Abstract

Background

The transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) mediates cellular responses to pain, heat, or noxious stimuli by calcium influx; however, the cellular localization and function of TRPV1 in the cardiomyocyte is largely unknown. We studied whether myocardial injury is regulated by TRPV1 and whether we could mitigate reperfusion injury by limiting the calcineurin interaction with TRPV1.

Methods and Results

In primary cardiomyocytes, confocal and electron microscopy demonstrates that TRPV1 is localized to the mitochondria. Capsaicin, the specific TRPV1 agonist, dose‐dependently reduced mitochondrial membrane potential and was blocked by the TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine or the calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine. Using in silico analysis, we discovered an interaction site for TRPV1 with calcineurin. We synthesized a peptide, V1‐cal, to inhibit the interaction between TRPV1 and calcineurin. In an in vivo rat myocardial infarction model, V1‐cal given just prior to reperfusion substantially mitigated myocardial infarct size compared with vehicle, capsaicin, or cyclosporine (24±3% versus 61±2%, 45±1%, and 49±2%, respectively; n=6 per group; P<0.01 versus all groups). Infarct size reduction by V1‐cal was also not seen in TRPV1 knockout rats.

Conclusions

TRPV1 is localized at the mitochondria in cardiomyocytes and regulates mitochondrial membrane potential through an interaction with calcineurin. We developed a novel therapeutic, V1‐cal, that substantially reduces reperfusion injury by inhibiting the interaction of calcineurin with TRPV1. These data suggest that TRPV1 is an end‐effector of cardioprotection and that modulating the TRPV1 protein interaction with calcineurin limits reperfusion injury.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, calcineurin, cyclosporine, infarct size, ischemia, mitochondria, reperfusion, reperfusion injury, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

Subject Categories: Myocardial Biology, Ischemia, Myocardial Infarction, Cell Signalling/Signal Transduction

Introduction

Clinical trials to limit reperfusion injury during cardiac bypass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention have recently provided mixed results, suggesting that further deciphering of the molecular mechanism for reperfusion injury is important.1, 2, 3, 4 Since reperfusion injury is responsible for up to 50% of the myocardial infarct size when the heart undergoes ischemia–reperfusion,5 drugs to limit reperfusion injury would be beneficial and widely used. Because most injury at reperfusion is thought to occur during the initial few minutes, peptide therapeutics—with their qualities of a short half‐life (<30 minutes) and high selectivity for protein–protein interactions—may provide a viable means of limiting reperfusion injury by specifically targeting mitochondrial proteins for only a short time.

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) is a nonselective ion channel that preferentially gates calcium from pain stimuli. Besides the traditional activation of TRPV1 by pain, TRPV1 can act as a general sensor for cellular insults including hypoxia.6 The TRPV1 receptor is present in the nervous system and cardiac C fibers.7, 8 The TRPV1 agonist capsaicin, which exclusively activates only TRPV1, opens the inner gate of the TRPV1 channel near a conserved region called the TRP box.9 Capsaicin passes the lipid membrane and binds intracellularly to a cytosolic domain of the TRPV1 receptor.10

The TRPV1 channel exists in an open, closed, or inactive state. After TRPV1 activation and calcium influx, when TRPV1 is in an inactive state, it is reactivated by calcium‐dependent interaction with calcineurin. The interaction of calcineurin is important for regulation of the TRPV1 channel state, and the calcineurin–TRPV1 interaction is inducible on activation of TRPV111; however, a functional role in the cardiomyocyte for TRPV1 has not been described extensively. In this study, we determined that myocardial TRPV1 regulates mitochondrial membrane potential and reperfusion injury. We further identified a calcineurin–TRPV1 interaction site located at the C terminus of TRPV1. By using a peptide decoy to inhibit the inducible interaction of calcineurin with TRPV1, we tested whether we could substantially reduce damage from cardiac reperfusion injury.

Methods

Procedures and protocols were approved by the animal care and use committees at both Stanford University and the Medical College of Wisconsin. All animal studies conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male Sprague‐Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) aged 8 to 10 weeks and TRPV1 knockout rats (on the same genetic Sprague‐Dawley background; Horizon Discovery Group, Waterbeach, UK) were used for the studies outlined. The total number of animals used and the numbers included and excluded for this study (from which groups) are shown in Table S1.

Biochemical Techniques

The techniques used, including reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, Western blot, immunofluorescence, and transmission electron microscopy, are described in Data S1.

Drugs

Capsaicin, capsazepine, and cyclosporine were purchased commercially (Tocris Bioscience). Peptides were synthesized using microwave chemistry on a Liberty microwave peptide synthesizer (CEM Corp).12 We called the peptides V1‐Cal and A5‐Cal. Peptides were synthesized as 1 polypeptide with transactivator of transcription (TAT)47‐57 carrier in the following order: N‐terminus–TAT47‐57–spacer (Gly‐Gly)–cargo–C terminus. Peptide stability was assessed using a peptidase assay (Data S1).

Calcineurin Activity Assay

Either TAT (10 μmol/L) or V1‐cal (10 μmol/L) was incubated with calcineurin substrate and recombinant calcineurin. A colorimetric analysis measured the extent of free phosphate release from the substrate, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Calbiochem; EMD Millipore).

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

Using the protein Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST), the sequence AIXIXDTEXS (in which X is any amino acid) was queried for Homo sapiens and Rattus norvegicus. Matches for the sequence were identified.

In Silico Modeling

Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 3LL8 was imported into the UCSF Chimera program (University of California San Francisco), and the switch amino acid function was used to develop the TRPV1 C‐terminus sequence interaction with calcineurin A. Cyclophilin D was also incorporated by using PDB entry 1AUI. The location of the C‐terminus sequence of TRPV1 and calcineurin A were further evaluated in Swiss‐PdbViewer (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics). Selected residues were rendered in solid 3‐dimensional format.

Cardiomyocyte Isolation

Primary neonatal cardiomyocytes (PNCMs) were isolated from rat pups aged 1 to 3 days, as described previously.13 Adult cardiomyocytes were isolated from wild‐type or TRPV1 knockout male Sprague‐Dawley rats, as described previously.14

Live Cell Imaging

Mitochondrial membrane potential was determined using single‐cell analysis with an enclosed cellular chamber controlled for temperature, po 2, and pco 2. For these studies, cells were plated on glass coverslips (150 000 cells per dish; MatTek Corp) and maintained at a temperature of 37°C and 5% pco 2. Cells were washed once with DMEM (Invitrogen) and incubated with TMRE (tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester; Invitrogen) at 150 nmol/L or CMXRos (chloromethyl‐X‐rosamine; Invitrogen) at 0.5 μmol/L for 30 minutes at 37°C and then washed again with DMEM 10 minutes before being studied.15

Two protocols were performed in which cells were subjected (1) to specific treatments under normoxia (21% po 2) and (2) to hypoxia–reoxygenation. Images of individual cells were taken at baseline and used for normalization of the images acquired at 5‐minute intervals. For the hypoxia–reoxygenation model, cells were exposed to hypoxia (<1% po 2) for 30 minutes followed by reoxygenation for 30 minutes. Additional details are provided in Data S1.

Cell death for the hypoxia–reoxygenation model was determined by combined microscopic morphological and fluorescent assessment. Live cells exhibited unchanged cellular morphology and TMRE fluorescent stability. Dying cells exhibited characteristics of morphological contracture, assessed relative to the loss of initial cellular architecture before hypoxia and disruption of fluorescent TMRE signal.

H9C2 Cell Model of Ischemia–Reoxygenation

H9C2 cells (ATCC) at passages 18 to 24 were seeded at a density of 50 000 cells per well in 24‐well plates. Cells were serum starved for a period of 24 hours. After serum starvation, cells were treated with capsaicin (0.1–10 μmol/L) for 1 hour before being subjected to 6 hours of ischemia followed by 16 hours reoxygenation. Ischemia and reoxygenation were induced as described previously, and lactate dehydrogenase release was measured.16

Isolated Heart Model

The protocol used was described previously.12 Male Sprague‐Dawley rats were subjected to 30 minutes of global ischemia followed by 90 minutes of reperfusion. Left ventricular pressure balloons were made from plastic wrap, as described previously.12 The balloons were connected to a pressure transducer (MLT‐0699; ADI Instruments) to measure ventricular hemodynamics including end‐diastolic pressure, left ventricular developed pressure, and heart rate. Myocardial infarct size was also determined. Creatine phosphokinase was also measured during the first 30 minutes of reperfusion, as described previously.14

In Vivo Myocardial Infarction Rodent Model

The model was described previously in a number of publications.17, 18 All drugs given were administered through the internal jugular vein. The dose of cyclosporine given was chosen based on clinical trial dosing.3, 4 The carotid artery was cannulated and used to measure blood pressure and heart rate. After stabilization, rodents were given treatments as described while subjected to 30 minutes of left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion followed by 2 hours of reperfusion. Core body temperature was monitored rectally. Hemodynamics and infarct size were assessed.

Statistical Analysis

For animal studies, an experimental group size of 6 animals was determined to be necessary to achieve at least 15% minimal difference in myocardial infarct size (α<0.05 and 80% power). Furthermore, several statistical tests were used for the study, and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software). When only 2 groups were compared, a 2‐tailed Student t test was used. For end‐point assays, a 1‐way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction for multiplicity was used to compare each group with the control group. A 2‐way ANOVA was used to determine significance for hemodynamic parameters and to determine changes in significance in mitochondrial membrane potential for a drug intervention over time. When the 2‐way ANOVA interaction term was not significant, further interpretation occurred by examining the individual differences with a Bonferroni post hoc test, and terms identified as significant were reported. All groups were reported as mean±SEM. Statistical significance was reported for P<0.05.

Results

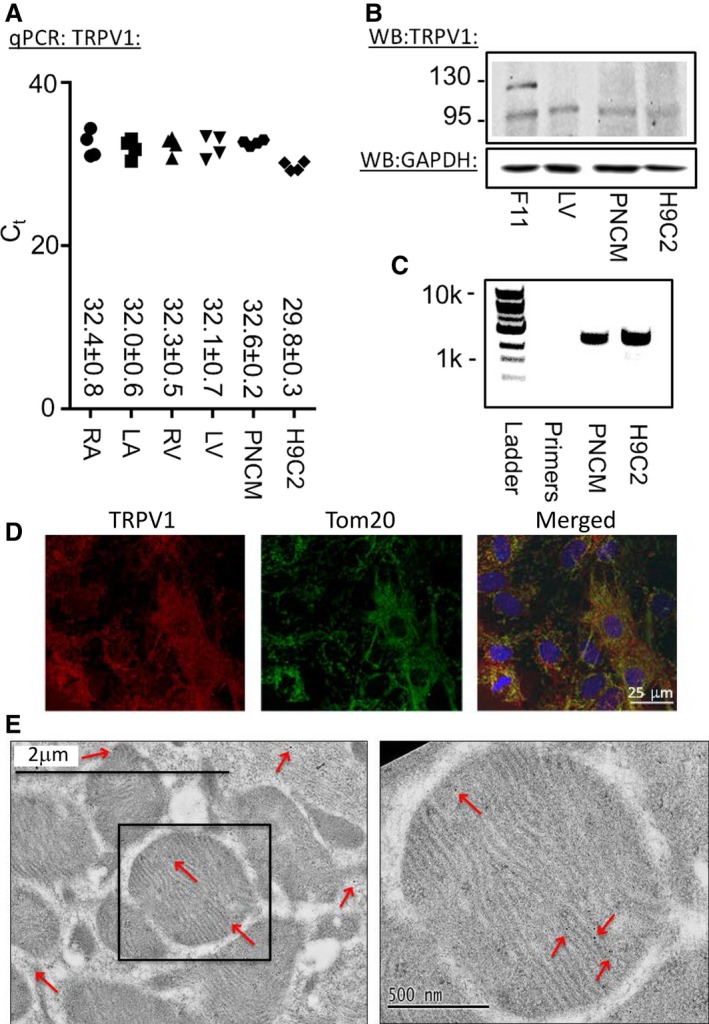

We initially tested whether TRPV1 was present in the cardiomyocyte. We detected TRPV1 by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and Western blot in heart homogenate, PNCMs, and the left ventricle–derived immortalized cell line H9C2 (Figure 1A and 1B, Figure S1A through S1C). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction detected TRPV1 in all 4 chambers of heart homogenate and in PNCMs and H9C2 cells but at low abundance (Figure 1A). Cycle threshold values corrected to GAPDH suggested that TRPV1 was more highly expressed in PNCMs and H9C2 cells compared with heart homogenates from all 4 heart chambers but did not reach statistical significance compared with left ventricle expression (Figure S1C). Western blot for homogenates implied that TRPV1 expression was mainly intracellular for cardiomyocytes because, compared with the neuronal cell line F11, minimal cell surface expression was noted. Surface expression of TRPV1 is associated with glycosylation that results in a 120‐kDa band rather than an intracellular 95‐kDa band (Figure 1B).19 Because TRPV1 splice variants are known to exist, we further performed reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. In PNCMs and H9C2 cells, a single band at the expected base pair length was present (Figure 1C). Sequencing of TRPV1 from PNCMs revealed a sequence similar to other previously documented noncardiac TRPV1 sequences (accession: NP_114188.1 and XP_008766014.1). In addition, no splice variants previously found in other cell lines derived from visceral organs were detected (Figure S1D).20 We further examined the localization of TRPV1 within the cell, and using confocal microscopy, we discovered that TRPV1 colocalized with the mitochondrial‐specific protein TOM20 (translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20) in PNCMs (Figure 1D). Wild‐type adult primary cardiomyocytes also stained positively for TRPV1 using immunofluorescence. The antibody used for TRPV1 failed to stain adult cardiomyocytes from a TRPV1 knockout rat (Figure S2). Furthermore, using electron microscopy with TRPV1 immunogold labeling, several gold particles were detected on or in the mitochondria per field, and >1 particle per mitochondria was found (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Biochemical evidence of TRPV1 is present in cardiomyocytes. A, qPCR for the 4 heart chambers (LV, LA, RV and RA), PNCMs, and the H9C2 cell line (n=4 biological replicates, each measured in triplicate). B, WB of total LV heart homogenate, PNCMs, and H9C2 cells. A dorsal root ganglion–derived cell line, F11, was used as a positive control. TRPV1 was intracellular (95 kDa) and glycosylated at the plasma membrane (120 kDa). GAPDH was used as a loading control (representative of 3 biological replicates). C, Reverse transcriptase PCR of PNCMs and H9C2 cells. D, Confocal imaging of TRPV1 in PNCMs with colocalization to TOM20, a specific mitochondrial membrane protein. E, Electron microscopy of mitochondria labeled for TRPV1 with immunogold particles (red arrows). LA indicates left atria; LV, left ventricle; PNCM, primary neonatal cardiomyocyte; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; RA, right atria; RV, right ventricle; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1; WB, Western blot.

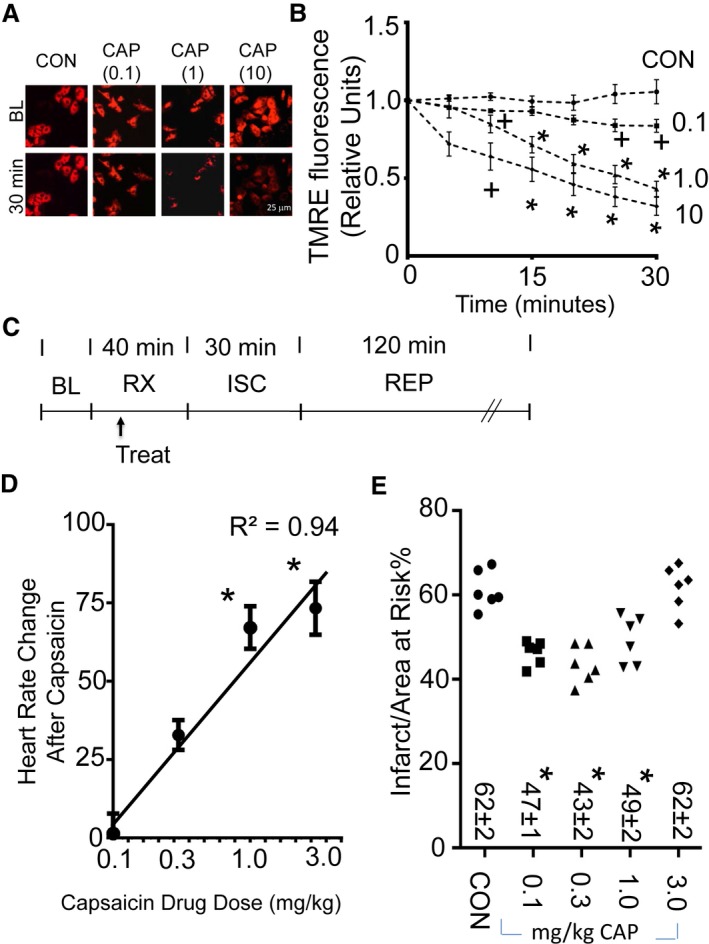

Because TRPV1 is at the mitochondria, we next determined whether TRPV1 functions at the mitochondria. We did so by measuring mitochondrial membrane potential after administration of the specific TRPV1 agonist capsaicin (range 0.1–10 μmol/L). Using PNCMs, capsaicin dose‐dependently decreased mitochondrial membrane potential assessed by cell imaging using TMRE (Figure 2A and 2B). Using a cell culture model of ischemia–reoxygenation, capsaicin reduced lactate dehydrogenase release at a low concentration (0.1 μmol/L), but this did not occur at higher capsaicin concentrations (1 and 10 μmol/L) (Figure S3A). For isolated unpaced rat hearts, unlike vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide), capsaicin increased heart rate during the first 15 minutes of infusion (Figure S3B and S3C). Because of the capsaicin‐dependent changes in heart rate, we used an in vivo left anterior descending coronary artery ligation model of ischemia–reperfusion injury and further tested how different capsaicin doses affected myocardial infarct size in vivo (experimental protocol shown in Figure 2C). After administration, capsaicin dose‐dependently increased heart rate when given intravenously (Figure 2D). The doses of capsaicin given also reduced myocardial infarct size in a narrow therapeutic window (0.1–1.0 mg/kg). A capsaicin dose of 3.0 mg/kg failed to reduce myocardial infarct size (Figure 2E). For groups tested, no differences were noted in the area at risk per left ventricle percentage (Figure S3D). Hemodynamics, including heart rate, blood pressure, and rate pressure product, were also assessed for these groups (Table 1).

Figure 2.

TRPV1 regulates mitochondrial membrane potential and infarct size. A, Representative images (at BL and 30 minutes after drug application) for assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential by TMRE for primary neonatal cardiomyocytes treated with vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide) or CAP (0.1, 1, or 10 μmol/L). B, TMRE fluorescence measurements (relative to each BL measurement set at 1) for vehicle or CAP (0.1, 1.0, or 10 μmol/L). CAP dose‐dependently caused changes in mitochondrial membrane potential over 30 minutes, as assessed by TMRE (3 biological replicates per group, + P<0.05 vs CON, *P<0.01 vs CON). C, Experimental protocol for myocardial ISC–REP studies. Arrow indicates time of treatment for either CON or CAP. D, Change in heart rate after CAP administration. CAP logarithmically increased heart rate in a dose‐dependent fashion (n=6 per group, *P<0.01). E, CAP maximally decreased infarct size at 0.3 mg/kg, with partial effects at 0.1 and 1.0 mg/kg. Individual infarct size for each experiment is presented (n=6 per group, *P<0.01 vs vehicle). BL indicates baseline; CAP, capsaicin; CON, control; ISC, ischemia; REP, reperfusion; RX, treatment; TMRE, tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1.

Table 1.

Hemodynamic Results for In Vivo Preconditioning Studies

| n | Baseline | Ischemia | Reperfusion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | MAP | RPP | HR | MAP | RPP | HR | MAP | RPP | ||

| Control | 6 | 345±6 | 127±4 | 51±2 | 352±4 | 109±4 | 44±2 | 350±8 | 92±3 | 38±1 |

| CAP (0.1) | 6 | 377±13 | 128±4 | 60±5 | 373±10 | 110±7 | 47±4 | 362±6 | 86±5 | 39±2 |

| CAP (0.3) | 6 | 370±11 | 137±7 | 60±5 | 360±21 | 89±14 | 40±7 | 368±6 | 85±3 | 38±2 |

| CAP (1.0) | 6 | 353±11 | 131±6 | 55±3 | 385±15 | 104±10 | 46±5 | 367±3 | 79±3 | 36±2 |

| CAP (3.0) | 6 | 357±8 | 127±4 | 53±2 | 420±9a | 113±5 | 53±3 | 370±4 | 72±4 | 35±2 |

| CPZ plus CAP | 6 | 370±11 | 134±4 | 58±3 | 385±10 | 106±11 | 46±4 | 383±16 | 74±3 | 37±1 |

| CsA plus CAP | 6 | 424±7a | 100±4 | 54±2 | 443±5a | 88±5 | 48±3 | 409±14a | 68±3 | 35±4 |

| CPZ | 5 | 366±7 | 129±6 | 56±3 | 356±14 | 108±12 | 45±5 | 356±7 | 89±3 | 39±2 |

| CsA | 6 | 410±11a | 106±5 | 54±4 | 433±10a | 89±4 | 48±2 | 399±14 | 78±3 | 40±3 |

Hemodynamic results for experimental groups measured at baseline, at 15 minutes of ischemia, and at 2 hours of reperfusion. No significant changes were noted between groups for each intervention phase. HR shown in beats per minute, MAP shown in mm Hg, RPP shown in mm Hg/1000. CAP indicates capsaicin; CPZ, capsazepine; CsA, cyclosporine; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; RPP, rate pressure product.

P<0.05 vs control.

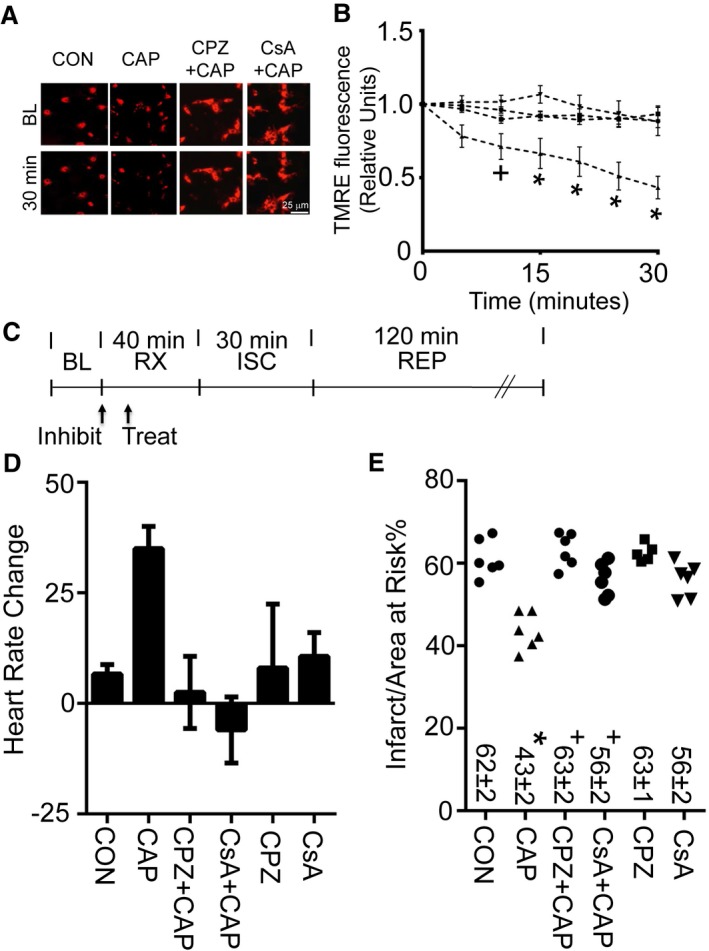

We next tested whether the capsaicin‐induced mitochondrial membrane potential changes and infarct size reduction were specific to TRPV1 and were calcineurin dependent. The changes in mitochondrial membrane potential induced by capsaicin were blocked by the TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine or the calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine (Figure 3A and 3B, Figure S4). We further tested whether capsazepine or cyclosporine blocked preconditioning‐induced infarct size reduction triggered by capsaicin in vivo (experimental protocol shown in Figure 3C). Both capsazepine and cyclosporine reduced the change in heart rate afforded by capsaicin administration at the 0.3‐mg/kg dose (Figure 3D). Furthermore, capsazepine or cyclosporine blocked the infarct size–sparing effect of capsaicin (Figure 3E). For the groups tested, no differences were noted in the percentage of area at risk per left ventricle (Figure S4C). Hemodynamics, including heart rate, blood pressure, and rate pressure product, were also assessed for these groups (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Calcineurin inhibition regulates mitochondrial membrane potential and infarct size. A, Representative images (at BL and 30 minutes after drug application) for assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential by TMRE for primary neonatal cardiomyocytes treated with CON (dimethyl sulfoxide) or CAP (1 μmol/L). A subset of groups was treated 10 minutes prior to CAP with CPZ (1 μmol/L) or CsA (1 μmol/L). B, TMRE fluorescence measurements for CON, CAP, CPZ plus CAP, or CsA plus CAP for 30 minutes, as assessed by TMRE (n=3 biological replicates per group, + P<0.05 or *P<0.01 for CON, CPZ plus CAP, or CsA plus CAP vs CAP). C, Experimental protocol for myocardial ISC–REP studies. “Treat” indicates time of treatment for either CON or CAP given 30 minutes prior to ISC. Arrow with “Inhibit” indicates time of treatment for either CPZ (3 mg/kg) or CsA (2.5 mg/kg) 40 minutes prior to ISC. D, Heart rate increase caused by CAP is blocked by either CPZ or CsA. E, Either CPZ or CsA blocks CAP‐induced infarct size reduction. For comparison purposes, both CON and CAP were replotted from Figure 2D and 2E for panels (D) and (E), respectively. *P<0.01 vs CON, + P<0.01 vs CAP alone. BL indicates baseline; CAP, capsaicin; CON, control; CPZ, capsazepine (3 mg/kg); CsA, cyclosporine (2.5 mg/kg); ISC, ischemia; REP, reperfusion; RX, treatment; TMRE, tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester.

Our findings suggested that capsaicin reduces myocardial injury with a narrow therapeutic window through a calcineurin‐dependent mechanism by altering mitochondrial membrane potential. With this in mind, we considered whether limiting, yet not completely blocking, TRPV1 channel gating could be an effective strategy to reduce myocardial reperfusion injury. To do so, we designed a short‐acting therapeutic that could limit the interaction of calcineurin with TRPV1 and tested whether we could reduce TRPV1‐induced changes in membrane potential within the mitochondria.

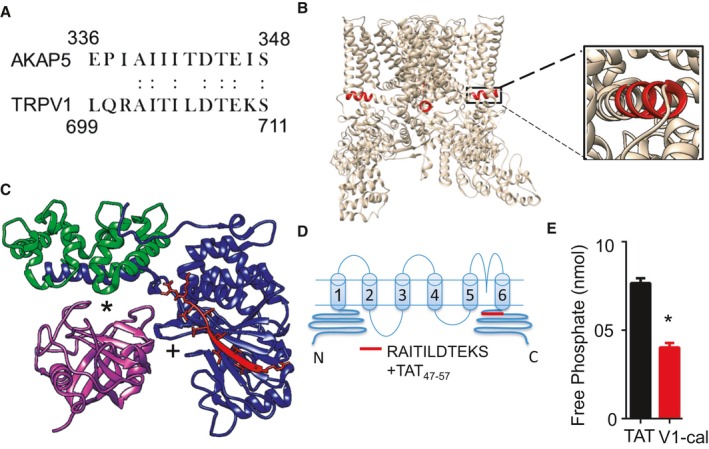

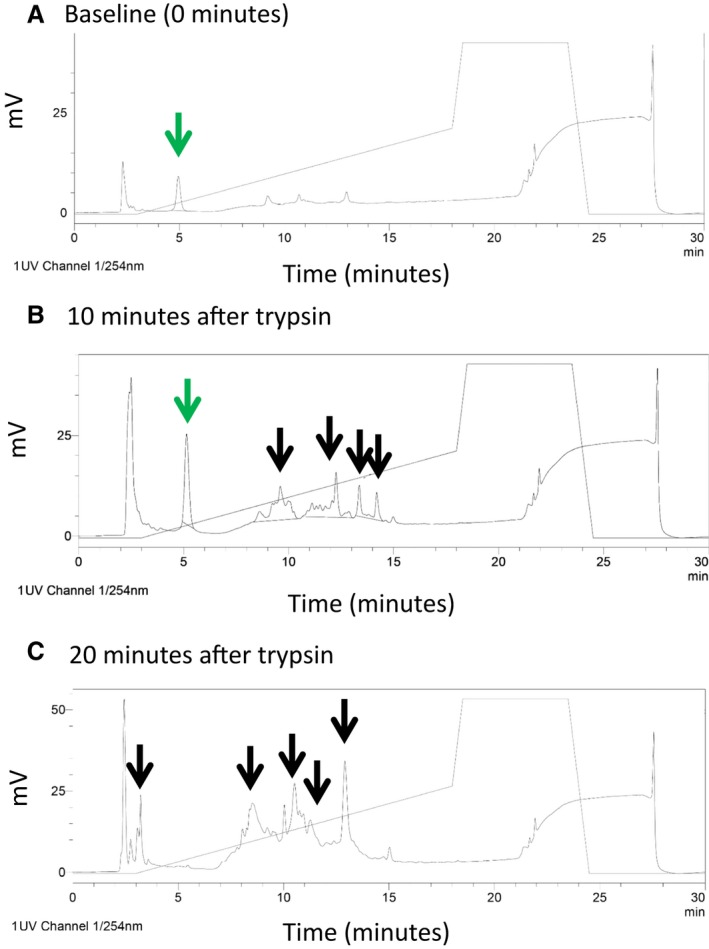

The A‐kinase anchoring protein 5 (AKAP5) sequence that interacts with calcineurin A was recently crystalized21; therefore, we determined whether a homologous interaction site for calcineurin A exists on TRPV1, using sequence homology with AKAP5. Using LALIGN,22 we found a sequence within the C terminus of TRPV1 that contained >50% sequence homology to the region of AKAP5 crystalized to the calcineurin A subunit (Figure 4A). A BLAST search using the input AIXIXDTEXS (X is a wild card in BLAST used to represent any amino acid) returned only sequences identified for either TRPV1 or AKAP5. The TRPV1 sequence was also in a C‐terminus region of TRPV1, forming an alpha coiled‐coil, which is part of the inner pore‐forming unit of the TRPV1 channel (Figure 4B).23 Furthermore, this region on TRPV1 was evolutionarily conserved in mammals (Figure S5A). We further modeled the TRPV1 region against the calcineurin A complex and cyclophilin D using PDB entries 3LL8 and 1AUI.21, 24 Unlike cyclosporine, which disrupts the interaction between cyclophilin D and the calcineurin B subunit, this TRPV1 region directly interacts with the calcineurin A subunit (Figure 4C). In particular, Thr704 of TRPV1 is in close proximity to Asn330, similar to how the Thr in the classical calcineurin inhibitor peptide PVIVIT interacts with calcineurin A at Asn330 (Figure S5B).25 Based on the region's sequence homology to AKAP5, evolutionary conservation, and location on the TRPV1 channel, we synthesized a peptide against this region and linked it to TAT47–57 for intracellular entry. We called the peptide V1‐cal (Figure 4D). We initially tested V1‐cal in a competitive in vitro calcineurin activity assay. In comparison to TAT, V1‐cal reduced the ability of calcineurin to dephosphorylate a calcineurin substrate, as measured by free phosphate release in vitro (Figure 4E). We also characterized the stability of the peptide when subjected to the peptidase trypsin over time. When V1‐cal was untreated with trypsin, a single peak at 5 minutes was detected by reverse‐phase high‐performance liquid chromatography (Figure 5A). After 20 minutes, the peptide was completely degraded (Figure 5B and 5C).

Figure 4.

The calcineurin A interaction site with TRPV1. A, The known interaction site of calcineurin A with AKAP5 has 54% sequence homology to a region on TRPV1 (homologous amino acid). B, This site on TRPV1, in red, forms a coiled‐coil region perpendicular to the pore‐forming unit of TRPV1. C, Predicted interaction site of V1‐cal with calcineurin A, based on the crystallization of the AKAP5 peptide with calcineurin A (3LL8). *Interaction site of complex with cyclosporine A. +Catalytic site for calcineurin A. D, Based on homology and structure, the V1‐cal peptide was synthesized against the alpha coiled‐coil TRPV1 region and linked to TAT for intracellular entry. E, In vitro kinase assay measuring calcineurin activity by free phosphate release (n=3 per group), *P<0.05. TAT indicates transactivator of transcription; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1.

Figure 5.

Determination of peptide stability. A, At baseline, a single peak at 5 minutes was noted when V1‐cal was analyzed by reverse‐phase high‐performance liquid chromatography (arrow in green). B, At 10 minutes after trypsin digestion, V1‐cal was still detected (arrow in green) but was 75% degraded, with multiple peaks detected as degradation products of V1‐cal (black arrows). C, At 20 minutes after exposure to trypsin, V1‐cal was 100% degraded (with no peak at 5 minutes and multiple other peaks detected, shown with black arrows).

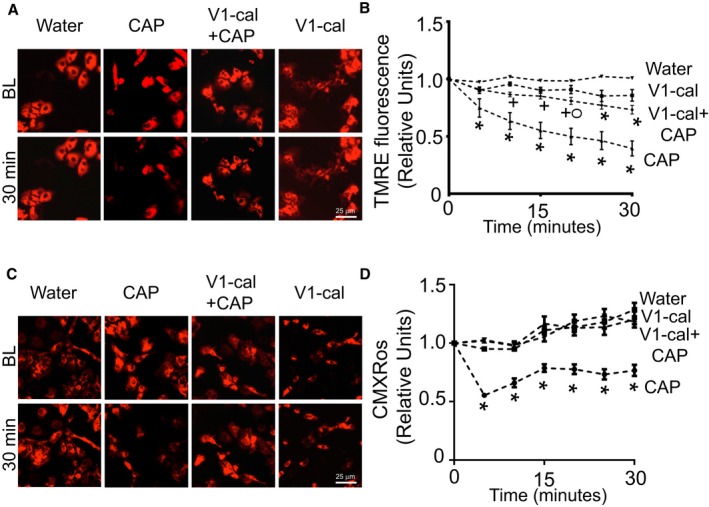

Because the interaction of calcineurin with TRPV1 is described as inducible,11 we treated PNCMs with V1‐cal (1 μmol/L) 10 minutes prior to capsaicin (1 μmol/L). The negative change in mitochondrial membrane potential caused by capsaicin, assessed by TMRE fluorescence, was reduced 10‐fold in the presence of V1‐cal (Figure 6A and 6B). Repeating these studies using the mitochondrial membrane potential indicator dye CMXRos also supported V1‐cal–reduced change in mitochondrial membrane potential caused by capsaicin (Figure 6C and 6D).

Figure 6.

V1‐cal abrogates TRPV1‐induced changes in mitochondrial membrane potential. A, Representative TMRE images of PNCMs at BL and after 30 minutes of treatment with water, CAP, V1‐cal plus CAP, or V1‐cal alone. B, Mitochondrial membrane potential assessed by TMRE for PNCMs treated with V1‐cal (1 μmol/L) prior to CAP (1 μmol/L; n=3 biological replicates per group). + P<0.01 vs CAP alone, O P<0.05 vs water, *P<0.01 vs water. C, Representative CMXRos images of PNCMs at baseline and after 30 minutes of treatment with water, CAP, V1‐cal plus CAP, or V1‐cal alone. D, Mitochondrial membrane potential assessed by CMXRos for PNCMs treated with V1‐cal (1 μmol/L) prior to CAP (1 μmol/L; n=3 biological replicates per group). *P<0.01 vs all other groups. BL indicates baseline; CAP, capsaicin; PNCM, primary neonatal cardiomyocyte; TMRE, tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1.

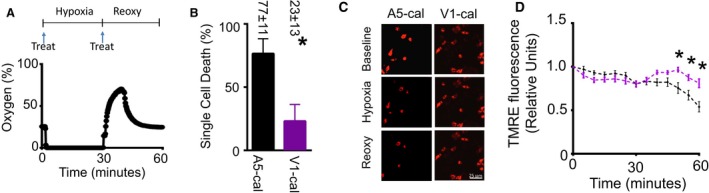

We next tested the effect of V1‐cal in a single‐cell model of hypoxia–reoxygenation. For comparison, we synthesized the sequence against AKAP5, AIIITILDTEIS (which corresponds to the TRPV1 sequence) (Figure 4A), linking the sequence to TAT47–57. We named this peptide A5‐cal, which was against the calcineurin interaction site to AKAP5. PNCMs were treated with either A5‐cal or V1‐cal just prior to 30‐minute hypoxia (<1% oxygen) and again prior to 30 minutes of reoxygenation (Figure 7A). V1‐cal, unlike A5‐cal, reduced the amount of cells that died after hypoxia–reoxygenation (Figure 7B). Of the cells that remained viable, V1‐cal, unlike A5‐cal, maintained mitochondrial membrane potential when cells were subjected to hypoxia–reoxygenation during assessment by either TMRE (Figure 7C and 7D) or CMXRos (Figure S6A and S6B).

Figure 7.

PNCM single‐cell hypoxia–Reoxy hypoxia‐reoxygenation studies. A, Cell hypoxia–reoxy experimental protocol. PNCMs were subjected to 30 minutes of hypoxia followed by 30 minutes of reperfusion. Cells were treated with A5‐cal (1 μmol/L) or V1‐cal (1 μmol/L) prior to hypoxia and prior Reoxy (arrow labeled “Treat”). During the protocol, oxygen levels were continuously monitored. B, V1‐cal significantly reduced the number of dead cells after hypoxia–Reoxy (n=3 biological replicates per group, *P<0.05). C, Representative TMRE images of PNCMs at baseline, after hypoxia, and after Reoxy with A5‐cal or V1‐cal. D, Mitochondrial membrane potential assessed by TMRE for PNCMs treated with A5‐cal or V1‐cal (n=3 biological replicates per group, *P<0.01 vs A5‐cal). PNCM indicates primary neonatal cardiomyocyte; reoxy, reoxygenation; TMRE, tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester.

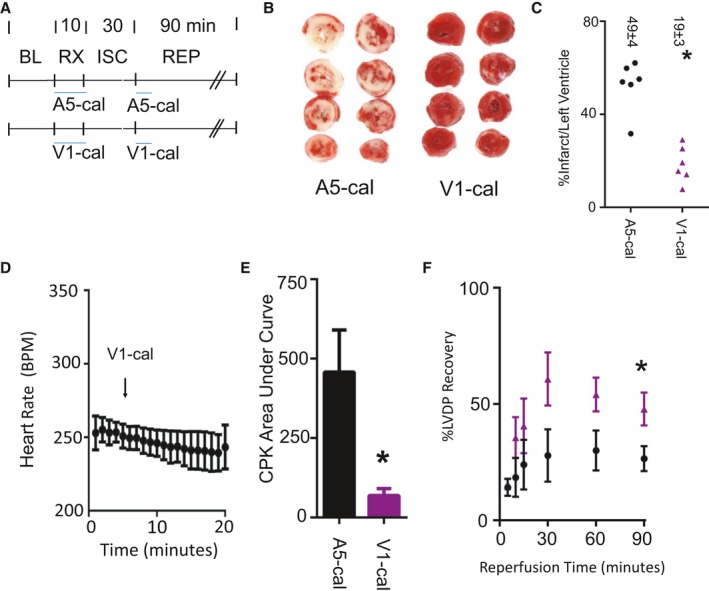

We tested the peptides in an isolated heart model of ischemia–reperfusion injury (devoid of nervous system input). Isolated hearts were perfused with either V1‐cal or A5‐cal for 10 minutes prior to ischemia and during the initial 3 minutes of reperfusion (experimental protocol is shown in Figure 8A). Most important, V1‐cal significantly reduced myocardial infarct size compared with A5‐cal (Figure 8B and 8C). Unlike capsaicin, V1‐cal did not have any effect on heart rate when infused (Figure 8D). Distinct from A5‐cal, V1‐cal reduced creatine phosphokinase release during the first 30 minutes of reperfusion (Figure 8E). Compared with A5‐cal, the recovery of left ventricular developed pressure was improved with V1‐cal (Figure 8F).

Figure 8.

Isolated heart myocardial infarction experiments. A, Isolated heart experimental protocol. Both V1‐cal and A5‐cal were given at doses of 1 μmol/L for 10 minutes prior to ISC and 3 minutes during REP. B, Representative infarct size images for 2 hearts per each group (n=6 per group, *P<0.01). C, Infarct size per left ventricle percentage for each group, with individual data points presented. D, Heart rate measured during the 10 minutes of administration for V1‐cal. E, CPK release during the first 30 minutes of REP. F, Percentage of LVDP (%LVDP) compared with BL. Data presented as mean±SEM (black, A5‐cal group; purple, V1‐cal group; n=6 per group). *P<0.05. BL indicates baseline; BPM, beats per minute; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; ISC, ischemia; LVDP, left ventricle developed pressure; REP, reperfusion; RX, treatment.

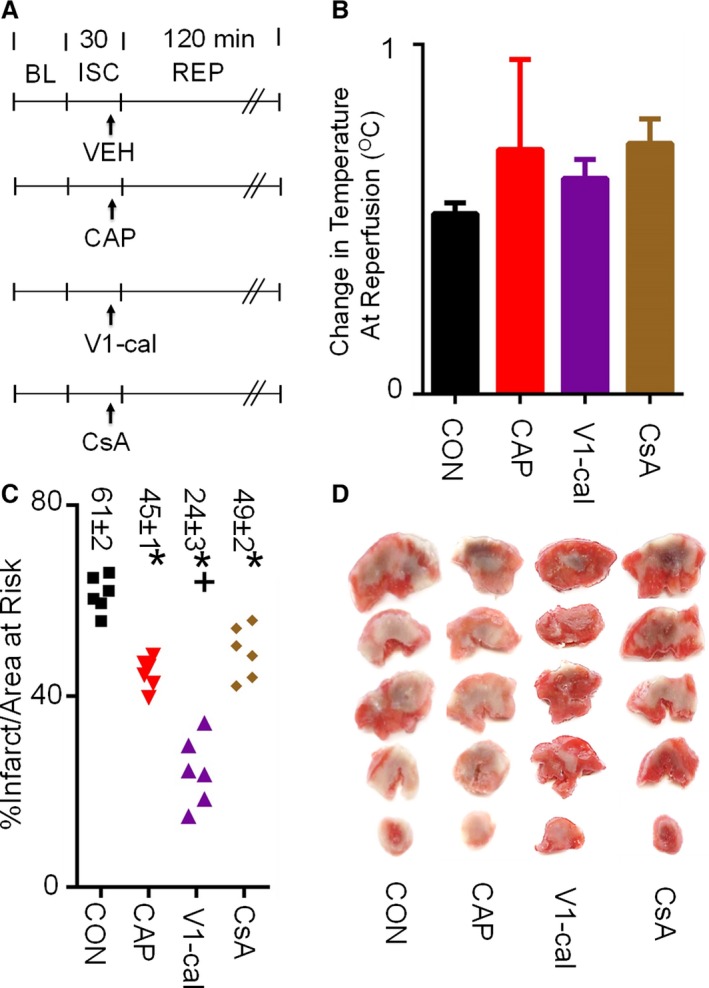

We tested whether V1‐cal compared with either capsaicin or cyclosporine could reduce myocardial infarct size as a single intravenous bolus just prior to reperfusion in an in vivo left anterior descending coronary artery ischemia–reperfusion injury model (experimental protocol shown in Figure 9A). Because a prior report suggested that capsaicin reduces myocardial infarct size by producing hypothermia,26 we measured rectal body temperature for each group (Table 2). None of the agents administered compared with control changed thermoregulation for the rodent model used, which involved warming with heating lamps and using a heated table (Figure 9B). V1‐cal significantly reduced myocardial infarct size by 61% compared with control versus the 27% and 20% infarct size reduction by capsaicin or cyclosporine, respectively, when given 5 minutes before reperfusion (Figure 9C and 9D). No differences were noted in area at risk per left ventricle percentage (Figure S7A). Hemodynamics, including heart rate, blood pressure, and rate pressure product, were also assessed for these groups (Table 2).

Figure 9.

In vivo myocardial infarction experiments. A, Experimental protocol. All agents were given 5 minutes prior to REP (CAP 0.3 mg/kg, CsA 2.5 mg/kg, V1‐cal 1 mg/kg). B, Temperature difference at REP relative to BL measurements for each group. C, Infarct size per area at risk as a percentage. D, Representative images of left ventricle area at risk for each group (n=6 per group, *P<0.01 vs CON, + P<0.01 vs all groups). BL indicates baseline; CAP, capsaicin; CON, control; CsA, cyclosporine; ISC, ischemia; REP, reperfusion; VEH, vehicle.

Table 2.

Hemodynamic Results for In Vivo Reperfusion Studies

| n | Baseline | Ischemia | Reperfusion | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | MAP | RPP | TEMP | HR | MAP | RPP | TEMP | HR | MAP | RPP | TEMP | ||

| Control | 6 | 371±10 | 118±7 | 48±3 | 36.6±0.2 | 385±11 | 103±12 | 43±5 | 36.9±0.2 | 378±16 | 92±6 | 39±3 | 37.1±0.2 |

| CAP | 6 | 370±6 | 134±3 | 58±2 | 36.8±0.2 | 377±11 | 118±10 | 51±5 | 37.7±1.3 | 363±9 | 87±7 | 39±3 | 37.5±0.1 |

| V1‐cal | 6 | 428±6 | 115±5 | 49±3 | 36.6±0.5 | 432±10 | 110±5 | 47±3 | 36.6±0.1 | 400±8 | 85±4 | 34±2 | 37.2±0.1 |

| CsA | 6 | 413±14 | 99±6 | 36±8 | 36.6±0.2 | 398±16 | 75±6 | 30±3 | 36.5±0.1 | 389±15 | 68±5 | 26±3 | 37.2±0.1 |

| TRPV1 (−/−) | 6 | 423±14 | 122±5 | 62±4 | 36.9±0.1 | 430±12 | 104±10 | 52±5 | 37.1±0.1 | 392±7 | 82±7 | 43±4 | 37.3±0.2 |

| V1‐cal plus TRPV1 (−/−) | 6 | 439±12a | 123±6 | 61±4 | 36.9±0.2 | 446±13 | 114±7 | 56±4 | 37.1±0.1 | 391±15 | 84±8 | 40±4 | 37.0±0.1 |

Hemodynamic results for experimental groups measured at baseline, at 15 minutes of ischemia, and at 2 hours of reperfusion. HR shown in beats per minute, MAP shown in mm Hg, RPP shown in mm Hg/1000. CAP indicates capsaicin; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; RPP, rate pressure product; TEMP, rectal body temperature; TRPV1 (−/−), TRPV1 knockout rat.

P<0.05 vs control.

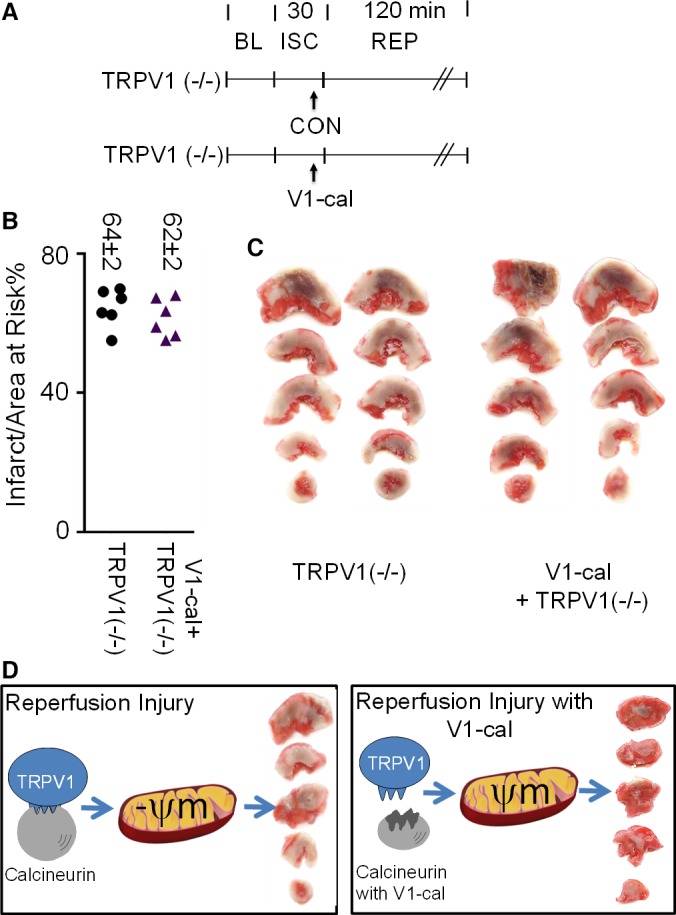

To confirm selectivity of V1‐cal, we further administered V1‐cal to male Sprague‐Dawley TRPV1 knockout rats (experimental protocol shown in Figure 10A). These TRPV1 knockout rodents displayed no differences in baseline hemodynamics such as blood pressure and rate pressure product or baseline rectal temperature (Table 2). Compared with wild‐type Sprague‐Dawley rats, the infarct size–sparing effect of V1‐cal was completely abrogated and without effect compared with TRPV1 knockout rat controls (Figure 10B and 10C). For groups tested, no differences were noted in the percentage of area at risk per left ventricle (Figure S7B).

Figure 10.

V1‐cal selectively targets TRPV1. A, Experimental protocol for knockout TRPV1 rats (TRPV1 [−/−]). B, Infarct size per area at risk as a percentage for TRPV1 knockout rats. C, Representative images of 2 hearts for each experiment. D, Summary figure: V1‐cal acts as an inhibitor for calcineurin interacting with TRPV1 when TRPV1 is activated by cellular stress. This limits changes in mitochondrial membrane potential and mitigates cardiac reperfusion injury. Mitochondria image adapted from Small et al.27 BL indicates baseline; CON, control; ISC, ischemia; REP, reperfusion; ψm, mitochondrial membrane potential; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1.

Discussion

In this study, we described how TRPV1 is localized at the mitochondria and regulates mitochondrial membrane potential and reperfusion injury. Creating a peptide, V1‐cal, to inhibit the interaction of calcineurin with TRPV1 reduced myocardial infarct size in both isolated heart and in vivo myocardial infarct models. The effect seen with V1‐cal is far superior to capsaicin or cyclosporine. The 61% infarct size reduction is also substantial compared with our prior studies using this in vivo myocardial infarction model with single‐dose intravenous agents given prior to reperfusion.12, 17

Our data suggest that TRPV1 is a low‐abundance cardiomyocyte protein that is intracellular. The interaction of calcineurin with TRPV1 is inducible.11 This calcineurin interaction site located after the C‐terminus TRP box is part of the inner pore‐forming unit of TRPV1.9 These qualities of the interaction—TRPV1 being a low‐abundance protein, conservation across mammalian species, and the interaction of calcineurin with TRPV1 being inducible—allowed us to target TRPV1 using a peptide that we designed, V1‐cal, by mimicking the calcineurin interaction site on TRPV1. Because unmodified peptides from natural amino acid sequences have short half‐lives and the peptide we designed is degraded by trypsin within 20 minutes, the effect of V1‐cal occurs only during the initial minutes of reperfusion.28 This short time frame of inhibition is important because TRPV1 and other TRP channel family members contribute to myocardial remodeling after reperfusion injury.29, 30

Indirectly modulating the TRPV1 channel may solve problems of drug development for TRPV1. Our indirect approach of modifying a protein interacting with TRPV1 had little noticeable effect on temperature and heart rate. This is important because prior attempts to design an antagonist of the TRPV1 channel, such as AMG517, caused sudden hyperthermia in humans that persisted for days.31 Furthermore, TRPV1 antagonists block the natural endogenous pathways of cardioprotection including pre‐ and postconditioning.32 In contrast, specific TRPV1 agonists are painful. As shown by this study, capsaicin has a small therapeutic window for cardioprotection that increases heart rate. Even a small change in heart rate may be detrimental if a person is having an acute myocardial infarction. Case reports also suggest that excessive consumption of cayenne pepper (the active component of which is capsaicin) can result in myocardial infarction due to coronary vasospasm.33, 34 Consequently, direct agonists and antagonists of the TRPV1 channel have substantial disadvantages over indirect modulation, as described with V1‐cal.

TRPV1 exists in an open, closed, or inactive state. On activation and calcium influx, TRPV1 gating status is regulated by a phosphorylation balance mediated by calmodulin and calcineurin,35 similar to other ion channels such as Kir2.1.36 When calmodulin is overexpressed, the TRPV1 gating response is significantly diminished.37 Also after TRPV1 stimulation, calmodulin switches the channel state from active to inactive, holding the TRPV1 channel in a closed state.38 Calcineurin alternatively dephosphorylates the TRPV1 channel after activation, priming the channel for reactivation. The peptide V1‐cal limits calcineurin interaction with TRPV1, changing the balance of calcineurin and calmodulin. Calmodulin phosphorylation is unopposed when calcineurin dephosphorylation is limited. This keeps the TRPV1 channel in an inactive state during the initial minutes of reperfusion, mitigating changes in mitochondrial membrane potential.

In addition to capsaicin, previously known endogenous activators of TRPV1, including 12‐hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid and 2‐arachindonyl, have myocardial salvage properties.39, 40 Exogenous TRPV1 agonists, including bradykinin, adenosine, ethanol, and volatile anesthetics,41, 42 also exhibit myocardial salvage properties.43, 44 Cyclosporine blocked capsaicin‐induced preconditioning when given prior to ischemia, similar to how cyclosporine blocks ischemic before conditioning.45 Moreover, the effect seen for TRPV1 activation is likely independent of hypothermia, as suggested previously,26 because our study noted no hypothermic effects from direct or indirect TRPV1 agonists or antagonists administered. Together, these findings suggest that the TRPV1 channel is a plausible end‐effector and mediator of myocardial salvage and perhaps even a common end‐effector for many of the ligands that mediate cardioprotection.

TRPV1 has unique gating qualities for which increasing oxygen saturation triggers calcium‐induced influx through TRP channels, including TRPV1.6 In addition, TRPV1 allows passage of larger cations and molecules through the TRPV1 pore. Molecules including FM1‐43,46 QX314,47 and spermine,48 with the molecule FM1‐43 having a 452‐Da molecular mass, are gated through TRPV1. Because TRPV1 may be activated by many factors during reperfusion, including endogenous metabolites, oxygen, and pH, shifting the TRPV1 channel to a more closed state during the initial minutes of reperfusion limits the ability of calcium to overload into the mitochondria and cations and molecules through the channel.

When controlled for temperature, pH, and oxygen saturation, our data indicated that TRPV1 regulates mitochondrial membrane potential. We found in cardiomyocytes that TRPV1 has an estimated molecular weight of ≈95 kDa, which is consistent with Western blot analysis reported previously in myocardial tissue.49 When present at the cell surface, the protein is glycosylated at Asn604, resulting in a shift in molecular weight to ≈110 kDa.19 We found that the TRPV1 channel in cardiomyocytes is minimally expressed on the cell surface through both Western blot and immunofluorescence, suggesting the concept that most TRPV1 signaling in the cardiomyocyte is intracellular. In addition, the gene product we sequenced from the cardiomyocyte is the same as that found in dorsal root ganglion for TRPV1, and we did not find any splice variants. Splice variants for TRPV1 exist in other organs20 and cell lines50 and contribute in an inhibitory role to reducing or blocking the activity for the full‐length TRPV1 channel.

To our knowledge, this report is the first published using a TRPV1 knockout rat. The primary purpose of using the TRPV1 knockout rodent for these studies was to validate our selectivity of the V1‐cal peptide we designed. For this reason, we verified that the gene was knocked out in the cardiomyocyte (Figure S2) in addition to obtaining baseline hemodynamic variables in these rodents. V1‐cal is ineffective in reducing myocardial injury for the TRPV1 knockout rat, and further studies will be needed to fully characterize the TRPV1 knockout rat to determine whether it is resistant to ischemic preconditioning and ischemic postconditioning, as was previously shown for the knockout TRPV1 mouse.29, 32

Our data suggest that cyclosporine reduces myocardial infarct size in rats but may do so by indirectly modulating the calcineurin–TRPV1 interaction (Figure 5C). Finding that TRPV1 is present at the mitochondria and designing a targeted therapeutic against the interaction of calcineurin with TRPV1, as we did in this study, may provide clues as to how to better limit reperfusion injury in humans during percutaneous coronary intervention or cardiac bypass surgery.

Conclusions

We described a unique role for TRPV1 in the cardiomyocyte, to regulate mitochondrial membrane potential, and a new therapeutic, V1‐cal, that specifically targets the TRPV1 protein–protein interaction with calcineurin to reduce reperfusion injury (Figure 10D26). Our study suggested that TRPV1 is present in the cardiomyocyte and functions to regulate mitochondrial membrane potential. Shifting the TRPV1 channel to a more closed state substantially mitigates reperfusion injury. These findings suggest that the peptide V1‐cal can limit changes in mitochondrial membrane potential. V1‐cal could be useful for maintaining mitochondrial integrity during states of cellular stress, particularly during myocardial infarction or cardiac bypass surgery.

Sources of Funding

Support for this work was provided by NIH HL‐109212 (E.R. Gross), AHA FTF19970029 (Stary), HL‐74314 (Mochly‐Rosen), HL‐109212‐03S1 (E.R. Gross) and HL‐052141 (G.J. Gross). The confocal microscope work in this project was partially supported by Award Number 1S10OD010580 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR).

Disclosures

A preliminary patent was filed regarding peptides modulators to break specific calcineurin protein interactions.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supplemental methods.

Table S1. Total Number of Rodents Used for the Study, Including Those Included and Excluded and Reasons for Exclusion

Figure S1. A, Representative TRPV1 DNA gel for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) experiments. B, Representative TRPV1 melt curve for qPCR experiments. C, ΔCt relative to GAPDH for heart homogenate of different heart chambers and cells tested. D, Sequence of TRPV1 in rat primary neonatal cardiomyocytes. Underlined portions are regions sequenced prior to and after the TRPV1 start and end sequence.

Figure S2. A, TRPV1 colocalizes with TOM20 in primary adult cardiomyocytes. B, Knockout verification of the antibody for selectivity. In addition this also validates the rodent model purchased also had TRPV1 knocked out in primary cardiomyocytes.

Figure S3. A, Cell ischemia–reoxygenation experiments with H9C2 cells. Capsaicin reduced lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release only at a lower dose (0.1 μmol/L) compared with higher doses of capsaicin (1 and 10 μmol/L; n=8 per group). *P<0.01, + P<0.05 vs control. Percentage of LDH release noted as mean±SEM. B and C, In isolated hearts after capsaicin administration, capsaicin (0.1 μmol/L) increased heart rate unlike vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide). + P<0.05 vs prior to administration (n=4 per group). D, Area at risk per left ventricle percentage for each group.

Figure S4. A, Representative images of primary neonatal cardiomyocytes (PNCMs) at time 0 and after 30 minutes of treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) alone, CPZ plus DMSO, and cyclosporine (CsA) plus DMSO groups. B, Graph of data collected for groups including DMSO alone (triangle), CPZ plus DMSO (square), and CsA plus DMSO (diamond) (n=3 biological replicates per group). C, Area at risk per left ventricle for each individual group.

Figure S5. A, The TRPV1 region in which V1‐cal was constructed is strongly conserved in mammals. B, Structure showing Thr704 of TRPV1 is near the Asn330 site of calcineurin A.

Figure S6. Single‐cell and isolated heart experiments A, Representative CMXRos images of primary neonatal cardiomyocytes (PNCMs) at time 0 and after hypoxia–reoxygenation with A5‐cal (black) or V1‐cal (purple). B, Mitochondrial membrane potential assessed by CMXRos for PNCMs treated with A5‐cal (1 mmol/L) or V1‐cal (1 mmol/L; n=3 biological replicates per group, *P<0.01 vs A5‐cal).

Figure S7. In vivo experiments. A, Area at risk per left ventricle for each group. B, Area at risk per left ventricle for each group.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Marie‐Helene Disatnik for teaching the lab the primary neonatal cardiomyocyte isolation method.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003774 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003774)

References

- 1. Hausenloy D, Kunst G, Boston‐Griffiths E, Kolvekar S, Chaubey S, John L, Desai J, Yellon D. The effect of cyclosporin‐A on peri‐operative myocardial injury in adult patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Heart. 2014;100:544–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Piot C, Croisille P, Staat P, Thibault H, Rioufol G, Mewton N, Elbelghiti R, Cung TT, Bonnefoy E, Angoulvant D, Macia C, Raczka F, Sportouch C, Gahide G, Finet G, Andre‐Fouet X, Revel D, Kirkorian G, Monassier JP, Derumeaux G, Ovize M. Effect of cyclosporine on reperfusion injury in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chiari P, Angoulvant D, Mewton N, Desebbe O, Obadia JF, Robin J, Farhat F, Jegaden O, Bastien O, Lehot JJ, Ovize M. Cyclosporine protects the heart during aortic valve surgery. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cung TT, Morel O, Cayla G, Rioufol G, Garcia‐Dorado D, Angoulvant D, Bonnefoy‐Cudraz E, Guerin P, Elbaz M, Delarche N, Coste P, Vanzetto G, Metge M, Aupetit JF, Jouve B, Motreff P, Tron C, Labeque JN, Steg PG, Cottin Y, Range G, Clerc J, Claeys MJ, Coussement P, Prunier F, Moulin F, Roth O, Belle L, Dubois P, Barragan P, Gilard M, Piot C, Colin P, De Poli F, Morice MC, Ider O, Dubois‐Rande JL, Unterseeh T, Le Breton H, Beard T, Blanchard D, Grollier G, Malquarti V, Staat P, Sudre A, Elmer E, Hansson MJ, Bergerot C, Boussaha I, Jossan C, Derumeaux G, Mewton N, Ovize M. Cyclosporine before PCI in patients with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1021–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1121–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Takahashi N, Kuwaki T, Kiyonaka S, Numata T, Kozai D, Mizuno Y, Yamamoto S, Naito S, Knevels E, Carmeliet P, Oga T, Kaneko S, Suga S, Nokami T, Yoshida J, Mori Y. TRPA1 underlies a sensing mechanism for O2. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:701–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sexton A, McDonald M, Cayla C, Thiemermann C, Ahluwalia A. 12‐Lipoxygenase‐derived eicosanoids protect against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via activation of neuronal TRPV1. FASEB J. 2007;21:2695–2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat‐activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cao E, Liao M, Cheng Y, Julius D. TRPV1 structures in distinct conformations reveal activation mechanisms. Nature. 2013;504:113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jung J, Hwang SW, Kwak J, Lee SY, Kang CJ, Kim WB, Kim D, Oh U. Capsaicin binds to the intracellular domain of the capsaicin‐activated ion channel. J Neurosci. 1999;19:529–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Por ED, Samelson BK, Belugin S, Akopian AN, Scott JD, Jeske NA. PP2B/calcineurin‐mediated desensitization of TRPV1 does not require AKAP150. Biochem J. 2010;432:549–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gross ER, Hsu AK, Urban TJ, Mochly‐Rosen D, Gross GJ. Nociceptive‐induced myocardial remote conditioning is mediated by neuronal gamma protein kinase C. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Disatnik MH, Ferreira JC, Campos JC, Gomes KS, Dourado PM, Qi X, Mochly‐Rosen D. Acute inhibition of excessive mitochondrial fission after myocardial infarction prevents long‐term cardiac dysfunction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000461 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patel HH, Head BP, Petersen HN, Niesman IR, Huang D, Gross GJ, Insel PA, Roth DM. Protection of adult rat cardiac myocytes from ischemic cell death: role of caveolar microdomains and delta‐opioid receptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H344–H350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Papanicolaou KN, Khairallah RJ, Ngoh GA, Chikando A, Luptak I, O'Shea KM, Riley DD, Lugus JJ, Colucci WS, Lederer WJ, Stanley WC, Walsh K. Mitofusin‐2 maintains mitochondrial structure and contributes to stress‐induced permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1309–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yogalingam G, Hwang S, Ferreira JC, Mochly‐Rosen D. Glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) phosphorylation by protein kinase cdelta (PKCδ) inhibits mitochondria elimination by lysosomal‐like structures following ischemia and reoxygenation‐induced injury. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:18947–18960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gross ER, Hsu AK, Gross GJ. Opioid‐induced cardioprotection occurs via glycogen synthase kinase beta inhibition during reperfusion in intact rat hearts. Circ Res. 2004;94:960–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gross ER, Hsu AK, Gross GJ. Acute methadone treatment reduces myocardial infarct size via the delta‐opioid receptor in rats during reperfusion. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1395–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jahnel R, Dreger M, Gillen C, Bender O, Kurreck J, Hucho F. Biochemical characterization of the vanilloid receptor 1 expressed in a dorsal root ganglia derived cell line. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:5489–5496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tian W, Fu Y, Wang DH, Cohen DM. Regulation of TRPV1 by a novel renally expressed rat TRPV1 splice variant. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F117–F126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li H, Pink MD, Murphy JG, Stein A, Dell'Acqua ML, Hogan PG. Balanced interactions of calcineurin with AKAP79 regulate Ca2+‐calcineurin‐NFAT signaling. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang X, Miller W. A time‐efficient, linear‐space local similarity algorithm. Adv Appl Math. 1991;12:337–357. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liao M, Cao E, Julius D, Cheng Y. Structure of the TRPV1 ion channel determined by electron cryo‐microscopy. Nature. 2013;504:107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jin L, Harrison SC. Crystal structure of human calcineurin complexed with cyclosporin A and human cyclophilin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13522–13526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li H, Zhang L, Rao A, Harrison SC, Hogan PG. Structure of calcineurin in complex with PVIVIT peptide: portrait of a low‐affinity signalling interaction. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:1296–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dow J, Simkhovich BZ, Hale SL, Kay G, Kloner RA. Capsaicin‐induced cardioprotection. Is hypothermia or the salvage kinase pathway involved? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2014;28:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Small BA, Lu Y, Hsu AK, Gross GJ, Gross ER. Morphine reduces myocardial infarct size via heat shock protein 90 in rodents. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:129612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Inagaki K, Begley R, Ikeno F, Mochly‐Rosen D. Cardioprotection by epsilon‐protein kinase C activation from ischemia: continuous delivery and antiarrhythmic effect of an epsilon‐protein kinase C‐activating peptide. Circulation. 2005;111:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang W, Rubinstein J, Prieto AR, Thang LV, Wang DH. Transient receptor potential vanilloid gene deletion exacerbates inflammation and atypical cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. Hypertension. 2009;53:243–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Makarewich CA, Zhang H, Davis J, Correll RN, Trappanese DM, Hoffman NE, Troupes CD, Berretta RM, Kubo H, Madesh M, Chen X, Gao E, Molkentin JD, Houser SR. Transient receptor potential channels contribute to pathological structural and functional remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2014;115:567–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gavva NR, Treanor JJ, Garami A, Fang L, Surapaneni S, Akrami A, Alvarez F, Bak A, Darling M, Gore A, Jang GR, Kesslak JP, Ni L, Norman MH, Palluconi G, Rose MJ, Salfi M, Tan E, Romanovsky AA, Banfield C, Davar G. Pharmacological blockade of the vanilloid receptor TRPV1 elicits marked hyperthermia in humans. Pain. 2008;136:202–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhong B, Wang DH. TRPV1 gene knockout impairs preconditioning protection against myocardial injury in isolated perfused hearts in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1791–H1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sogut O, Kaya H, Gokdemir MT, Sezen Y. Acute myocardial infarction and coronary vasospasm associated with the ingestion of cayenne pepper pills in a 25‐year‐old male. Int J Emerg Med. 2012;5:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sayin MR, Karabag T, Dogan SM, Akpinar I, Aydin M. A case of acute myocardial infarction due to the use of cayenne pepper pills. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124:285–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jung J, Shin JS, Lee SY, Hwang SW, Koo J, Cho H, Oh U. Phosphorylation of vanilloid receptor 1 by Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent kinase II regulates its vanilloid binding. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7048–7054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kubokawa M, Kojo T, Komagiri Y, Nakamura K. Role of calcineurin‐mediated dephosphorylation in modulation of an inwardly rectifying K+ channel in human proximal tubule cells. J Membr Biol. 2009;231:79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rosenbaum T, Gordon‐Shaag A, Munari M, Gordon SE. Ca2+/calmodulin modulates TRPV1 activation by capsaicin. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hucho T, Suckow V, Joseph EK, Kuhn J, Schmoranzer J, Dina OA, Chen X, Karst M, Bernateck M, Levine JD, Ropers HH. Ca++/CAMKII switches nociceptor‐sensitizing stimuli into desensitizing stimuli. J Neurochem. 2012;123:589–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gross ER, Hsu AK, Gross GJ. Acute aspirin treatment abolishes, whereas acute ibuprofen treatment enhances morphine‐induced cardioprotection: role of 12‐lipoxygenase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wagner JA, Abesser M, Harvey‐White J, Ertl G. 2‐Arachidonylglycerol acting on CB1 cannabinoid receptors mediates delayed cardioprotection induced by nitric oxide in rat isolated hearts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;47:650–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cornett PM, Matta JA, Ahern GP. General anesthetics sensitize the capsaicin receptor transient receptor potential V1. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1261–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Trevisani M, Smart D, Gunthorpe MJ, Tognetto M, Barbieri M, Campi B, Amadesi S, Gray J, Jerman JC, Brough SJ, Owen D, Smith GD, Randall AD, Harrison S, Bianchi A, Davis JB, Geppetti P. Ethanol elicits and potentiates nociceptor responses via the vanilloid receptor‐1. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:546–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen CH, Gray MO, Mochly‐Rosen D. Cardioprotection from ischemia by a brief exposure to physiological levels of ethanol: role of epsilon protein kinase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12784–12789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kersten JR, Schmeling TJ, Pagel PS, Gross GJ, Warltier DC. Isoflurane mimics ischemic preconditioning via activation of K(ATP) channels: reduction of myocardial infarct size with an acute memory phase. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hausenloy D, Wynne A, Duchen M, Yellon D. Transient mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening mediates preconditioning‐induced protection. Circulation. 2004;109:1714–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Meyers JR, MacDonald RB, Duggan A, Lenzi D, Standaert DG, Corwin JT, Corey DP. Lighting up the senses: FM1‐43 loading of sensory cells through nonselective ion channels. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4054–4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Binshtok AM, Bean BP, Woolf CJ. Inhibition of nociceptors by TRPV1‐mediated entry of impermeant sodium channel blockers. Nature. 2007;449:607–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ahern GP, Wang X, Miyares RL. Polyamines are potent ligands for the capsaicin receptor TRPV1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8991–8995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Song JX, Wang LH, Yao L, Xu C, Wei ZH, Zheng LR. Impaired transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 in streptozotocin‐induced diabetic hearts. Int J Cardiol. 2009;134:290–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vos MH, Neelands TR, McDonald HA, Choi W, Kroeger PE, Puttfarcken PS, Faltynek CR, Moreland RB, Han P. TRPV1B overexpression negatively regulates TRPV1 responsiveness to capsaicin, heat and low pH in HEK293 cells. J Neurochem. 2006;99:1088–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supplemental methods.

Table S1. Total Number of Rodents Used for the Study, Including Those Included and Excluded and Reasons for Exclusion

Figure S1. A, Representative TRPV1 DNA gel for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) experiments. B, Representative TRPV1 melt curve for qPCR experiments. C, ΔCt relative to GAPDH for heart homogenate of different heart chambers and cells tested. D, Sequence of TRPV1 in rat primary neonatal cardiomyocytes. Underlined portions are regions sequenced prior to and after the TRPV1 start and end sequence.

Figure S2. A, TRPV1 colocalizes with TOM20 in primary adult cardiomyocytes. B, Knockout verification of the antibody for selectivity. In addition this also validates the rodent model purchased also had TRPV1 knocked out in primary cardiomyocytes.

Figure S3. A, Cell ischemia–reoxygenation experiments with H9C2 cells. Capsaicin reduced lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release only at a lower dose (0.1 μmol/L) compared with higher doses of capsaicin (1 and 10 μmol/L; n=8 per group). *P<0.01, + P<0.05 vs control. Percentage of LDH release noted as mean±SEM. B and C, In isolated hearts after capsaicin administration, capsaicin (0.1 μmol/L) increased heart rate unlike vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide). + P<0.05 vs prior to administration (n=4 per group). D, Area at risk per left ventricle percentage for each group.

Figure S4. A, Representative images of primary neonatal cardiomyocytes (PNCMs) at time 0 and after 30 minutes of treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) alone, CPZ plus DMSO, and cyclosporine (CsA) plus DMSO groups. B, Graph of data collected for groups including DMSO alone (triangle), CPZ plus DMSO (square), and CsA plus DMSO (diamond) (n=3 biological replicates per group). C, Area at risk per left ventricle for each individual group.

Figure S5. A, The TRPV1 region in which V1‐cal was constructed is strongly conserved in mammals. B, Structure showing Thr704 of TRPV1 is near the Asn330 site of calcineurin A.

Figure S6. Single‐cell and isolated heart experiments A, Representative CMXRos images of primary neonatal cardiomyocytes (PNCMs) at time 0 and after hypoxia–reoxygenation with A5‐cal (black) or V1‐cal (purple). B, Mitochondrial membrane potential assessed by CMXRos for PNCMs treated with A5‐cal (1 mmol/L) or V1‐cal (1 mmol/L; n=3 biological replicates per group, *P<0.01 vs A5‐cal).

Figure S7. In vivo experiments. A, Area at risk per left ventricle for each group. B, Area at risk per left ventricle for each group.