Abstract

The authors tested the effectiveness of a community-based, tribally delivered oral health promotion (OHP) intervention (INT) at reducing caries increment in Navajo children attending Head Start. In a 3-y cluster-randomized trial, we developed an OHP INT with Navajo input that was delivered by trained Navajo lay health workers to children attending 52 Navajo Head Start classrooms (26 INT, 26 usual care [UC]). The INT was designed as a highly personalized set of oral health–focused interactions (5 for children and 4 for parents), along with 4 fluoride varnish applications delivered in Head Start during academic years of 2011 to 2012 and 2012 to 2013. The authors evaluated INT impact on decayed, missing, and filled tooth surfaces (dmfs) increment compared with UC. Other outcomes included caries prevalence and caregiver oral health–related knowledge and behaviors. Modified intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were conducted. The authors enrolled 1,016 caregiver-child dyads. Baseline mean dmfs/caries prevalence equaled 19.9/86.5% for the INT group and 22.8/90.1% for the UC group, respectively. INT adherence was 53% (i.e., ≥3 child OHP events, ≥1 caregiver OHP events, and ≥3 fluoride varnish). After 3 y, dmfs increased in both groups (+12.9 INT vs. +10.8 UC; P = 0.216), as did caries prevalence (86.5% to 96.6% INT vs. 90.1% to 98.2% UC; P = 0.808) in a modified intention-to-treat analysis of 897 caregiver-child dyads receiving 1 y of INT. Caregiver oral health knowledge scores improved in both groups (75.1% to 81.2% INT vs. 73.6% to 79.5% UC; P = 0.369). Caregiver oral health behavior scores improved more rapidly in the INT group versus the UC group (P = 0.006). The dmfs increment was smaller among adherent INT children (+8.9) than among UC children (+10.8; P = 0.028) in a per-protocol analysis. In conclusion, the severity of dental disease in Navajo Head Start children is extreme and difficult to improve. The authors argue that successful approaches to prevention may require even more highly personalized approaches shaped by cultural perspectives and attentive to the social determinants of oral health (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01116739).

Keywords: dental public health, community dentistry, caries, public health dentistry, clinical trial, Native American

Introduction

Caries is the most prevalent chronic disease of childhood, with marked disparities among underserved groups (Vargas et al. 1998; Vargas and Ronzio 2006; Dye et al. 2010; Dye et al. 2015). Children residing in the Navajo Nation have the highest decay prevalence in the world: 86% of Navajo children aged 2 to 5 y have caries (Phipps et al. 2012; Batliner et al. 2014). These children have limited access to dental services and may greatly benefit from receiving oral health promotion (OHP) activities in their communities. The delivery of OHP activities in community settings such as preschool is becoming more common; children may have better access to services in structured school settings, where they spend much of their day. Evidence regarding the effectiveness of this approach in reducing caries is lacking (Tinanoff et al. 2002; Holve 2006; Weintraub et al. 2006; Lawrence et al. 2008; Moyer 2014). Community-based health services delivered by community members have had success in extending health care services in American Indian communities. Our objective was to assess the effect of an OHP program on caries, as delivered in Navajo Nation Head Start by trained Navajo community oral health specialists.

Materials and Methods

Detailed descriptions have been published on the trial design and protocol (Quissell et al. 2014) and caries assessment procedures (Warren et al. 2015). Only salient features of the design and procedures are described here. This trial was approved by the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board; governing bodies at the tribal, agency, and local chapter levels; Navajo departments of Head Start and education; Head Start parent councils; and the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01116739).

Trial Design and Implementation

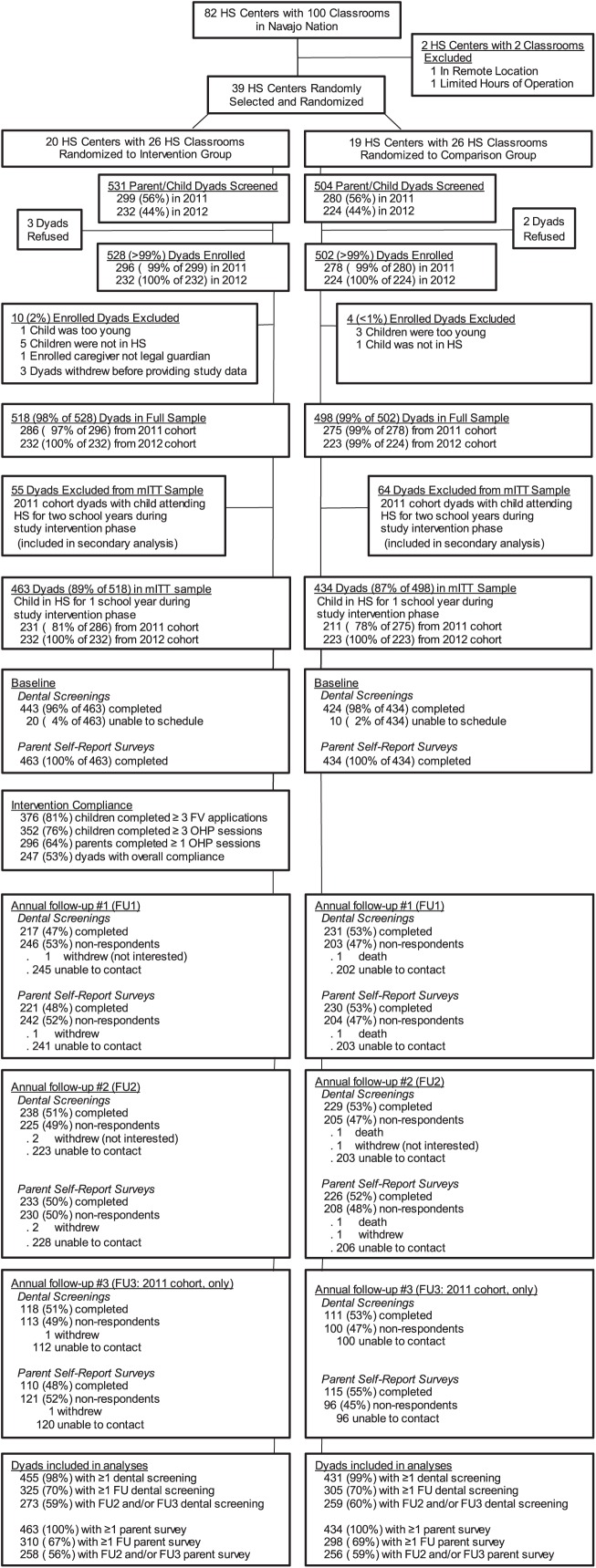

A cluster-randomized design was used, with Navajo Head Start centers as the randomized units. From 82 centers (100 classrooms), 2 centers were excluded due to remoteness and limited hours of operation. The remaining 80 centers were stratified by Navajo Nation agency and classroom/center, randomized to the intervention (INT) or usual care (UC) group and then randomly selected until there were 26 INT and 26 UC classrooms in the trial (Fig.). All caregiver-child dyads in the selected classrooms were screened for trial entry; <1% declined participation or were excluded postenrollment. The final sample comprised 518 INT and 498 UC dyads.

Figure.

CONSORT flow diagram. FU, follow up; FV, fluoride varnish; HS, Head Start; mITT, modified intention to treat; OHP, oral health promotion.

Eligible dyads were Head Start children aged 3 to 5 y and their primary parents/caregivers (henceforth, “caregiver”). Children <3 y of age and caregivers unable to understand English were excluded, as were children with a fluoride varnish (FV) allergy. Written consent/assent was obtained.

Classroom and dyad enrollment occurred in the fall of the 2011 (cohort 1) and fall of 2012 (cohort 2). The INT was administered over the school year from 2011 to 2012 and repeated over the school year from 2012 to 2013. All dyads were exposed to at least 1 y of INT; cohort 1 INT dyads attending Head Start from 2012 to 2013 were eligible for a second year of the repeated INT. Cohort 1 classrooms were evaluated for outcomes each fall from 2011 to 2014 and cohort 2, each fall from 2012 to 2014, providing up to 3 y of follow-up for cohort 1 and up to 2 y of follow-up for cohort 2.

Intervention

The INT comprised 5 child OHP events, 4 caregiver OHP events, and 4 FV applications (3M ESPE VANISH) during each school year. The INT was delivered by 8 trained tribal community members, called community oral health specialists. Each specialist delivered the INT to 3 or 4 classrooms and worked closely with Head Start teachers to coordinate events and communicate with families. Each caregiver OHP event was delivered by 2 specialists, at least 1 of whom spoke Navajo. FV and child OHP events were delivered in the Head Start classroom; caregiver OHP events were delivered at the Head Start center or other convenient location. All INT dyads received toothbrushes and toothpaste for the household at enrollment and data collection events.

Usual Care

UC dyads did not receive INT OHP events or FVs but received toothbrushes and toothpaste at enrollment and data collection events.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures were collected at baseline and annually thereafter for 3 y (years 1 to 3). The trial’s primary outcome measure was decayed, missing, or filled surfaces (dmfs; primary teeth) over time, measured by calibrated dental examiners masked to group assignment (Warren et al. 2015); inspection was visual, without x-rays or probing. Tooth surfaces were counted as decayed when there was frank decay; white spot lesions were not counted as decayed. For teeth missing due to trauma or exfoliation, any prior dmfs measures for that tooth were carried forward; hence, the longitudinal data indicated cumulative disease burden. For teeth crowned or missing due to caries, a score of 4 was given to anterior teeth and 5 to posterior teeth.

Secondary outcome measures included longitudinal assessments of ds and decayed, missing, or filled surfaces (DMFS; permanent dentition) counts, caries prevalence, and validated survey items assessing caregiver oral health knowledge (14 items) and oral health-related behaviors (12 items) on behalf of their children (Wilson et al. 2016). Scores were calculated as percentages of correct answers (knowledge) or appropriate responses (behavior).

Sample Size and Statistical Power

A target sample size of 1,040 caregiver-child dyads was based on the following assumptions: 1) an expected mean dmfs of 23 (SD, 24) without any INT, 2) a 10% reduction of the projected increase in dmfs in the UC group and 40% in the INT group over a 3-y follow-up, 3) an average cluster size of 20 children, 4) an intraclass correlation of 0.045 for dmfs, 5) a power of 80%, 6) a 70% retention rate, and 7) a 2-sided t test (α = 0.05 level).

Statistical Analyses

Most INT and UC dyads included children who attended Head Start for 1 study year. To estimate the effect of 1 y of INT, these dyads were included in the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analysis (Fig.). Dyads in the mITT INT group who received ≥3 child OHP events, ≥1 caregiver OHP event, and ≥3 FVs were categorized as “adherers” in a per-protocol analysis. Dyads with children who attended Head Start for 2 study years (“returnees”) were analyzed separately to estimate the effect of 2 y of INT.

Baseline group characteristics were compared with t tests and chi-square tests, adjusted for clustering. Comparisons of changes in dmfs, ds, and DMFS over time between the mITT INT and UC groups utilized a 3-level overdispersed Poisson model (i.e., Head Start centers, children nested within centers, and repeated measures nested within children) fit to the longitudinal outcomes that included random intercepts for Head Start centers (level 3), random intercepts for children (level 2), and a covariate indicating the natural logarithm of the number of tooth surfaces. The models for dmfs and ds compared outcomes over time from baseline to year 3 follow-up. Because the children did not have permanent teeth at baseline, the model for DMFS compared outcomes from follow-up visits 1 to 3, with baseline dmfs as a covariate. Comparisons of changes in dmfs, ds, and DMFS prevalence over time between the mITT INT and UC groups were similarly performed with a binomial model. Because caregivers sometimes changed over time, we performed the analysis of the oral health knowledge and behavior measures using linear mixed effect models by 2 methods: 1) comparing the mITT INT and UC groups from baseline to year 3 follow-up using all of the caregiver data, with the original caregiver responding in follow-up (yes, no) as a covariate (model 1), and 2) comparing the mITT INT and UC groups from baseline to year 3 follow-up using only data provided by the original caregiver (model 2). For all longitudinal analyses, the primary test of INT effect was based on the group × categorical time interaction.

Parallel secondary analyses compared adherers of the mITT INT group with the UC group (per-protocol analysis) and returnee INT and UC dyads who attended Head Start for 2 y (returnee analysis). Likelihood-based estimation of all models invoked the missing at random assumption, which allowed inclusion of all observed outcome data and accommodated arbitrary patterns of missing data. All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.3.

Results

A total of 897 dyads (463 INT, 434 UC) attended Head Start for 1 study year and were included in the mITT analyses. Their baseline sociodemographic and oral health characteristics are presented in Table 1; 88% of children had early childhood caries (ECC) with a mean dmfs of 21.3.

Table 1.

Baseline Caregiver and Child Characteristics in the Intervention and Usual Care Randomized Groups in the Modified Intention-to-Treat Sample (n = 897).

| Intervention (n = 463) |

Usual Care (n = 434) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | Mean (SE) or % | n | Mean (SE) or % | P Value |

| Caregiver | |||||

| Age, y | 441 | 32.7 (0.5) | 422 | 31.1 (0.5) | 0.036 |

| Female | 463 | 85.1 | 434 | 82.3 | 0.272 |

| Caregiver: mother | 463 | 77.5 | 434 | 76.5 | 0.120 |

| Household incomea | 400 | 4.0 (0.1) | 358 | 4.0 (0.2) | 0.903 |

| Years of education | 462 | 13.7 (0.2) | 429 | 13.5 (0.1) | 0.447 |

| No. children in household | 449 | 3.0 (0.1) | 417 | 2.9 (0.1) | 0.340 |

| Oral health | |||||

| Statusb | 451 | 3.3 (0.1) | 422 | 3.2 (0.1) | 0.811 |

| Knowledge score | 463 | 75.1 (0.8) | 434 | 73.6 (0.6) | 0.145 |

| Behavior score | 463 | 54.4 (1.1) | 434 | 56.1 (0.8) | 0.226 |

| Child | |||||

| Age, y | 463 | 3.7 (0.03) | 432 | 3.7 (0.04) | 0.690 |

| Female | 463 | 51.0 | 434 | 49.1 | 0.536 |

| Oral health statusb | 460 | 2.9 (0.1) | 431 | 3.0 (0.1) | 0.395 |

| Ever had teeth checked by dentist: yes | 460 | 87.8 | 431 | 93.3 | 0.006 |

| Routine dental visit past year: yes | 396 | 88.6 | 394 | 86.5 | 0.407 |

| Dental visit past year for problem: yes | 388 | 53.1 | 393 | 52.4 | 0.858 |

| Dental visits past year for problem, n | 142 | 1.9 (0.1) | 151 | 1.9 (0.1) | 0.868 |

| Fluoride varnish past year: yes | 430 | 81.4 | 399 | 88.0 | 0.138 |

| Times brushed before bedtime past week, n | 450 | 1.8 (0.04) | 428 | 1.9 (0.04) | 0.017 |

| Primary teeth | |||||

| dmfs | 443 | 19.9 (1.0) | 424 | 22.8 (1.2) | 0.049 |

| With any dmfs | 443 | 86.5 | 424 | 90.1 | 0.126 |

| ds | 443 | 5.5 (0.5) | 424 | 6.2 (0.5) | 0.298 |

| With any ds | 443 | 68.4 | 424 | 68.9 | 0.911 |

dmfs, decayed, missing, or filled surfaces (primary dentition); ds, decayed surfaces.

Income measured in levels: 0; 1, <$1,000; 2, $1,000 to $4,999; 3, $5,000 to $9,999; 4, $10,000 to $14,999; 5, $15,000 to $19,999; 6, $20,000 to $29,999; 7, $30,000 to $39,999; 8, $40,000 to $49,999; 9, $50,000 to $74,999; 10, $75,000 to $99,999; 11, ≥$100,000.

Caregiver and child oral health status as reported by caregiver: 1, excellent; 2, very good; 3, good; 4, fair; 5, poor.

Children’s participation in the INT was high: 76.0% attended ≥3 OHP events, and 81.2% received ≥3 FVA. Caregivers’ participation was lower: 63.9% attended ≥1 OHP event (Appendix Table 1).

Mean dmfs increased +3.4, +8.6, and +12.9 surfaces at years 1, 2, and 3 in the INT group, as compared with +4.3, +8.4, and +10.8 surfaces in the UC group (P = 0.216; Table 2), respectively; changes in ds (P = 0.493) and DMFS (P = 0.698) were also similar between the mITT INT and UC groups over time.

Table 2.

Modified Intention-to-Treat Analysis (n = 897): Comparison of dmfs, ds, and DMFS over Time in the Intervention (n = 463) and Usual Care (n = 434) Groups.

| Sample Size, n |

dmfs, Mean (SD) |

ds, Mean (SD) |

DMFS, Mean (SD) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | INT | UC | INT | UC | INT | UC | INT | UC |

| Baseline | 443 | 424 | 19.9 (20.1) | 22.8 (20.1) | 5.5 (7.7) | 6.2 (8.8) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Follow-up | ||||||||

| Year 1 | 217 | 231 | 23.3 (20.4) | 27.1 (21.5) | 3.9 (6.0) | 3.9 (6.4) | 0.03 (0.3) | 0.02 (0.2) |

| Year 2 | 238 | 229 | 28.5 (21.1) | 31.2 (21.3) | 5.0 (7.5) | 5.0 (7.3) | 0.4 (1.2) | 0.4 (1.3) |

| Year 3 | 118 | 111 | 32.8 (22.3) | 33.6 (18.6) | 5.8 (8.3) | 4.8 (6.4) | 1.6 (2.7) | 1.6 (2.6) |

| P valuea | 0.216 | 0.493 | 0.698 | |||||

dmfs, decayed, missing, or filled surfaces (primary dentition); DMFS, decayed, missing, or filled surfaces (permanent dentition); ds, decayed surfaces.

INT, intervention; UC, usual care.

Comparing INT and UC groups over time. For the models for dmfs and ds, we compared outcomes over time from baseline to year 3 follow-up. For the model for DMFS, since the children did not have permanent teeth at baseline, we compared outcomes from years 1 to 3, with baseline dmfs as a covariate.

Caries prevalence (dmfs >0) was very high at baseline in both groups (INT 86.5%, UC 90.1%) and was almost universal by year 3 (INT 96.6%, UC 98.2%; Table 3), with no significant differences over time between INT and UC children for dmfs >0 (P = 0.808), ds >0 (P = 0.591), or DMFS >0 (P = 0.956). At the year 3 follow-up, 39.8% of the INT children and 42.3% of the UC children had permanent tooth caries (DMFS >0).

Table 3.

Modified Intention-to-Treat Analysis (n = 897): Comparison of Children with Caries Experience in the Intervention (n = 463) and Usual Care (n = 434) Groups.

| Sample Size, n |

dmfs >0, % |

ds >0, % |

DMFS >0, % |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | INT | UC | INT | UC | INT | UC | INT | UC |

| Baseline | 443 | 424 | 86.5 | 90.1 | 68.4 | 68.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Follow-up | ||||||||

| Year 1 | 217 | 231 | 89.9 | 90.9 | 57.6 | 54.1 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| Year 2 | 238 | 229 | 95.4 | 96.1 | 62.2 | 65.9 | 14.7 | 16.6 |

| Year 3 | 118 | 111 | 96.6 | 98.2 | 64.4 | 72.1 | 39.8 | 42.3 |

| P valuea | 0.808 | 0.591 | 0.956 | |||||

dmfs, decayed, missing, or filled surfaces (primary dentition); ds, decayed surfaces.

INT, intervention; UC, usual care.

Comparing INT and UC groups over time. For the models for dmfs >0 and ds >0, we compared percentages over time from baseline to year 3 follow-up. For the model for DMFS >0, since the children did not have permanent teeth at baseline, we compared percentages from years 1 to 3, with baseline dmfs >0 as a covariate.

Baseline caregiver oral health knowledge was moderately high in both groups (INT 75.1%, UC 73.6%; Table 4). Mean knowledge score increased by +5.3, +6.3, and +6.1 units at years 1, 2, and 3 follow-up in the INT group and by +3.2, +4.4, and +5.9 units in the UC group (model 1, P = 0.369; model 2, P = 0.099), respectively. Baseline caregiver-reported oral health behavior scores were fairly low in both groups (INT 54.5%, UC 56.1%). The increases in mean oral health behavior scores over time were significantly different between the INT and UC groups (+8.3, +9.0, and +11.2 units at years 1, 2, and 3 vs. +2.1, +5.0, +10.3 in the UC group, respectively; model 1, P = 0.006; model 2, P = 0.003; Table 4) but similar by year 3 (INT 65.6% vs. UC 66.4%; model 1, P = 0.337; model 2, P = 0.136).

Table 4.

Modified Intention-to-Treat Analysis (n = 897): Comparison of Oral Health Knowledge and Behavior of Caregivers over Time in the Intervention (n = 463) and Usual Care (n = 434) Groups.

| Sample Size, n |

Oral Health Knowledge, Mean (SD) |

Oral Health Behavior, Mean (SD) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | INT | UC | INT | UC | INT | UC |

| Baseline | 463 | 434 | 75.1 (13.7) | 73.6 (13.1) | 54.4 (19.3) | 56.1 (18.3) |

| Follow-up | ||||||

| Year 1 | 221 | 230 | 80.4 (13.1) | 76.8 (13.5) | 62.7 (18.8) | 58.2 (19.6) |

| Year 2 | 233 | 225 | 81.4 (14.8) | 78.0 (13.2) | 63.4 (18.7) | 61.1 (18.3) |

| Year 3 | 110 | 115 | 81.2 (13.4) | 79.5 (12.8) | 65.6 (18.9) | 66.4 (17.6) |

| P valuea | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0.369 | 0.006 | ||||

| Model 2 | 0.099 | 0.003 | ||||

INT, intervention; UC, usual care.

Model 1 compares the INT and UC groups for baseline through year 3, with the original caregiver completing the oral health knowledge and behavior questions (yes, no) as a covariate. Model 2 compares the INT and UC groups for baseline through year 3 using the data only when the original caregiver completed the oral health knowledge and behavior questions.

Approximately half of the INT dyads (n = 247, 53.3%) were classified as adherers. The per-protocol analysis comparing the adherer INT group (n = 247) and the UC group (n = 434) indicated that changes in some outcomes over time were different between the 2 groups (Appendix Tables 2–4). Increments in dmfs were slightly smaller in the adherer INT group (+4.6, +7.4, +8.9) when compared with the UC group (+4.3, +8.4, +10.8; P = 0.028); however, ds (P = 0.246) and DMFS (P = 0.428) were similar between the groups over time (Appendix Table 2), as were the caries experience measures for dmfs >0 (P = 0.450), ds >0 (P = 0.397), and DMFS >0 (P = 0.613; Appendix Table 3). Mean oral health knowledge scores increased +7.6, +6.5, and +4.9 at years 1, 2, and 3 in the adherer INT group versus +3.2, +4.4, +5.9 in the UC group (model 1, P = 0.015; model 2, P = 0.007), respectively. Mean oral health behavior scores increased +8.6, +9.8, and +12.3 at years 1, 2, and 3 in the adherer INT group versus +2.1, +5.0, +10.3 in the UC group (model 1, P = 0.007; model 2, P = 0.002), respectively. However, the mean oral health knowledge and behavior scores at year 3 were not significantly different (P > 0.5; Appendix Table 4).

No statistically significant differences between returnees in the INT and UC groups were found (Appendix Tables 5–7).

Discussion

Baseline caries was extremely high for the American Indian children in this cluster-randomized, community-based, tribally delivered OHP trial. Although children’s participation in the INT was high, caregivers’ participation generally was low. In a mITT analysis, we found no difference in dmfs increment in INT children versus UC children; however, children in the adherent group had a smaller dmfs increment across study years. In both analyses, INT caregivers’ oral health knowledge and behaviors increased more rapidly than those of UC caregivers after 1 y, but after 3 y, there were no differences. Nearly all INT and UC children experienced caries by the end of the study. The extreme levels of disease in these American Indian children confirm those reported by others (Grim et al. 1994; Jones et al. 2001; Warren et al. 2012) and emphasize the need for earlier preventive oral health services.

We trained community tribal health workers to deliver the INT in a preschool setting where children spend substantial time. This strategy resulted in high participation by children. Engaging the children’s caregivers was more challenging. Participation in OHP events required travel, and transportation challenges are common in Navajo Nation. Incomes are low; unemployment is high; and personal and community stresses contribute to the challenges faced by Navajo families. Caregivers who participated (≥1 OHP event) in the INT were more likely to have fewer children in the household, external oral health locus of control, and perceptions of more existing barriers to recommended oral health behaviors, as compared with caregivers with poorer participation (Bryant et al. 2016). It is encouraging that both INT and UC caregivers’ oral health knowledge and behaviors improved and that when the INT was received (per-protocol analysis), the dmfs increment was smaller than within the UC group. This suggests that the INT has the potential to favorably influence caregivers’ oral health behaviors and could have a larger clinical impact on populations with greater caregiver participation.

We compared our findings with other ECC prevention studies in Native children. In 2006, Holve reported 35% lower overall caries increments for Navajo children attending Head Start who had at least 4 FVs at previous medical visits, as compared with similar children who had no FV. Also, the caries experience of children who received <4 FVs did not differ from children who received no FV. Children in the Holve study received FV at a much earlier age than did children participating in our study, suggesting that earlier INT may be essential.

Some studies found positive effects of FV when it was initially applied to other Indigenous children with lower severity of dental disease than that of our Navajo population. In a trial with Ojibway-Cree children living in Ontario, Canada, children received Duraflor FV twice a year for 2 y (Lawrence et al. 2008). Compared with controls, children who received the INT had an 18% smaller 2-y mean dmfs increment. In another cluster-randomized clinical trial in an Aboriginal population in Australia, children who received Duraphat FV twice a year and oral health instruction had a 31% lower adjusted dmfs increment than that of control children (Slade et al. 2011). Children participating in both these studies were younger than our population at baseline and had less severe dental disease.

A different approach to ECC prevention in Indigenous children has also been tested. In a cluster-randomized trial testing up to 6 motivational interviewing (MI) sessions with mothers of Cree infants in Quebec, Canada, no difference in enamel caries was found between the INT and control children; however, children of mothers who received at least 4 MI sessions had fewer tooth surface caries, suggesting a dose-response effect for an MI-type INT (Harrison et al. 2012).

Strengths of our study include community participation in INT development and delivery to ensure its cultural relevance (Tiwari et al. 2015). The need to control INT fidelity, along with pragmatic cost considerations, resulted in more rigidly controlled content and INT delivery. The benefit of enrolling families living across a rural and geographically broad setting may have been a barrier when fidelity concerns required caregivers to travel to participate in the INT. These challenges notwithstanding, we successfully completed at least 1 annual follow-up for almost 70% of the original study cohort during the study. Given the extraordinary challenge of preventing caries in a high-risk population with such extreme levels of disease, currently available prevention strategies appear inadequate. Future attempts to control caries in these populations must consider starting earlier, enlisting the participation of caregivers in ways that involve a more individually tailored INT, and restoring active decay. Study limitations include the low rate of caregiver participation, which likely limited response to home care counseling. Also, the fact that nonadherers, who were self-selected, were removed from the INT group was an inherent bias in the per-protocol analyses.

The findings in these aforementioned studies, as well as our new findings, suggest that it is extremely difficult to prevent ECC in vulnerable Indigenous children. The oral health disparities that Indigenous populations experience are complex. Indigenous populations have long been marginalized, and their children, who experience the cumulative stress of growing up in stressful environments, suffer from health inequities. Caulfield et al. (2012) suggested that the teeth of children born to mothers experiencing cumulative toxic stresses have enamel hypoplasia, making them more susceptible to ECC. It is therefore not surprising that ECC was so severe in our population, given the high levels of poverty and unemployment and high levels of interpersonal and community stress that Navajo families experience (all factors that reflect social determinants of health). Experts emphasize the need for research to include approaches that address the complicated social determinants influencing ECC (Sheiham et al. 2011). Certainly, upstream variables such as poverty and stresses increase the challenge of caries prevention among Navajo and other underserved children.

Summary

A community-based, tribally delivered OHP INT for Navajo children enrolled in Head Start resulted in no reduction in caries increments when compared with children in matched classrooms who received the available UC. Although children’s participation was high, caregivers’ participation was difficult to achieve, which suggests that convenience of participation and personal relevance may be important. In spite of this, relatively rapid improvements in caregiver-reported oral health behaviors on behalf of children after 1 y suggested that the INT had some positive impact. Moreover, the caries increment for children whose caregivers attended at least 1 OHP event was smaller when compared with UC children over the 3-y follow-up period. We believe that the early onset of severe dental disease may limit or even eliminate the effectiveness of prevention approaches delivered to children of this age. INTs aimed at preventing ECC need to consider a target population’s unique risks and tailor the INT to those risks. One INT size does not fit all. For Navajo children, prevention efforts must begin very early, occur often, and must address, in a culturally competent way, the more basic upstream impediments to optimal oral health (Watt 2007) as well as their restorative needs.

Author Contributions

P.A. Braun, D.O. Quissell, W.G. Henderson, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; L.L. Bryant, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; S.E. Gregorich, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; C. George and N. Toledo, contributed to data acquisition and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; D. Cudeii, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, critically revised the manuscript; V. Smith, contributed to design, data acquisition, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; N. Johs, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; J. Cheng, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; M. Rasmussen and N.F. Cheng, contributed to acquisition and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; W. Santo, contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; T. Batliner, contributed to conception, design, and data interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; A. Wilson, contributed to conception, design, and data acquisition, critically revised the manuscript; A. Brega, contributed to conception, design, and data interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; R. Roan, contributed to conception, design, and data acquisition, critically revised the manuscript; K. Lind, contributed to design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; T. Tiwari, contributed to data acquisition, critically revised the manuscript; S. Shain, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; G. Schaffer, contributed to conception, design, and data acquisition, critically revised the manuscript; M. Harper, contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; S.M. Manson, contributed to conception and design, critically revised the manuscript; J. Albino, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We acknowledge the leaders of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research–funded Collaborating Centers for Early Childhood Caries (EC4 group). The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

This clinical trial has progressed only with the full support of the Navajo Nation, our field staff, and our community oral health specialists. The authors specifically acknowledge Edwina Kee, health/nutrition coordinator at the Navajo Head Start Central Office, for her tremendous support and guidance as the Head Start liaison. The authors also thank the Navajo Head Start program and all the Head Start center personnel with whom the authors engaged and interacted during this project, including the administrators, teachers, teacher assistants, cooks, bus drivers, and volunteers.

Footnotes

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health (U54DE019259, U54DE019275, and U54DE019285).

A supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://jdr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- Batliner T, Wilson AR, Tiwari T, Glueck D, Henderson W, Thomas J, Braun P, Cudeii D, Quissell D, Albino J. 2014. Oral health status in Navajo Nation Head Start children. J Public Health Dent. 74(4):317–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant LL, Quissell DO, Braun PA, Henderson WG, Johs N, George C, Smith V, Toledo N, Thomas J, Albino JE. 2016. A community-based oral health intervention in Navajo Nation Head Start: participation factors and contextual challenges. J Commun Health. 41(2):340–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caufield PW, Li Y, Bromage TG. 2012. Hypoplasia-associated severe early childhood caries: a proposed definition. J Dent Res. 91(6):544–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye BA, Arevalo O, Vargas CM. 2010. Trends in paediatric dental caries by poverty status in the United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Int J Paediatr Dent. 20(2):132–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla TJ. 2015. Dental caries and sealant prevalence in children and adolescents in the United States, 2011–2012. NCHS data brief. 191:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grim CW, Broderick EB, Jasper B, Phipps KR. 1994. A comparison of dental caries experience in Native American and Caucasian children in Oklahoma. J Public Health Dent. 54(4):220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RL, Veronneau J, Leroux B. 2012. Effectiveness of maternal counseling in reducing caries in Cree children. J Dent Res. 91(11):1032–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holve S. 2006. Fluoride varnish applied at well child care visits can reduce early childhood caries. IHS Primary Care Provider. 31(10):243–245. [Google Scholar]

- Jones C, Phipps K, Reifel N, Skipper B, Blahut P. 2001. The oral health status of American Indian/Alaska Native preschool children: a crisis in Indian country. IHS Primary Care Provider. 26(9):133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence HP, Binguis D, Douglas J, McKeown L, Switzer B, Figueiredo R, Laporte A. 2008. A 2-year community-randomized controlled trial of fluoride varnish to prevent early childhood caries in Aboriginal children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 36(6):503–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. 2014. Prevention of dental caries in children from birth through age 5 years: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 133(6):1102–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps KR, Ricks TL, Manz MC, Blahut P. 2012. Prevalence and severity of dental caries among American Indian and Alaska Native preschool children. J Public Health Dent. 72(3):208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quissell DO, Bryant LL, Braun PA, Cudeii D, Johs N, Smith VL, George C, Henderson WG, Albino J. 2014. Preventing caries in preschoolers: successful initiation of an innovative community-based clinical trial in Navajo Nation Head Start. Contemp Clin Trials. 37(2):242–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheiham A, Alexander D, Cohen L, Marinho V, Moyses S, Petersen PE, Spencer J, Watt RG, Weyant R. 2011. Global oral health inequalities: task group—implementation and delivery of oral health strategies. Adv Dent Res. 23(2):259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade GD, Bailie RS, Roberts-Thomson K, Leach AJ, Raye I, Endean C, Simmons B, Morris P. 2011. Effect of health promotion and fluoride varnish on dental caries among Australian Aboriginal children: results from a community-randomized controlled trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 39(1):29–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinanoff N, Kanellis MJ, Vargas CM. 2002. Current understanding of the epidemiology mechanisms, and prevention of dental caries in preschool children. Pediatric Dentistry. 24(6):543–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari T, Sharma T, Harper M, Zacher T, Roan R, George C, Swyers E, Toledo N, Batliner T, Braun PA, et al. 2015. Community based participatory research to reduce oral health disparities in American Indian children. J Fam Med. 2(3):1028. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas CM, Crall JJ, Schneider DA. 1998. Sociodemographic distribution of pediatric dental caries: NHANES III, 1988–1994. J Am Dent Assoc. 129(9):1229–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas CM, Ronzio CR. 2006. Disparities in early childhood caries. BMC Oral Health. 6 Suppl 1:S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JJ, Kramer KW, Phipps K, Starr D, Dawson DV, Marshall T, Drake D. 2012. Dental caries in a cohort of very young American Indian children. J Public Health Dent. 72(4):265–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JJ, Weber-Gasparoni K, Tinanoff N, Batliner TS, Jue B, Santo W, Garcia RI, Gansky SA; Early Childhood Caries Collaborating Centers. 2015. Examination criteria and calibration procedures for prevention trials of the early childhood caries collaborating centers. J Public Health Dent. 75(4):317–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt RG. 2007. From victim blaming to upstream action: tackling the social determinants of oral health inequalities. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 35(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub JA, Ramos-Gomez F, Jue B, Shain S, Hoover CI, Featherstone JD, Gansky SA. 2006. Fluoride varnish efficacy in preventing early childhood caries. J Dent Res. 85(2):172–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AR, Brega AG, Campagna EJ, Braun PA, Henderson WG, Bryant LL, Batliner TS, Quissell DO, Albino J. 2016. Validation and impact of caregivers’ oral health knowledge and behavior on children’s oral health status. Pediatr Dent. 38(1):47–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.