Abstract

Mycolic acids are essential components of the mycobacterial cell envelope, and their biosynthetic pathway is a well known source of antituberculous drug targets. Among the promising new targets in the pathway, FadD32 is an essential enzyme required for the activation of the long meromycolic chain of mycolic acids and is essential for mycobacterial growth. Following the in-depth biochemical, biophysical, and structural characterization of FadD32, we investigated its putative regulation via post-translational modifications. Comparison of the fatty acyl-AMP ligase activity between phosphorylated and dephosphorylated FadD32 isoforms showed that the native protein is phosphorylated by serine/threonine protein kinases and that this phosphorylation induced a significant loss of activity. Mass spectrometry analysis of the native protein confirmed the post-translational modifications and identified Thr-552 as the phosphosite. Phosphoablative and phosphomimetic FadD32 mutant proteins confirmed both the position and the importance of the modification and its correlation with the negative regulation of FadD32 activity. Investigation of the mycolic acid condensation reaction catalyzed by Pks13, involving FadD32 as a partner, showed that FadD32 phosphorylation also impacts the condensation activity. Altogether, our results bring to light FadD32 phosphorylation by serine/threonine protein kinases and its correlation with the enzyme-negative regulation, thus shedding a new horizon on the mycolic acid biosynthesis modulation and possible inhibition strategies for this promising drug target.

Keywords: cell wall, lipid metabolism, mycobacteria, post-translational modification (PTM), protein phosphorylation

Introduction

Mycobacteria are unique in that they produce a remarkable collection of lipids with exotic structures such as the very complex long-chain mycolic acids (MAs),7 which are exceptionally long (the majority ranging from C70 to C90) α-branched and β-hydroxylated fatty acids (1). MAs are the main constituents of the outer membrane and a critical player in both architecture and permeability of the mycobacterial cell envelope (2, 3). Their biosynthesis is essential for Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival and thereby provides opportunities to target numerous enzymes from this metabolic pathway (1).

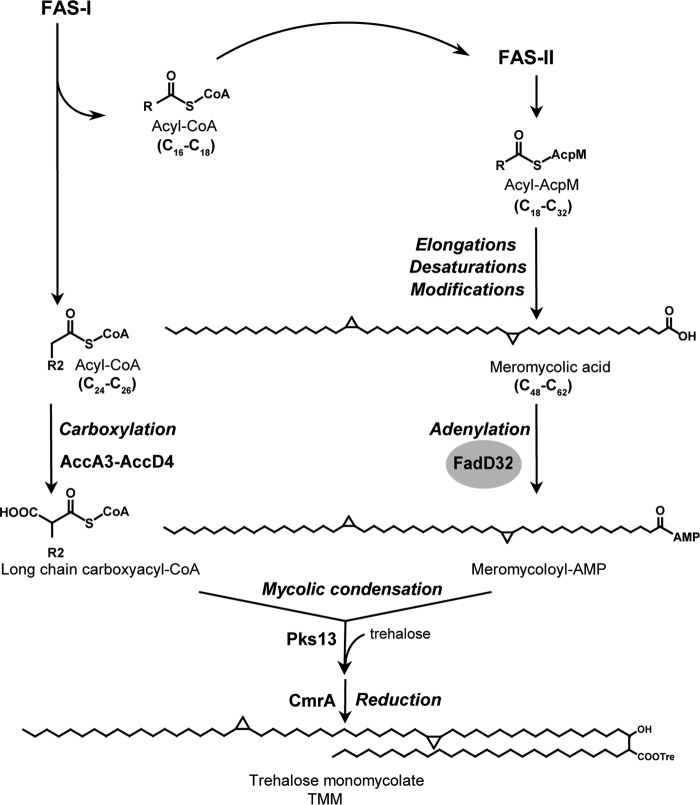

The synthesis of MAs requires the combined action of fatty-acid synthases (FASs) and polyketide synthases (PKSs). It involves both FAS-I (for de novo synthesis) and FAS-II (for elongation) and the action of Pks13 to achieve the final condensation between two activated fatty acids (Fig. 1). A specific subclass of the FadD (fatty acid degradation) family of enzymes establishes the connection between FASs and PKSs by providing the activated fatty acyl adenylates to their cognate PKSs (4). The M. tuberculosis genome contains 34 fadD genes encoding FadD proteins that are grouped into the following two subclasses: fatty acyl-CoA ligases involved in lipid degradation and fatty acyl-AMP ligases (FAALs) dedicated to lipid biosynthesis (5). FAALs activate and transfer fatty acids to PKSs for further chain extension to provide most of the highly specialized M. tuberculosis lipids. Interestingly, many of the M. tuberculosis FadD proteins represent potential drug targets due to their confirmed essentiality or requirement for virulence (6).

FIGURE 1.

Mycolic acid condensation reaction involves meromycolic acid activation by FadD32. The biosynthetic pathway of mycolic acid implicates the de novo synthesis and elongation of fatty acids operated by the mycobacterial fatty-acid synthases FAS-I and FAS-II, respectively. The FAS-II synthase products undergo further elongations, desaturations, and modifications differentiated by a family of methyltransferases to yield the very long-chain meromycolic chains. The meromycolic acid is activated into meromycoloyl-AMP by FadD32 and condensed with carboxylated acyl-CoA activated by the acyl-CoA carboxylase ACCase (AccA3–AccD4) to yield α-alkyl β-ketoester of trehalose that is reduced by CmrA to form the mature mycolic acid (trehalose monomycolate, TMM). R and R2 are long hydrocarbon chains.

One of the most extensively studied FAALs is FAAL32, named FadD32, and is required for MA biosynthesis. FadD32 (Rv3801c) is unique as it activates the very long-chain meromycolic acid (C48–C62) and subsequently assists the transfer of the meromycoloyl chain onto the N-terminal acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain of the condensing enzyme Pks13, revealing an additional acyl-ACP ligase function of this FAAL (7–9). The condensation of the activated meromycolic acid with a C24–C26 fatty acid activated by the AccD4-containing acyl-CoA carboxylase yields, upon reduction, mature mycolic acids (Fig. 1) (10, 11). Noteworthy, the fadD32-pks13-accD4 operon is present in all mycobacteria sequenced to date and was proved to be essential for mycobacterial viability (10, 11). Conditional expression of fadD32 has confirmed its essentiality for the growth of M. tuberculosis (12, 13), Mycobacterium smegmatis (11), and Mycobacterium abscessus (14), whereas knockdown studies established that the fadD32 operon was a vulnerable target (15). Consequently, FadD32 represents a particularly attractive drug target.

M. tuberculosis also possesses 11 serine/threonine protein kinases (STPKs) that regulate, by phosphorylation, many intracellular metabolic processes (16, 17). Among these, several key enzymes of the MA biosynthesis pathway have been reported to be phosphorylated, thus regulating their respective enzymatic activity (18, 19). These include essential enzymes of the M. tuberculosis FAS-II system, namely KasA, InhA, and MabA and the dehydratases HadAB and HadBC. In addition, the phosphorylation of the mycolic acid cyclopropane synthase PcaA, an enzyme involved in the modification of MAs, inhibits MA cyclopropanation, thereby modulating mycolic acid composition and intracellular survival of mycobacteria (20). The proportion of phosphorylated HadAB and HadBC has also been shown to clearly increase at the stationary growth phase, consistent with a reduced MA synthesis and suggesting that mycobacteria may shut down meromycolic acid chain production during this phase (19).

Therefore, the essentiality of FadD32 in the biosynthesis of MAs and its significant role as a promising drug target prompted us to investigate its regulation by post-translational modification (PTM) through phosphorylation by STPKs. Here, we show for the first time that FadD32 is phosphorylated by STPKs, resulting in a significant decrease of both its FAAL activity and the condensation activity leading to MAs, in which FadD32 is an essential partner of the condensing enzyme Pks13.

Results

FadD32 Is Phosphorylated in Vitro by Mycobacterial Ser/Thr Protein Kinases

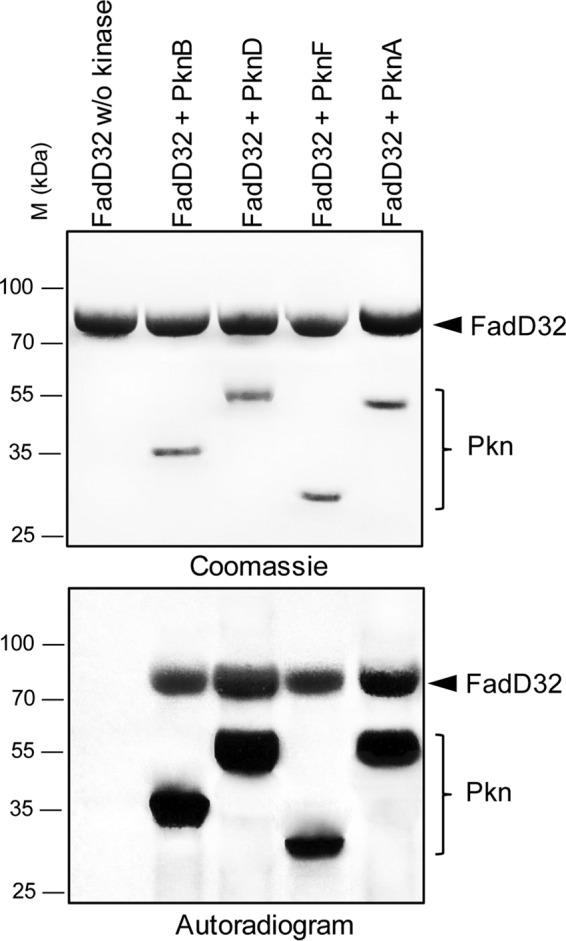

Within the MA biosynthetic pathway, shown to possess several key enzymes regulated by phosphorylation (19, 21–23), we investigated whether the meromycolic chain activation step catalyzed by the FAAL FadD32 from M. tuberculosis (MtbFadD32, FadD32) was also regulated by phosphorylation. Interestingly, a global phosphoproteomic study in M. tuberculosis H37Rv, where more than 300 M. tuberculosis phosphoproteins were identified, postulated that FadD32 phosphorylation could be performed preferentially by PknA, -B, -D, and -F (24). Accordingly, the soluble kinase domains of these transmembrane kinases from M. tuberculosis were expressed as GST-tagged (PknA and PknD) or His-tagged (PknB and PknF) fusion proteins and were purified from Escherichia coli as reported earlier (25). The different kinases were incubated with MtbFadD32 expressed in E. coli and [γ-33P]ATP and resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the phosphorylation status of FadD32 was analyzed by autoradiography. The presence of an intense radioactive signal indicated that FadD32 was phosphorylated by the four STPKs tested (Fig. 2). As expected, no radioactive band was observed in the absence of kinase. Therefore, FadD32 is able to interact with several STPKs, as shown previously for other M. tuberculosis STPK substrates (19, 20, 23, 26–28), suggesting that these M. tuberculosis enzymes may be regulated by multiple signals. Moreover, our results are consistent with the global phosphoproteomic study in M. tuberculosis H37Rv (24) and confirm that FadD32 could be regulated by Ser/Thr phosphorylation in vitro.

FIGURE 2.

In vitro phosphorylation of M. tuberculosis FadD32 by STPKs. The soluble domains of four recombinant M. tuberculosis STPKs were expressed and purified as GST-tagged (PknA and PknD) or His-tagged (PknB and PknF) fusion proteins and incubated with purified His-tagged FadD32 and [γ-33P]ATP. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, stained with Coomassie Blue (upper panel), and visualized by autoradiography after overnight exposure (lower panel). Upper bands reflect the phosphorylation signal of FadD32, and the lower bands correspond to the autophosphorylation activity of each kinase. M, molecular mass markers.

Phosphorylation of FadD32 Negatively Regulates Its Fatty Acyl-AMP Ligase Activity

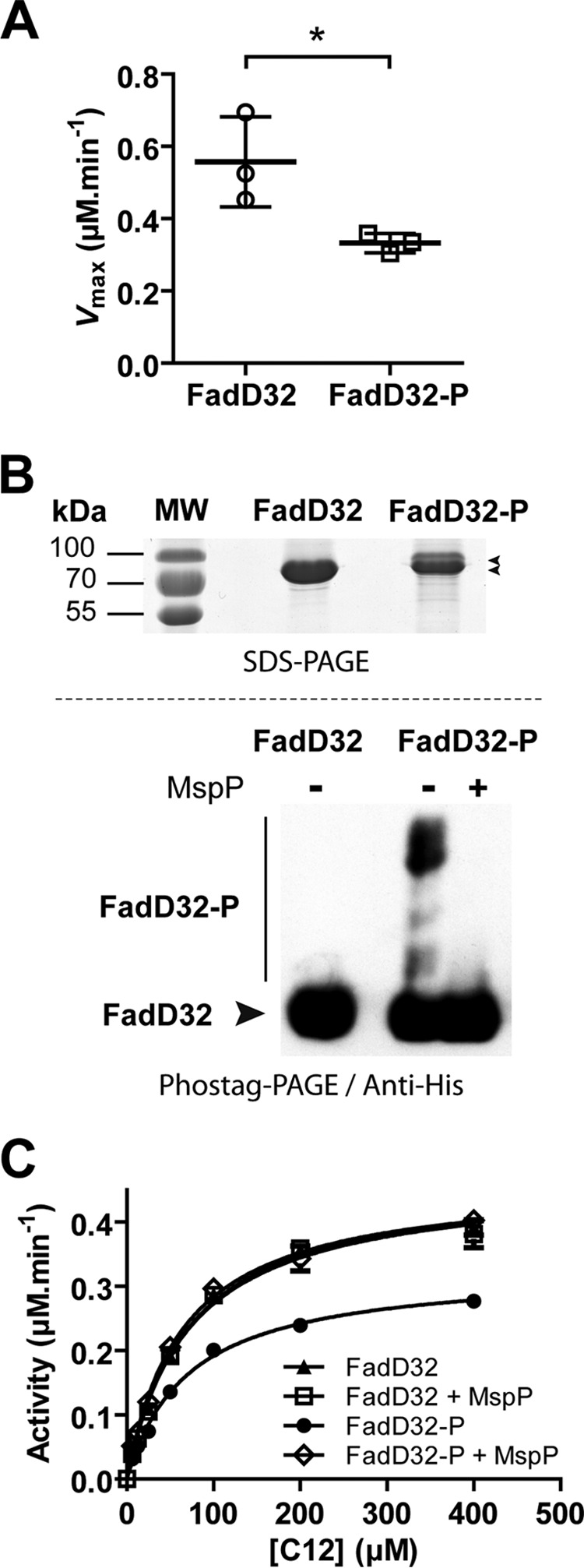

To determine the role of the phosphorylation on FadD32 activity, it was critical to obtain a protein population enriched in phosphorylated FadD32 (FadD32-P). This enrichment was achieved by co-expression of FadD32 and PknB in E. coli. FadD32 was either expressed alone or co-expressed with PknB in the E. coli strain BL21(DE3) Star. Phosphorylated FadD32-P was purified from E. coli co-expressing FadD32 and PknB (pDuet_pknB), a system reported to produce high amounts of phosphoprotein (29). The resulting FadD32-P protein was tested for its FAAL activity using the FadD32-inorganic pyrophosphatase-coupled assay (30) and compared with the non-phosphorylated FadD32 (Fig. 3A). Remarkably, when FadD32 and the kinase were co-expressed (FadD32-P), a significant and reproducible loss of activity (−40%) was measured compared with the protein solely expressed in E. coli (FadD32) (Fig. 3A). These results indicate that STPK-mediated phosphorylation impairs FadD32 activity, at least in vitro.

FIGURE 3.

FadD32 phosphoisoforms and effect of PknB phosphorylation on FAAL activity. The FadD32 protein was expressed and purified in E. coli either solely (FadD32) or co-expressed with PknB (FadD32-P). A, FAAL activity of non-phosphorylated (FadD32) and phosphorylated (FadD32-P) forms was assessed spectrophotometrically in the inorganic pyrophosphate coupled assay (as described under “Experimental Procedures”). Scatter plots showing maximum velocity Vmax for lauric acid (C12), as determined using non-linear regression to fit the Michaelis-Menten equation to the data (Prism 5.04). Values are representative of three sets of experiments with independent protein preparations ± S.D. The p value = 0.038 was calculated by Student's t test. B, detection of FadD32 phosphoisoforms. Two μg of purified His-tagged FadD32 derivatives were analyzed by SDS-PAGE after staining with Instant Blue (upper panel). Phostag SDS-PAGE separation of 4 μg of purified His-tagged FadD32 derivatives was followed by immunoblotting with anti-polyhistidine antibodies (lower panel). The FadD32-P was pretreated or not with M. smegmatis protein phosphatase MspP as indicated. C, FAAL activity of phosphorylated FadD32 (FadD32-P) following dephosphorylation by MspP; non-phosphorylated FadD32 was treated with MspP as a control. Michaelis-Menten non-linear regression curves are displayed using C12 as substrate; values are means ± S.E. of four experimental replicates.

Phosphorylation-dependent FadD32 Loss of Activity Is Reversed by the Mycobacterial Phosphatase MspP

To confirm that the decrease of FadD32 activity was due to its phosphorylation status, we investigated whether FadD32 phosphorylation was reversible using the mycobacterial serine/threonine protein phosphatase MspP (31), commonly used to specifically dephosphorylate STPK substrates (32, 33). First, migration on SDS-PAGE allowed the detection of a shifted band that would correspond to the FadD32-phosphorylated isoform(s) (Fig. 3B, upper panel). To ascertain this, we used the Phostag gel-shift assay strategy (34) to reveal FadD32-phosphorylated isoforms, further detected by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 3B (lower panel), the FadD32-P protein presented a significant band shift compared with the non-phosphorylated FadD32, with putatively several phosphorylation states. Then, we investigated the dephosphorylation of FadD32-P by the mycobacterial protein phosphatase MspP from M. smegmatis. Significantly, incubation with the protein phosphatase MspP totally abolished the band shift, thus confirming that FadD32 is phosphorylated upon co-expression with PknB.

To definitely establish that the observed decrease of FadD32 activity was specifically due to its phosphorylation, we performed a FAAL assay in the absence or presence of MspP. FadD32-P was incubated with MspP in a phosphatase reaction assay specially optimized to be compatible with subsequent FadD32 assays. Dephosphorylation of FadD32-P by MspP relieved inhibition and allowed recovery of most of FAAL activity (Fig. 3C). These results confirmed that FadD32 is phosphorylated by STPK and that this phosphorylation could be reversed by the action of the specific mycobacterial phosphatase MspP. More importantly, these data clearly establish that phosphorylation of FadD32 was indeed responsible for the observed decrease in FAAL activity, at least in vitro.

FadD32 Activity in Mycobacteria

All biochemical characterizations of MtbFadD32 were performed so far with the recombinant protein produced in E. coli (5, 8, 30, 35), thus lacking any phosphorylation as E. coli does not possess any canonical STPK. Because production of M. tuberculosis proteins in E. coli often results in insoluble forms, recent studies using the non-pathogenic M. smegmatis strain as an alternative to E. coli represented real progress by favoring proper folding (36). In addition, production of FadD32 in this mycobacterial surrogate host offers the possibility to investigate the role of post-translational modifications, as reported for other proteins of the MA pathway (KasA/B, MabA/InhA, HadAB/BC, etc.) (19, 21–23).

M. smegmatis mc2155 possesses nine STPKs, namely PknA, -B, -D–H, -K, and -L, instead of 11 in M. tuberculosis, and it is widely used as a surrogate host for phosphorylation studies (19, 28). First attempts of FadD32 expression and purification in M. smegmatis led to the recovery of low yields of protein, co-eluting with an ∼60-kDa protein, identified as the mycobacterial GroEL1 chaperone by mass spectrometry. This co-elution of GroEL1 with weakly expressed His-tagged proteins in M. smegmatis has previously been reported (36), likely because of a histidine stretch at the C terminus of GroEL1, facilitating its co-elution with His-tagged proteins during the metal ion affinity chromatography step. For further expression and purification of FadD32, we therefore used the modified mc2155 GroEL1ΔC strain where GroEL1 His residues at the C terminus were mutated (36).

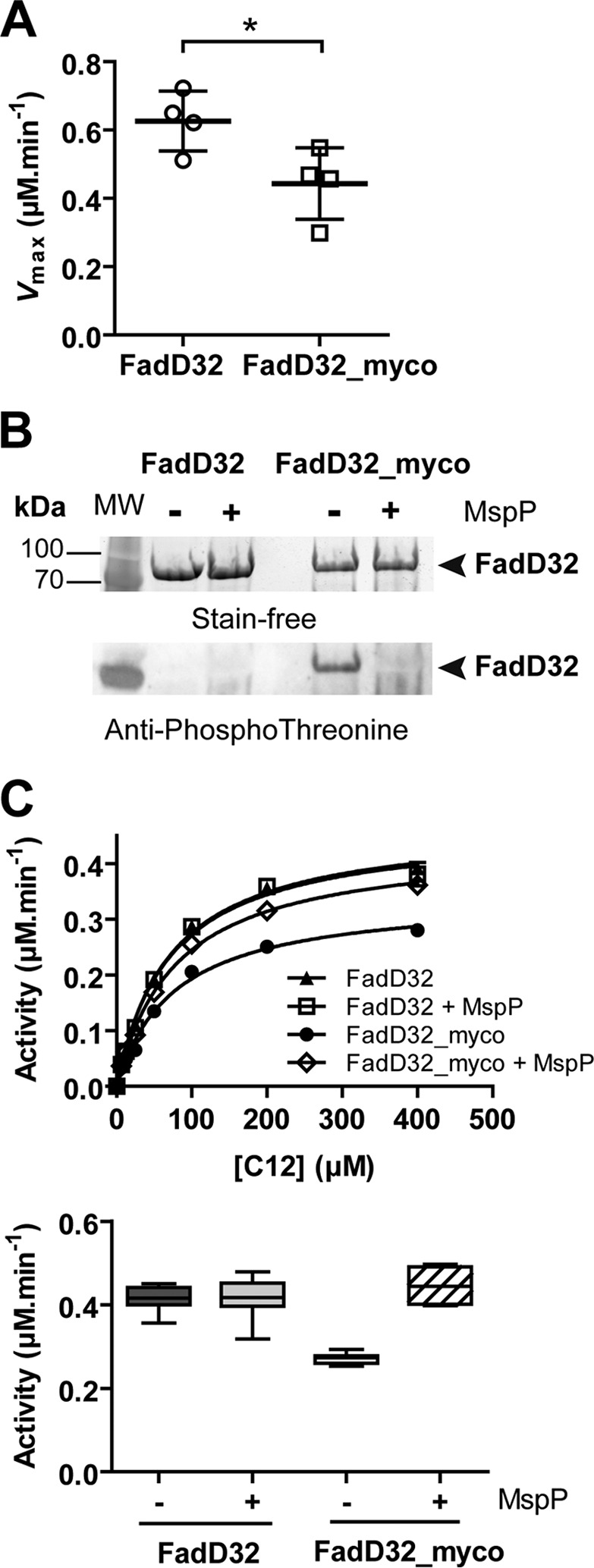

The MtbFadD32 protein was therefore expressed and purified either in the M. smegmatis mc2155 GroEL1ΔC strain, using a lac-inducible mycobacterial vector, or in E. coli. Then, MtbFadD32 proteins produced both in mycobacteria and E. coli were purified and compared for their fatty acyl-AMP ligase activities. Analysis of the apparent kinetic parameters for both proteins, using lauric acid (C12) as substrate, showed a significant and reproducible decrease in FAAL activity for the MtbFadD32 protein purified from M. smegmatis (FadD32_myco) compared with FadD32 from E. coli, with a decrease in the reaction rate of 30–50% (Fig. 4A). This percentage is in the same range as the one observed when using FadD32 co-expressed with PknB and purified from E. coli (Fig. 3A), thus indicating that FadD32 could also be phosphorylated in mycobacteria and that this phosphorylation attenuates FAAL activity. To validate this hypothesis, we used the STPK-specific protein phosphatase MspP to determine whether the decrease of FadD32_myco activity was specifically due to its phosphorylation status. FadD32_myco was incubated in the absence or presence of MspP in a phosphatase reaction prior to assaying the FAAL activity. Dephosphorylation of FadD32_myco was confirmed by Western blotting using anti-phosphothreonine antibodies (Fig. 4B), and activity of the dephosphorylated FadD32_myco was assayed. As shown for FadD32-P (Fig. 3C), dephosphorylation of FadD32_myco by MspP led to the relief of its inhibition and allowed recovery of most parts of the FAAL activity (Fig. 4C). These data demonstrate that the decrease of activity of the native FadD32_myco was specifically due to its phosphorylation status.

FIGURE 4.

Phosphorylation status and activity of FadD32 produced in mycobacteria. The FadD32 protein was produced either in E. coli (non-phosphorylated, FadD32) or in M. smegmatis (FadD32_myco). A, scatter plots showing maximum velocity Vmax for lauric acid (C12); values are representative of four sets of experiments with independent protein preparations ± S.D. The p value = 0.036 was calculated by Student's t test. B, SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis of FadD32 and FadD32_myco, treated or not with purified MspP in vitro. The proteins are detected by Stain-FreeTM SDS-PAGE technology (Bio-Rad) (upper panel), and their phosphorylation status was analyzed by immunoblot using anti-phosphothreonine antibodies (lower panel). C, FAAL activity of FadD32 and FadD32_myco, with or without MspP treatment, was assessed spectrophotometrically in the inorganic pyrophosphate-coupled assay. The Michaelis-Menten non-linear regression curves are displayed using C12 as substrate; values are means ± S.E. of four experimental replicates (upper panel). Lower panel, whisker plots showing activity (reaction velocity at 0.4 μm FadD32, 400 μm C12, and 2 mm ATP) of FadD32_myco with or without MspP treatment; the non-phosphorylated FadD32 proteins treated or not with MspP are shown as a control. Values represent eight experimental replicates issued from two sets of experiments with independent protein preparations; whiskers, minimum to maximum.

Moreover, analysis of steady-state kinetics of the FadD32-catalyzed reaction, using either FadD32_myco or its MspP-dephosphorylated form (FadD32_myco-DP), indicated that the apparent Km value for the fatty acid substrate (C12) was comparable, whereas maximal velocity (Vmax) was reduced for the phosphorylated form, and thus responsible for the altered overall activity (Table 1). Similar results (unaffected Km and lowered Vmax) were obtained for the cofactor ATP (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Steady-state kinetic parameters and thermal stability of wild-type and mutant FadD32 enzymes

The WT and mutant FadD32 proteins were purified from M. smegmatis, and the WT enzyme was treated with the mycobacterial phosphatase MspP to yield the dephosphorylated FadD32 (FadD32_myco-DP), used as a reference to calculate the percentage of activity using kcat values. Kinetic parameters and thermal stability of FadD32 purified from E. coli (FadD32) are also listed.

| Enzyme | Apparent kinetic parameters for lauric acid (C12) |

Thermal stability, | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Vmax | Km | kcat | Tm | |

| % | μm·min−1 | μm | min−1 | °C | |

| E. coli | |||||

| FadD32 | 109 | 0.66 ± 0.01 | 75.4 ± 4.5 | 1.64 ± 0.03 | 38.1 |

| M. smegmatis | |||||

| FadD32_myco-DP | 100 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 81.5 ± 4.1 | 1.51 ± 0.03 | 37.2 |

| FadD32_myco | 54 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 72.9 ± 4.7 | 0.81 ± 0.02 | 37.2 |

| FadD32_myco_T552V | 99 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 80.1 ± 4.4 | 1.50 ± 0.03 | 36.9 |

| FadD32_myco_T552D | 45 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 85.5 ± 6.4 | 0.68 ± 0.02 | 38.0 |

Thr-552 Phosphoacceptor Is Critical for FadD32 Activity

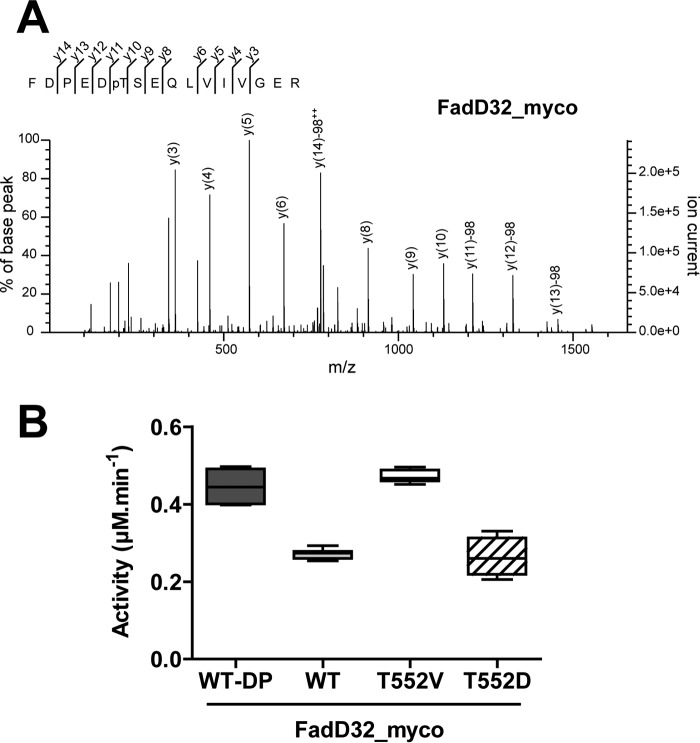

Having demonstrated that FadD32 was phosphorylated in vitro as well as in vivo, we inspected which phosphosite(s) was (were) involved in the PTM by mass spectrometry. Thus, FadD32 protein purified from mycobacteria was enzymatically digested with trypsin, and the generated peptides were analyzed by on-line liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Interestingly, the MS/MS analysis led to a high degree of sequence coverage for FadD32 (96%) and revealed the occurrence of a unique phosphorylated FadD32 tryptic peptide (Phe-547–Arg-562), unambiguously identifying Thr-552 as being phosphorylated (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Identification and role of Thr-552 phosphorylation in FadD32 activity. A, MS/MS spectrum of the mono-phosphorylated tryptic FadD32_myco peptide FDPEDpTSEQLVIVGER (547–562) (doubly charged precursor ion at m/z 957.4325). The y fragment ions of the peptide sequence are labeled in the spectrum. The y10 correspond to unphosphorylated serine. Starting from y11 (C-terminal fragment corresponding to Thr-552), all y fragments display loss of phosphoric acid (−98 (phosphate + H2O)), thus indicating unambiguously that the phosphate modification is located on Thr-552. pT = phosphorylated threonine residue; ++ = doubly charged ion; PE = internal fragment. B, FAAL activity of different FadD32 protein variants. Whisker plots showing activity (reaction velocity at 0.4 μm FadD32, 400 μm C12, and 2 mm ATP) of FadD32 produced in mycobacteria (FadD32_myco): WT, phospho-ablative (T552V) and phosphomimetic (T552D) mutants; the WT FadD32_myco dephosphorylated by MspP (WT-DP) is used as a control. Values represent eight experimental replicates, issued from two sets of experiments with independent protein preparations; whiskers, minimum to maximum.

To identify the functional consequences of phosphorylation on Thr-552, we generated and purified in M. smegmatis FadD32_myco phosphoablative and phosphomimetic mutants and measured their activities and kinetic parameters. First, we generated a FadD32_myco phosphoablative mutant in which the Thr-552 residue was substituted with a non-phosphorylable valine (FadD32_myco_T552V). Both FadD32_myco and FadD32_myco_T552V proteins, expressed and purified from mycobacteria, displayed very similar purification yields, thus indicating no apparent effect of the T552V mutation on protein expression. Thermal stability of FadD32 was examined in the mutant variant by differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF). The melting temperatures, Tm, were comparable between the phosphoablative mutant FadD32_myco_T552V, the wild-type FadD32_myco, and FadD32 from E. coli (Table 1), suggesting that the mutation did not affect the thermal stability of the proteins.

In addition, we investigated whether the decrease of the FAAL activity of phosphorylated FadD32 could be rescued in the phosphoablative mutant T552V. Accordingly, activity of the non-phosphorylable mutant FadD32_myco_T552V was measured and compared with that of the WT FadD32_myco, with the FadD32_myco dephosphorylated by MspP (FadD32_myco-DP) used as a non-phosphorylated control. As shown in Fig. 5B and Table 1, the activity loss in FadD32_myco was relieved in the non-phosphorylable FadD32_myco_T552V (activity raised up to 99% of control), thus confirming the critical role of Thr-552 in the phosphorylation-mediated negative regulation of FadD32.

To confirm the role of Thr-552 phosphorylation on FadD32 activity, we generated a T552D phosphomimetic mutant. In fact, earlier studies showed that the acidic Asp or Glu amino acids can mimic the effect of phosphorylation with regard to functional activity (23). We first expressed and purified the phosphomimetic FadD32_myco_T552D in M. smegmatis and checked its thermal stability. Again, the Tm value obtained for the T552D mutant was comparable with those for WT and the T552V variant (Table 1). Next, we determined the in vitro FAAL activity of this phosphomimetic and compared its enzymatic activity with those of dephosphorylated FadD32 (FadD32_myco-DP) or phosphorylated (FadD32_myco) in the presence of increasing concentrations of lauric acid (C12). Fig. 5B clearly shows a substantial activity reduction (by 55%) of the phosphomimetic mutant protein (Table 1).

The apparent kinetic parameters, kcat and Km, determined for WT and mutant FadD32 derivatives show similar Km values for the substrate C12 (Table 1), indicating that phosphomimetic and ablative Thr-552 mutations did not affect the affinity of the enzyme toward its substrate. However, the phosphomimetic mutant protein showed reduced catalytic turnover kcat compared with the dephosphorylated and phosphoablative T552V mutant (Fig. 5B and Table 1). The same parameters were also verified (unchanged Km and reduced kcat) for the cofactor ATP (data not shown). Altogether these results confirm the critical role of Thr-552 in FadD32 activity modulation by phosphorylation.

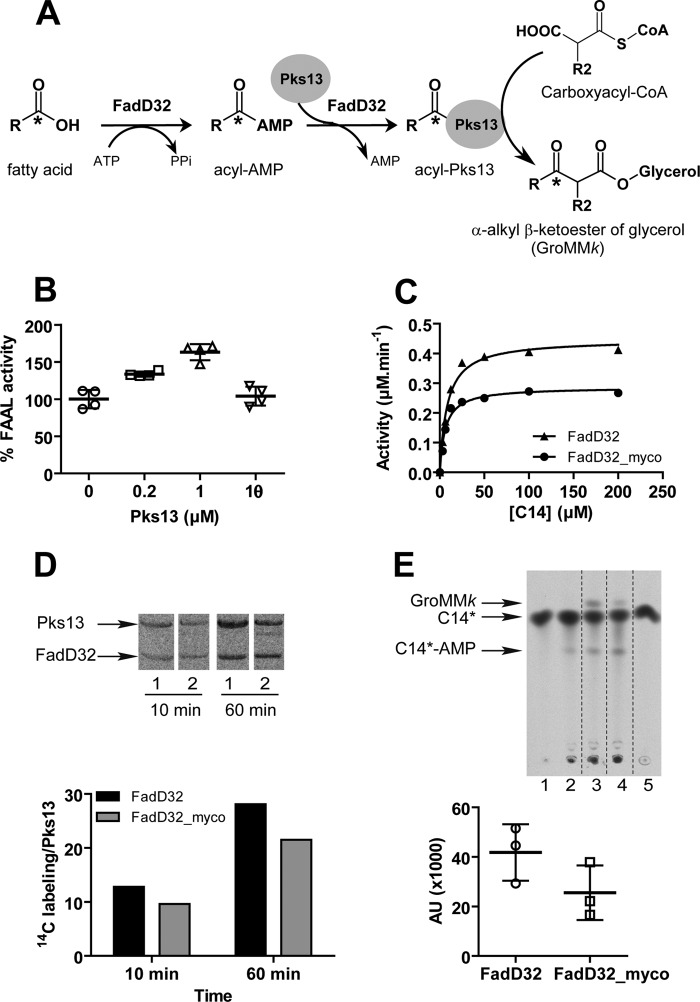

FadD32 Phosphorylation Impairs Mycolic Acid Condensation

FadD32 was shown to be essential in the mycolic condensation reaction. It represents the adenylation module of the condensing activity, which is responsible first for the formation of the acyl-adenylate and second for the transfer of the acyl chain onto the N-ACP domain of Pks13 (7–9). The latter condenses the FadD32-activated long-chain fatty acid with a carboxylated acyl-CoA (carboxyacyl-CoA) to yield the mycolic β-ketoester (α-alkyl β-ketoacyl derivative) (Fig. 6A). To investigate the impact of FadD32 phosphorylation on the entire condensation reaction, the condensing activity was assayed in the presence of either the phosphorylated isoform (FadD32_myco) or unphosphorylated FadD32 (FadD32).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of FadD32 phosphorylation on the FadD32/Pks13-catalyzed condensation reaction. A, scheme of in vitro FadD32-Pks13-coupled reaction releasing α-alkyl β-ketoester of glycerol (GroMMk). B, impact of Pks13 addition in the assay on FadD32 FAAL activity. Scatter plots showing reaction velocity of FadD32 (0.2 μm) in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of native Pks13 (0.2 or 1 μm) or heat-inactivated (θ) Pks13 (1 μm). Results are presented as the percentage of reaction velocity (mean value) of FadD32 without Pks13 as a control. C, FAAL activity of FadD32 phospho-isoforms (non-phosphorylated (FadD32) or produced in mycobacteria (FadD32_myco)) in the presence of Pks13. The Michaelis-Menten non-linear regression curves were assessed in a spectrophotometric assay carried out using myristic acid (C14) as substrate, and the reaction was started with addition of the mixture of Pks13 (0.4 μm) with 0.4 μm of either FadD32 (▴) or FadD32_myco (●). Mean and S.E. are shown for four experimental replicates. D, loading of labeled C14*-AMP produced by FadD32 isoforms onto Pks13. Reactions performed using the FadD32 substrate C14* were incubated 10 or 60 min, then loaded on SDS-PAGE, and revealed by autoradiography: FadD32 (lane 1); FadD32_myco (lane 2). Lower panel, quantification of radioactivity associated with Pks13. E, radio-TLC showing Pks13 condensing activity in the presence of FadD32 isoforms: FadD32 (lane 3) or FadD32_myco (lane 4). Lane 1: control without FadD32; lane 2: control without Pks13; lane 5: control C14* fatty acid. Lower panel, quantification (arbitrary units (AU)) of radiolabeled GroMMk formed using either FadD32 or FadD32_myco. Scatter plots display three experimental replicates ± S.D.; values are representative of two sets of experiments with independent protein preparations.

Prior to testing the impact of FadD32 phosphorylation on the condensation reaction, and given the absolute requirement of active FadD32 for the condensing activity of Pks13 (7, 8), we checked whether the presence of the latter enzyme would influence FadD32 FAAL activity. To test this, we measured the FAAL activity in the absence or presence of Pks13 (Fig. 6B). Indeed, native Pks13, but not heat-inactivated protein, enhances FadD32 activity in a dose-dependent manner, indicating a potentiation between FadD32 and Pks13 activities. Therefore, whether phosphorylation modifies FadD32 activity in the presence of the enhancing partner Pks13 was investigated by testing FadD32 and FadD32_myco activity in the presence of Pks13. As shown in Fig. 6C, FAAL activity of the phosphorylated FadD32 compared with non-phosphorylated FadD32 was equally impaired in the presence (36% reduction) (Fig. 6C) or absence of Pks13 (Fig. 4C).

Therefore, the impact of FadD32 phosphorylation on the condensation reaction was then determined. First, loading of the acyl-AMP formed ([1-14C]C14-AMP) onto Pks13 to yield acyl-Pks13 (Fig. 6A) was determined by following the radioactivity associated with Pks13 by SDS-PAGE in the presence of FadD32 isoforms (Fig. 6D). As shown for two loading reaction times (10 and 60 min), a decrease in FadD32 loading activity was observed in the presence of the phosphorylated FadD32_myco (Fig. 6D). Then, analysis by radio-TLC and phosphorimaging of the condensation products (α-alkyl β-ketoacyl of glycerol, GroMMk) catalyzed by Pks13 with both isoforms showed a decrease (by 40%) in product formation when FadD32 was phosphorylated (Fig. 6E). We thus may conclude that phosphorylation of FadD32 impairs both its acyl-AMP ligase activity and its transferase activity of the meromycolic chain onto Pks13, thus reducing the entire mycolic condensation activity.

Discussion

MA synthesis is established as a validated pathway for antituberculous drug discovery, and biochemical unraveling of many steps in this pathway has allowed the identification of numerous drug targets within the FAS-II elongation complex (e.g. KasA, KasB, MabA, HadAB/HadBC, and InhA) and in the mycolic condensation reaction (i.e. Pks13 and FadD32). Regulation of MA synthesis at the transcriptional level and/or by PTM (18) is one of the most interesting and challenging facets of M. tuberculosis biology, and it was found to impact MA biosynthetic enzyme activities, thus modulating cell envelope biogenesis (20, 21, 23).

Among the key enzymes involved in MA synthesis and essential for M. tuberculosis viability is FadD32, an adenylating enzyme catalyzing the activation of the very long-chain meromycolic acid prior to condensation with the α-chain to yield MA. FadD32 constitutes an attractive target for the development of new antituberculous drugs (6) and has indeed been identified as an important susceptible (15) and potentially druggable target (8, 30, 37). We have previously determined the biochemical and enzymatic properties of FadD32 (7, 8, 30), and we recently solved its three-dimensional structure in complex with alkyl adenylate inhibitors (35). The structure of Mtb FadD32 was also recently solved in complex with a sulfamoyl adenosine inhibitor (PhU-AMS) (38). In this study, we combined enzymatic characterization and mass spectrometry analysis to address the question of the putative regulation of this essential protein by PTM. We first showed that FadD32 produced in E. coli could be phosphorylated by mycobacterial STPKs both in vitro and by co-expression with the PknB kinase. Phosphorylation resulted in a significant loss (40%) of the FadD32 FAAL activity. Moreover, using the mycobacterial protein phosphatase, MspP, we demonstrated that STPK-mediated phosphorylation was the major factor involved in the FadD32 loss of activity. We also demonstrated that native MtbFadD32 expressed in the mycobacterial surrogate host M. smegmatis was phosphorylated and that this PTM specifically induces a decrease of its FAAL activity. This decrease of activity of phosphorylated FadD32 is consistent with the recognized effect of STPKs in modulating negatively the activity of other enzymes involved in MA synthesis (18).

FadD32, being the adenylation module of the condensing reaction, plays a critical role in MA synthesis by providing and then transferring the activated meromycolic chain onto Pks13, the enzyme that catalyzes the condensation of long-chain products of the two FAS systems to yield, upon reduction, mature MA (Fig. 1). As such, FadD32 phosphorylation variants potentially impact the condensing activity. Expectedly, we showed that phosphorylation of FadD32 likewise impairs the mycolic condensation activity of its partner Pks13 by virtue of decreased activity of the FadD32 enzyme. Earlier studies have shown that several members of the FAS-II pathway, namely KasA, KasB, MabA, HadAB, HadBC, InhA, as well as FabH that links the FAS-I and FAS-II pathways, are also regulated by phosphorylation attributed to STPKs (19, 22, 23, 25, 26). The identification of FadD32 as a novel substrate being phosphorylated by these kinases, along with other FAS enzymes, shed new light into the various combinations by which the mycolic acid synthesis may be regulated in vivo.

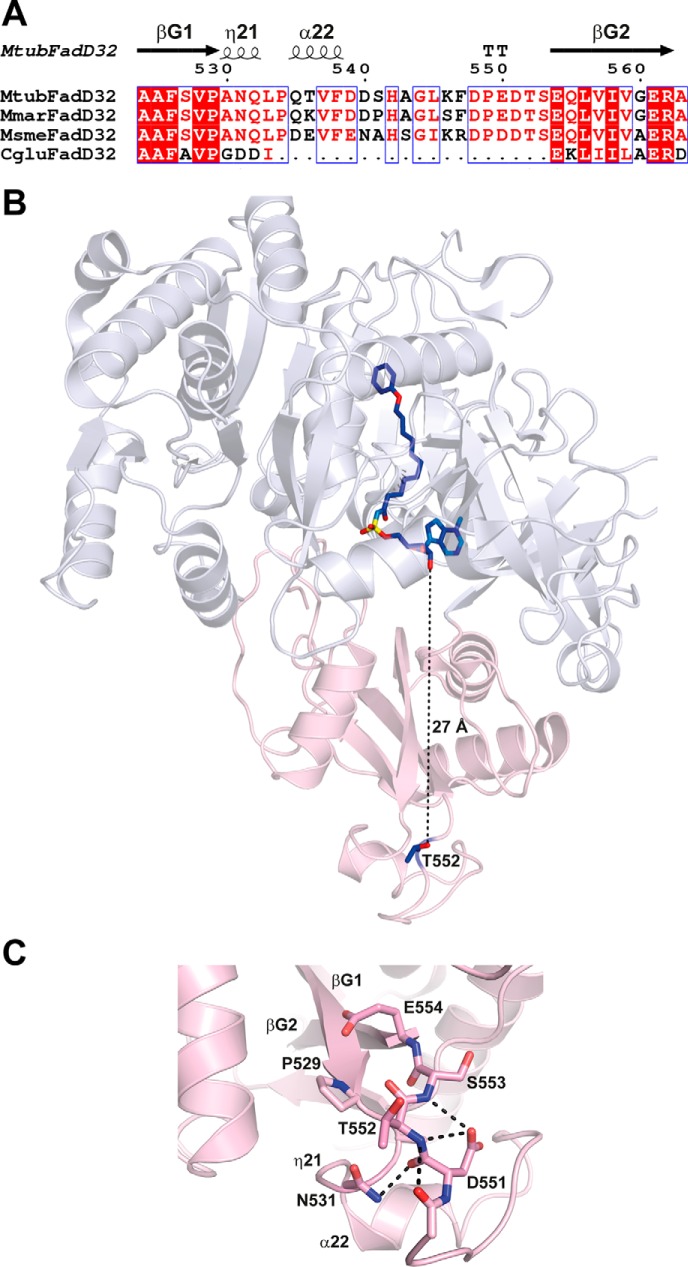

Mass spectrometry analyses established that FadD32 produced in mycobacteria was phosphorylated on Thr-552. Comparative enzymatic analysis of the native, the phosphoablative, and the phosphomimetic FadD32 derivatives showed that phosphorylation of this residue is critical in modulating FadD32 activity. Moreover, the importance of the Thr-552 phosphosite is consistent with phosphoproteomic studies also revealing its phosphorylated status in M. tuberculosis (24, 39). In line with the structures of FadD32 from Mycobacterium species, a pairwise alignment indicates that residue Thr-552 in M. tuberculosis is homologous to Thr-544 in Mycobacterium marinum and Thr-545 in M. smegmatis and belongs to the highly conserved insertion motif DP(E/D)DTSEQLVIV found among mycobacterial FadD32 (Fig. 7A) and compatible with the substrate recognition motif of the Pkn proteins (24). Also, this sequence motif contains an acidic glutamate residue and an isoleucine residue, at positions −2 and +6, respectively, and both have been shown to be a dominant motif responsible for specific phosphorylation by PknA, PknB, or PknD (24). The structure of MtbFadD32 recently published (38) confirms that Thr-552 is located on a solvent-exposed loop, fully accessible for phosphorylation and exactly at the opposite side of the hydrophobic tunnel dedicated to accommodate the acyl chain, as observed with the PhU-AMS inhibitor (Fig. 7, B and C). Interestingly, such position of the Thr residue located at 27 Å from the binding site could merely define an allosteric modulating site. How such a distant phosphorylation could modulate negatively the catalytic rate or change the conformational plasticity of the protein remains to be deciphered. One cannot rule out any phosphoprotein-protein interaction mediation through phospho-dependent binding of protein during the cell wall lipid cycle. We cannot exclude conformational rearrangement upon PTM, as Thr-552 belongs to a 150-residue modular domain of FadD32 at the flexible C terminus (residues 493–637). One attractive hypothesis could be a regulatory role for this C-terminal domain, which is further located at the entrance of the substrate.

FIGURE 7.

Thr-552 is located in an extended loop fully accessible for phosphorylation by STPKs. A, structure-based sequence alignment of FadD32 from M. tuberculosis, M. marinum, M. smegmatis and Corynebacterium glutamicum in the loop region carrying Thr-552. Sequence homology is highlighted in red, and sequence identity is shown as white letters on a red background. Secondary structure elements (arrows for β-strands and coils for α- and η-helices) are indicated at the top and numbered as in Ref. 35. B, structure of MtbFadD32 (Protein Data Bank code 5HM3). The N- and C-terminal domains are colored blue white and light pink, respectively. The side chain of Thr-552 and the bound PhU-AMS molecule, as found in the structure of MtbFadD32, are shown as a stick representation. C, zoom region of the loop insertion in MtbFadD32 carrying Thr-552. The side chains of residues found within 6 Å of Thr-552 are displayed. Contacts between polar atoms within a distance of 3.5 Å are displayed as dotted lines.

One can also envision that local structural rearrangements, even minor, occurring upon Thr-552 phosphorylation may induce or favor other PTM, such as lysine acetylation, a phenomenon also reported to negatively regulate M. tuberculosis mycobactin FadD33 enzyme activity (40). In fact, it was proposed (41) that both PTMs (phosphorylation and acetylation) might coexist in M. tuberculosis proteins at the same time to jointly regulate key metabolic processes. In the latter proteome-wide lysine acetylation study (41), the authors identified a Lys acetylation site (Lys-568) in FadD32, which is, according to the 3D structure, distant (at 40 Å) from the phosphosite.

While in M. tuberculosis, 11 STPKs are present in the genome, PstP (the orthologue of the M. smegmatis MspP) is the only Ser/Thr phosphatase (32). The pstP gene exists in an operon together with the genes encoding PknA and PknB STPKs, whose dephosphorylation by PstP causes their inactivation. With PstP being the unique Ser/Thr phosphatase, it is presumed to dephosphorylate all of the STPKs and their substrates. This has been reported for a few M. tuberculosis proteins. For instance, EmbR, a transcription factor of the embCAB operon, is a substrate of multiple STPKs and is dephosphorylated by PstP, which regulates its DNA-binding ability (42). Here, we demonstrate for the first time that FadD32 acyl-AMP ligase activity can be reversibly regulated by STPK post-translational phosphorylation and MspP dephosphorylation. This finding highlights the critical role of the dual regulation by protein phosphatase and STPKs within the mycobacterial cell. In conclusion, an array of multiple kinases, acting at various substrates, with multiple levels of fine-tuning of enzymatic activity brings to light an elaborate manner in which mycolic acid metabolism can be tightly regulated for the production of the essential cell envelope components that could be targeted for future anti-tuberculosis strategies.

Experimental Procedures

Plasmids

For expression and purification of FadD32 in mycobacteria, the pLD1-fadD32 vector was constructed by modifying the pMtu-NDH2 (an IPTG-inducible vector containing NDH2 with the C-terminal His tag developed in AstraZeneca (43, 44). The RBS-NDH2-His region of pMtu-NDH2 was then removed following digestion with FastDigest (FD) BamHI-FD NdeI (ThermoFisher). A synthetic DNA sequence with a 3′-A overhang at each end for TA cloning was prepared by using two complementary primers (Sigma) (pLD1 modification sequence: with a consensus Shine-Dalgarno sequence upstream of a His tag, a 5′ BamHI restriction site and 3′ NotI and NdeI restriction sites). After TA cloning in pGEM®-T Easy Vector (Promega) and FD NdeI-FD BamHI digestion, the pLD1 modification sequence was inserted into the pMtu-NDH2 digested with the same restriction enzymes, to obtain pLD1 vector. Then, the fadD32 ORF from strain H37Rv was PCR-amplified using the primers fadD32F (GCCATCGATATGTTTGTGACAGGAGAGAGTGGGATGGCGTACC) and fadD32R (AGCATCGATACCGTTAGCTCGGCCCTTT). The forward primer contained a 5′ end BamHI restriction site, and the reverse primer contained a 5′ end NdeI restriction site. The PCR product was digested with FD BamHI and FD NdeI and cloned into pLD1 to obtain pLD1-fadD32. All steps were checked by DNA sequencing (Eurofins Genomics, Germany).

To obtain expression plasmids in mycobacteria for mutant FadD32 derivatives, the phosphoablative T552V and phosphomimetic T552D mutations were introduced into the pLD1-fadD32 plasmid. The plasmids were subjected to site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) and the following primer pairs: fadD32_myco_T552V_F, 5′-CAGCTGCTCGGAGACGTCCTCGGGGTCGAAT-3′, and fadD32_myco_T552V_R, 5′-CGACCCCGAGGACGTCTCCGAGCAGCTG-3′; fadD32_myco_T552D-F, 5′-CAGCTGCTCGGAGTCGTCCTCGGGGTCGAA-3′, and fadD32_myco_T552D_R, 5′-CGACCCCGAGGACGACTCCGAGCAGCTG-3′. The mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Eurofins Genomics, Germany).

Protein Production and Purification in E. coli

The production and purification of the His tag FadD32 protein from M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Rv3801c) using the pET15b-fadD32 plasmid was performed as described previously (35). For co-expression of FadD32 and M. tuberculosis PknB in E. coli, BL21 StarTM (DE3) One Shot® cells were transformed with both the pET15b-fadD32 plasmid and the pCDFDuet-1 vector carrying in its MCS2 the sequence encoding the untagged PknB kinase domain. Transformants were selected on LB agar plates supplemented with 50 μg/ml carbenicillin and 100 μg/ml spectinomycin. The co-expression of FadD32 and PknB proteins was then performed using auto-inducible medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml carbenicillin and 100 μg/ml spectinomycin, and further purification of His tag FadD32 was performed as described (18). The purified FadD32 protein samples were checked by SDS-PAGE and Instant Blue staining, concentrated, and stored at −20 °C in 50% glycerol (v/v).

Protein Production and Purification in M. smegmatis mc2155

The plasmids pLD1-fadD32, pLD1-fadD32_myco_T552V, and pLD1-fadD32_myco_T552D were electroporated into M. smegmatis mc2155 GroEL1ΔC (32). Transformants were selected on 7H10 agar plates with ADC enrichment and hygromycin B (150 μg/ml). Starter cultures were grown for 48 h and then were diluted in 7H9 medium (Difco) supplemented with glycerol (30 g/liter), Tween 80 (0.05%), and hygromycin B (150 μg/ml). The resulting cultures were incubated with shaking (180 rpm) at 37 °C, and the protein overexpression was induced with IPTG at 0.5 mm final (Euromedex, France). Cells were harvested 24 h after IPTG induction, washed with 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), and pelleted by centrifugation at 4000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. Cell pellets were then resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol (v/v), 30 mm imidazole, 500 mm NaCl, and 2 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride (Euromedex). The suspension was disrupted with a cell disruptor (One Shot Model, Constant System Ltd., France) and centrifuged for 45 min at 40,000 × g at 4 °C to obtain the clarified lysate. Subsequent purification steps were performed as described elsewhere (18).

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

The protein sample, after reduction and alkylation of cysteines, was separated by 12% acrylamide SDS-PAGE. Proteins were visualized by Instant Blue (Expedeon) staining, and in-gel tryptic digestion was performed on the specific slice. The dried tryptic peptides were dissolved in 2% acetonitrile, 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid for further MS analysis. Peptides were analyzed by nanoLC-MS/MS using an Ultimate 3000 NRS system (Dionex) coupled to an QExactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Five μl of sample, after desalting, were separated on analytical C-18 column (in-house made C18 microcolumn, 75 μm inner diameter × 50 cm) equilibrated in 95% solvent A (5% acetonitrile, 0.2% formic acid) and 5% solvent B (80% acetonitrile, 0.2% formic acid). The peptides were eluted using a 5–50% gradient of solvent B during 105 min at a 300 nl/min flow rate. The QExactive Plus mass spectrometer was operated in data-dependent acquisition mode with the XCalibur software. The 10 most intense ions per survey scan were selected for higher energy collisional dissociation fragmentation, and the resulting fragment ions were analyzed in the Orbitrap. The Mascot Daemon software version 2.5.0 (Matrix Science) was used to perform database searches. The data were searched against the SwissProt 20150320 (547,964 sequences; 195,174,196 residues), taxonomy: M. tuberculosis complex (6,361 sequences) protein database. False discovery rates less than 1% for peptide identifications and false discovery rates less than 1% for protein identifications were applied for data validation using the in-house developed Proline software.

In Vitro Kinase Assays

In vitro phosphorylation was performed with 4 μg of wild-type FadD32 in 20 μl of buffer P (25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 1 mm DTT, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 50 μm ATP), 200 μCi ml−1 (65 nm) [γ-33P]ATP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, 3000 Ci mmol−1), and 0.5 μg of kinase to obtain the optimal autophosphorylation activity for each mycobacterial kinase for 30 min at 37 °C. Each reaction mixture was stopped by addition of an equal volume of 5× Laemmli buffer, and the mixture was heated at 100 °C for 5 min. After electrophoresis, gels were soaked in 16% TCA for 10 min at 90 °C, and dried. Radioactive proteins were visualized by autoradiography using direct exposure to films.

In Vitro Dephosphorylation Assays

In vitro dephosphorylation assays were performed using 10 μg (24 μm final) of FadD32 protein derivatives in phosphatase buffer (25 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm MnCl2) with 5 μg of M. smegmatis phosphatase MspP (31) for 90 min at 30 °C. To analyze the dephosphorylation of FadD32 by electrophoresis and immunoblotting, the reaction mixture was stopped by addition of an appropriate volume of 4× NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen), and heated at 70 °C for 10 min before loading on gel. To further measure enzymatic activity of dephosphorylated FadD32, the dephosphorylation reaction mixture was diluted 60× to obtain 400 nm FadD32 in the spectrophotometric assay, thus diluting the MnCl2 in the FAAL reaction down to 83 μm, which allowed FadD32 to exhibit 80% of its full FAAL activity (IC50 of MnCl2 = 233 μm).

Phostag SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

The Phostag reagent, when present, and its associated divalent cation Zn2+ form a complex with the phosphorylated FadD32 isoforms, thus retarding protein migration and thereby revealing phosphorylation status, further detected by Western blotting. The Zn2+/PhostagTM using a pH-neutral gel system was prepared as described (45). Briefly, the stacking Zn2+/PhostagTM gel buffer contained 4% acrylamide/bisacrylamide (37.5:1), 357 mm BisTris (pH 6.8), 0.1% v/v TEMED, 0.05% w/v ammonium persulfate. The separating Zn2+/PhostagTM gel contained 8% acrylamide/bisacrylamide (37.5:1), 357 mm BisTris (pH 6.8), 50 μm PhostagTM (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Japan), 100 μm Zn(NO3)2, 0.05% v/v TEMED, and 0.025% w/v ammonium persulfate. Following transfer to 0.2-μm PVDF membrane, His tag FadD32 was detected using mouse monoclonal anti-poly-His antibodies (Sigma) diluted 1:5000; HRP-conjugated goat antibodies against mouse (Bio-Rad) were diluted 1:10,000 and used as secondary antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were revealed with Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare).

For anti-phosphothreonine immunoblotting, 3 μg of purified FadD32 derivatives were loaded on Mini-PROTEAN® TGX Stain-FreeTM 4–20% precast gels (Bio-Rad), and the gel was transferred to 0.2-μm PVDF membrane. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against phosphothreonine (Invitrogen) were diluted 1:250 (1 μg/ml), and HRP-conjugated goat antibodies against rabbit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) used as secondary antibodies were diluted 1:5000. Immunoreactive bands were revealed with Chemidoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

Kinetic Experiments

The FadD32 FAAL enzyme activity was measured using the PiColorLockTM gold kit (Innova Biosciences, Cambridge, UK) as described previously (35). Briefly, assays were performed in quadruplicate in 384-well polystyrene microplates (Greiner Bio One, Courtaboeuf, France) in 30 μl of reaction mix containing 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 8 mm MgCl2, 0.001% Brij®35, 2 mm ATP, 1 mm 1,4-dithiothreitol, 2 milliunits/ml pyrophosphatase (Sigma), and varying concentration of lauric acid (C12). Reactions were started by adding 400 nm FadD32 in the assay and incubated 40 min at room temperature. For FAAL activity of FadD32 in the presence of Pks13, the reaction mixture contained 200 nm FadD32, and either 200 nm, 1 μm Pks13, or 1 μm heat-inactivated Pks13. A reaction without substrate was performed in each experiment and used as blank (for Km and Vmax determinations).

For apparent kinetic parameter determinations (Km, Vmax, and kcat), the initial velocities were measured (incubation time of 40 min) as a function of the studied substrate concentration at saturating concentrations of the non-varied substrate. The saturation curve was fit by non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 5.04 Equation 1,

where Vmax is the maximal velocity; [S] is the substrate concentration, and Km is the Michaelis-Menten constant. Kinetic parameters for fatty acids were determined at fixed concentrations of ATP (2 mm) and by varying the concentrations of the fatty acid (0–400 μm for C12 or 0 to 200 μm C14).

Thermostability of FadD32

DSF was used to characterize the thermal stability of the mutants. 20-μl mixtures of enzyme (4 μm), SYPRO-orange (5×) (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK), 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), and 500 mm NaCl were exposed to a temperature gradient from 15 to 80 °C with a 0.3 °C increment. All measurements were performed in triplicate in 96-well plates (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). The thermal transition was monitored using a RTQPCR CFX96 real time system (Bio-Rad). Tm was given by the inflection point of the curve relative fluorescence units = f(T). Samples used for DSF experiments were stored at −80 °C without glycerol.

Loading of [1-14C]acyl-AMP onto Pks13 Protein and Condensation Assays

The phosphopantetheinylated Pks13 protein was produced in E. coli by co-expressing the M. tuberculosis H37Rv pks13 (Rv3800c) gene with the sfp gene encoding the phosphopantetheinyl transferase from Bacillus subtilis and purified as described previously (7). The loading of [1-14C]C14-AMP onto Pks13 protein and condensation assays were performed as described previously with minor modifications (7, 9). Condensation assays contained 40 μm [1-14C]myristic acid (C14*; specific activity, 54 mCi/mmol; Bioisotop Hartmann Analytic) and 40 μm carboxy-C16-CoA (synthesized and purified as described previously (7)), 8 mm MgCl2, 2 mm ATP, 0.001% Brij 35 in 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.2). The reactions (total volume, 10 μl) were started by the addition of 2 μm FadD32 or FadD32_myco and 2 μm Pks13 conserved at −20 °C in 50% glycerol, incubated for 1 h at 30 °C, and then stopped at −20 °C. Control experiments without the indicated reagent(s) or without FadD32 or Pks13 were performed, as mentioned in the figure legends. Intact media of condensation assays were analyzed by TLC on Silica Gel G60 plates developed with CHCl3/CH3OH, 9:1. The loading of C14*-AMP onto Pks13 (10 μl) experiments was performed in the same medium used for condensation assays, but without carboxy-C16-CoA, and incubated for 1 h at 30 °C. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide). The radioactive condensation product, α-alkyl β-ketoester of glycerol (GroMMk), and the labeled ligand loaded onto Pks13 protein were quantified by phosphorimaging and ImageQuant software (Variable Mode Imager Typhoon TRIO, Amersham Biosciences). The radioactivity associated with the Pks13 band was normalized to its density, as quantified by ImageLab software (Bio-Rad) after Instant Blue staining.

Author Contributions

N. L., V. M., and H. M. conceived and designed the experiments. N. L., V. M., N. E., M. M., F. B., S. G., V. G., G. A-L., M. B., and H. M. performed and analyzed the experiments. A. S. and O. B-S. performed and analyzed the mass spectrometry data of protein modifications. V. G., G. A-L., P. A., and L. M. analyzed protein sequences and structures. N. L., V. M., M. D., and H. M. wrote the manuscript, with contributions from all the authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Elke Noens for providing the M. smegmatis GroEL1ΔC strain and to Dr. Parvinder Kaur and Prof. Santanu Datta for the pMtu-ndh2 vector. The differential scanning fluorimetry equipment used in this study is part of the Integrated Screening Platform of Toulouse (PICT, IBiSA).

This work was supported in part by European Union NM4TB, Grant LSHP-CT-2005-018923, and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche, FASMY, Grant ANR-14-CE16-0012. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- MA

- mycolic acid

- FAAL

- fatty acyl-AMP ligase

- PKS

- polyketide synthase

- PTM

- post-translational modification

- STPK

- serine/threonine protein kinase

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- FAS

- fatty acid synthase

- IPTG

- isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside

- FD

- FastDigest

- DSF

- differential scanning fluorimetry

- TEMED

- N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine

- ACP

- acyl carrier protein.

References

- 1. Marrakchi H., Lanéelle M. A., and Daffé M. (2014) Mycolic acids: structures, biosynthesis, and beyond. Chem. Biol. 21, 67–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zuber B., Chami M., Houssin C., Dubochet J., Griffiths G., and Daffé M. (2008) Direct visualization of the outer membrane of mycobacteria and corynebacteria in their native state. J. Bacteriol. 190, 5672–5680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sani M., Houben E. N., Geurtsen J., Pierson J., de Punder K., van Zon M., Wever B., Piersma S. R., Jiménez C. R., Daffé M., Appelmelk B. J., Bitter W., van der Wel N., and Peters P. J. (2010) Direct visualization by cryo-EM of the mycobacterial capsular layer: a labile structure containing ESX-1-secreted proteins. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gokhale R. S., Sankaranarayanan R., and Mohanty D. (2007) Versatility of polyketide synthases in generating metabolic diversity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17, 736–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Trivedi O. A., Arora P., Sridharan V., Tickoo R., Mohanty D., and Gokhale R. S. (2004) Enzymic activation and transfer of fatty acids as acyl-adenylates in mycobacteria. Nature 428, 441–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Duckworth B. P., Nelson K. M., and Aldrich C. C. (2012) Adenylating enzymes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis as drug targets. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 12, 766–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gavalda S., Léger M., van der Rest B., Stella A., Bardou F., Montrozier H., Chalut C., Burlet-Schiltz O., Marrakchi H., Daffé M., and Quémard A. (2009) The Pks13/FadD32 crosstalk for the biosynthesis of mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19255–19264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Léger M., Gavalda S., Guillet V., van der Rest B., Slama N., Montrozier H., Mourey L., Quémard A., Daffé M., and Marrakchi H. (2009) The dual function of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis FadD32 required for mycolic acid biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 16, 510–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gavalda S., Bardou F., Laval F., Bon C., Malaga W., Chalut C., Guilhot C., Mourey L., Daffé M., and Quémard A. (2014) The polyketide synthase Pks13 catalyzes a novel mechanism of lipid transfer in mycobacteria. Chem. Biol. 21, 1660–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Portevin D., De Sousa-D'Auria C., Houssin C., Grimaldi C., Chami M., Daffé M., and Guilhot C. (2004) A polyketide synthase catalyzes the last condensation step of mycolic acid biosynthesis in Mycobacteria and related organisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 314–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Portevin D., de Sousa-D'Auria C., Montrozier H., Houssin C., Stella A., Lanéelle M. A., Bardou F., Guilhot C., and Daffé M. (2005) The acyl-AMP ligase FadD32 and AccD4-containing acyl-CoA carboxylase are required for the synthesis of mycolic acids and essential for mycobacterial growth: identification of the carboxylation product and determination of the acyl-CoA carboxylase components. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8862–8874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Forti F., Crosta A., and Ghisotti D. (2009) Pristinamycin-inducible gene regulation in mycobacteria. J. Biotechnol. 140, 270–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boldrin F., Casonato S., Dainese E., Sala C., Dhar N., Palù G., Riccardi G., Cole S. T., and Manganelli R. (2010) Development of a repressible mycobacterial promoter system based on two transcriptional repressors. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cortes M., Singh A. K., Reyrat J. M., Gaillard J. L., Nassif X., and Herrmann J. L. (2011) Conditional gene expression in Mycobacterium abscessus. PLoS One 6, e29306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carroll P., Faray-Kele M. C., and Parish T. (2011) Identifying vulnerable pathways in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by using a knockdown approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 5040–5043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wehenkel A., Bellinzoni M., Graña M., Duran R., Villarino A., Fernandez P., Andre-Leroux G., England P., Takiff H., Cerveñansky C., Cole S. T., and Alzari P. M. (2008) Mycobacterial Ser/Thr protein kinases and phosphatases: physiological roles and therapeutic potential. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784, 193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Av-Gay Y., and Everett M. (2000) The eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr protein kinases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol 8, 238–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Molle V., and Kremer L. (2010) Division and cell envelope regulation by Ser/Thr phosphorylation: Mycobacterium shows the way. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 1064–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Slama N., Leiba J., Eynard N., Daffé M., Kremer L., Quémard A., and Molle V. (2011) Negative regulation by Ser/Thr phosphorylation of HadAB and HadBC dehydratases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis type II fatty-acid synthase system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 412, 401–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Corrales R. M., Molle V., Leiba J., Mourey L., de Chastellier C., and Kremer L. (2012) Phosphorylation of mycobacterial PcaA inhibits mycolic acid cyclopropanation: consequences for intracellular survival and for phagosome maturation block. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 26187–26199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vilchèze C., Molle V., Carrère-Kremer S., Leiba J., Mourey L., Shenai S., Baronian G., Tufariello J., Hartman T., Veyron-Churlet R., Trivelli X., Tiwari S., Weinrick B., Alland D., Guérardel Y., Jacobs W. R. Jr, and Kremer L. (2014) Phosphorylation of KasB regulates virulence and acid-fastness in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Veyron-Churlet R., Zanella-Cléon I., Cohen-Gonsaud M., Molle V., and Kremer L. (2010) Phosphorylation of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein reductase MabA regulates mycolic acid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12714–12725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Molle V., Gulten G., Vilchèze C., Veyron-Churlet R., Zanella-Cléon I., Sacchettini J. C., Jacobs W. R. Jr., and Kremer L. (2010) Phosphorylation of InhA inhibits mycolic acid biosynthesis and growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 78, 1591–1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Prisic S., Dankwa S., Schwartz D., Chou M. F., Locasale J. W., Kang C. M., Bemis G., Church G. M., Steen H., and Husson R. N. (2010) Extensive phosphorylation with overlapping specificity by Mycobacterium tuberculosis serine/threonine protein kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 7521–7526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Molle V., Brown A. K., Besra G. S., Cozzone A. J., and Kremer L. (2006) The condensing activities of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis type II fatty-acid synthase are differentially regulated by phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30094–30103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Veyron-Churlet R., Molle V., Taylor R. C., Brown A. K., Besra G. S., Zanella-Cléon I., Fütterer K., and Kremer L. (2009) The Mycobacterium tuberculosis β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III activity is inhibited by phosphorylation on a single threonine residue. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6414–6424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Khan S., Nagarajan S. N., Parikh A., Samantaray S., Singh A., Kumar D., Roy R. P., Bhatt A., and Nandicoori V. K. (2010) Phosphorylation of enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase InhA impacts mycobacterial growth and survival. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 37860–37871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baronian G., Ginda K., Berry L., Cohen-Gonsaud M., Zakrzewska-Czerwińska J., Jakimowicz D., and Molle V. (2015) Phosphorylation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis ParB participates in regulating the ParABS chromosome segregation system. PLoS One 10, e0119907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Molle V., Leiba J., Zanella-Cléon I., Becchi M., and Kremer L. (2010) An improved method to unravel phosphoacceptors in Ser/Thr protein kinase-phosphorylated substrates. Proteomics 10, 3910–3915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Galandrin S., Guillet V., Rane R. S., Léger M., N R., Eynard N., Das K., Balganesh T. S., Mourey L., Daffé M., and Marrakchi H. (2013) Assay development for identifying inhibitors of the mycobacterial FadD32 activity. J. Biomol. Screen. 18, 576–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bellinzoni M., Wehenkel A., Shepard W., and Alzari P. M. (2007) Insights into the catalytic mechanism of PPM Ser/Thr phosphatases from the atomic resolution structures of a mycobacterial enzyme. Structure 15, 863–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sajid A., Arora G., Singhal A., Kalia V. C., and Singh Y. (2015) Protein phosphatases of pathogenic bacteria: role in physiology and virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 69, 527–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sajid A., Arora G., Gupta M., Upadhyay S., Nandicoori V. K., and Singh Y. (2011) Phosphorylation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ser/Thr phosphatase by PknA and PknB. PLoS One 6, e17871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kinoshita-Kikuta E., Kinoshita E., and Koike T. (2015) Neutral phosphate-affinity SDS-PAGE system for profiling of protein phosphorylation. Methods Mol. Biol. 1295, 323–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guillet V., Galandrin S., Maveyraud L., Ladevèze S., Mariaule V., Bon C., Eynard N., Daffé M., Marrakchi H., and Mourey L. (2016) Insight into structure-function relationships and inhibition of the fatty Acyl-AMP ligase (FadD32) orthologs from mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 7973–7989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Noens E. E., Williams C., Anandhakrishnan M., Poulsen C., Ehebauer M. T., and Wilmanns M. (2011) Improved mycobacterial protein production using a Mycobacterium smegmatis groEL1ΔC expression strain. BMC Biotechnol. 11, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stanley S. A., Kawate T., Iwase N., Shimizu M., Clatworthy A. E., Kazyanskaya E., Sacchettini J. C., Ioerger T. R., Siddiqi N. A., Minami S., Aquadro J. A., Grant S. S., Rubin E. J., and Hung D. T. (2013) Diarylcoumarins inhibit mycolic acid biosynthesis and kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis by targeting FadD32. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 11565–11570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kuhn M. L., Alexander E., Minasov G., Page H. J., Warwrzak Z., Shuvalova L., Flores K. J., Wilson D. J., Shi C., Aldrich C. C., and Anderson W. F. (2016) Structure of the essential Mtb FadD32 enzyme: a promising drug target for treating tuberculosis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2, 579–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fortuin S., Tomazella G. G., Nagaraj N., Sampson S. L., Gey van Pittius N. C., Soares N. C., Wiker H. G., de Souza G. A., and Warren R. M. (2015) Phosphoproteomics analysis of a clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing isolate: expanding the mycobacterial phosphoproteome catalog. Front. Microbiol. 6, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vergnolle O., Xu H., and Blanchard J. S. (2013) Mechanism and regulation of mycobactin fatty acyl-AMP ligase FadD33. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 28116–28125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xie L., Wang X., Zeng J., Zhou M., Duan X., Li Q., Zhang Z., Luo H., Pang L., Li W., Liao G., Yu X., Li Y., Huang H., and Xie J. (2015) Proteome-wide lysine acetylation profiling of the human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 59, 193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sharma K., Gupta M., Krupa A., Srinivasan N., and Singh Y. (2006) EmbR, a regulatory protein with ATPase activity, is a substrate of multiple serine/threonine kinases and phosphatase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEBS J. 273, 2711–2721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shirude P. S., Paul B., Roy Choudhury N., Kedari C., Bandodkar B., and Ugarkar B. G. (2012) Quinolinyl pyrimidines: potent inhibitors of NDH-2 as a novel class of anti-TB agents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 3, 736–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaur P., Agarwal S., and Datta S. (2009) Delineating bacteriostatic and bactericidal targets in mycobacteria using IPTG inducible antisense expression. PLoS One 4, e5923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bekešová S., Komis G., Křenek P., Vyplelová P., Ovečka M., Luptovčiak I., Illés P., Kuchařová A., and Šamaj J. (2015) Monitoring protein phosphorylation by acrylamide pendant Phos-Tag in various plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]