Summary

Enterococcus faecalis is frequently associated with polymicrobial infections of the urinary tract, indwelling catheters, and surgical wound sites. E. faecalis co-exists with Escherichia coli and other pathogens in wound infections, but mechanisms that govern polymicrobial colonization and pathogenesis are poorly defined. During infection, bacteria must overcome multiple host defenses, including nutrient iron limitation, to persist and cause disease. In this study, we investigated the contribution of E. faecalis to mixed-species infection when iron availability is restricted. We show that E. faecalis significantly augments E. coli biofilm growth and survival in vitro and in vivo by exporting L-ornithine. This metabolic cue facilitates E. coli biosynthesis of the enterobactin siderophore, allowing E. coli growth and biofilm formation in iron-limiting conditions that would otherwise restrict its growth. Thus, E. faecalis modulates its local environment by contributing growth-promoting cues that allow co-infecting organisms to overcome iron limitation and promotes polymicrobial infections.

Keywords: Polymicrobial infection, iron, nutritional immunity, Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, wound infection

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Polymicrobial infections account for approximately 25% of all bacterial infections, the majority of which are biofilm-associated (Magill et al., 2014). Biofilm associated infections have increased antibiotic tolerance and are often chronic in nature, contributing to many of the most prevalent and difficult to treat nosocomial infections. Enterococci are opportunistic pathogens associated with endocarditis, surgical site and other wound infections, urinary tract infection, and catheter-associated urinary tract infection CAUTI (Maki and Tambyah, 2001, Nallapareddy et al., 2006, Nielsen et al., 2013, Dowd et al., 2008). E. faecalis is associated with 11% of all CAUTI, often as part of a polymicrobial community that frequently includes E. coli (Flores-Mireles et al., 2015). Wound infections are often polymicrobial, where Enterococci are associated with more than 5% of surgical site infections and up to 35% of wounds in diabetic individuals (Giacometti et al., 2000, Citron et al., 2007, Dowd et al., 2008).

E. faecalis is nutritionally fastidious and requires environments that provide nutrients that it does not biosynthesize independently (Lebreton et al., 2014). Despite this, E. faecalis is remarkably tolerant of iron limited environments and has been shown to grow in vitro in medium where iron is almost absent; a characteristic of some lactic acid bacteria where manganese serves as a substitute cofactor essential in many cellular enzymes (Bruyneel et al., 1989, Weinberg, 1997, Archibald, 1986). Iron acquisition systems, such as transporters for siderophores or iron from heme-iron sources, have been extensively characterized in E. coli and other bacterial pathogens but have not been functionally characterized in E. faecalis (Miethke and Marahiel, 2007, Neilands, 1993). Metabolic compounds with broad metal chelation specificity have been detected in E. faecalis; however no structural determination or transport characterization for these have as been performed (Lisiecki and Mikucki, 2006, Lisiecki and Mikucki, 2004). Transcriptomic studies highlight putative transport systems with homology to siderophore systems; however roles for these putative systems in iron uptake functionality have not been examined (Vebo et al., 2009, Vebo et al., 2010). The importance of iron for the polymicrobial community, and the ability of E. faecalis to thrive in low-iron environments, suggest that E. faecalis may be successful in polymicrobial interactions when iron is limiting.

In this study, we show that E. faecalis promotes the growth and survival of E. coli biofilm when iron is limited. In a mouse model of wound infection, E. coli CFU are significantly increased during co-infection with E. faecalis compared to single species infections. Using in vitro models of iron restricted growth, we demonstrate that E. faecalis specifically augments E. coli growth and survival in biofilms, and not planktonic growth. E. coli enterobactin siderophore production is necessary for augmented growth during co-infection with E. faecalis. Ornithine exported by E. faecalis serves as a cue to promote E. coli biofilm. This work demonstrates how E. faecalis alters the local environment to promote polymicrobial infections by modulating the amino acid pool available to E. coli and thereby shifting metabolism in favor of siderophore biosynthesis.

Results

E. faecalis promotes the growth of E. coli biofilms under iron limitation

Iron limitation is an effective host innate defense during bacterial infection (Ganz and Nemeth, 2012). We established in vitro assays to mimic this environment for the study of polymicrobial interactions. Using macrocolonies as a surrogate for biofilm formation, we determined the effects of iron limitation on the growth of E. faecalis and E. coli biofilm (Figure 1A,D,E). Growth limitation of E. coli macrocolonies occurred at 0.1mM of the iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl (22D) onwards whereas E. faecalis macrocolony growth remained unaffected at both 0.1mM and 0.7mM 22D and was not visibly affected at concentrations as high as 2.0mM 22D (Figure 1C,F,G), consistent with reports that other lactic acid bacteria can tolerate low iron concentrations (Imbert and Blondeau, 1998, Weinberg, 1997, Bruyneel et al., 1989). We also observed higher E. faecalis tolerance to iron limitation, compared to E. coli, in planktonic culture (Figure S1A,B).

Figure 1. E. faecalis promotes E. coli biofilm growth under iron limitation.

(A–B) E. coli, E. faecalis, Mix(1Ec:1Ef), Mix(1Ec:4Ef) and Mix(1Ec:19Ef) biofilm growth in 22D supplemented TSBG. (C) Supplementation with 50µM FeCl3 restored biomass to iron replete levels. (A–C) Representative macrocolony images at 120hr; scale bars represent 1cm. (D & E) Time course enumeration of E. coli and E. faecalis, respectively, from macrocolonies with single or mixed inoculums under iron limitation. (F) E. coli, E. faecalis and Mix(1Ec:19Ef) biofilm biomass in TSBG supplemented with 22D. Statistical significance was determined by Two-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons, **** P<0.0001. (G) Enumeration of planktonic growth at 120hr for E. coli, E. faecalis and Mix(1Ec:19Ef) in TSBG with 0.1, 0.2 and 0.7mM 22D. (D–G) n = 3 with three technical replicates.

To investigate the effects of iron limitation on mixed species biofilm growth, we grew macrocolonies at varying inoculation ratios, keeping the total number of bacteria in the starting inoculum constant. We observed restricted biomass accumulation for the mixed 1Ec:1Ef macrocolonies at 0.1mM 22D, similar to single species E. coli macrocolonies (Figure 1A). However, increasing the ratio of E. faecalis to E. coli to 1Ec:19Ef gave rise to augmented biomass compared to the 1Ec:1Ef macrocolony and compared to single species macrocolonies (Figure 1B). We therefore focused on the 1Ec:19Ef inoculum ratio for the remainder of our in vitro studies. Addition of ferric chloride to 22D-chelated media restored E. coli macrocolony size to that of the mixed 1Ec:19Ef macrocolony (Figure 1C) and similar to E. coli colonies grown in the absence of 22D (Figure 1A) showing that mixed species biomass augmentation is specific to iron-limitation.

To evaluate growth kinetics, we enumerated the colony forming units (CFU) in colonies at 24, 72 and 120 hours under both iron replete conditions and with 0.1mM and 0.7mM 22D. The presence of E. faecalis resulted in significantly more E. coli in the mixed species macrocolony with 0.1mM 22D at 120hr (Figure 1D). This growth effect was more pronounced at higher chelator concentrations where higher E. coli CFU were observed in mixed species colonies as early as 72hr. In contrast, E. faecalis CFU were similar between both single and mixed species macrocolonies (Figure 1E). Growth of E. faecalis was lower in mixed species macrocolonies at 72hr and 120hr under 0mM or 0.1mM 22D (Fig E), when E. coli is still growing well, suggesting that the differences in E. faecalis growth could be due to nutrient competition arising from robust E. coli growth (Figure 1D).

To determine whether enhanced E. coli growth in the presence of E. faecalis was specific to macrocolonies, we examined planktonic growth as well as a static biofilm assays using polystyrene microtiter plates and quantification via crystal violet as a standard assay for investigation of biofilm formation (O'Toole, 2011). When supplemented with 0.1mM 22D and incubated under the same conditions as that of the macrocolony assays, we observed that biofilm biomass was significantly greater for mixed species biofilms than that of single species biofilm (Figure 1F). E. faecalis mediated enhancement of E. coli growth did not occur in planktonic culture (Figure 1G). Therefore, E. faecalis augmentation of E. coli growth is a biofilm specific phenotype.

A soluble, diffusible E. faecalis factor promotes E. coli biofilm growth

To investigate whether E. faecalis promotes E. coli growth in biofilms in a contact-dependent manner, we inoculated the E. coli and E. faecalis macrocolonies at increasing distances from one another. In this proximity assay, E. coli macrocolonies were larger at closer distances (1cm) to E. faecalis macrocolonies than at greater distances (5cm) (Figure 2A). Increased E. coli colony size correlated with higher E. coli CFU at 120hr (Figure 2B), suggesting that enhanced macrocolony size was dependent on a soluble, diffusible factor that required 120hr to reach E. coli and the for the growth phenotype to become apparent.

Figure 2. E. faecalis proximity causes growth and transcriptome changes in E. coli.

(A) Proximity assay of E. coli and E. faecalis (120hr) macrocolonies respectively in TSBG supplemented with 22D, inoculated from 1cm (proximal) to 5cm (distal). Scale bar represents 1cm. Black brackets indicate proximal and distal sample sites. (B) Enumeration at 24hr and 120hr for E. coli and E. faecalis at both proximal and distal sites, n = 3 with three technical replicates. (C) Statistical enrichment analysis of statistically significant E. coli pathways within top 100 & 500 differentially regulated genes (Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P<0.05). KEGGid: pathway identifier used by KEGG; adjP: Benjamini- Hochberg corrected P-value; Ngenes: number of upregulated genes that are member of the pathway; EF: enrichment factor, the quotient of the observed proportion of pathway annotated genes to the expected proportion under the null hypothesis of no association. (D,E,F) Transcriptional gene expression profiling of E. coli in proximity to E. faecalis. Differentially regulated genes and functional categories (≥2-fold change, FDR<0.05) for (C) E. coli, (E) for E. coli iron related systems, and (F) for E. faecalis when grown in close proximity to E. coli. The black bar indicates the median value for each functional category; each circle represents one gene with red color indicating a functional category where the median value represents decreased expression, and green indicating increased expression; n = 3 biological replicates.

E. faecalis proximity promotes differential E. coli gene expression

To interrogate the mechanism governing E. faecalis-mediated growth promotion of E. coli under iron limitation, we surveyed the transcriptomes of both E. coli and E. faecalis macrocolonies in the proximity assay using RNA-Seq (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). We predicted that the transcriptome of E. coli would be significantly different between the proximal and distal colonies due to differences in growth and physiology. In contrast, since E. faecalis CFU at proximal and distal sites were unchanged, we predicted only modest differences in the transcriptome between the two colony locations. We further hypothesized that additional changes in E. coli mRNA levels would be specifically related to E. faecalis-mediated enhanced growth under the iron limited conditions of the proximity assay. Consistent with our predictions, only 5% (122 genes) of E. faecalis genes were differentially regulated (≥2-fold change, FDR<0.05) when grown close to E. coli, whereas 51% (2617 genes) of E. coli genes were significantly changed in their expression levels when in close proximity to E. faecalis. We then determined whether genes that are members of known biochemical pathways, as defined by KEGG (Kanehisa et al., 2010, Kanehisa et al., 2014), were present in the set of E. coli genes showing higher overall expression in macrocolonies closer to E. faecalis than compared to those more distal, at a proportion greater than random expectation (see Experimental Procedures). From this statistical enrichment analysis, we observed pathways related to growth and metabolism within the top 100 differentially regulated genes attain statistical significance (Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P<0.05) (Figure 2C, Table S2,3). KEGG classification and manual curation of all differentially regulated genes enabled examination of expression for individual genes within each pathway (Figure 2D). These findings supported that genes related to growth and metabolism constituted the bulk of expression changes and showed that of the 18 E. coli genes increased in expression by LogFC≥5.0 between the distal and proximal E. coli sites, 7 were members of the biosynthesis of siderophore group non-ribosomal peptides pathway (KO01053) specifically functioning in yersiniabactin biosynthesis (Figure 2E). Genes encoding components of the membrane transport and biosynthesis systems for the enterobactin (fepABD, entABDEF and fes) and salmochelin (iroEN) siderophores displayed increased expression with log fold-change values ranging from 1 to 3. The salmochelin glucosyltransferase iroB was notably the only siderophore associated gene downregulated at LogFC −1.39. Of the two ferrous iron uptake systems (FeoAB and EfeUOB) only efeUOB displayed increased expression. All iron storage and assimilation genes identified had increased expression with log fold-change values ranging from 1 to 2. Of the 6 genes detected encoding systems for xenosiderophore uptake, 5 of these were decreased in expression by LogFC≤-1. E. faecalis genes with homology to characterized systems involved in iron utilization were expressed at lower levels in close proximity to E. coli suggesting that these systems in E. faecalis may function in a manner different to that of other characterized bacterial iron acquisition systems since iron is limiting and likely to be further restricted due to the abundance and proximity of E. coli iron scavenging systems (Figure 2F).

E. coli ferrous uptake systems do not contribute to E. faecalis driven E. coli growth promotion

The two E. coli ferrous iron uptake systems, encoded by feoAB and efeUOB, were downregulated and upregulated respectively in proximity to E. faecalis. These systems are both regulated in response to iron availability, and efeUOB can be induced under acidic conditions (Cao et al., 2007). Since E. faecalis is a lactic acid-producing bacterium, we hypothesized that local acidification could affect iron solubility and potentially induce the E. coli efeUOB ferrous iron uptake genes. Overlaying macrocolonies in the proximity assay at 7hr, 48hr and post-72hr with a pH indicator solution demonstrated that local pH changes occur, with E. coli macrocolonies being in the acidic range (approximately pH5.5) at 7hr and 48hr (Figure S1C). To determine the role of the ferrous systems in mediating E. coli growth enhancement, we constructed in-frame deletion mutants of the permease components of each system, feoB and efeU, individually and together. However, these mutants were not attenuated for E. faecalis-enhanced E. coli growth in the proximity assay indicating that E. coli mechanisms responding to E. faecalis proximity do not involve ferrous iron acquisition (Figure S1D).

Enterobactin siderophore production is essential for E. faecalis promotion of E. coli growth

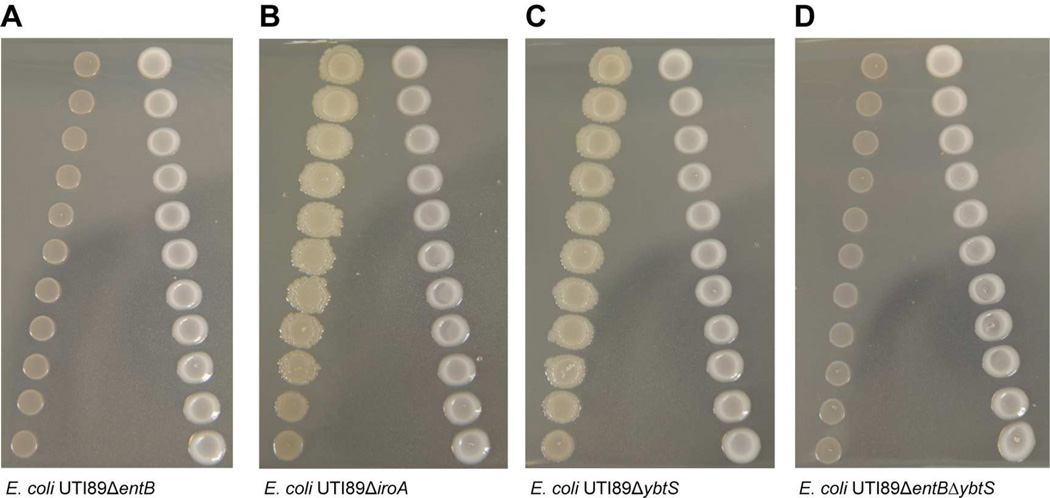

E. coli strain UTI89 used in this study encodes three siderophore biosynthetic operons, responsible for yersiniabactin, enterobactin, and salmochelin which are essential for colonization and virulence in multiple models of infection (Hancock et al., 2008, Wiles et al., 2008, Chaturvedi et al., 2012, Henderson et al., 2009, Lv and Henderson, 2011, Garcia et al., 2011). The siderophore systems in E. coli were more highly transcribed in close proximity to E. faecalis at 120hr, with the virulence associated siderophore yersiniabactin being the most highly expressed. Enterobactin, which is common to most E. coli strains, and its glucosylated derivative salmochelin, were also significantly upregulated (Raymond et al., 2003, Hantke et al., 2003). Using previously characterized mutants for each siderophore alone and in combination (Lv et al., 2014, Henderson et al., 2009), we found that a ΔentB mutant that is unable to produce enterobactin does not exhibit enhanced growth in close proximity to E. faecalis (Figure 3A,D). In contrast, salmochelin and yersiniabactin were dispensable for E. faecalis mediated E. coli growth enhancement (Figure 3B,C). Macrocolony CFU for each of these mutants cultured independently was equivalent to wild type E. coli (Figure S1E). Therefore, enterobactin production specifically, and not that of the other siderophores, was essential for E. faecalis mediated enhancement of E. coli growth under iron limitation.

Figure 3. E. coli enterobactin siderophore mutants do not undergo E. faecalis-mediated growth enhancement.

Proximity assays of 120hr macrocolonies in TSBG supplemented with 22D with E. faecalis and (A) E. coli UTI89ΔentB, (B) E. coli UTI89ΔiroA, (C) E. coli UTI89ΔybtS, and (D) E. coli UTI89ΔentBΔybtS.

Co-infection with E. faecalis augments E. coli virulence in a mouse model of wound infection

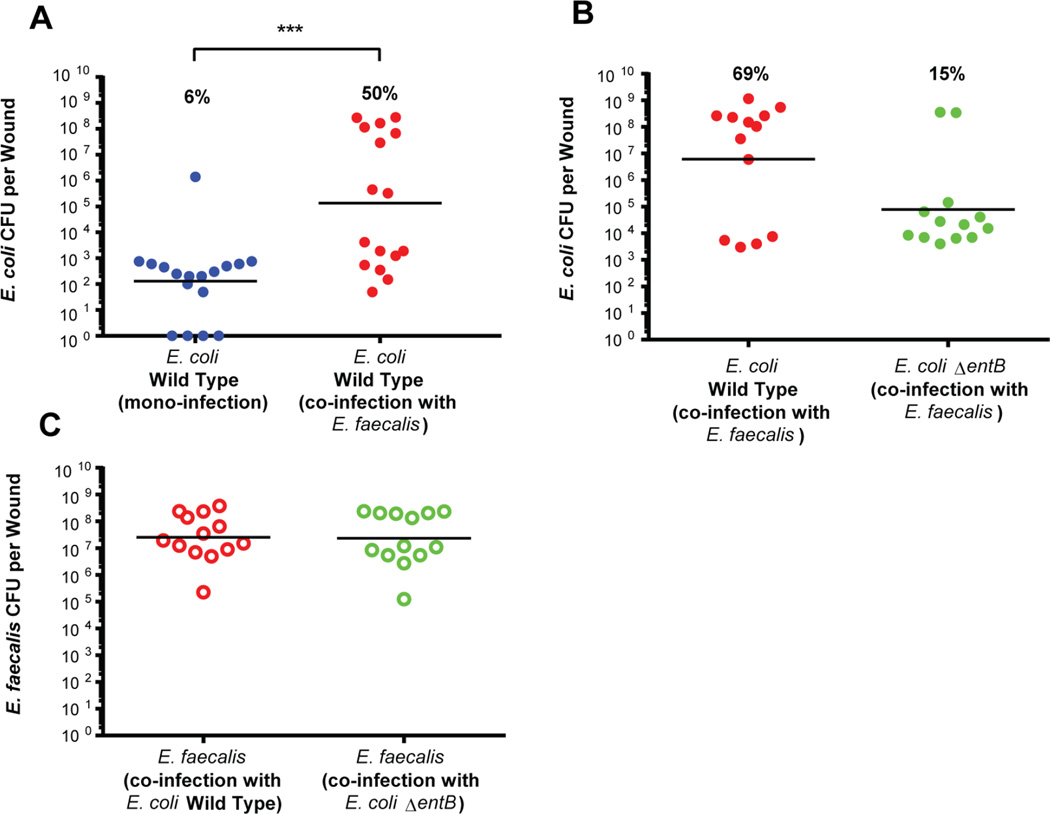

E. faecalis is frequently co-isolated from wound infections with E. coli and other pathogens (Browne et al., 2001, Neut et al., 2011). To evaluate the impact of E. faecalis on E. coli within polymicrobial infections, we used a modified mouse wound excisional model (Dalton et al., 2011), and observed significantly more E. coli CFU from mixed species infections at 24 hours post infection (hpi) than in single species E. coli infections (Figure 4A). This recapitulates in vitro biofilm assay data showing that under iron limitation and when E. coli is present in lower abundance than E. faecalis, E. faecalis can promote the growth of E. coli biofilm (Figure 1B,D,E,F & Figure 2A,B). In comparison, the bacterial burden for E. faecalis from these mixed infections remained constant between single and mixed infections (data not shown). However, when the E. coli enterobactin mutant (ΔentB) was co-infected with E. faecalis in the mouse wound excisional model, the E. coli ΔentB CFU from mixed species infections at 24hpi did not increase to the levels of wild type E. coli co-infected with E. faecalis (Figure 4B). The proportion of mixed species infections giving rise to high titer infections, above 1×105CFU/wound, for E. coli wild type was 50–69% and for E. coli ΔentB was 15% (Figure 4A,B), indicating that the enterobactin mutant was unable to respond to E. faecalis–mediated augmentation in these infections. However, E. coli ΔentB CFU from single infections were comparable to those of single infections with wild type E. coli (data not shown). E. faecalis CFU from wounds co-infected with wild type E. coli and E. coli ΔentB at 24hpi were also the same (Figure 4C). Together, these data demonstrate that the in vitro biofilm assays mimic the in vivo infection environment and have identified conditions that alter infection outcome in vivo.

Figure 4. E. faecalis co-infection increases the growth of E. coli in a mouse model of wound infection.

Mouse wound infection with bacterial burdens determined at 24hpi. The E. coli inoculum in single species controls and/or mixed species infections was 2–4×102CFU/wound for E. coli and 2–4×106CFU/wound. (A) 24hpi E. coli CFU for mono-infected and co-infected wounds. (B) 24hpi E. coli wild type CFU for co-infected compared to E. coli UTI89ΔentB co-infected wounds. (C) E. faecalis CFU at 24hpi from wounds co-infected with E. coli wild type or E. coli UTI89ΔentB. Recovered titers of zero were set to the limit of detection of the assay for statistical analyses and graphical representation in all figures. Horizontal bars represent the median value for each group of mice. N = 3 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by the Mann-Whitney test with Dunn’s post-test for multiple comparisons, *** P=0.0009. Percentages indicate the proportion of data points falling above 1×105CFU/wound for each group.

E. faecalis amino acid flux contributes to E. coli growth promotion

Transcriptional profiling of E. faecalis grown in close proximity to E. coli did not yield insights into the mechanism by which E. faecalis augments E. coli biofilm growth. Therefore, we screened an E. faecalis mariner transposon library (Kristich et al., 2008) for E. faecalis mutants that did not augment mixed species biofilm formation as measured by crystal violet staining (Figure 1F) (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). We hypothesized that we would identify transposon mutants required to produce or export a signal that would ultimately impact enterobactin production in E. coli. We performed a primary screen for transposon mutants that gave rise to a 50% reduction in mixed species biomass in the presence of 0.1mM 22D, representing a defect in augmented growth (Figure S2A). Initial hits from the primary screen were revalidated, and mutants were selected in which mixed species biofilm biomass was significantly lower than that of the wild type mixed species biomass. Table S4 lists the mutants identified following primary validation which can be divided into three classes: 1) transposon insertions in genes previously shown to contribute to E. faecalis single species biofilm formation in iron-replete media (Hancock and Perego, 2004, Nakayama et al., 2006, Pillai et al., 2004, Kristich et al., 2008, Gao et al., 2010, Bourgogne et al., 2006) 2) transposon insertions in genes not reported to be involved in biofilm formation in the above cited studies, and 3) transposon insertions in intergenic regions. We excluded mutants defective for biofilm formation (class 1) from subsequent analyses, reasoning that general biofilm mutants would result in reduced mixed species biofilm due simply to fewer E. faecalis cells present in the assay. However, class 2 mutants were likely to include insertion into E. faecalis genes important for biofilm formation in low iron environments, or into genes involved in signal production or signal exchange with E. coli. To differentiate between these possibilities, and to eliminate any mutants that had general growth defects, we performed single species planktonic and biofilm growth assays of E. faecalis transposon mutants in iron deplete and replete media. Transposon mutants with growth defects in either of these assays were also omitted from subsequent analysis. Table 1 represents the final list of E. faecalis transposon mutants that formed single species biofilms as well as wild type but that did not augment E. coli growth and Figure S2B shows biofilm data for mixed species validation of these mutants. We performed whole genome sequencing to identify the insertion site for each mutant strain.

Table 1.

Final Transposon Mutants Identified through the Library Screen.

| Gene Name | Gene Locus | Description | Genome Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| arcD | OG1RF_10103 | UIT3 family protein, antiporter | 116023 |

| brnQ | OG1RF_10187 | LIVCS family branched chain amino acid cation symporter |

184362 |

| - | OG1RF_10350 | Transcriptional regulator | 362782 |

| - | OG1RF_10620 | ABC superfamily ATP binding cassette transporter, ABC protein |

657774 |

| malL | OG1RF_11138 | Oligo-1,6-glucosidase | 1185608 |

| merR | OG1RF_10308 | MerR family transcriptional regulator |

323110 |

L-ornithine, but not branched chain amino acids, augments E. coli biofilm formation under iron limitation

The transposon library screen identified six genes that did not give rise to augmented mixed species biofilm biomass. We hypothesized that systems involved in signal production or mechanisms of signal exchange to E. coli would be governing the interaction of E. faecalis with E. coli resulting in growth augmentation. ArcD (OG1RF_10103) is the transporter responsible for importing L-arginine and simultaneously exporting L-ornithine as part of the arginine deiminase (ADI) pathway in E. faecalis (Barcelona-Andres et al., 2002). We therefore considered ArcD as a primary candidate since this was the only system facilitating export (L-ornithine) rather than import of a substrate and was therefore a strong candidate for signal exchange. To test this hypothesis, we performed single species E. coli biofilm assays under iron limited conditions and supplemented with L-ornithine in a concentration range up to 3.12mM. We observed significantly increased E. coli biofilm formation at 120hr at concentrations less than 1.5mM L-ornithine (Figure 5A,B). Biofilm growth inhibition occurs at concentrations greater than 1.5mM L-ornithine. In contrast, L-ornithine did not augment biofilm formation by the E. coli enterobactin mutant, suggesting that utilization of L-ornithine was linked to the biosynthesis of the enterobactin siderophore. We analyzed KEGG classification and manual curation data (Figure 2D) to determine if the E. coli uptake system for L-ornithine was differentially expressed when proximal to E. faecalis. The argT hisJQMP ABC transport system increases in expression with LogFC values of 2.521, 1.268 and 1.325 for argT, hisM, and hisQ respectively (Caldara et al., 2006).

Figure 5. L-ornithine Supplementation Enhances E. coli wild type biofilm but not E. coli UTI89ΔentB under iron limitation.

(A–B) E. coli wild type and ΔentB biofilm respectively at 120hr in TSBG supplemented with 22D. L-ornithine supplementation is indicated by the black bar with concentration indicated above. Representative data from three independent experiments is shown, where the trend is consistent among all. Statistical significance of the L-ornithine supplemented samples compared to the non-supplemented E. coli control was determined by Two-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons, * P≤0.05, ** P≤0.01, *** P≤0.001, **** P≤0.0001.

Sequence homology and alignment analysis of the second transporter system (OG1RF_10187) from the transposon library screen predicted that putative substrates for this MFS symporter were branched chain amino acids. Symporters generally function by an inward-directed polarity facilitated by membrane potential; however, in the presence of the substrate on the trans side of the membrane this polarity can be reversed (Pao et al., 1998). We therefore supplemented E. coli biofilm assays with the branched chain amino acids valine, leucine and isoleucine and analyzed biofilm formation at 120hr. We did not observe increased biomass across a concentration range for any of these substrates (Figure S2C).

E. faecalis constitutively produces L-ornithine in biofilm and E. coli siderophore production increases over time

To verify that siderophores and L-ornithine are indeed present within the biofilm, we analyzed proximal and distal macrocolonies from the proximity assay at both 24hr and 120hr in an untargeted metabolomics survey (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). PCA plots were constructed for mass features detected by LC-MS based on proximity (Figure S3A) and time point (Figure S3B), compared to single species macrocolonies. This analysis shows that there are distinct global metabolite profiles between colonies from each species, and between the two sampling times. In addition, we detected the siderophores yersiniabactin (C12038) and vibriobactin (C06769) in all samples but with greater abundance for yersiniabactin at 120hr in the proximity assay (Figure S3C). Vibriobactin is not biosynthesized by E. coli UTI89. However, enterobactin and vibriobactin are both catecholate type siderophores and it is likely that enterobactin has been mis-identified from the KEGG database as vibriobactin. Consistent with RNA expression profiling, yersiniabactin is more abundant at 120hr compared to 24hr. In addition, at 24hr, yersiniabactin is detected in greater abundance within the E. coli samples than the E. faecalis samples, highlighting the capacity for molecular diffusion away from E. coli and into the surrounding environment. Single species controls for E. coli and E. faecalis remain unchanged over time for yersiniabactin. Figure S3C shows the constitutive presence of L-ornithine (C00077) in all of the samples, supporting the model for E. faecalis contribution of L-ornithine flux in the biofilm, and validating the absence of transcriptional expression changes for OG1RF_10103 encoding arcD when in proximity to E. coli. In addition to Lornithine, metabolites central to the arginine biosynthesis pathway including N-acetyl-L-glutamate (C00624), N-acetylornithine (C00437), and L-aspartate (C00049) (Figure 6A) were detected in all samples supporting the role of this pathway in E. faecalis biofilm and signal exchange with E. coli. Overall, this work shows how E. faecalis alters the local environment to drive polymicrobial colonization to infection by overcoming local host nutritional immunity.

Figure 6. Model for E. faecalis Modulation of the Polymicrobial Infection Niche.

(A) Schematic representation of the arginine biosynthesis pathway. Genes encoding the enzymes involved at each step are italicized. Metabolites detected via non-targeted metabolomics are highlighted in green. (B) Model of a polymicrobial infection niche where E. faecalis (blue) modulates E. coli (green) through amino acid flux (ornithine). Siderophore biosynthesis and acquisition are indicated by green arrows. Host iron-bound proteins (from serum and intracellular sources) are highlighted red. The model depicts transition from the initial colonization stage with low E. coli titers to proliferation and infection at higher E. coli titers.

Discussion

Chronic polymicrobial biofilm-associated infections are prevalent in hospital settings and most polymicrobial interactions remain mechanistically uncharacterized. E. coli is frequently co-isolated with E. faecalis from UTI, CAUTI, and wound infections. E. coli is a model organism for extensive functional iron acquisition studies, highlighting the importance of these virulence factors in pathogenicity (Neilands, 1993, Skaar, 2010). Our findings demonstrate that E. faecalis is a major influence on E. coli growth in biofilm when E. coli numbers are initially low and experiencing iron limitation. This phenotype requires cell-to-cell interaction and metabolic cooperation, which are fundamental properties of the bacterial biofilm state, and explain why E. faecalis-mediated growth augmentation is not observed in planktonic culture (Costerton, 1995). Our data support a model of polymicrobial infection in which export of L-ornithine from E. faecalis provides a cue for heightened E. coli enterobactin induction which allows it to overcome iron limitation and growth restriction (Fig 6B). E. coli then proliferates to high titers and increases production of virulence-associated siderophores yersiniabactin and salmochelin to further acquire host-restricted iron sources.

Siderophore biosynthesis and chelation efficiency are important factors influencing the strength of the E. coli response to iron limitation. E. coli UTI89 encodes the catecholate type siderophores enterobactin and salmochelin, and the phenolate type siderophore yersiniabactin (Henderson et al., 2009). The ferric uptake regulator (fur) globally derepresses biosynthesis of siderophore genes upon iron limitation in E. coli (Seo et al., 2014). While E. coli upregulate siderophore genes under iron-limited conditions in the absence of E. faecalis, our data suggest that E. faecalis L-ornithine further stimulates enterobactin biosynthesis independent of fur. Another example of fur-independent transcriptional regulation of a siderophore acquisition system occurs when ferric citrate binds to the outer membrane receptor FecA in E. coli, P. aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumonia and other Gram-negative bacteria. This interaction activates the FecI sigma factor and FecR cytoplasmic membrane transducer to increase expression of the fecABCDE system (Noinaj et al., 2010). Since pH strongly influences chelation efficiency, growth at lower pH ranges and the interaction with the lactic acid bacterium E. faecalis may further influence differential thermodynamic efficiency of iron-siderophore binding (Miethke and Marahiel, 2007). In E. coli Nissle 1917, a strain which produces four siderophores, yersiniabactin biosynthesis functions optimally at neutral to alkaline conditions (Valdebenito et al., 2006). In contrast, catecholate siderophores such as enterobactin optimally chelate iron at neutral pH but are more efficient than carboxylate siderophores above pH5.0 (Miethke and Marahiel, 2007). We propose that early during E. faecalis-E. coli interactions, when iron is limited and E. faecalis may have a growth advantage, E. faecalis lactic acid production favors enterobactin induction in E. coli. During later stages of biofilm development, when the local environment becomes alkaline due to E. coli metabolic byproduct accumulation, a switch to yersiniabactin would make iron chelation efficiency more favorable.

The arginine deaminase system (ADS) is significant for the generation of ATP and ammonia in many bacteria and is important for biofilm formation in Staphylococci (Lindgren et al., 2014). Streptococcus gordonii metabolic exchange of ornithine with the oral pathogen Fusobacterium nucleatum through the antiporter ArcD has been shown to support F. nucleatum biofilm development in mixed species; although, the ornithine-mediated mechanisms that F. nucleatum utilizes have not been elucidated (Sakanaka et al., 2015). A homologous E. faecalis arginine deaminase pathway is encoded by the arcABC genes and the arcD antiporter (Barcelona-Andres et al., 2002). Our work demonstrates that mutation of arcD in E. faecalis disrupts E. coli biofilm growth enhancement under iron limitation, while supplementation of ornithine to single species E. coli biofilm augments growth for wild type in an enterobactin-dependent manner. Ornithine is a precursor component for the biosynthesis of hydroxamate siderophores; however E. coli UTI89 produces only the catecholates enterobactin and salmochelin, and the phenolate yersiniabactin which do not require ornithine as a building block (Yuan et al., 2001). Ornithine is essential within the E. coli arginine biosynthesis pathway which is interconnected with several other biosynthesis and degradative pathways such as pyrimidine and polyamine biosynthesis (Caldara et al., 2006). Metabolomic detection of N-acetyl-L-glutamate (C00624), N-acetylornithine (C00437), and L-aspartate (C00049) in addition to L-ornithine (C00077) confirmed the activity of the arginine biosynthesis pathway. These metabolites are detected in all samples highlighting their importance in cellular metabolism. Differential detection of these by non-targeted LCMS may not be as practical as for the highly biosynthesized siderophores. This pathway is under transcriptional repression control by argR, which in the presence of L-arginine accumulation causes feedback inhibition of the pathway via argA. This feedback inhibition of N-acetylglutamate synthase causes an increase in aromatic amino acid precursors and has been suggested to link to enterobactin siderophore production (Charlier and Glansdorff, 2004), which may explain E. faecalis ornithine driven induction of E. coli siderophore biosynthesis during mixed species biofilms. One component of this pathway, argF, is induced in response to Fe2+-Fur and our data shows decreased transcription of argF when proximal to E. faecalis, supporting the interpretation that E. coli is experiencing iron limitation (Seo et al., 2014). While genes coding for the arginine biosynthesis pathway (argC, argI, argE and argT) and the majority of the E. coli Fur regulon show increased gene expression, the decrease in argF expression may explain a connection between E. coli sensing of environmental iron and ornithine. This finding raises the possibility of ornithine targeting as a means of managing biofilm-associated wound infections which are inherently tolerant to antibiotics and are difficult to resolve.

Wound infections are common, often difficult to eradicate, and managed clinically by a combination of broad-spectrum antibiotics, surgical debridement, or amputation. Our work highlights that the diversity of bacterial species in the infection niche is important and that commensal species can have significant influence on the growth, proliferation, and virulence of other pathogens. The deeper understanding of the mechanisms of polymicrobial interactions within wounds that we demonstrate raises the specter of new approaches for eradicating these recalcitrant, antibiotic-tolerant, biofilmassociated infections.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are listed in Table S1. E. faecalis OG1RF (ATCC47077) (Dunny et al., 1978) was grown in Brain Heart Infusion broth (BHI), E. coli UTI89 (Chen et al., 2006) was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, and both cultured at 37°C under static conditions. MacConkey agar was used for E. coli selection and BHI supplemented with colistin at 10µg/ml and nalidixic acid at 10µg/ml for E. faecalis selection. Overnight cultures were normalized to 2–4×108 CFU/ml in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to OD600nm 0.4 and 0.7 for E. coli and E. faecalis, respectively, prior to dilution for assays described below. For planktonic and biofilm assays, bacteria were cultured at 37°C under 200rpm or static conditions on tryptone soy broth supplemented with 10mM glucose (TSBG) and solidified with 1.5% agar when appropriate (Oxoid Technical No.3). Iron depletion was achieved by supplementation with 2,2'dipyridyl (22D) (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Construction of E. coli UTI89 mutants was performed as described previously (Khetrapal et al., 2015) (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Biofilm Assay

Biofilm microtiter plate assays were performed as previously described (O'Toole, 2011) with minor modifications (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Macrocolonies were produced by inoculating 1–2×106 CFU in a total volume of 5µl onto the surface of TSBG agar and incubating at 37°C. Macrocolonies were excised and resuspended in PBS, followed by CFU enumeration by plating on selective media, RNA extraction and sequencing, or metabolite extraction as described below (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Transposon Library Screen

An E. faecalis OG1RF mariner transposon library was grown in BHI broth at 37°C statically in 2ml deep-well blocks (Greiner Bio-One) using a cryo-replicator (Adolf Kuhner AG) and normalized to an OD600nm of 0.1 (2–4×108CFU/ml) in PBS (Kristich et al., 2008). E. coli stocks were prepared as described above. Mixed species (1Ec:19Ef) inoculums for biofilm assays were prepared by inoculating 8–16×104CFU/200ul with E. coli and with 1.5–3×106CFU/200ul of the normalized transposon mutant cultures. Mutant validation was confirmed by planktonic and biofilm single species assays (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Mouse Model of Wound Infection

Bacterial cultures, prepared as described above, were used to infect wounds in 7-week old female C57BL/6J mice (InVivos Pte. Ltd., Lim Chu Kang, Singapore). Wounds were prepared as previously described (Moreira et al., 2015) with minor modifications (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). All studies and protocols were approved by the Nanyang Technological University Institutional Care and Use Committee (IACUC NTU).

RNA Sequencing

RNA was isolated from macrocolonies using TRIzol reagent (Ambion), cells disrupted using Lysing Matrix D (MP Biomedicals), and nucleic acids purified using chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation. Ribosomal RNA depletion was performed using a RiboZero Magnetic Bacterial kit (Epidemiology; EpiCenter) prior to library preparation for sequencing on an illumina HiSeq2500 instrument.

Metabolite Profiling

Metabolites were extracted from macrocolonies with 10% MeOH, cell and debris was removed by centrifugation, and supernatants containing the metabolites injected to an Acquity UHPLC System (Waters) in-line with LTQ-Orbitrap Velos (Thermofisher) for non-targeted metabolite profiling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation and Ministry of Education Singapore under its Research Centre of Excellence Programme. D.K, W.H.T, Y.Y.H and K.A.K were supported by the National Research Foundation under its Singapore NRF Fellowship programme (NRF-NRFF2011-11), and by the Ministry of Education Singapore under its Tier 2 programme (MOE2014-T2-2-124). S.C. and S.L.C. were supported by NRF-RF2010-10. We thank Daniela Moses and colleagues for performing library preparation and RNA sequencing; Sanjay Swarup, Victor Nesati and colleagues for conducting the metabolomics survey; Jeff Henderson and Scott Hultgren for providing E. coli siderophore mutants; and Kenneth Beckman and colleagues for sequencing of the E. faecalis transposon library.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

D.K. and K.A.K. designed experiments, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript. D.K., W.H.T, and Y.Y.H. performed experiments and analyzed data. J.D. and G.D. provided the transposon library. S.U. and R.B.H.W. analyzed metabolomics data. S.C. generated E. coli mutants. S.L.C. and R.B.H.W. analyzed RNA-seq results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Archibald F. Manganese: its acquisition by and function in the lactic acid bacteria. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1986;13:63–109. doi: 10.3109/10408418609108735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelona-Andres B, Marina A, Rubio V. Gene Structure, Organization, Expression, and Potential Regulatory Mechanisms of Arginine Catabolism in Enterococcus faecalis. Journal of Bacteriology. 2002;184:6289–6300. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.22.6289-6300.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgogne A, Hilsenbeck SG, Dunny GM, Murray BE. Comparison of OG1RF and an isogenic fsrB deletion mutant by transcriptional analysis: the Fsr system of Enterococcus faecalis is more than the activator of gelatinase and serine protease. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:2875–2884. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.8.2875-2884.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne AC, Vearncombe M, Sibbald RG. High bacterial load in asymptomatic diabetic patients with neurotrophic ulcers retards wound healing after application of Dermagraft. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2001;47:44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruyneel B, Vandewoestyne M, Verstraete W. Lactic-Acid Bacteria - Microorganisms able to grow in the absence of available iron and copper. Biotechnology Letters. 1989;11:401–406. [Google Scholar]

- Caldara M, Charlier D, Cunin R. The arginine regulon of Escherichia coli: whole-system transcriptome analysis discovers new genes and provides an integrated view of arginine regulation. Microbiology. 2006;152:3343–3354. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Woodhall MR, Alvarez J, Cartron ML, Andrews SC. EfeUOB (YcdNOB) is a tripartite, acid-induced and CpxAR-regulated, low-pH Fe2+ transporter that is cryptic in Escherichia coli K-12 but functional in E. coli O157:H7. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:857–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier D, Glansdorff N. Biosynthesis of Arginine and Polyamines. Ecosal Plus. 2004;1 doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.3.6.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi KS, Hung CS, Crowley JR, Stapleton AE, Henderson JP. The siderophore yersiniabactin binds copper to protect pathogens during infection. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:731–736. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SL, Hung CS, Xu J, Reigstad CS, Magrini V, Sabo A, Blasiar D, Bieri T, Meyer RR, Ozersky P, Armstrong JR, Fulton RS, Latreille JP, Spieth J, Hooton TM, Mardis ER, Hultgren SJ, Gordon JI. Identification of genes subject to positive selection in uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli: a comparative genomics approach. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:5977–5982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600938103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron DM, Goldstein EJ, Merriam CV, Lipsky BA, Abramson MA. Bacteriology of moderate-to-severe diabetic foot infections and in vitro activity of antimicrobial agents. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2819–2828. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00551-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton JW, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell DE, Korber DR, Lappin-Scott HM. Microbial biofilms. Annual Review of Microbiology. 1995;49:711–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton T, Dowd SE, Wolcott RD, Sun Y, Watters C, Griswold JA, Rumbaugh KP. An in vivo polymicrobial biofilm wound infection model to study interspecies interactions. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd SE, Sun Y, Secor PR, Rhoads DD, Wolcott BM, James GA, Wolcott RD. Survey of bacterial diversity in chronic wounds using pyrosequencing, DGGE, and full ribosome shotgun sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunny GM, Brown BL, Clewell DB. Induced cell aggregation and mating in Streptococcus faecalis: evidence for a bacterial sex pheromone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:3479–3483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz T, Nemeth E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1434–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P, Pinkston KL, Nallapareddy SR, Van Hoof A, Murray BE, Harvey BR. Enterococcus faecalis rnjB is required for pilin gene expression and biofilm formation. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5489–5498. doi: 10.1128/JB.00725-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia EC, Brumbaugh AR, Mobley HL. Redundancy and specificity of Escherichia coli iron acquisition systems during urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1225–1235. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01222-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacometti A, Cirioni O, Schimizzi AM, Del Prete MS, Barchiesi F, D'Errico MM, Petrelli E, Scalise G. Epidemiology and microbiology of surgical wound infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:918–922. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.918-922.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock LE, Perego M. The Enterococcus faecalis fsr two-component system controls biofilm development through production of gelatinase. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5629–5639. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5629-5639.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock V, Ferrieres L, Klemm P. The ferric yersiniabactin uptake receptor FyuA is required for efficient biofilm formation by urinary tract infectious Escherichia coli in human urine. Microbiology. 2008;154:167–175. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/011981-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantke K, Nicholson G, Rabsch W, Winkelmann G. Salmochelins, siderophores of Salmonella enterica and uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains, are recognized by the outer membrane receptor IroN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3677–3682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737682100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson JP, Crowley JR, Pinkner JS, Walker JN, Tsukayama P, Stamm WE, Hooton TM, Hultgren SJ. Quantitative metabolomics reveals an epigenetic blueprint for iron acquisition in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. PLoS pathogens. 2009;5:e1000305. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbert M, Blondeau R. On the iron requirement of lactobacilli grown in chemically defined medium. Curr Microbiol. 1998;37:64–66. doi: 10.1007/s002849900339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Hirakawa M. KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D355–D360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D199–D205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khetrapal V, Mehershahi K, Rafee S, Chen S, Lim CL, Chen SL. A set of powerful negative selection systems for unmodified Enterobacteriaceae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e83. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristich CJ, Nguyen VT, LE T, Barnes AM, Grindle S, Dunny GM. Development and use of an efficient system for random mariner transposon mutagenesis to identify novel genetic determinants of biofilm formation in the core Enterococcus faecalis genome. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:3377–3386. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02665-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebreton F, Willems RJL, Gilmore MS. Enterococcus Diversity, Origins in Nature, and Gut Colonization. In: Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N, editors. Enterococci: From Commensals to Leading Causes of Drug Resistant Infection. Boston: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren JK, Thomas VC, Olson ME, Chaudhari SS, Nuxoll AS, Schaeffer CR, Lindgren KE, Jones J, Zimmerman MC, Dunman PM, Bayles KW, Fey PD. Arginine deiminase in Staphylococcus epidermidis functions to augment biofilm maturation through pH homeostasis. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:2277–2289. doi: 10.1128/JB.00051-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisiecki P, Mikucki J. Citric acid as a siderophore of enterococci? Med Dosw Mikrobiol. 2004;56:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisiecki P, Mikucki J. Iron supply of enterococci by 2-oxoacids and hydroxyacids. Pol J Microbiol. 2006;55:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H, Henderson JP. Yersinia high pathogenicity island genes modify the Escherichia coli primary metabolome independently of siderophore production. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:5547–5554. doi: 10.1021/pr200756n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H, Hung CS, Henderson JP. Metabolomic analysis of siderophore cheater mutants reveals metabolic costs of expression in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:1397–1404. doi: 10.1021/pr4009749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, Lynfield R, Maloney M, Mcallister-Hollod L, Nadle J, Ray SM, Thompson DL, Wilson LE, Fridkin SK Emerging infections program healthcare-associated, I. & antimicrobial use prevalence survey, T. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1198–1208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki DG, Tambyah PA. Engineering out the risk for infection with urinary catheters. Emerging infectious diseases. 2001;7:342–347. doi: 10.3201/eid0702.010240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miethke M, Marahiel MA. Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:413–451. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00012-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira CF, Cassini-Vieira P, Felipetto da Silva M, Barcelos LS. Sking wound healing model – excisional wound and assessment of lesion area. Bio-protocol. 2015;5(22):e1661. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama J, Chen S, Oyama N, Nishiguchi K, Azab EA, Tanaka E, Kariyama R, Sonomoto K. Revised model for Enterococcus faecalis fsr quorum-sensing system: the small open reading frame fsrD encodes the gelatinase biosynthesis-activating pheromone propeptide corresponding to staphylococcal agrd. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:8321–8326. doi: 10.1128/JB.00865-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Sillanpaa J, Garsin DA, Hook M, Erlandsen SL, Murray BE. Endocarditis and biofilm-associated pili of Enterococcus faecalis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2799–2807. doi: 10.1172/JCI29021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilands JB. Siderophores. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;302:1–3. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neut D, Tijdens-Creusen EJ, Bulstra SK, Van Der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Biofilms in chronic diabetic foot ulcers--a study of 2 cases. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:383–385. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.581265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen HV, Flores-Mireles AL, Kau AL, Kline KA, Pinkner JS, Neiers F, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B, Caparon MG, Hultgren SJ. Pilin and sortase residues critical for endocarditis- and biofilm-associated pilus biogenesis in Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:4484–4495. doi: 10.1128/JB.00451-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noinaj N, Guillier M, Barnard TJ, Buchanan SK. TonB-dependent transporters: regulation, structure, and function. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:43–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole GA. Microtiter dish biofilm formation assay. J Vis Exp. 2011 doi: 10.3791/2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao SS, Paulsen IT, Saier MH., Jr Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1–34. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.1-34.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai SK, Sakoulas G, Eliopoulos GM, Moellering RC, Jr, Murray BE, Inouye RT. Effects of glucose on fsr-mediated biofilm formation in Enterococcus faecalis. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:967–970. doi: 10.1086/423139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond KN, Dertz EA, Kim SS. Enterobactin: an archetype for microbial iron transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3584–3588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630018100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakanaka A, Kuboniwa M, Takeuchi H, Hashino E, Amano A. Arginine-Ornithine Antiporter ArcD Controls Arginine Metabolism and Interspecies Biofilm Development of Streptococcus gordonii. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:21185–21198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.644401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo SW, Kim D, Latif H, O’Brien EJ, Szubin R, Palsson BO. Deciphering Fur transcriptional regulatory network highlights its complex role beyond iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4910. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaar EP. The battle for iron between bacterial pathogens and their vertebrate hosts. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000949. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdebenito M, Crumbliss AL, Winkelmann G, Hantke K. Environmental factors influence the production of enterobactin, salmochelin, aerobactin, and yersiniabactin in Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917. Int J Med Microbiol. 2006;296:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vebo HC, Snipen L, Nes IF, Brede DA. The transcriptome of the nosocomial pathogen Enterococcus faecalis V583 reveals adaptive responses to growth in blood. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vebo HC, Solheim M, Snipen L, Nes IF, Brede DA. Comparative genomic analysis of pathogenic and probiotic Enterococcus faecalis isolates, and their transcriptional responses to growth in human urine. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg ED. The Lactobacillus anomaly: total iron abstinence. Perspect Biol Med. 1997;40:578–583. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1997.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles TJ, Kulesus RR, Mulvey MA. Origins and virulence mechanisms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Exp Mol Pathol. 2008;85:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan WM, Gentil GD, Budde AD, Leong SA. Characterization of the Ustilago maydis sid2 gene, encoding a multidomain peptide synthetase in the ferrichrome biosynthetic gene cluster. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4040–4051. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.4040-4051.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.