Abstract

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is an important mediator of hormonal stimulation of cell growth and differentiation through its activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) cascade. Two small G proteins, Ras and Rap1, have been proposed to mediate this activation, with either Ras or Rap1 acting in distinct cell types. Using Hek293 cells, we show that both Ras and Rap1 are required for cAMP signaling to ERKs. The roles of Ras and Rap1 were distinguished by their mechanism of activation, dependence on the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), and the magnitude and kinetics of their effects on ERKs. Ras was required for the early portion of ERK activation by cAMP and was activated independently of PKA. Ras activation required the Ras/Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) PDZ-GEF1. Importantly, this action of PDZ-GEF1 was disrupted by mutation within its putative cyclic nucleotide-binding domain within PDZ-GEF1. Compared with Ras, Rap1 activation of ERKs was of longer duration. Rap1 activation was dependent on PKA and required Src family kinases and the Rap1 exchanger C3G. This is the first report of a mechanism for the cooperative actions of Ras and Rap1 in cAMP activation of ERKs. One physiological role for the sustained activation of ERKs is the transcription and stabilization of a range of transcription factors, including c-FOS. We show that the induction of c-FOS by cAMP required both the early and sustained phases of ERK activation, requiring Ras and Rap1, as well as for each of the Raf isoforms, B-Raf and C-Raf.

Keywords: cyclic AMP (cAMP), extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK), guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), Ras protein, Ras-related protein 1 (Rap1)

Introduction

Hormones that stimulate the synthesis of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) regulate many cell type-specific processes, including gene transcription, cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. These processes are mediated, in part, by the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) or extracellular signal-response kinase (ERK) cascade in a wide range of diverse cell types, including pancreatic islet cells (1, 2), bone cells (3), pituitary cells (4–7), thyroid cells (8, 9), neuronal cells (10–12), and others (13). The duration of ERK activation is a critical component in dictating the cellular response, with sustained ERK activation being associated with cell differentiation in a number of settings (14–18). Specifically, physiological stimuli that trigger a sustained activation of ERKs induce the transcription and stabilization of a range of transcription factors (19).

cAMP directly activates two classes of signaling proteins, the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and cAMP-activated guanine nucleotide exchangers (GEFs).2 Both classes of cAMP-binding proteins have been proposed to mediate cAMP activation of ERKs (20–23). Potential GEFs activated by cAMP include exchange proteins activated by cAMP (Epacs) that are specific for the small G protein Rap1 (24) and PDZ-GEF1, which can activate both Rap1 and the small G protein Ras (25, 26). Using Hek293 cells as a model system, we show that both Ras and Rap1 were required for cAMP activation of ERKs, contributing to the rapid and sustained components of ERK activation, respectively. Ras activation by cAMP was independent of PKA and required the cyclic nucleotide-binding domain within PDZ-GEF1. Rap1 activation required PKA and the Rap1 GEF C3G.

Results

cAMP Activation of ERKs Has Both PKA-dependent and PKA-independent Components

Forskolin, an activator of endogenous adenylate cyclases, mimics the actions of hormones coupled through cAMP (27, 28). Additional elevation of cAMP levels can be achieved through the application of 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), a non-selective phosphodiesterase inhibitor. Stimulation of Hek293 cells by this mixture of forskolin and IBMX (herein referred to as “F/I treatment”) activated ERKs within 2 min, and this activation was sustained for at least 20 min (Fig. 1A). To determine whether this activation was PKA-dependent, we utilized the PKA inhibitor N-(2-(p-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl)-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide (H89). H89 completely blocked cAMP activation of ERKs during the sustained phase of ERK activation (10–20 min), but it only partially blocked the early phase of ERK activation by F/I (2–5 min) (Fig. 1A).

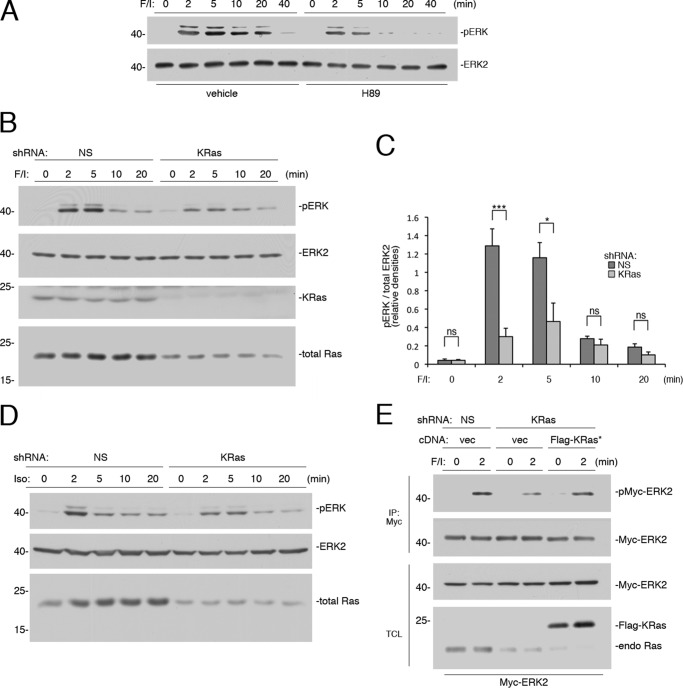

FIGURE 1.

Rapid activation of ERKs by cAMP is PKA-independent and Ras-dependent. A, Hek293 cells were treated with F/I and pretreated with H89 or vehicle, as indicated. Activation of ERK was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures,” using phospho-ERK antibodies. The levels of ERK activation (pERK) and total ERK2 are shown. B, cells transfected with nonspecific (NS) shRNA or shRNA against human KRas were treated with F/I for the times indicated. The levels of pERK and total ERK2 are shown in the 1st two panels. KRas levels are shown in the 3rd panel. Total Ras levels are shown in the 4th panel, using a pan-Ras antibody. C, shRNA data from four independent experiments are shown as bar graphs, with ERK activation (pERK) normalized to total ERK2 levels and the pERK/ERK ratio presented as relative densities. Error bars show standard error. Significance was assessed by unpaired Student's t tests (ns, not significant, * = <0.05, and *** = <0.001). D, cells transfected with NS shRNA or shRNA against human KRas were treated with isoproterenol (Iso) for the times indicated. The levels of pERK, total ERK2, and total Ras (using a pan-Ras Ab) are shown. E, cells were transfected with Myc-ERK2 and either NS shRNA or shRNA against KRas, along with either vector or FLAG-tagged shRNA-resistant wild type KRas (FLAG-KRas*). Cells were treated with F/I for 2 min or left untreated and subjected to immunoprecipitation using agarose-coupled Myc Ab. The levels of Myc-ERK2 activation (pMyc-ERK2) and total Myc-ERK2 within the IP are shown. The levels of Myc-ERK2 and Ras proteins (total Ras) within the total cell lysate (TCL) are shown in the 3rd and 4th panels, respectively. Note that both FLAG-KRas and endogenous Ras are easily separated on this gel, with FLAG-KRas migrating more slowly.

Two small G proteins, Ras and Rap1, have been proposed to mediate cAMP activation of ERKs (20, 22, 29). To determine whether this early phase might be mediated by Ras, we utilized shRNAs to selected Ras isoforms. In Hek293 cells, shRNA against KRas eliminated the majority of the total Ras proteins in Hek293 cells (Fig. 1B), demonstrating that KRas is the predominant Ras isoform in these cells. The major consequence of shRNA knockdown of KRas on ERK activation was the loss of ERK activation at 2 and 5 min. In contrast, the late (10 and 20 min) activation of ERKs was spared (Fig. 1, B and C). Isoproterenol, an agonist of the β (β1 and β2)-adrenergic receptor, also induced a rapid activation of ERK. The initial phase of ERK activation by isoproterenol had a Ras component that was largely mediated by KRas (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, this Ras component was more transient than that seen with F/I, perhaps because endogenous phosphodiesterases were not inhibited by IBMX. The controls to determine the ability of an shRNA-resistant cDNA for KRas to reverse the effects of KRas shRNA on ERK activation by F/I at 2 min are shown (Fig. 1E).

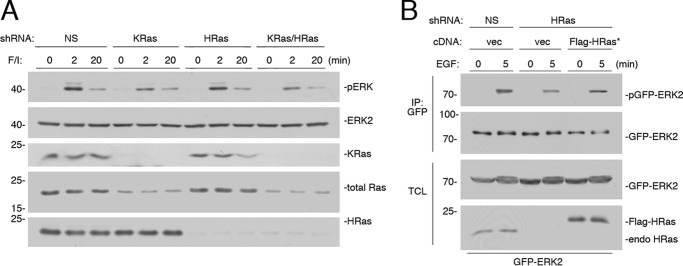

In Hek293 cells, the effect of knockdown of Ras isoforms was similar whether KRas shRNA was used alone or with shRNA against HRas (Fig. 2A), suggesting that HRas has a minor role in cAMP's activation of ERKs. Knockdown of KRas lowered ERK activation at 2 min of F/I treatment, but not at 20 min (Fig. 2A), as seen in Fig. 1B. HRas was also expressed in these cells and was efficiently eliminated by HRas shRNA. However, the effect on total Ras was minimal (Fig. 2A). Accordingly, there was no effect of HRas knockdown on ERK activation at either 2 or 20 min of F/I treatment (Fig. 2A). Because of the lack of effect of HRas shRNA on F/I stimulation of ERKs, the controls to determine the ability of an shRNA-resistant cDNA for HRas to reverse the effect of HRas knockdown used EGF, whose receptor can couple to multiple Ras isoforms, including HRas (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

KRas is the major Ras isoform downstream of cAMP. A, cells transfected with NS shRNA, shRNA against human KRas, shRNA against human HRas, or shRNAs against both KRas and HRas (KRas/HRas) were treated with F/I for the times indicated. The levels of ERK activation (pERK) and total ERK2 are shown in the 1st two panels. The levels of KRas, total Ras, and HRas are shown in the 3rd, 4th, and 5th panels, respectively. B, cells were transfected with GFP-ERK2 and NS shRNA or shRNA against HRas and either vector or FLAG-tagged shRNA-resistant HRas (FLAG-HRas*). Cells were treated with EGF for 5 min or left untreated, lysed, and subjected to GFP IP. The levels of activation of GFP-ERK2 (pGFP-ERK2) and the levels of total GFP-ERK2 are shown in the 1st and 2nd panels, respectively. The levels of GFP-ERK2 and HRas within the TCL are shown in the bottom two panels.

cAMP Activates Ras in a PKA-independent Manner via PDZ-GEF1

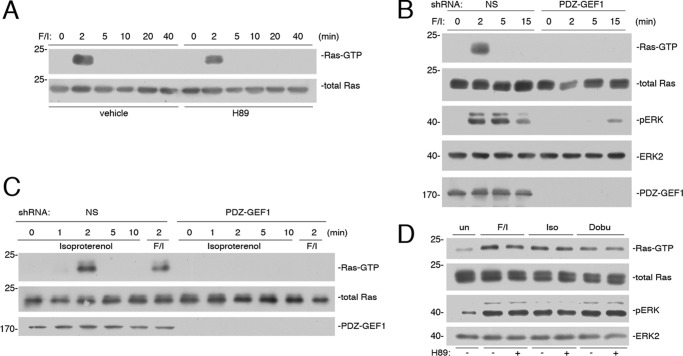

cAMP activation of Ras via F/I was rapid and transient and insensitive to H89, demonstrating that Ras activation by cAMP was PKA-independent (Fig. 3A). PKA-independent activation of small G proteins by cAMP has been well studied for Epacs, whose actions are selective for Rap1 (30). PDZ-GEF1 (also called RapGEF2, RA-GEF1, nRapGEP, and CNrasGEF) (20, 31, 32) is closely related to Epac and can be activated by cAMP (20, 31), but unlike Epacs, PDZ-GEF1 is a potential GEF for Ras (25, 26). Experiments using shRNA against human PDZ-GEF1 eliminated Ras activation by cAMP and reduced ERK activation at early time points (Fig. 3B). Like F/I, isoproterenol activation of Ras was dependent on PDZ-GEF1, as it was blocked by shRNA for PDZ-GEF1 (Fig. 3C). Isoproterenol is an agonist of both β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors. Both receptors are expressed in cardiomyocytes, and their activation has been linked to ERK activation in these cells (33, 34). Isoproterenol and the more selective β1 agonist dobutamine activated Ras and ERKs to similar extents in newborn mouse cardiomyocytes. As in Hek293 cells, these effects were independent of PKA, as they were insensitive to the effects of H89 (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 3.

Ras activation by cAMP is PKA-independent and mediated by PDZ-GEF1. A, Hek293 cells were treated with F/I for the times indicated and pretreated with H89 or vehicle, as indicated. Ras activity (Ras-GTP) was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures” and shown in the 1st panel. Total Ras is shown in the 2nd panel. B, cells transfected with NS shRNA or shRNA against human PDZ-GEF1 were treated with F/I for the times indicated. Ras-GTP was measured as described, shown in the 1st panel. Total Ras is shown in the 2nd panel. The levels of pERK, total ERK2, and PDZ-GEF1 are shown in the bottom three panels, respectively. C, cells were transfected with NS shRNA or PDZ-GEF1 shRNA and treated with F/I or isoproterenol for the times indicated. The levels of Ras-GTP are shown in the 1st panel. Total Ras levels are shown in the 2nd panel, and the efficacy of the knockdown of PDZ-GEF1 is shown in the 3rd panel. D, newborn mouse cardiomyocytes were harvested and treated with F/I, isoproterenol (Iso), or dobutamine (Dobu) for 2 min, or left untreated (un), and either pretreated with H89 (+) or not pretreated (−), as indicated. Ras-GTP was measured in the 1st panel. Total Ras levels are shown in the 2nd panel. pERK and total ERK2 levels are shown in the 3rd and 4th panels, respectively.

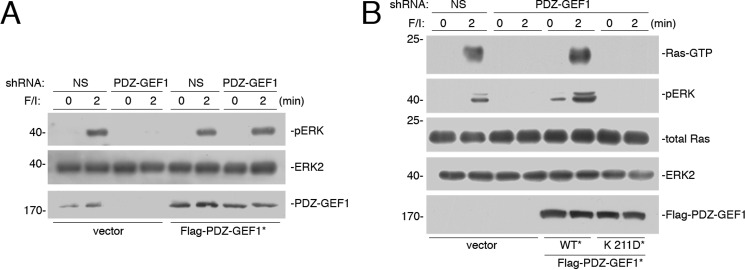

PDZ-GEF1 Activation of Ras and ERKs Requires Its Putative Cyclic Nucleotide-binding Domain

The specificity of shRNA for PDZ-GEF1 was confirmed by showing that transfection of an shRNA-resistant wild type PDZ-GEF1 could rescue the loss of ERK activation (Fig. 4A). Like Epacs, PDZ-GEF1 contains a putative cyclic nucleotide-binding domain (25, 26). Mutation of an essential residue within this domain creates a mutant PDZ-GEF1 K211D that can no longer bind cAMP in vitro (31). An shRNA-resistant version of this mutant could not rescue the loss of Ras and ERK activation (Fig. 4B), suggesting that cAMP binding to the cyclic nucleotide-binding domain of PDZ-GEF1 is required for Ras activation by cAMP and the resultant ERK activation in vivo.

FIGURE 4.

cAMP-binding site within PDZ-GEF1 is required for cAMP activation of Ras. A, Hek293 cells were transfected with NS shRNA or shRNA against PDZ-GEF1 and either vector or FLAG-tagged shRNA-resistant wild type PDZ-GEF1 (WT*). Cells were treated with F/I for the times indicated. The levels of pERK and total ERK2 are shown in the 1st and 2nd panels, respectively. The levels of PDZ-GEF1 are shown in the 3rd panel. B, cells transfected with NS shRNA or shRNA against PDZ-GEF1 and either vector, FLAG-tagged shRNA-resistant wild type PDZ-GEF1 (WT*), or FLAG-tagged shRNA-resistant PDZ-GEF1 K211D mutant (K211D*). Cells were treated with F/I for the times indicated. The levels of Ras-GTP are shown in the 1st panel. The levels of pERK, total Ras, total ERK2, and FLAG-PDZ-GEF1 are shown in the lower four panels, respectively.

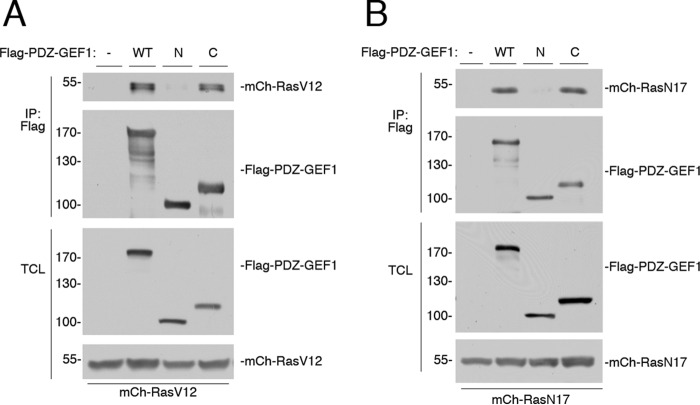

Using co-immunoprecipitation, we show that PDZ-GEF1 associated with Ras. Both N- and C-terminal fragments of PDZ-GEF1 were used to define this binding site further. The N-terminal fragment comprised amino acids 1–716 and contained a potential Ras association (RA) domain located between amino acids 593 and 692. The C-terminal fragment comprised amino acids 693–1499 and contained the catalytic CDC25 homology/GEF domain located between amino acids 712 and 899 (26, 32, 35). We show that binding to RasV12 occurs through the C-terminal catalytic domain, with negligible binding to the N-terminal fragment (Fig. 5A). Similar results were seen with the mutant RasN17 (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that the RA domain contributes negligibly to Ras binding, consistent with previous studies (26, 32, 36).

FIGURE 5.

Ras binds to PDZ-GEF1. A, Hek293 cells were transfected with mCherry-HRasV12 (mCh-RasV12) and either vector (−), FLAG-PDZ-GEF1 (WT), a FLAG-tagged N-terminal fragment of PDZ-GEF1 spanning amino acids 1–716 (N), or a FLAG-tagged C-terminal fragment spanning amino acids 693–1499 (C), and cells were subjected to FLAG IP. The levels of mCh-RasV12 within the IP are shown in the 1st panel. The levels of FLAG-PDZ-GEF1 and fragments within the IP are shown in the 2nd panel. The levels of FLAG-PDZ-GEF1 and fragments within the TCL are shown in the 3rd panel. The levels of mCh-RasV12 within the TCL are shown in the 4th panel. B, cells were transfected with mCherry-HRasN17 (mCh-RasN17) and either vector (−), FLAG-PDZ-GEF1 (WT), the FLAG-tagged N-terminal fragment of PDZ-GEF1 (N), or the FLAG-tagged C-terminal fragment (C), and subjected to FLAG IP. The levels of mCh-RasN17 within the IP are shown in the 1st panel. The levels of FLAG-PDZ-GEF1 and fragments within the IP are shown in the 2nd panel. The levels of FLAG-PDZ-GEF1 and fragments within the TCL are shown in the 3rd panel. The levels of mCh-RasN17 within the TCL are shown in the 4th panel.

It has been reported that Rap1 can bind the RA domain of PDZ-GEF1 (26, 32, 36), although Rap1 binding did not affect its GEF activity (35, 36). An intact RA domain is required for full PDZ-GEF activity in vivo, and a role in subcellular localization has been proposed (36). Taken together, these data suggest that the GEF catalytic site provides the major interaction with Ras.

Sustained Activation of ERKs Requires Rap1

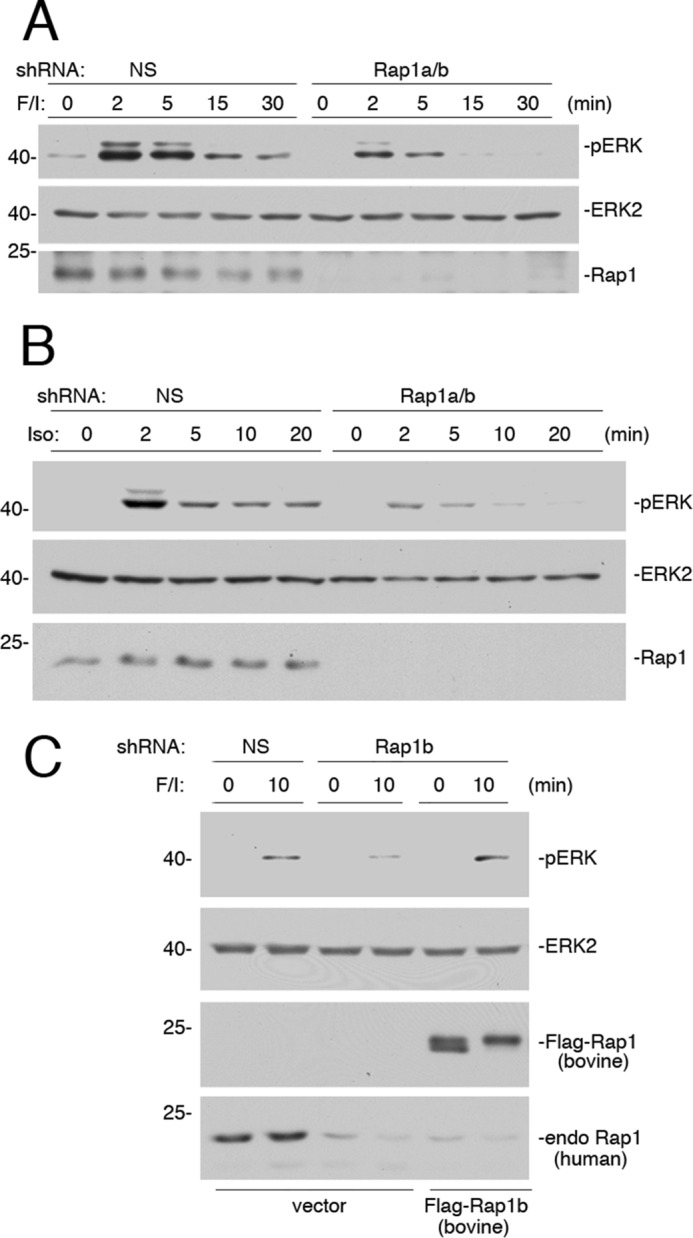

Rap1 has been proposed to mediate cAMP/PKA activation of ERKs in a variety of cell types (20, 21, 23). We examined whether it contributes to ERK activation by F/I in Hek293 cells as well. Rap1 exists as one of two highly homologous isoforms, Rap1a and Rap1b (37). The combined expression of two shRNAs, designed against Rap1a and Rap1b, respectively, completely blocked cAMP activation of ERKs during the sustained phase of ERK activation and partially blocked the early phase of ERK activation by F/I (Fig. 6A). Given the findings shown in Fig. 1, we propose that Rap1 contributes, along with Ras, to this early phase. Similar results were seen when examining isoproterenol (Fig. 6B). The controls to determine the ability of an shRNA-resistant cDNA for Rap1b to reverse the effects of its shRNA are shown (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Small G protein Rap1 mediates the sustained portion of ERK activation by cAMP. A, Hek293 cells transfected with either NS or shRNA against Rap1a/b were treated with F/I for the times indicated. The levels of pERK and total ERK2 are shown in the 1st and 2nd panels, respectively. The efficacy of the Rap1 knockdown is shown in the 3rd panel. B, cells transfected with either NS shRNA or shRNA against Rap1a/b were treated with isoproterenol (Iso) for the times indicated. The levels of pERK and total ERK2 are shown in the 1st and 2nd panels, respectively. The efficacy of the Rap1 knockdown is shown in the 3rd panel. C, cells were transfected with NS shRNA or shRNA against human Rap1b and either vector or FLAG-tagged shRNA-resistant Rap1b (bovine FLAG-Rap1b). Cells were treated with F/I for 10 min or left untreated, lysed, and examined by Western blotting. The levels of activation of ERK (pERK) and levels of total ERK2 are shown in the 1st and 2nd panels, respectively. The levels of FLAG-Rap1b (bovine) and endogenous (endo) human Rap1 are shown in the bottom two panels, respectively.

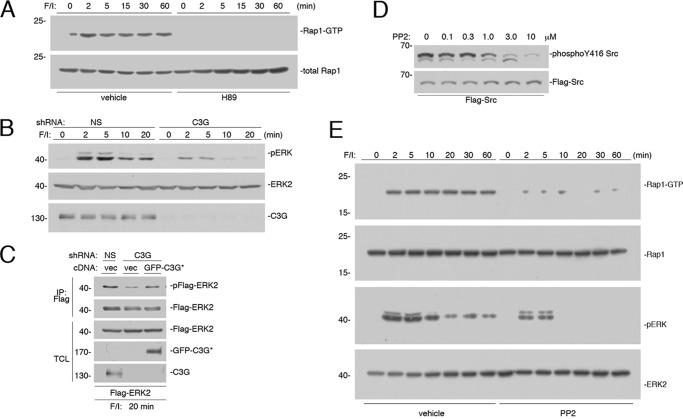

Unlike Ras, Rap1 activation was blocked by H89 (Fig. 7A). This PKA dependence is consistent with the known role for the Rap1 exchanger C3G in PKA-dependent activation of Rap1 (21, 23). A dominant role for C3G during the sustained phases of ERK activation was shown using shRNA knockdown of C3G (Fig. 7B). Similar to the actions of H89 and shRNA against Rap1 on ERK activation, a portion of the early phase of ERK activation was also inhibited to a limited extent by shRNA knockdown of C3G (Fig. 7B). The controls to determine the ability of an shRNA-resistant cDNA for C3G to reverse the effects of its respective shRNA are shown (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

PKA-dependent activation of Rap1 requires C3G. A, Hek293 cells were treated with F/I for the times indicated and pretreated with H89 or vehicle, as indicated. Rap1 activity (Rap1-GTP) was measured and shown in the 1st panel. Levels of total Rap1 are shown in the 2nd panel. B, cells transfected with either NS shRNA or shRNA against C3G were treated with F/I for the times indicated. The levels of pERK and total ERK2 are shown in the 1st and 2nd panels, respectively. The efficacy of the C3G knockdown is shown in the 3rd panel. C, cells were transfected with FLAG-ERK2 and either NS shRNA or shRNA against C3G and either vector or GFP-tagged shRNA-resistant C3G (GFP-C3G*), as indicated. Cells were treated with F/I for 20 min, lysed, and subjected to FLAG IP. The levels of FLAG-ERK2 activation (pFLAG-ERK2) and total FLAG-ERK2 within the IP are shown in the top two panels. The levels of total ERK2, GFP-C3G*, and C3G within the TCL are shown in the lower three panels, respectively. D, cells were transfected with FLAG-Src and treated with increasing doses of PP2 as indicated. The levels of phosphorylation of Y416 Src were determined using the phospho-Y416 antibody (top panel). The levels of FLAG-Src were determined using the FLAG antibody (bottom panel). E, cells were treated with F/I for the times indicated and pretreated with 2.5 μm PP2 or vehicle, as indicated. Rap1-GTP was measured in the 1st panel. Total levels of Rap1 are shown in the 2nd panel. The levels of pERK and total ERK2 are shown in the 3rd and 4th panels, respectively.

cAMP/PKA activation of C3G requires the tyrosine kinase Src, in Hek293 (38), as well as other cell types (39, 40). PP2, an inhibitor of Src family kinases, inhibits the basal autophosphorylation of Src on Tyr-416 with an IC50 of roughly 0.5–1.0 μm (Fig. 7D), which is consistent with previous reports (41). Based on these results, we utilized a concentration of PP2 (2.5 μm) that blocked most of the phosphorylation of Tyr-416 in these cells (Fig. 7D). At this concentration, Rap1 activation was completely blocked (Fig. 7E). 2.5 μm PP2 also selectively blocked the sustained portion of cAMP activation of ERKs (Fig. 7E), consistent with the known Rap1 dependence of this portion of ERK activation (38–40). Taken together, these data are consistent with roles for both Rap1 and Ras in the early phase and a selective role for Rap1 in the later phase of ERK activation by F/I.

Interestingly, ERK activation at early time points was also partially reduced by 2.5 μm PP2. Most of this inhibition reflects the loss of early Rap1 signaling, but a portion of this inhibition may reflect an inhibition of a second target of Src, the Ras effector C-Raf. Both Raf isoforms B-Raf and C-Raf couple to ERKs (42), but only C-Raf requires Src (43). The importance of C-Raf versus B-Raf is examined below.

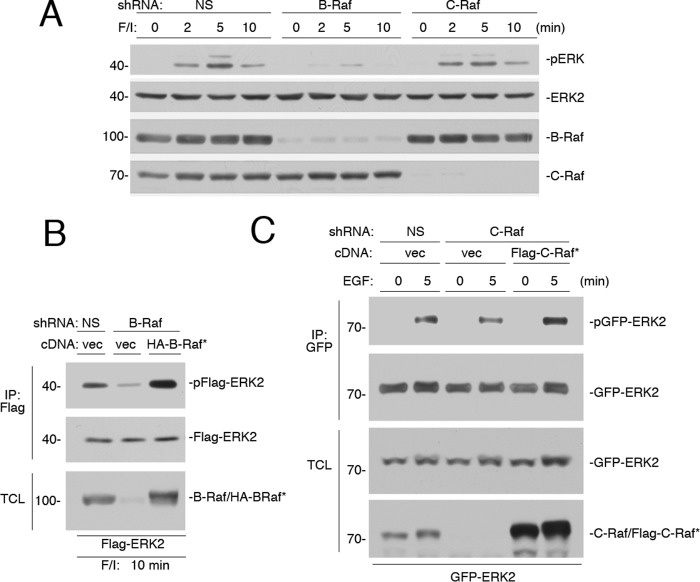

Initial Activation of ERKs Utilizes Both B-Raf and C-Raf

To determine the contribution of each Raf isoform (C-Raf and B-Raf) for ERK activation by cAMP, we utilized shRNAs specific for either human B-Raf or C-Raf. shRNA for B-Raf largely eliminated the activation of ERKs (2–10 min) (Fig. 8A). The residual ERK activation seen at 5 min of F/I treatment in the presence of B-Raf knockdown may represent the C-Raf-dependent portion of this early activation (Fig. 8A). The controls showing the ability of an shRNA-resistant cDNA for B-Raf to reverse the effects of B-Raf shRNA on F/I activation of ERKs are shown (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

B-Raf is required for the sustained activation of ERKs by cAMP. A, Hek293 cells were transfected with NS shRNA, or shRNA against B-Raf or C-Raf, and treated with F/I for 0, 2, 5, and 10 min, as indicated. The endogenous levels of pERK and total ERK2, and the efficacies of the shRNAs are shown. B, cells were transfected with NS shRNA or shRNA against B-Raf. Cells were also transfected with FLAG-ERK2 and either vector or HA-tagged shRNA-resistant B-Raf (HA-B-Raf*). Cells were treated with F/I for 10 min, lysed, and subjected to FLAG IP. The levels of ERK activation (pFLAG-ERK2), total FLAG-ERK2 within the IP are shown in the 1st and 2nd panels. The levels of B-Raf within the TCL are shown. Note that both endogenous B-Raf and HA-B-Raf* can be seen as a doublet in the 3rd lane. C, cells were transfected with GFP-ERK2 and NS shRNA or shRNA against C-Raf and either vector or FLAG-tagged shRNA-resistant C-Raf (FLAG-C-Raf*). Cells were treated with EGF for 5 min or left untreated, lysed, and subjected to GFP IP. The levels of activation of GFP-ERK2 (pGFP-ERK2) and total GFP-ERK2 within the IP are shown in the 1st and 2nd panels, respectively. The levels of GFP-ERK2 within the TCL are shown in the 3rd panel. The levels of C-Raf and FLAG-C-Raf* within the TCL are shown in the 4th panel.

In contrast to the results with B-Raf knockdown, the effect of C-Raf knockdown was minimal, with a very modest effect on ERK activation at 5 min of F/I treatment (Fig. 8A). This suggests that Ras-dependent ERK activation was largely B-Raf-dependent. As expected, C-Raf knockdown had no effect at later times (Fig. 8A), because these later Rap1-dependent signals couple exclusively through B-Raf (44). In light of the small effect of C-Raf shRNA on F/I stimulation of ERKs, the controls used to determine the ability of an shRNA-resistant cDNA for C-Raf to reverse the effect of C-Raf shRNAs were conducted with EGF, whose signaling to ERKs has a measurable C-Raf component (Fig. 8C).

The effect of B-Raf on early ERK activation was more pronounced than that of C-Raf. This is largely due to the contribution of Rap1 at these time points, which can only activate B-Raf (44). It is also due to the large B-Raf component of Ras signaling to ERKs, which reflects the ratio of B-Raf to C-Raf in these cells. B-Raf was roughly two to three times more abundant than C-Raf In Hek293 cells (data not shown).

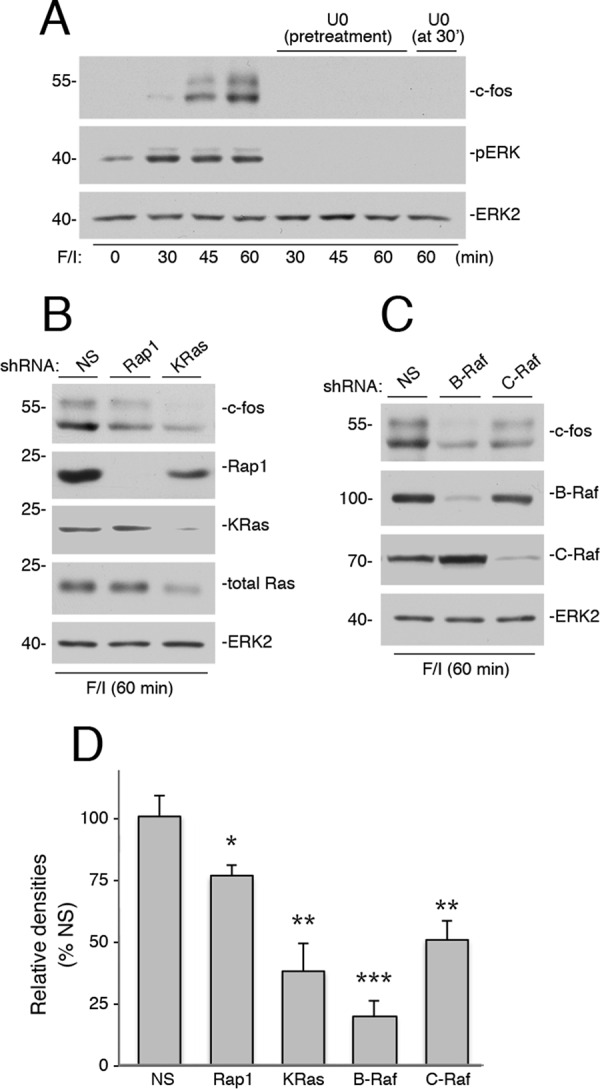

c-FOS Induction by cAMP Requires Both Ras and Rap1

A physiological role of sustained activation of ERKs is the transcription and stabilization of a range of transcription factors, including c-FOS (19). To examine the role of Ras, Rap1, B-Raf, and C-Raf in these processes, we examined the induction/stabilization of the transcription factor c-FOS. Like many other transcription factors (15), c-FOS activation requires a sequence of two ERK-dependent events. First, ERK-dependent activation of c-FOS transcription leads to newly synthesized c-FOS protein. The c-FOS protein is intrinsically unstable and requires additional ERK phosphorylations to ensure its stability (and detection by Western blotting). Therefore, increases in c-FOS protein levels require both rapid and sustained ERK activation (17, 19, 46).

In Hek293 cells, cAMP induction of c-FOS protein required ERK, as F/I induced a high level of c-FOS protein at 45 and 60 min after stimulation that was blocked by the MEK inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 9A). This block was present even when U0126 was applied 30 min after F/I application, demonstrating the requirement of late ERK activation for induction of c-FOS protein by cAMP. Both Rap1 and KRas were required for maintaining maximal c-FOS protein levels (Fig. 9, B and D), although KRas had a more pronounced effect on c-FOS protein levels, presumably due to its essential role in c-FOS transcription (19). Both B-Raf, and to a lesser degree, C-Raf were also required for maximal c-FOS protein levels (Fig. 9, C and D). Taken together these data are consistent with a model of cAMP regulation of c-FOS requiring both the rapid and the sustained activation of ERKs.

FIGURE 9.

Ras, Rap1, C-Raf, and B-Raf are all required for cAMP-dependent induction of c-FOS protein. A, Hek293 cells were treated with F/I for the times indicated in the presence and absence of U0126. In one condition, U0126 was applied at 30 min after F/I, and cells were harvested at 60 min. The endogenous levels of c-FOS were detected by Western blotting (1st panel). The levels of pERK and total ERK2 are shown (2nd and 3rd panels). B, cells were transfected with NS shRNA or shRNA against human Ras and Rap1, as indicated, and treated with F/I for 60 min. The levels of c-FOS are shown in the upper panel. The levels of Rap1, KRas, and total Ras are shown in the middle three panels, respectively, Total ERK2 levels are shown as a loading control (bottom panel). C, cells were transfected with NS shRNA, or shRNA against human B-Raf, and C-Raf, as indicated, and treated with F/I for 60 min. The levels of c-FOS are shown in the 1st panel. The levels of B-Raf and C-Raf are shown in the 2nd and 3rd panels, respectively, Total ERK2 levels are shown as a loading control (4th panel). D, shRNA data from three independent experiments representing those shown in B and C are presented as bar graphs, with c-FOS levels calculated by ImageJ densitometry and presented as relative densities normalized to the average densities seen in NS-treated cells. Error bars show standard error. Significance of the differences between densities in each condition and those seen in NS controls was assessed by unpaired Student's t tests (NS = not significant, * = <0.05, and ** = <0.01, and *** = <0.001).

Discussion

In this study, we report a mechanism for the cooperative actions of Ras and Rap1 in cAMP activation of ERKs. In Hek293 cells, Rap1 contributes to the sustained portion of cAMP/PKA activation of ERKs, whereas Ras contributes to the rapid (and transient) portion. This cooperation between Rap1 and Ras in cAMP/PKA activation of ERKs has not been reported previously.

Using shRNA knockdown of either Ras or Rap1 in Hek293 cells, we have defined two distinct temporal phases of cAMP activation of ERKs. We show that Ras was required for the rapid phase and Rap1 was required for the sustained phase of ERK activation by cAMP. Ras activation by cAMP was rapid and transient, returning to baseline within 5 min. The transient nature of this activation may account for why it was not appreciated in earlier studies (21, 38). Ras-dependent activation of ERKs was also rapid, showing a robust activation at 2 and 5 min that returned to baseline levels by 10 min.

Ras activation of ERKs generally requires the recruitment of either C-Raf or B-Raf (48). PKA blocks the recruitment of both C-Raf and B-Raf to Ras to terminate Ras action. This occurs, in part, through the PKA phosphorylation of C-Raf on Ser-259 and B-Raf on Ser-365. Each of these phosphorylations uncouples their respective Raf isoforms from binding to Ras-GTP (49, 50). Although PKA was dispensable for Ras activation by cAMP, we propose that PKA plays a role in terminating Ras action triggered by cAMP. That this action of cAMP is terminated by PKA dictates that Ras activation by cAMP will be rapid and transient. It is possible that the loss of Raf binding to Ras contributes to the transient nature of Ras activation by exposing bound GTP to rapid hydrolysis by RasGAP.

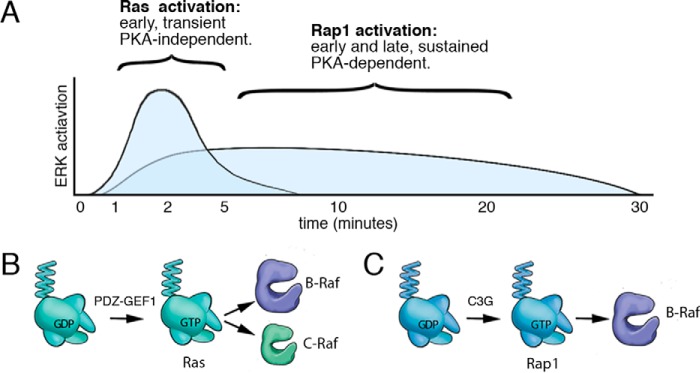

In contrast to Ras, Rap1 activation by cAMP was sustained. Like Ras, Rap1 activation was required for Rap1 to bind to effectors (51, 52), and the sustained activation of Rap1 was associated with the prolonged coupling of B-Raf to ERKs. Rap1 activation by cAMP was dependent on PKA and mediated by the Rap1 exchanger C3G, consistent with other studies (40, 53). These temporal requirements for both Ras and Rap1 were similar to those seen using the β-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol, suggesting that hormones coupled to cAMP can activate ERKs via similar pathways. These combined actions of Ras and Rap1 may explain previous studies examining the activation of ERKs by hormones linked to cAMP, where both Ras and Rap1 were shown to be required (39, 54–56). These actions of Ras and Rap1 are depicted in Fig. 10.

FIGURE 10.

Model of cAMP activation of Ras and Rap1. A, time course of ERK activation by cAMP is shown. cAMP activation of ERKs has both a Ras and a Rap1 component. The Ras component is rapid and transient, contributing to the early phase (2–5 min) of ERK activation. The Rap1 component is more modest in magnitude but is both early (2–5 min) and sustained (10–30 min). Although Rap1 and Ras both contribute to the early rapid component of ERK activation, Rap1 is solely responsible for the later sustained component. The Ras component does not require PKA, whereas the Rap1 component does. B, PKA-independent activation of Ras via cAMP occurs via cAMP-activated GEFs (PDZ-GEF1 in Hek293 cells). This results in the direct binding of Ras-GTP to the Ras-binding domains of B-Raf and C-Raf. Because B-Raf is more abundant than C-Raf in Hek293 cells, the action of B-Raf predominates at these early time points of ERK activation. C, PKA-dependent activation of Rap1 via cAMP occurs via cAMP/PKA-activated GEFs (chiefly C3G in Hek293 cells). This results in the binding of Rap1-GTP to B-Raf. Because Rap1 can only activate B-Raf, only B-Raf participates in the sustained phase of ERK activation.

Ras and Rap1 differ in their utilization of Raf isoforms to activate ERKs. We show that the late phase of cAMP activation of MAPK signaling exclusively uses the Raf isoform B-Raf but not the Raf isoform C-Raf. We have previously proposed that Rap1 cannot activate C-Raf because it cannot position C-Raf near the kinases that carry out the required phosphorylations at Ser-338 and Tyr-341 within the N-region (44). Co-localization of B-Raf with these kinases is not needed for B-Raf activation because homologous phosphorylation sites within the N-region of B-Raf are either constitutively phosphorylated (Ser-445) or replaced by phosphomimetic amino acids (Asp-448 and Asp-449) (43). We show that the role of C-Raf is limited to the Ras-dependent portion of this early phase. The extent of C-Raf's contribution to Ras activation of ERK is likely influenced by the relative levels of the two Ras effectors B-Raf and C-Raf. The larger contribution of B-Raf to the Ras component of ERK signaling can be largely explained by the predominance of B-Raf protein levels in these cells, compared with C-Raf.

Specific aspects of cAMP activation of Ras remain unresolved. We show that the PKA-independent activation of Ras and ERKs by cAMP required PDZ-GEF1. Previous reports have shown that PDZ-GEF1 can act either as a Ras GEF (31, 57, 58) or Rap1 GEF (20, 26, 32, 37). PDZ-GEF1 has been reported to be activated by cAMP in a PKA-independent manner (20, 31), but its mode of activation by cAMP has been unclear. PDZ-GEF1 has a putative cyclic nucleotide-binding domain (cNBD) that can bind cAMP in vitro (31). This cNBD lacks two conserved residues that are present in other cNBDs, including those present in both Epac and PKA. The ability of the PDZ-GEF1 cNBD to bind cAMP in vitro has been controversial, with some groups showing binding (20, 31) and others not (25, 32, 59). Moreover, the physiological role of this domain has been questioned, in part because of the inability of guanine nucleotide exchange assays of recombinant PDZ-GEF1 to show regulation by cAMP in vitro (25, 35). To examine the role of cAMP binding in vivo, we used the mutant PDZ-GEF1 K211D that disrupts cAMP binding to this cNBD in vitro (31). PDZ-GEF1 K211D could not support Ras activation in vivo, showing that an intact cNBD is required for cAMP activation of PDZ-GEF1 and the resultant activation of Ras and ERKs.

One explanation for the difference between the activation of PDZ-GEF1 by cAMP in vitro and activation of PDZ-GEF1 by F/I in cells may be that PDZ-GEF1 needs to be properly localized and/or oriented to specific membrane domains to function properly. Targeting to physiological sources of cAMP synthesis may also be important. PDZ-GEF1 has a PDZ domain that targets it to membrane proteins, including the β1-adrenergic receptor (58). The local concentrations of cAMP achievable downstream of the β1-adrenergic receptor may be sufficiently high to bind and activate PDZ-GEF1, enabling it to activate the pool of Ras that is localized to that membrane domain. Alternatively, binding of PDZ-GEF1 to the β1 receptor may allosterically enhance cAMP binding to the cNBD of PDZ-GEF1. Either possibility could occur despite the inability of cAMP to activate PDZ-GEF1 in vitro.

β-Adrenergic agonists activated Ras and ERKs to levels similar to that seen with forskolin, an agent that activates all membrane adenylate cyclases, including those downstream of the β-adrenergic receptors (27). This suggests that only specific subsets of the adenylate cyclases that are activated by forskolin are operationally linked to Ras. We propose that only the adenylate cyclases lying downstream of the β1-adrenergic receptor are functionally linked to PDZ-GEF1 and Ras activation. Taken together, these data support the findings of Rotin and co-workers (31, 57, 58) that the β1 receptor is physically linked to PDZ-GEF1.

The combined activations of Ras and Rap1 by cAMP may provide a physiological mechanism to maintain ERK signaling, whose temporal dynamics is critical for many cellular processes (46, 56). The physiological importance of sustained ERK activation can be seen in the regulation of c-FOS protein levels (15, 46). This requirement of sustained activation of ERKs for c-FOS expression has been shown previously for selected growth factors (15, 45). c-FOS is an immediate-early gene that is not expressed basally but is induced by ERK signaling in two ways as follows: 1) ERKs induce c-FOS transcription; 2) ERKs phosphorylate newly translated c-FOS protein to stabilize it.

We show that blocking ERK activation even after ERK-dependent transcription has occurred results in undetectable c-FOS protein levels. For this reason, c-FOS protein levels are a robust read-out of sustained ERK activation (15). Here, we show that the induction and maintenance of c-FOS protein levels by cAMP also requires the sustained activation of ERKs. This need for sustained activation of ERKs is reflected in the requirement for Ras, Rap1, C-Raf, and B-Raf in maintaining the levels of c-FOS protein following cAMP stimulation.

In summary, we propose a two-step model to explain how cAMP activates ERKs in Hek293 cells. The first step is PKA-independent and requires Ras. The second step is PKA-dependent and requires Rap1. Together both pathways ensure that ERK activation by cAMP is both rapid and sustained.

Experimental Procedures

Chemicals

Forskolin was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN). IBMX and H89, U0126, and PP2 were purchased from Calbiochem. Isoproterenol and epidermal growth factor (EGF) were purchased from Sigma.

Plasmids

PDZ-GEF1 was provided by Lawrence Quilliam (University of Indiana, Indianapolis) (26) and cloned into the vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) containing an N-terminal FLAG epitope. References to the Rap1 cDNA refer to the bovine Rap1b sequence. The construction of vectors containing FLAG-Rap1b has been described previously (44, 49, 60). The FLAG-PDZ-GEF1 K211D was generated by site-directed mutagenesis of the corresponding plasmids using the QuikChangeTM kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). C3G was provided by Michiyuki Matsuda (Kyoto University) (61) and tagged with GFP at its N terminus. Tagged and mutant versions of human B-Raf, C-Raf, KRas, and HRas have been described previously (40, 44, 49, 62).

The shRNA-resistant mutants of FLAG-PDZ-GEF1(WT or K211D) were generated by mutagenesis of GAGAGATTGTTATGGTGAA to GCGAGATCGTGATGGTGAA. The mutations here and below are underscored. The shRNA-resistant mutant of FLAG-KRas was generated by mutagenesis of CGAATATGATCCAACAATA to CGAGTATGACCCTACAATA. The shRNA-resistant mutant of FLAG-HRas was generated by mutagenesis of AGGAGGAGTACAGCGCCAT to AGGAAGAATACAGCGCAAT. The bovine Rap1b was used as the shRNA-resistant Rap1b, as it was resistant to an shRNA designed against human Rap1b. The human C3G cDNA was shRNA-resistant, as the shRNA was designed from the mRNA's non-coding region (63). The shRNA-resistant mutant of FLAG-C-Raf was generated by mutagenesis of CATCAGACAACTCTTATTG to CATCAGGCAGCTCTTGTTG. The shRNA-resistant mutant of HA-B-Raf was generated by mutagenesis of ACAGAGACCTCAAGAGTAA to ACAGAGATCTGAAGAGCAA.

RNA Interference

Complementary pairs of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. (Coralville, IA), annealed, and cloned into the pSUPER-neo+GFP vector (OligoEngine, Seattle, WA). The shRNA for Rap1a was described previously (37, 49, 62, 64, 65). The sense sequences of shRNA oligonucleotides are as follows: PDZ-GEF1 shRNA, GAGAGATTGTTATGGTGAA, designed from the human sequence corresponding to an effective rat PDZ-GEF1 siRNA (37); HRas shRNA, AGGAGGAGTACAGCGCCAT; C-Raf shRNA, CATCAGACAACTCTTATTG (49, 64); B-Raf shRNA, ACAGAGACCTCAAGAGTAA (49, 65); KRas shRNA, CGAATATGATCCAACAATA (Dharmacon siRNA); Rap1b shRNA, GGACAAGGATTTGCATTAG (66) and ACAGCACAGTCCACATTTA (67); C3G shRNA, GGGTTGTGTGAACTGAAAT (63); and non-specific shRNA, GCGCGCTTTGTAGGATTCG (62).

Antibodies

Anti-ERK2 (sc-1647), anti-B-Raf (sc-9902), anti-C-Raf (sc-133), anti-Rap1a/b (sc-65), anti-c-FOS (sc-166940, sc-7202), anti-KRas (sc-30, sc-522), anti-C3G (sc-869), and agarose-coupled anti-Myc (sc-40AC) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Agarose-coupled anti-FLAG (M2), and anti-FLAG (M2) were from Sigma. Anti-Myc (MA1-21316) was from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Rockford, IL). Anti-pan-Ras (Ras10) was from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Anti-phospho-ERK (T201 and Y204) (Ab 9101) and phospho-Src (Tyr-416) antibody (Ab 2101) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-GFP (A-11122) was purchased from Life Technologies, Inc. Anti-PDZ-GEF1 was from Novus Biological (Littleton, CO). Anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies for Western blottings were from GE Healthcare and Bio-Rad.

Cell Culture Conditions and Transfections

Hek293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Transient transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions and serum-starved prior to treatment. The control vector, pcDNA3, was included in each set of transfections to ensure that each plate received the same amount of transfected DNA. Cells were treated with 10 μm forskolin and 100 μm IBMX for 20 min unless otherwise indicated. This treatment is designated F/I in the text and figures. Isoproterenol was used at 100 μm. EGF was used at 10 ng/ml. The inhibitors H89 and PP2 were applied at 10 and 2.5 μm, respectively, 20 min prior to treatment with F/I.

shRNA experiments were conducted on cells split into 6-well plates in DMEM, 10%BS. 3–6 μg of plasmid DNA encoding shRNAs were mixed with the transfection reagent Lipofectamine 2000 in a fixed ratio (1 μg/2 μl) in Opti-MEM following the manufacturer's instructions. After 2 days, cells were serum-starved overnight and subjected to experimental treatments.

Cardiac Myocytes

Hearts were harvested from C57/BL6 mice (P7) under anesthesia, minced, trypsinized, and cultured as described (68, 69). Non-adherent cells were removed and cells passaged in DMEM, 10% FBS. All animal care was conducted according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval.

Western Blotting

Immunoprecipitations and Western blotting were performed as described previously (40, 47). Thermo Scientific PageRuler Prestained Protein Ladder was used as protein size indicators in all gels. Active Rap1 was assayed using GST-Ral-GDS in an in vitro pulldown assay as described previously (45). Active Ras was assayed using a Ras activation assay kit (Cytoskeleton Inc., Denver, CO) and performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. In all cases, representative Western blottings of at least three independent experiments are shown. When data from multiple gels were combined, the band densities were assessed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Relative densities are presented with standard error and significance, as analyzed by unpaired Student's t tests.

Author Contributions

P. J. S. S. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. Y. L. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments shown in Figs. 1–8. T. J. D. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments shown in Figs. 2 and 3. M. T. provided technical assistance and contributed to the preparation of all reagents. K. E. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments determining relative Raf expression levels. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Andréy Shaw (Washington University, St. Louis, MO) and Lawrence Quilliam (University of Indiana, Indianapolis) for selected plasmid constructs.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK090309 and R21 CA191392-01. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- GEF

- guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- IBMX

- 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- F/I

- forskolin and IBMX

- C3G

- Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor 1

- PDZ domain

- post-synaptic density protein (PSD95), Drosophila disc large tumor suppressor (Dlg1), and zonula occludens-1 protein (zo-1) domain

- Ab

- antibody

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- TCL

- total cell lysate

- NS shRNA

- non-specific shRNA

- cNBC

- cyclic nucleotide-binding domain

- Epac

- exchange proteins activated by cAMP

- NS

- nonspecific

- RA domain

- Ras association domain

- H89

- N-(2-(p-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl)-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide

- U0126

- 1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(o-aminophenylmercapto)butadiene

- PP2

- 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine.

References

- 1. Gomez E., Pritchard C., and Herbert T. P. (2002) cAMP-dependent protein kinase and Ca2+ influx through L-type voltage-gated calcium channels mediate Raf-independent activation of extracellular regulated kinase in response to glucagon-like peptide-1 in pancreatic beta-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 48146–48151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ehses J. A., Pelech S. L., Pederson R. A., and McIntosh C. H. (2002) Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide activates the Raf-Mek1/2-ERK1/2 module via a cyclic AMP/cAMP-dependent protein kinase/Rap1-mediated pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37088–37097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fujita T., Meguro T., Fukuyama R., Nakamuta H., and Koida M. (2002) New signaling pathway for parathyroid hormone and cyclic AMP action on extracellular-regulated kinase and cell proliferation in bone cells. Checkpoint of modulation by cyclic AMP. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 22191–22200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van Kolen K., Dautzenberg F. M., Verstraeten K., Royaux I., De Hoogt R., Gutknecht E., and Peeters P. J. (2010) Corticotropin releasing factor-induced ERK phosphorylation in AtT20 cells occurs via a cAMP-dependent mechanism requiring EPAC2. Neuropharmacology 58, 135–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Le Péchon-Vallée C., Magalon K., Rasolonjanahary R., Enjalbert A., and Gérard C. (2000) Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptides stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinase in the pituitary cell line GH4C1 by a 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate pathway. Neuroendocrinology 72, 46–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Romano D., Magalon K., Ciampini A., Talet C., Enjalbert A., and Gerard C. (2003) Differential involvement of the Ras and Rap1 small GTPases in vasoactive intestinal and pituitary adenylyl cyclase activating polypeptides control of the prolactin gene. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51386–51394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kovalovsky D., Refojo D., Liberman A. C., Hochbaum D., Pereda M. P., Coso O. A., Stalla G. K., Holsboer F., and Arzt E. (2002) Activation and induction of NUR77/NURR1 in corticotrophs by CRH/cAMP: involvement of calcium, protein kinase A, and MAPK pathways. Mol. Endocrinol. 16, 1638–1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iacovelli L., Capobianco L., Salvatore L., Sallese M., D'Ancona G. M., and De Blasi A. (2001) Thyrotropin activates mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in FRTL-5 by a cAMP-dependent protein kinase A-independent mechanism. Mol. Pharmacol. 60, 924–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vuchak L. A., Tsygankova O. M., Prendergast G. V., and Meinkoth J. L. (2009) Protein kinase A and B-Raf mediate extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation by thyrotropin. Mol. Pharmacol. 76, 1123–1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morozov A., Muzzio I. A., Bourtchouladze R., Van-Strien N., Lapidus K., Yin D., Winder D. G., Adams J. P., Sweatt J. D., and Kandel E. R. (2003) Rap1 couples cAMP signaling to a distinct pool of p42/44MAPK regulating excitability, synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. Neuron 39, 309–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Monaghan T. K., Mackenzie C. J., Plevin R., and Lutz E. M. (2008) PACAP-38 induces neuronal differentiation of human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells via cAMP-mediated activation of ERK and p38 MAP kinases. J. Neurochem. 104, 74–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grewal S. S., Horgan A. M., York R. D., Withers G. S., Banker G. A., and Stork P. J. (2000) Neuronal calcium activates a Rap1 and B-Raf signaling pathway via the cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 3722–3728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yamaguchi T., Nagao S., Wallace D. P., Belibi F. A., Cowley B. D., Pelling J. C., and Grantham J. J. (2003) Cyclic AMP activates B-Raf and ERK in cyst epithelial cells from autosomal-dominant polycystic kidneys. Kidney Int. 63, 1983–1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. York R. D., Yao H., Dillon T., Ellig C. L., Eckert S. P., McCleskey E. W., and Stork P. J. (1998) Rap1 mediates sustained MAP kinase activation induced by nerve growth factor. Nature 392, 622–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murphy L. O., Smith S., Chen R. H., Fingar D. C., and Blenis J. (2002) Molecular interpretation of ERK signal duration by immediate early gene products. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 556–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Werlen G., Hausmann B., Naeher D., and Palmer E. (2003) Signaling life and death in the thymus: timing is everything. Science 299, 1859–1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pellegrino M. J., and Stork P. J. (2006) Sustained activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase by nerve growth factor regulates c-FOS protein stabilization and transactivation in PC12 cells. J. Neurochem. 99, 1480–1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eriksson M., Taskinen M., and Leppä S. (2007) Mitogen activated protein kinase-dependent activation of c-Jun and c-FOS is required for neuronal differentiation but not for growth and stress response in PC12 cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 210, 538–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murphy L. O., MacKeigan J. P., and Blenis J. (2004) A network of immediate early gene products propagates subtle differences in mitogen-activated protein kinase signal amplitude and duration. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 144–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Emery A. C., Eiden M. V., Mustafa T., and Eiden L. E. (2013) Rapgef2 connects GPCR-mediated cAMP signals to ERK activation in neuronal and endocrine cells. Sci. Signal. 6, ra51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schmitt J. M., and Stork P. J. (2000) beta 2-adrenergic receptor activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) via the small G protein rap1 and the serine/threonine kinase B-Raf. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25342–25350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stork P. J., and Schmitt J. M. (2002) Crosstalk between cAMP and MAP kinase signaling in the regulation of cell proliferation. Trends Cell Biol. 12, 258–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vossler M. R., Yao H., York R. D., Pan M. G., Rim C. S., and Stork P. J. (1997) cAMP activates MAP kinase and Elk-1 through a B-Raf- and Rap1-dependent pathway. Cell 89, 73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gloerich M., and Bos J. L. (2010) Epac: defining a new mechanism for cAMP action. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 50, 355–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de Rooij J., Boenink N. M., van Triest M., Cool R. H., Wittinghofer A., and Bos J. L. (1999) PDZ-GEF1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor specific for Rap1 and Rap2. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 38125–38130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rebhun J. F., Castro A. F., and Quilliam L. A. (2000) Identification of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for the Rap1 GTPase. Regulation of MR-GEF by M-Ras-GTP interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 34901–34908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Insel P. A., and Ostrom R. S. (2003) Forskolin as a tool for examining adenylyl cyclase expression, regulation, and G protein signaling. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 23, 305–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Seifert R., Lushington G. H., Mou T. C., Gille A., and Sprang S. R. (2012) Inhibitors of membranous adenylyl cyclases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 33, 64–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Buscà R., Abbe P., Mantoux F., Aberdam E., Peyssonnaux C., Eychène A., Ortonne J. P., and Ballotti R. (2000) Ras mediates the cAMP-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) in melanocytes. EMBO J. 19, 2900–2910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Rooij J., Zwartkruis F. J., Verheijen M. H., Cool R. H., Nijman S. M., Wittinghofer A., and Bos J. L. (1998) Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature 396, 474–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pham N., Cheglakov I., Koch C. A., de Hoog C. L., Moran M. F., and Rotin D. (2000) The guanine nucleotide exchange factor CNrasGEF activates ras in response to cAMP and cGMP. Curr. Biol. 10, 555–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liao Y., Kariya K., Hu C. D., Shibatohge M., Goshima M., Okada T., Watari Y., Gao X., Jin T. G., Yamawaki-Kataoka Y., and Kataoka T. (1999) RA-GEF, a novel Rap1A guanine nucleotide exchange factor containing a Ras/Rap1A-associating domain, is conserved between nematode and humans. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37815–37820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lorenz K., Schmitt J. P., Vidal M., and Lohse M. J. (2009) Cardiac hypertrophy: targeting Raf/MEK/ERK1/2-signaling. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41, 2351–2355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lohse M. J., Engelhardt S., and Eschenhagen T. (2003) What is the role of β-adrenergic signaling in heart failure? Circ. Res. 93, 896–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kuiperij H. B., de Rooij J., Rehmann H., van Triest M., Wittinghofer A., Bos J. L., and Zwartkruis F. J. (2003) Characterisation of PDZ-GEFs, a family of guanine nucleotide exchange factors specific for Rap1 and Rap2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1593, 141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liao Y., Satoh T., Gao X., Jin T. G., Hu C. D., and Kataoka T. (2001) RA-GEF-1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rap1, is activated by translocation induced by association with Rap1*GTP and enhances Rap1-dependent B-Raf activation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28478–28483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hisata S., Sakisaka T., Baba T., Yamada T., Aoki K., Matsuda M., and Takai Y. (2007) Rap1-PDZ-GEF1 interacts with a neurotrophin receptor at late endosomes, leading to sustained activation of Rap1 and ERK and neurite outgrowth. J. Cell Biol. 178, 843–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schmitt J. M., and Stork P. J. (2002) Gα and Gβγ require distinct Src-dependent pathways to activate Rap1 and Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43024–43032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Obara Y., Labudda K., Dillon T. J., and Stork P. J. (2004) PKA phosphorylation of Src mediates Rap1 activation in NGF and cAMP signaling in PC12 cells. J. Cell Sci. 117, 6085–6094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang Z., Dillon T. J., Pokala V., Mishra S., Labudda K., Hunter B., and Stork P. J. (2006) Rap1-mediated activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases by cyclic AMP is dependent on the mode of Rap1 activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 2130–2145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hanke J. H., Gardner J. P., Dow R. L., Changelian P. S., Brissette W. H., Weringer E. J., Pollok B. A., and Connelly P. A. (1996) Discovery of a novel, potent, and Src family-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Study of Lck- and FynT-dependent T cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 695–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Roskoski R., Jr.(2010) RAF protein-serine/threonine kinases: structure and regulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 399, 313–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mason C. S., Springer C. J., Cooper R. G., Superti-Furga G., Marshall C. J., and Marais R. (1999) Serine and tyrosine phosphorylations cooperate in Raf-1, but not B-Raf activation. EMBO J. 18, 2137–2148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Carey K. D., Watson R. T., Pessin J. E., and Stork P. J. (2003) The requirement of specific membrane domains for Raf-1 phosphorylation and activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3185–3196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Franke B., Akkerman J. W., and Bos J. L. (1997) Rapid Ca2+-mediated activation of Rap1 in human platelets. EMBO J. 16, 252–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Murphy L. O., and Blenis J. (2006) MAPK signal specificity: the right place at the right time. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 268–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu C., Takahashi M., Li Y., Dillon T. J., Kaech S., and Stork P. J. (2010) The interaction of Epac1 and Ran promotes Rap1 activation at the nuclear envelope. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 3956–3969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Marshall C. J. (1996) Ras effectors. Cur. Opin. Cell Biol. 8, 197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li Y., Takahashi M., and Stork P. J. (2013) Ras-mutant cancer cells display B-Raf binding to Ras that activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase and is inhibited by protein kinase A phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 27646–27657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dumaz N., and Marais R. (2003) Protein kinase A blocks Raf-1 activity by stimulating 14-3-3 binding and blocking Raf-1 interaction with Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 29819–29823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stork P. J. (2003) Does Rap1 deserve a bad Rap? Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 267–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Largaespada D. A. (2003) A bad rap: Rap1 signaling and oncogenesis. Cancer Cell 4, 3–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schmitt J. M., and Stork P. J. (2002) PKA phosphorylation of Src mediates cAMP's inhibition of cell growth via Rap1. Mol. Cell 9, 85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Alleaume C., Eychène A., Caigneaux E., Muller J. M., and Philippe M. (2003) Vasoactive intestinal peptide stimulates proliferation in HT29 human colonic adenocarcinoma cells: concomitant activation of Ras/Rap1-B-Raf-ERK signalling pathway. Neuropeptides 37, 98–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bouschet T., Perez V., Fernandez C., Bockaert J., Eychene A., and Journot L. (2003) Stimulation of the ERK pathway by GTP-loaded Rap1 requires the concomitant activation of Ras, protein kinase C, and protein kinase A in neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4778–4785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zeiller C., Blanchard M. P., Pertuit M., Thirion S., Enjalbert A., Barlier A., and Gerard C. (2012) Ras and Rap1 govern spatiotemporal dynamic of activated ERK in pituitary living cells. Cell. Signal. 24, 2237–2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Amsen E. M., Pham N., Pak Y., and Rotin D. (2006) The guanine nucleotide exchange factor CNrasGEF regulates melanogenesis and cell survival in melanoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pak Y., Pham N., and Rotin D. (2002) Direct binding of the β1-adrenergic receptor to the cyclic AMP-dependent guanine nucleotide exchange factor cNrasGEF leads to Ras activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7942–7952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ohtsuka T., Hata Y., Ide N., Yasuda T., Inoue E., Inoue T., Mizoguchi A., and Takai Y. (1999) nRap GEP: a novel neural GDP/GTP exchange protein for Rap1 small G protein that interacts with synaptic scaffolding molecule (S-SCAM). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 265, 38–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Takahashi M., Dillon T. J., Liu C., Kariya Y., Wang Z., and Stork P. J. (2013) Protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of Rap1 regulates its membrane localization and cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 27712–27723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tanaka S., Morishita T., Hashimoto Y., Hattori S., Nakamura S., Shibuya M., Matuoka K., Takenawa T., Kurata T., and Nagashima K. (1994) C3G, a guanine nucleotide-releasing protein expressed ubiquitously, binds to the Src homology 3 domains of CRK and GRB2/ASH proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 3443–3447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Liu C., Takahashi M., Li Y., Song S., Dillon T. J., Shinde U., and Stork P. J. (2008) Ras is required for the cyclic AMP-dependent activation of Rap1 via Epac2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 7109–7125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nolz J. C., Nacusi L. P., Segovis C. M., Medeiros R. B., Mitchell J. S., Shimizu Y., and Billadeau D. D. (2008) The WAVE2 complex regulates T cell receptor signaling to integrins via Abl- and CrkL-C3G-mediated activation of Rap1. J. Cell Biol. 182, 1231–1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chadee D. N., and Kyriakis J. M. (2004) MLK3 is required for mitogen activation of B-Raf, ERK and cell proliferation. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 770–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bhatt K. V., Hu R., Spofford L. S., and Aplin A. E. (2007) Mutant B-RAF signaling and cyclin D1 regulate Cks1/S-phase kinase-associated protein 2-mediated degradation of p27Kip1 in human melanoma cells. Oncogene 26, 1056–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wittchen E. S., Aghajanian A., and Burridge K. (2011) Isoform-specific differences between Rap1A and Rap1B GTPases in the formation of endothelial cell junctions. Small GTPases 2, 65–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gao L., Feng Y., Bowers R., Becker-Hapak M., Gardner J., Council L., Linette G., Zhao H., and Cornelius L. A. (2006) Ras-associated protein-1 regulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation and migration in melanoma cells: two processes important to melanoma tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cancer Res. 66, 7880–7888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Merkel M. J., Liu L., Cao Z., Packwood W., Young J., Alkayed N. J., and Van Winkle D. M. (2010) Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase preserves cardiomyocytes: role of STAT3 signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 298, H679–H687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. O'Connell T. D., Rodrigo M. C., and Simpson P. C. (2007) Isolation and culture of adult mouse cardiac myocytes. Methods Mol. Biol. 357, 271–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]