Abstract

Natural products comprise valuable sources for new antiparasitic drugs. Here we tested the effects of a novel β–lapachone derivative on Trypanosoma cruzi parasite survival and proliferation and used microscopy and cytometry techniques to approach the mechanism(s) underlying parasite death. The selectivity index determination indicate that the compound trypanocidal activity was over ten-fold more cytotoxic to epimastigotes than to macrophages or splenocytes. Scanning electron microscopy analysis revealed that the R72 β–lapachone derivative affected the T. cruzi morphology and surface topography. General plasma membrane waving and blebbing particularly on the cytostome region were observed in the R72-treated parasites. Transmission electron microscopy observations confirmed the surface damage at the cytostome opening vicinity. We also observed ultrastructural evidence of the autophagic mechanism termed macroautophagy. Some of the autophagosomes involved large portions of the parasite cytoplasm and their fusion/confluence may lead to necrotic parasite death. The remarkably enhanced frequency of autophagy triggering was confirmed by quantitating monodansylcadaverine labeling. Some cells displayed evidence of chromatin pycnosis and nuclear fragmentation were detected. This latter phenomenon was also indicated by DAPI staining of R72-treated cells. The apoptotis induction was suggested to take place in circa one-third of the parasites assessed by annexin V labeling measured by flow cytometry. TUNEL staining corroborated the apoptosis induction. Propidium iodide labeling indicate that at least 10% of the R72-treated parasites suffered necrosis within 24 h. The present data indicate that the β–lapachone derivative R72 selectively triggers T. cruzi cell death, involving both apoptosis and autophagy-induced necrosis.

Keywords: Trypanosoma cruzi, Chagas disease, Chemotherapy, Natural products, β–lapachone derivative

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

β-Lapachone derivative displays antiparasitic acticity upon Trypanosoma cruzi parasites with little effects on mammalian cells.

-

•

β-Lapachone derivative trypanocidal activity involves autophagy-mediated secondary necrosis.

-

•

Semisynthetic product caused necrotic death via cumulative autophagosome fusion.

-

•

Electron microscopy helps shedding light on β-Lapachone derivative mode of action.

1. Introduction

Neglected tropical diseases cause over 100,000 deaths every year (GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (2015)) and circa 10% of that is due to Chagas disease (World Health Organization, 2016). This parasitic disease was discovered over a century ago in Brazil and presently this nation spends at least US$ 5.6 million/year for chagasic workers absenteeism and these losses reach US$ 1.2 billion/year in southern Latin American countries (World Health Organization, 2010). As effective vaccines for parasitic diseases are generally not available, chemotherapy remains of pivotal importance in the fight against such pathogens. Presently only nifurtimox and benznidazole are used in chemotherapy, (only the latter is used in Brazil) and both present important adverse effects, which may be evidenced clinically (Castro et al., 2006, Pinazo et al., 2010, Santos et al., 2012) or biochemically/ultrastructurally (De Castro et al., 2003, Bartel et al., 2007). Despite reports of successful treatment of chronic infections in both human (Moreira et al., 2013b, Aguiar et al., 2012, Viotti et al., 2011, Hasslocher-Moreno et al., 2012) and experimental models (Garcia et al., 2005) the effectiveness of chronic infection chemotherapy is considered controversial (Pinazo et al., 2010, Matta-Guedes et al., 2012). Thus, the search for new effective drugs remains required.

Medicinal plants may provide many compounds with antiparasitic properties (Tagboto and Townson, 2001, Fournet and Muñoz, 2002, Izumi et al., 2011, Wink, 2012) and nearly half of the drugs listed as basic by the WHO are either natural or based on natural compounds (Newman and Cragg, 2007). The synthetically modified natural compounds may comprise an even more diversified source of potential drugs, allowing studies of structure-activity relationship against parasitic protozoa (e.g. Bernardino et al., 2006, Salas et al., 2008, Souza-Neta et al., 2014). Natural plant-derived quinones and their derivatives may exert multifactorial effects upon distinct targets on antiparasitic chemotherapy (Pinto and Castro, 2009, Salas et al., 2008, Belorgey et al., 2013). Naphtoquinones such as β–lapachone are natural products isolated from different higher plant families and shown to present antimalarial (Carvalho et al., 1988, De Andrade-Neto et al., 2004, Pérez-Sacau et al., 2005), giardicidal (Corrêa et al., 2009), leishmanicidal (Guimarães et al., 2013) and trypanocidal activity against T. brucei (De Pahn et al., 1988) and Trypanosoma cruzi (Boveris et al., 1978, Docampo et al., 1978, Goijman and Stoppani, 1985, Pinto et al., 1997, Pinto et al., 2000, Menna-Barreto et al., 2005, Menna-Barreto et al., 2007, Menna-Barreto et al., 2009a, 2014). Furthermore, lapachone derivatives/analogues may display enhanced antiparasitic activity upon T. cruzi (Pinto et al., 1997; Ferreira et al., 2011, Diogo et al., 2013).

The detailed understanding of parasite cell biology as well as the ultrastructural alterations brought by lead compounds may furnish chemotherapy approaches with information on target organelles/pathways helping elucidating action mechanism(s) and thus enabling an effective rational drug design (e.g. Vannier-Santos and Lins, 2001, De Souza, 2002, Vannier-Santos et al., 2002, Rodrigues and de Souza, 2008, Da Silva Júnior et al., 2008, Vannier-Santos and De Castro, 2009, Menna-Barreto et al., 2009b). We have previously shown that electron microscopy approaches may shed light on the mechanism of action of antiparasitic compound(s) and natural product derivatives on T. cruzi subcellular compartments (Menezes et al., 2006, Souza-Neta et al., 2014, Sueth-Santiago et al., 2016).

Here we tested the β–lapachone derivative R72 effects upon T. cruzi epimastigotes. Fluorescence and electron microscopy were employed to approach the mechanisms underlying the parasite cell death produced by the natural product derivative.

2. Material and methods

2.1. β–lapachone derivative

The synthesis of phosphorohydrazidic acid, N'-[(6Z)-3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-5-oxo-2H-naphtho[1,2-b]pyran-6(5H)-ylidene]-bis(1-methylpropyl) ester, was performed by adding equimolar amount of phosphorohydrazidic acid, bis(1-methylpropyl) ester, and β−lapachone in ethyl alcohol, with catalytic amounts of concentrated hydrochloric acid (Fig. 1). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. At the end of reaction, in order to neutralize the reaction medium, a 10% sodium bicarbonate solution was added. The resulting solution was transferred to a separatory funnel with equal amounts of water and methylene chloride. After separation of the organic layer, anhydrous magnesium sulfate was added for complete removal of the water remaining. The solvent of the resulting filtered solution was evaporated to give a yellow oil, which was purified by column chromatography in hexane and ethyl acetate in the ratio 5:1. The yield after this purification was 66%. The β–lapachone derivative, hereon termed R72, molecular model, synthesis pathway and NMR spectrum are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Decoupled 31P Nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum of N’[(6Z)- 3,4- dihydro - 2,2- dimethyl - 5- oxo- 2H- naphthol [1,2-b] pyran - 6 (5H)- ilidene], ester di-sec-butylic phosphorohydrazidic acid (R72). The R72 synthesis of was performed by adding equimolar amounts of phosphorohydrazidic acid, bis(1-methylpropyl) ester, and β−lapachone in ethyl alcohol, with catalytic amounts of concentrated hydrochloric acid. In the detail: the molecular R72 structure.

2.2. Parasites

Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes Y-strain were cultured at 28 °C in LIT (liver infusion trypticase) medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 μg/mL penicillin and streptomycin. Cultures were inoculated with 107 cells/mL and parasites were harvested at mid-log growth phase by centrifugation at 1000g and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times before the experiments. Parasite growth was assessed by daily counting on hemocytometer chambers under phase contrast microscopy.

2.3. Trypanocidal activity

The 5 × 105 parasites inocula were incubated in the presence or absence of 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 μM R72 for 96 h. Afterwards, parasites were counted in Neubauer hemocytometer chambers under phase-contrast microscopy. The IC50 value was determined using the Graphpad Prism version 5.0 software.

2.4. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Parasites before and after incubation with 19 μM R72 for 48 h were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 2% formaldehyde and 2.5 mM CaCl2 in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.2, post-fixed in 1% OsO4, 0.8% potassium ferricyanide and 2.5 mM CaCl2 in the same buffer for 60 min. Samples were dehydrated in acetone series and embedded in Polybed resin. Thin sections obtained on diamond knives were stained with aqueous solutions of 5% uranyl acetate and 3% lead citrate for 30 min and 5 min, respectively. Samples were observed under a JEOL 1230 or Zeiss 109 transmission electron microscopes.

2.5. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

R72 treated and untreated parasites were fixed and postfixed as above, dehydrated in ethanol series, submitted to the critical point drying method in a Balzers apparatus, mounted on stubs, and metalized with a circa 20 nm-thick gold layer. Samples were observed under a JEOL 5310 scanning electron microscope.

2.6. Cytotoxicity assessment

Cells pellets of 106 Balb/c splenocytes or 105 peritoneal macrophages incubated for 24 h were solubilized in DMSO, transferred to flat-bottomed 96-well plates. Cytotoxic effects were determined as cytotoxic concentrations (CC50) using the dye MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) method, revealing activity of NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductases, by the tetrazolium reducing into insoluble formazan read spectrometrically at 540 nm in ELISA reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Treated (12–1000 μM) and untreated cells were washed, kept in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% (v/v) MTT and incubated for 16 h. MTT reduction by macrophages or splenocytes containing solely MTT and DMSO were employed as controls (Menezes et al., 2006, Vannier-Santos et al., 2008). R72 Selectivity index was determined as the ratio of CC50 on mammalian cells to IC50 on epimastigotes (CC50/IC50).

2.7. Fluorescence microscopy

Parasites before and after incubation with 19 μM R72 for 24 h were fixed in formaldehyde, washed in PBS, adhered in poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips and stained with 0.05 mM monodansylcadaverine (MDC) or 1 μg/mL 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for detections localization of autophagic and nuclear compartments, respectively. Percentage cells displaying punctate staining was determine by examination of over 500 cells per experiment. Statistical analysis was performed using chi-square with Yates correction (1 degree of freedom), with P < 0.0001 (two-tailed). Samples were analyzed in an Olympus BX51fluorescence microscope or confocal microscope Leica SP8.

2.8. Flow cytometry analysis

Epimastigotes (3 × 106 cells in 300 μL) incubated or not with 19 μM R72 for 24, 48 and 72 h were centrifuged at 1000g for 10 min and washed twice in sterile PBS. Then 5 × 105 cells/mL were incubated with 10 μg/mL annexin V-FITC and 5 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) for 24 h. Data collection and the analysis were conducted using the FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, USA). A total of at least 10,000 events were acquired on Diva software version 6.1 and the gates were previously established for T. cruzi cells. Double-negative cells were considered intact, whereas double-positive cells were considered in late apoptosis/necrotic cells. Annexin+/PI− cells are presumably in early apoptosis and the annexin−/PI+ may be considered necrotic. The cell permeant reagent 2′,7′ –dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA) was used to measure reactive oxygen species (ROS)-producing cells before and after R72 treatment.

2.9. DNA fragmentation detection using TUNEL assays

T. cruzi epimastigotes (1 × 107) were incubated with 19 μM R72 or DMSO for 24 h for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL). Cells were washed three times with sterile PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h. Then parasites were washed with PBS and permeabilized with a solution of 0.2% Triton-X in PBS for 5 min. After permeabilization, samples were washed with PBS resuspended Equilibration buffer (Promega kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Negative controls were incubated with the same solution devoid of Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase Recombinant enzyme (rTdT), whereas positive controls were incubated with 5 μg/mL DNAse for 5 min. Data acquisition was performed by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA) and at least 10,000 events were acquired.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Comparisons between groups were performed by the unpaired Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA and a posteriori Tukey's tests, by use of Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad). For all tests, differences of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

2.11. Ethical aspects

All the procedures performed were approved by the Fiocruz Ethics Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (license no. 20/2015) and rigorously followed the ethics standards guidelines of International Council for Laboratory Animal Science.

3. Results

3.1. Parasite multiplication

T. cruzi epimastigote proliferation/survival assessed 96 h after R72 β-lapachone derivative addition (Fig. 2A). The naphtoquinone significantly (p < 0.05) diminished the protozoan proliferation at 20 μM and the inhibition was highly significant (p < 0.001) at 30–50 μM, producing 19 μM IC50.

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory effect of the β-lapachone derivative R72 upon T. cruzi in vitro proliferation. Epimastigote forms were cultured in the presence of different R72 concentrations and counted under phase microscopy after 96 h. The compound significantly (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001) impaired the parasite proliferation producing a 19 μM IC50value (A). Inhibitory effect of the β-lapachone derivative R72 upon murine macrophage (B) and splenocyte (C) viability assessed by the MTT method, produced CC50 values of 243 μM and 212 μM, respectively (*p < 0.05). The selectivity indexes (CC50/IC50) determined for these cell types were 12.78 and 11.15, respectively. These data are mean of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicates. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA and Tukey post-test.

3.2. Cytotoxicity

In order to test its possible selectivity, the compound was assayed on mammalian cells. The murine splenocyte and macrophage viabilities were approached using the MTT method before and after R72 addition. We notice that the β-lapachone derivative R72 was much less toxic to murine macrophages (Fig. 2B) and splenocytes (Fig. 2C), as viability assessed by the MTT method, produced CC50 values of 243 μM and 212 μM, respectively (*p < 0.05). Therefore, the selectivity indexes obtained for these cell types were 12.78 and 11.15, respectively.

3.3. Parasite morphology and topography

SEM was employed to analyze the R72-treated parasite morphology and surface topology. Contrary to controls (Fig. 3A and B), the R72-treated parasites often displayed plasma membrane wavy patterns and blebbing was observed particularly in the cytostome area (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of untreated (A) and DMSO-treated (B) controls, where the normal cytostome opening is evident (B, arrow). R72-treated parasites displayed ruffled plasma membrane and blebbing (*) was observed particularly in the cytostome opening area (C, arrow).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to analyze the R72 effects on the parasite subcellular organization. TEM images corroborated the asymmetric alteration of the epimastigote cytostome (Fig. 4A and B). The effect appeared to be exerted on the cytostome opening membrane whereas the microtubular cytopharinx remained undamaged. R72-treated parasites also presented enlarged mitochondria with unusual kDNA arrays (Fig. 4C) and supernumerary basal bodies (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Contrary to the regular cytostomes in DMSO-treated parasites observed by TEM (A, arrow), R72-treated parasites presented debris-associated damaged cytostome opening (B, arrow), but the cytopharinx microtubules apparently remained intact (B, *). DMSO-treated parasites showed no alteration as compared to untreated cells. Some R72-treated parasites displayed large kinetoplasts (C - K) with altered kDNA compacting pattern (arrowhead) as well as supernumerary basal bodies (Fig. 4C arrowheads). Bars – 500 nm.

3.4. ROS generation

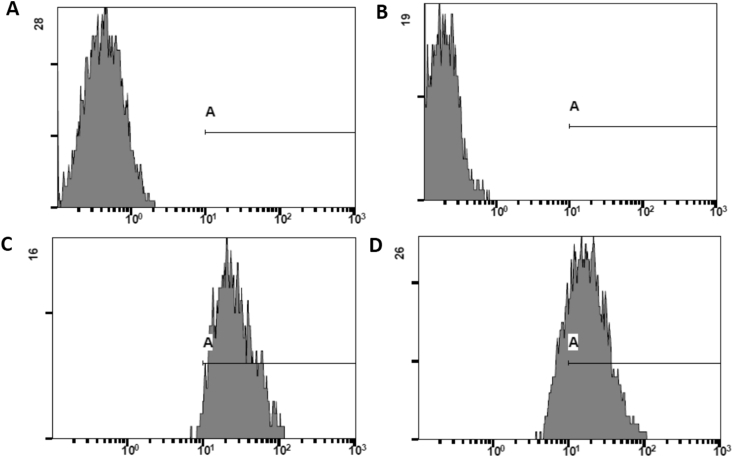

ROS production accessed by the use of the cell permeant probe DCFDA. Contrary to untreated controls (Fig. 5A), which showed no significant labeling, parasites incubated with R72 for 1 h (Fig. 5B), 3 h (Fig. 5C) and 24 h (Fig. 5D), displayed, respectively, 93.6%, 53.7% and 41.1% DCFDA-positive cells.

Fig. 5.

ROS production accessed by flow cytometry of parasites incubated with the cell permeant probe reagent 2′,7’ –dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA). Untreated parasite controls displayed circa 0.9% stained cells (A), whereas parasites incubated with 19 μM R72 for 1 h (B), 3 h (C) and 24 h (D) presented, respectively 93.6%, 53.7% and 41.1% DCFDA-positive cells.

3.5. Mechanisms of parasite cell death

Pycnotic nuclei were eventually observed in the derivative-treated parasites (Fig. 6A) and some presented nuclear envelope protrusions and structures suggesting nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 6B), what was confirmed by DAPI DNA staining (Fig. 6C and D).

Fig. 6.

R72-treated parasites eventually presented pycnotic nuclei (A - N, *) and some TEM images displayed nuclear protrusions (B arrows) and compartments of similar content suggesting budding of nuclear fragments (B, arrowhead). Fluorescence microscopy using the DNA probe DAPI revealed the normal nucleus and kinetoplast labeling of both untreated and DMSO-treated control cells (C arrows arrowheads) and showed evidence of nuclear fragmentation in some R72-treated parasites (D, arrowhead).

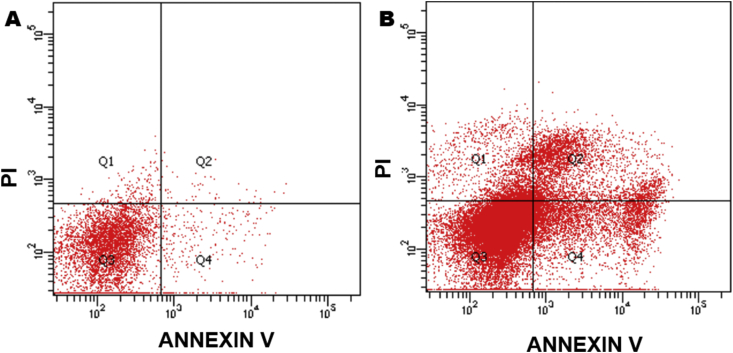

Flow cytometry analysis of T. cruzi epimastigotes was employed to verify the cell death mechanism(s) triggered by R72 (Fig. 7). Parasites were coincubated with annexin V (aV) and PI, probes to evaluate phosphatidylserine expression and membrane discontinuity, respectively. Untreated control parasites displayed 91.2% of double negative cells (Fig. 7 A), whereas cultures incubated with R72 for 24 h were 16.8% PI-negative, but annexin V-positive, indicating cells undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 7 B). The 12.2% PI-positive and aV-positive cells, presumably correspond to late apoptosis/secondary necrosis.

Fig. 7.

Cell death mechanism(s) in R72-treated parasites evaluation by flow cytometry, in cells coincubated with PI and annexin V probes. Untreated controls displayed 91.2% of double negative cells (A), whereas cultures incubated with 19 μM R72 for 24 h (B) displayed 16.8% PI-negative, but annexin V-positive, indicating cells undergoing apoptosis as well as 12.2% PI-positive and AV-positive cells, corresponding to late apoptosis/secondary necrosis. DMSO-treated controls were not labeled.

In order to test whether DNA fragmentation took place, corroborating the aV indication of apoptosis, we performed TUNEL assays. Parasites incubated with 19 μM R72 for 24 h displayed 93.3% labeled cells assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

DNA fragmentation detection employing the TUNEL method. 107T. cruzi epimastigotes incubated or not with 19 μM R72 for 24 h were analyzed by flow cytometry. Negative Control (A) assayed in the absence of rTdT (recombinant terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase) and DMSO-treated parasites (B) displayed similar patterns, with no stained cells in the gate, whereas positive control, employing DNAse (C) and R72-treated parasites (D) showed TUNEL staining on 77.6% and 93.3% cells, respectively.

The probe MDC was used to test the autophagy induction was monitored by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 9A B). Contrary to untreated or DMSO-treated controls (A), R72-treated parasites displayed numerous, often apposed, compartments of distinct dimensions, often filling large portions of the parasite cell volume (B – inset). MDC-positive parasite quantitation by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 9C) indicate that the β-lapachone derivative doubled autophagosome formation (P < 0.0001).

Fig. 9.

Detection of autophagic process by the probe monodansylcadaverine (MDC). Untreated parasites were poorly and diffusely labelled (A), whereas R72-treated cells displayed numerous and often closely apposed strongly labelled compartments (B). Insets show individual MDC-labelled cells. DMSO-treated parasites showed no alteration as compared to untreated cells (not shown). Quantitation of cells displaying monodansylcadaverine-labeled compartments by fluorescence microscopy (C). The frequency of parasites presenting MDC+ compartments was determined by counting of over 260 cells per group. About 36% of untreated control parasites presented MDC punctate labelling, whereas nearly 83% of parasites grown with 19 μM R72 showed. MDC-stained autophagosomes. Chi-square with Yates correction (1 degree of freedom), equals 7018.369 with P < 0.0001 (two-tailed, ***).

TEM images demonstrate the β-lapachone derivative triggered the biogenesis of autophagosomes presenting organelles such as mitochondria (Fig. 10A), membrane profiles and ribosome-like aggregated particles (Fig. 10B). Eventually the autophagosomes underwent cumulative fusion, giving rise to large compartments, ultimately leading to parasite cell rupture (Fig. 10C).

Fig. 10.

Autophagic vacuoles (AV) presenting mitochondrial portion (A–M), membrane profiles (B, arrow) and ribosome-like particles (B, *) were observed in R72-treated parasites. Note that cytoplasmic intact mitochondria may be still observed in the cytoplasm (A, arrow). Compartments lined by double membranes were often observed enveloping condensed mitochondrion fragment (C, thick arrow) and eventually the autophagosome fusion events (C, black arrowheads) formed huge compartments, containing membrane remnants (C, *), which could be associated to parasite cell surface continuity solution (thin arrow). Note condensed mitochondria displaying dilated cristae (C, white arrowheads).

4. Discussion

Here the T. cruzi epimastigote developmental form was assayed, although this insect-dwelling stage is unable to establish mammalian infection. Nevertheless it may furnish significant insights for the infection chemotherapy, as β-lapachone was reported to produce similar alterations in T. cruzi epimastigotes, amastigotes and trypomastigotes (Docampo et al., 1978), the developmental forms that multiply within mammalian host cells and spread via blood, respectively. In addition, different antiparasitic compounds may display similar effects upon epimastigotes and trypomastigotes and/or amastigotes, the developmental forms (Urbina et al., 1988, Urbina et al., 1993; Moreira et al., 2013a; Costa et al., 2011, Azeredo et al., 2014, Díaz et al., 2014; Jimenez et al., 2014; Veiga-Santos et al., 2014, Britta et al., 2015, Meira et al., 2015, Volpato et al., 2015, Beer et al., 2016) and the epimastigotes may therefore comprise and/or take part in experimental models (Kessler et al., 2013, Benítez et al., 2014, Sangenito et al., 2014, Wong-Baeza et al., 2015, Khare et al., 2015, Pessoa et al., 2016, Valera Vera et al., 2016). Thus, numerous studies perform screening experiments with epimastigotes and/or trypomastigotes further approach the selected active compounds in intracellular amastigotes (e.g. Pizzolatti et al., 2003, Molina-Garza et al., 2014, Legarda-Ceballos et al., 2015, Olivera et al., 2015) or in vivo.

The β-lapachone-induced oxygen intermediates are able to damage cell membranes giving rise to necrosis (Bey et al., 2013) and/or inducing caspase-dependent or independent apoptosis (Pink et al., 2000, Pardee et al., 2002). Nevertheless, lapachone-induced ROS generation was also shown to trigger autophagic process causing glioma cell death (Park et al., 2011). Autophagy was reported to be a programed (Green and Levine, 2014) or incidental (Proto et al., 2013) cell death process. Similarly ganglioside-induced ROS are involved in autophagic cell death of astrocytes (Hwang et al., 2010) and lipid rafts are involved in the process. The surface alteration revealed here by SEM and TEM in the parasite cytostome area may result from the different composition of this surface domain. Ultrastructural cytochemistry procedures demonstrated that the cytostome opening displays a different membrane composition and lectin labeling revealed the presence of glycoconjugates (Pimenta et al., 1989). This membrane area in T. cruzi was shown to function as lipid rafts (Corrêa et al., 2007). It was demonstrated that ROS can disrupt lipid rafts (Premasekharan et al., 2011) and these membrane domains are involved ethanol-induced oxidative stress in hepatocytes (Nourissat et al., 2008). Benzo[a]pyrene and ethanol trigger oxidative stress and lipid raft aggregation in rat hepatocytes (Collin et al., 2014). This effect is associated to lipid peroxidation and phospholipase C translocation into lipid rafts as well as enhanced membrane fluidity and lysosome membrane permeabilization and β-lapachone was also reported to disrupt lipid rafts in Giardia lamblia trophozoites (Corrêa et al., 2009).

Since the cytostome is involved in the parasite nutrition (Okuda et al., 1999), the β-lapachone derivative-mediated disorganization of this membrane domain may restrain the nutrient uptake by the cell, presumably triggering autophagy. The autophagic process comprises a homeostatic mechanism protecting different cell types from stress conditions (Heymann, 2006), such as antiparasitic drugs or xenobiotics (Vannier-Santos and De Castro, 2009, Souza-Neta et al., 2014), involved in T. cruzi nutritional stress and differentiation (Alvarez et al., 2008). Mitochondrial swelling and altered kDNA array were also reported on T. cruzi after incubation with a β-lapachone derivative (Menna-Barreto et al., 2007). The supernumerary basal bodies in R72-treated parasites, as this structure orchestrates trypanosomatid parasite cell division and differentiation (Vaughan and Gull, 2016). Supernumerary centrosomes are indicative of cell pathology and drug-induced stress may cause the biogenesis of multiflagellate T. cruzi (Grellier et al., 1999) and Leishmania amazonensis (Borges et al., 2005). Hydrogen peroxide (Chae et al., 2005) and ROS-mediated autophagy (Pannu et al., 2012) are associated to centrosome amplification. Oxidative stress triggers centrosome amplification in Drosophila cells (Park et al., 2014a, Park et al., 2014b) and takes part in HeLa cells centrosome organization (Bollineni et al., 2014) and human centrin 2 radiolytical oxidation causes centrosome duplication abnormalities (Blouquit et al., 2007). The kDNA alteration of R72-treated parasites maybe caused by the oxidative stress, as the ROS-producing mitochondria are also affected by naphthoquinones (reviewed in Menna-Barreto and de Castro, 2014) and lapachone was shown to affect Crithidia fasciculata kinetoplasts (Biscardi et al., 2001).

It is well-known that β-lapachone (Docampo et al., 1978, Boveris et al., 1978) and its derivatives (Gonçalves et al., 1980) lead to the generation of ROS such as superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide and ROS generation by R72-treated parasites was corroborated by DCFDA labeling by flow cytometry. Naphtoquinones, β-lapachone derivatives may trigger distinct cell death pathways in T. cruzi parasites including autophagic, apoptotic-like and necrosis (Menna-Barreto et al., 2009a, Menna-Barreto et al., 2009c) and so it was interesting to elucidate the mode of action involved in R72 selective trypanocidal activity. It was shown that a naphtoquinone derivative can not only produce ROS in the mitochondrion but also inhibit glycosomal enzymes glycerol kinase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Pieretti et al., 2013). Docampo et al. (1978), noticed a patchy chromatin distribution which presumably corresponds to the apoptosis-associated pycnosis well-known presently. Evidence of nuclear fragmentation and autophagosome formation may be detected in the micrographs presented in this early work. The β-lapachone action upon chromatin organization may be due to the direct damage by free radicals (Docampo et al., 1978) and modulation of DNA topoisomerase 1 (Pardee et al., 2002). 3-allyl-β-lapachone was assayed on T. cruzi epimastigotes and tripomastigotes, causing chromatin patchy distribution, mitochondrial disruption, associated to H2O2 production and lipid peroxidation (Gonçalves et al., 1980).

As DAPI was successfully employed for detection of nuclear fragmentation in diverse cell types (e.g. Hamel et al., 1996, Datta et al., 1997, Casiano et al., 1998, Krysko et al., 2001), including T. cruzi epimastigotas (Jimenez et al., 2008), we used the probe to detect nuclear fragmentation and it was observed in circa 1% of the R72-treated parasites. Nuclear fragmentation was also indicated by MET. The TUNEL assay also confirmed DNA fragmentation. Nevertheless the TUNEL technique fails to discriminate between apoptotic and necrotic cell death pathways (Grasl-Kraupp et al., 1995) as necrotic cells can also be labeled (Charriaut-Marlangue and Ben-Ari, 1995). As the TUNEL labeling was detected in over 90% of the cells (higher staining than the DNAse positive control), whereas the aV+ and PI− cells were solely 16.8% is reasonable to infer that most cells in autophagy and early apoptosis rapidly evolved to necrotic cell death, associated to DNA fragmentation. The chromatin condensation and nuclear protrusions/fragmentation as well as phosphatidylserine expression are consistent with apoptosis induction rather than necrosis, but these events were uncommon and the extent of necrosis based on PI labeling by flow cytometry of R72-treated parasites was circa 20% and may be underestimated since it was previously shown that primary necrotic cells may display annexin V-positive/PI-negative staining before becoming PI-positive (Sawai and Domae, 2011) and DCFDA indicates that ROS generation proceeded up to at least 72 h.

Oxidative stress may play multiple roles in autophagic process. ROS production is generally associated with increased autophagy (Bolisetty and Jaimes, 2013, Wen et al., 2013), in pathways dependent on PI3K, beclin, p53, p38 ERK, Atg5, Atg4 etc., whereas HO•- causes lysosomal dysfunction, inhibiting autophagy (Dodson et al., 2013). The trypanosomatid apoptosis does not follow canonical pathways, lacking regulators/effectors, such as caspases, Bcl-2 or TNF-related receptors (Smirlis and Soteriadou, 2011) and the occurrence of programmed death pathways in protozoa remains controversial (Proto et al., 2013). β-lapachone triggers necrosis via activation of PARP (poly (ADP-ribosyl) polymerase-1), a main regulator of the DNA damage response pathway (Herceg and Wang, 2001). PARP is involved in β-lapachone-induced necrotic cell death in human osteosarcoma cells (Liu et al., 2002) and it was recently shown that necrosis may be dependent on JNK or Ca2+/calpain pathways (Douglas and Baines, 2014).

The β-lapachone-mediated ROS production in a catalase-sensitive way triggers autophagic cancer cell death (Bey et al., 2013), as well as programmed necrosis or necroptosis in a mechanism involving receptor interacting protein (RIP)1, PARP-1 and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF; Park et al., 2014a, Park et al., 2014b). In this regard, it is noteworthy that PARP activity was reported in all T. cruzi developmental stages (Fernández Villamil et al., 2008).

The lapachone-induced mitochondrial dilation and autophagy (mitophagy) mechanisms depend on the production of ROS (Salomão et al., 2013). The R72-treated parasites not only removed mitochondrial portions by mitophagy, but also showed mitochondria in the condensed configuration with distended cristae, long known to be metabolically inactive (Hackenbrock et al., 1971). β-lapachone action is largely dependent on calcium influx that may lead to mitochondrial membrane depolarization (Tagliarino et al., 2001), possibly inducing mitophagy in R72-treated parasites. It is noteworthy that calcium is involved in apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy (Giorgi et al., 2008) and may both trigger and suppress autophagy/mitophagy (East and Campanella, 2013).

The observation of parasites displaying mitochondrial portions within autophagic vacuoles and parts of the organelle still in the cytoplasm indicate that this protozoan also performs mitochondrial fission a processes required for mitophagy (Kim et al., 2007), particularly in trypanosomatid parasite cells that display a single mitochondrion (Vannier-Santos et al., 2002). Similarly a triazolic naphthofuranquinone was shown to induce autophagy in T. cruzi (Fernandes et al., 2012). This process may be caused by β-lapachone-mediated ROS production as oxidative stress was shown to trigger mitochondrial fission and mitophagy (Frank et al., 2012). Furthermore, Mitochondrial oxidative stress is involved in astrocyte necrotic cell death (Jacobson and Duchen, 2002) and a β-lapachone derivative was reported to produce apoptosis and necrosis simultaneously in HL-60 cells (Araújo et al., 2012). In addition, the secondary necrosis may comprise the natural outcome of apoptosis (Silva, 2010) and necrosis subsequently takes place following apoptosis in HeLa cells (Xie et al., 2013), epithelial cells incubated with Candida albicans (Villar and Zhao, 2010) and in the Cnidarian Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus (Buss et al., 2012) in a process that may be termed “secondary necrosis” (Silva et al., 2008).

Formerly understood as discrete cell death pathways, now apoptosis, autophagy and necrosis/necroptosis are seen as interdependent showing an intricate regulation and cross-talk (Chaabane et al., 2013, Jain et al., 2013). ATP depletion may switch human T cell death from apoptosis to necrosis (Leist et al., 1997). In this regard the naphthoquinone effects on T. cruzi were shown to be exerted on mitochondria (Menna-Barreto et al., 2009a, Menna-Barreto et al., 2009b, Menna-Barreto et al., 2009c, Menna-Barreto and de Castro, 2014), where ROS are produced by β-lapachone treated T. cruzi (Boveris et al., 1978). Therefore mitochondrial function arrest may comprise an antioxidant defence (Oliveira and Oliveira, 2002) as reported for Aedes aegypti muscle (Gonçalves et al., 2009). Hence, mitophagy and mitochondrial loss of function may lead to metabolic deficit, possibly promoting parasite necrosis. β-lapachone and its derivatives were shown to trigger apoptosis and autophagy in both parasites (Docampo et al., 1978, Menna-Barreto et al., 2009a, Salomão et al., 2013) and tumor cells (Li et al., 1999, Li et al., 2003; Park et al., 2011, Di Rosso et al., 2013), involving the formation of ROS (Araújo et al., 2012, Salomão et al., 2013).

Necrosis may be preceded (Koike et al., 1982) or mediated (Joshi et al., 2012) by autophagy in pancreatic cells and breast cancer cells, respectively. Furthermore, autophagy is required for necrosis in Caenorhabditis elegans (Samara et al., 2008). The ultrastructural analysis reported here indicate that R72-induced autophagy may lead to cumulative vesicle fusion, culminating in fusion/disrupture of parasite cell membrane. The cumulative fusion of compartments such as autophagosomes, indicated by MDC labelling and TEM, apparently led to the lysis of R72-treated parasites. Similarly, organelle fusion events taking place during autophagic process may cause in necroptosis in human polymorphonuclear cells (Mihalache et al., 2011). Thus, exacerbated autophagy may lead to incidental necrosis, corroborating the hypothesis of Proto et al. (2013). Interestingly necroptosis may depend on autophagy as reported in leukemia cells (Bonapace et al., 2010). Additionally the lipid peroxidation caused by ROS production may enhance membrane fusogenicity of cellular compartments (Almeida et al., 1994), possibly promoting incidental autophagic parasite cell death. A β-lapachone derivative was shown to produce catastrophic vacuolization in tumor cells (Ma et al., 2015). The remarkable compartment fusion in R72-treated parasites may lead to necrosis via cumulative fusion as in the compound exocytosis reported in eosinophil leukocytes (Scepek et al., 1994, Hafez et al., 2003).

The present data indicate that selective β-lapachone derivatives may comprise useful tools in development of trypanocidal drugs and that parasite architecture approach may elucidate the modes of action of antiparasitic natural products.

Acknowledgments

Sponsored by: CNPq, PROCAD/Capes PP-SUS, PROEP, INCT-INPeTAm, FAPESB, PRONEX/MCT.

References

- Aguiar C., Batista A.M., Pavan T.B., Almeida E.A., Guariento M.E., Wanderley J.S., Costa Serological profiles and evaluation of parasitaemia by PCR and blood culture in individuals chronically infected by Trypanosoma cruzi treated with benzonidazole. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2012;17:368–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida M.T., Ramalho-Santos J., Oliveira C.R., de Lima M.C. Parameters affecting fusion between liposomes and synaptosomes. Role of proteins, lipid peroxidation, pH and temperature. J. Membr. Biol. 1994;142:217–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00234943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez V.E., Kosec G., Sant'Anna C., Turk V., Cazzulo J.J., Turk B. Autophagy is involved in nutritional stress response and differentiation in Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:3454–3464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708474200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo A.J., De Souza A.A., Da Silva Júnior E.N., Marinho-Filho J.D., de Moura M.A., Rocha D.D., Vasconcellos M.C., Costa C.O., Pessoa C., Moraes De, Ferreira V.S., De Abreu F.C., Pinto A.V., Montenegro R.C., Costa-Lotufo L.V., Goulart M.O. Growth inhibitory effects of 3'-nitro-3-phenylamino nor-beta-lapachone against HL-60, a redox-dependent mechanism. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2012;26:585–589. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azeredo C.M., Santos T.G., Maia B.H., Soares M.J. In vitro biological evaluation of eight different essential oils against Trypanosoma cruzi, with emphasis on Cinnamomum verum essential oil. BMC Complem. Altern. Med. 2014;14:309. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel L.C., Montalto de Mecca M., Fanelli S.L., Rodriguez C.C., Diaz E.G., Castro J.A. Early nifurtimox-induced biochemical and ultrastructural alterations in rat heart. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2007;26:781–788. doi: 10.1177/0960327107084540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer M.F., Frank F.M., Elso G.O., Bivona E.A., Cerny N., Giberti G., Malchiodi L., Martino S.V., Alonso M.R., Sülsen P.V., Cazorla S.I. Trypanocidal and leishmanicidal activities of flavonoids isolated from Stevia satureiifolia var. satureiifolia. Pharm. Biol. 2016;54:2188–2195. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2016.1150304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belorgey D., Lanfranchi D.A., Davioud-Charvet E. 1,4-naphthoquinones and other NADPH-dependent glutathione reductase-catalyzed redox cyclers as antimalarial agents. Curr. Pharma. Des. 2013;19:2512–2528. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319140003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benítez D., Casanova G., Cabrera G., Galanti N., Cerecetto H., González M. Initial studies on mechanism of action and cell death of active N-oxide-containing heterocycles in Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes in vitro. Parasitol. 2014;141:682–696. doi: 10.1017/S003118201300200X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardino A.M., Da Silva Pinheiro L.C., Rodrigues C.R., Loureiro N.I., Castro H.C., Lanfredi-Rangel A., Sabatini-Lopes J., Borges J.C., Carvalho J.M., Romeiro G.A., Ferreira V.F., Frugulhetti I.C., Vannier-Santos M.A. Design, synthesis, SAR, and biological evaluation of new 4-(phenylamino)thieno[2,3-b]pyridine derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:5765–5770. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey E.A., Reinicke K.E., Srougi M.C., Varnes M., Anderson V.E., Pink J.J., Li L.S., Patel M., Cao L., Moore Z., Rommel A., Boatman M., Lewis C., Euhus D.M., Bornmann W.G., Buchsbaum D.J., Spitz D.R., Gao J., Boothman D.A. Catalase abrogates β-lapachone induced PARP1 hyperactivation-directed programmed necrosis in NQO1-positive breast cancers. Molec. Cancer Res. 2013;12:2110–2120. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscardi A.M., Lopez L.M., de Pahn E.M., Pellegrino de Iraldi A., Stoppani A.O. Effect of dyskinetoplastic agents on ultrastructure and oxidative phosphorylation in Crithidia fasciculata. Biocell. 2001;25:43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouquit Y., Duchambon P., Brun E., Marco S., Rusconi F., Sicard-Roselli C. High sensitivity of human centrin 2 toward radiolytical oxidation: C-terminal tyrosinyl residue as the main target. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;43:216–228. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolisetty S., Jaimes E.A. Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species: physiology and pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:6306–6344. doi: 10.3390/ijms14036306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollineni R.C., Hoffmann R., Fedorova M. Proteome-wide profiling of carbonylated proteins and carbonylation sites in HeLa cells under mild oxidative stress conditions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;68:186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonapace L., Bornhauser B.C., Schmitz M., Cario G., Ziegler U., Niggli F.K., Schäfer B.W., Schrappe M., Stanulla M., Bourquin J.P. Induction of autophagy-dependent necroptosis is required for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells to overcome glucocorticoid resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2010;120:1310–1323. doi: 10.1172/JCI39987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges V.M., Lopes U.G., De Souza W., Vannier-Santos M.A. Cell structure and cytokinesis alterations in multidrug-resistant Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. Parasitol. Res. 2005;95:90–96. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveris A., Docampo R., Turrens J.F., Stoppani A.O. Effect of β-lapachone on superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide production in Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochem. J. 1978;175:431–439. doi: 10.1042/bj1750431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britta E.A., Scariot D.B., Falzirolli H., da Silva C.C., Ueda-Nakamura T., Dias Filho B.P., Borsali R., Nakamura C.V. 4-Nitrobenzaldehyde thiosemicarbazone: a new compound derived from S-(-)-limonene that induces mitochondrial alterations in epimastigotes and trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitol. 2015;142:978–988. doi: 10.1017/S0031182015000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss L.W., Anderson C., Westerman E., Kritzberger C., Poudyal M., Moreno M.A., Lakkis F.G. Allorecognition triggers autophagy and subsequent necrosis in the cnidarian Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus. PLoS One. 2012;7:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho L.H., Rocha E.M., Raslan D.S., Oliveira A.B., Krettli A.U. In vitro activity of natural and synthetic naphthoquinones against erythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1988;21:485–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casiano C.A., Ochs R.L., Tan E.M. Distinct cleavage products of nuclear proteins in apoptosis and necrosis revealed by autoantibody probes. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:183–190. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro J.A., Meca M.M., Bartel I.C. Toxic side effects of drugs used to treat Chaga's disease (American trypanosomiasis) Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2006;25:471–479. doi: 10.1191/0960327106het653oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaabane W., User S.D., El-Gazzah M., Jaksik R., Sajjadi E., Rzeszowska-Wolny J., Los M.J. Autophagy, apoptosis, mitoptosis and necrosis: interdependence between those pathways and effects on cancer. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2013;61:43–58. doi: 10.1007/s00005-012-0205-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae S., Yun C., Um H., Lee J.H., Cho H. Centrosome amplification and multinuclear phenotypes are induced by hydrogen peroxide. Exp. Mol. Med. 2005;37:482–487. doi: 10.1038/emm.2005.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charriaut-Marlangue C., Ben-Ari Y. A cautionary note on the use of the TUNEL stain to determine apoptosis. Neuroreport. 1995;7:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin A., Hardonnière K., Chevanne M., Vuillemin J., Podechard N., Burel A., Dimanche-Boitrel M.T., Lagadic-Gossmann D., Sergent O. Cooperative interaction of benzo[a]pyrene and ethanol on plasma membrane remodeling is responsible for enhanced oxidative stress and cell death in primary rat hepatocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;72:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa G., Vilela R., Menna-Barreto R.F., Midlej V., Benchimol M. Cell death induction in Giardia lamblia: effect of beta-lapachone and starvation. Parasitol. Int. 2009;58:424–437. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa J.R., Atella G.C., Batista M.M., Soares M.J. Transferrin uptake in Trypanosoma cruzi is impaired by interference on cytostome-associated cytoskeleton elements and stability of membrane cholesterol, but not by obstruction of clathrin-dependent endocytosis. Exp. Parasitol. 2007;119:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E.V., Pinheiro M.L., de Souza A.D., Barison A., Campos F.R., Valdez R.H., Ueda-Nakamura T., Filho B.P., Nakamura C.V. Trypanocidal activity of oxoaporphine and pyrimidine-β-carboline alkaloids from the branches of Annona foetida Mart. (Annonaceae) Mol. 2011;16:9714–9720. doi: 10.3390/molecules16119714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva Júnior E.N., De Souza M.C., Fernandes M.C., Menna-Barreto R.F., Pinto Mdo C., De Assis Lopes F., De Simone C.A., Andrade C.K., Pinto A.V., Ferreira V.F., De Castro S.L. Synthesis and anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity of derivatives from nor-lapachones and lapachones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:5030–5038. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta R., Kojima H., Yoshida K., Kufe D. Caspase-3-mediated cleavage of protein kinase C theta in induction of apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:20317–20320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Andrade-Neto V.F., Goulart M.O., Da Silva Filho J.F., Da Silva M.J., Pinto Mdo C., Pinto A.V., Zalis M.G., Carvalho L.H., Krettli A.U. Antimalarial activity of phenazines from lapachol, beta-lapachone and its derivatives against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro and Plasmodium berghei in vivo. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;8:1145–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Castro C.R., De Mecca M.M., Fanelli S.L., De Ferreyra E.C., Díaz E.G., Castro J.A. Benznidazole-induced ultrastructural and biochemical alterations in rat esophagus. Toxicology. 2003;191:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pahn E.M., Molina Portela M.P., Stoppani A.O. Effect of quinones and nitrofurans on Trypanosoma mega and Crithidia fasciculata. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 1988;20:107–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza W. From the cell biology to the development of new chemotherapeutic approaches against trypanosomatids, dreams and reality. Kinetopl. Biol. Dis. 2002;31:1–21. doi: 10.1186/1475-9292-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Rosso M.E., Barreiro Arcos M.L., Elingold I., Sterle H., Baptista Ferreira S., Ferreira V.F., Galleano M., Cremaschi G., Dubin M. Novel o-naphthoquinones induce apoptosis of EL-4 T lymphoma cells through the increase of reactive oxygen species. Toxicol. Vitro. 2013;27:2094–2104. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz M.V., Miranda M.R., Campos-Estrada C., Reigada C., Maya J.D., Pereira C.A., López-Muñoz R. Pentamidine exerts in vitro and in vivo anti Trypanosoma cruzi activity and inhibits the polyamine transport in Trypanosoma cruzi. Acta Trop. 2014;134:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogo E.B., Dias G.G., Rodrigues B.L., Guimarães T.T., Valença W.O., Camara C.A., De Oliveira R.N., Da Silva M.G., Ferreira V.F., De Paiva Y.G., Goulart M.O., Menna-Barreto R.F., De Castro S.L., Da Silva Júnior E.N. Synthesis and anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity of naphthoquinone-containing triazoles: electrochemical studies on the effects of the quinoidal moiety. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;1:6337–6348. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docampo R., De Souza W., Cruz F.S., Roitman I., Cover B., Gutteridge W.E. Ultrastructural alterations and peroxide formation induced by naphthoquinones in different stages of Trypanosoma cruzi. Z. Parasitenkd. 1978;57:189–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00928032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson M., Darley-Usmar V., Zhang J. Cellular metabolic and autophagic pathways: traffic control by redox signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;63:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas D.L., Baines C.P. PARP1-mediated necrosis is dependent on parallel JNK and Ca2+/calpain pathways. J. Cell Sci. 2014;127:4134–4145. doi: 10.1242/jcs.128009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East D.A., Campanella M. Ca2+ in quality control: an unresolved riddle critical to autophagy and mitophagy. Autophagy. 2013;9:1710–1719. doi: 10.4161/auto.25367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes M.C., Da Silva E.N., Jr., Pinto A.V., De Castro S.L., Menna-Barreto R.F.S. A novel triazolic naphthofuranquinone induces autophagy in reservosomes and impairment of mitosis in Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitology. 2012;139:26–36. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011001612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Villamil S.H., Baltanás R., Alonso G.D., Vilchez Larrea S.C., Torres H.N., Flawiá M.M. TcPARP: a DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase from Trypanosoma cruzi. Int. J. Parasitol. 2008;38:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira S.B., Salomão K., Silva C.F., Pinto A.V., Kaiser C.R., Pinto A.C., Ferreira V.F., De Castro S.L. Synthesis and anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity of β-lapachone analogues. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:3071–3077. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournet A., Muñoz V. Natural products as trypanocidal, antileishmanial and antimalarial drugs. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002;2:1215–1237. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank M., Duvezin-Caubet S., Koob S., Occhipinti A., Jagasia R., Petcherski A., Ruonala M.O., Priault M., Salin B., Reichert A.S. Mitophagy is triggered by mild oxidative stress in a mitochondrial fission dependent manner. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1823:2297–2310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia S., Ramos C.O., Senra J.F., Vilas-Boas F., Rodrigues M.M., Campos-de-Carvalho A.C., Ribeiro-Dos-Santos R., Soares M.B. Treatment with benznidazole during the chronic phase of experimental Chagas' disease decreases cardiac alterations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1521–1528. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1521-1528.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117–171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi C., Romagnoli A., Pinton P., Rizzuto R. Ca2+ signaling, mitochondria and cell death. Curr. Mol. Med. 2008;8:119–130. doi: 10.2174/156652408783769571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goijman S.G., Stoppani A.O. Effects of β-lapachone, a peroxide-generating quinone, on macromolecule synthesis and degradation in Trypanosoma cruzi. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1985;240:273–280. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves A.M., Vasconcellos M.E., Docampo R., Cruz F.S., de Souza W., Leon W. Evaluation of the toxicity of 3-allyl-beta-lapachone against Trypanosoma cruzi bloodstream forms. Molec. Biochem. Parasitol. 1980;1:167–176. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(80)90015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves R.L., Machado A.C., Paiva-Silva G.O., Sorgine M.H., Momoli M.M., Oliveira J.H., Vannier-Santos M.A., Galina A., Oliveira P.L., Oliveira M.F. Blood-feeding induces reversible functional changes in flight muscle mitochondria of Aedes aegypti mosquito. PLoS One. 2009;4:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasl-Kraupp B., Ruttkay-Nedecky B., Koudelka H., Bukowska K., Bursch W., Schulte-Hermann R. In situ detection of fragmented DNA (TUNEL assay) fails to discriminate among apoptosis, necrosis, and autolytic cell death: a cautionary note. Hepatology. 1995;21:1465–1468. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840210534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D.R., Levine B. To be or not to be? How selective autophagy and cell death govern cell fate. Cell. 2014;157:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grellier P., Sinou V., Garreau-de Loubresse N., Bylèn E., Boulard Y., Schrével J. Selective and reversible effects of Vinca alkaloids on Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigote forms: blockage of cytokinesis without inhibition of the organelle duplication. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 1999;42:36–47. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1999)42:1<36::AID-CM4>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães T.T., Pinto Mdo C., Lanza J.S., Melo M.N., Do Monte-Neto R.L., De Melo I.M., Diogo E.B., Ferreira V.F., Camara C.A., Valença W.O., De Oliveira R.N., Frézard F., Da Silva E.N., Jr. Potent naphthoquinones against antimony-sensitive and -resistant Leishmania parasites: synthesis of novel α- and nor-α lapachone-based 1,2,3-triazoles by copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;63:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackenbrock C.R., Rehn T.G., Weinbach E.C., Lemasters J.J. Oxidative phosphorylation and ultrastructural transformation in mitochondria in the intact ascites tumor cell. J. Cell Biol. 1971;51:123–137. doi: 10.1083/jcb.51.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafez I., Stolpe A., Lindau M. Compound exocytosis and cumulative fusion in eosinophils. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:44921–44928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel W., Magnelli L., Chiarugi V.P., Israel M.A. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir-mediated apoptotic death of bystander cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2697–2702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasslocher-Moreno A.M., do Brasil P.E., de Sousa A.S., Xavier S.S., Chambela M.C., da Silva G.M.S. Safety of benznidazole use in the treatment of chronic Chagas' disease. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:1261–1266. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herceg Z., Wang Z.Q. Functions of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in DNA repair, genomic integrity and cell death. Mutat. Res. 2001;477:97–110. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann D. Autophagy: a protective mechanism in response to stress and inflammation. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2006;7:443–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J., Lee S., Lee J.T., Kwon T.K., Kim D.R., Kim H., Park H.C., Suk K. Gangliosides induce autophagic cell death in astrocytes. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 2010;159:586–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi E., Ueda-Nakamura T., Dias Filho B.P., Veiga Júnior V.F., Nakamura C.V. Natural products and Chagas' disease: a review of plant compounds studied for activity against Trypanosoma cruzi. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011;28:809–823. doi: 10.1039/c0np00069h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J., Duchen M.R. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and cell death in astrocytes–requirement for stored Ca2+ and sustained opening of the permeability transition pore. J. Cell. Molec. Med. 2002;115:1175–1188. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M.V., Paczulla A.M., Klonisch T., Dimgba F.N., Rao S.B., Roberg K., Schweizer F., Lengerke C., Davoodpour P., Palicharla V.R., Maddika S., Łos M. Interconnections between apoptotic, autophagic and necrotic pathways: implications for cancer therapy development. J. Cell. Molec. Med. 2013;17:12–29. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez V., Paredes R., Sosa M.A., Galanti N. Natural programmed cell death in T. cruzi epimastigotes maintained in axenic cultures. J. Cell Biochem. 2008;105:688–698. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez V., Kemmerling U., Paredes R., Maya J.D., Sosa M.A., Galanti N. Natural sesquiterpene lactones induce programmed cell death in Trypanosoma cruzi: a new therapeutic target? Phytomedicine. 2014;21:1411–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi P., Chakraborti S., Ramirez-Vick J.E., Ansari Z.A., Shanker V., Chakrabarti P., Singh S.P. The anticancer activity of chloroquine-gold nanoparticles against MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2012;95:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.L., Gradia D.F., Pontello Rampazzo R.C., Lourenço É.E., Fidêncio N.J., Manhaes L., Probst C.M., Ávila A.R., Fragoso S.P. Stage-regulated GFP Expression in Trypanosoma cruzi: applications from host-parasite interactions to drug screening. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khare S., Roach S.L., Barnes S.W., Hoepfner D., Walker J.R., Chatterjee A.K., Neitz R.J., Arkin M.R., McNamara C.W., Ballard J., Lai Y., Fu Y., Molteni V., Yeh V., McKerrow J.H., Glynne R.J., Supek F. Utilizing chemical genomics to identify cytochrome b as a novel drug target for chagas disease. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005058. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I., Rodriguez-Enriquez S., Lemasters J.J. Selective degradation of mitochondria by mitophagy. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;462:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike H., Steer M.L., Meldolesi J. Pancreatic effects of ethionine: blockade of exocytosis and appearance of crinophagy and autophagy precede cellular necrosis. Am. J. Physiol. 1982;242:G297–G307. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1982.242.4.G297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysko D.V., Roels F., Leybaert L., D'Herde K. Mitochondrial transmembrane potential changes support the concept of mitochondrial heterogeneity during apoptosis. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2001;49:1277–1284. doi: 10.1177/002215540104901010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legarda-Ceballos A.L., del Olmo E., López-Abán J., Escarcena R., Bustos L.A., Fonseca-Berzal C., Gómez-Barrio A., Dib J.C., San Feliciano A., Muro A. Trypanocidal activity of long chain diamines and aminoalcohols. Molecules. 2015;20:11554–11568. doi: 10.3390/molecules200611554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leist M., Single B., Castoldi A.F., Kühnle S., Nicotera P. Intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) concentration: a switch in the decision between apoptosis and necrosis. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:1481–1486. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.8.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.J., Li Y.Z., Pinto A.V., Pardee A.B. Potent inhibition of tumor survival in vivo by β-lapachone plus taxol: combining drugs imposes different artificial checkpoints. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;9:13369–13374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Sun X., LaMont J.T., Pardee A.B., Li C.J. Selective killing of cancer cells by beta -lapachone: direct checkpoint activation as a strategy against cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2003;100:2674–2678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0538044100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T.J., Lin S.Y., Chau Y.P. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation attenuates beta-lapachone-induced necrotic cell death in human osteosarcoma cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2002;182:116–125. doi: 10.1006/taap.2002.9438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Lim C., Sacher J.R., Van Houten B., Qian W., Wipf P. Mitochondrial targeted β-lapachone induces mitochondrial dysfunction and catastrophic vacuolization in cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:4828–4833. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.06.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta-Guedes P.M., Gutierrez F.R., Nascimento M.S., Do-Valle-Matta M.A., Silva J.S. Antiparasitical chemotherapy in Chagas' disease cardiomyopathy: current evidence. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2012;17:1057–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes D., Valentim C., Oliveira M.F., Vannier-Santos M.A. Putrescine analogue cytotoxicity against Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitol. Res. 2006;98:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-0010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meira C.S., Guimarães E.T., Dos Santos J.A., Moreira D.R., Nogueira R.C., Tomassini T.C., Ribeiro I.M., de Souza C.V., Ribeiro Dos Santos R., Soares M.B. In vitro and in vivo antiparasitic activity of Physalis angulata L. concentrated ethanolic extract against Trypanosoma cruzi. Phytom. 2015;22:969–974. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menna-Barreto R.F., de Castro S.L. The double-edged sword in pathogenic trypanosomatids: the pivotal role of mitochondria in oxidative stress and bioenergetics. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:614014. doi: 10.1155/2014/614014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menna-Barreto R.F., Corrêa J.R., Cascabulho C.M., Fernandes M.C., Pinto A.V., Soares M.J., De Castro S.L. Naphthoimidazoles promote different death phenotypes in Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitology. 2009;136:499–510. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009005745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menna-Barreto R.F., Corrêa J.R., Pinto A.V., Soares M.J., de Castro S.L. Mitochondrial disruption and DNA fragmentation in Trypanosoma cruzi induced by naphthoimidazoles synthesized from β-lapachone. Parasitol. Res. 2007;101:895–905. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0556-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menna-Barreto R.F., Goncalves R.L., Costa E.M., Silva R.S., Pinto A.V., Oliveira M.F., De Castro S.L. The effects on Trypanosoma cruzi of novel synthetic naphthoquinones are mediated by mitochondrial dysfunction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47:644–653. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menna-Barreto R.F., Henriques-Pons A., Pinto A.V., Morgado-Diaz J.A., Soares M.J., De Castro S.L. Effect of a β-lapachone-derived naphthoimidazole on Trypanosoma cruzi: identification of target organelles. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005;56:1034–1041. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menna-Barreto R.F., Salomão K., Dantas A.P., Santa-Rita R.M., Soares M.J., Barbosa H.S., de Castro S.L. Different cell death pathways induced by drugs in Trypanosoma cruzi: an ultrastructural study. Micron. 2009;40:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalache C.C., Yousefi S., Conus S., Villiger P.M., Schneider E.M., Simon H.U. Inflammation-associated autophagy-related programmed necrotic death of human neutrophils characterized by organelle fusion events. J. Immunol. 2011;1:6532–6542. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Garza Z.J., Bazaldúa-Rodríguez A.F., Quintanilla-Licea R., Galaviz-Silva L. Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity of 10 medicinal plants used in northeast Mexico. Acta Trop. 2014;136:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira T.L.B., Barbosa A.F., Veiga-Santos P., Henriques C., Henriques-Pons A., Galdino S.L., de Lima M.C., Pitta Ida R., de Souza W., de Carvalho T.M. Effect of thiazolidine LPSF SF29 on the growth and morphology of Trypanosoma cruzi. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2013;41:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira O.C., Ramírez J.D., Velázquez E., Melo M.F., Lima-Ferreira C., Guhl F., Sosa-Estani S., Marin-Neto J.A., Morillo C.A., Britto C. Towards the establishment of a consensus real-time qPCR to monitor Trypanosoma cruzi parasitemia in patients with chronic Chagas disease cardiomyopathy: a substudy from the Benefit trial. Acta Trop. 2013;125:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D.J., Cragg G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourissat P., Travert M., Chevanne M., Tekpli X., Rebillard A., Le Moigne-Müller G., Rissel M., Cillard J., Dimanche-Boitrel M.T., Lagadic-Gossmann D., Sergent O. Ethanol induces oxidative stress in primary rat hepatocytes through the early involvement of lipid raft clustering. Hepatology. 2008;47:59–70. doi: 10.1002/hep.21958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda K., Esteva M., Segura L.E., Bijovsky The cytostome of Trypanosoma cruzi epmastigotes is associated with the flagellar complex. Exp. Parasitol. 1999;92:223–231. doi: 10.1006/expr.1999.4419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira P.L., Oliveira M.F. Vampires, Pasteur and reactive oxygen species. Is the switch from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism a preventive antioxidant defence in blood-feeding parasites? FEBS Lett. 2002;525:3–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera G.C., Postan M., González M.N. Effects of artesunate against Trypanosma cruzi. Exp. Parasit. 2015;156:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannu V., Rida P.C., Ogden A., Clewley R., Cheng A., Karna P., Lopus M., Mishra R.C., Zhou J., Aneja R. Induction of robust de novo centrosome amplification, high-grade spindle multipolarity and metaphase catastrophe: a novel chemotherapeutic approach. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e346. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee A.B., Li Y.Z., Li C.J. Cancer therapy with β-lapachone. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2002;2:227–242. doi: 10.2174/1568009023333854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.S., Pyo J.H., Na H.J., Jeon H.J., Kim Y.S., Arking R., Yoo M.A. Increased centrosome amplification in aged stem cells of the Drosophila midgut. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;450:961–965. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E.J., Choi K.S., Kwon T.K. β-Lapachone-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation mediates autophagic cell death in glioma U87 MG cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2011;15:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E.J., Min K.J., Lee T.J., Yoo Y.H., Kim Y.S., Kwon T.K. β-Lapachone induces programmed necrosis through the RIP1-PARP-AIF-dependent pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep1 cells. Cell Death Dis. 2014;15:1–10. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Sacau E., Estévez-Braun A., Ravelo A.G., Gutiérrez Yapu D., Giménez T. Antiplasmodial activity of naphthoquinones related to lapachol and beta-lapachone. Chem. Biodivers. 2005;2:264–274. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200590009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa C.C., Ferreira É.R., Bayer-Santos E., Rabinovitch M., Mortara R.A., Real F. Trypanosoma cruzi differentiates and multiplies within chimeric parasitophorous vacuoles in macrophages coinfected with Leishmania amazonensis. Infect. Immun. 2016;84:1603–1614. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01470-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieretti S., Haanstra J.R., Mazet M., Perozzo R., Bergamini C., Prati F., Fato R., Lenaz G., Capranico G., Brun R., Bakker B.M., Michels P.A., Scapozza L., Bolognesi M.L., Cavalli A. Naphthoquinone derivatives exert their antitrypanosomal activity via a multi-target mechanism. PLoS Neglec. Trop. Dis. 2013;7:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimenta P.F., De Souza W., Souto-Padrón T., Pinto da Silva P. The cell surface of Trypanosoma cruzi, a fracture-flip, replica-staining label-fracture survey. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1989;50:263–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinazo M.J., Muñoz J., Posada E., López-Chejade P., Gállego M., Ayala E., Del Cacho E., Soy D., Gascon J. Tolerance of benznidazole in treatment of Chagas' disease in adults. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4896–4899. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00537-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pink J.J., Planchon S.M., Tagliarino C., Varnes M.E., Siegel D., Boothman D.A. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase activity is the principal determinant of betalapachone cytotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:5416–5424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A.V., Castro S.L. The trypanocidal activity of naphthoquinones: a review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;28:809–823. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A.V., Pinto C.N., Pinto Mdo C., Rita R.S., Pezzella C.A., De Castro S.L. Trypanocidal activity of synthetic heterocyclic derivatives of active quinones from Tabebuia sp. Arzneimittelforschung. 1997;47:74–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto C.N., Dantas A.P., De Moura K.C., Emery F.S., Polequevitch P.F., Pinto M.C., De Castro S.L., Pinto A.V. Chemical reactivity studies with naphthoquinones from Tabebuia with anti-trypanosomal efficacy. Arzneim. Forsch. - Drug Res. 2000;50:1120–1128. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1300337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzolatti M.G., Koga A.H., Grisard E.C., Steindel M. Trypanocidal activity of extracts from brazilian atlantic rain forest plant species. Phytomed. 2003;10:422–426. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premasekharan G., Nguyen K., Contreras J., Ramon V., Leppert V.J., Forman H.J. Iron-mediated lipid peroxidation and lipid raft disruption in low-dose silica-induced macrophage cytokine production. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;15:1184–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proto W.R., Coombs G.H., Mottram J.C. Cell death in parasitic protozoa: regulated or incidental? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;11:58–66. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues J.C., de Souza W. Ultrastructural alterations in organelles of parasitic protozoa induced by different classes of metabolic inhibitors. Curr. Pharma. Des. 2008;14:925–938. doi: 10.2174/138161208784041033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas C., Tapia R.A., Ciudad K., Armstrong V., Orellana M., Kemmerling U., Ferreira J., Maya J.D., Morello A. Trypanosoma cruzi: activities of lapachol and alpha- and beta-lapachone derivatives against epimastigote and trypomastigote forms. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:668–674. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomão K., De Santana N.A., Molina M.T., De Castro S.L., Menna-Barreto R.F. Trypanosoma cruzi mitochondrial swelling and membrane potential collapse as primary evidence of the mode of action of naphthoquinone analogues. BMC Microbiol. 2013;3:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samara C., Syntichaki P., Tavernarakis N. Autophagy is required for necrotic cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:105–112. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangenito L.S., Menna-Barreto R.F., D Avila-Levy C.M., Santos A.L., Branquinha M.H. Decoding the anti-Trypanosoma cruzi action of HIV peptidase inhibitors using epimastigotes as a model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos F.M., Lima W.G., Gravel A.S., Martins T.A., Talvani A., Torres R.M., Bahia M.T. Cardiomyopathy prognosis after benznidazole treatment in chronic canine Chagas' disease. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:1987–1995. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai H., Domae N. Discrimination between primary necrosis and apoptosis by necrostatin-1 in Annexin V-positive/propidium iodide-negative cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;5:569–573. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scepek S., Moqbel R., Lindau M. Compound exocytosis and cumulative degranulation by eosinophils and their role in parasite killing. Parasitol. Today. 1994;10:276–278. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M.T. Secondary necrosis: the natural outcome of the complete apoptotic program. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:4491–4499. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M.T., Do Vale A., Dos Santos N.M. Secondary necrosis in multicellular animals: an outcome of apoptosis with pathogenic implications. Apoptosis. 2008;13:463–482. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0187-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirlis D., Soteriadou K. Trypanosomatid apoptosis: 'Apoptosis' without the canonical regulators. Virulence. 2011;2:253–256. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.3.16278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Neta L.C., Menezes D., Lima M.S., Cerqueira M.D., Cruz F.G., Martins D., Vannier-Santos M.A. Modes of action of arjunolic acid and derivatives on Trypanosoma cruzi cells. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2014;14:1022–1032. doi: 10.2174/1568026614666140324122800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueth-Santiago V., Moraes J.B., Sobral Alves E.S., Vannier-Santos M.A., Freire-de-Lima C.G., Castro R.N., Mendes-Silva G.P., Del Cistia C.N., Magalhães L.G., Andricopulo A.D., Sant Anna C.M., Decoté-Ricardo D., Freire de Lima M.E. The effectiveness of natural diarylheptanoids against Trypanosoma cruzi: cytotoxicity, ultrastructural alterations and molecular modeling studies. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagboto S., Townson S. Antiparasitic properties of medicinal plants and other naturally occurring products. Adv. Parasitol. 2001;50:199–295. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(01)50032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliarino C., Pink J.J., Dubyak G.R., Nieminen A.L., Boothman D.A. Calcium is a key signaling molecule in beta-lapachone-mediated cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:19150–19159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina J.A., Lazardi K., Larralde G., Aguirre T., Piras M.M., Piras R. Synergistic effects of ketoconazole and SF-86327 on the proliferation of epimastigotes and amastigotes of Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1988;544:357–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb40421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina J.A., Lazardi K., Marchan E., Visbal G., Aguirre T., Piras M.M., Piras R., Maldonado R.A., Payares G., de Souza W. Mevinolin (lovastatin) potentiates the antiproliferative effects of ketoconazole and terbinafine against Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi: in vitro and in vivo studies. Antim. Agents Chemother. 1993;37:580–591. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.3.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valera Vera E.A., Sayé M., Reigada C., Damasceno F.S., Silber A.M., Miranda M.R., Pereira C.A. Resveratrol inhibits Trypanosoma cruzi arginine kinase and exerts a trypanocidal activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016;87:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannier-Santos M.A., De Castro S.L. Electron microscopy in antiparasitic chemotherapy: a (close) view to a kill. Curr. Drug Targets. 2009;10:246–260. doi: 10.2174/138945009787581168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannier-Santos M.A., Lins U. Cytochemical techniques and energy-filtering transmission electron microscopy applied to the study of parasitic protozoa. Biol. Proced. Online. 2001;3:8–18. doi: 10.1251/bpo19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannier-Santos M.A., Martiny A., De Souza W. Cell biology of Leishmania spp.: invading and evading. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2002;8:297–318. doi: 10.2174/1381612023396230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannier-Santos M.A., Menezes D., Oliveira M.F., de Mello F.G. The putrescine analogue 1,4-diamino-2-butanone affects polyamine synthesis, transport, ultrastructure and intracellular survival in Leishmania amazonensis. Microbiology. 2008;154:3104–3111. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/013896-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan S., Gull K. Basal body structure and cell cycle-dependent biogenesis in Trypanosoma brucei. Cilia. 2016;5:5. doi: 10.1186/s13630-016-0023-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga-Santos P., Reignault L.C., Huber K., Bracher F., De Souza W., De Carvalho T.M. Inhibition of NAD+-dependent histone deacetylases (sirtuins) causes growth arrest and activates both apoptosis and autophagy in the pathogenic protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitology. 2014;141:814–825. doi: 10.1017/S0031182013001704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar C.C., Zhao X.R. Candida albicans induces early apoptosis followed by secondary necrosis in oral epithelial cells. Molec. Oral Microbiol. 2010;25:215–225. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2010.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]