Abstract

Spirochetes are bacteria responsible for several serious diseases that include Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi), syphilis (Treponema pallidum), leptospirosis (Leptospira interrogans), and contribute to periodontal diseases (Treponema denticola)1. These spirochetes employ an unusual form of flagella-based motility necessary for pathogenicity; indeed, spirochete flagella (periplasmic flagella, PFs) reside and rotate within the periplasmic space2–11. The universal joint or hook that links the rotary motor to the filament is composed of approximately 120–130 FlgE proteins, which in spirochetes form an unusually stable, high-molecular weight complex (HMWC)9,12–17. In other bacteria, the hook can be readily dissociated by treatments such as heat18. In contrast, spirochete hooks are resistant to these treatments, and several lines of evidence indicate that the HMWC is the consequence of covalent cross-linking12,13,17. Here we show that T. denticola FlgE self-catalyzes an interpeptide cross-linking reaction between conserved lysine and cysteine resulting in the formation of an unusual lysinoalanine adduct that polymerizes the hook subunits. Lysinoalanine cross-links are not needed for flagellar assembly, but they are required for cell motility, and hence infection. The self-catalytic nature of FlgE cross-linking has important implications for protein engineering, and its sensitivity to chemical inhibitors provides a new avenue for the development of antimicrobials targeting spirochetes.

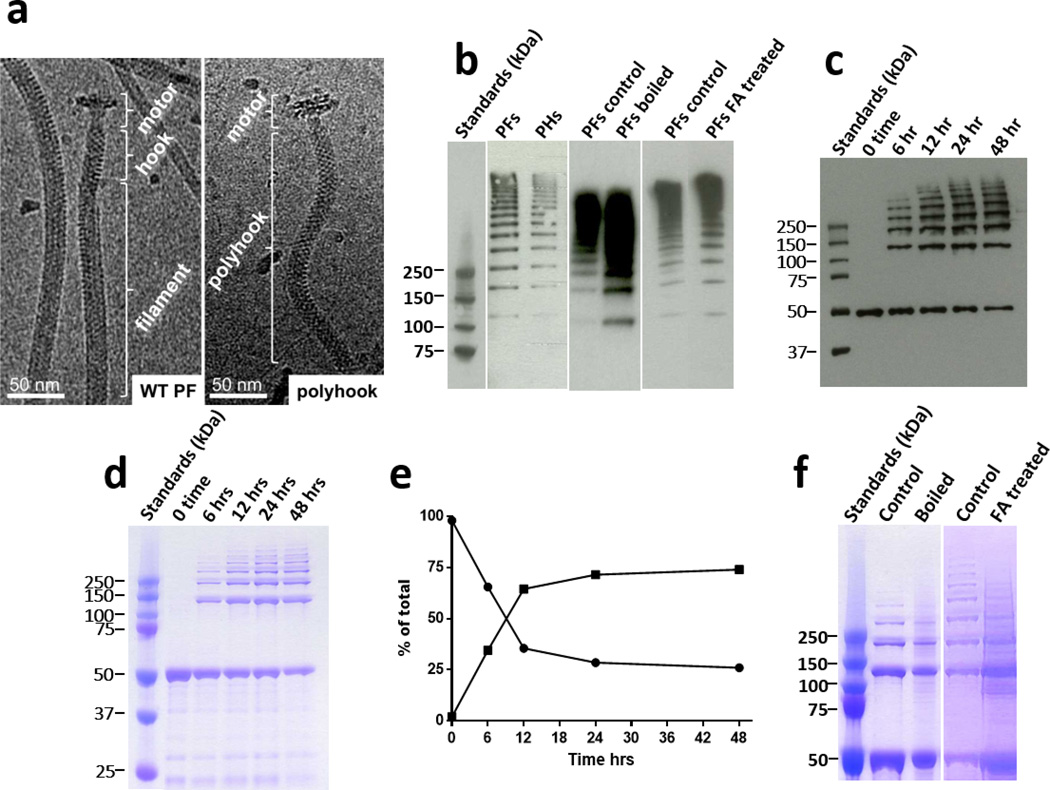

We systematically examined the nature and the synthesis of the FlgE cross-link in T. denticola, and also examined the role of cross-linking with respect to motility. The FlgE HMWC from T. denticola was isolated from the PFs of wild-type (WT) and from polyhooks (PHs) of the T. denticola FliK mutant (Fig. 1a). T. denticola FliK overproduces FlgE in the form of polyhooks and lacks flagellar filament proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1)14. As found previously for T. denticola, and also for Treponema phagedenis and B. burgdorferi, FlgE from purified PFs and PHs form a ladder on SDS-PAGE at masses greater than 200 kDa (monomer MW ~50 kDa; Fig. 1b)12–14,17. These HMWCs from PFs and PHs were relatively stable to boiling or treatment with formic acid (FA), 8M urea, or the thiol reductants β-mercaptoethanol (BME) and dithiothreitol (DTT) (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1). This remarkable stability indicates covalent linkages between subunits that are not disulfide bonds12,13,17,19. To investigate whether isolated FlgE proteins could also undergo cross-linking, we produced and purified recombinant T. denticola FlgE (rFlgE) as a His6-tagged protein. Dialysis against 1M ammonium sulfate, pH 8.5, at 4°C resulted in consistent, robust, and time-dependent polymerization (Fig. 1c,d). The amount and apparent mass of the HMWCs steadily increased with time up to 24 hrs, with approximately 25% remaining monomeric (Fig. 1e). Similar to FlgE derived from hook samples, the HMWC produced by rFlgE was stable to all disrupting agents tested (Fig.1f; Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, the covalent polymerization of FlgE is self-catalyzing and requires no additional proteins.

Fig. 1. Stability of FlgE high molecular weight complexes (HMWCs) derived from PFs periplasmic flagella (PFs), polyhooks (PHs), and rFlgE.

a. Representative cryoelectron- microscopy(cryo-EM) images of purified T. denticola PFs and PHs. b. Representative western blot of PFs and PHs using anti-FlgE antibodies, indicating that the HMWCs from PFs were stable to boiling and formic acid (FA). c. Time course of in vitro formation of the HMWC using western blot and (d) Imperial staining. The monomer has a mass of 50 kDa. e. The densitometry plot of the Imperial stained gel indicates that the HMWC (squares) is synthesized with a concomitant decrease of the rFlgE monomer (circles). f. Representative gel indicating the stability of the in vitro synthesized HMWC to boiling and FA.

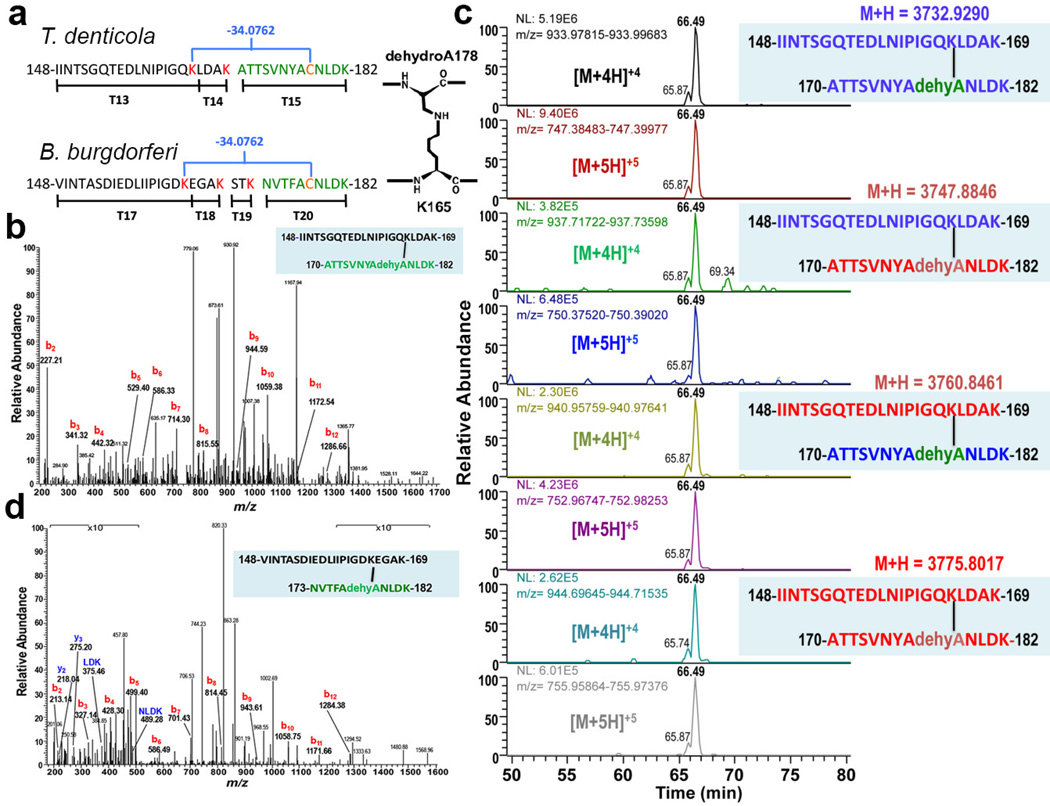

To identify the FlgE covalent cross-link, rFlgE monomer and multimer bands were isolated separately from SDS-PAGE gels and subjected to trypsin digestion followed by LC-MS analysis. The elution chromatograms (Supplementary Fig. 2) revealed a region of difference between the HMWC and monomer samples that was attributed to a peptide of 3732.9290 Da in the former (Fig. 2). The mass of this peptide corresponds to a stretch of FlgE that encompasses the tryptic peptides T13–T14–T15 (numbered for their order in sequence), with no internal cleavages, but additional mass loss of 16 Da (Fig. 2a). Alternatively, if the peptide contains one tryptic cleavage site it could comprise two segments from different subunits linked by a modification that removes 34 Da, the equivalent of two N, or O atoms or one S atom (and the respective associated protons; Fig. 2a). MS/MS fragmentation produced a b-ion series of sequence IINTSGQTED (Fig. 2b), which confirms that the peptide N-terminus belongs to T13 (Fig. 2a). However, no C-terminal y-ions are observed in the MS/MS spectrum, which is highly unusual (Fig. 2b). Also surprisingly, the mass includes no carbamidomethyl modification of the lone T15 cysteine residue resulting from the iodoacetamide treatment of the MS preparation. This absence suggests that there is no reactive thiol in the peptide, even though its sequence should include Cys178. To confirm that the 3732.9290 Da peptide contained the C-terminus of T15, a rFlgE N175A substitution was produced; this protein cross-linked and was shown by MS to generate a peptide of the expected altered mass (Supplementary Fig. 3). Consistent with the involvement of T13–T14–T15 in cross-linking, peptides T13, T14 and T15 have ~2.5× lower abundance in the HMWC compared to monomeric rFlgE (Supplementary Tables 1,2).

Fig. 2. Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of T. denticola and B. burgdorferi HMWCs indicates that the cross-link is lysinoalanine.

a. Trypsin fragments involved in cross-linking in T. denticola and B. burgdorferi. The blue brackets indicate the cross-links, with concomitant loss of mass (34.0762 Da). The cross link proposed for T. denticola involves C178 (orange), its conversion to dehydroalanine (dehydroA), and its link to K165 (red). b. MS/MS spectrum of T. denticola cross-linked peptide. Tryptic peptide at m/z = 747.39142+5 from in vitro rFlgE HMWC identifies a lysinoalanine cross-link. The b-ion series extends to the 12th N-terminal residue. No y-ions are observed. Data is representative of 3 analyzed peptides per 3 preparations. c. MS analysis of rFlgE proteins isotopically labeled to identify unique subunits of origin. Extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) of the cross-linked peptides were derived from mixtures of 14N-FlgE and 15zN-FlgE. T. denticola 15N-FlgE were recombinantly produced in E. coli grown on 15N-enriched minimal media. Purified 14N-FlgE and 15N-FlgE were then mixed and self-catalyzing cross-linking initiated. The resulting sample was run on SDS-PAGE, the multimer bands were digested with trypsin and analyzed by MS/MS. XICs reveal well-represented peptides for the four possible combinations of crosslinking (14N-labelling in blue, 15N-labelling in red). [M+nH]+n represents the protonation and charge state (n) of the peptide relative to the uncharged molecular ion (M). Data is representative of two samples. d. MS/MS spectrum of B. burgdorferi cross-linked peptide obtained from PHs. Peptide at m/z = 680.9638+5 from FlgE tryptic digest identifies a lysinoalanine cross-link. The series of b-ions extends to the 12th N-terminal residue. A short y-ion sequence is also observed (blue). Unlike the T. denticola cross-linked peptide, the sequence of the B. burgdorferi peptide is not contiguous with the coded amino acids due to an additional tryptic cleavage at residue 169 that removes amino acids STK from the C-terminus of the N-terminal peptide (Fig. 2a). Mass peaks at low and high m/z ratios are shown at 10× amplitude. Data representative of 3 analyzed peptides from one hook preparation.

To better define the origin of the 34 Da mass loss, high-resolution mass fragments from complete MS/MS data sets of the HMWC were evaluated for agreement with the ions predicted by the various possibilities (Supplementary Fig. 4). The data were most consistent with T13–T14–T15 undergoing one peptide hydrolysis (+H2O) and loss of SH2 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, the mass analysis indicates a lysinoalanine crosslink between one of the two internal Lys residues (165 or 169) and Cys178 that has converted to dehydroalanine (Fig. 2a). Indeed, amino acid analysis of the rFlgE HMWC and monomer samples revealed a substantially higher amount of lysinoalanine in the HMWC than in the monomer (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results are consistent with our finding that optimal in vitro HMWC synthesis occurs under alkaline conditions (Figure 1C,D.E)20; lysinoalanine formation is known to be enhanced by high pH21.

In order to unambiguously define the cross-linking pattern and show that the lysinoalanine adduct occurs between subunits, we performed cross-linking of natural abundance 14N-containing rFlgE and rFlgE isotopically labeled with 15N. MS/MS analysis of the HMWCs from the mixed sample revealed the expected 14N-14N and 15N-15N peptides, as well as variants corresponding to the two mixed species 14N-15N and 15N-14N (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 6). The isotope substitution patterns of the mixed peptides are fully consistent with a lysinoalanine cross-link between positions 165 and 178. Lending support to the hypothesis that Cys178 converts to dehydroalanine before or during reaction with Lys165, we found that BME inhibits cross-linking of rFlgE by producing a thioether linkage to dehydroalanine at residue 178 (Supplementary Fig. 7). Thiol groups are known inhibitors of lysinoalanine synthesis21.

To confirm that the in vitro catalyzed formation of the HMWC represents cross-linking in vivo, PHs purified from T. denticola FliK were shown by MS to contain the 3,732.9290 Da lysinoalanine containing peptide (Supplementary Fig. 8). We also determined that FlgE from another spirochete, B. burgdorferi, undergoes a similar cross-linking reaction. The B. burgdorferi FlgE sequence (53.9% identical to that of T. denticola) fortuitously contains an additional tryptic cleavage site between K165 and C178 and thus, the B. burgdorferi cross-linked peptide will comprise T17–T18 linked to non-contiguous T20 (Fig. 2a). PHs obtained from the B. burgdorferi FliK mutant12 were analyzed by MS/MS and shown to contain the expected cross-linked peptide (Fig. 2d). MS/MS spectra resolved both a b-ion series for the T17 N-terminus, and a short y-ion sequence for the T20 C-terminal NLDK residues (Fig. 2d), thereby providing unequivocal evidence for covalent cross-linking of B. burgdorferi FlgE in vivo.

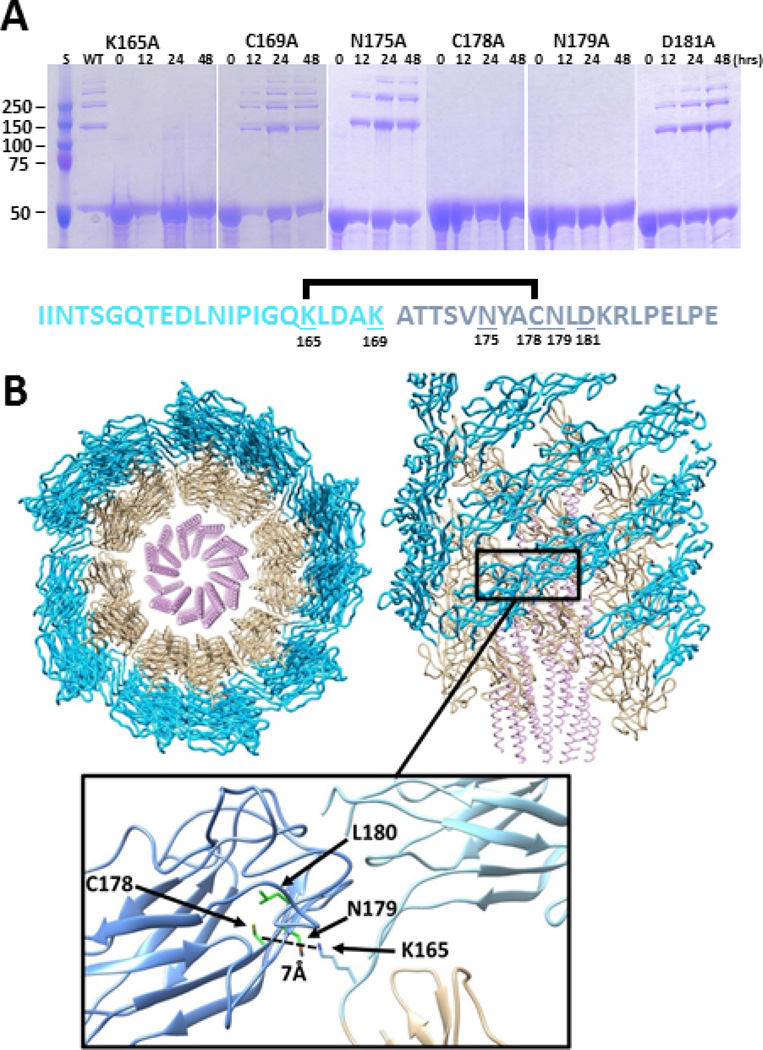

We then evaluated the ability of residue substitutions to alter cross-linking of rFlgE in vitro. As expected, the K165A and C178A substitutions completely abrogated any cross-linking (Fig. 3a), even after 1 week of incubation (Supplementary Fig. 1). Interestingly, the N179A variant was also completely inactive. In contrast, the rFlgE proteins containing K169A, N175A, and D181A substitutions effectively produced the HMWC (Fig. 3a). A phylogenetic analysis of FlgE proteins across bacterial species indicates that K165 is invariant in spirochetes and that position 178 is conserved as either Cys or Ser, the latter of which is also known to participate in lysinoalanine formation21 (Supplementary Fig. 9). Other bacteria do not conserve these residues (Supplementary Fig. 9) and hence the FlgE cross-link is likely an adaptation to the demands placed on the spirochete PFs. A homology model of T. denticola FlgE was constructed from the crystal structure of the S. enterica protein and this model was elaborated into a hook structure based on the 7 Å EM map of the S. enterica hook22 (Fig 3b). The symmetry of the S. enterica hook closely positions K165 of one T. denticola FlgE subunit relative to Cys178 and Asn179 of the adjacent subunit. However, in the FlgE crystal structure, Cys178 projects away from the interface and instead resides within a β-barrel of the FlgE D2 subunit (Fig 3b). Sequence conservation suggests that the T. denticola and S. enterica FlgE proteins have similar structures and thus, reaction with K165 would require a rearrangement of the Cys178 residue. The ability of T. denticola FlgE Cys178 to undergo conversion to dehydroalanine and react with BME does verify that the 178 side chain can become exposed.

Fig. 3. Mutagenesis identifies critical residues for cross-linking that are compatible with structural models of the hook.

a. rFlgE mutant proteins were incubated under conditions optimal for protein cross-linking and analyzed by SDS-PAGE over 48 hrs. Representative gels of mutants K165A, C178A, and N179A failed to form HMWCs. Approximately 75% of rFlgE from the WT (Figure 1d), and mutants K169A, D181A, and N175A were cross-linked over time. The T. denticola cross link of FlgE is shown, with the lysinoalanine cross link between K165 (light blue) of one subunit to dehydroalanine derived from C178 (dark blue) of another subunit; mutated residues are underlined. b. Model of the spirochete hook structure based on electron microscopy of S. enterica hook (PDB code: 3A69) and atomic coordinates of S. enterica FlgE D1 and D2 domains (PDB: code 1WLG). A segment of the hook is shown viewed down (left) and aligned with (right) the symmetry axis. The helical D0 domains of FlgE are in the center, followed by the D1 domains (tan) in the middle and the D2 domain (blue) on the outside. The cross-linking residue Lys165 (light blue) lies on the linker between the D1 and D2 domains (inset) and is predicted to be in close proximity (~ 7.0 Å) of Cys178 (dark blue) on the adjacent D2 subunit. Based on the crystal structure of S. enterica FlgE, Cys178 projects to the center of the D2 β-barrel. A change in conformation of this residue would be required to form the cross-link with the well-positioned Lys165. Indeed, a flip of Cys178 toward solvent would place the side chain close to the lysine amino group. The spirochete conserved Asn179 is solvent exposed and resides beside Lys165. Conserved Leu180 packs next to Cys178 in the β-barrel interior.

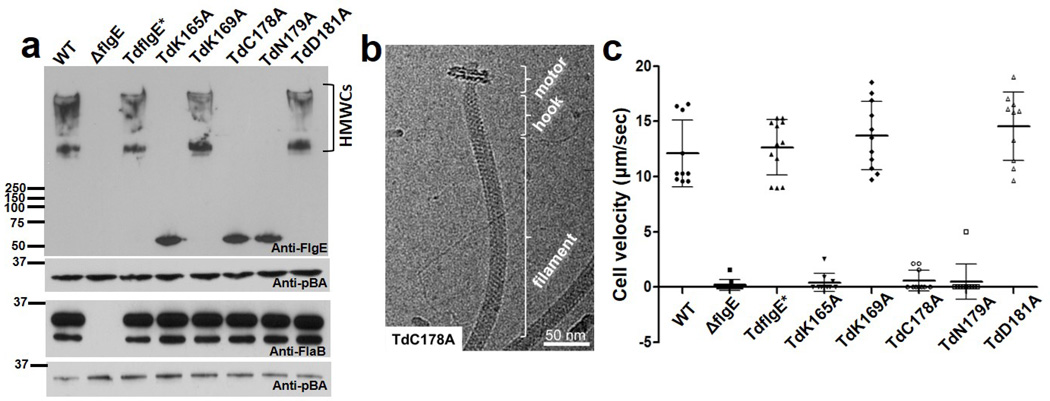

Results from the in vitro mutagenesis experiments suggested a strategy for assessing the importance of FlgE cross-linking for in vivo function. We constructed a T. denticola flgE deletion mutant (ΔflgE) and five mutants containing single residue substitutions in FlgE. We also constructed a strain with the WT flgE gene replacing ΔflgE (Td FlgE*). Western blot analysis indicated that FlgE was detected in the WT and mutants with the residue substitutions, but not in ΔflgE (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, FlgE HMWCs were detected in whole cell lysates from WT, TdflgE*, TdK169A, or TdD181A, but not from TdK165A, TdC178A, or TdN179A. Thus, K165, C178 and N179 are essential for the FlgE cross-linking both in vitro and in vivo. Previous studies have shown that T. denticola FlgE is required for flagellin (FlaB) protein synthesis, flagellar filament assembly, and motility23,24. Thus, we investigated the effect of the FlgE substitution mutants on flagellar filament assembly. Western-blot analysis of whole cell lysates with FlaB antibody detected no difference in reactivity in the substitution mutants compared to the WT (Fig. 4a). In contrast, no FlaB proteins were detected in the ΔflgE mutant. Cryoelectron microscopy (Cryo-EM) analysis confirmed that those mutants deficient in cross-linking produced normal appearing PFs (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 10). Furthermore, no difference in hook structure was evident among intact cells of WT and TdK165A, TdC178A, and TdN179A as observed in cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) analysis of the cell ends (Supplementary Fig. 11). We tested if the mutants that lacked cross-linking were deficient in motility. Cell tracking experiments indicated that the ΔflgE cells were totally non-motile (Fig. 4c). Importantly, mutant cells TdK165A, TdC178A, and TdN179A were unable to translate even though generated motion was evident along the cell bodies (Fig. 4c, supplementary videos 1–4). In contrast, the TdK169A and TdD181A mutant cells had similar swimming behaviors as that of the WT and TdFlgE* cells. These results indicate cross-linking of FlgE is essential for T. denticola motility.

Fig. 4. T. denticola mutants unable to form FlgE cross-links are deficient in motility but still form intact flagella.

a. Representative western blots of mutant cell lysates reacted with antibodies to FlgE and FlaB. pBA (T. denticola thiamine binding protein A) served as a loading control.31 TdFlgE* carries the WT flgE gene replacing the ΔflgE mutation. b. Representative Cryo-EM of TdC178A mutant indicating that its structure is similar to the WT (compare with Figure 1a). c. Cell velocities of mutants using computer based video tracking. Approximately 10 cells of each strain were tracked and plotted, and the error bars represent standard deviations (SD). P values of <0.01 (one way ANOVA) were considered significant. ΔflgE, TdK165A, TdC178A, and TdN179A were significantly different from the WT and TdflgE*.

Thus, the flagellar hooks of spirochetes undergo an unprecedented chemical cross-linking reaction that polymerizes the FlgE subunits and likely lends stability to the hook. The hook is known to be the most flexible component of the flagellar apparatus in other bacteria25, and covalent cross-linking of proteins is known to add structural stability26,27. A mechanically stable hook structure may be essential for motility of spirochetes because of the intimate interaction between the flagella and cell body in the periplasmic space. Covalent cross-linking is uncommon in bacteria, with known examples involving isopeptide and ester bonds catalyzed by sortases27, transglutaminases28, or the proteins themselves19,27. Most notably, proteins that self-catalyze their own covalent polymerization are quite rare, and the only known example is found in phage head proteins19. Although lysinoalanine occurs in some lantibiotics and as a byproduct of heating or preserving food or proteins, no specific function for this modification in proteins has been previously described21,29. The self-catalyzing nature of the FlgE cross-link could conceivably be exploited in protein engineering. Importantly, blocking lysinoalanine synthesis with agents reactive to dehydroalanine may offer a new avenue for antimicrobial development against spirochete infection.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

T. denticola ATCC 35405 was anaerobically grown in Oral Bacterial Growth Medium (OBGM) containing 10% heat-inactivated rabbit serum at 37°C23,30,31. For semisolid medium, 0.7% low-melting-point SeaPlaque agarose was incorporated into the OBGM medium, and the plates were poured after inoculating a bacterial suspension into the medium at 37°C24. Escherichia coli TOP10 strain (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used for routine plasmid constructions and preparations; an E. coli dam−/dcm− strain (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) was used to prepare unmethylated plasmids, and the E. coli BL21 Star™ (DE3) strain (Invitrogen) was used for preparing recombinant proteins. Unless noted, E. coli strains were cultured in lysogeny broth (LB) supplemented with appropriate concentrations of antibiotics. The fliK mutation, which results in PH production14, was originally constructed in ATCC strain 33520, and was transferred by electroporation and erythromycin selection into ATCC 35405. This strain is designated as TdFliK. Description, growth, and construction of the B. burgdorferi ΔfliK mutant, here named B. burgdorferi FliK, have been previously described12.

Preparation of rFlgE antiserum

To prepare a T. denticola FlgE antiserum, the entire open reading frame (orf) of TDE2768 (flgE) was PCR amplified using Platinum pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). The resulting amplicon was cloned into pET100/D-TOPO expression vector (Invitrogen) with an N-terminal 6×His (His6) fusion tag. The obtained plasmid (pTDE2768) was then transformed into E. coli B21 Star™ (DE3). The overexpression of flgE was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and the recombinant protein (rFlgE) was purified using Ni-NTA agarose under native conditions31. The final purified protein was dialyzed in tris (hydroxymethyl) amino methane (Tris) buffer (0.01 M Tris base, pH 8.0) at 4°C overnight. To produce an antiserum, rats were immunized with four injections of 0.25 mg/injection of rFlgE over 14 day intervals. The initial immunization was with Freund’s complete adjuvant, and the others with Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. Immunizations were conducted at General Biosciences Corporation, Brisbane, CA, which is a USDA approved Animal Research Facility. The facility meets and maintains high ethical and welfare standards in the area involving interactions with animals. The obtained antiserum was tested by immunoblotting.

Construction of E. coli strains producing mutant rFlgE proteins

E. coli strains were constructed bearing the following specific T. denticola flgE residue substitutions: K165A, K169A, N175A, C178A, N179A, and D181A. First, the full-length flgE gene (TDE2768) was PCR amplified, and then cloned into pGEM-T vector (Promega). All primers are listed in Supplementary Table 6. The cloned flgE gene was used as the template to construct the mutated genes. Below we describe how we constructed K165A as an example: The usage codon for K165 in the flgE gene was substituted with the one for Ala by PCR using the QuikChange® II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies). To express the altered protein, the entire open reading frame (orf) of flgE(K165A) was PCR amplified using Platinum pfx DNA polymerase and then cloned into the pET200/D-TOPO expression vector with an N-terminal 6×His (His6) fusion tag. A similar method was used to construct E. coli strains bearing the wild-type and K169A, N175A, C178A, N179A, and D181A substitutions; all substitutions were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

Isolation of rFlgE proteins for in vitro cross-linking

The WT rFlgE and its mutated versions were used to test for in vitro formation of HMWCs. Briefly, the above constructed flgE expression vectors were transformed into the E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) cells and grown in LB medium at 37°C. Once cells reached mid-logarithmic phase (O.D. of 0.4 to 0.5 at 600 nm), flgE expression was induced with IPTG for 4–6 hours. To obtain 14N and15N labeled rFlgE, E. coli cells were grown in M9 minimal media with either 14NH4Cl or 15NH4Cl (Sigma, 299251) supplemented with 171 mM NaCl32. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer (8M urea, 10 mM Tris, 100 mM sodium monobasic phosphate, pH 8). rFlgE was purified using a nickel agarose column (Qiagen) under denaturing conditions as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro synthesis of the HMWC and stability treatments

HMWCs were obtained by dialysis of T. denticola rFlgE (0.25 – 0.75 mg) at pH 8.5 in 40 mM Tris, 0.9% NaCl, and 1 M ammonium sulfate for 48 hour. These conditions were found to be optimal for FlgE in vitro cross-linking20. Renaturation of rFlgE presumably occurred during dialysis and HMWC formation. Furthermore, ammonium sulfate is known to promote in vitro hook assembly in other bacteria33. The stability of the PFs, PHs, and in vitro HMWC were determined. Samples were suspended in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0 and treated as follows: boiled 10 min; boiled in 1 M formic acid (FA) for 5 min followed by dialysis in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0; treated in 8 M urea for 12 hours at 4°C; treated with 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME) for 24 hours or 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 24 hours, 4°C.

Construction of T. denticola flgE mutant strains

To construct T. denticola strains with residue substitutions in flgE, we first constructed a deletion mutant. The entire flgE gene was inactivated by targeted mutagenesis mediated by allelic exchange as previously described34. The vector for the mutagenesis was constructed by multiple-step PCR. First, the flgE upstream region (Region 1), its downstream region (Region 2), and a modified gentamicin resistance gene (aacCm)34 were PCR amplified, respectively. Second, Region 1 and aacCm were linked by PCR. Third, the Region 1-aacCm and Region 2 fragments were fused by PCR. The final fragment Region 1-aacCm-Region 2 was cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector, yielding flgE::aacCm with the entire flgE gene being deleted and in-frame replaced with aacCm. The flgE::aacCm plasmid was purified from either the TOP10 or E. coli dam−/dcm− strain as previously described35. To inactivate flgE, 10 µg of linearized flgE::aacCm was transformed into the WT strain by electroporation. Mutants were selected on OBGM semisolid agar plates containing 20 µg/ml gentamicin. PCR analysis was used to determine if the allelic exchange flgE in these clones occurred as predicted34. The PCR results showed that the entire flgE gene in the mutant was deleted and replaced by aacCm as expected. The obtained mutant was referred to as ΔflgE.

By replacing the aacCm cassette in the ΔflgE mutant, we constructed mutants bearing residue substitutions in flgE. Specifically, we selected for either the WT or its five mutated versions of flgE, including K165A, K169A, C178A, N179A, and D181A. The vectors for allelic exchange were constructed by multiple-step PCR. First, the flgE upstream region (Region 1), its downstream region (Region 2), and an erythromycin resistance gene cassette (erm)36 were PCR amplified, respectively. An AvrII cut site was engineered at 3’ end of erm cassette. In the second step, Region 1 and erm were linked by PCR. In the third step, the Region 1-erm and Region 2 fragments were fused by PCR. The final fragment Region 1-erm-Region 2 was cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector, yielding the flgE::erm vector. The WT flgE and its mutated versions were PCR amplified with AvrII cut sites at both ends. The obtained PCR fragments were first cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector and then released with AvrII. The flgE fragments were then inserted into the flgE::erm vector at the AvrII restriction cut site, yielding Region 1-erm-flgE-Region 2 plasmids. To introduce the constructs into T. denticola cells, 10 µg of the unmethylated plasmids were transformed into ΔflgE by electroporation. The clones were selected on OBGM semisolid agar plates containing 50 µg/ml erythromycin. Mutant confirmation was obtained by PCR and DNA sequencing analysis. The results showed that the aacCm cassette was replaced either by the WT flgE or by the five mutated ones as expected. The obtained mutant strains are named as follows: TdK165A, TdK169A, TdC178A, TdN179A, and TdD181A. The deletion strain carrying the replaced WT flgE is named TdflgE*.

Isolation of PFs and PHs

PFs from the T. denticola WT and the PHs from the TdFliK mutant were purified using a procedure similar to that used to isolate these structures from B. burgdorferi12. Approximately 100 ml of late logarithmic phase wild-type or mutant cells at a density of 8 × 108 cells/ ml were centrifuged at 7,200 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C, and washed twice at this temperature in 30 ml 150 mM phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4. The cell pellet was then suspended in 30 ml 0.15 M Tris buffer (T buffer) at pH 6.8, centrifuged at 7,200 × g for 20 min 4°C, and re-suspended in 15 ml of T buffer. Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 2% and incubated for 30 min at 23°C. Approximately 20 ug/ml mutanolysin (Sigma) were added, incubated for 2 hours at 23°C while mixing, and then overnight at 4°C. The PFs or PHs were precipitated by the addition of 2 ml of 20% polyethylene glycol 8000 in 1 M NaCl, and centrifuged at 27,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant fluid was discarded, and the pellet was washed in 5 ml of T buffer, incubated for 30 min, then centrifuged as before. The pellet was resuspended and incubated for 1 hr in 0.1 M KCl/KOH, pH 11, with 50 mM sodium bicarbonate, 50 mM Tris, 0.5M sucrose and 0.1% Triton X-100 in a final volume of 5 ml. The PFs or PHs were then centrifuged at 80,000 × g for 45 minutes at 4°C. The PFs or PHs were washed by resuspending in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0 and centrifuging as before at 80,000×g. The final pellets containing PFs and PHs were resuspended in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0. PHs from the B. burgdorferi FliK mutant were purified using the identical procedure12.

SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis

SDS-PAGE was carried out using both the standard technique12,31,37, and the Bolt system (Life Technologies) which enhances separation of high molecular weight proteins. The Bolt system was used for all analyses except those in Figure 4. Approximately 5.0 µg protein (BioRad, Bradford) were loaded per lane, and electrophoresed in MOPS running buffer (pH 8.8) at 165 volts in 10% Bis Tris Plus polyacrylamide precast gels (Life Technologies). Molecular weight markers were obtained from BioRad or Life Technologies, and Imperial Stain (ThermoFisher) was used to stain gels. For western blotting, 0.25–0.50 µg of total protein were loaded per lane, electrophoresed, and transferred to polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Immunoblots were probed with rat polyclonal antibody against T. denticola rFlgE and secondary horse-radish-peroxidase (HRP) labelled polyclonal goat anti-rat antibodies. T. denticola FlaB was detected using anti-FlaB rabbit polyclonal antiserum immunized against T. phagedenis FlaB38, which reacts with T. denticola FlaB proteins14,38, and HRP donkey anti-rabbit antibodies. Mouse antisera to T. denticola thiamine binding protein A (pBA) have been previously described31. An enhanced chemiluminescent detection system (ThermoFisher) was used to assay for immunoreactivity. For densitometry analysis, protein gels were scanned with a BioRad Chemi-Doc Touch Imaging System. Data were entered into BioRad Image Lab Version 5.2.1 software for analysis. Except as noted, at least three gels or blots were analyzed, and representative images are shown.

Motion tracking assays

For the motion tracking analysis, 100 µl of mid-logarithmic-phase T. denticola cultures was first diluted (1:1) in fresh OBGM, and then 10 µl were mixed with an equal volume of 2% methylcellulose (Sigma, MC4000). Cells were videotaped and tracked using a computer-based bacterial tracking system and the mean cell velocity (µm/second) was calculated as previously described39. The significance of the difference between different strains was evaluated with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values < 0.01 were considered significant.

Lysinoalanine analysis

The HMWC and the monomer were partially purified using agarose gel-electrophoresis40. The in vitro formed HMWC was dialyzed against 90 mM Tris, 90 mM Borate, pH 8.5, treated with Bolt or standard sample buffer for 5 min, 70°C, and electrophoresed in 2% agarose flanked by Dual Color marker proteins. Based on the position of molecular weight markers, regions corresponding to monomer (~50 kDa) and HMWCs (~150 kDa, and ≥250 kDa) were excised and electroeluted. Monomeric rFlgE from the gel was isolated using this same procedure. Aliquots of electroeluted proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and submitted for amino acid analysis. Purified lysinoalanine (Indofine Chemical Co. NJ) was used to determine the retention time and quantitate lysinoalanine. Levels of lysinoalanine were normalized to Gly, Ala, Tyr.

Mass-spectrometry analysis

Sequence grade acetonitrile (ACN), Optima grade water, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and FA were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Ammonium biocarbonate, iodoacetamide (IAM), DTT, Tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Modified porcine trypsin was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). The rest of the chemical reagents, unless otherwise noted, were obtained from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). The monomer and cross-linked multimer of T. denticola and B. burgdorferi FlgE protein were separated on an SDS gel as described above. The protein bands were cut into ~1 mm cubes and subjected to in-gel digestion followed by extraction of the tryptic peptides as reported previously41. The excised gel pieces were washed consecutively in 200 µl distilled water, 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate (Ambic)/ACN [1:1] and then ACN. The gel pieces were reduced with 70 µl of 10 mM DTT in 100 mM Ambic for 1 hr at 56 °C and then alkylated with 100 µl of 55 mM Iodoacetamide in 100 mM Ambic at room temperature in the dark for 60 min. After wash steps as described above, the gel slices were dried and rehydrated with 50 µl trypsin in 50 mM Ambic, 10% ACN (20 ng/µL) at 37 °C for 16 hrs. The digested peptides were extracted twice with 70 µl of 50% ACN, 5% FA and once with 70 µl of 90% ACN, 5% FA. Extracts from each sample were combined and evaporated to dryness by a Speedvac SC110 (Thermo Savant, Milford, MA). The sample was reconstituted in 20 µl of 0.1% FA with 2% ACN prior to nanoLC UV-vis-MS/MS analysis. For peptide mapping by nanoLC/MS/MS analysis, the in-gel tryptic digests were reconstituted in 20 µl of 0.5% FA for nanoLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis, which was carried out by a LTQ-Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) equipped with a “CorConneX” nano ion source device (CorSolutions LLC, Ithaca, NY). The Orbitrap was interfaced with a Dionex UltiMate3000RSLCnano system (Thermo, Sunnyvale, CA). The gel extracted peptide samples (5 µl) were injected onto a PepMap C18 trap column-nano Viper (5 µm, 100 µm × 2 cm, Thermo) at 20 µl/min flow rate for on-line desalting and then separated on a PepMap C18 RP nano column (3 µm, 75 µm × 15 cm, Thermo) which was installed in the nano device with a 10-µm spray emitter (NewObjective, Woburn, MA). The Orbitrap calibration and nanoLC-MS/MS operation were as previously described42. The peptides were eluted with a 90 min gradient of 5% to 38% ACN in 0.1% FA at a flow rate of 300 nl/min, followed by a 5-min ramping to 95% ACN-0.1% FA and a 7-min hold at 95% ACN-0.1% FA. The Orbitrap Elite was operated in positive ion mode with nano spray voltage set at 1.5 kV and source temperature at 250°C. In an initial screening experiment for cross-linked peptides, in-gel digests of T. denticola rFlgE monomer band and multimer bands were analyzed by a nanoLC UV-vis-MS/MS approach in which UV 214nm wavelength in the nanoLC setting was monitored along with online Orbitrap MS and MS/MS detection, specifically focusing on the different UV-vis-MS chromtograph profiles between monomer and multimer samples for possible cross-linked tryptic peptides. This analytical approach and setting was successfully tested and calibrated to the injection of 2 pmol bovine serum albumin tryptic digest to establish an 11 min delay time for MS signal compared to UV signals prior to analysis for FlgE proteins. The Orbitrap Elite was operated in parallel data-dependent acquisition (DDA) under FT-IT mode using an FT mass analyzer for one MS survey scan from m/z 375 to 1800 with a resolving power of 120,000 (fwhm at m/z 400) followed by MS/MS scans on the top 15 most intense peaks with multiple charged ions above a threshold ion count of 10,000 in LTQ mass analyzer. Internal calibration using the background ion signal at m/z 445.120025 as a lock mass or external calibration for FT mass analyzer was performed. Dynamic exclusion parameters and normalized collisional energy were set the same as previously described42,43. All data were acquired under Xcalibur 2.2 operation software (Thermo-Fisher Scientific). Data is representative of 3 analyzed peptides.

For high-resolution mass fragments from MS/MS data (Supplementary Fig. 4), trypsin digested in vitro formed HMWCs and monomer peptides were analyzed by LC-ESI MS using a QTrap5500 (AB Sciex Toronto, Canada) at Protea Biosciences, Inc. Peptides were separated at 35uC on a Kinetex 10062.1 mm C18 column on a Shimadzu LC-20AD HPLC (Tokyo, Japan) using a 120-min gradient. The mass range acquired (m/z) was 100–1000, and the three most intense multiply charged ions with ion intensities above 50,000 in each MS scan were subjected to MS/MS12.

For data analysis, MS and MS/MS raw spectra were processed using Proteome Discoverer 1.4 (PD1.4, Thermo) and output as MGF files by PD1.4 for subsequent database search with the Mascot searching engine (2.3.02, Matrix Science, Boston, MA) against Trembl database (1,371,358 entries downloaded on 06/23/2011) with a taxonomy of “Other Bacteria”. The Mascot search was performed by allowing for two-missed trypsin cleavage sites. The peptide tolerance was set to 10 ppm and MS/MS tolerance was set to 0.8 Da. Variable modifications on methionine oxidation, carbamidomethyl modification of cysteine and deamindation of asparagine and glutamine, were monitored. The peptides with low confident score <25 under 95% CI, as defined by Mascot, were filtered out and the remaining peptides were considered for the peptide identification with modifications. All MS/MS spectra for peptides containing the cross-linked tryptic peptide (148–182) identified from initial database searching were manually inspected and validated using both Mascot 2.3 and Xcalibur 2.2 software. All unique target peptides identified in the Td rFlgE, Td PH and Bb PH samples and their corresponding sequence coverage are given in Supplementary Tables 3–5. The MS/MS spectra for mixed 14N-15N labeled cross-linked peptides and BME modified cross-linked peptide were manually inspected and confirmed. The extraction ion chromatograms of each modified peptide ion with different charge states were obtained based on precursor ion m/z with mass tolerance of 5 ppm in Xcalibur software.

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM)

Aliquots of 5 µl of purified PFs and PHs were placed on freshly glow-discharged holey carbon grids (Quantifoil Cu R2/2, 200 mesh). The grids were blotted with filter paper and rapidly frozen in liquid ethane, using a gravity-driven plunger apparatus. Cryo-EM samples were imaged on a 300kV electron microscope (FEI Polara). Low dose images were recorded on a direct electron detector (Gatan K2-Summit) at a magnification of ×15,500 (yielding an effective pixel size of 2.6Å). A total dose of 20 electrons per Å2 was divided into 30 frames. The frames were aligned and summed together to generate drift-corrected cryo-EM images. For each strain, we took at least twenty cryo-EM images. One representative image from each strain was shown as part of the results. Cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) was utilized to study the hook structures in intact cells as previously described12,13,17,19. Briefly, bacterial cultures were mixed with 10 nm gold markers and frozen rapidly in liquid ethane. Low dose tilt series were recorded at a magnification of ×9,400 (yielding an effective pixel size of 4.6Å). Three to five tomographic reconstructions were generated from the cell tips of each strain with a total of 19 reconstructions from the WT, and TdK165A, TdC178A, TdN179A mutants.

Structural modeling of FlgE Hook structure

The spirochete hook model was constructed from many copies of a Td FlgE D1 and D2 domain homology model based on the atomic coordinates of the S. enterica FlgE structures (PDB: code 1WLG) and derived by Swiss-Model. The hook polymer was produced by applying to the D1D2 model the symmetry operations determined from the electron microscopy structure of the S. enterica hook (PDB code: 3A69).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health R01-DE023432 (N.C, M.M., C.L.), R01 GM064664 (B.C.), R01-AI087946 (J.L.), and R01-DE023080 and R01-AI078958 (C. L). J.L. was also supported by AU-1714 from the Welch Foundation. We thank B. Bachert, M. Barbier, R. Duda, R. Hendrix, D. McNitt, S. Norris, R. Silversmith, and R. Sircar for suggestions, technical assistance, and support. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Footnotes

Author Contribution: N.C., M.M. designed the project. B.C., N.C., C.L, J.L., M.M. wrote the manuscript. P.C., N.C., B.C., J.H, M.J., C.L., J.L., K.M., M.M. designed experiments. J.B., A.C., J.L., K.M., M.M., M.J., M.L., S.Z. carried out experiments.

Supplemental videos are available in the online version of the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Paster BJ. In: Bergey's Manuel of Systematic Bacteriology. Krieg NR, et al., editors. Vol. 4. Springer Publishing Company; 2011. pp. 471–566. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sultan SZ, et al. Motility is crucial for the infectious life cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 2013;81:2012–2021. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01228-12. doi:IAI.01228-12 [pii];10.1128/IAI.01228-12 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li C, Xu H, Zhang K, Liang FT. Inactivation of a putative flagellar motor switch protein FliG1 prevents Borrelia burgdorferi from swimming in highly viscous media and blocks its infectivity. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;75:1563–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sze CW, Zhang K, Kariu T, Pal U, Li C. Borrelia burgdorferi needs chemotaxis to establish infection in mammals and to accomplish its enzootic cycle. Infect. Immun. 2012;80:2485–2492. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00145-12. doi:IAI.00145-12 [pii];10.1128/IAI.00145-12 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert A, et al. FlaA Proteins in Leptospira interrogans are essential for motility and virulence but are not required for formation of the flagellum sheath. Infect. Immun. 2012;80:2019–2025. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00131-12. doi:IAI.00131-12 [pii];10.1128/IAI.00131-12 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao S, et al. Inactivation of the fliY gene encoding a flagellar motor switch protein attenuates mobility and virulence of Leptospira interrogans strain Lai. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sultan SZ, et al. Motor rotation is essential for the formation of the periplasmic flagellar ribbon, cellular morphology, and Borrelia burgdorferi persistence within Ixodes scapularis tick and murine hosts. Infect. Immun. 2015;83:1765–1777. doi: 10.1128/IAI.03097-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charon NW, Goldstein SF. Genetics of motility and chemotaxis of a fascinating group of bacteria: The spirochetes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2002;36:47–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.041602.134359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charon NW, et al. The unique paradigm of spirochete motility. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;66:349–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolgemuth CW. Flagellar motility of the pathogenic spirochetes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015;46:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wunder EA, et al. A novel flagellar sheath protein, FcpA, determines filament coiling, translational motility and virulence for the Leptospira spirochete. Mol Microbiol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/mmi.13403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller KA, et al. Initial characterization of the FlgE hook high molecular weight complex of Borrelia burgdorferi. PloS one. 2014;9:e98338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Limberger RJ, Slivienski LL, Samsonoff WA. Genetic and biochemical analysis of the flagellar hook of Treponema phagedenis. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:3631–3637. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3631-3637.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Limberger RJ, Slivienski LL, Izard J, Samsonoff WA. Insertional inactivation of Treponema denticola tap1 results in a nonmotile mutant with elongated flagellar hooks. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:3743–3750. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3743-3750.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi B, Limberger RJ, Kuramitsu HK. Complementation of a Treponema denticola flgE mutant with a novel coumermycin A1-resistant T. denticola shuttle vector system. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:2233–2237. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2233-2237.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Limberger RJ, Slivienski LL, El-Afandi MCT, Dantuono LA. Organization, transcription, and expression of the 5' region of the fla operon of Treponema phagedenis and Treponema pallidum. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:4628–4634. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4628-4634.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sal MS, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi uniquely regulates its motility genes and has an intricate flagellar hook-basal body structure. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:1912–1921. doi: 10.1128/JB.01421-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones CJ, Macnab RM, Okino H, Aizawa S. Stoichiometric analysis of the flagellar hook-(basal-body) complex of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;212:377–387. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popa MP, McKelvey TA, Hempel J, Hendrix RW. Bacteriophage HK97 structure: wholesale covalent cross-linking between the major head shell subunits. J. Virol. 1991;65:3227–3237. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3227-3237.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller KA. Ph.D. thesis. West Virginia University; 2013. Characterization of the Unique Flagellar Hook Structure of the Spirochetes Borrelia burgdorferi and Treponema denticola. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman M. Chemistry, biochemistry, nutrition, and microbiology of lysinoalanine, lanthionine, and histidinoalanine in food and other proteins. y. 1999;47:1295–1319. doi: 10.1021/jf981000+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujii T, Kato T, Namba K. Specific arrangement of alpha-helical coiled coils in the core domain of the bacterial flagellar hook for the universal joint function. Structure. 2009;17:1485–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruby JD, et al. Relationship of Treponema denticola periplasmic flagella to irregular cell morphology. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:1628–1635. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1628-1635.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H, Ruby J, Charon N, Kuramitsu H. Gene inactivation in the oral spirochete Treponema denticola: construction of a flgE mutant. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:3664–3667. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3664-3667.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Son K, Guasto JS, Stocker R. Bacteria can exploit a flagellar buckling instability to change direction. Nature Physics. 2013;9:494–498. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duda RL, et al. Structure and energetics of encapsidated DNA in bacteriophage HK97 studied by scanning calorimetry and cryo-electron microscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;391:471–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker EN, Squire CJ, Young PG. Self-generated covalent cross-links in the cell-surface adhesins of Gram-positive bacteria. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015;43:787–794. doi: 10.1042/BST20150066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monroe A, Setlow P. Localization of the transglutaminase cross-linking sites in the Bacillus subtilis spore coat protein GerQ. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:7609–7616. doi: 10.1128/JB.01116-06. doi:JB.01116-06 [pii];10.1128/JB.01116-06 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okesli A, Cooper LE, Fogle EJ, van der Donk WA. Nine post-translational modifications during the biosynthesis of cinnamycin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:13753–13760. doi: 10.1021/ja205783f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orth R, O'Brien-Simpson N, Dashper S, Walsh K, Reynolds E. An efficient method for enumerating oral spirochetes using flow cytometry. J. Microbiol. Meth. 2010;80:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bian J, Shen H, Tu Y, Yu A, Li C. The riboswitch regulates a thiamine pyrophosphate ABC transporter of the oral spirochete Treponema denticola. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:3912–3922. doi: 10.1128/JB.00386-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McIntosh LP, et al. Proton NMR measurements of bacteriophage T4 lysozyme aided by 15N isotopic labeling: structural and dynamic studies of larger proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1987;84:1244–1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vonderviszt F, Zavodszky P, Ishimura M, Uedaira H, Namba K. Structural organization and assembly of flagellar hook protein from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;251:520–532. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0453. doi:S0022-2836(85)70453-6 [pii];10.1006/jmbi.1995.0453 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bian J, Fenno JC, Li C. Developing a modified gentamicin resistance cassette for genetic manipulation of the oral spirochete Treponema denticola. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.1128/AEM.07461-11. doi:AEM.07461-11 [pii];10.1128/AEM.07461-11 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bian J, Li C. Disruption of a type II endonuclease (TDE0911) enables Treponema denticola ATCC 35405 to accept an unmethylated shuttle vector. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:4573–4578. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00417-11. doi:AEM.00417-11 [pii];10.1128/AEM.00417-11 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goetting-Minesky MP, Fenno JC. A simplified erythromycin resistance cassette for Treponema denticola mutagenesis. J. Microbiol. Meth. 2010;83:66–68. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.07.020. doi:S0167-7012(10)00251-4 [pii];10.1016/j.mimet.2010.07.020 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Limberger RJ, Charon NW. Antiserum to the 33,000-dalton periplasmic-flagellum protein of "Treponema phagedenis" reacts with other treponemes and Spirochaeta aurantia. J. Bacteriol. 1986;168:1030–1032. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.1030-1032.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bian J, Liu X, Cheng YQ, Li C. Inactivation of cyclic Di-GMP binding protein TDE0214 affects the motility, biofilm formation, and virulence of Treponema denticola. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:3897–3905. doi: 10.1128/JB.00610-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gels. 2015 < http://bio.lonza.com/uploads/tx_mwaxmarketingmaterial/Lonza_BenchGuides_SourceBook_Section_XIII_-_Protein_Separation_in_Agarose_Gels.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Y, Thannhauser TW, Li L, Zhang S. Development of an integrated approach for evaluation of 2-D gel image analysis: impact of multiple proteins in single spots on comparative proteomics in conventional 2-D gel/MALDI workflow. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:2080–2094. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Y, et al. Evaluation of different multidimensional LC-MS/MS pipelines for isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ)-based proteomic analysis of potato tubers in response to cold storage. J. Proteome Res. 2011;10:4647–4660. doi: 10.1021/pr200455s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hochrainer K, Racchumi G, Zhang S, Iadecola C, Anrather J. Monoubiquitination of nuclear RelA negatively regulates NF-kappaB activity independent of proteasomal degradation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012;69:2057–2073. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0912-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.