Abstract

The aim of this work is to evaluate the activity of R(+) limonene of against Anisakidae larvae. Its effectiveness was tested in vitro. The results obtained showed a significant activity of the compound against Anisakis larvae, suggesting further investigation on its potential use in the industrial marinating process. In this regard, the use of R(+) limonene in seafood products could be interesting, also due the sensory attributes resulting from its use and its relatively safe status.

Key words: Limonene, Anisakis, Natural products, Marinating process

Introduction

R(+) limonene (LMN) is the major aromatic compound in essential oils obtained from oranges, grapefruits, and lemons. It is used as a flavouring agent in perfumes, creams, soaps, household cleaning products as well as in several foods such as fruit beverages and confectionary products (Espina et al., 2011). The addition of LMN as flavouring substances in foods is authorised by the Regulation EC N° 872/2012 (European Commission, 2012). The LMN possess also antioxidant, antimicrobial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic properties (Aggarwal et al., 2002; Hirota et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2004; Sun, 2007; Viuda-Martos et al., 2008). However, it is well known that the LMN often have activity against a variety of parasites including nematodes, but its effect against food parasites such as Anisakis larvae has not yet been reported (Arruda et al., 2009; Kanojiya et al., 2014; Macedo et al., 2010; Urban et al., 2014). Anisakiosis is one of the most important fish-borne zoonotic diseases caused by parasites belonging to Anisakis and Pseudoterranova genera. As well known, the human disease is related to the consumption of raw or almost raw seafood products since several fish and cephalopods, commonly parasite hosts (Chai et al., 2005). Digestive disorders in human may occur as a consequence of accidental ingestion fish products parasitized by third-stage larvae (Audicana et al., 2002; Audicana and Kennedy, 2008). For these reasons, the European Regulation EC No 853/2004 (European Commission, 2004) establishes a freezing treatment at -20°C for 24 h for fishery products to be consumed raw or almost raw as well as marinated and/or salted fishery products, if the processing is insufficient to destroy nematode larvae. Recently, several authors had demonstrated a significant action against the L3 larvae of Anisakis simplex exerted by various natural products, especially the essential oils and their components (Giarratana et al., 2014, 2015; Gomez-Rincon et al., 2014; Hierro et al., 2006; Romero Mdel et al., 2012). In this regard, the use of LMN in seafood products could be interesting, also due the sensory attributes resulting from its use (pleasant smell and like-lemon taste) and its relatively safe status. However, the aim of this work is to evaluate the effect of LMN against Anisakis larvae and its potential use during the anchovy marinating process.

Materials and Methods

The present study was carried out in vitro in order to assess the effectiveness of LMN against Anisakis larvae. The compound was supplied by Sigma Aldrich (Milan, Italy). Several concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1 and 5%) in three different liquid media were tested. For each test were used at least 50 Anisakis larvae sampled from 8 specimens of Lepidopus caudatus harvested within 6 hours from the sampling. Larvae were, previously, microscopically evaluated for viability and to assess that they belong to the Anisakis genus type I. Tests in vitro were done by using the following liquid media: i) a solution 1:1 (vol/vol) of distilled water and vinegar (6% acetic acid), 3% NaCl and 1% citric acid in order to reproduce the solution of marinating used by several producers (Colavita, 2012); ii) seeds oil; iii) physiological solution (0.9% NaCl). Each liquid media was used to prepare four solutions with different LMN concentrations. The addition of LMN was made at 0.1, 0.5, 1 and 5% concentrations. Furthermore, a solution for each liquid media was prepared without the addition LMN, as control. Anisakis larvae were introduced into plate dishes with 20 ml of each solution, maintained at 20°C and checked for the viability at 0, 8, 16, 24, 32, 40 and 48 hours. During the experimental treatments, at each fixed time interval, the viability was microscopically checked according to the criteria of Hirasa and Takemasa (1998) assessing the following score: 3 (viable), 2 (reduction of mobility), 1 (mobility only after stimulation) and 0 (death). Larvae were considered dead, when no mobility was observed under stereoscopic microscope in saline solution (0.9% NaCl). The normalized mean score were then used in order to assess the inactivation rate (IR=percentage viability reduction in a minute, under fixed treatment conditions), according to Giarratana et al. (2012).

Results and Discussion

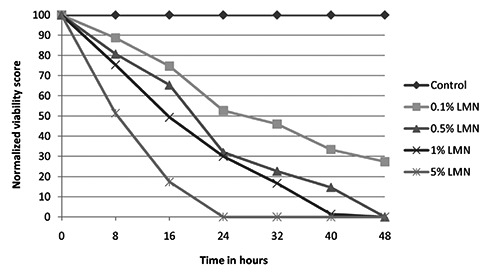

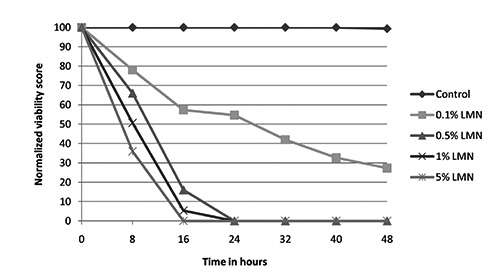

In vitro tests revealed significant activity of LMN against Anisakis larvae. In particular in saline solution, at 5% LMN, a complete inactivation of parasites was observed after 24 hours of treatment, while after 48h at 1% and 0.5% (Figure 1). In marinating solution a complete inactivation of parasites was observed after 16 h and 24 h at 5% and 1% concentrations respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Inactivation rate of larvae in saline solution with 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1 and 5% R(+) limonene.

Figure 2.

Inactivation rate of larvae in marinating solution with 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1 and 5% R(+) limonene.

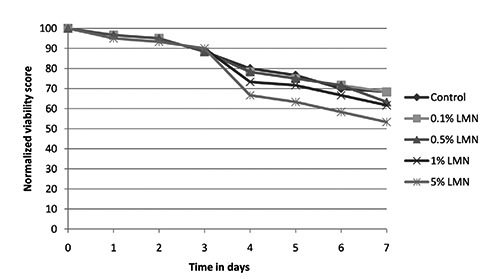

Poor efficacy was detected for larvae treated in seeds oil, where a complete inactivation of parasites was never observed at all concentrations tested after 7 days of treatment (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Inactivation rate of larvae in seeds oil with 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1 and 5% R(+) limonene.

In recent years, the nematocidal activity against Anisakis L3 of several essential oils such as Matricaria chamomilla, Thyme vulgaris and Melaleuca alternifolia, and some of its components has been demonstrated (del Carmen Romero et al., 2012; Giarratana et al., 2014; Navarro et al., 2008; Romero Mdel et al., 2012).

This has an interesting practical implication since marinated seafood products, where the addition of essential oils could represent, according to our results, an alternative method for the inactivation of Anisakidae larvae as well as an innovative method to prevent human anisakiasis. Moreover essential oils and their components possess a relatively safe status and potential functional and technological properties (Bakkali et al., 2008; del Carmen Romero et al., 2012).

Microscopic analysis showed damages of the cuticle and digestive tract of parasites treated in saline and marinating solutions. These results confirm data several authors that linked the effectiveness of natural compounds to the damage caused to cuticle and digestive apparatus of the parasite (del Carmen Romero et al., 2012; Giarratana et al., 2014). In this regard, the lipophilia of these compounds seems play an important role in the cellular damage (Bakkali et al., 2008; Burt, 2004). Observed lesions on larval cuticle and digestive tract could be related to this kind of activity.

Conclusions

This work is the first study concerning in vitro effect of LMN against Anisakis larvae. According to our results LMN showed a remarkable in vitro nematocidal effect at higher concentrations used. The larvicidal activity probably is related to the damage found in the parasite digestive tract. The effectiveness of LMN against Anisakis larvae demonstrated in these experiments justifies further investigations to evaluate the potential use LMN for during industrial marinating process.

References

- Aggarwal KK, Khanuja SPS, Ahmad A, Santha Kumar TR, Gupta VK, Kumar S, 2002. Antimicrobial activity profiles of the two enantiomers of limonene and carvone isolated from the oils of Mentha spicata and Anethum sowa. Flavour Frag J 17:59-63. [Google Scholar]

- Arruda DC, Miguel DC, Yokoyama-Yasunaka JKU, Katzin AM, Uliana SRB, 2009. Inhibitory activity of limonene against Leishmania parasites in vitro and in vivo. Biomed Pharmacother 63:643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audicana MT, Ansotegui IJ, de Corres LF, Kennedy MW, 2002. Anisakis simplex: dangerous—dead and alive? Trends Parasitol 18:20-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audicana MT, Kennedy MW, 2008. Anisakis simplex: from obscure infectious worm to inducer of immune hypersensitivity. Clinical Microb Rev 21:360-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkali F, Averbeck S, Averbeck D, Idaomar M, 2008. Biological effects of essential oils: a review. Food Chem Toxicol 46:446-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt S, 2004. Essential oils: their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods: a review. Int J Food Microbiol 94:223-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai J-Y, Darwin Murrell K, Lymbery AJ, 2005. Fish-borne parasitic zoonoses: status and issues. Int J Parasitol 35:1233-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colavita G, 2012. Igiene e tecnologie degli alimenti di origine animale. Le Point Vétérinaire, Milan, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- del Carmen Romero M, Valero A, Martín-Sánchez J, Navarro-Moll MC, 2012. Activity of Matricaria chamomilla essential oil against anisakiasis. Phytomedicine 19:520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espina L, Somolinos M, Lorán S, Conchello P, García D, Pagán R, 2011. Chemical composition of commercial citrus fruit essential oils and evaluation of their antimicrobial activity acting alone or in combined processes. Food Control 22:896-902. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, 2004. Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for on the hygiene of foodstuffs, 853/2004/EC. In: Official Journal, L 139/55, 30.4.2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, 2012. Commission implementing Regulation of 1 October 2012 adopting the list of flavouring substances provided for by Regulation (EC) No 2232/96 of the European Parliament and of the Council, introducing it in Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 1334/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 1565/2000 and Commission Decision 1999/217/EC, 872/2012/EC. In: Official Journal, L 267/1, 2.10.2012. [Google Scholar]

- Giarratana F, Muscolino D, Beninati C, Giuffrida A, Panebianco A, 2014. Activity of Thymus vulgaris essential oil against Anisakis larvae. Exp Parasitol 142:7-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarratana F, Panebianco F, Muscolino D, Beninati C, Ziino G, Giuffrida A, 2015. Effect of allyl isothiocyanate against Anisakis larvae during the anchovy marinating process. J Food Protect 78:767-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Rincon C, Langa E, Murillo P, Valero MS, Berzosa C, Lopez V, 2014. Activity of tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) essential oil against L3 larvae of Anisakis simplex. BioMed Res Int 2014:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hierro I, Valero A, Navarro MC, 2006. In vivo larvicidal activity of monoterpenic derivatives from aromatic plants against L3 larvae of Anisakis simplex s.l. Phytomedicine 13:527-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasa K, Takemasa M, 1998. Spice science and technology. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota R, Roger NN, Nakamura H, Song H-S, Sawamura M, Suganuma N, 2010. Anti-inflammatory effects of limonene from yuzu (Citrus junos Tanaka) essential oil on eosinophils. J Food Sci 75:H87-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanojiya D, Shanker D, Sudan V, Jaiswal AK, Parashar R, 2014. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of extracts of leaves of Eucalyptus globulus on ovine gastrointestinal nematodes. Parasitol Res 114:141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XG, Zhan LB, Feng BA, Qu MY, Yu LH, Xie JH, 2004. Inhibition of growth and metastasis of human gastric cancer implanted in nude mice by d-limonene. World J Gastroenterol 10:2140-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macedo ITF, Bevilaqua CML, de Oliveira LMB, Camurça-Vasconcelos ALF, Vieira LdS, Oliveira FR, Queiroz-Junior EM, Tomé Ada R, Nascimento NRF, 2010. Anthelmintic effect of Eucalyptus staigeriana essential oil against goat gastrointestinal nematodes. Vet Parasitol 173:93-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro M, Noguera M, Romero M, Montilla M, de Selgas JG, Valero A, 2008. Anisakis simplex sl: Larvicidal activity of various monoterpenic derivatives of natural origin against L 3 larvae in vitro and in vivo. Exp Parasitol 120:295-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero Mdel C, Valero A, Martin-Sanchez J, Navarro-Moll MC, 2012. Activity of Matricaria chamomilla essential oil against anisakiasis. Phytomedicine 19:520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, 2007. D-Limonene: safety and clinical applications. Altern Med Rev 12:259-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban J, Tauchen J, Langrova I, Kokoska L, 2014. In vitro motility inhibition effect of Czech medicinal plant extracts on Chabertia ovina adults. J Anim Plant Sci 21:3293-302. [Google Scholar]

- Viuda-Martos M, Ruiz-Navajas Y, Fernández-López J, Pérez-Álvarez J, 2008. Antifungal activity of lemon (Citrus lemon L.), mandarin (Citrus reticulata L.), grapefruit (Citrus paradisi L.) and orange (Citrus sinensis L.) essential oils. Food Control 19:1130-8. [Google Scholar]