Abstract

Background

Data surrounding risk factors for readmissions following surgical resection for lung cancer are limited and largely focus on postoperative outcomes including complications and hospital length of stay. The current study aims to identify preoperative risk factors for postoperative readmission in early stage lung cancer patients.

Methods

The National Cancer Data Base was queried for all early stage lung cancer patients with clinical stage ≤T2N0M0 who underwent lobectomy in 2010–2011. Patients with unplanned readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge were identified. Univariate analysis was utilized to identify pre-operative differences between readmitted and non-readmitted cohorts; multivariable logistic regression was used to identify risk factors resulting in readmission.

Results

A total of 840/19,711 (4.3%) patients were readmitted postoperatively. Male patients were more likely to be readmitted vs. females (4.9 vs. 3.8%, p<0.001), as were those who received surgery at a non-academic vs. an academic facility (4.6 vs. 3.6%; p=0.001) and had underlying medical comorbidities (Charlson/Deyo Score 1+ vs. 0; 4.8 vs. 3.7%; p<0.001). Readmitted patients had a longer median hospital LOS; (6 vs. 5 days; p<0.001) and were more likely to have a minimally invasive approach (5.1% VATS vs. 3.9% open; p<0.001). In addition to these aforementioned variables, multivariable logistic regression analysis identified that median household income level, insurance status (government vs. private), and geographic residence (metro vs. urban vs. rural) had significant influence on readmission.

Conclusions

Socioeconomic factors identified significantly influence hospital readmission and should be considered during preoperative and postoperative discharge planning for patients with early stage lung cancer.

Keywords: Lung cancer surgery, Lobectomy, Readmissions

Postoperative readmissions have become both an indicator of healthcare quality and a financial variable impacting hospital reimbursement. When the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) started penalizing hospitals for “excessive” readmissions in 2012, both hospital administrators and doctors alike started focusing on ways in which unnecessary hospital readmissions might be preventable.1,2 As a result, recent studies have identified risk factors for readmission following surgery. Common postulated risks for unplanned postoperative readmission include postoperative complications,3–5 hospital length of stay (LOS),6–8 patient race,9–11 and site of hospital care.12

The current data surrounding risk factors for readmissions following surgical resection for lung cancer are limited, with relatively non-generalizable results. In 2013, Freeman et al. reported that readmission rates following lobectomy via open thoracotomy for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are inversely associated with postoperative LOS; minimally invasive approaches were excluded from their analysis.6 In 2014, Hu et al. concluded that preoperative comorbidities, procedure type and socioeconomic factors all increased the risk of postoperative readmission following surgical resection of lung cancer. The study utilized Medicare data and was thus limited to patients ≥66 years old.13

Taking these data into account, identification of patients at high-risk for readmission is an essential part of the pre-operative evaluation. If providers are able to recognize patients more likely to be readmitted, it will enable them to appropriately focus limited resources available to them. Furthermore, such data allow for appropriate risk stratification, which ultimately impacts the way in which surgical outcomes data are interpreted and may influence reimbursement rates. The current study utilizes a large, national, generalizable dataset and aims to identify preoperative risk factors for postoperative readmission in early stage lung cancer patients. We hypothesize that socioeconomic factors are part of equation that links to risk for hospital readmission following lobectomy.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Data Collection and Definition of Study Variables

The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) Participant Use File 2011, an oncology outcomes database administered by the American Cancer Society and the American College of Surgeons, was queried for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with clinical stage ≤T2N0M0 who underwent lobectomy in 2010–2011. All lung cancers were staged using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th Edition of Lung Cancer Staging guidelines

The primary outcome variable of interest was unplanned readmission to the same facility within 30 days of discharge following surgical resection for early-stage NSCLC. Patient demographics (gender, age, race), socioeconomic variables, preexisting comorbidities, and facility type were examined in relation to readmission status. The facility type was determined by Commission on Cancer program accreditation level and was based on types of services provided and case volume.14 Definitions of socioeconomic variables are shown in Table 1.15

Table 1.

Definition of Socioeconomic Variables

| Income |

|

| Education |

|

| Geographic Setting17 |

|

Because surgical approach (video assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) vs. open thoracotomy is decided upon prior to arrival in the operating room, it was considered a pre-operative variable and was defined on an intention-to-treat basis (thoracoscopic cases converted to open were classified as VATS).

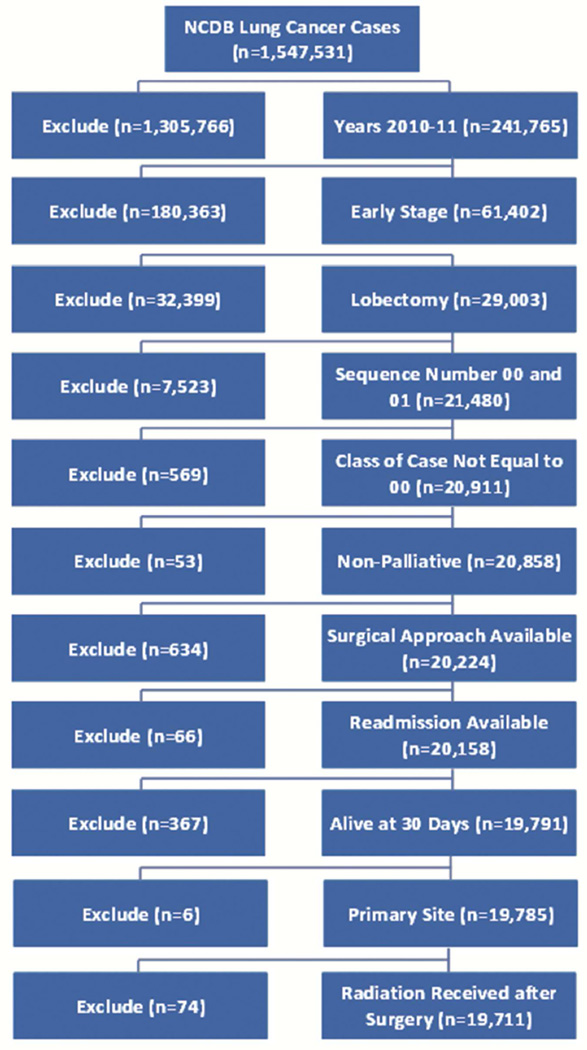

Cases with unknown surgical approach, concomitant cancer diagnoses, end-of-life palliative care, preoperative radiation, or missing primary outcome variable (readmission) were excluded from the data set (Figure 1). Additionally, patients who died within 30 days of surgery or whose vital status was unknown were excluded; this was done in an attempt to exclude patients who died during their index hospitalization since they would not be at risk for subsequent readmission. After all inclusion and exclusion criteria were met, 19,711 cases remained available for analysis. Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Emory University.

Figure 1.

Patient Inclusion and Exclusion Algorithm

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics for each variable were reported, which are presented as mean values with standard deviations or as counts with percentages. All data are complete except where noted within the text or footnotes of tables. The univariate association of each covariate with readmission was assessed using the chi-square test for categorical covariates and ANOVA for numerical covariates.

Multivariable logistic regression was then used to model readmission. All covariates were entered into the model and backward selection with an alpha = 0.20 criteria for removal from the model was used. All statistical tests were two-sided, with the alpha threshold of significance set at 0.05.Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS Version 9.3 (Cary, NC) and SAS macro developed by Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource at Winship Cancer Institute.16

RESULTS

The majority of patients were female (n=10,820; 54.9%) and Caucasian (n=17,229; 88.1%), with a mean age of 66.6 (±10.2) years. Approximately half of all patients (n=9,830; 49.9%) had one or more co-existing medial comorbidities. Most patients lived in a metro area (n=14,786; 80.5%) and carried a form of government insurance (n=12,497; 64.1%). Education and income levels varied widely throughout the study cohort (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study Cohort Demographics

| Variable* | N=19,711 | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 10,820 | 54.9 |

| Age, years (Mean, SD) | 66.6 | ±10.2 | |

| Charlson/Deyo Comorbidity Score | 0 | 9,881 | 50.1 |

| 1 | 7,049 | 35.8 | |

| 2+ | 2,781 | 14.1 | |

| Race | White | 17,229 | 88.1 |

| Insurance Status | Not insured | 444 | 2.3 |

| Private insurance | 6,568 | 33.7 | |

| Government insurance | 12,497 | 64.1 | |

| Income | <$30,000 | 2,556 | 13.8 |

| $30,000–$34,999 | 3,508 | 18.9 | |

| $35,000–$45,999 | 5,331 | 28.8 | |

| $46,000+ | 7,126 | 38.5 | |

| Education | ≥29% | 3,065 | 16.5 |

| 20–28.9% | 4,569 | 24.7 | |

| 14–19.9% | 4,718 | 25.5 | |

| <14% | 6,168 | 33.3 | |

| Geographic Setting | Metro Area | 14,786 | 80.5 |

| Urban | 3,128 | 17.0 | |

| Rural | 452 | 2.5 |

SD (standard deviation)

Data incomplete for the following variables: race(n=163), insurance status(n=202), income(n=1190), education(n=1191), and geographic setting(n=1345)

More than two-thirds of cases were accomplished via thoracotomy (n=13,920; 70.6%). Approximately one third of cases were performed at an academic or research institution (n=6,762; 34.3%). Median postoperative length of stay was 6 days, and a total of 840 (4.3%) patients had an unplanned readmission within 30 days following lobectomy for their early stage lung cancer (Table 3).

Table 3.

Operative and Postoperative Variables

| Variable* | N=19,711 | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative | |||

| Surgical Approach | Thoracotomy (Open) | 13,920 | 70.6 |

| VATS | 5,791 | 29.4 | |

| Facility Type | Academic/Research Program (Includes NCI) | 6,762 | 34.3 |

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Program | 11,454 | 58.1 | |

| Community Cancer Program/Other | 1,495 | 7.6 | |

| Tumor Size, cm (Mean, SD) | 2.83 | ±2.3 | |

| Surgical Margin Positive | 482 | 2.5 | |

| Postoperative | |||

| Postoperative Length of Stay, Days (Median) |

6 | ||

| Unplanned | 30-day Readmission | 840 | 4.3 |

Data incomplete for the following variables: tumor size(n=35), surgical margin(n=81), and postoperative length of stay(n=828)

VATS: Video-assisted thoracic surgery

SD: Standard Deviation

LN: Lymph node

Male patients were more likely to be readmitted compared to female patients (4.9 vs. 3.8%, p<0.001), as were those who received their surgery at a non-academic facility vs. an academic one (4.6 vs. 3.6%; p=0.001). Readmitted patients also had more underlying medical comorbidities (Charlson/Deyo Score 1+ vs. 0; 4.8 vs. 3.7%; p<0.001) and had a longer median hospital LOS; (6 vs. 5 days). Patients who were readmitted were from a lower income bracket and more likely to either be uninsured or carry government insurance (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate Association with Unplanned Readmission

| Unplanned Readmission? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Level |

No N=18871 |

Yes N=840 |

P-valuea |

| Surgical Approach, n(%) | Open | 13,374(96.1) | 546(3.9) | <.001 |

| Minimally Invasive (VATS) | 5497(94.9) | 294(5.1) | ||

| Facility Type | Community Cancer Program/Other | 1424(95.3) | 71(4.8) | 0.006 |

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Program | 10,930 (95.4) | 524(4.6) | ||

| Academic/Research Program (Includes NCI) | 6517(96.4) | 245(3.6) | ||

| Sex | Male | 8459(95.1) | 432(4.9) | <.001 |

| Female | 10,412(96.2) | 408(3.8) | ||

| Age, years (Mean, SD) | 66.56(±10.2) | 67.06(±9.9) | 0.165 | |

| Race: White | No | 2229(96.1) | 90(3.9) | 0.310 |

| Yes | 16,482(95.7) | 747(4.3) | ||

| Insurance | Not Insured | 424(95.5) | 20(4.5) | 0.015 |

| Private Insurance | 6326(96.3) | 242(3.7) | ||

| Govt. Insurance | 11,925(95.4) | 572(4.6) | ||

| Income | <$30,000 | 2436(95.3) | 120(4.7) | 0.046 |

| $30,000–$34,999 | 3338(95.2) | 170(4.9) | ||

| $35,000–$45,999 | 5095(95.6) | 236(4.4) | ||

| $46,000+ | 6855(96.2) | 271(3.8) | ||

| Education | >=29% | 2915(95.1) | 150(4.9) | 0.105 |

| 20–28.9% | 4358(95.4) | 211(4.6) | ||

| 14–19.9% | 4526(95.9) | 192(4.1) | ||

| <14% | 5924(96.0) | 244(4.0) | ||

| Urban/Rural | Metro Area | 14,127(95.5) | 659(4.5) | 0.118 |

| Urban | 3006(96.1) | 122(3.9) | ||

| Rural | 439(97.12) | 13(2.88) | ||

| Charlson/Deyo Score | 0 | 9516(96.31) | 365(3.69) | <.001 |

| 1+ | 9355(95.17) | 475(4.83) | ||

| Tumor Size, cm (Mean, SD) | 2.83(±2.3) | 2.89(±2.6) | 0.466 | |

| Postoperative Length of Stay, Days (Median) |

6 | 5 | <.001 | |

Parametric p-value calculated by ANOVA for numerical covariates and chi-square test for categorical covariates

Multivariable logistic regression analysis identified that male gender (OR 1.23; CI 1.07–1.43), one or more pre-existing medical comorbidities (OR 1.23; CI 1.06–1.42), and median household income level<$46,000 were all significantly associated with higher risk of readmission (Table 5). Private insurance status (OR 0.79; CI 0.67–0.93), urban (OR 0.71; CI 0.57–0.88) or rural (OR 0.47; CI 0.26–0.84) geographic residence, and academic/research facility type (OR 0.75; CI 0.56–1.01) all appeared to have a protective effect against readmission. Operative approach (VATS vs. Open) remained a significant variable predicting higher readmission rates in both univariate (5.1 vs. 3.9%, p<0.001) and multivariable analysis (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.2–1.65).

Table 5.

Multivariable Association with Unplanned Readmissiona

| Covariate | Level | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

OR P- value |

Type3 P- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical Approach | Minimally Invasive (VATS) | 1.42(1.21–1.65) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Open | - | |||

| Facility Type | Academic/Research Program (Includes NCI) | 0.75(0.56–1.01) | 0.061 | 0.004 |

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Program | 0.99(0.75–1.30) | 0.952 | ||

| Community Cancer Program/Other | - | |||

| Sex | Male | 1.23(1.07–1.43) | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| Female | - | |||

| Race: White | Yes | 1.23(0.97–1.57) | 0.091 | 0.091 |

| No | - | |||

| Insurance | Not Insured | 1.00(0.62–1.60) | 0.991 | 0.016 |

| Private Insurance | 0.79(0.67–0.93) | 0.004 | ||

| Govt. Insurance | - | |||

| Income | <$30,000 | 1.51(1.18–1.92) | <.001 | 0.002 |

| $30,000–$34,999 | 1.38(1.12–1.71) | 0.003 | ||

| $35,000–$45,999 | 1.23(1.03–1.48) | 0.025 | ||

| $46,000+ | - | |||

| Urban/Rural Residence | Rural | 0.47(0.26–0.84) | 0.011 | <.001 |

| Urban | 0.71(0.57–0.88) | 0.002 | ||

| Metro Area | - | |||

| Charlson/Deyo Score | 1+ | 1.23(1.06–1.42) | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| 0 | - |

Number of observations in the original data set =19711. Number of observations used =17708 (cases with missing variables excluded). Backward selection with an alpha level of removal of 0.2 was used. The following variables were removed from the model: Patient Age, Education, Year of Diagnosis, Primary Site, and Tumor size.

Study demographics and median postoperative LOS based on operative approach and readmission status is shown in Table 6 and Table 7, respectively. There were no significant differences in race or comorbidity status based on operative approach. Regardless of operative approach, readmitted patients had a longer median LOS during their index hospitalization; however, the VATS cohort had a total length of stay that was one day shorter than the open cohort, even if they were readmitted.

Table 6.

Demographics by Operative Approach

|

Open N=13,920 |

VATS N=5,791 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n(%) | n(%) | P-value | |

| Sex | Female | 7,529(54.1) | 3,291(56.8) | <.001 |

| Age, years (Mean, SD) | 66.5(±10.2) | 66.8(±10.0) | 0.100 | |

| Charlson/Deyo Comorbidity Score | 0 | 6,945(49.9) | 2,936(50.7) | 0.302 |

| 1+ | 6,975(50.1) | 2,855(49.3) | ||

| Race | White | 12,170(88.1) | 5,059(88.2) | 0.866 |

| Insurance Status | Not insured | 329(2.4) | 115(2.0) | 0.023 |

| Private insurance | 4,562(33.2) | 2,006(34.9) | ||

| Government insurance | 8,870(64.5) | 3,627(63.1) | ||

| Income | <$30,000 | 1,884(14.4) | 672(12.4) | <.001 |

| $30,000–34,999 | 2,574(19.6) | 934(17.3) | ||

| $35,000–$45,999 | 3,875(29.6) | 1,456(26.9) | ||

| $46,000+ | 4,778(36.4) | 2,348(43.4) | ||

| Education | ≥29% | 2,256(17.2) | 809(15.0) | <.001 |

| 20–28.9% | 3,394(25.9) | 1,175(21.7) | ||

| 14–19.9% | 3,324(25.4) | 1,394(25.8) | ||

| <14% | 4,136(31.6) | 2,032(37.6) | ||

| Geographic Setting | Metro Area | 10,281(79.3) | 4,505(83.5) | <.001 |

| Urban | 2,340(18.0) | 788(14.6) | ||

| Rural | 352(2.7) | 100(1.9) |

SD: standard deviation

Table 7.

Median Length of Stay by Operative Approach and Readmission Status

| Operative Approach |

Yes (N=840) |

No (N=18,871) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open | 7 days (n=536) |

6 days (n=12,742) |

<0.001 |

| VATS | 6 days (n=294) |

5 days (n=5311) |

<0.001 |

COMMENT

In 2001, a full decade before readmissions started becoming so highly scrutinized, Handy and colleagues were the first to publish a series focused on identifying risk factors for readmission following lung surgery.17 The authors concluded that the only significant risk factor for readmission was the type of procedure itself (pneumonectomy), and specifically noted that patient age, gender, diagnosis, comorbidities, LOS, or postoperative complications were not risk factors. Twelve years later, a retrospective study of lobectomy patients of a single healthcare system concluded that age and hospital LOS were the only significant factors increasing the risk of postoperative readmission.6

A 2014 study using SEER-Medicare data concluded that male gender, age >75 years, regional population density, procedure type, and comorbidities (acute MI, CHF, COPD, diabetes, renal failure, and induction chemo-radiation therapy) all significantly increased the risk of readmission following surgical resection of lung cancer.13 While the study included all procedure types (ranging from pneumonectomy to VATS wedge resection) and all stages of lung cancer, it was the first study to highlight the potential for numerous preoperative risk factors leading to readmission in lung cancer patients. In 2016, a study analyzing California, Florida and New York state inpatient databases identified that male gender, government insurance, and COPD significantly increase the risk of readmission following lobectomy.18

The current study reveals that male gender, pre-existing medical comorbidity, median household income level, insurance status (government vs. private), geographic residence (metro vs. urban vs. rural), facility type (academic vs. community) all exerted significant influence on unplanned 30-day readmissions. Of interest, we found that age and race were not significantly associated with readmission, a result that differs from previous studies within the literature.6,9,10,13 On the other hand, similar to previously reported series, our results confirm that male gender, pre-existing comorbidity, lack of private insurance and geographic area of patient residence remain important preoperative characteristics associated with increased risk of readmission.13,18 The current series is the first within the literature to report that lower income level and surgery at a non-academic/research facility are additional significant preoperative factors associated with readmission.

Socioeconomic variables have all been analyzed in a variety of other cancers, including lung cancer, and have been shown to have significant impact on survival.19–23 As highlighted by both our study results and those that have been previously published, socioeconomic factors are now starting to be recognized as important preoperative indicators for increased risk of hospital readmission.9,10,13,23 Although SES factors are non-modifiable in and of themselves, they have been repeatedly linked with poor outcomes, including readmission.24 Reasons for this finding have included patient preference for hospitalization versus ambulatory care and lack of access to follow-up visits.25 To improve outcomes, extensive research has been done to identify interventions that are most effective in this and other patient populations to reduce readmission rates.26 While many of these interventions have not been applied specifically to thoracic surgery for lung cancer, they include targeted strategies to reduce readmissions following vascular surgery,27,28 cardiac surgery,29,30 colorectal surgery,31 and general medicine patients.32 Future studies should investigate such interventions in patients undergoing lobectomy for NSCLC.

Because operative approach is an important aspect of preoperative decision-making, we considered it an important variable within our analysis. The current data indicate that operative approach (VATS vs. Open) remained a significant variable associated with readmission in both univariate (5.1 vs. 3.9%, p<0.001) and multivariable analysis (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.2–1.65). While operative approach has been associated with risk of readmission in numerous series within the literature, it is usually the open or more invasive approach that is the significant variable.13,17 It is well documented that minimally invasive surgeries are associated with shorter LOS and fewer postoperative complications across nearly all surgical sub-specialties, and as a result, it is intuitive that such operative approaches would be associated with fewer readmissions.

In our series, the minimally invasive approach (VATS) was associated with a 40% increased likelihood of readmission. One might postulate that patients undergoing VATS are likely to be older and sicker than those undergoing thoracotomy; however, our analysis shows no such difference between the cohorts based on operative approach (Table 6). Furthermore, patients undergoing VATS are more likely to be female, have private insurance, earn higher income, have higher education levels, and reside in metropolitan areas than patients undergoing open thoracotomy, and based on our analysis, all such variables should in theory be protective against readmission. It is possible that patients undergoing VATS may be placed on an enhanced recovery protocol with the goal of expedited hospital discharge. It could be speculated that patients are being discharged too soon following VATS, thus leading to increased risk of readmission. Interestingly, however, a recent retrospective study from Madani and colleagues examined outcomes before and after the implementation of an enhanced recovery pathway following open lobectomy and concluded that although LOS is significantly shorter, there was no difference with regards to both complication and readmission rate.33 There is not such data for VATS patients, and it is an area that deserves more attention.

Several recent series have concluded that hospital readmission following lobectomy is not affected by surgical approach. A retrospective, single-institution analysis of 213 patients undergoing lobectomy reports that 9% of VATS patients and 14% of thoracotomy patients were readmitted (p=0.3).34,35A second study examining 1,847 pulmonary resection patients from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database also reports that surgical approach was not associated with increased risk of readmission (HR 1.07; 95% CI 0.75–1.52).27 Conversely, a cohort study utilizing an insurance claims database (MarketScan) examined 9,962 lobectomies and reported a significantly lower rate of readmission for VATS vs. open approach (10 vs. 12%, p=0.03).36 Finally, similar to our results, a recent NCDB study comparing outcomes of minimally invasive lobectomy [both VATS (n=7,824) and robotic (n=2,025)] also concluded that readmission was higher following a minimally invasive approach (5% vs. 4% for open; p<0.01).37 Given the differences these data, combined with the results from the current study, prospective studies are needed with regards to VATS vs. open lobectomy as a risk factor for hospital readmission.

The current study has several limitations that deserve to be highlighted. First, it is a retrospective analysis of a de-identified dataset, and thus there are unmeasured confounding variables influencing the results of our analysis. Second, the NCDB only captures readmissions to the same hospital where the surgical procedure was performed and thus readmissions to other hospitals are not included in analysis. Third, the reason for readmission is not available within NCDB and thus we cannot draw any conclusions as to specifically why patients are being readmitted. Fourth, socioeconomic factors are derived using census tract data, and while it is considered an acceptable surrogate for estimating a patient’s income and education level, it is limited in capturing the specific socioeconomic status of each individual patient. Prospective studies will be needed to analyze the impact of socioeconomics upon hospital readmission following surgery for lung cancer.

Despite these weaknesses, utilizing the NCDB allows for analysis of a large generalizable national dataset that include more contemporary data than the National Cancer Institute’s SEER analysis.38 Specifically, the NCDB has accrued nearly 120,000 cases of primary lung cancer, a number which is significantly higher than SEER, and contains greater patient diversity in terms of geography, patient age, and surgeon specialty training than Medicare and STS databases.38,39 As a result, these data are felt to be widely applicable to surgeons in a variety of settings, and particularly relevant in light of current healthcare reform.

CONCLUSION

In addition to clinical and procedure-related variables, the current study suggests that socioeconomic factors need to be considered in regards to identifying patients who are at risk for postoperative readmission following lobectomy for early stage lung cancer. Male patients with medical comorbidities, as well as those without private insurance and who reside in lower-income and metropolitan areas should be considered more-likely to be readmitted within 30 days of surgery. Awareness of these risk factors is important for preoperative planning and allocation of limited resources to help prevent hospital readmissions in this patient population. Examples of potential interventions include improved pre-operative patient education and more careful post-operative discharge planning, including possible home health follow-up. Future studies should aim to develop risk-calculators for use in the preoperative setting, with the goal of preventing unplanned readmissions, decreasing healthcare spending, and, most importantly, improving the quality of care for our patients.

Acknowledgments

Set acknowledgement: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and NIH/NCI under award number P30CA138292. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Data used in the study are derived from a de-identified NCDB file. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology used, or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the Forty-first Annual Meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association, Whistler, BC, Canada, June 24–27, 2015.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Stat. 2010;119:318–319. Pub L. No. 111–148, §2702, 124. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program Supplemental Data File. [Accessed 26 April 2015];Inpatient Prospective Payment System, FY. 2013 Available online: http://www.cms.gov.

- 3.Kassin MT, Owen RM, Perez SD, et al. Risk factors for 30-day hospital readmission among general surgery patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2012;215:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merkow RP, Ju MH, Chung JW, et al. Underlying reasons associated with hospital readmission following surgery in the United States. Jama. 2015;313:483–495. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.18614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawson EH, Hall BL, Louie R, et al. Association between occurrence of a postoperative complication and readmission: implications for quality improvement and cost savings. Annals of surgery. 2013;258:10–18. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828e3ac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman RK, Dilts JR, Ascioti AJ, Dake M, Mahidhara RS. A comparison of length of stay, readmission rate, and facility reimbursement after lobectomy of the lung. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2013;96:1740–1745. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.06.053. discussion 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Cai X, Mukamel DB, Cram P. Impact of length of stay after coronary bypass surgery on short-term readmission rate: an instrumental variable analysis. Medical care. 2013;51:45–51. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318270bc13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider EB, Hyder O, Brooke BS, et al. Patient readmission and mortality after colorectal surgery for colon cancer: impact of length of stay relative to other clinical factors. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2012;214:390–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.025. discussion 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girotti ME, Shih T, Revels S, Dimick JB. Racial disparities in readmissions and site of care for major surgery. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2014;218:423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Joynt KE. Disparities in surgical 30-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. Annals of surgery. 2014;259:1086–1090. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. Jama. 2011;305:675–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Gawande AA, Jha AK. Variation in surgical-readmission rates and quality of hospital care. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369:1134–1142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1303118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu Y, McMurry TL, Isbell JM, Stukenborg GJ, Kozower BD. Readmission after lung cancer resection is associated with a 6-fold increase in 90-day postoperative mortality. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2014;148:2261–2267. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer Accreditation Categories. [Accessed 26 April 2015]; Available at: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/accredited/about/categories. [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. [Accessed 26 April 2015]; Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.

- 16.Nickleach D, Liu Y, Shrewsberry A, Ogan K, Kim S, Wang Z. SESUG 2013: The Proceedings of the SouthEast SAS Users Group. St. Pete Beach, FL: 2013. SAS® Macros to Conduct Common Biostatistical Analyses and Generate Reports. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Handy JR, Jr, Child AI, Grunkemeier GL, et al. Hospital readmission after pulmonary resection: prevalence, patterns, and predisposing characteristics. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2001;72:1855–1899. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03247-7. discussion 9–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stiles BM, Poon A, Giambrone GP, et al. Incidence and Factors Associated With Hospital Readmission After Pulmonary Lobectomy. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2016;101:434–443. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hole DJ, McArdle CS. Impact of socioeconomic deprivation on outcome after surgery for colorectal cancer. The British journal of surgery. 2002;89:586–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smigal C, Jemal A, Ward E, et al. Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity: update 2006. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2006;56:168–183. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu CC, Hsu TW, Chang CM, Yu CH, Wang YF, Lee CC. The effect of individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status on gastric cancer survival. PloS one. 2014;9:e89655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khullar OV, Gillespie T, Nickleach DC, et al. Socioeconomic risk factors for long-term mortality after pulmonary resection for lung cancer: an analysis of more than 90,000 patients from the National Cancer Data Base. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2015;220:156–168. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez FG, Khullar O, Force SD, et al. Hospital readmission is associated with poor survival after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2015;99:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glance LG, Kellermann AL, Osler TM, Li Y, Li W, Dick AW. Impact of Risk Adjustment for Socioeconomic Status on Risk-adjusted Surgical Readmission Rates. Annals of surgery. 2016;263:698–704. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Long JA, Shannon R, Grande D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1196–1203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eun JC, Nehler MR, Black JH, 3rd, Glebova NO. Measures to reduce unplanned readmissions after vascular surgery. Semin Vasc Surg. 2015;28:103–111. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brooke BS, De Martino RR, Girotti M, Dimick JB, Goodney PP. Developing strategies for predicting and preventing readmissions in vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.03.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bates OL, O'Connor N, Dunn D, Hasenau SM. Applying STAAR interventions in incremental bundles: improving post-CABG surgical patient care. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11:89–97. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nabagiez JP, Shariff MA, Khan MA, Molloy WJ, McGinn JT., Jr Physician assistant home visit program to reduce hospital readmissions. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2013;145:225–231. 33. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.09.047. discussion 32–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagle D, Pare T, Keenan E, Marcet K, Tizio S, Poylin V. Ileostomy pathway virtually eliminates readmissions for dehydration in new ostomates. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1266–1272. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31827080c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balaban RB, Galbraith AA, Burns ME, Vialle-Valentin CE, Larochelle MR, Ross-Degnan D. A Patient Navigator Intervention to Reduce Hospital Readmissions among High-Risk Safety-Net Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:907–915. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3185-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madani A, Fiore JF, Jr, Wang Y, et al. An enhanced recovery pathway reduces duration of stay and complications after open pulmonary lobectomy. Surgery. 2015;158:899–908. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.04.046. discussion-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Assi R, Wong DJ, Boffa DJ, et al. Hospital readmission after pulmonary lobectomy is not affected by surgical approach. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2015;99:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajaram R, Ju MH, Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, DeCamp MM. National evaluation of hospital readmission after pulmonary resection. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farjah F, Backhus LM, Varghese TK, et al. Ninety-day costs of video-assisted thoracic surgery versus open lobectomy for lung cancer. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2014;98:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang CF, Sun Z, Speicher PJ, et al. Use and Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Lobectomy for Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in the National Cancer Data Base. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2016;101:1037–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosen JE, Hancock JG, Kim AW, Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ. Predictors of mortality after surgical management of lung cancer in the National Cancer Database. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2014;98:1953–1960. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lerro CC, Robbins AS, Phillips JL, Stewart AK. Comparison of cases captured in the national cancer data base with those in population-based central cancer registries. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1759–1765. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2901-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]