Abstract

Population-based studies on Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization are scarce. We examined the prevalence, resistance, and molecular diversity of S. aureus in the general population in Northeast Germany. Nasal swabs were obtained from 3,891 adults in the large-scale population-based Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP-TREND). Isolates were characterized using spa genotyping, as well as antibiotic resistance and virulence gene profiling. We observed an S. aureus prevalence of 27.2%. Nasal S. aureus carriage was associated with male sex and inversely correlated with age. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) accounted for 0.95% of the colonizing S. aureus strains. MRSA carriage was associated with frequent visits to hospitals, nursing homes, or retirement homes within the previous 24 months. All MRSA strains were resistant to multiple antibiotics. Most MRSA isolates belonged to the pandemic European hospital-acquired MRSA sequence type 22 (HA-MRSA-ST22) lineage. We also detected one livestock-associated MRSA ST398 (LA-MRSA-ST398) isolate, as well as six livestock-associated methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (LA-MSSA) isolates (clonal complex 1 [CC1], CC97, and CC398). spa typing revealed a diverse but also highly clonal S. aureus population structure. We identified a total of 357 spa types, which were grouped into 30 CCs or sequence types. The major seven CCs (CC30, CC45, CC15, CC8, CC7, CC22, and CC25) included 75% of all isolates. Virulence gene patterns were strongly linked to the clonal background. In conclusion, MSSA and MRSA prevalences and the molecular diversity of S. aureus in Northeast Germany are consistent with those of other European countries. The detection of HA-MRSA and LA-MRSA within the general population indicates possible transmission from hospitals and livestock, respectively, and should be closely monitored.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is a common human pathogen that is able to elicit a wide range of infections, including skin and soft tissue infections, toxin-mediated diseases, and pneumonia (1–3). At the same time, around 20% of the population carries S. aureus as a persistent commensal in the nasal cavity, with the remainder being intermittently colonized (4, 5). Colonization predisposes for lymphatic and hematogenous spread and subsequent endogenous infection with the colonizing strain (6).

S. aureus exhibits increasing virulence and resistance to various antibiotics, complicating prevention and treatment of infections (2, 3). As a result, the pathogen has become one of the most common infections acquired in hospitals and the community and one of the most difficult to control (2, 7). In Germany, S. aureus is the second most common cause of hospital-acquired infections (8); 16.7% of these nosocomial infections are caused by hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (HA-MRSA) strains. Community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) strains, which represent a major threat to human health in the United States, are still rare in Germany and Europe (8, 9). However, the recent spillover of so-called livestock-associated MRSA (LA-MRSA) from livestock to humans in areas with intensive farming gives rise to concern. Worryingly, no new classes of antibiotics have been developed over the last 30 years (7). This stresses the need for a detailed knowledge of the pathogens' molecular and epidemiological characteristics as a basis for the development of effective measures for the prevention and cure of S. aureus infections.

The human S. aureus population has a highly clonal structure dominated by a dozen clonal clusters (CCs) (10). The pathogen's genome consists of a core genome (ca. 75%), a core variable genome (ca. 10%), and mobile genetic elements (MGEs) (ca. 15%) (11). The core genome is highly conserved across S. aureus strains and comprises genes associated with central metabolism and other housekeeping functions. The core variable genome is strictly linked to particular clonal lineages and includes regulators of virulence gene expression, e.g., the accessory gene regulator (agr), and surface proteins (11).

Patterns of MGEs (e.g., plasmids, phages, and pathogenicity and genomic islands) are highly varied between S. aureus isolates but nevertheless are often associated with particular clonal lineages (11, 12). MGEs carry a variety of resistance and virulence genes, encoding, for example, superantigens (SAgs), exfoliative toxins, and pore-forming toxins.

Despite the high genetic variability, all S. aureus genotypes that efficiently colonize humans are able to induce lethal infections (13). Yet, some clonal lineages, including the community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) clone USA300, appear to be more virulent than others, which may be attributed to newly acquired virulence and fitness genes, altered expression of common virulence determinants, and alterations in protein sequence that increase fitness (9, 14).

While the prevalence and molecular diversity of S. aureus within hospitals are very well documented, population-based studies on S. aureus nasal colonization are scarce. Previous studies were often limited in size or focused on selected population groups (12, 15, 16). However, population data are urgently required, as S. aureus colonization is a major risk factor for subsequent invasive S. aureus infections. Moreover, the spillover of MRSA from hospitals and livestock into the community and the spread of highly virulent community-acquired MRSA warrant in-depth monitoring of S. aureus in the general population.

We here report the prevalence and population structure of S. aureus in the general population in Western Pomerania, Germany, sampled in a large-scale comprehensive population-based study of almost 4,000 subjects, the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP-TREND) (17). SHIP-TREND includes functional tests for several organs, blood examinations, a whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), OMICs analyses of body fluids, extensive questionnaires, as well as nose swabs (17). Nasal S. aureus isolates were characterized using spa genotyping, antibiotic resistance profiling, and PCR-based virulence gene detection. Our aims were to (i) determine the prevalence of HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA in a large representative sample of the general population, (ii) identify risk factors for S. aureus and MRSA colonization, and (iii) characterize the prevalence, population structure, and molecular characteristics of S. aureus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

The Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP-TREND) is a population-based study in western Pomerania in the Northeast of Germany (17). A stratified random sample of 10,000 adults age 20 to 79 years was drawn from population registries. Sample selection was facilitated by the centralization of local population registries in the Federal State of Mecklenburg/West Pomerania. Stratification variables were age, sex, and city/county of residence. After the exclusion of migrated (n = 851) and deceased (n = 323) persons, the net sample included 8,826 persons. Because of several reasons (241 did not answer, and 3,367 refused participation), examinations were conducted in 4,420 participants between 2008 and 2012 (17).

The objective of the study is a general assessment of the population health. Hence, SHIP-TREND is not focused on single diseases or colonization with S. aureus but encompasses a wide range of health-related conditions, the collection of various common risk factors, subclinical and clinical disorders, and diseases with the widest focus possible.

A nose swab was obtained from 3,891 participants (92.2%). A subset of participants was assessed at their home using a restricted set of investigations without nose swabs (n = 409). The remainder refused the nose swabs but agreed to perform other parts of the SHIP-TREND examination.

Out of 1,052 S. aureus isolates obtained from the SHIP-TREND-0 cohort, three showed an incomplete data set lacking data on bacterial density and/or resistance. Moreover, 25 isolates were not available for genotype analyses. These 28 data sets were excluded from molecular analyses (e.g., correlation of spa type with resistance and virulence gene profiles).

Ethics statement.

The study protocol was approved on 6 March 2008 by the local ethics committee of the University of Greifswald (registration no. BB39/08), and all participants gave informed written consent.

Analysis of S. aureus nasal carriage.

Nasal samples were collected by trained examiners from both anterior nares by use of a rayon swab (BBL CultureSwab Liquid Stuart; BD, USA). Swabs were inserted into the nasal vestibule, and the swab was rotated four times. Nose swabs were stored/transported at 4°C in a transportable compressor cooler (Mobicool C40; Waeco) and processed within 12 h after sampling. SHIP examiners were trained in nose swabbing and validated on two occasions in May 2008 and October 2009. All examiners produced comparable results, as confirmed by low intra- and interobserver variability.

S. aureus identification was based on a protocol for semiquantitative S. aureus culture using a phenol red mannitol salt broth for S. aureus enrichment and mannitol salt agar (BD, Heidelberg, Germany) for quantification (see the supplemental material for details) (18). The observed colonization densities ranged from <10 CFU (category 1) to more than 3,000 CFU (category 5) obtained from 300 μl of swab transport medium. In this paper, we only report S. aureus colonization per se, while the semiquantitative data will be analyzed elsewhere. All bacterial isolates were stored at −70°C until further analysis.

S. aureus was identified by colony morphology on mannitol salt agar plates (BD, Heidelberg, Germany), coagulase test (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany), and catalase test (bioMérieux, Nürtingen, Germany). Isolates were cryoconserved using Roti-Store cryovials (Carl-Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). The identity of S. aureus was confirmed by PCR for the species-specific genes gyrase (gyr) and nuclease (nuc), as described below.

DNA isolation.

Bacterial DNA was isolated from overnight cultures according to the manufacturer's protocol for the Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

spa genotyping.

spa genotyping was performed according to published protocols using the primers spa-1113f and spa-1514r (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) (12, 19). When amplification was unsuccessful, the PCR was repeated using the alternative primers spa-239f, spa-1717r, spa-1084f, spa-1095f, spa-1618r, and spa-1517r (20, 64). The PCR products were purified (NucleoSpin gel and PCR Clean-Up kit; Macherey and Nagel, Düren, Germany) and sequenced using both amplification primers by a commercial supplier (LGC Genomics GmbH, Berlin, Germany, or GATC, Constance, Germany). The forward and reverse sequence chromatograms were analyzed with the Ridom StaphType software version 2.2.1 (Ridom GmbH, Würzburg, Germany). Closely related spa types (costs, ≤3) were grouped into spa-clonal clusters (spa CCs) using the BURP algorithm. Short spa types with fewer than five repeats were excluded from the cluster analysis (21). spa CCs were allocated to multilocus sequence type (MLST) CCs through the SpaServer database (www.spaserver.ridom.de), experimental assessment of MLST in a subset of samples (see below), and/or the scientific literature (12, 21–24). A total of 21 isolates (2.1%) could not be assigned to a CC or ST because they were classified as spa singletons (n = 8), had very short spa repeat sequences (n = 10), were spa negative (n = 1), or were untypeable due to atypical sequences flanking the spa repeat region (n = 2).

MLST.

MLST analysis was performed on a subset of 57 S. aureus isolates, as previously reported (25), and STs were identified using the MLST database http://saureus.mlst.net/. MLST was conducted to validate the classification spa type singletons and strains with short spa repeat sequences, as well as in case of a mismatch between virulence gene profiles and spa CC. Novel MLST alleles and MLST types were integrated into the MLST database (ST2796, ST2815, ST2948, ST2949, ST2964, and ST2965). The MLST ST/CC of an MLST-typed spa type was then attributed to all isolates of the same spa type and closely related spa types.

Antibiotic resistances.

Antibiotic resistances were determined using the Vitek2 system with AST-P608 and AST-P632 cards (bioMérieux, Nürtingen, Germany). The test comprised antibiotics of all major antibiotic classes, including several antibiotics of last resort: aminoglycoside antibiotics (gentamicin and tobramycin), β-lactam antibiotics (penicillin, cefoxitin, and oxacillin), 4-chinolone/fluorchinolone antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin), glycopeptide antibiotics (teicoplanin and vancomycin), lincosamide antibiotics (clindamycin and inducible clindamycin resistance), and others (tetracycline, erythromycin, fosfomycin, fusidic acid, linezolid, mupirocin, nitrofurantoin, rifampin, and tigecycline). Strains were categorized as susceptible (S), intermediate (I), or resistant (R) based on MICs; EUCAST cutoffs were used as resistance breakpoints and were set according to CLSI guidelines (http://www.clsi.org) using the Vitek2 software.

Multiplex PCR for detection of virulence and resistance genes.

PCR was used to screen for a total of 25 virulence genes. Multiplex PCRs were applied for the detection of genes for staphylococcal enterotoxins (sea to selu), toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (tst), exfoliative toxins (eta and etd), and agr groups 1 to 4, as previously reported (12, 23).

Two additional multiplex PCRs (CA-MRSA I and II) were established based on published PCR protocols to characterize community-acquired MRSA strains, i.e., the North American USA300 (ST8) and USA400 (ST1), as well as the European ST80-CA-MRSA (26–28). CA-MRSA I included 16S rRNA (controls for DNA quality), luk-PV, MW756 (targeting the genomic island vSA3 in USA400), gyrase (gyr), and methicillin resistance (mecA); CA-MRSA II included exfoliative toxin d (etd, a marker for European ST80-CA-MRSA), ACME cassette (arcA, USA300 marker), seh (USA400 marker), thermostable nuclease (nuc, S. aureus marker), and MW1409 (a Sa2int phage marker targeting USA400). For an overview on the primers, see Table S1 in the supplemental material. All assays were validated using sequenced or well-characterized bacterial control strains, including S. aureus 8325-4 and Escherichia coli (negative control), S. aureus CMRSA80 (06-00300; lukPV etd mecA), S. aureus CMRSA8 (06-01172; lukPV arcA mecA), and S. aureus CMSSA1 (05-01290; lukPV seh). The positive-control strains were kindly provided by the Robert Koch Institute, Wernigerode, Germany. The multiplex PCRs were performed with the GoTaq Flexi DNA polymerase (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). Each reaction mixture (25 μl) contained 5 μl of 5× GoTaq reaction buffer, 2.5 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (1 mM; dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), 5 μl of MgCl2 (25 mM), 0.2 μl of polymerase, and 1 μl of template DNA (10 to 20 μg/ml). In addition, CA-MRSA I contained 3.3 μl of water (distilled water DNase/RNase free; Gibco/Invitrogen) and the following primers (all 5 μM): 16S rRNA, 0.5 μl; mecA, 1 μl; gyr, 1 μl; MW756, 0.75 μl; and luk-PV, 0.75 μl. CA-MRSA II contained 0.3 μl of distilled water and the following primers: MW1409, 0.75 μl; seh, 2 μl; arcA, 0.75 μl; etd, 1 μl; and nuc, 1 μl. An initial denaturation of DNA at 95°C for 5 min was followed by 30 cycles of amplification (95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s), ending with a final extension phase at 72°C for 7 min (afterwards, storage at 4°C). All PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels (1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer; 10 μl per sample), stained with RedSafe nucleic acid staining solution (INtRON Biotechnology, South Korea), and visualized under UV light.

Strains identified as MRSA in the antibiotic resistance assay that were mecA negative (n = 3) were tested using the recently described alternative mecA and mecC primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) (29). These singleplex PCR mixtures (25 μl) contained 5 μl of 5× GoTaq reaction buffer, 2.5 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (1 mM), 5 μl of MgCl2 (25 mM), 9.3 μl of water, 1 μl of each primer (10 μM), 0.2 μl of polymerase, and 1 μl of template DNA (10 to 20 μg/ml). The cycling conditions were the same as those described above.

Rapid discrimination between the ancestral and the animal subpopulation of CC398 was performed by singleplex PCR for a recently described single nucleotide polymorphism in the SAPIG_2511 locus, according to published protocols (30). Primers hlb f5 (5′GTTGCAACACTTGCATTAGC; positions 787 to 806) and hlb r6 (5′CTTTGATTGGGTAATGAT; positions 1730 to 1712) were used for the detection of the intact hlb gene (accession no. X13404).

Minimum spanning tree.

spa types were clustered using the minimum spanning tree (MST) algorithm of the spa typing plug-in of the BioNumerics software (version 7.1; Applied Maths, Ghent, Belgium) with default settings. spa types represented by fewer than five repeats were excluded, since reliable cluster analysis of short-repeat successions seems to be limited (21).

Statistics.

For analyses, final sampling weights and the stratification variable were considered. Continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation and/or median (25% quantile, 75% quantile). Categorical data were presented as percentages. Prevalences (with standard errors [SE]) of colonization with S. aureus, MRSA, or selected CCs were determined.

To test dependencies between two categorical variables, chi-square tests were applied. The chi-square statistics were corrected for the final sampling weights and were converted into F-statistics (design-based F-test). In case of low expected numbers, an unweighted exact Fisher's test was applied. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using Stata/SE 12.0.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the SHIP-TREND-0 cohort.

The mean ± standard deviation (SD) age of study participants was 51.1 ± 15.1 years (range, 20 to 82 years). In total, 36.2% of the study participants had been exposed to a hospital environment during the last 24 months, either as a patient, a frequent visitor, or due to their profession (Table 1). In detail, 14.4% of the study participants stayed in a hospital within the previous 12 months, 21.3% frequently visited a hospital, nursing home, retirement home, or hospice during the previous 24 months, and 7% were employed in the medical sector.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the SHIP-TREND-0 participants (n = 3,891)

| Variablea | SHIP-TREND-0b |

|---|---|

| Sex of participant | |

| Female | 1,974 (50.7) |

| Male | 1,917 (49.3) |

| Age (yr) | |

| 20–29 | 356 (9.2) |

| 30–39 | 623 (16.0) |

| 40–49 | 815 (20.9) |

| 50–59 | 844 (21.7) |

| 60–69 | 744 (19.1) |

| 70–82 | 509 (13.1) |

| Hospital stay during previous 12 mo (n = 559) | 14.4 (559/3,882) |

| No. of hospitalizations (mean ± SD) | 1.4 ± 0.9 |

| No. of hospitalizations (median [25%, 75% quantiles]) | 1 (1, 1) |

| Length of stay (mean ± SD) (days) | 10.5 ± 14.5 |

| Length of stay (median [25%, 75% quantiles]) (days) | 6 (3, 11) |

| ICU stay | 12.9 (72/559) |

| ≥3 visits in hospital, nursing home, retirement home, hospice during previous 24 mo | 21.3 (826/3,882) |

| Nursing someone who visited a hospital, nursing home, retirement home, hospice during the previous 24 mo | 6.0 (231/3,882) |

| Occupation in medical sector | 7.9 (302/3,831) |

| Occupation in veterinary sector | 1.5 (56/3,831) |

| Any hospital contactc | 33.2 (1,287/3,882) |

| Any hospital contact OR occupation in medical sectorc | 36.8 (1,411/3,830) |

ICU, intensive care unit.

Data are presented as number (%) or % (number/total number), unless otherwise stated.

Any hospital contact defined as hospital stay during the previous 12 months; ≥3 visits in hospital, nursing home, retirement home, or hospice during the previous 24 months; or nursing someone who visited a hospital, nursing home, retirement home, or hospice during the previous 24 months.

Nasal carriage of MSSA and MRSA, prevalence and risk indicators.

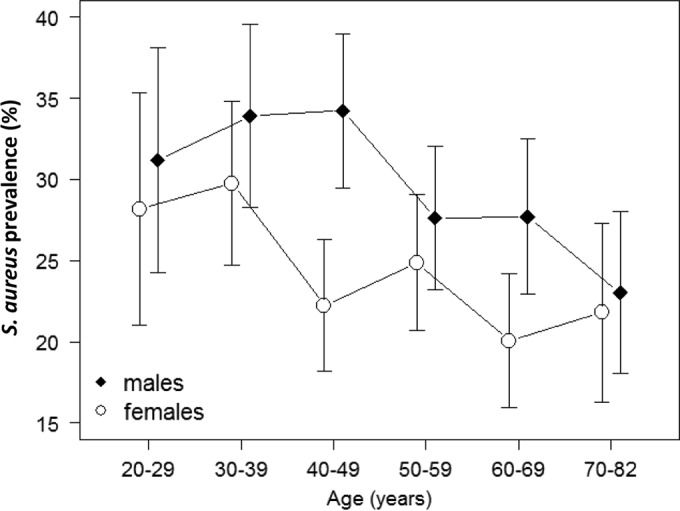

The S. aureus prevalence was 27.2%. Nasal S. aureus carriage was more preponderant in males (30.0% in males versus 24.3% in females; P < 0.001) and inversely correlated with age (P = 0.006; Table 2). If sex and age were considered simultaneously, only the age group 40 to 49 years showed a significantly elevated carriage rate in males versus females (Fig. 1). There was no association between S. aureus carriage and exposure to health care environments.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA in SHIP-TREND-0

| Variable | All S. aureus carriage |

MRSA carriage |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (SE)a | P valueb | % (SE)c | P valued | |

| Total | 27.2 (0.8) | 0.34 (0.11) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 24.3 (1.0) | 0.38 (0.16) | ||

| Male | 30.0 (1.1) | <0.001 | 0.30 (0.16) | 0.75 |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| 20–29 | 29.8 (2.5) | 0.57 (0.43) | ||

| 30–39 | 32.0 (1.9) | 0 (NA) | ||

| 40–49 | 28.6 (1.6) | 0.42 (0.24) | ||

| 50–59 | 26.3 (1.6) | 0.41 (0.24) | ||

| 60–69 | 23.8 (1.6) | 0 (NA) | ||

| 70–82 | 22.4 (1.9) | 0.006 | 0.56 (0.39) | 0.18 |

| Hospital stay during previous 12 mo | ||||

| No | 26.8 (0.8) | 0.31 (0.12) | ||

| Yes | 29.8 (2.0) | 0.17 | 0.51 (0.36) | 0.64 |

| ≥3 visits in hospital, nursing home, retirement home, hospice during previous 24 mo | ||||

| No | 27.6 (0.9) | 0.19 (0.09) | ||

| Yes | 26.0 (1.6) | 0.40 | 0.88 (0.41) | 0.042 |

| Nursing someone who visited a hospital, nursing home, retirement home, hospice during previous 24 mo | ||||

| No | 27.2 (0.8) | 0.36 (0.12) | ||

| Yes | 28.2 (3.1) | 0.74 | 0 (NA) | 1.0 |

| Occupation in medical sector | ||||

| No | 27.2 (0.8) | 0.31 (0.12) | ||

| Yes | 27.7 (2.8) | 0.83 | 0.75 (0.53) | 0.19 |

| Occupation in veterinary sector | ||||

| No | 27.2 (0.8) | 0.32 (0.11) | ||

| Yes | 25.1 (6.0) | 0.79 | 2.00 (1.98) | 0.14 |

| Any contact with health care settingse | ||||

| No | 27.0 (0.9) | 0.22 (0.10) | ||

| Yes | 27.6 (1.3) | 0.72 | 0.58 (0.27) | 0.32 |

| Any contact with health care settings OR occupation in medical sectore | ||||

| No | 27.1 (1.0) | 0.14 (0.09) | ||

| Yes | 27.4 (1.3) | 0.82 | 0.69 (0.27) | 0.045 |

Prevalence estimates were weighted, and the stratification variable was considered.

Design-based F-test. P values of <0.05 are in bold.

NA, not applicable.

Fisher's test, no weighting. P values of <0.05 are in bold.

Any contact with health care settings indicates hospital stay during the previous 12 months; ≥3 visits in hospital, nursing home, retirement home, or hospice during the previous 24 months; nursing someone who visited a hospital, nursing home, or retirement home; or hospice during the previous 24 months.

FIG 1.

Mean prevalences (error bars show 95% confidence interval) of S. aureus nasal colonization according to age and gender.

The prevalence of MRSA in the general population was low (0.34%). MRSA accounted for 0.95% (10/1,052) of the colonizing S. aureus strains. MRSA carriage was associated with frequent visits to hospitals, nursing homes, or retirement homes within the previous 24 months and with being in contact with health care settings either as a patient, visitor, or employee (Table 2). Most of the MRSA carriers (7/10) had been exposed to health care settings within the previous 24 months (Table 3). Moreover, a single person working as an animal caretaker was colonized with LA-MRSA.

TABLE 3.

Profile of MRSA-positive cases identified in the population-based study SHIP-TREND-0a

| MRSA carrier | MRSA type | Sex | Age (yr) | Hospital stay (last 12 mo) | No. of hospitalizations | Length of stay (days) | Hospitalization in ICU | ≥3 visits in hospital, nursing home, retirement home, or hospice (last 24 mo) | Nursing someone who visited a hospital, nursing home, retirement home, or hospice (last 24 mo) | Occupation | Any hospital contact or occupation in medical sector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sh19149 | HA-MRSA | Female | 28 | No | NA | NA | NA | Yes | No | Clerk | Yes |

| sh18700 | HA-MRSA | Female | 77 | Yes | 2 | 18 | No | Yes | No | Accountant | Yes |

| sh35221 | HA-MRSA | Male | 28 | No | NA | NA | NA | Yes | No | Clerk | Yes |

| sh08277 | HA-MRSA | Male | 41 | No | NA | NA | NA | No | No | Paramedic | Yes |

| sh49193 | HA-MRSA | Male | 47 | Yes | 8 | 25 | Yes | Yes | No | Road construction worker | Yes |

| sh48823 | HA-MRSA | Female | 52 | No | NA | NA | NA | Yes | No | Clerk | Yes |

| sh13413 | HA-MRSA | Female | 41 | No | NA | NA | NA | No | No | Physiotherapist | Yes |

| sh42507 | LA-MRSA | Male | 53 | No | NA | NA | NA | No | No | Animal caretaker | No |

| sh19108 | HA-MRSA | Female | 72 | No | NA | NA | NA | No | No | Retired clerk | No |

| sh12648 | HA-MRSA | Female | 56 | No | NA | NA | NA | No | No | Facility manager | No |

NA, not applicable.

Most MRSA isolates belong to the pandemic HA-MRSA-ST22 lineage.

Nine out of 10 MRSA isolates represented HA-MRSA lineages endemic to Europe. Most HA-MRSA isolates (n = 8) belonged to the pandemic European HA-MRSA-ST22 lineage (Table 4). Moreover, we detected one HA-MRSA-ST5 strain. We also isolated a single LA-MRSA strain (LA-MRSA-ST398) within the SHIP-TREND-0 cohort. Notably, we did not detect any CA-MRSA strains in our sampling cohort.

TABLE 4.

Genotype, virulence gene profile, and antibiotic resistances of MRSA isolates

| Strain ID | Genotype |

Virulence gene(s)c |

Resistance gened |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| spa type | MLSTa | Deduced MLST CCb | Endemic European MRSA lineage | agr | Non-egc SAg | egc SAg | eta, etd | luk-PV | mecA | CEF | CLI | Ind. CLI | TET | ERY | FOS | FUS | GEN | LVX | LZD | MUP | OXA | PEN | RIF | TEC | TGC | TOB | VAN | |

| sh08277 | t010 | ND | CC5 | ST5 Rhine Hesse MRSA | 2 | a, d, j, r | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − |

| sh19108 | t020 | ND | CC22 | ST22/Barnim MRSA | 1 | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| sh12648 | t020 | ND | CC22 | ST22/Barnim MRSA | 1 | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| sh48823 | t032 | ND | CC22 | ST22/Barnim MRSA | 1 | c, l | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| sh49193 | t032 | ND | CC22 | ST22/Barnim MRSA | 1 | c, l | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| sh19149 | t032 | ND | CC22 | ST22/Barnim MRSA | 1 | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| sh35221 | t032 | ND | CC22 | ST22/Barnim MRSA | 1 | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| sh13413 | t032 | ND | CC22 | ST22/Barnim MRSA | 1 | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| sh18700 | t032 | ND | CC22 | ST22/Barnim MRSA | 1 | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| sh42507 | t034 | ST398 | CC398 | ST398 LA-MRSA | 1 | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

ND, not determined.

spa types were clustered by BURP analysis into CCs, and corresponding MLST CCs were deduced using the Ridom database.

Staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) are indicated by single letters (a = sea, d = sed, j = sej, r = ser, c = sec, l = sel). agr, accessory gene regulator (1, agr1; 2, agr2); egc, superantigen genes of the enterotoxin gene cluster, i.e., seg, sei, sem, sen, seo, and seu; eta, etd, exfoliative toxins a and d, respectively; luk-PV, Panton-Valentine leukocidin gene; mecA, methicillin resistance gene.

FOX, cefoxitin; CLI, clindamycin; ind. CLI, inducible clindamycin resistance; TET, tetracycline; ERY, erythromycin; FOS, fosfomycin; FUS, fusidic acid; GEN, gentamicin; LVX, levofloxacin; LIN, linezolid; MUP, mupirocin; OXA, oxacillin; PEN, penicillin G; RIF, rifampin; TEC, teicoplanin; TGC, tigecycline; TOB, tobramycin; VAN, vancomycin.

As expected, all HA-MRSA strains were resistant to multiple antibiotics (Table 4; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). The majority of MRSA strains were resistant to levofloxacin (8/10), clindamycin (6/10), and erythromycin (6/10). Only a minority of isolates were resistant to tobramycin, tetracycline, and co-trimoxazole. No vancomycin resistance was observed. Moreover, all MRSA strains were susceptible to mupirocin, an antibiotic commonly used for sanitizing MRSA carriers (31).

In contrast, the prevalence of antibiotic resistance in MSSA strains was low. Around 62% of the MSSA strains were resistant to β-lactamase-susceptible penicillins (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Resistances to other antibiotics were rare: between 1 and 6% of MSSA strains were resistant to levofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, and tetracycline. Furthermore, we detected single strains with resistance to gentamicin, co-trimoxazole, and fusidic acid.

The S. aureus population is highly diverse.

spa typing revealed a diverse but also highly clonal S. aureus population structure. We identified a total of 357 spa types. The majority of spa types (n = 248) were represented by single isolates, illustrating the high diversity of the S. aureus population. On the other hand, the 10 most common spa types comprised more than one-third (399/1,024 isolates) of all nasal isolates: t012 (n = 63), t091 (n = 53), t084 (n = 52), t008 (n = 49), t015 (n = 47), t021 (n = 41), t005 (n = 29), t056 (n = 26), t078 (n = 23), and t346 (n = 16).

The relationship between spa types was visualized in a minimum spanning tree (Fig. 2). This graph illustrates the extremely diverse but also highly clonal S. aureus population structure. Closely related spa types were assigned to 30 CCs or sequence types (STs) (Fig. 2; see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The most common lineage was CC30, which accounted for 19.6% of the isolates, followed by CC45 (17.7%), CC15 (13.1%), CC8 (9.4%), CC22 (7.1%), CC7 (5.8%), and CC25 (5.4%). These major 7 CCs included 78.0% of all isolates. The largest CCs also showed the highest diversity of spa types, suggesting long-term diversification of these lineages (Fig. 2; see Table S3). CC7 forms an exemption, with low spa type diversity: 89.8% (53/59) isolates belong to t091, while the remaining 6 isolates belong to 5 different spa types (Fig. 1).

FIG 2.

The S. aureus population structure is highly diverse. (A) Minimum spanning tree generated from spa data using the BioNumerics software. Each sphere, or node, represents a unique spa type. The size of each node indicates the number of S. aureus isolates per spa type. The length between two nodes reflects the genetic distance between the two bordering spa types (maximum neighbor distance, 1.00). Nodes are color-coded according the presumptively associated clonal cluster. White circles represent singletons, i.e., strains that were not assigned to any CC. The identification of CCs is based on the BURP algorithm, as implemented in the Ridom StaphType software, aided by MLST sequencing of selected strains. (B) Prevalence of CCs and STs within the SHIP-TREND-0 cohort. spa types marked as excluded were not assigned to clusters, as their repeat sequence included fewer than 5 repeats, and no reliable information about phylogenetic relatedness can be inferred. spa types marked as singletons could not be assigned to a CC. CCs were color-coded in the same manner as in panel A.

Livestock-associated MRSA and MSSA have spread to the general population.

Within our sampling cohort, 2.1% of the strains belong to CCs associated with both humans and livestock, i.e., CC398 (n = 6), CC1 (n = 5), CC9 (n = 4), and CC97 (n = 6), or livestock only, i.e., CC133 (n = 1). Among these, there was a single MRSA strain in CC398. LA isolates are frequently resistant to tetracycline (Tetr) (32). Moreover, these strains typically lack the immune evasion cluster (IEC), which is located on Sa3int phages and encodes human-specific virulence factors (33). The CC398-MRSA group lacked the IEC and was Tetr, implying a recent livestock origin (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Among the CC398-MSSA isolates, only two isolates seemed to be of recent livestock origin (Tetr and either IEC negative or positive for an ORFSAPIG_2511 variant characteristic of the animal population). The other three CC398-MSSA isolates likely represented human-adapted S. aureus strains, because they were tetracycline susceptible (Tets), harbored the IEC, and lacked the respective ORFSAPIG_2511 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). Similarly, all CC9 and CC97 isolates were Tets and encoded the IEC, suggesting long-term adaptation to human hosts. All CC1 isolates were Tetr, and some lacked the IEC (n = 3). The CC133 isolate was IEC negative and Tets. To conclude, the CC133 isolate as well as a subgroup of the CC398 (n = 3) and CC1 isolates (n = 3) were probably of recent livestock origin.

agr type and virulence genes are linked to S. aureus lineages.

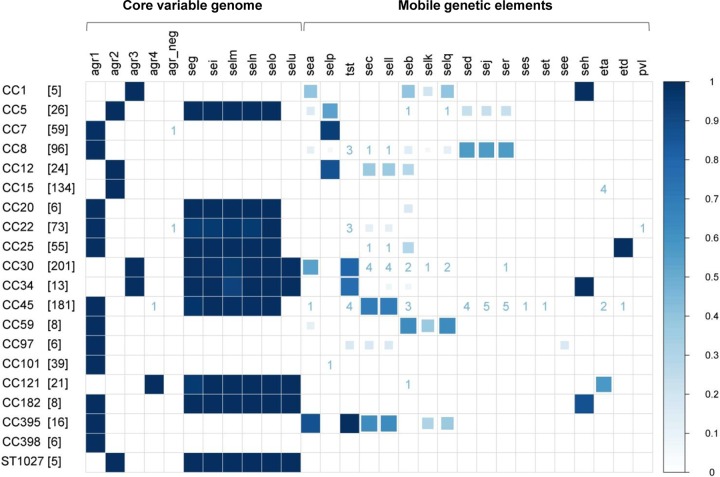

The global regulator agr (accessory gene regulator) belongs to the core variable genome and is therefore strictly linked to S. aureus lineages (11, 12). As expected, we detected agr1 in CC7, CC8, CC20, CC22, CC25, CC101, CC45, CC59, CC97, CC133, CC182, CC188, CC395, and CC398; agr2 in CC5, CC9, CC12, CC15, ST718, and ST1027; agr3 in CC1, CC30, CC34, and CC88; and agr4 in CC50 and CC121 (Fig. 3). In three cases (one isolate each from CC22 and CC45, and one isolate of spa type t779), no agr gene was amplified. A single CC45 isolate (t1081, ST45) carried agr4 instead of agr1 (an exception which has been previously reported) (34).

FIG 3.

S. aureus virulence genes are linked to CCs. Frequency plot depicting the frequency of virulence genes within each S. aureus CC, as illustrated by both color and size of the squares. If a gene occurred in fewer than 5% of isolates per CC, the number of S. aureus isolates positive for the gene is given. Virulence genes are grouped according to their genomic location. agr (agr1 to -4; agr_neg, no agr detected), and egc superantigens (seg, sei, sem, sen, seo, and seu) are core-variable genes. All other virulence genes are located on MGEs. In detail, sea and sep are encoded by the Sa3int phages, tst, sec, and sel as well as seb, sek, and seq are localized on S. aureus pathogenicity islands, while sed, sej, ser, ses, and set are carried on plasmids. eta and etd are located on a phage and plasmid, respectively, while luk-PV is located on a phage. The number of isolates per CC is provided in square brackets. CCs with more than 5 isolates are depicted.

Many virulence genes, such as exfoliative toxins, most superantigen (SAg) genes, and luk-PV, encoding the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), are located on MGEs. Others, e.g., SAg genes of the enterotoxin gene cluster (egc), are found in the core variable (CV) genome or the core genome (not in this study). As expected, the CV-carried egc SAg genes were very common (60.0% of isolates) and strictly linked to S. aureus lineages (Fig. 3; see Table S5 in the supplemental material). In contrast, virulence genes carried on MGEs were more or less tightly linked to the different CCs. For example, tst, which is found on a pathogenicity island, was predominantly found in CC30, CC34, and CC395 with single-tst-carrying strains in CC8, CC22, CC45, and CC97. Of note, the etd gene, carried on a genomic island, was restricted to CC25.

Each CC possessed a characteristic panel of MGE-encoded virulence factors, with some variations within each CC (Fig. 3) and even within individual spa types. For example, all 64 isolates of the predominant spa type t012 (CC30) carried the egc SAg genes, but only a subset contained the tst, sec, sel, seb, and/or seq carried on an S. aureus pathogenicity island (SaPI), or the phage-carried sea (Fig. 2; and data not shown). Several CCs completely lacked SAg genes: CC15, CC101, CC188, and CC398. Overall, around 22% of the S. aureus isolates were SAg negative. Notably, luk-PV was found in two MSSA isolates only: t223 (CC22) and t1445 (ST942). This toxin has been associated with severe skin and soft tissue infections, as well as severe pulmonary infections caused by both MSSA and CA-MRSA (35, 36). luk-PV-positive CC22-MSSA isolates were frequently isolated from furunculosis patients in the Szczecin area, which is close to the SHIP study region (36).

We also analyzed whether antibiotic resistances are linked to the genotype. Ampicillin resistance seemed to be lineage associated, as it was generally highly prevalent but rarely occurred in the lineages CC12, CC50, CC97, CC101, CC395, and CC398 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Moreover, the LA-MSSA lineage CC398 showed a multiresistant phenotype despite being mecA negative.

spa typing can misclassify S. aureus isolates with mosaic genomes.

spa and MLST are generally highly concordant. However, within this large study cohort, we observed some discrepancies which have been attributed to recombination events involving the spa locus (37). For example, CC34 isolates have a mosaic genome with contributions from ST30 and ST10/ST145 (including the spa locus) (38). In line with this, MLST, CV, and MGE patterns confirmed a close relationship of CC34 with CC30, while the recombined spa genes (t136, t153, t166, and t11011) are characteristic of the ST10 lineage (see Table S6 in the supplemental material). One out of the four t166 isolates and one t352 isolate, however, harbored an unusual CV pattern (agr2 instead of agr3). MLST revealed an ST10 instead of ST34. Thus, both strains likely represent an ancestral ST10 strain without mosaic genome and were hence allocated to CC10 (37, 38).

On the other hand, spa types t037 and t710 are generally assigned to ST239, a mosaic strain that has descended from ST8 and ST30 parents but has a spa type typical for ST30 strains (http://www.spaserver.ridom.de) (38). The spa type t037 and t710 isolates in this study, however, clearly belonged to CC30, based on their CV and MGE gene patterns (see Table S6 in the supplemental material) (12, 22). Both examples illustrate that the allocation of spa types to MLSTs without an assessment of characteristic CV or MGE genes can be misleading.

Another peculiarity is spa type t605, which consists of two spa repeats only (r07-r23). MLST revealed that these isolates belonged to either MLST7 or MLST15, which was also reflected by the typical SAg gene patterns. This suggests at least two different origins of t605 isolates.

spa types are not associated with sex and age of carriers.

S. aureus spa types have been previously associated with sex (t012, t021, t065, and t084) and age (t012) (39). Hence, we tested whether the six most common spa types, t012, t091, t084, t008, t015, and t021, were linked to sex or age in our large study cohort. In contrast to the previous report, we did not observe an association of common spa types with sex and age (see Table S7 in the supplemental material). Since CV and MGE gene patterns are linked to CCs, we subsequently correlated the most prevalent CCs (>5%, i.e., CC30, CC45, CC15, CC8, CC22, CC7, and CC25) with both factors. The only lineage that showed a moderate association with age was CC8 (major spa type t008), gradually declining from 14.6% in age group 20 to 29 years to 5.6% in age group 70 to 82 years (P = 0.03) (Table 5). We did not observe an association of S. aureus lineages with sex.

TABLE 5.

Distribution of the most common CCs (>5% frequency) in S. aureus carriers by sex and age (n = 1,013)a

| Variable | CC7 |

CC8 |

CC15 |

CC22 |

CC25 |

CC30 |

CC45 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (SE) | P value | % (SE) | P value | % (SE) | P value | % (SE) | P value | % (SE) | P value | % (SE) | P value | % (SE) | P value | |

| Total | 6.1 (0.8) | 9.5 (1.0) | 13.3 (1.1) | 7.1 (0.8) | 5.3 (0.7) | 19.7 (1.3) | 18.0 (1.3) | |||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 7.0 (1.4) | 9.7 (1.5) | 15.0 (1.8) | 7.4 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.0) | 19.4 (2.0) | 18.9 (2.0) | |||||||

| Male | 5.3 (1.0) | 0.31 | 9.3 (1.3) | 0.86 | 11.9 (1.4) | 0.18 | 6.9 (1.1) | 0.77 | 5.6 (1.0) | 0.57 | 19.8 (1.7) | 0.87 | 17.4 (1.7) | 0.57 |

| Age (yr) | ||||||||||||||

| 20–29 | 8.2 (3.1) | 14.6 (3.6) | 11.1 (3.1) | 5.5 (2.3) | 3.2 (1.9) | 15.7 (3.9) | 23.3 (4.4) | |||||||

| 30–39 | 5.4 (1.7) | 13.1 (2.6) | 11.0 (2.4) | 7.9 (2.0) | 1.5 (0.8) | 21.7 (3.0) | 18.8 (2.9) | |||||||

| 40–49 | 6.7 (1.7) | 6.7 (1.6) | 15.7 (2.5) | 6.3 (1.6) | 6.1 (1.7) | 18.6 (2.6) | 20.0 (2.8) | |||||||

| 50–59 | 4.7 (1.5) | 9.9 (2.1) | 9.1 (1.9) | 9.9 (2.1) | 7.9 (1.9) | 22.4 (2.9) | 13.1 (2.3) | |||||||

| 60–69 | 3.7 (1.5) | 6.1 (1.8) | 20.4 (3.3) | 4.9 (1.6) | 7.1 (2.0) | 15.3 (2.8) | 17.2 (3.0) | |||||||

| 70–82 | 8.0 (2.6) | 0.58 | 5.6 (2.1) | 0.03 | 14.8 (3.9) | 0.23 | 7.2 (2.8) | 0.44 | 5.4 (2.2) | 0.22 | 24.3 (4.4) | 0.35 | 15.3 (3.6) | 0.22 |

Comprises S. aureus isolates with complete data set, excluding isolates which had very short spa repeat sequences (n = 10), were spa negative (n = 1), or were untypeable due to atypical sequences flanking the spa repeat region (n = 2). P values are from a design-based F-test. Prevalence estimates were weighted, and design-based variables were considered. P values of <0.05 are in bold.

DISCUSSION

SHIP-TREND-0 is one of the largest studies investigating the prevalence, resistance, and diversity of S. aureus in the general adult population. By combining information on spa typing, antibiotic resistance, and virulence genes, this study not only provides new insights into the population structure of S. aureus but will also serve as a reference population for future studies on clinical cohorts.

Compared to other European countries, the prevalence of S. aureus colonization in the German population (27.2%) is in the upper range. den Heijer et al. studied the prevalence of nasal S. aureus carriage in healthy patients across nine European countries and reported an overall crude prevalence of S. aureus nasal carriage of 21.6% (n = 6,956), with Hungary (12.1%) and Austria (15.7%) at the lower end and The Netherlands (26.3%) and Sweden (29%) at the upper end (40). Our reported S. aureus prevalence might underestimate the true population prevalence, because high-risk age groups (i.e., children) were excluded, and swabs from body sites other than the nose were not obtained.

We observed 0.34% MRSA prevalence in the general population in Northeast Germany. Mehraj et al. recently reported a higher MRSA prevalence (1.29% [5/389]) in a nonhospitalized population in Braunschweig, central Germany (16). Compared to other European countries, the MRSA prevalence in the Northeast German population was in the upper range. den Heijer et al. reported MRSA prevalences in the healthy community from 0.0% (Sweden) to 0.4% (Belgium) (40). High MRSA prevalences were recently reported from the United States (up to 9.2%) (41).

Our finding that nasal carriage is associated with male sex is in line with several other studies (16, 42–44). Whether this linkage is due to factors other than hormonal disposition is still unclear. We also observed that carriage decreased with advanced age, which confirms previous reports (43, 45). In contrast, we could not reproduce the previously reported association of certain spa types with age and gender (39). The long-term persistency of S. aureus carriage in a human subpopulation of ca. 20% suggests a match between certain microbial, environmental, and host factors relevant for the maintenance of colonization. Bacterial factors contributing to successful colonization might involve lineage-specific CV and MGE genes, such as adhesions and immune evasion factors. Understanding of the host genetic susceptibility to S. aureus carriage is still in its infancy. While previous studies have used a candidate gene approach (46–48), the SHIP cohort provides the unique opportunity to identify host gene polymorphisms associated with colonization using a genome-wide association approach.

Risk factors for MRSA carriage in the community are hospitalization history, antibiotic use history, clinic visit history, being a family member of hospital employees, occupational exposure to livestock, and living on a livestock farm (49, 50). In our study, carriage was associated with frequent contacts with health care settings either as a patient, visitor, or employee.

The majority of MRSA strains belonged to the pandemic European HA-MRSA-ST22 lineage (also known as Barnim epidemic strain). ST22 is currently the most common HA-MRSA group in German hospitals (49%) and is spread all over Germany (51). In line with our findings, Tavares et al. reported that the great majority of MRSA strains found in the Portuguese community belonged to clones typically found in the hospitals, in particular, the ST22 clone (52). Moreover, all five MRSA isolates from a population-based study in Braunschweig, Germany, belonged to HA-MRSA-ST22 (16).

The HA-MRSA strains in the SHIP population demonstrated a broad antibiotic resistance profile highly similar to the HA-MRSA strains reported by the German S. aureus Reference Center, with a high incidence of resistance against ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, and clindamycin (51). Notably, we did not detect mupirocin resistance among the 10 MRSA strains, compared to 7% among the HA-MRSA submitted to the German Reference Center in 2014 (53). All of the 10 isolates from our study were susceptible to glycopeptides, linezolid, and tigecycline. As expected, antibiotic resistances in MSSA strains were rare, except for resistance to β-lactamase-susceptible penicillins. Between 4 and 8% of the MSSA strains exhibited erythromycin and clindamycin resistance, possibly due to the wide use of macrolides and lincosamides in the treatment of Gram-positive infections.

We did not find any CA-MRSA strains in our study cohort, suggesting that CA-MRSA is not endemic in Germany. This is also reflected by data from the German National Reference Center for Staphylococci, which reported only 305 cases of CA-MRSA infections in 2014 (predominantly ST5, ST80, ST8, and ST30) (53). To date, epidemiological data on the prevalence of CA-MRSA colonization in the European healthy population are rare. Nevertheless, the burden of CA-MRSA disease seems to vary drastically from country to country. In the United States, community-onset staphylococcal disease is endemic and the major cause for hospital admissions (54). High rates of CA-MRSA colonization (11.4%) in people without risk factors were reported from Portugal (52). The percentage in other European countries, including Germany, Spain, Switzerland, and Norway, was between 0 and 0.4% (39, 55–57). A drawback of SHIP is that only anterior nares were sampled, neglecting other common habitats of S. aureus, such as the perineum, pharynx, or the skin, possibly resulting in an underestimation of the true prevalence of CA-MRSA (9, 40).

The most common S. aureus lineage in our study cohort was CC30 (19.5%), followed by CC45, CC15, CC8, CC22, CC7, and CC25. These patters are in good agreement with a previous study on healthy blood donors from the same region from 2005/2006 (12), suggesting a limited fluctuation of S. aureus lineages over time. Even though the geographical distribution of colonizing S. aureus strains shows some diversity (58), there is pronounced overlap in the dominant CCs. For example, the global success of CC30 is mirrored by the fact that it is the most prevalent lineage in the healthy population in several European countries and the United States, accounting for 20 to 33% of the isolates (12, 39, 56, 58, 59). CC30 is a relatively old and highly successful lineage. luk-PV-positive ST30-MSSA strains (known as phage type 80/81) caused a pandemic of S. aureus infections after the Second World War (60). In the course of time, CC30 strains have evolved into major HA- and CA-MRSA clones (9, 60). This points to the ecological success and transmissibility of this CC. Apart from CC30, the lineages CC45, CC15, and CC8 are also frequently found among the five most prevalent lineages in several European studies (39, 42, 57, 58).

Apart from being a human opportunist, S. aureus has long been associated with livestock. Despite the strong interest in LA-MRSA, one has to keep in mind that livestock-associated lineages can be both MSSA and MRSA. Within the SHIP-TREND-0 study, we detected livestock-associated MSSA isolates belonging to CC1, CC398, and CC133. The absence of the IEC and presence of tetracycline resistance suggest a recent animal origin of some of these isolates. Notably, none of the carriers had occupations in the veterinary sector or meat-processing industry.

The discovery of CC398-LA-MRSA boosted interest in livestock as a vessel for the generation of novel MRSA, because people in contact with food production animals are at high risk of colonization with these strains (61). Even though CC398 is by far the most common LA-MRSA lineage in Germany (62), we isolated only a single bona fide CC398-LA-MRSA strain (Tetr, IEC negative), which was from an animal caretaker. In contrast, ST398-LA-MRSA represented 23% of all MRSA from hospital screening samples in the Münsterland, a region close to the German-Dutch border. Even though both the Münsterland and the SHIP region western Pomerania are areas with intensive farming, the livestock density in the Münsterland far exceeds that in western Pomerania (530 pigs/km2 versus 39 pigs/km2) (63), which might explain the comparably low rate of LA-MRSA in the SHIP cohort.

Virulence gene analyses showed that each S. aureus lineage is characterized by a defined set of core variable and MGE genes. The classification of S. aureus genes into core genome, core variable genome, and MGEs by Lindsay et al. was a milestone in S. aureus molecular epidemiology (11). As expected, core variable genes, i.e., agr type and egc SAgs, were strictly linked to S. aureus CCs in the SHIP study (11, 12). Moreover, MGE-carried SAg and exfoliative toxin gene patterns typical of different S. aureus lineages were identified, although there was considerable variation in the virulence gene profiles within each S. aureus CC and even within the same spa type. Overall, the observed patterns corroborate previous reports (11, 12, 34).

In conclusion, SHIP is one of the largest studies investigating the prevalence, antibiotic resistance, and diversity of S. aureus in the general adult population. By combining information on spa typing, antibiotic resistance, and virulence gene repertoire, this study provided insights into the population structure of S. aureus. We showed that S. aureus colonization rates in Northeast Germany are similar to reports from other European countries and that MRSA colonization is still rare. The detection of HA-MRSA and LA-MRSA clones within the general population indicates possible transmission of these strains from the hospitals and livestock, respectively, to the community and warrants close monitoring. In the future, SHIP will serve as a reference population for studies on clinical cohorts. Moreover, we now have the unique possibility to address some long-standing questions in S. aureus research, such as host genetic factors contributing to colonization as well as carriage-associated morbidity and mortality.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication made use of the spa typing website (http://www.spaserver.ridom.de/) that was developed by Ridom GmbH and curated by SeqNet (http://www.SeqNet.org/).

We thank Silver A. Wolf, Stephan Michalik, Birendra Kumar Shresta, Felix Schulze, Otto Bastrup, Markus Berg, Franziska Bluhm, Nicole Ahlbrecht, Ahmad Khadour, Stefanie Förster, Daniel Mrochen, and Susanne Neumeister for technical assistance. We also thank all SHIP examiners for taking nose swabs, namely, Daniela Gätke, Arndt Küppers, Iris Polzer, Stefanie Samietz, und Mandy Steinhöfel. We thank Stefan Monecke for helpful discussions. We are grateful to Nuno Faria for his support regarding novel MLST types and to Robert Jack for helpful comments on the manuscript.

SHIP is part of the Community Medicine Research Net of the University of Greifswald, Germany, which is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grants 01ZZ9603, 01ZZ0103, and 01ZZ0403), the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, and the Social Ministry of the Federal State of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania. This work was also supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG: no. CRC-TRR34, no. GR 1912/5-1), as well as by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research via the program HICARE (no. 01KQ1001E).

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00312-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lowy FD. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med 339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.David MZ, Daum RS. 2010. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin Microbiol Rev 23:616–687. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Kraker ME, Wolkewitz M, Davey PG, Koller W, Berger J, Nagler J, Icket C, Kalenic S, Horvatic J, Seifert H, Kaasch AJ, Paniara O, Argyropoulou A, Bompola M, Smyth E, Skally M, Raglio A, Dumpis U, Kelmere AM, Borg M, Xuereb D, Ghita MC, Noble M, Kolman J, Grabljevec S, Turner D, Lansbury L, Grundmann H, BURDEN Study Group . 2011. Clinical impact of antimicrobial resistance in European hospitals: excess mortality and length of hospital stay related to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1598–1605. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01157-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wertheim HFL. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus infections: lead by the nose. Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Hague, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Belkum A, Verkaik NJ, de Vogel CP, Boelens HA, Verveer J, Nouwen JL, Verbrugh HA, Wertheim HF. 2009. Reclassification of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage types. J Infect Dis 199:1820–1826. doi: 10.1086/599119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G. 2001. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. N Engl J Med 344:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Layer F, Werner G. 2013. MRSA: Eigenschaften, Häufigkeit und Verbreitung in Deutschland—update 2011/2012. Epidemiol Bull 21:187–193. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeLeo FR, Otto M, Kreiswirth BN, Chambers HF. 2010. Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 375:1557–1568. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61999-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindsay JA, Holden MT. 2006. Understanding the rise of the superbug: investigation of the evolution and genomic variation of Staphylococcus aureus. Funct Integr Genomics 6:186–201. doi: 10.1007/s10142-005-0019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindsay JA, Moore CE, Day NP, Peacock SJ, Witney AA, Stabler RA, Husain SE, Butcher PD, Hinds J. 2006. Microarrays reveal that each of the ten dominant lineages of Staphylococcus aureus has a unique combination of surface-associated and regulatory genes. J Bacteriol 188:669–676. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.669-676.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holtfreter S, Grumann D, Schmudde M, Nguyen HT, Eichler P, Strommenger B, Kopron K, Kolata J, Giedrys-Kalemba S, Steinmetz I, Witte W, Broker BM. 2007. Clonal distribution of superantigen genes in clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J Clin Microbiol 45:2669–2680. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00204-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melles DC, Gorkink RFJ, Boelens HAM, Snijders SV, Peeters JK, Moorhouse MJ, van der Spek PJ, van Leeuwen WB, Simons G, Verbrugh HA, van Belkum A. 2004. Natural population dynamics and expansion of pathogenic clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Invest 114:1732–1740. doi: 10.1172/JCI200423083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thurlow LR, Joshi GS, Richardson AR. 2012. Virulence strategies of the dominant USA300 lineage of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 65:5–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00937.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanger P, Nurjadi D, Gaile M, Gabrysch S, Kremsner PG. 2012. Hormonal contraceptive use and persistent Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage. Clin Infect Dis 55:1625–1632. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehraj J, Akmatov MK, Strompl J, Gatzemeier A, Layer F, Werner G, Pieper DH, Medina E, Witte W, Pessler F, Krause G. 2014. Methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage in a random sample of non-hospitalized adult population in northern Germany. PLoS One 9:e107937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Völzke H, Alte D, Schmidt CO, Radke D, Lorbeer R, Friedrich N, Aumann N, Lau K, Piontek M, Born G, Havemann C, Ittermann T, Schipf S, Haring R, Baumeister SE, Wallaschofski H, Nauck M, Frick S, Arnold A, Junger M, Mayerle J, Kraft M, Lerch MM, Dorr M, Reffelmann T, Empen K, Felix SB, Obst A, Koch B, Glaser S, Ewert R, Fietze I, Penzel T, Doren M, Rathmann W, Haerting J, Hannemann M, Ropcke J, Schminke U, Jurgens C, Tost F, Rettig R, Kors JA, Ungerer S, Hegenscheid K, Kuhn JP, Kuhn J, Hosten N, Puls R, Henke J, et al. 2011. Cohort profile: the Study of Health in Pomerania. Int J Epidemiol 40:294–307. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nouwen J, Ott A, Kluytmans-Vandenbergh M, Boelens H, Hofman A, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. 2004. Predicting the Staphylococcus aureus nasal carrier state: derivation and validation of a “culture rule.” Clin Infect Dis 39:806–811. doi: 10.1086/423376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harmsen D, Claus H, Witte W, Rothganger J, Turnwald D, Vogel U. 2003. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J Clin Microbiol 41:5442–5448. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5442-5448.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shopsin B, Gomez M, Montgomery SO, Smith DH, Waddington M, Dodge DE, Bost DA, Riehman M, Naidich S, Kreiswirth BN. 1999. Evaluation of protein A gene polymorphic region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol 37:3556–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mellmann A, Weniger T, Berssenbrugge C, Rothganger J, Sammeth M, Stoye J, Harmsen D. 2007. Based Upon Repeat Pattern (BURP): an algorithm to characterize the long-term evolution of Staphylococcus aureus populations based on spa polymorphisms. BMC Microbiol 7:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strommenger B, Kettlitz C, Weniger T, Harmsen D, Friedrich AW, Witte W. 2006. Assignment of Staphylococcus isolates to groups by spa typing, SmaI macrorestriction analysis, and multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol 44:2533–2540. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00420-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grumann D, Ruotsalainen E, Kolata J, Kuusela P, Jarvinen A, Kontinen VP, Broker BM, Holtfreter S. 2011. Characterization of infecting strains and superantigen-neutralizing antibodies in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18:487–493. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00329-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellmann A, Friedrich AW, Rosenkotter N, Rothganger J, Karch H, Reintjes R, Harmsen D. 2006. Automated DNA sequence-based early warning system for the detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus outbreaks. PLoS Med 3:e33. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enright MC, Day NP, Davies CE, Peacock SJ, Spratt BG. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 38:1008–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang K, McClure JA, Elsayed S, Louie T, Conly JM. 2008. Novel multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous identification of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains USA300 and USA400 and detection of mecA and Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes, with discrimination of Staphylococcus aureus from coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol 46:1118–1122. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01309-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang K, Sparling J, Chow BL, Elsayed S, Hussain Z, Church DL, Gregson DB, Louie T, Conly JM. 2004. New quadriplex PCR assay for detection of methicillin and mupirocin resistance and simultaneous discrimination of Staphylococcus aureus from coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol 42:4947–4955. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.11.4947-4955.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strommenger B, Braulke C, Pasemann B, Schmidt C, Witte W. 2008. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of Staphylococcus aureus isolates suspected to represent community-acquired strains. J Clin Microbiol 46:582–587. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01600-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuny C, Layer F, Strommenger B, Witte W. 2011. Rare occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC130 with a novel mecA homologue in humans in Germany. PLoS One 6:e24360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuny C, Abdelbary M, Layer F, Werner G, Witte W. 2015. Prevalence of the immune evasion gene cluster in Staphylococcus aureus CC398. Vet Microbiol 177:219–223. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hetem DJ, Bonten MJ. 2013. Clinical relevance of mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect 85:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stegger M, Liu CM, Larsen J, Soldanova K, Aziz M, Contente-Cuomo T, Petersen A, Vandendriessche S, Jimenez JN, Mammina C, van Belkum A, Salmenlinna S, Laurent F, Skov RL, Larsen AR, Andersen PS, Price LB. 2013. Rapid differentiation between livestock-associated and livestock-independent Staphylococcus aureus CC398 clades. PLoS One 8:e79645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Wamel WJ, Rooijakkers SH, Ruyken M, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA. 2006. The innate immune modulators staphylococcal complement inhibitor and chemotaxis inhibitory protein of Staphylococcus aureus are located on beta-hemolysin-converting bacteriophages. J Bacteriol 188:1310–1315. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.4.1310-1315.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monecke S, Coombs G, Shore AC, Coleman DC, Akpaka P, Borg M, Chow H, Ip M, Jatzwauk L, Jonas D, Kadlec K, Kearns A, Laurent F, O'Brien FG, Pearson J, Ruppelt A, Schwarz S, Scicluna E, Slickers P, Tan HL, Weber S, Ehricht R. 2011. A field guide to pandemic, epidemic and sporadic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 6:e17936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lina G, Piemont Y, Godail-Gamot F, Bes M, Peter M, Gauduchon V, Vandenesch F, Etienne J. 1999. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 29:1128–1132. doi: 10.1086/313461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masiuk H, Kopron K, Grumann D, Goerke C, Kolata J, Jursa-Kulesza J, Giedrys-Kalemba S, Broker BM, Holtfreter S. 2010. Association of recurrent furunculosis with Panton-Valentine leukocidin and the genetic background of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 48:1527–1535. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02094-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas JC, Godfrey PA, Feldgarden M, Robinson DA. 2012. Draft genome sequences of Staphylococcus aureus sequence type 34 (ST34) and ST42 hybrids. J Bacteriol 194:2740–2741. doi: 10.1128/JB.00248-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson DA, Enright MC. 2004. Evolution of Staphylococcus aureus by large chromosomal replacements. J Bacteriol 186:1060–1064. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.1060-1064.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sangvik M, Olsen RS, Olsen K, Simonsen GS, Furberg AS, Sollid JU. 2011. Age- and gender-associated Staphylococcus aureus spa types found among nasal carriers in a general population: the Tromsø Staph and Skin Study. J Clin Microbiol 49:4213–4218. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05290-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.den Heijer CD, van Bijnen EM, Paget WJ, Pringle M, Goossens H, Bruggeman CA, Schellevis FG, Stobberingh EE, APRES Study Team . 2013. Prevalence and resistance of commensal Staphylococcus aureus, including meticillin-resistant S. aureus, in nine European countries: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis 13:409–415. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Creech CB Jr, Kernodle DS, Alsentzer A, Wilson C, Edwards KM. 2005. Increasing rates of nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 24:617–621. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000168746.62226.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skramm I, Moen AE, Bukholm G. 2011. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: frequency and molecular diversity in a randomly sampled Norwegian community population. APMIS 119:522–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorwitz RJ, Kruszon-Moran D, McAllister SK, McQuillan G, McDougal LK, Fosheim GE, Jensen BJ, Killgore G, Tenover FC, Kuehnert MJ. 2008. Changes in the prevalence of nasal colonization with Staphylococcus aureus in the United States, 2001–2004. J Infect Dis 197:1226–1234. doi: 10.1086/533494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, van Leeuwen W, van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA, Nouwen JL. 2005. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis 5:751–762. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munckhof WJ, Nimmo GR, Schooneveldt JM, Schlebusch S, Stephens AJ, Williams G, Huygens F, Giffard P. 2009. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus, including community-associated methicillin-resistant strains, in Queensland adults. Clin Microbiol Infect 15:149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emonts M, Uitterlinden AG, Nouwen JL, Kardys I, Maat MP, Melles DC, Witteman J, Jong PT, Verbrugh HA, Hofman A, Hermans PW, van Belkum A. 2008. Host polymorphisms in interleukin 4, complement factor H, and C-reactive protein associated with nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and occurrence of boils. J Infect Dis 197:1244–1253. doi: 10.1086/533501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruimy R, Angebault C, Djossou F, Dupont C, Epelboin L, Jarraud S, Lefevre LA, Bes M, Lixandru BE, Bertine M, El Miniai A, Renard M, Bettinger RM, Lescat M, Clermont O, Peroz G, Lina G, Tavakol M, Vandenesch F, van Belkum A, Rousset F, Andremont A. 2010. Are host genetics the predominant determinant of persistent nasal Staphylococcus aureus carriage in humans? J Infect Dis 202:924–934. doi: 10.1086/655901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van den Akker EL, Nouwen JL, Melles DC, van Rossum EF, Koper JW, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Verbrugh HA, Pols HA, Lamberts SW, van Belkum A. 2006. Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage is associated with glucocorticoid receptor gene polymorphisms. J Infect Dis 194:814–818. doi: 10.1086/506367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paget J, Aangenend H, Kuhn M, Hautvast J, van Oorschot D, Olde Loohuis A, van der Velden K, Friedrich AW, Voss A, Kock R. 2015. MRSA carriage in community outpatients: a cross-sectional prevalence study in a high-density livestock farming area along the Dutch-German border. PLoS One 10:e0139589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hidron AI, Kourbatova EV, Halvosa JS, Terrell BJ, McDougal LK, Tenover FC, Blumberg HM, King MD. 2005. Risk factors for colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in patients admitted to an urban hospital: emergence of community-associated MRSA nasal carriage. Clin Infect Dis 41:159–166. doi: 10.1086/430910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Layer F, Cuny C, Strommenger B, Werner G, Witte W. 2012. Aktuelle Daten und Trends zu Methicillin-resistenten Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Nationales Referenzzentrum für Staphylokokken und Enterokokken, Robert Koch-Institut, Wernigerode, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tavares A, Miragaia M, Rolo J, Coelho C, de Lencastre H, CA-MRSA/MSSA Working Group. 2013. High prevalence of hospital-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the community in Portugal: evidence for the blurring of community-hospital boundaries. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 32:1269–1283. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1872-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Werner G. 2015. MRSA: Eigenschaften, Häufigkeit und Verbreitung in Deutschland—update 2013/2014. Epidemiol Bull 31:303–309. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Carey RB, Talan DA, the EMERGEncy ID Net Study Group. 2006. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med 355:666–674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lozano C, Gomez-Sanz E, Benito D, Aspiroz C, Zarazaga M, Torres C. 2011. Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage, virulence traits, antibiotic resistance mechanisms, and genetic lineages in healthy humans in Spain, with detection of CC398 and CC97 strains. Int J Med Microbiol 301:500–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sakwinska O, Kuhn G, Balmelli C, Francioli P, Giddey M, Perreten V, Riesen A, Zysset F, Blanc DS, Moreillon P. 2009. Genetic diversity and ecological success of Staphylococcus aureus strains colonizing humans. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:175–183. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01860-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Monecke S, Luedicke C, Slickers P, Ehricht R. 2009. Molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus in asymptomatic carriers. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 28:1159–1165. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0752-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruimy R, Armand-Lefevre L, Barbier F, Ruppe E, Cocojaru R, Mesli Y, Maiga A, Benkalfat M, Benchouk S, Hassaine H, Dufourcq JB, Nareth C, Sarthou JL, Andremont A, Feil EJ. 2009. Comparisons between geographically diverse samples of carried Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 191:5577–5583. doi: 10.1128/JB.00493-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feil EJ, Cooper JE, Grundmann H, Robinson DA, Enright MC, Berendt T, Peacock SJ, Smith JM, Murphy M, Spratt BG, Moore CE, Day NPJ. 2003. How clonal is Staphylococcus aureus? J Bacteriol 185:3307–3316. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3307-3316.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robinson DA, Kearns AM, Holmes A, Morrison D, Grundmann H, Edwards G, O'Brien FG, Tenover FC, McDougal LK, Monk AB, Enright MC. 2005. Re-emergence of early pandemic Staphylococcus aureus as a community-acquired meticillin-resistant clone. Lancet 365:1256–1258. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cuny C, Wieler LH, Witte W. 2015. Livestock-associated MRSA: the impact on humans. Antibiotics 4:521–543. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics4040521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Köck R, Schaumburg F, Mellmann A, Koksal M, Jurke A, Becker K, Friedrich AW. 2013. Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) as causes of human infection and colonization in Germany. PLoS One 8:e55040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ministerium für Landwirtschaft, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. 2014. Statistisches Datenblatt. Ministerium für Landwirtschaft, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Schwerin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bartels MD, Petersen A, Worning P, Nielsen JB, Larner-Svensson H, Johansen HK, Andersen LP, Jarløv JO, Boye K, Larsen AR, Westh H. 2014. Comparing whole-genome sequencing with Sanger sequencing for spa typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 52:4305–4308. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01979-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.