22.08C. The pH range of the ligand conformational change is highlighted in grey.

The coordination and protonation sequence for the K+-containing species can be elucidated by examining the calculated individual chemical shifts and their variation with protonation (ΔδP) and/or complexation (ΔδC, Table S3, and the Supporting Information). Whereas protonation has a shielding effect, complexation of potassium ions tends to shift the 31P resonances downfield.[24b] The protonation and complexation processes therefore become distinguishable. A comprehensive picture of the predicted microspecies, and a description of the assignments is provided in the Supporting Information (Figure S7). A pronounced transition occurs when [K4(H2L)]7− is protonated to yield [K4(H3L)]6−: all the 31P NMR signals are shifted significantly (Table S3), revealing a pH-dependent conformational change of the ligand. This conformational change is further confirmed experimentally by the broadening of the 31P NMR signals between pH 9.0 and 10.0, a pH range in which complexes [K4(H2L)]7− and [K4(H3L)]6− co-exist (Figure 5a). Moreover, the formation constant for [K4(H3L)]6− is higher than expected when compared with the other equilibrium constants for successive protonation (Table S2). The greater stability of [K4(H3L)]6− is likely caused by the accompanying conformational transition of the ligand.

The geometries of the most abundant potassium complexes were then optimised by using DFT (Figure S8), and their energies were calculated. According to the computational data, the 5a1e conformation provides a structure with negatively charged cavities, which can be filled with potassium cations, thereby alleviating the repulsion between phosphoryl groups with only minor ring distortion. Only when the pH is low enough will intramolecular H-bonds form to bring the phosphate groups into closer proximity and stabilise the 1a5e conformation. Furthermore, calculation of the energy difference between the two conformations for the [K4(H2L)]7− versus the [K4(H3L)]6− species fully supports the experimentally observed conformational flip (Figure S8 f).

Overall, the strong metal-coordination properties of 1 caused a stark decrease in the pH range for the conformational change of the ligand, in this case provoked by a physiological concentration of potassium ions (compare Figures 3c and 5a).

Magnesium ions further stabilise the 5a1e conformation

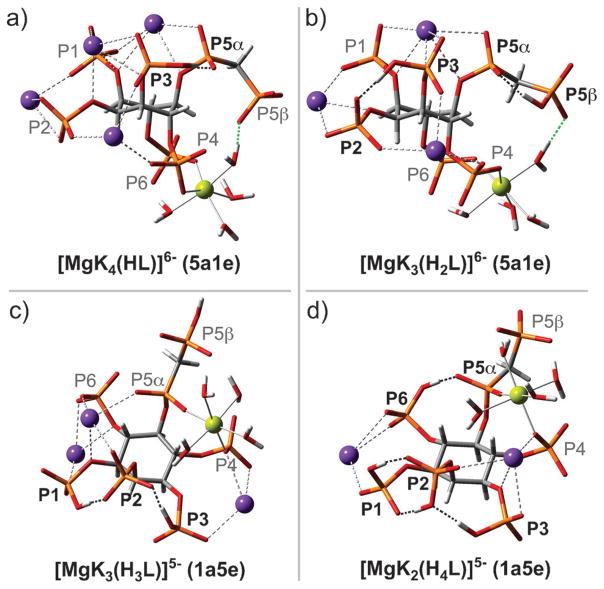

Magnesium is the most abundant divalent cation in cells and it has a propensity for forming strong coordination complexes with phosphate-containing biomolecules, such as ATP and InsP6.[28] We repeated the 31P NMR titration, now in a solution containing 1 mM 1, 150 mM KCl, and 1 mM MgCl2, to provide a cellular concentration of free magnesium cations, and to conduct the titration at a 1:1 stoichiometry of inositol pyrophosphate analogue to magnesium ion (Figure S9). Analysis of these titration curves with HypNMR enabled us to determine the formation constants associated with the magnesium/potassium complexes of 1 (Table S2). The resulting chemical model provided a good fit to the experimental data (Table S3, Figure S9 and S10) and is comprised of six highly stable 1:1 5PCP-InsP5: Mg complexes, containing different numbers of protons and potassium ions: [MgK4(HL)]6−, [MgK3(H2L)]6−, [MgK3(H3L)]5−, [MgK2(H4L)]5−, [MgK(H5L)]5− and [Mg(H6L)]5− (Figure 5b). The locations of the protons and metal cations in these complexes were determined from the ΔδP and ΔδC values from Table S3 (for detailed procedure see the Supporting Information). Based on the solution thermodynamic data, the DFT optimised geometries for four of these complexes are depicted in Figure 6. The structures are stabilised mainly by a net of hydrogen and coordinative bonds, which counteracts the strong electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged phosphate and bisphosphonate groups.

Figure 6.

DFT optimised geometries for the detected 5PCP-InsP5 species in complex with potassium and magnesium ions. Intramolecular hydrogen bonds are shown as black dotted lines. Two unique hydrogen bonds from P5β to a water molecule in the first coordination sphere of magnesium are highlighted as green dotted lines. Phosphoryl groups forming intramolecular hydrogen bonds are in bold. Colour code: C (grey), H (white), O (red), P (orange), K (violet), Mg (lime green).

The inositol conformational change is operative between pH 8.5 and 9.5, where the [MgK3(H3L)]5− complex is deprotonated to form the [MgK3(H2L)]6− species (Figure 5b). To confirm that PCP analogue 1 indeed captures the behaviour of natural 5PP-InsP5 in solution accurately under the experimental conditions described in this section, the 31P NMR spectra of 5PP-InsP5 were recorded between pH 6.0–12.0. Consistent with our previous results,[16e] the conformational change in the presence of potassium and magnesium ions occurs within the same pH range for the bisphosphonate analogue and the natural molecule, as evidenced by the chemical shifts for P2, P1/3, and P4/6 (Figure S11). Notably, the conformational change of 1 is shifted by about 0.5 pH units towards physiological pH by the presence of one equivalent of magnesium ions. The stabilisation of the 5a1e conformation can, in part, be attributed to the preformed chelating site for magnesium ion between P4 and P6 (Figure 6a, b).

Theoretical investigations support this coordination scheme, in which Mg2+ occupies a binding site between P4 and P6 in the [MgK4(HL)]6− and [MgK3(H2L)]6− complexes. In addition, the bisphosphonate group plays a stabilising role in the 5a1e structures, by forming a hydrogen bond to one of the water molecules in the first coordination sphere of the magnesium ion (Figure 6a, b; green dotted lines). By comparison, the magnesium coordination scheme is different in InsP6,[24b] again illustrating the distinctive features of the added β-phosphoryl group.

At pH 7.2, the average pH in the cytoplasm and the nucleus,[ 29] and in the presence of 150 mM K+ and 1 mM Mg2+, the most abundant species are [MgK2(H4L)]5− (1a5e), [MgK3(H3L)]5− (1a5e) and [K3(H4L)]6− (1a5e), at 50.8, 16.9 and 24.0 %, respectively (Table S5). All of these species require one or two deprotonation steps to undergo the conformational change to the 5a1e state. When the pH is raised to 8.0, a pH that can be encountered in spatially restricted regions of cytosolic alkaline pH,[30, 31] the species abundances change significantly: the predominant species is [MgK3(H3L)]5−, with 49.7% (Table S5), which is separated by a single deprotonation step from the other conformer. In fact, a noticeable amount of 5PCP-InsP5 at pH 8.0 adopts the 5a1e state, as the [MgK3(H2L)]6− complex (6.5%, Table S5). Therefore, provided the appropriate cellular microenvironment, a fraction of 5PCP-InsP5 could exist in the 5a1e conformation.

We next calculated the energy differences between the two conformations for [MgK3(H3L)]5− and [MgK3(H2L)]6−, which were experimentally found to occupy the 1a5e and 5a1e conformations, respectively (Figure 6b,c). Consistent with the NMR titration data, the [MgK3(H2L)]6− complex was most stable in the 5a1e state, whereas the 1a5e conformation constituted the species of lowest energy for the [MgK3(H3L)]5− complex (Figure S12). Additional calculations indicated that the energy required for [MgK3(H3L)]5− to undergo the ring flip to the predominantly axial conformer is less than 10 kcalmol−1. To place that value in context, a comprehensive analysis of pharmaceutically relevant protein–ligand complexes demonstrated that large conformational rearrangements of the ligands (>9 kcal mol−1) can be tolerated without penalising the tightness of binding.[32] Therefore, it appears feasible that the energetic cost for the conformational rearrangement could be compensated for by the selective recognition of the 5a1e PP-InsP-Mg complex by a protein binding partner. The [MgK3(H3L)]5− species, which is quite abundant at physiological pH, may therefore target a unique set of protein binding partners in the 5a1e conformation, given that these proteins contain a binding pocket that is complementary in charge and shape.

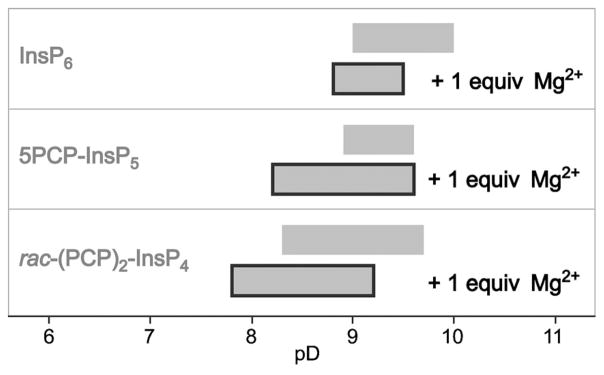

Conformational equilibrium of InsP6, 5PCP-InsP5, and rac- (PCP)2-InsP4 in the presence of cellular metal ion concentrations

Finally, we evaluated the conformational preferences of InsP6, 1, and rac-2 in a solution that contained both sodium and potassium ions (10 mM NaCl, 130 mM KCl), and inositol polyphosphates at a lower concentration (125 μM, compared with 1 mM in the previous experiments). To be able to detect the inositol species at these low concentrations, 1H NMR spectra were recorded, necessitating the use of deuterated solvent. The solutions of InsP6, 1, and rac-2 were titrated from pD 5.0 to 11.5 (Figure S13). All molecules, including rac-2, underwent a conformational change between pD 8.3 and 10.0, as illustrated by the broadening of the signals in this range. We believe that, in addition to the conformational change, chemical exchange between different metal-bound species further contributes to the line broadening over this wide pH range.

One equivalent of MgCl2 (125 μM) was then added to the samples, which shifted the range for the conformational change towards physiological pH in all cases (Figure S13, Figure 7). Given that InsP6 is known to form a complex of higher stoichiometry with Mg2+ (1:5 InsP6:Mg2+),[28b] we wondered whether further addition of Mg2+ would affect the conformational equilibrium of InsP6 and the bisphosphonate analogues. Indeed, addition of 2 or 3 equivalents of Mg2+ to the InsP6 solutions triggered the conformational transition at lower pD (Figure S14). For samples of 1 and rac-2, the addition of 2 or 3 equivalents of Mg2+ also resulted in broadening of the 1H NMR signals at lower pD, between 7.0 and 7.5. The elevated amount of magnesium ions unfortunately caused precipitation of the samples at higher pD, so that the 5a1e conformation for 1 and rac-2 never became visible under these conditions (Figure S15). Overall, the complexation of magnesium ions by the highly phosphorylated inositols facilitated the conformational transition at a lower pH, closer to the physiological environment. While it is tempting to speculate that the inositol pyrophosphates—when in solution at cellular concentrations (1–2 μM), and when surrounded by cellular levels of free magnesium ions (0.5–1.5 mM)—are able to access both conformations with high frequency at physiological pH, this hypothesis can only be tested with more sensitive spectroscopic measurements. These measurements could, for example, rely on incorporating 13C into the inositol ring,[33] or could employ more advanced techniques such as dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP)[34] to lower the limit of detection.

Figure 7.

Effect of magnesium ions on the conformational equilibrium of InsP6, 5PCP-InsP5 (1) and rac-(PCP)2-InsP4 (rac-2). Schematic illustrating a shift of the conformational change of InsP6, 1 and rac-2, towards physiological pD upon addition of magnesium.

Conclusion

We have synthesised and characterised bisphosphonate analogues of the cellular messengers 5PP-InsP5 and 1,5-(PP)2-InsP4. The characterisation included crystallographic studies, which demonstrated high structural overlap between the non-hydrolysable analogues and the diphosphate containing molecules. The methylene group of the bisphosphonate moiety possesses a high degree of flexibility, which enables it to adopt a conformation very similar to that of the diphosphate group.

Analysis of the protonation constants, metal-coordination properties, and conformation of the bisphosphonate analogues illustrated their complex behaviour in solution, and comparison to the properties of InsP6 highlighted the distinctive features of the β-phosphoryl group: In the absence of coordinating counter ions, 5PCP-InsP5 was stabilised in a 1a5e conformation by the formation of strong intramolecular hydrogen bonds, in particular a hydrogen bond between P5β and P4/P6. Introduction of cellular concentrations of potassium and magnesium ions provoked a large shift in the conformational equilibrium and facilitated the transition to the 5a1e conformation at much lower pH. Here, the metal cations coordinate to the preformed cavities between the axial phosphate groups, thereby minimising the electrostatic repulsion in the 5a1e conformation. In addition, theoretical investigations support a unique magnesium binding site in 5PCP-InsP5, in which P4 and P6 directly coordinate to the metal, and P5β binds to a water ligand in the first coordination sphere of the magnesium ion, thereby further stabilising the 5a1e conformation. The speciation diagram of the 5PCP-InsP5-Mg complexes revealed that a small fraction of the inositol pyrophosphate analogue can adopt a 5a1e conformation at pH 8.0, which is a pH that is encountered in alkaline microdomains in the cytoplasm and in the mitochondria. Importantly, theoretical analysis of the species that are more abundant at physiological pH, such as [MgK3(H3L)]5−, suggested that the energy required for promoting a ring flip appears surmountable (<10 kcalmol−1). Therefore, a model in which specific interactions of the PP-InsPmetal complexes with target proteins induce the stabilisation of the 5a1e conformation appears plausible, and some of these interactions may be metal-mediated. The fascinating question then arises whether the PP-InsPs can target different sets of cellular proteins, depending on their metal-complexation and their conformation.

In sum, a picture emerges in which the PP-InsPs can achieve their multifunctional outputs by a variety of mechanisms. Certainly, the spatially and temporally controlled production of these messengers by specific kinases can bestow different signalling properties onto these molecules. Intriguingly though, the PP-InsPs could also control distinct cellular signalling events in response to changes in their protonation, metal complexation, and conformation in the cell. The latter features are not dependent on the action of specific biosynthetic enzymes, but are instead dictated by the intrinsic chemical properties of the PP-InsPs, and the environment and/or the protein binding partners they encounter. Elucidating these added layers of complexity will be essential to understand the regulatory functions of inositol pyrophosphate messengers within cellular signalling networks.

Experimental Section

Experimental details, including full characterization for all compounds, as well as supporting tables and figures, are provided in the Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Istvan Pelczer, Ken Conover, and Dr. Peter Schmieder for guidance with the NMR experiments, and their helpful suggestions. We also thank Laura Wilson from Lotus Separations for assistance with the chiral SFC. Anastasia Hager gratefully acknowledges the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for her postdoctoral fellowship. D.F. received funding from the NIH (DP2 CA186753), the Sidney Kimmel Foundation, the Rita Allen Foundation, and Princeton University.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chem.201601754.

Contributor Information

Prof. Nicolás Veiga, Email: nveiga@fq.edu.uy.

Prof. Dorothea Fiedler, Email: fiedler@fmp-berlin.de.

References

- 1.a) Irvine RF, Schell MJ. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:327–338. doi: 10.1038/35073015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Irvine RF. J Physiol. 2005;566:295–300. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Shears SB. Adv Biol Regul. 2015;57:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wilson MS, Livermore TM, Saiardi A. Biochem J. 2013;452:369–379. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wundenberg T, Mayr GW. Biol Chem. 2012;393:979–998. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Chakraborty A, Kim S, Snyder SH. Science Signal. 2011;4:re1–11. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Barker CJ, Illies C, Gaboardi GC, Berggren PO. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3851–3871. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0115-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Monserrate JP, York JD. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Stephens L, Radenberg T, Thiel U, Vogel G, Khoo KH, Dell A, Jackson TR, Hawkins PT, Mayr GW. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4009–4015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Menniti FS, Miller RN, Putney JW, Shears SB. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3850–3856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Glennon MC, Shears SB. Biochem J. 1993;293:583–590. doi: 10.1042/bj2930583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Saiardi A, Erdjument-Bromage H, Snowman AM, Tempst P, Snyder SH. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1323–1326. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Saiardi A, Nagata E, Luo HR, Snowman AM, Snyder SH. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39179–39185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Schell MJ, Letcher AJ, Brearley CA, Biber J, Murer H, Irvine RF. FEBS Lett. 1999;461:169–172. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01462-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Voglmaier SM, Bembenek ME, Kaplin AI, Dorman G, Olszewski JD, Prestwich GD, Snyder SH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4305–4310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Mulugu S, Bai W, Fridy PC, Bastidas RJ, Otto JC, Dollins DE, Haystead TA, Ribeiro AA, York JD. Science. 2007;316:106–109. doi: 10.1126/science.1139099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Choi JH, Williams J, Cho J, Falck JR, Shears SB. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30763–30775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704655200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lin H, Fridy PC, Ribeiro AA, Choi JH, Barma DK, Vogel G, Falck JR, Shears SB, York JD, Mayr GW. J Biol Chem. 2008;284:1863–1872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805686200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Caffrey JJ, Safrany ST, Yang X, Shears SB. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12730–12736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hua LV, Hidaka K, Pesesse X, Barnes LD, Shears SB. Biochem J. 2003;373:81–89. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kilari RS, Weaver JD, Shears SB, Safrany ST. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:3464–3470. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Horigome C, Ikeda R, Okada T, Takenami K, Mizuta K. Biochemistry. 2009;73:443–446. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Thota SG, Unnikannan CP, Thampatty SR, Manorama R, Bhandari R. Biochem J. 2015;466:105–114. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) York SJ, Armbruster BN, Greenwell P, Peters TD, York JD. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4264–4269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Saiardi A, Resnick AC, Snowman AM, Wendland B, Snyder SH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1911–1914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409322102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee YS, Mulugu S, York JD, O’Shea EK. Science. 2007;316:109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.1139080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao F, Xu J, Fu C, Cha JY, Gadalla MM, Xu R, Barrow JC, Snyder SH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:1773–1778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424642112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Illies C, Gromada J, Fiune R, Leibiger B, Yu J, Juhl K, Yang SN, Barma DK, Falck JR, Saiardi A, Barker CJ, Berggren PO. Science. 2007;318:1299–1302. doi: 10.1126/science.1146824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bhandari R, Juluri KR, Resnick AC, Snyder SH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2349–2353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712227105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chakraborty A, Koldobskiy MA, Bello NT, Maxwell M, Potter JJ, Juluri KR, Maag D, Kim S, Huang AS, Dailey MJ, Saleh M, Snowman AM, Moran TH, Mezey E, Snyder SH. Cell. 2010;140:897–898. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pulloor NK, Nair S, McCaffrey K, Kostic AD, Bist P, Weaver JD, Riley AM, Tyagi R, Uchil PD, York JD, Snyder SH, García-Sastre A, Potter BV, Lin R, Shears SB, Xavier RJ, Krishnan MN. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003981. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Bhandari R, Saiardi A, Ahmadibeni Y, Snowman AM, Resnick AC, Kristiansen TZ, Molina H, Pandey A, Werner JK, Jr, Juluri KR, Xu Y, Prestwich GD, Parang K, Snyder SH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15305–15310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707338104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Azevedo C, Burton A, Ruiz-Mateos E, Marsh M, Saiardi A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21161–21166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909176106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Szijgyarto Z, Garedew A, Azevedo C, Saiardi A. Science. 2011;334:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.1211908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.In analogy to other inositol polyphosphate species: Veiga N, Torres J, Domínguez S, Mederos A, Irvine RF, Díaz A, Kremer C. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:1800–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.06.016.Torres J, Veiga N, Gancheff JS, Domínguez S, Mederos A, Sundberg M, Sánchez A, Castiglioni J, Díaz A, Kremer C. J Mol Struct. 2008;874:77–88.Veiga N, Torres J, Godage HY, Riley AM, Domínguez S, Potter BVL, Díaz A, Kremer C. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009;14:1001–1013. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0510-z.

- 16.a) Isbrandt LR, Oertel RP. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:3144. [Google Scholar]; b) Lindon JC, Baker DJ, Farrant RD, Williams JM. Biochem J. 1986;233:275. doi: 10.1042/bj2330275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Blum-Held C, Bernard P, Spiess B. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3399. doi: 10.1021/ja015616i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Riley AM, Trusselle M, Kuad P, Borkovec M, Cho J, Choi JH, Qian X, Shears SB, Spiess B, Potter BVL. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:1114. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Wu M, Dul BE, Trevisan AJ, Fiedler D. Chem Sci. 2013;4:405–410. doi: 10.1039/C2SC21553E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu M, Chong LS, Capolicchio S, Jessen HJ, Resnick AC, Fiedler D. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:9508–9511;. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2014;126:9662–9665. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott TS, Slowey A, Ye Y, Conway SJ. Med Chem Commun. 2012;3:735–751. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yates LM, Fiedler D. ChemBioChem. 2015;16:415–423. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conway SJ, Gardiner J, Grove SJ, Johns MK, Lim ZY, Painter GF, Robinson DE, Schieber C, Thuring JW, Wong LS, Yin MX, Burgess AW, Catimel B, Hawkins PT, Ktistakis NT, Stephens LR, Holmes AB. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:66–76. doi: 10.1039/b913399b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Wang H, Falck JR, Hall TM, Shears SB. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;8:111–116. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Capolicchio S, Wang H, Thakor DT, Shears SB, Jessen HJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:9508–9511. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2014;126:9662–9665. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Position 5 in 3,5-(PCP)2-InsP4 shows alternative conformations in the solid state (Figure S1).

- 23.Blackburn GM, Kent DE, Kolkmann F. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1981:1188–1190. [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Bebot-Brigaud A, Dange G, Fauconnier N, Gérard C. J Inorg Biochem. 1999;75:71–78. [Google Scholar]; b) Veiga N, Torres J, Macho I, Gomez K, Gonzalez G, Kremer C. Dalton Trans. 2014;43:16238–16251. doi: 10.1039/c4dt01350f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frassineti G, Ghelli S, Gans P, Sabatini A, Moruzzi MS, Vacca A. Anal Biochem. 1995;231:374–382. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The titration was also conducted at 37 °C. The species distribution diagram did not change significantly (Figure S2).

- 27.The calculated energy for the corresponding 1a5e conformer is not much higher, which could explain the persistent broadening of the 31P NMR resonances above pH 11.

- 28.a) Jahnen-Dechent W, Ketteler M. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5:i3–i14. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfr163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Torres J, Domínguez S, Cerdá MF, Obal G, Mederos A, Irvine RF, Díaz A, Kremer C. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2005;99:828–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casey JR, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:50–61. doi: 10.1038/nrm2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.a) Schwiening CJ, Willoughby D. J Physiol. 2002;538:371–382. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ro HA, Carson JH. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37115–37123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bizzarri R, Arcangeli C, Arosio D, Ricci F, Faraci P, Cardarelli F, Beltram F. Biophys J. 2006;90:3300–3314. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.074708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perola E, Charifson PS. J Med Chem. 2004;47:2499–2510. doi: 10.1021/jm030563w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saiardi A, Guillermier C, Loss O, Poczatek JC, Lechene C. Surf Interface Anal. 2014;46:169–172. doi: 10.1002/sia.5659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ni QZ, Daviso E, Can TV, Markhasin E, Jawla SK, Swager TM, Temkin RJ, Herzfeld J, Griffin RG. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:1933–1941. doi: 10.1021/ar300348n. Received: April 14, 2016 Published online on July 27, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.