Abstract

Glioblastoma multiform (GBM) is the most common malignant glioma of all the brain tumors and currently effective treatment options are still lacking. GBM is frequently accompanied with overexpression and/or mutation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which subsequently leads to activation of many downstream signal pathways such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/rapamycin-sensitive mTOR-complex (mTOR) pathway. Here we explored the reason why inhibition of the pathway may serve as a compelling therapeutic target for the disease, and provided an update data of EFGR and PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors in clinical trials.

Keywords: glioblastoma, EGFR, PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, targeted therapy

INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma multiform

Glioblastoma multiform (GBM), WHO grade IV, is the most common and aggressive glioma of all primary brain tumors, exhibiting a high rate of recurrence and poor prognosis due to the invasive nature of the tumor [1, 2]. Considering the location and diffusely infiltrating nature of the tumor, complete surgical resections are challenging. Standard therapy for GBM is radiation plus the chemopeutic agent temozolomide (TMZ). The cytotoxicity of TMZ is thought to be primarily due to alkylation of DNA hence leading to DNA damage and tumor cell death [3]. However, the activation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway leads to the development of drug resistance thereby dampening the therapeutic effect of TMZ [4]. The five year survival rate for glioblastoma is less than 5% in adults [5-7]. The occurrence of GBM is frequently associated with molecular changes in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/rapamycin-sensitive mTOR-complex (mTOR) pathways. The frequency of genetic alterations such as overexpression EGFR, activating mutations of PI3CA (p110) or PIK3R1 (P85), or loss of PTEN expression has been estimated to around 88% [8-12]. GBM patients with an activated PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway also have poor prognosis than patients without oncogenic activation of the pathway [13]. Therefore, inhibitors targeting EGFR and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway have emerged as potential treatment for GBM [14-18]. Currently, a series of inhibitors targeting EGFR and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway are evaluated in preclinical and clinical studies as single agent or in combination with the traditional treatment [19]. It is of particular interest to explore whether those inhibitors are effective to restore the therapeutic sensitivity.

EGFR and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signal transduction pathway

EGFR is a type of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), playing a central role in cell division, migration, adhesion, differentiation and apoptosis [20, 21]. EGFR comprises of extracellular ligand binding domain, transmembrane domain and intracellular tyrosine kinase domain. Upon binding to various of ligands, such as EGF and TGFα, EGFR is activated through homodimerization or heterdimerization on the cell surface and subsequently leads to the phosphorylation of its intracellular tyrosine kinase domain [22]. The activation of EGFR results in activation of multiple downstream signal transduction pathways such as PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway [23].

Members of the PI3K family are lipid kinases involved in multiple cellular process, including proliferation, differentiation, migration, metabolism and survival [24]. PI3K is generally classified into three classes according to their substrate specificity and subsequence homology, among which, the class I is most vital to the tumorigenesis. Class I consisted of a catalytic subunit p110 (α, β, γ) and a regulator subunit p85. A fourth p110 isoform (p110δ) is paired with the p101 regulatory subunit in class IB PI3Ks. Upon ligand binding, phosphorylated tyrosine residing in activated RTKs will bind to p85. The subsequent conformation change will release the catalytic subunit p110 [25], where activated p110 phosphorylated the phosphatidy-linositol-3, 4-bisphosphate (PIP2) into the second messenger phosphatidylinositol-3, 4, 5-bisphosphate (PIP3). This reaction can be reversed by the PI3K antagonist PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten) [26]. Subsequently, PIP3 will recruit the downstream Akt to inner membranes and phosphorylates Akt on its serine/threonine kinasesites (Thr308 and Ser473) [27, 28]. Activated Akt is involved in the downstream mTORC1 mediated response to biogenesis of protein and ribosome.

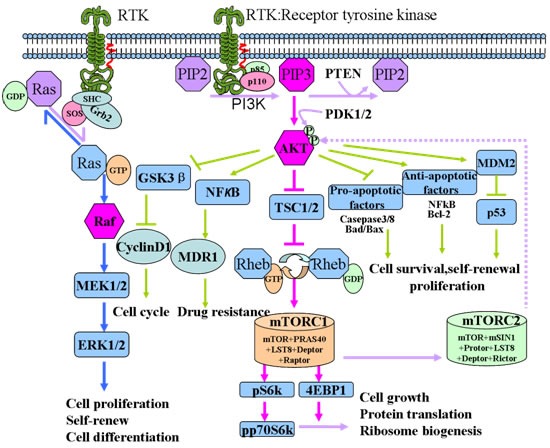

In PI3K pathway, mTOR acts as both a downstream effector and an upstream regulator [29, 30]. mTOR resides in rapamycin-sensitive mTOR-complex (mTORC1) and a rapamycin-insensitive complex (mTORC2) [31, 32]. The activated Akt inhibits tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) 1/2 activity, thereby initiate the mTORC1-mediate signaling pathway, involving in the phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 kinase (pS6k), eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) and eukaryotic initiation factor binding protein 1(4EBP1), which participate in protein translation, ribosome biogenesis as well as cell growth [33, 34]. The mTORC2 phosphorylates Akt at Ser-473, and then further takes part in cell survival, metabolism, proliferation, and cytoskeletal organization [31, 35]. Within PI3K signaling pathway, another important molecule is PTEN. As clinical research revealed, the EGFR or PTEN mutation would lead to continuous activation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, thereby contributing to the tumorigenesis and cancer therapy resistance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway.

Upon relevant ligand binding, RTK, such as EGFR, is activated and subsequently inducing a series of cascade reaction. First, the regulator subunits of PI3K, p85, dimerize and release its catalytic subunit p110. p110 enables the membrane protein PIP2 to phosphorylate into PIP3. PIP3 begins to recruit the downstream Akt to inner membranes and phosphorylated the serine/threonine kinase (Thr308 and Ser473) sites by phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1/2 (PDK1/2). Activated Akt is involved in the downstream mTORC1 mediated response to biogenesis of protein and ribosome. Besides that, activated Akt is also involved in the regulation of cell cycle and pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic factors mediated choices of cell apoptosis and survival. Additionally, it is also involved in the NFκB/MDR1 mediated drug resistance.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF TARGETED THERAPY TOWARDS EGFR AND PI3K/AKT/MTOR

EGFR inhibitors

EGFR alteration, including overexpression or gene amplification, is the most frequent form of genetic mutation, occurred in 40-50% of glioblastomas [36, 37]. Logically, EGFR is a promising target for the treatment of GBM. Though promising results was shown in preclinical data, targeting EGFR in clinical trials revealed marginal effects. An overview of ongoing clinical trial in GBM is summarized in Table 1. Information about clinical trials has been retrieved from www.clinicaltrials.gov. In the clinical trial NCT00250887, the effectiveness of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor Gefitinib was tested in recurrent glioblastoma. Though EGFR was successfully -dephosphorylated, the downstream target remains constitutively active. Therefore the effectiveness was unsatisfactory [38]. Erlotinib, another selective EGFR inhibitor, also showed minimal effect to treat the recurrent glioblastoma (NCT00086879) [39]. Other than single agent treatment, combination therapy was also explored. When Erlotinib was combined with TMZ and radiotherapy in a phase I/II trial, no sign of benefit was showed compared with TMZ controls (NCT00039494) [40, 41]. Additionally, the combination therapy of Erlotinib with VEGF antibody also shows no obvious survival benefit [42]. The failure of targeting EGFR is generally due to the hyperactivation of downstream PI3K/Akt signaling, so the downstream components represents an attractive target for the treatment of malignant brain tumors.

Table 1. Ongoing clinical trials in brain tumors targeting EGFR.

| Drug | Targets | Combination Partner | Patient group | Phase | State | Trail ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gefitinib | EGFR | recurrent glioblastoma | II | completed | NCT00250887 | |

| EGFR | GBM | II | completed | NCT00014170 | ||

| EGFR | GBM | II | completed | NCT00016991 | ||

| EGFR | brain and central nervous system tumors | II | completed | NCT00025675 | ||

| EGFR | radiation | GBM | I/II | completed | NCT00052208 | |

| EGFR | radiation | GBM | II | completed | NCT00238797 | |

| Gefitinib, Temozolomide | EGFR | brain and central nervous system tumors | I | completed | NCT00027625 | |

| Gefitinib, Irinotecan | EGFR, topoismerase I | refractory solid tumor | I | completed | NCT00132158 | |

| Erlotinib | EGFR | GBM | II | completed | NCT00337883 | |

| EGFR | GBM | II | unknown | NCT00054496 | ||

| EGFR | GBM and other brain tumors | I/II | ongoing | NCT00045110 | ||

| EGFR | GBM | I/II | completed | NCT00301418 | ||

| EGFR | radiation | brain/central nervous system tumors | I/II | completed | NCT00124657 | |

| EGFR | cytoreductive surgery | recurrent malignant gliomas | ongoing | NCT01257594 | ||

| Erlotinib, Temozolomide | EGFR | radiation | GBM, gliosarcoma | II | completed | NCT00187486 |

| EGFR | radiation | GBM | II | completed | NCT00274833 | |

| EGFR | radiation | GBM | II | completed | NCT00039494 | |

| Erlotinib, Temozolomide, Carmustine | EGFR | glioblastoma, gliosarcoma | II | completed | NCT00086879 | |

| Erlotinib, Bevacizumab. | EGFR, VEGF | glioblastoma, gliosarcoma | II | completed | NCT00671970 | |

| Erlotinib, Bevacizumab, Temozolomide | EGFR, VEGF | radiation | GBM | II | ongoing | NCT00720356 |

| Erlotinib, Sorafenib | EGFR, RAF, VEGFR | GBM | II | completed | NCT00445588 | |

| Erlotinib, Dasatinib | EGFR, SRC | GBM | I | completed | NCT00609999 | |

| Dacomitinib | EGFR | recurrent glioblstoma | II | ongoing | NCT01520870 | |

| Afatinib | EGFR | refractory solid tumors | II | completed | NCT00875433 | |

| AEE788 | EGFR | GBM | I/II | completed | NCT00116376 | |

| Lapatinib | EGFR | GBM | I/II | completed | NCT00099060 | |

| Lapatinib | EGFR | malignant brain tumors | II | completed | NCT00107003 | |

| Nimotuzumab | EGFR | GBM | completed | NCT00561873 | ||

| Nimotuzumab, Temozolomide | EGFR | radiation | GBM | III | completed | NCT00753246 |

| EGFR Bi-armed Autologous T cells | EGFR, CD3 | glioblastoma, gliosarcoma recurrent neoplasm | I/II | not yet recruiting | NCT02521090 | |

| AMG 595 | EGFR | GBM | I | ongoing | NCT01475006 | |

| Sym004 | EGFR | recurrent glioblastoma | II | ongoing | NCT02540161 | |

| Cetuximab, Temozolomide | EGFR | radiation | GBM | I/II | unknown | NCT00311857 |

| Cetuximab, Bevacizumab, Irinotecan | EGFR, VEGF, topoismerase I | GBM | II | completed | NCT00463073 | |

| Afatinib, Temozolomide | EGFR | radiation | GBM | I | ongoing | NCT00977431 |

| Afatinib, Temozolomide | EGFR | GBM | II | ongoing | NCT00727506 |

Clinical data related to the EGFR was searched until Nov, 2015.

PI3K inhibitors

Currently, the PI3K inhibitors as a single agent or combined with other therapies are being tested in a number of clinical trials (Table 2) [43]. There are pan-PI3K inhibitors and isoform specific PI3K inhibitors [14]. The first generation of pan-PI3K inhibitors is represented by wortmannin and LY294002 [44, 45]. They have showed anti-cancer effect in vivo and in vitro [46-49]. However, both drugs were halted at preclinical studies due to the toxicity, poor pharmacodynamics and selectivity. A new generation of PI3K inhibitors, BKM120 and PX-866, exhibit better drug properties such as high stability and low side effects [50, 51]. BKM120 has anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic activity in a number of tumor cell lines, human tumor xenograft models and cancer patients bearing PI3K activating mutations [52]. BKM120 was smoothly passed phase I clinical trial and now is undergoing phase II trial among patients with recurrent glioblastoma and activated PI3K pathway (NCT01339052) (Table 2) [50]. At present, BKM120 is also undergoing several clinical trials in combination with radiation (NCT01473901), anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody Bevacizumab (NCT01349660), LDE225 (NCT01576666) and INC280 (NCT01870726) [53]. PX-866 could bind with the catalytic domain of ATP and it acts as an irreversible inhibitor. Though PX-866 could increase median survival time of the animals and show significant anti-tumor activity in GBM xenograft models [54, 55], the recent completed clinical study showed the overall response rate was low (NCT01259869) [56].

Table 2. Ongoing clinical trials in brain tumors targeting PI3K.

| Drug | Targets | Combination partner | Patient group | Phase | State | Trail ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BKM120 | Pan-PI3K | surgery | recurrent glioblastoma | II | ongoing, | NCT01339052 |

| Bevacizumab | relapsed/refractory GBM | I/II | recruiting | NCT01349660 | ||

| LDE225 | advanced solid tumor | I | completed | NCT01576666 | ||

| INC280 | recurrent glioblastoma | I/II | recruiting | NCT01870726 | ||

| BKM120, Temozolomide | Pan-PI3K | radiation | glioblastoma | I | ongoing | NCT01473901 |

| PX-866 | Pan-PI3K | GBM | II | completed | NCT01259869 |

Clinical data related to the EGFR was searched until Nov, 2015.

Akt inhibitors

Akt is a central player in the EGFR/PI3K signaling pathways. Evidence shows that Akt play an important role in tumor proliferation and radiosensitivity [57]. One of the most promising Akt inhibitor, perifosine, inhibits Akt activity by preventing its translocation to the cell membrane [58, 59]. Currently, perifosine is being clinically tested in a number of different cancers [60, 61]. Perifosine has several drawbacks such as limited ability to penetrate blood-brain-barrier (BBB) and gastrointestinal side effects. A phase II trial of perifosine in recurrent GBM was ongoing but only marginal effect was shown (NCT00590954).

mTOR inhibitors

As downstream targets of phosphorylated Akt, inhibition of mTOR would also be another therapeutic approach to reduce the effects of constitutively activate Akt in GBM. mTORC1 inhibitors mainly contain rapamycin (sirolimus) and its analogues, such as RAD001 (everolimus), CCL-779 (temsirolimus) and AP23573 (ridaforolimus) [62]. Rapamycin inactivate mTORC1 through altering the conformation of the kinase. Though rapamycin and its analogues exhibit efficacy of mTOR inhibitors in both in vitro and in vivo models [63, 64], they would arose hyperactivation of Akt and mTORC2 by some feedback loop and pathway crosstalk [65]. Rapamycin shows anti-tumor activity in a phase I trial for patients with recurrent PTEN-deficient glioblastoma (NCT00047073) [66]. Unfortunately, phase II clinical trials for rapamycin analogs fail to achieve promising results (NCT00515086, NCT00016328, NCT00022724, and NCT00087451) [67-71]. The limited efficacy might result from the feedback loops and crosstalk with other pathways. Recently, more exploration was focusing on the combination treatment of rapamycin analogs with other modalities [71]. The combination of EGFR inhibitor erlotinib with sirolimus or temsirolimus was tested in clinical trials (NCT00112736 and NCT0062243). However, either of trial shows promising results [72, 73]. A phase II study of everolimus with bevacizumab as part of first-line modality therapy for glioblastoma was feasible and efficacious (NCT00805961) [74], further studies are still need. As combined inhibition of Akt and mTOR by perfosine and temsirolimus inhibited murine glioblastoma growth no matter PTEN status, a phase I/II trial in recurrent high-grade gliomais ongoing (NCT01051557) [75, 76]. Metformin is a widely prescribed antidiabetic drug and many studies indicate that metformin inhibits cancer proliferation through the inhibition of mTOR [77]. The efficacy of metformin on glioblastoma was tested in clinical trial NCT01430351 and NCT02149459. In NCT02149459, metformin was combined with radiotherapy. In NCT01430351, metformin was combined with TMZ. Both of the trials are still in phase I state.geting specifically mTORC2 could thereby be a better approach, since it would directly block Akt phosphorylation without perturbing the mTORC1-dependent feedback loops [78, 79]. In contrast to mTORC1, mTORC1/2 inhibitors can restrain Akt phosphorylation at Ser473, thus also inhibit mTORC2 at the same time [63]. AZD8055 is a potent small molecular ATP-competitive inhibitor. In vivo, AZD-8055 reduced S6 and Akt phosphorylation thereby leading to the reduction of tumor growth [80]. It is implicated that AZD8055 may provide a more promising therapeutic strategy than rapamycin and analogues [81]. Currently AZD8055 has completed the phase I clinical trials (NCT01316809).

PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitor

Since mTORC1 inhibitors could induce the loss of feedback inhibition of PI3K activation, drugs targeting PI3K and mTOR kinase simultaneously thereby become a superior option [82]. Active site ATP-competitor is a class of dual PI3K-mTOR inhibitor, which structurally targets the kinase domains of both PI3K and mTOR. PI-103 was the first dual mTOR/PI3K inhibitors that inhibited mTOR in an ATP-competitive manner [83]. In vivo study showed that PI-103 led to G0-G1 cell cycle arrest thereby inhibiting the proliferation and invasion of tumor cells [84]. However, PI-103 was halted in the preclinical period due to the poor pharmacokinetic properties. NVP-BEZ235 is a promising PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitor exhibiting improved anti-tumor potential compared to rapamycin analogs [85-88]. In preclinical test, study demonstrated that NVP-BEZ235 significantly prolonged the survival of tumor bearing animals without eliciting obvious toxicity [89]. Therefore, NVP-BEZ235 has entered phase I and phase II clinical trials with everolimus in patients with malignant solid tumors (NCT01508104). Other dual PI3K and mTOR inhibitors, such as PKI-587 and XL-765, have shown favorable activity in preclinical settings. XL-765 has completed the trial in combination with radiotherapy and TMZ for GBM as well as in subjects with recurrent GBM (NCT00704080). PKI-587 and XL-765 have recently completed the phase I clinical trials for the treatment of solid tumors (NCT00940498) and recurrent GBM who are candidates for surgical resection (NCT01240460).

THE LIMITED FACTORS OF TARGETED THERAPY BASED ON PI3K SIGNALING PATHWAY

Though more and more PI3K/Akt/mTOR targeted drugs emerge, they are still undergoing preclinical or clinical trials. Targeted therapy for GBM has yet to demonstrate an appreciable clinical survival benefit. At present, here are some possible reasons for the limited therapy effect: (1) Blood Brain Barrier. It's the most likely explanation for why targeted drugs cannot reach effective concentrations (2) Heterogeneity of GBM. No doubt the outcome of drug efficacy is much influenced by the genetic background of the tumor. In malignant tumors, molecular phenotype of the same tumor in different location may totally diverse and molecular phenotype of the same tumor in different people may also vary. Thereby the sensitivity to targeted therapy may vary. (3) The activation of alternative pathways leads to immune escape. In clinical trials, only a small proportion of the clinical trials in malignant gliomas concurrently conducted pharmacokinetic studies and most of these studies collect blood samples to work out plasma clearance, rather than directly analysis of cerebrospinal fluid or drug concentration in tumor tissues. Collectively, there are all relevant restrictions to targeted therapy based on PI3K signal pathway.

Table 3. Ongoing clinical trials in brain tumors targeting mTOR.

| Drug | Targets | Combination Partner | Patient group | Phase | State | Trail ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sirolimus | mORC1 | GBM | I/II | completed | NCT00047073 | |

| vaccine therapy | NY-ESO-1 expressing solid tumors | I | ongoing | NCT01522820 | ||

| Sirolimus, Erlotinib | mTORC1 +EGFR | glioblastoma | II | completed | NCT00672243 | |

| malignant glioma | I/II | completed | NCT00509431 | |||

| Sirolimus, Vandetanib | mTORC1 +VEGF | glioblastoma | I | completed | NCT00821080 | |

| Everolimus, Temozolomide | mTORC1 | GBM | I | completed | NCT00387400 | |

| radiation | GBM | I/II | ongoing | NCT01062399 | ||

| radiation | glioblastoma | I/II | ongoing, | NCT00553150 | ||

| Everolimus, Gefitinib | mTORC1+ EGFR | progressive GBM | I/II | completed | NCT00085566 | |

| Everolimus, Gleevec, Hydroxyurea | mTORC1, PDGFR BCR-AbI | I | completed | NCT00613132 | ||

| Everolimus, Temozolomide Bevacizumab | mTORC1, VEGF | radiation | GBM | II | completed | NCT00805961 |

| Everolimus, AEE788 | mTORC1, EGFR, VEGFR | GBM | I/II | completed | NCT00107237 | |

| Everolimus, BEZ235 | mTOR, PI3K/mTOR | Cancer | I/II | unknown | NCT01508104 | |

| Everolimus, Sorafenib | mTORC1, RAF | recurrent high-grade gliomas | I/II | recruiting | NCT01434602 | |

| Temsirolimus | mTORC1 | brain and central nervous system tumors | I | completed | NCT00784914 | |

| brain and central nervous system tumors | I/II | completed | NCT00022724 | |||

| GBM | II | completed | NCT00016328 | |||

| Temsirolimus, Doxorubicin | mTORC1 | resistant solid malignancies | I | completed | NCT00703170 | |

| Temsirolimus, Docetaxel | mTORC1 | resistant solid malignancies | I | completed | NCT00703625 | |

| Temsirolimus, Temozolomide, | mTORC1 | radiation | GBM | I | completed | NCT00316849 |

| glioblastoma | II | ongoing | NCT01019434 | |||

| Temsirolimus, Sorafenib, Erlotinib, Tipifarnib | mTORC1 +EGFR | recurrent GBM or gliosarcoma | I/II | completed | NCT00335764 | |

| Temsirolimus, Erlotinib, | mTORC1 +EGFR | recurrent malignant glioma | I/II | completed | NCT00112736 | |

| Temsirolimus, Perifosine | mTORC1, +Akt | malignant gliomas | I/II | ongoing | NCT01051557 | |

| cytoreductive surgery, Immuno-suppressant | brain tumor | II | recruiting | NCT02238496 | ||

| Temsirolimus, Bevacizumab | mTORC1 +VEGF | GBM | II | completed | NCT00800917 | |

| Ridaforolimus | mTOR | Glioma | I | completed | NCT00087451 | |

| CC-115 | DNA-PK/mTOR | advanced solid tumor | I/II | ongoing | NCT01353625 | |

| CC-223 | dual mTOR inhibitor | surgery, supportive care | advanced solid tumor | I/II | ongoing | NCT01177397 |

| XL765, Temozolomide | dual PI3K/mTOR | radiation | GBM | I | completed | NCT00704080 |

| XL147, XL765 | PI3K, PI3K/mTOR | glioblastoma, astrocytoma, Grade IV | I | completed | NCT01240460 | |

| PKI-587 | PI3K, class IA, mTORC1/C2 | solid tumor | I | completed | NCT00940498 | |

| AZD8055 | mTOR | GBM | I | completed | NCT01316809 | |

| INK128 | mTORC1/2 | Bevacizumab | recurrent glioblastoma, advanced solid tumors | I | recruiting | NCT02142803 |

| Pembrolizumab, Pictilisib, NVP-BEZ235, Ipatasertib | PI3Kα/δ, PI3K/mTOR, Akt1/2/3 | Glioblastoma | I/II | NCT02430363 | ||

| Metformin Temozolomide | mTOR | GBM | I | ongoing | NCT01430351 | |

| Metformin | mTOR | radiation | recurrent brain tumor | I | recruiting | NCT02149459 |

Clinical data related to the EGFR was searched until Nov, 2015.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

As we have discussed here, PI3K/Akt/mTOR signal pathway after activation of EGFR is one of the most significant signal pathways in tumor cells. It has confirmed that it plays an important role in the genesis and development of glioma. At the moment, targeted therapy towards intracellular signal pathways has not achieved satisfactory result yet. A future perspective for GBM therapy is combination of multiple targets and personalized treatment. Although issues like cross-talk signal pathways or tumor heterogeneity tarnished the efficacy of therapy targeted PI3K/Akt/mTOR as we expected, we still believe that it will light up a new way in glioblastoma therapy. Recent study showed that targeting HSP90 and histone deacetylases could enhance the therapeutic effect of TMZ combined with radiotherapy [90].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China to Xiaoman Li (81300800), Liang Wang (81302192) and Cao Liu (81130042 and 31171323); Liaoning research fund for higher education to Xiaoman Li (20131141) and Liang Wang (20141029); Ph.D. Programs Foundation of Ministry of Education of China to Xiaoman Li (20132104120015).

Abbreviations

- GBM

glioblastoma multiform

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- mTOR

rapamycin-sensitive mTOR-complex

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- TMZ

temozolomide

- RTKs

receptor tyrosine kinases

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten

- pS6k

ribosomal protein S6 kinase

- eIF4E

eukaryotic initiation factor 4E

- 4EBP1

eukaryotic initiation factor binding protein 1

- PIP2

phosphatidy-linositol-3, 4-bisphosphate

- PIP3

phosphatidy linositol-3, 4, 5-bisphosphate

- BBB

blood-brain-barrier

- PDK1/2

phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1/2

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olar A, Aldape KD. Using the molecular classification of glioblastoma to inform personalized treatment. J Pathol. 2014;232:165–177. doi: 10.1002/path.4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cloughesy TF, Cavenee WK, Mischel PS. Glioblastoma: from molecular pathology to targeted treatment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Messaoudi K, Clavreul A, Lagarce F. Toward an effective strategy in glioblastoma treatment. Part II: RNA interference as a promising way to sensitize glioblastomas to temozolomide. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20:772–779. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Gorlia T, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, Ondracek A, Chen Y, Wolinsky Y, Stroup NE, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006-2010. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(Suppl 2):ii1–56. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B, Belanger K, Hau P, Brandes AA, Gijtenbeek J, Marosi C, Vecht CJ, Mokhtari K, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Neyns B, Goldbrunner R, Schlegel U, Clement PM, Grabenbauer GG, Ochsenbein AF, Simon M, Dietrich PY, Pietsch T, Hicking C, Tonn JC, Diserens AC, Pica A, Hermisson M, et al. Phase I/IIa study of cilengitide and temozolomide with concomitant radiotherapy followed by cilengitide and temozolomide maintenance therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2712–2718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Network TC. Corrigendum: Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2013;494:506. doi: 10.1038/nature11903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas DA, Zhong H, Ro JY, Oddoux C, Berger AD, Pincus MR, Satagopan JM, Gerald WL, Scher HI, Lee P, Osman I. Novel mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor in localized prostate cancer. Front Biosci. 2006;11:2518–2525. doi: 10.2741/1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, Yan H, Gazdar A, Powell SM, Riggins GJ, Willson JK, Markowitz S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, Mankoo P, Carter H, Siu IM, Gallia GL, Olivi A, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Keir S, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samuels Y, Diaz LA, Jr, Schmidt-Kittler O, Cummins JM, Delong L, Cheong I, Rago C, Huso DL, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:561–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakravarti A, Zhai G, Suzuki Y, Sarkesh S, Black PM, Muzikansky A, Loeffler JS. The prognostic significance of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway activation in human gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1926–1933. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu P, Cheng H, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:627–644. doi: 10.1038/nrd2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Courtney KD, Corcoran RB, Engelman JA. The PI3K pathway as drug target in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1075–1083. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engelman JA. Targeting PI3K signalling in cancer: opportunities, challenges and limitations. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:550–562. doi: 10.1038/nrc2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burris HA., 3rd Overcoming acquired resistance to anticancer therapy: focus on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:829–842. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:492–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sami A, Karsy M. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in glioblastoma: novel therapeutic agents and advances in understanding. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:1991–2002. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0800-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellinghoff IK, Wang MY, Vivanco I, Haas-Kogan DA, Zhu S, Dia EQ, Lu KV, Yoshimoto K, Huang JH, Chute DJ, Riggs BL, Horvath S, Liau LM, Cavenee WK, Rao PN, Beroukhim R, et al. Molecular determinants of the response of glioblastomas to EGFR kinase inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2012–2024. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakravarti A, Dicker A, Mehta M. The contribution of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway to radioresistance in human gliomas: a review of preclinical and correlative clinical data. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:927–931. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, Berezov A, Wang Q, Zhang G, Drebin J, Murali R, Greene MI. ErbB receptors: from oncogenes to targeted cancer therapies. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:2051–2058. doi: 10.1172/JCI32278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang PH, Xu AM, White FM. Oncogenic EGFR signaling networks in glioma. Sci Signal. 2009;2:re6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.287re6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riehle RD, Cornea S, Degterev A. Role of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in cell signaling. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;991:105–139. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6331-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith JS, Tachibana I, Passe SM, Huntley BK, Borell TJ, Iturria N, O'Fallon JR, Schaefer PL, Scheithauer BW, James CD, Buckner JC, Jenkins RB. PTEN mutation, EGFR amplification, and outcome in patients with anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma multiforme. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1246–1256. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.16.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hay N. Interplay between FOXO, TOR, and Akt. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1965–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. An expanding role for mTOR in cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jhanwar U. Involvement of mTORC1 and mTORC2 in regulation of glioblastoma multiforme growth and motility. International Journal of Oncology. 2009;35:731–40. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu SH, Bi JF, Cloughesy T, Cavenee WK, Mischel PS. Emerging function of mTORC2 as a core regulator in glioblastoma: metabolic reprogramming and drug resistance. Cancer Biol Med. 2014;11:255–263. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dowling RJ, Topisirovic I, Fonseca BD, Sonenberg N. Dissecting the role of mTOR: lessons from mTOR inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan Q-W, Weiss WA. Inhibition of PI3K-Akt-mTOR Signaling in Glioblastoma by mTORC1/2 Inhibitors. 2012;821:349–359. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-430-8_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishikawa R, Ji XD, Harmon RC, Lazar CS, Gill GN, Cavenee WK, Huang HJ. A mutant epidermal growth factor receptor common in human glioma confers enhanced tumorigenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7727–7731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szerlip NJ, Pedraza A, Chakravarty D, Azim M, McGuire J, Fang Y, Ozawa T, Holland EC, Huse JT, Jhanwar S, Leversha MA, Mikkelsen T, Brennan CW. Intratumoral heterogeneity of receptor tyrosine kinases EGFR and PDGFRA amplification in glioblastoma defines subpopulations with distinct growth factor response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:3041–3046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114033109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Bady P, Kamoshima Y, Kouwenhoven MC, Delorenzi M, Lambiv WL, Hamou MF, Matter MS, Koch A, Heppner FL, Yonekawa Y, Merlo A, Frei K, Mariani L, Hofer S. Pathway analysis of glioblastoma tissue after preoperative treatment with the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib—a phase II trial. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1102–1112. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van den Bent MJ, Brandes AA, Rampling R, Kouwenhoven MC, Kros JM, Carpentier AF, Clement PM, Frenay M, Campone M, Baurain JF, Armand JP, Taphoorn MJ, Tosoni A, Kletzl H, Klughammer B, Lacombe D, et al. Randomized phase II trial of erlotinib versus temozolomide or carmustine in recurrent glioblastoma: EORTC brain tumor group study 26034. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1268–1274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown PD, Krishnan S, Sarkaria JN, Wu W, Jaeckle KA, Uhm JH, Geoffroy FJ, Arusell R, Kitange G, Jenkins RB, Kugler JW, Morton RF, Rowland KM, Jr, Mischel P, Yong WH, Scheithauer BW, et al. Phase I/II trial of erlotinib and temozolomide with radiation therapy in the treatment of newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme: North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study N0177. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5603–5609. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peereboom DM, Shepard DR, Ahluwalia MS, Brewer CJ, Agarwal N, Stevens GH, Suh JH, Toms SA, Vogelbaum MA, Weil RJ, Elson P, Barnett GH. Phase II trial of erlotinib with temozolomide and radiation in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2010;98:93–99. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sathornsumetee S, Desjardins A, Vredenburgh JJ, McLendon RE, Marcello J, Herndon JE, Mathe A, Hamilton M, Rich JN, Norfleet JA, Gururangan S, Friedman HS, Reardon DA. Phase II trial of bevacizumab and erlotinib in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:1300–1310. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westhoff MA, Karpel-Massler G, Bruhl O, Enzenmuller S, La Ferla-Bruhl K, Siegelin MD, Nonnenmacher L, Debatin KM. A critical evaluation of PI3K inhibition in Glioblastoma and Neuroblastoma therapy. Mol Cell Ther. 2014;2:32. doi: 10.1186/2052-8426-2-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powis G, Berggren M, Gallegos A, Frew T, Hill S, Kozikowski A, Bonjouklian R, Zalkow L, Abraham R, Ashendel C, et al. Advances with phospholipid signalling as a target for anticancer drug development. Acta Biochim Pol. 1995;42:395–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knight ZA, Shokat KM. Chemically targeting the PI3K family. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:245–249. doi: 10.1042/BST0350245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Powis G, Bonjouklian R, Berggren MM, Gallegos A, Abraham R, Ashendel C, Zalkow L, Matter WF, Dodge J, Grindey G, et al. Wortmannin, a potent and selective inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2419–2423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hartmann W, Digon-Sontgerath B, Koch A, Waha A, Endl E, Dani I, Denkhaus D, Goodyer CG, Sorensen N, Wiestler OD, Pietsch T. Phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/AKT signaling is activated in medulloblastoma cell proliferation and is associated with reduced expression of PTEN. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3019–3027. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guerreiro AS, Fattet S, Fischer B, Shalaby T, Jackson SP, Schoenwaelder SM, Grotzer MA, Delattre O, Arcaro A. Targeting the PI3K p110alpha isoform inhibits medulloblastoma proliferation, chemoresistance, and migration. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6761–6769. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bendell JC, Rodon J, Burris HA, de Jonge M, Verweij J, Birle D, Demanse D, De Buck SS, Ru QC, Peters M, Goldbrunner M, Baselga J. Phase I, dose-escalation study of BKM120, an oral pan-Class I PI3K inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:282–290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koul D, Fu J, Shen R, LaFortune TA, Wang S, Tiao N, Kim YW, Liu JL, Ramnarian D, Yuan Y, Garcia-Echevrria C, Maira SM, Yung WK. Antitumor activity of NVP-BKM120—a selective pan class I PI3 kinase inhibitor showed differential forms of cell death based on p53 status of glioma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:184–195. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wen PY, Lee EQ, Reardon DA, Ligon KL, Alfred Yung WK. Current clinical development of PI3K pathway inhibitors in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:819–829. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang TT, Sarkaria SM, Cloughesy TF, Mischel PS. Targeted therapy for malignant glioma patients: lessons learned and the road ahead. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:500–512. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ihle NT, Williams R, Chow S, Chew W, Berggren MI, Paine-Murrieta G, Minion DJ, Halter RJ, Wipf P, Abraham R, Kirkpatrick L, Powis G. Molecular pharmacology and antitumor activity of PX-866, a novel inhibitor of phosphoinositide-3-kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:763–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koul D, Shen R, Kim YW, Kondo Y, Lu Y, Bankson J, Ronen SM, Kirkpatrick DL, Powis G, Yung WK. Cellular and in vivo activity of a novel PI3K inhibitor, PX-866, against human glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:559–569. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pitz MW, Eisenhauer EA, MacNeil MV, Thiessen B, Easaw JC, Macdonald DR, Eisenstat DD, Kakumanu AS, Salim M, Chalchal H, Squire J, Tsao MS, Kamel-Reid S, Banerji S, Tu D, Powers J, et al. Phase II study of PX-866 in recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:1270–1274. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robinson JP, Vanbrocklin MW, McKinney AJ, Gach HM, Holmen SL. Akt signaling is required for glioblastoma maintenance in vivo. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:155–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bader AG, Kang S, Vogt PK. Cancer-specific mutations in PIK3CA are oncogenic in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1475–1479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510857103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Momota H, Nerio E, Holland EC. Perifosine Inhibits Multiple Signaling Pathways in Glial Progenitors and Cooperates With Temozolomide to Arrest Cell Proliferation in Gliomas In vivo. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7429–7435. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yap TA, Garrett MD, Walton MI, Raynaud F, de Bono JS, Workman P. Targeting the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway: progress, pitfalls, and promises. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:393–412. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ghobrial IM, Roccaro A, Hong F, Weller E, Rubin N, Leduc R, Rourke M, Chuma S, Sacco A, Jia X, Azab F, Azab AK, Rodig S, Warren D, Harris B, Varticovski L, et al. Clinical and translational studies of a phase II trial of the novel oral Akt inhibitor perifosine in relapsed or relapsed/refractory Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1033–1041. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao Q, Lei T, Ye F. Therapeutic targeting of EGFR-activated metabolic pathways in glioblastoma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22:1023–1040. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.806484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joy AM, Beaudry CE, Tran NL, Ponce FA, Holz DR, Demuth T, Berens ME. Migrating glioma cells activate the PI3-K pathway and display decreased susceptibility to apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4409–4417. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang G, Kang C, Pu P. Increased expression of Akt2 and activity of PI3K and cell proliferation with the ascending of tumor grade of human gliomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112:324–327. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Markman B, Dienstmann R, Tabernero J. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway—beyond rapalogs. Oncotarget. 2010;1:530–543. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cloughesy TF, Yoshimoto K, Nghiemphu P, Brown K, Dang J, Zhu S, Hsueh T, Chen Y, Wang W, Youngkin D, Liau L, Martin N, Becker D, Bergsneider M, Lai A, Green R, et al. Antitumor activity of rapamycin in a Phase I trial for patients with recurrent PTEN-deficient glioblastoma. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Knobbe CB, Trampe-Kieslich A, Reifenberger G. Genetic alteration and expression of the phosphoinositol-3-kinase/Akt pathway genes PIK3CA and PIKE in human glioblastomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2005;31:486–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2005.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu X, Hu Y, Hao C, Rempel SA, Ye K. PIKE-A is a proto-oncogene promoting cell growth, transformation and invasion. Oncogene. 2007;26:4918–4927. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mayo LD, Dixon JE, Durden DL, Tonks NK, Donner DB. PTEN protects p53 from Mdm2 and sensitizes cancer cells to chemotherapy. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5484–5489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108302200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tian XX, Zhang YG, Du J, Fang WG, Ng HK, Zheng J. Effects of cotransfection of antisense-EGFR and wild-type PTEN cDNA on human glioblastoma cells. Neuropathology. 2006;26:178–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2006.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chang SM, Wen P, Cloughesy T, Greenberg H, Schiff D, Conrad C, Fink K, Robins HI, De Angelis L, Raizer J, Hess K, Aldape K, Lamborn KR, Kuhn J, Dancey J, Prados MD. Phase II study of CCI-779 in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:357–361. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-1444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wen PY, Chang SM, Lamborn KR, Kuhn JG, Norden AD, Cloughesy TF, Robins HI, Lieberman FS, Gilbert MR, Mehta MP, Drappatz J, Groves MD, Santagata S, Ligon AH, Yung WK, Wright JJ, et al. Phase I/II study of erlotinib and temsirolimus for patients with recurrent malignant gliomas: North American Brain Tumor Consortium trial 04-02. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:567–578. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reardon DA, Desjardins A, Vredenburgh JJ, Gururangan S, Friedman AH, Herndon JE, 2nd, Marcello J, Norfleet JA, McLendon RE, Sampson JH, Friedman HS. Phase 2 trial of erlotinib plus sirolimus in adults with recurrent glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2010;96:219–230. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9950-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hainsworth JD, Shih KC, Shepard GC, Tillinghast GW, Brinker BT, Spigel DR. Phase II study of concurrent radiation therapy, temozolomide, and bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab/everolimus as first-line treatment for patients with glioblastoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2012;10:240–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao L, Vogt PK. Helical domain and kinase domain mutations in p110alpha of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase induce gain of function by different mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2652–2657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712169105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carson JD, Van Aller G, Lehr R, Sinnamon RH, Kirkpatrick RB, Auger KR, Dhanak D, Copeland RA, Gontarek RR, Tummino PJ, Luo L. Effects of oncogenic p110alpha subunit mutations on the lipid kinase activity of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem J. 2008;409:519–524. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ben Sahra I, Regazzetti C, Robert G, Laurent K, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Auberger P, Tanti JF, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Bost F. Metformin, independent of AMPK, induces mTOR inhibition and cell-cycle arrest through REDD1. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4366–4372. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Masui K, Cavenee WK, Mischel PS. mTORC2 in the center of cancer metabolic reprogramming. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Gillick JL, Neil J, Tobias M, Thwing ZE, Murali R. Distinct signaling mechanisms of mTORC1 and mTORC2 in glioblastoma multiforme: a tale of two complexes. Adv Biol Regul. 2015;57:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chresta CM, Davies BR, Hickson I, Harding T, Cosulich S, Critchlow SE, Vincent JP, Ellston R, Jones D, Sini P, James D, Howard Z, Dudley P, Hughes G, Smith L, Maguire S, et al. AZD8055 Is a Potent, Selective, and Orally Bioavailable ATP-Competitive Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Kinase Inhibitor with In vitro and In vivo Antitumor Activity. Cancer Res. 2009;70:288–298. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marshall G, Howard Z, Dry J, Fenton S, Heathcote D, Gray N, Keen H, Logie A, Holt S, Smith P, Guichard Sylvie M. Benefits of mTOR kinase targeting in oncology: pre-clinical evidence with AZD8055. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2011;39:456–459. doi: 10.1042/BST0390456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Luchman HA, Stechishin OD, Nguyen SA, Lun XQ, Cairncross JG, Weiss S. Dual mTORC1/2 blockade inhibits glioblastoma brain tumor initiating cells in vitro and in vivo and synergizes with temozolomide to increase orthotopic xenograft survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5756–5767. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fan QW, Knight ZA, Goldenberg DD, Yu W, Mostov KE, Stokoe D, Shokat KM, Weiss WA. A dual PI3 kinase/mTOR inhibitor reveals emergent efficacy in glioma. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bagci-Onder T, Wakimoto H, Anderegg M, Cameron C, Shah K. A Dual PI3K/mTOR Inhibitor, PI-103, Cooperates with Stem Cell-Delivered TRAIL in Experimental Glioma Models. Cancer Res. 2011;71:154–163. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haas-Kogan DA, Prados MD, Tihan T, Eberhard DA, Jelluma N, Arvold ND, Baumber R, Lamborn KR, Kapadia A, Malec M, Berger MS, Stokoe D. Epidermal growth factor receptor, protein kinase B/Akt, and glioma response to erlotinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:880–887. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Halatsch ME, Schmidt U, Behnke-Mursch J, Unterberg A, Wirtz CR. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition for the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme and other malignant brain tumours. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32:74–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stauffer F, Maira SM, Furet P, Garcia-Echeverria C. Imidazo[4,5-c]quinolines as inhibitors of the PI3K/PKB-pathway. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:1027–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maira SM, Stauffer F, Brueggen J, Furet P, Schnell C, Fritsch C, Brachmann S, Chene P, De Pover A, Schoemaker K, Fabbro D, Gabriel D, Simonen M, Murphy L, Finan P, Sellers W, et al. Identification and characterization of NVP-BEZ235, a new orally available dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1851–1863. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu TJ, Koul D, LaFortune T, Tiao N, Shen RJ, Maira SM, Garcia-Echevrria C, Yung WKA. NVP-BEZ235, a novel dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, elicits multifaceted antitumor activities in human gliomas. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2204–2210. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Choi EJ, Cho BJ, Lee DJ, Hwang YH, Chun SH, Kim HH, Kim IA. Enhanced cytotoxic effect of radiation and temozolomide in malignant glioma cells: targeting PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling, HSP90 and histone deacetylases. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]