Abstract

Background

Recent trials have demonstrated that extended cardiac monitoring increases the yield of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) detection in patients with cryptogenic stroke. The utility of extended cardiac monitoring is uncertain among patients with stroke caused by small and large vessel disease. We conducted a meta‐analysis to estimate the yield of AF detection in this population.

Methods and Results

We searched PubMed, Cochrane, and SCOPUS databases for studies on AF detection in stroke patients and excluded studies restricted to patients with cryptogenic stroke or transient ischemic attack. We abstracted AF detection rates for 3 populations grouped by stroke etiology: large vessel stroke, small vessel stroke, and stroke of undefined etiology (a mixture of cryptogenic, small vessel, large vessel, and other stroke etiologies). Our search yielded 30 studies (n=5687). AF detection rates were similar in patients with large vessel (2.2%, 95% CI 0.3–5.5; n=830) and small vessel stroke (2.4%, 95% CI 0.4–6.1; n=520). No studies had a monitoring duration longer than 7 days. The yield of AF detection in the undefined stroke population was higher (9.2%; 95% CI 7.1–11.5) compared to small vessel stroke (P=0.02) and large vessel stroke (P=0.02) populations.

Conclusions

AF detection rate is similar in patients with small and large vessel strokes (2.2–2.4%). Because no studies reported on extended monitoring (>7 days) in these stroke populations, we could not estimate the yield of AF detection with long‐term cardiac monitoring. Randomized controlled trials are needed to examine the utility of AF detection with long‐term cardiac monitoring (>7 days) in this patient population.

Keywords: cardiac monitoring, Holter monitoring, large vessel stroke, cardiac embolism, atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular accident, ischemic stroke, lacunar stroke, cardiac emboli

Subject Categories: Atrial Fibrillation, Secondary Prevention, Ischemic Stroke, Anticoagulants, Cerebrovascular Disease/Stroke

Introduction

Screening for atrial fibrillation (AF) is of importance in patients who have suffered a stroke, because the detection of AF typically warrants a switch from antiplatelet therapy to anticoagulation for secondary stroke prevention.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Approximately 10% of patients with an ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) will have new AF detected during their hospital admission.6 However, AF can remain undetected during the acute hospitalization, and randomized controlled trials in cryptogenic stroke patients have shown increased rates of AF detection with long‐term ambulatory cardiac monitoring.7, 8 Most studies assessing long‐term cardiac monitoring after ischemic stroke are conducted in the subset of patients with cryptogenic stroke. In this population, the yield of AF detection is ≈10% per year.8 The prevalence of AF in patients with small or large vessel strokes is far less studied. We conducted a meta‐analysis to estimate the yield of AF detection in patients with stroke due to small and large vessel disease and in stroke patients in whom stroke etiology was not defined (a mixture of cryptogenic, small vessel, large vessel, and other stroke etiologies).

Methods

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

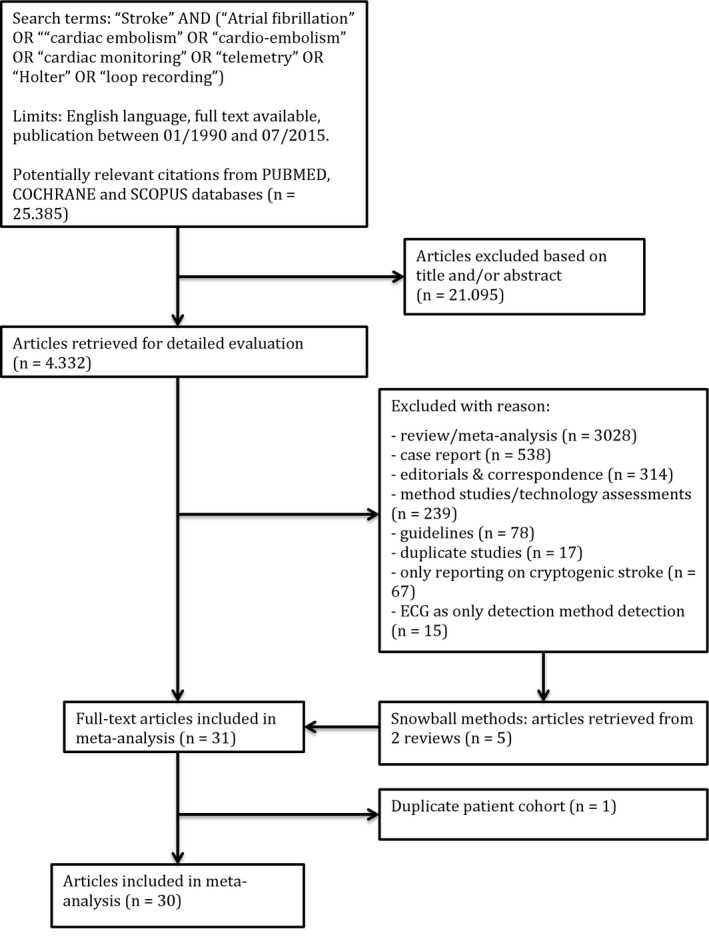

We followed PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses9 and searched PubMed, Cochrane, and SCOPUS databases for cardiac monitoring studies on detection of AF in stroke patients according to a prespecified protocol. We used the following search terms: “Stroke” AND any of “atrial fibrillation”, “cardiac embolism”, “cardio‐embolism”, “cardiac monitoring”, “telemetry”, “Holter”, “loop recording”. We searched articles from January 1990 until June 30, 2015. References of eligible clinical studies were examined to include any missed relevant articles. Search strategy and progress is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and progress.

We included studies with all types of long‐term cardiac monitoring and did not exclude studies based on monitoring duration, AF length definition, or interval between index event and initiation of monitoring. Studies were excluded if they were not in English, used standard 12‐lead (10 s) ECG as the only detection method, included patients with previously known AF, were limited to patients with TIA, or were limited to cryptogenic stroke patients.

For each included study, data were extracted by the first author. The study type (prospective versus retrospective and monocenter versus multicenter), study population, monitoring type, monitoring duration, and monitoring interval were recorded. In the studies that defined stroke etiology, the means of classification was recorded. If multiple, sequential AF detection methods were used, the total yield of all the individual methods was extracted. Since some studies reported rate of AF without specifying the yield per technique (standard ECG or long‐term monitoring), we performed a sensitivity analysis on studies that explicitly stated the yield of long‐term monitoring only. We adopted the definitions for AF that were used in the individual studies.

Studies were grouped according to whether or not a presumed stroke etiology was specified. We determined detection rates of AF in patients classified by stroke etiology: small vessel etiology, large vessel etiology, and undefined etiology (the latter included studies in which stroke etiology was not investigated or not reported on; these studies therefore include a mix of cryptogenic, small vessel, large vessel, and other stroke etiologies). This meta‐analysis was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42016033999). Approval by the institutional review committee and subject informed consent were waived.

Statistical Methods

Summary estimates of the percentage of patients with AF for each subgroup (small vessel disease, large vessel disease, and patients with undefined stroke etiology) were calculated using a random‐effects approach.10 Individual study estimates were the arcsine‐transformed proportions, to account for studies with zero events.11 Heterogeneity between studies was quantified by the I2 statistic and tested by Cochran's chi‐square test. A random‐effects meta‐regression was used to compare the percentages of AF detection between groups (small vessel stroke versus large vessel stroke versus undefined etiology). Meta‐regression was also used to explore to which extent study type, study population (stroke only versus stroke and TIA), and monitoring duration (more than versus less or equal to 24 hours) accounted for between‐study heterogeneity. The analysis was performed for each of these study characteristics separately, with group added as a fixed effect. Tukey adjustments were used for post‐hoc pairwise comparisons. All analyses were performed with SAS software (version 9.2 of the SAS System for Windows, Copyright © 2002 SAS Institute Inc), using the procedure PROC MIXED and self‐written code.

Results

The search yielded 25 385 results (Figure 1). The meta‐analysis included 30 studies6, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 comprising 5687 patients (study characteristics, Tables 1 and 2). All included studies were cohort studies. Twenty‐one studies had a prospective design1 and the other 10 were retrospective studies with consecutive enrollment of stroke patients.12, 13, 15, 23, 26, 31, 32, 33, 34, 38 Stroke etiology of included patients was not defined in 21 studies (4337 patients, Table 2).6, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 The 9 remaining studies categorized stroke patients according to stroke subtype (1350 patients with small or large vessel stroke, Table 1).12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Of those, 5 used the Trial of ORG 10172 in acute stroke treatment (TOAST) classification for allocation of stroke subtypes.12, 16, 17, 18, 20, 41 The other 4 used expert opinion (n=1) or did not specify the classification method (n=3).13, 14, 15, 19

Table 1.

Study Characteristics: Stroke Categorized According to Subtype

| Study | Study Type | Study Population | n | % AF | Monitoring Type | Interval Admission to Monitoring | Monitoring Duration: Where Given: Median (±SD) | AF Length Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bansil and Karim, 200412 | Retro, mono | (1) | 56 | 3.6 | Telemetry | N/S | 24 h | N/S |

| Shafqat et al, 200413 | Retro, mono | (2) | 42 | 0 | Holter monitoring | N/S | 22.8 h (±4) | N/S |

| Tagawa et al, 200714 | Pro, mono | (2) | 190 | 6.8 | Holter monitoring | ≤2 to 7 days | 24 h | Any |

| Lazzaro et al, 201215 | Retro, mono | (2) | 28 | 0 |

Telemetry Holter monitoring |

N/S |

73.4 h 29.8 h |

N/S |

| Shibazaki et al, 201216 | Pro, mono | (2) | 194 | 0 | Telemetry+Holter monitoring | N/S | 24 h | N/S |

| Grond et al, 201317 | Pro, multi | (2) | 564 | 2.5 | Holter monitoring | 24 | 73 h (range 1–134 days) | >30 s |

| Wohlfahrt et al, 201418 | Pro, mono | (2) | 106 | 17 | Holter monitoring | N/S | 160.8 h (IQR 105; 6–158 h) | >30 s |

| Maruyama et al, 201419 | Pro, mono | (2) | 148 | 2 | Holter monitoring | N/S | 24 h | N/S |

| Thakkar et al, 201420 | Pro, mono | (2) | 22 | 0 | Holter monitoring | <7 days | 24 h | N/S |

Symbols: %AF, proportion of patients in whom AF was detected; (1), ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack; (2), ischemic stroke. AF indicates atrial filbrillation; Mono, monocenter; multi, multicenter; n, number of patients in study; N/S, not specified; pro, prospective; retro, retrospective.

Table 2.

Study Characteristics: Stroke of Undefined Etiology

| Study | Study Type | Study Population | n | % AF | Type of Monitoring | Monitoring Interval | Monitoring Duration Where Given: Median (±SD) | AF Length Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schuchert et al, 199921 | Pro, mono | (2) | 82 | 6.1 | Holter monitoring | <21 days | 72 h | >1 minute |

| Jabaudon et al, 200422 | Pro, mono | (1)a | 139 | 8.6 | Holter monitoring+7 day event recorder | 26 h | 75 h | N/S |

| Vandenbroucke and Thijs, 200423 | Retro, mono | (1)b | 114 | 6.1 | Holter monitoring | N/S | 72 h (IQR 48–98) | N/S |

| Wallmann et al, 200724 | Pro, mono | (2)c | 127 | 14.2 | 3×7 day event recorder | N/S | 21 days | ≥30 s |

| Douen et al, 200825 | Pro, mono | (2) | 123 | 7.3 | Holter monitoring | 3.7 days | 24 h | N/S |

| Yu et al, 200926 | Retro, mono | (2) | 96 | 9.4 | Holter monitoring | N/S | 24 h | N/S |

| Vivanco Hidalgo et al, 200927 | Pro, mono | (2) | 465 | 7.1 | Telemetry | N/S | 55 h (36) | Any |

| Schaer et al, 200928 | Pro, mono | (2) | 147 | 0 | Holter monitoring | N/S | 24 h | >30 s |

| Stahrenberg et al, 201029 | Pro, mono | (2) | 220 | 12.7 | Holter monitoring | N/S | 7 days | >30 s |

| Kallmünzer et al, 201230 | Pro, mono | (2) | 245 | 7.3 | Serial ECG+Telemetry | N/S | 75.5 h (IQR 64–86) | N/S |

| Dogan et al, 201231 | Retro, mono | (2) | 400 | 10 | Holter monitoring | N/S | 24 h | >30 s |

| Sobocinski et al, 201232 | Retro, multi | (2) | 249 | 6.8 | Holter+intermittent ECG | <24 h | 22.6 h | N/S |

| Sposato et al, 201233 | Retro, mono | (2) | 110 | 18.2 | Telemetry | 0 h | 5 days (IQR 3–12) | Any |

| Atmuri et al, 201234 | Retro, mono | (2) | 129 | 9.3 | Holter monitoring | N/S | N/S | N/S |

| Rizos et al, 20126 | Pro, mono | (2) | 496 | 13.7 | Holter monitoring+Telemetry | 7.5 h (range 3.5–25) | 64 h (range 43–89.8) | >30 s |

| González Toledo et al, 201335 | Pro, mono | (2) | 211 | 10.9 | Telemetry | N/S | ≥72 h | N/S |

| Higgins et al, 201336 | Pro, multi | (2) | 100 | 25 | Holter (n=50)+Event recorder (n=50) | <7 days | 24 h | Any |

| Beaulieu‐Boire et al, 201337 | Pro, mono | (2) | 284 | 24 | Holter monitoring | <7 days | 24 h | N/S |

| Prefasi et al, 201338 | Retro, mono | (2)d | 147 | 2.7 | Telemetry+Holter | N/S | 96 h | Any |

| Fernandez et al, 201439 | Pro, mono | (2) | 149 | 12.8 | Event recorder | 0 h | 24 h | Any |

| Suissa et al, 201440 | Pro, mono | (2) | 304 | 13.8 | Telemetry+Holter | 0 h | 5.3 days (range 3.4–9.7) | >30 s |

Symbols: %AF, proportion of patients in whom AF was detected; (1), ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack; (2), ischemic stroke. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; IQR, interquartile range; mono, monocenter; multi, multicenter; n, number of patients in study; N/S, not specified; pro, prospective; retro, retrospective.

Only prior permanent AF excluded.

With confirmed diffusion‐weighted imaging lesion, prior AF documented 2 years prior to admission excluded.

AF during hospitalization or on 24‐h Holter excluded.

Patients over 50 years old excluded.

Median monitoring duration ranged from 22.6 hours32 to 504 hours24 (Tables 1 and 2). Median monitoring duration in cohorts reporting on patients classified according to stroke etiology (n=1350) was 24 hours (interquartile range: 24–73). In the 21 studies (n=4337) in which stroke etiology was not reported, the median monitoring duration was 55 hours (interquartile range: 24–75.5). Twelve studies reported an average monitoring duration of 24 hours or less.2 Only 2 studies monitored patients for at least 7 days.24, 29 None of these studies specified the stroke etiology. The interval between admission of a patient and the start of monitoring was not always specified and differed greatly between individual studies, ranging from initiation at admission33, 39, 40 to more than 2 to 3 weeks post stroke21 (Tables 1 and 2). The definition of AF differed between studies (Tables 1 and 2).

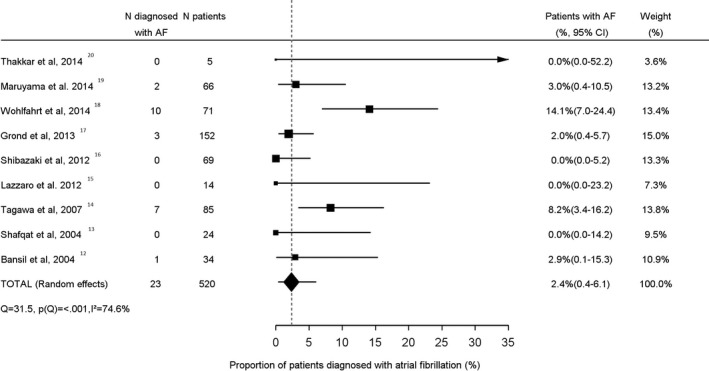

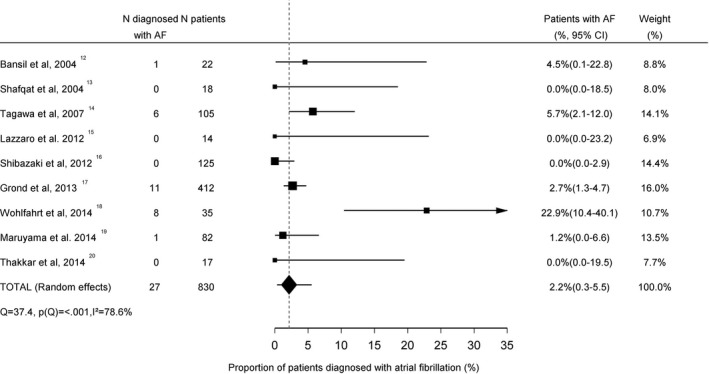

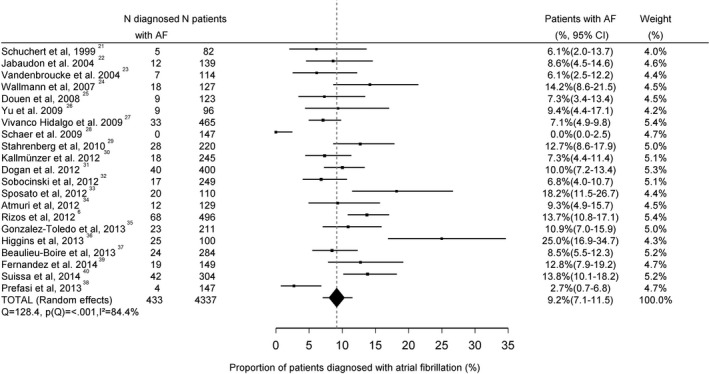

The mean AF detection yield was 2.4% (95% CI 0.4–6.1; Figure 2) in patients with small vessel stroke (n=520) and 2.2% (95% CI 0.3–5.5; Figure 3) in patients with large vessel disease (n=830; P for difference=0.99). The mean yield of AF detection in studies that did not define stroke etiology (n=4337) was 9.2% (95% CI 7.1–11.5; Figure 4). This was higher compared to patients with small vessel stroke (P=0.02) and patients with large vessel stroke (P=0.02).

Figure 2.

Proportion of small vessel stroke patients diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. AF indicates atrial fibrillation.

Figure 3.

Proportion of large vessel stroke patients diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. AF indicates atrial fibrillation.

Figure 4.

Proportion of stroke patients of undefined etiology diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. AF indicates atrial fibrillation.

Most studies either excluded patients with AF diagnosed on ECG or specified the number of patients who were diagnosed with AF based on ECG results. Six studies did not distinguish the proportion of patients diagnosed with AF on admission ECG.12, 19, 26, 27, 32, 35 We performed a sensitivity analysis after exclusion of those 6 studies to assess AF detection yield in the subgroup of studies reporting exclusively on long‐term cardiac monitoring. In this sensitivity analysis, the mean rate of AF detection was identical in patients with small vessel stroke (2.0%; 95% CI 0.0–7.5) and large vessel stroke (2.0%; 95% CI 0.0–7.9). In patients with undefined stroke etiology, the mean AF detection rate trended higher (9.3%; 95% CI 6.4–12.9), compared to patients with small vessel stroke (P=0.06) and large vessel stroke (P=0.08).

We identified considerable between‐study heterogeneity, with an I2 of 75% for studies reporting on small vessel stroke, an I2 of 79% for studies on large vessel stroke, and an I2 of 84% in undefined stroke studies. We therefore performed an exploratory analysis for factors accountable for this between‐study heterogeneity. Study type (prospective versus retrospective and monocenter versus multicenter) did not influence AF detection yield. Only 3.1% of heterogeneity was explained by the difference in detection rates between prospective and retrospective studies (P=0.24) and 1.5% by the difference in yield between monocenter and multicenter studies (P=0.45). Monitoring type (Holter monitoring versus other) explained only 2.8% of the heterogeneity (P=0.33). Monitoring duration, dichotomized in less or more than 24 hours, accounted for 7.3% of the between‐study heterogeneity with a trend toward higher rates with longer monitoring duration (3.2% versus 5.5%; P=0.16). AF length definition (undefined or shorter than 30 s versus longer or equal to 30 s) explained 5.1% of the heterogeneity between studies with a nonsignificant trend towards higher detection yield in studies defining AF for a duration of at least 30 s (3.5% versus 6.1%, P=0.13). Inclusion of TIA patients in the study population explained 29.4% of the between‐study heterogeneity. The mean AF detection rate in studies including stroke patients was 1.6% compared to 5.2% in studies including stroke and TIA patients (P=0.01). Correction for inclusion of TIA patients in the study population did not alter the result that the AF detection rate is higher in patients with undefined stroke etiology compared to patients with small vessel stroke (P=0.004) and large vessel stroke (P=0.002).

Discussion

This meta‐analysis demonstrates that the yield of AF detection with relatively short duration ambulatory cardiac monitoring is ≈2% to 2.5% in patients with small and large vessel disease strokes. In studies that did not define stroke etiology (a mixture of cryptogenic, small vessel, large vessel, and other stroke etiologies), the rate of AF detection was 9.3%, which is similar to previously documented rates of AF detection in cryptogenic stroke patients.7, 8

Many observational studies and 2 randomized trials have been published on long‐term cardiac monitoring of cryptogenic stroke patients with monitoring duration of 30 days and more.7, 8 The results show a relationship between monitoring duration and the rate of AF identification. This relationship was most strikingly demonstrated in the Cryptogenic stroke and underlying AF (CRYSTAL AF) trial, in which a subgroup of patients underwent continuous cardiac monitoring for a period of 3 years.8 Based on the findings on cardiac monitoring in cryptogenic stroke patients, long‐term monitoring is recommended for patients with stroke of unknown etiology. In our meta‐analysis of patients with stroke due to large or small vessel disease, the median duration of monitoring was only 24 hours and we did not identify any studies that reported on extended monitoring (>7 days) in this population. Due to this lack of data, no recommendation can be made on cardiac monitoring duration in this subgroup of patients.

The etiologic and therapeutic implications of AF detection in patients with large or small vessel disease stroke are not firmly established. Especially in patients with large vessel disease as a potential cause of the ischemic stroke, qualifying AF as incidental versus pathological can be rather complicated. Although in some patients the detection of AF leads to a change in the presumed stroke etiology, in many others AF detection could be considered incidental and would therefore not lead to a change in the etiological classification. Furthermore, while all guidelines recommend anticoagulation over antiplatelet therapy in patients with AF and a history of stroke, the benefit of anticoagulation has never been directly demonstrated in patients with presumed small or large vessel disease stroke and a coinciding finding of paroxysmal AF on long‐term ambulatory cardiac monitoring. It is possible that the relative benefit of anticoagulation is reduced in this population and could differ between patients with small versus large vessel disease. It is also possible that the baseline risk of recurrent stroke is lower in this population than would be expected based on the patients’ risk scores (CHADS2 or CHA2DS2–VASc). This would translate into a decrease of the absolute benefit of anticoagulation even if the relative benefit were the same.

This study has several limitations. First, although this is the largest study of AF detection in patients with large and small vessel disease strokes, we could still have lacked power to detect a significant difference in AF detection rates between patients with small and large vessel disease strokes. Second, considerable heterogeneity between individual studies was revealed. An exploratory analysis failed to detect important variables explaining the heterogeneity in AF detection rates. “Study population” defined as inclusion/exclusion of TIA patients was the only significant factor in the meta‐regression, explaining 29% of the between‐study heterogeneity. However, the higher detection yield upon inclusion of TIA patients is unintuitive, and the difference in study population did not explain the obtained differences in AF detection yield between studies where stroke etiology was undefined compared to studies limited to large or small vessel stroke patients. Other variables that were either not assessed in the study populations or were too variable among studies to be included in the analysis (eg, type of monitoring device) may account for some of the unexplained heterogeneity. Third, since monitoring duration in most studies was relatively short, no suggestion on optimal monitoring duration can be derived from these data. For that reason, we were also not able to calculate the cost‐effectiveness of long‐term cardiac monitoring in patients with small or large vessel stroke.

In summary, the AF detection rate with long‐term cardiac monitoring among patients with small and large vessel disease stroke is 2% to 2.5%. However, these data are based on only 9 studies, none of which used monitoring durations that exceeded 7 days. Compared to cryptogenic stroke populations, data on long‐term cardiac monitoring are therefore very limited in patients with small and large vessel strokes and clinical trials are needed to determine the yield of AF detection with long‐term monitoring in this population. These trials may also give some insight into the rate of stroke recurrence, the effect of anticoagulation on stroke recurrence among patients with presumed small or large vessel disease stroke who are diagnosed with AF, and the cost‐effectiveness of long‐term cardiac monitoring in this specific population.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Lemmens is a senior clinical investigator of FWO Flanders.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e004151 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004151)

Presented as an abstract at the European Stroke Organisation Conference, May 10, 2016 in Barcelona, Spain.

Notes

References

- 1. Keogh C, Wallace E, Dillon C, Dimitrov BD, Fahey T. Validation of the CHADS2 clinical prediction rule to predict ischaemic stroke. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:528–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boriani G, Botto GL, Padeletti L, Santini M, Capucci A, Gulizia M, Ricci R, Biffi M, De Santo T, Corbucci G, Lip GY. Improving stroke risk stratification using the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2‐VASc risk scores in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation by continuous arrhythmia burden monitoring. Stroke. 2011;42:1768–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, Conti JB, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Murray KT, Sacco RL, Stevenson WG, Tchou PJ, Tracy CM, Yancy CW. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130:2071–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar M. Meta‐analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman EB, Deenayalu N, Ezekowitz MD, Camm AJ, Weitz JI, Lewis BS, Parkhomenko A, Yamashita T, Antman EM. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta‐analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383:955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rizos T, Guntner J, Jenetzky E, Marquardt L, Reichardt C, Becker R, Reinhardt R, Hepp T, Kirchhof P, Aleynichenko E, Ringleb P, Hacke W, Veltkamp R. Continuous stroke unit electrocardiographic monitoring versus 24‐hour Holter electrocardiography for detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:2689–2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gladstone DJ, Spring M, Dorian P, Panzov V, Thorpe KE, Hall J, Vaid H, O'Donnell M, Laupacis A, Côté R, Sharma M, Blakely JA, Shuaib A, Hachinski V, Coutts SB, Sahlas DJ, Teal P, Yip S, Spence DJ, Buck B, Verreault S, Casaubon LK, Penn A, Selchen D, Jin A, Howse D, Mehdiratta M, Boyle K, Aviv R, Kapral MK, Mamdani M; EMBRACE Investigators and Coordinators . Atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2467–2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanna T, Diener HC, Passman RS, Di Lazzaro V, Bernstein RA, Morillo CA, Rymer MM, Thijs V, Rogers T, Beckers F, Lindborg K, Brachmann J. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2478–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter J. Arcsine test for publication bias in meta‐analysis with binary outcomes. Stat Med. 2008;27:746–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bansil S, Karim H. Detection of atrial fibrillation in patients with acute stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;13:12–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shafqat S, Kelly PJ, Furie KL. Holter monitoring in the diagnosis of stroke mechanism. Intern Med J. 2004;34:305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tagawa M, Takeuchi S, Chinushi M, Saeki M, Taniguchi Y, Nakamura Y, Ohno H, Kitazawa K, Aizawa Y. Evaluating patients with acute ischemic stroke with special reference to newly developed atrial fibrillation in cerebral embolism. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30:1121–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lazzaro A, Krishnan K, Prabhakaran S. Detection of atrial fibrillation with concurrent Holter monitoring and continuous cardiac telemetry following ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shibazaki K, Kimura K, Fujii S, Sakai K, Iguchi Y. Brain natriuretic peptide levels as a predictor for new atrial fibrillation during hospitalization in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1303–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grond M, Jauss M, Hamann G, Stark E, Veltkamp R, Nabavi D, Horn M, Weimar C, Köhrmann M, Wachter R, Rosin L, Kirchhof P. Improved detection of silent atrial fibrillation using 72‐hour Holter ECG in patients with ischemic stroke: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Stroke. 2013;44:3357–3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wohlfahrt J, Stahrenberg R, Weber‐Krüger M, Gröschel S, Wasser K, Edelmann F, Seegers J, Wachter R, Gröschel K. Clinical predictors to identify paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maruyama K, Shiga T, Iijima M, Moriya S, Mizuno S, Toi S, Arai K, Ashihara K, Abe K, Uchiyama S. Brain natriuretic peptide in acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:967–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thakkar S, Bagarhatta R. Detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or flutter in patients with acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack by Holter monitoring. Indian Heart J. 2014;66:188–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schuchert A, Behrens G, Meinertz T. Impact of long‐term ECG recording on the detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients after an acute ischemic stroke. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1999;22:1082–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jabaudon D, Sztajzel J, Sievert K, Landis T, Sztajzel R. Usefulness of ambulatory 7‐day ECG monitoring for the detection of atrial fibrillation and flutter after acute stroke and transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2004;35:1647–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vandenbroucke E, Thijs VN. Diagnostic and therapeutic impact of ambulatory electrocardiography in acute stroke. Acta Neurol Belg. 2004;104:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wallmann D, Tüller D, Wustmann K, Meier P, Isenegger J, Arnold M, Mattle HP, Delacrétaz E. Frequent atrial premature beats predict paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in stroke patients. An opportunity for a new diagnostic strategy. Stroke. 2007;38:2292–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Douen AG, Pageau N, Medic S. Serial electrocardiographic assessments significantly improve detection of atrial fibrillation 2.6 fold in patients with acute stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:480–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu EH, Lungu C, Kanner RM, Libman RB. The use of diagnostic tests in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18:178–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vivanco Hidalgo RM, Rodríguez Campello A, Ois Santiago A, Cuadrado Godia E, Pont Sunyer C, Roquer J. Cardiac monitoring in stroke units: importance of diagnosing atrial fibrillation in acute ischemic stroke. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2009;62:564–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schaer B, Sticherling C, Lyrer P, Osswald S. Cardiological diagnostic work‐up in stroke patients—a comprehensive study of test results and therapeutic implications. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stahrenberg R, Weber‐Krüger M, Seegers J, Edelmann F, Lahno R, Haase B, Mende M, Wohlfahrt J, Kermer P, Vollmann D, Hasenfuss G, Gröschel K, Wachter R. Enhanced detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation by early and prolonged continuous Holter monitoring in patients with cerebral ischemia presenting in sinus rhythm. Stroke. 2010;41:2884–2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kallmünzer B, Breuer L, Hering C, Raaz‐Schrauder D, Kollmar R, Huttner HB, Schwab S, Köhrmann M. A structured reading algorithm improves telemetric detection of atrial fibrillation after acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:994–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dogan U, Dogan EA, Tekinalp M, Tokgoz OS, Aribas A, Ozdemir K, Gok H, Yuruten B. P‐wave dispersion for predicting paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in acute ischemic stroke. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9:108–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sobocinski PD, Rooth EA, Kull VF, von Arbin M, Wallen H, Rosenqvist M. Improved screening for silent atrial fibrillation after ischaemic stroke. Europace. 2012;14:1112–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sposato LA, Klein FR, Jauregui A, Ferrua M, Klin P, Zamora R, Riccio PM, Rabinstein A. Newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation after acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack: importance of immediate and prolonged continuous cardiac monitoring. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21:210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Atmuri K, Hughes A, Coles D, Ahmad O, Neeman T, Lueck C. The role of cardiac disease parameters in predicting the results of Holter monitoring in patients with acute ischaemic stroke. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19:965–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gonzalez Toledo ME, Klein FR, Riccio PM, Cassara FP, Muñoz Giacomelli FM, Racosta JM, Roberts ES, Sposato LA. Atrial fibrillation detected after acute ischemic stroke: evidence supporting the neurogenic hypothesis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:486–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Higgins P, MacFarlane PW, Dawson J, McInnes GT, Langhorne P, Lees KR. Noninvasive cardiac event monitoring to detect atrial fibrillation after ischemic stroke: a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2525–2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beaulieu‐Boire I, Leblanc N, Berger L, Boulanger JM. Troponin elevation predicts atrial fibrillation in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:978–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Prefasi D, Martínez‐Sánchez P, Rodriguez‐Sanz A, Fuentes B, Filgueiras‐Rama D, Ruiz‐Ares G, Sanz‐Cuesta BE, Díez‐Tejedor E. Atrial fibrillation in young stroke patients: do we underestimate its prevalence? Eur J Neurol. 2013;20:1367–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fernandez V, Béjot Y, Zeller M, Hamblin J, Daubail B, Jacquin A, Maza M, Touzery C, Cottin Y, Giroud M. Silent atrial fibrillation after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: interest of continuous ECG monitoring. Eur Neurol. 2014;71:313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Suissa L, Lachaud S, Mahagne M‐H. Continuous ECG monitoring for tracking down atrial fibrillation after stroke: Holter or automated analysis strategy? Eur Neurol. 2014;72:7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Adams HP, Bendixen BH, Kapelle J, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, Marsh EE. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]